Submitted:

04 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

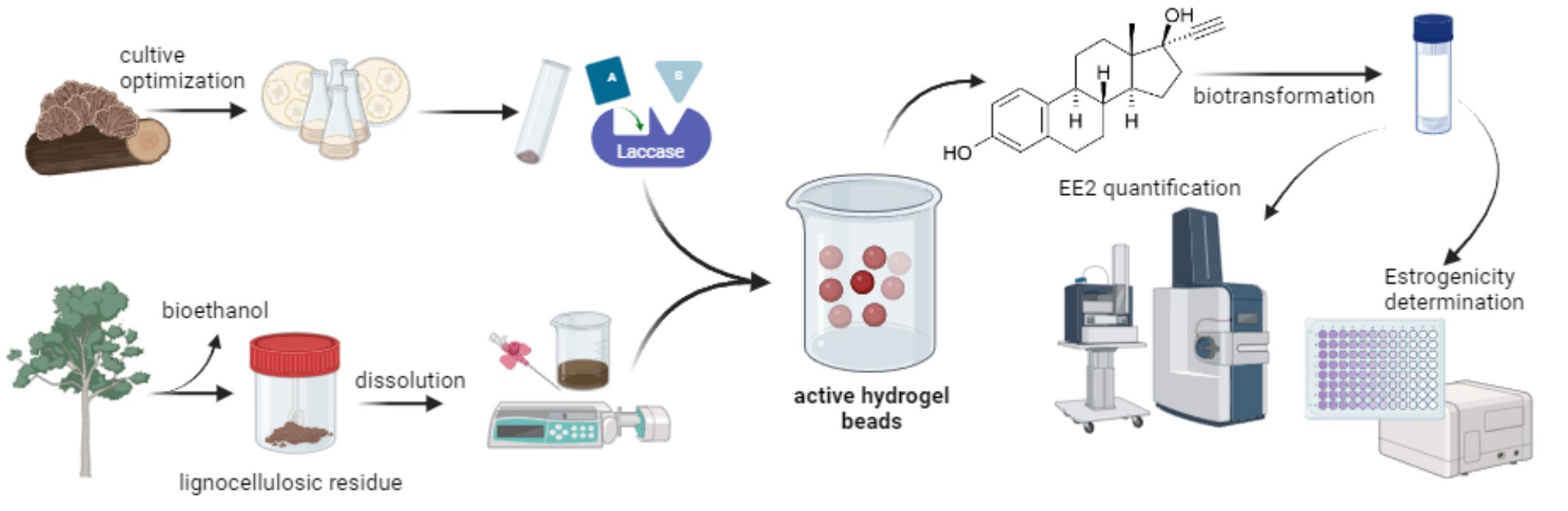

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

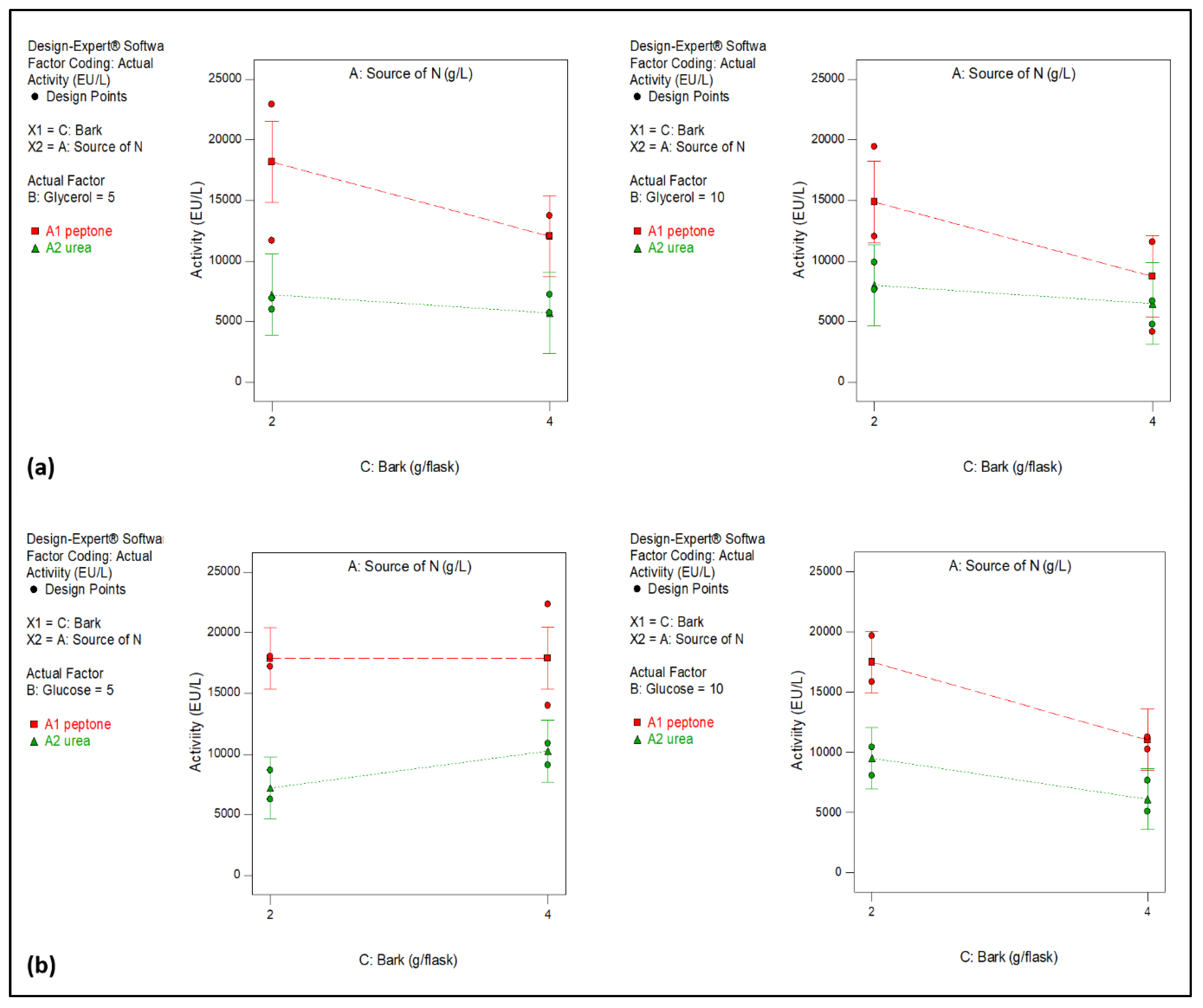

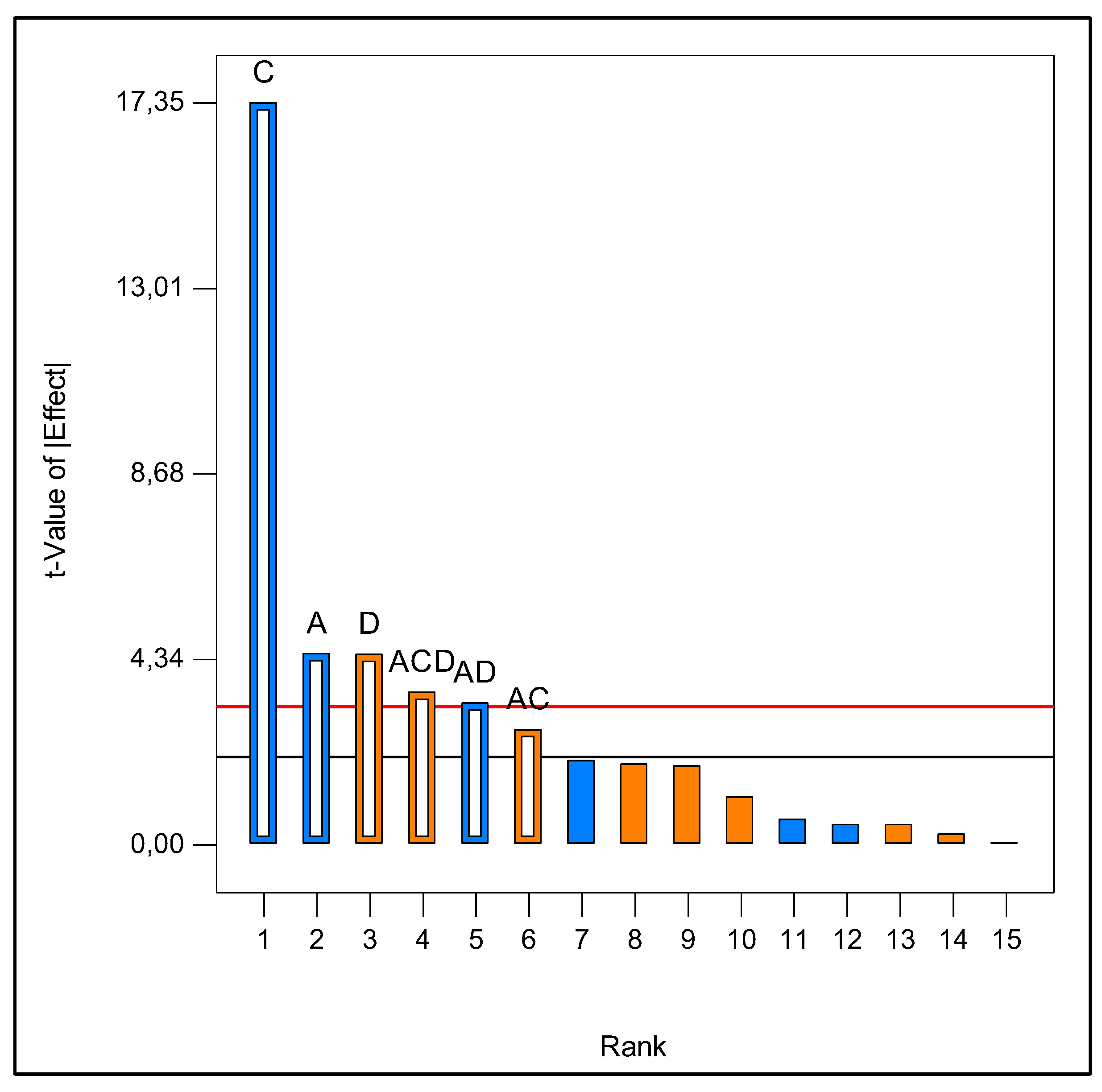

