# These two authors share the first co-authorship

1. Introduction

Oral administration is the most convenient and patient-friendly route for treating both systemic and local gastrointestinal diseases. However, despite its advantages over injections, it remains challenging due to the complex physiological, biochemical, and anatomical barriers of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract After ingestion, a drug must withstand the acidic pH and proteolytic enzymes (e.g., pepsin, cathepsin) in the stomach, followed by the enzymatic degradation in the small intestine. Carbohydrates such as oligosaccharides and maltose are hydrolyzed into glucose, fructose, galactose, and mannose by sucrase, maltase, and lactase; lipids are broken down into glycerol and fatty acids by pancreatic triacylglycerol lipase and carboxyl ester lipase; and peptides are digested into amino acids by trypsin, chymotrypsin, carboxypeptidase, dipeptidase, and aminopeptidase. To exert its therapeutic effect, the drug must then be absorbed through intestinal enterocytes into systemic circulation. Many drugs exhibit poor bioavailability via this route, mainly due to degradation and limited permeability. To address this, enteric coatings are often applied to protect the active ingredient in acidic conditions and allow its release in the more alkaline environment of the small intestine. Despite such strategies, achieving effective and consistent oral delivery remains a major pharmaceutical challenge [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Mucoadhesive systems have attracted considerable attention due to their ability to adhere to mucosal surfaces, ensuring prolonged contact with the absorption site. In oral drug delivery, these systems enhance residence time within the GI tract and enable controlled, sustained drug release. Mucoadhesive polymeric carriers can be tailored to target specific regions of the GI tract, such as the stomach, small intestine, or colon, thereby improving local absorption and therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, administration via the oral mucosa can bypass hepatic first-pass metabolism and enzymatic degradation, enhancing bioavailability and accelerating drug onset. The advantages of mucoadhesive systems include prolonged contact with the target site without interfering with physiological functions, improved bioavailability, reduced dosing frequency, simplified administration, and the potential for localized or site-specific therapy [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Hydrophilic macromolecules containing hydroxyl, carboxyl, or amine groups are the most commonly used polymers for mucoadhesive applications due to their ability to form hydrogen bonds with mucin glycoproteins. When the formulation comes into contact with saliva, it hydrates and swells, enabling drug release while adhering to the mucosal surface through physical interactions. For effective oral delivery, mucoadhesive systems should be small, flexible, and non-irritating, with good adhesion strength, high drug-loading capacity, and controlled release properties. Mucus, a viscoelastic secretion composed of proteins, lipids, enzymes, and ions, provides lubrication, adhesion, and a protective barrier. The effectiveness of a mucoadhesive system depends on the polymer’s capacity to interact with this layer and maintain prolonged residence time. In this regard, the surface characteristics of D-NS, such as swelling, wettability, and water absorption, play a key role in enhancing mucoadhesion and sustaining drug release [

10,

11,

12,

13].

A wide variety of mucoadhesive biomaterials have been explored for developing innovative drug delivery systems, including both synthetic and natural polymers. The most common synthetic examples are polyacrylic acid and cellulose derivatives such as Carbopol, polycarbophil, polymethacrylates, hydroxyethyl cellulose, and methyl cellulose. Other synthetic materials like poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)

and poly(vinyl alcohol) also exhibit mucoadhesive properties. Semi-natural polymers, including chitosan and natural gums such as guar, xanthan, gellan, carrageenan, pectin, and alginate, are also widely employed. While synthetic polymers often show strong adhesion, their limited biodegradability restricts long-term use. In contrast, natural polymers are biodegradable, biocompatible, safe, and cost-effective. Among them, polysaccharides display excellent mucoadhesive behavior due to their abundance of hydrophilic functional groups. Both synthetic and natural polymers containing hydrolytically or enzymatically labile bonds are degradable. Synthetic polymers offer several advantages, including predictable properties, batch-to-batch uniformity, and ease of chemical modification. However, their relatively high production cost and limited sustainability remain significant drawbacks. This has driven increasing attention toward natural polymers, which are biodegradable, biocompatible, and renewable, making them attractive candidates for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Starch, in particular, is a naturally abundant and versatile biopolymer, making it an attractive base material for mucoadhesive formulations and the synthesis of its derivatives, such as cyclodextrins (CDs) [