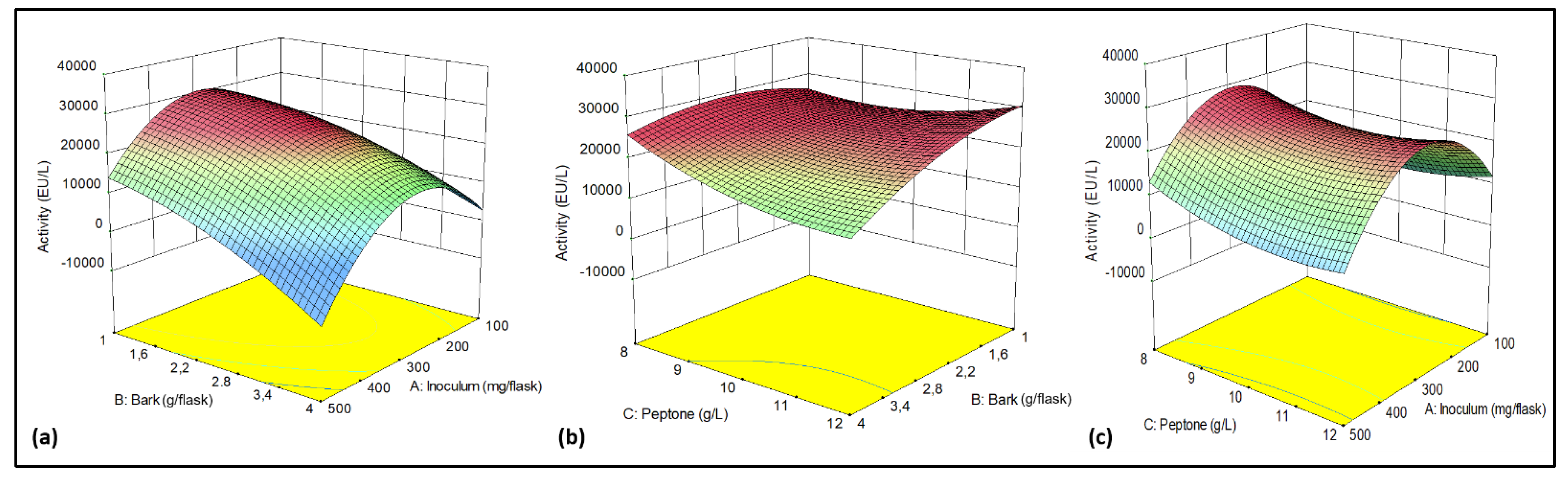

2.1. Optimization of Culture Medium for Laccase Production

| Sample | EC50 (µg/L) | Relative Potency |

|---|---|---|

| E2 | 0.047 ± 0.02 | |

| EE2 | 0.028 ± 0.02 | 1,68 |

| EE2 + soluble laccase (R-SLac 0.5) | 0.391 ± 0.33 | 1,20 x 10 – 1 |

| EE2 + hydrogel beads (B-EE2) | 0.598 ± 0.13 | 7,90 x 10 – 2 |

| EE2 + active hydrogel beads (R-ILac) | 4.819 ± 0.22 | 9,75 x 10 – 3 |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Laccase Activity Assay