9,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

CDs are cyclic (α-1,4)-linked oligosaccharides composed of α-D-glucopyranose units, characterized by a hydrophilic outer surface and a relatively lipophilic internal cavity [

19]. They are biocompatible and biodegradable materials obtained through the enzymatic degradation of starch. The most common natural CDs are α-, β-, and γ-cyclodextrin, differing in the number of glucose units. However, native CDs exhibit certain limitations, including low aqueous solubility, suboptimal pharmacokinetics, and potential cytotoxicity. To overcome these drawbacks, CDs are often chemically modified through random substitution or polymerization reactions, leading to derivatives with improved solubility and broader applicability [

20,

21]. Cyclodextrin-based polymers, either soluble or insoluble, are synthesized by covalently linking two or more CD units using suitable cross-linking agents [

22]. Among these, insoluble CD-based polymers, also known as cyclodextrin nanosponges (CD-NS), have gained considerable attention as biocompatible polymeric nanocarriers. CD-NS are typically formed by reacting the hydroxyl groups of dextrin (D) with multifunctional cross-linking agents. Owing to their insoluble network, CD-NS can encapsulate a wide range of molecules, thereby enhancing the solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs and improving their bioavailability, stability, and therapeutic efficacy [

23,

24,

25]. The network architecture of CD-NS, rich in hydroxyl and carboxylic acid groups, imparts a strong affinity for water, enabling the formation of hydrogel-like structures [