3.3. Protein Determination

3.4. Laccase Production

3.5. Optimisation of Culture Medium for Laccase Production

3.5.1. Multilevel Categoric Model

3.5.2. Full 24 Factorial Design

3.5.3. Central Composite Design

3.6. Active Hydrogel Formation

3.7. Estrogen Biodegradation

3.8. Yeast Estrogen Screen (YES) Bioassay

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hejna, M.; Kapuścińska, D.; Aksmann, A. Pharmaceuticals in the Aquatic Environment: A Review on Eco-Toxicology and the Remediation Potential of Algae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J. Pollution from Drug Manufacturing: Review and Perspectives. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moukhtari, F. El; Martín-Pozo, L.; Zafra-Gómez, A. Strategies Based on the Use of Microorganisms for the Elimination of Pollutants with Endocrine-Disrupting Activity in the Environment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, K.A.; Blanchfield, P.J.; Mills, K.H.; Palace, V.P.; Evans, R.E.; Lazorchak, J.M.; Flick, R.W. Collapse of a Fish Population after Exposure to a Synthetic Estrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 8897–8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) Overview of Endocrine Disruption. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/endocrine-disruption/overview-endocrine-disruption (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Johnson, A.C.; Dumont, E.; Williams, R.J.; Oldenkamp, R.; Cisowska, I.; Sumpter, J.P. Do Concentrations of Ethinylestradiol, Estradiol, and Diclofenac in European Rivers Exceed Proposed EU Environmental Quality Standards? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 12297–12304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdan, M.M.S.; Kumar, R.; Leung, S.W. The Environmental and Health Impacts of Steroids and Hormones in Wastewater Effluent, as Well as Existing Removal Technologies: A Review. Ecologies 2022, 3, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Fan, G.; Yu, W.; Yang, S.; Zhou, J.; Luo, J. Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Steroid Estrogens in Environmental Water Samples: A Five-Year Worldwide Perspective. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haakenstad, A.; Angelino, O.; S Irvine, C.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Bienhoff, K.; Bintz, C.; Causey, K.; Ashworth Dirac, M.; Fullman, N.; Gakidou, E.; et al. Measuring Contraceptive Method Mix, Prevalence, and Demand Satisfied by Age and Marital Status in 204 Countries and Territories, 1970-2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. www.thelancet.com 2022, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffero, L.; Alcántara-Durán, J.; Alonso, C.; Rodríguez-Gallego, L.; Moreno-González, D.; García-Reyes, J.F.; Molina-Díaz, A.; Pérez-Parada, A. Basin-Scale Monitoring and Risk Assessment of Emerging Contaminants in South American Atlantic Coastal Lagoons. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697, 134058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.B.; Maillard, J.Y.; Simões, L.C.; Simões, M. Emerging Contaminants Affect the Microbiome of Water Systems—Strategies for Their Mitigation. npj Clean Water 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzionek, A.; Wojcieszyńska, D.; Guzik, U. Natural Carriers in Bioremediation: A Review. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 23, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.M.; Dahiya, P. Enzyme-Based Biodegradation of Toxic Environmental Pollutants. Dev. Wastewater Treat. Res. Process. Microb. Degrad. Xenobiotics through Bact. Fungal Approach 2022, 311–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdarta, J.; Nguyen, L.N.; Jankowska, K.; Jesionowski, T.; Nghiem, L.D. A Contemporary Review of Enzymatic Applications in the Remediation of Emerging Estrogenic Compounds. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 0, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macellaro, G.; Pezzella, C.; Cicatiello, P.; Sannia, G.; Piscitelli, A. Fungal Laccases Degradation of Endocrine Disrupting Compounds. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 614038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, L.; Eibes, G.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G.; Lema, J.M. Removal of Estrogenic Compounds from Filtered Secondary Wastewater Effluent in a Continuous Enzymatic Membrane Reactor. Identification of Biotransformation Products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 4536–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Persistence and Impact of Steroidal Estrogens on the Environment and Their Laccase-Assisted Removal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daronch, N.A.; Kelbert, M.; Pereira, C.S.; de Araújo, P.H.H.; de Oliveira, D. Elucidating the Choice for a Precise Matrix for Laccase Immobilization: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 397, 125506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbent, M.P.; Magario, I.; Saux, C. Immobilizing White-Rot Fungi Laccase: Toward Bio-Derived Supports as a Circular Economy Approach in Organochlorine Removal. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mate, D.M.; Alcalde, M. Laccase: A Multi-Purpose Biocatalyst at the Forefront of Biotechnology. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnari, T.; Braga, D.M.; dos Santos, C.S.A.; Torres, B.H.C.; Modkovski, T.A.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Maciel, G.M. Laccases as Green and Versatile Biocatalysts: From Lab to Enzyme Market—an Overview. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusz, G.; Skwarek, E.; Pawlik, A. Potential of Laccase as a Tool for Biodegradation of Wastewater Micropollutants. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Singh, A.; Varma, A.; Porwal, S. Recent Advancements in Biotechnological Applications of Laccase as a Multifunctional Enzyme. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 16, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zofair, S.F.F.; Ahmad, S.; Hashmi, M.A.; Khan, S.H.; Khan, M.A.; Younus, H. Catalytic Roles, Immobilization and Management of Recalcitrant Environmental Pollutants by Laccases: Significance in Sustainable Green Chemistry. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 309, 114676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Cheng, J.; Li, K.; Zhang, S.; Dong, X.; Paizullakhanov, M.S.; Chen, D. Preparation and Application of Laccase-Immobilized Magnetic Biochar for Effective Degradation of Endocrine Disruptors: Efficiency and Mechanistic Analysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybarczyk, A.; Smułek, W.; Ejsmont, A.; Goscianska, J.; Jesionowski, T.; Zdarta, J. The Role of Metal–Organic Framework (MOF) in Laccase Immobilization for Advanced Biocatalyst Formation for Use in Micropollutants Removal. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 371, 125954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, V.; Giorgi, V.; Bonfiglio, F.; Menéndez, P.; Gioia, L.; Ovsejevi, K. Lignocellulosic Residues from Bioethanol Production: A Novel Source of Biopolymers for Laccase Immobilization. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13463–13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanov, I.; Raud, M.; Kikas, T. The Role of Ionic Liquids in the Lignin Separation from Lignocellulosic Biomass. Energies 2020, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Meyer, L.E.; Kara, S. Enzyme Immobilization in Hydrogels: A Perfect Liaison for Efficient and Sustainable Biocatalysis. Eng. Life Sci. 2022, 22, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, H.T.; Marr, P.C.; Marr, A.C. Enzyme Entrapment, Biocatalyst Immobilization without Covalent Attachment. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 4980–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; An, S.; Won, K.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.H. Entrapment of Enzymes into Cellulose-Biopolymer Composite Hydrogel Beads Using Biocompatible Ionic Liquid. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2012, 75, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botto, E.; D’annibale, A.; Petruccioli, M.; Galetta, A.; Martínez, S.; Bettucci, L.; Menéndez, P. Ligninolytic Enzymes Production by Dichostereum Sordulentum Cultures in the Presence of Eucalyptus Bark as a Natural Laccase Stimulator. J. Adv. Biotechnol. 2015, 5, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourkhanali, K.; Khayati, G.; Mizani, F.; Raouf, F. Isolation, Identification and Optimization of Enhanced Production of Laccase from Galactomyces Geotrichum under Solid-State Fermentation. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.J.; Jiao, J.; Gai, Q.Y.; Fu, J.X.; Fu, Y.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Gao, J. Bioprocessing of Pigeon Pea Roots by a Novel Endophytic Fungus Penicillium Rubens for the Improvement of Genistein Yield Using Semi-Solid-State Fermentation with Water. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 90, 103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments; 8th ed.; John Wiley: New York, 2012.