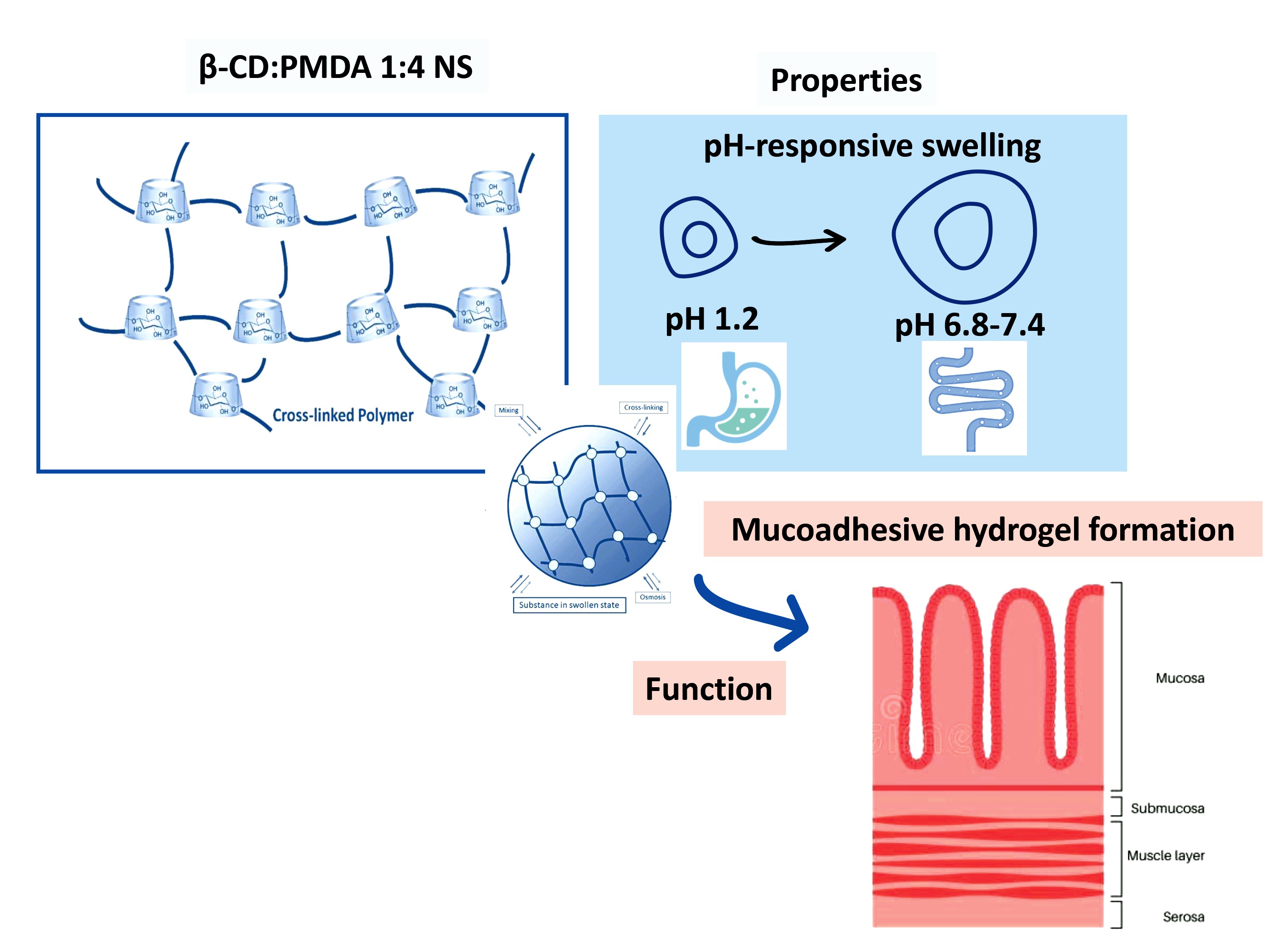

26]. In this context, CD-NS synthesized using pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) and citric acid (CA) as cross-linking agents were employed to develop mucoadhesive polymers. For comparison, linear dextrins such as GluciDex®2 (GLU2) and Linecaps (LC) were also incorporated as building blocks alongside β-cyclodextrin (β-CD). GLU2 and LC are maltodextrins, defined as hydrolyzed starch products with a dextrose equivalent (DE) value below 20. They are composed of D-glucose units (amylose and amylopectin) linked through α-1,4-glycosidic bonds with a few α-1,6-glycosidic linkages. The incorporated amylose tends to organize into a stable helical structure in aqueous environments [

27,

28]. The molar ratios between dextrin units and cross-linking agents were systematically varied (1:2, 1:4, and 1:8) to evaluate their influence on cross-linking density, determined using the Flory–Rehner theory, as well as on swelling behavior, pH sensitivity, and rheological properties. Among the tested formulations, the β-CD: PMDA (1:4) system exhibited the most favorable balance of mechanical and swelling characteristics and was therefore selected for further evaluation of mucoadhesive performance, in comparison with chitosan.

This study aimed to synthesize and characterize dextrin-based hydrogels with controlled swelling, pH sensitivity, and rheological and mucoadhesive properties suitable for oral drug delivery. This approach is particularly relevant for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [

29], where many therapeutic agents suffer from low oral bioavailability and require repeated subcutaneous or continuous parenteral administration. Developing mucoadhesive hydrogels capable of sustaining drug release through the oral route offers a promising strategy to enhance patient compliance and improve therapeutic outcomes.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Confirmation of Cross-Linking (FTIR and TGA)

Dextrin-based nanosponges (D-NS) are synthesized successfully by cross-linking the hydroxyl groups of β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) with pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) and citric acid (CA), as illustrated in

Figure S1. For the β-CD: PMDA nanosponge, the synthesis proceeded through a ring-opening reaction of PMDA. The anhydride ring was opened by a nucleophilic attack from the hydroxyl groups on the β-CD structure, facilitated by triethylamine (Et

3N) as a catalyst [

26]. This reaction led to the formation of carboxyl and ester groups within the polymer network. Citric acid (CA), a non-toxic cross-linking agent widely used for cross-linking starch, was also selected for cross-linking with β-CD. The β-CD: CA nanosponge was synthesized through the formation of a five-membered cyclic anhydride intermediate [