- Hadiyat, M.A.; Sopha, B.M.; Wibowo, B.S. Response Surface Methodology Using Observational Data: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección General Forestal MGAP Superficie Forestal Del Uruguay 2022 (Bosques Plantados); Montevideo, Uruguay, 2022;

- Gioia, L.; Manta, C.; Ovsejevi, K.; Burgueño, J.; Menéndez, P.; Rodriguez-Couto, S. Enhancing Laccase Production by a Newly-Isolated Strain of Pycnoporus Sanguineus with High Potential for Dye Decolouration. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 34096–34103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Jana, A.K. Production of Laccase by Repeated Batch Semi-Solid Fermentation Using Wheat Straw as Substrate and Support for Fungal Growth. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripollés, C.; Ibáñez, M.; Sancho, J. V.; López, F.J.; Hernández, F. Determination of 17β-Estradiol and 17α-Ethinylestradiol in Water at Sub-Ppt Levels by Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 5028–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turull, M.; Buttiglieri, G.; Vazquez, V.; Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Santos, L.H.M.L.M. Analytical Upgrade of a Methodology Based on UHPLC-MS/MS for the Analysis of Endocrine Disrupting Compounds in Greywater. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics 2023, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, L.; Onder, A.; Sarker, S.D. A Review on the Recent Advances in HPLC, UHPLC and UPLC Analyses of Naturally Occurring Cannabinoids (2010–2019). Phytochem. Anal. 2020, 31, 413–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auriol, M.; Filali-Meknassi, Y.; Tyagi, R.D.; Adams, C.D. Laccase-Catalyzed Conversion of Natural and Synthetic Hormones from a Municipal Wastewater. Water Res. 2007, 41, 3281–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamidipati, S.; Ahmed, A. A First Report on Competitive Inhibition of Laccase Enzyme by Lignin Degradation Intermediates. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 2020, 65, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I.C.; Bruhn, R.; Gandrass, J. Analysis of Estrogenic Activity in Coastal Surface Waters of the Baltic Sea Using the Yeast Estrogen Screen. Chemosphere 2006, 63, 1870–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdarta, J.; Jankowska, K.; Strybel, U.; Marczak, Ł.; Nguyen, L.N.; Oleskowicz-Popiel, P.; Jesionowski, T. Bioremoval of Estrogens by Laccase Immobilized onto Polyacrylonitrile/Polyethersulfone Material: Effect of Inhibitors and Mediators, Process Characterization and Catalytic Pathways Determination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Krohn, R.I.; Hermanson, G.T.; Mallia, A.K.; Gartner, F.H.; Provenzano, M.D.; Fujimoto, E.K.; Goeke, N.M.; Olson, B.J.; Klenk, D.C. Measurement of Protein Using Bicinchoninic Acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985, 150, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, S.; Nakasone, K.K. New Records of Interesting Corticioid Basidiomycota from Uruguay. Check List 2014, 10, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, E.J.; Sumpter, J.P. Estrogenic Activity of Surfactants and Some of Their Degradation Products Assessed Using a Recombinant Yeast Screen. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1996, 15, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F Value | p- value Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 3.339E+008 | 6 | 5.566E+007 | 9.17 | 0.0021 |

| A-Source of N | 2.433E+008 | 1 | 2.433E+008 | 40.07 | 0.0001 |

| B-Glucose | 2.085E+007 | 1 | 2.085E+007 | 3.43 | 0.0969 |

| C-Bark | 1.150E+007 | 1 | 1.150E+007 | 1.89 | 0.2020 |

| AB | 7.373E+006 | 1 | 7.373E+006 | 1.21 | 0.2991 |

| AC | 9.213E+006 | 1 | 9.213E+006 | 1.52 | 0.2492 |

| BC | 4.172E+007 | 1 | 4.172E+007 | 6.87 | 0.0277 |

| Residual | 5.464E+007 | 9 | 6.071E+006 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 1.141E+006 | 1 | 1.141E+006 | 0.17 | 0.6904 |

| Pure Error | 5.350E+007 | 8 | 6.688E+006 | ||

| Cor Total | 3.886E+008 | 15 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F Value | p- value Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 2.768E+008 | 5 | 5.535E+007 | 4.07 | 0.0283 |

| A-Source of N | 1.739E+008 | 1 | 1.739E+008 | 12.78 | 0.0051 |

| B-Glycerol | 6.395E+006 | 1 | 6.395E+006 | 0.47 | 0.5087 |

| C-Bark | 5.839E+007 | 1 | 5.839E+007 | 4.29 | 0.0652 |

| AB | 1.666E+007 | 1 | 1.666E+007 | 1.22 | 0.2945 |

| AC | 2.143E+007 | 1 | 2.143E+007 | 1.57 | 0.2382 |

| Residual | 1.361E+008 | 10 | 1.361E+007 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 1.066E+007 | 2 | 5.328E+006 | 0.34 | 0.7218 |

| Pure Error | 1.255E+008 | 8 | 1.568E+007 | ||

| Cor Total | 4.129E+008 | 15 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F Value | p- value Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1.769E+009 | 6 | 2.948E+008 | 58.68 | < 0.0001 |

| A-Inoculum | 1.004E+008 | 1 | 1.004E+008 | 19.97 | 0.0001 |

| C-Bark | 1.513E+009 | 1 | 1.513E+009 | 301.04 | < 0.0001 |

| D-Peptone | 9.977E+007 | 1 | 9.977E+007 | 19.86 | 0.0002 |

| AC | 3.649E+007 | 1 | 3.649E+007 | 7.26 | 0.0124 |

| AD | 5.522E+007 | 1 | 5.522E+007 | 10.99 | 0.0028 |

| ACD | 6.394E+007 | 1 | 6.394E+007 | 12.73 | 0.0015 |

| Curvature | 1.057E+009 | 1 | 1.057E+009 | 210.28 | < 0.0001 |

| Residual | 1.256E+008 | 25 | 5.024E+006 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 6.914E+007 | 9 | 7.682E+006 | 2.18 | 0.0837 |

| Pure Error | 5.647E+007 | 16 | 3.529E+006 | ||

| Cor Total | 2.951E+009 | 32 |

| Source | Squares | df | Square | Value | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 8.302E+008 | 9 | 9.224E+007 | 49.49 | 0.0002 |

| A-Inoculum | 6.184E+006 | 1 | 6.184E+006 | 3.32 | 0.1282 |

| B-Bark | 8.426E+007 | 1 | 8.426E+007 | 45.20 | 0.0011 |

| C-Peptone | 1.538E+007 | 1 | 1.538E+007 | 8.25 | 0.0349 |

| AB | 3.291E+007 | 1 | 3.291E+007 | 17.66 | 0.0085 |

| AC | 1.107E+007 | 1 | 1.107E+007 | 5.94 | 0.0589 |

| BC | 7.258E+007 | 1 | 7.258E+007 | 38.94 | 0.0015 |

| A2 | 2.574E+007 | 1 | 2.574E+007 | 13.81 | 0.0138 |

| B2 | 1.661E+006 | 1 | 1.661E+006 | 0.89 | 0.3885 |

| C2 | 1.081E+006 | 1 | 1.081E+006 | 0.58 | 0.4806 |

| Residual | 9.320E+006 | 5 | 1.864E+006 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 7.317E+006 | 2 | 3.659E+006 | 5.48 | 0.0996 |

| Pure Error | 2.003E+006 | 3 | 6.675E+005 | ||

| Cor Total | 8.395E+008 | 14 |

| Sample | EE2 recovered (%) |

|---|---|

| EE2 | 102.6 ± 7.1 |

| R-SLac 0.1 | 27.2 ± 2.1 |

| R-SLac 0.3 | 9.6 ± 1.0 |

| R-SLac 0.5 | 7.1 ± 1.5 |

| R-ILac | 1.2 ± 0.5 |

| B-EE2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| B-ILac | <LOD |

| SLac | <LOD |

| R-ILac W | 10.6 ± 5.7 |

| B-ILac W | <LOD |

| B-EE2 W | 20.2 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).