30]. During the initial step of cross-linking β-CD with CA, CA undergoes dehydration upon heating, resulting in water loss and formation of the cyclic anhydride. Esterification of β-CD with CA, catalyzed by sodium hypophosphite monohydrate (SHP), occurs efficiently at temperatures below 140°C. This reaction occurred as what has already been noticed before. The formation of synthesized D-NS at different ratios between the building block and cross-linker is confirmed by Fourier-transform infrared spectra (FTIR). The broad peak appearing at 3412 cm

-1 (

Figures S2 and S3) shows the presence of OH groups in unmodified β-CD (Dextrins) (ν (CH-OH) and (CH

2-OH)). The band at 1638 cm

-1 corresponds to the deformation of primary and secondary OH groups. Further in

Figure S2, the absorption band of the carbonyl group (C=O stretching) of PMDA appears at 1771 cm

-1. The polymerization reaction is confirmed by the shifting of the carbonyl group (C=O stretching) to 1723 cm

-1. The occurrence of a C=O peak at 1720 cm

-1, in the FTIR spectrum, is the characteristic feature of PMDA-based D-NS (

Figure S2) and CA-based D-NS (

Figure S3). In the spectrum of CA as the cross-linking agent (

Figure S3), the absorptions at 1728 cm

-1 and 1371 cm

-1 are assigned to the C=O stretching vibration, and at 1624 cm

-1 due to the carboxylic acid moieties.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is used to assess the thermal stability of synthesized D-NS. The second weight losses, occurring above 240

0C (

Figures S4 and S5), are related to the maximum degradation process of the cross-linked structure of D-NS. This indicates good thermal stability of D-NS (PMDA-based D-NS, and CA-based D-NS). The formation of D-NS can be explained by their lower thermal stability compared to the native dextrins (βCD, LC, and GLU

2) due to the presence of weaker bonds in modified dextrins (D-NS). The changes in the thermograms of the D-NS from the native dextrins are due to changes in their chemical structures.

2.2. Particle Size and Surface Charge

All synthesized nanocarriers were further characterized by measuring their zeta potential (

Table 2), average particle size, and polydispersity index (

Table 3). Zeta potential is an important parameter for predicting nanoparticle behavior

in vitro and

in vivo and for evaluating the stability of colloidal systems. Changes in zeta potential and particle size have significant biological implications, influencing cellular internalization, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution. The surface charge of nanoparticles strongly affects formulation stability, as electrostatic repulsion between particles can prevent aggregation.

Zeta potential measurements revealed that PMDA- and CA-based D-NS possess an anionic surface due to the carboxylic acid groups (-COOH), which gain charge through deprotonation until equilibrium is reached. The measured zeta potential values ranged from –16.00 mV to –32.60 mV, confirming the stability of the nanosuspensions and reflecting their surface properties.

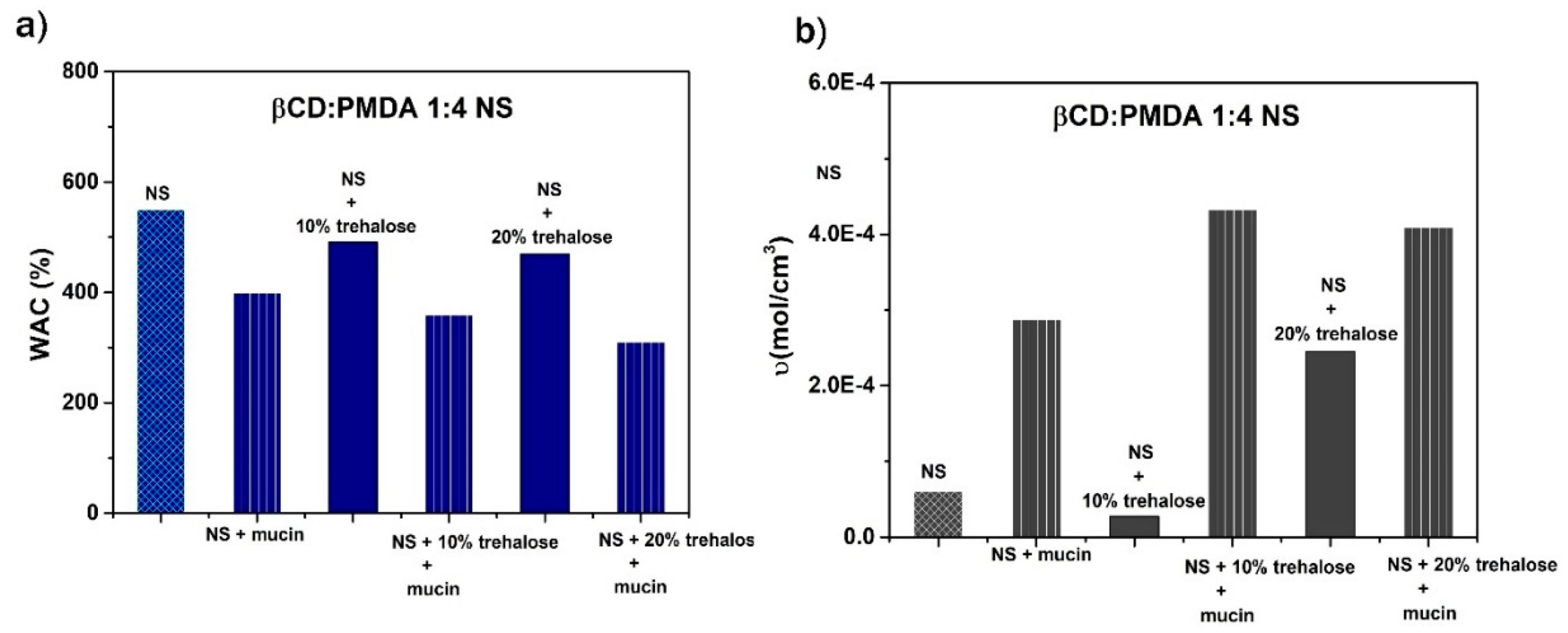

Figure 6.

The influence of mucin, 10% trehalose + mucin, and 20% trehalose + mucin on water absorption capacity (WAC, %) and cross-linking density (υ, mol/cm3) of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS).

Figure 6.

The influence of mucin, 10% trehalose + mucin, and 20% trehalose + mucin on water absorption capacity (WAC, %) and cross-linking density (υ, mol/cm3) of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS).

Table 3 presents the particle sizes of the various suspensions. The D-NS samples initially exhibited average particle sizes greater than 1 μm. The polydispersity index (PDI), which reflects the width of the particle size distribution, was below 0.5 for most PMDA- and CA-based D-NS suspensions, although a broader distribution was still observed. Particle size measurements indicate that the D-NS samples are polydisperse, as represented by a single z-average (Z-Ave) value, while the distribution often shows two or more peaks, each with its corresponding mean and width, as detailed in

Table 3. This polydispersity can be attributed to the relatively large particle size of the D-NS powders (>1 μm), which were initially ground only in a mortar. Therefore, both ball milling and high-pressure homogenization (HPH) were necessary to obtain uniform nanosuspensions of D-NS.

To reduce D-NS size and obtain nanosuspensions suitable for drug loading, D-NS (at a 1:4 molar ratio of dextrin to cross-linker) were processed using ball milling or high-pressure homogenization (HPH), considering the different characteristics of each polymer matrix. Stable nanosuspensions of GLU2:PMDA, GLU2:CA, and LC: CA were obtained by milling the D-NS powders followed by suspension in water. In contrast, β-CD: PMDA, β-CD: CA, and LC: PMDA required high-pressure homogenization to achieve stable nanosuspensions.

The average diameters of all the D-NS (

Table 4) were reduced after top-down methods (ball mill or HPH), reaching values between 178 to 442 nm. All resulting nanosuspensions exhibited favorable polydispersity index values (0.11–0.30), indicating a more homogeneous size distribution compared to the coarse powders.

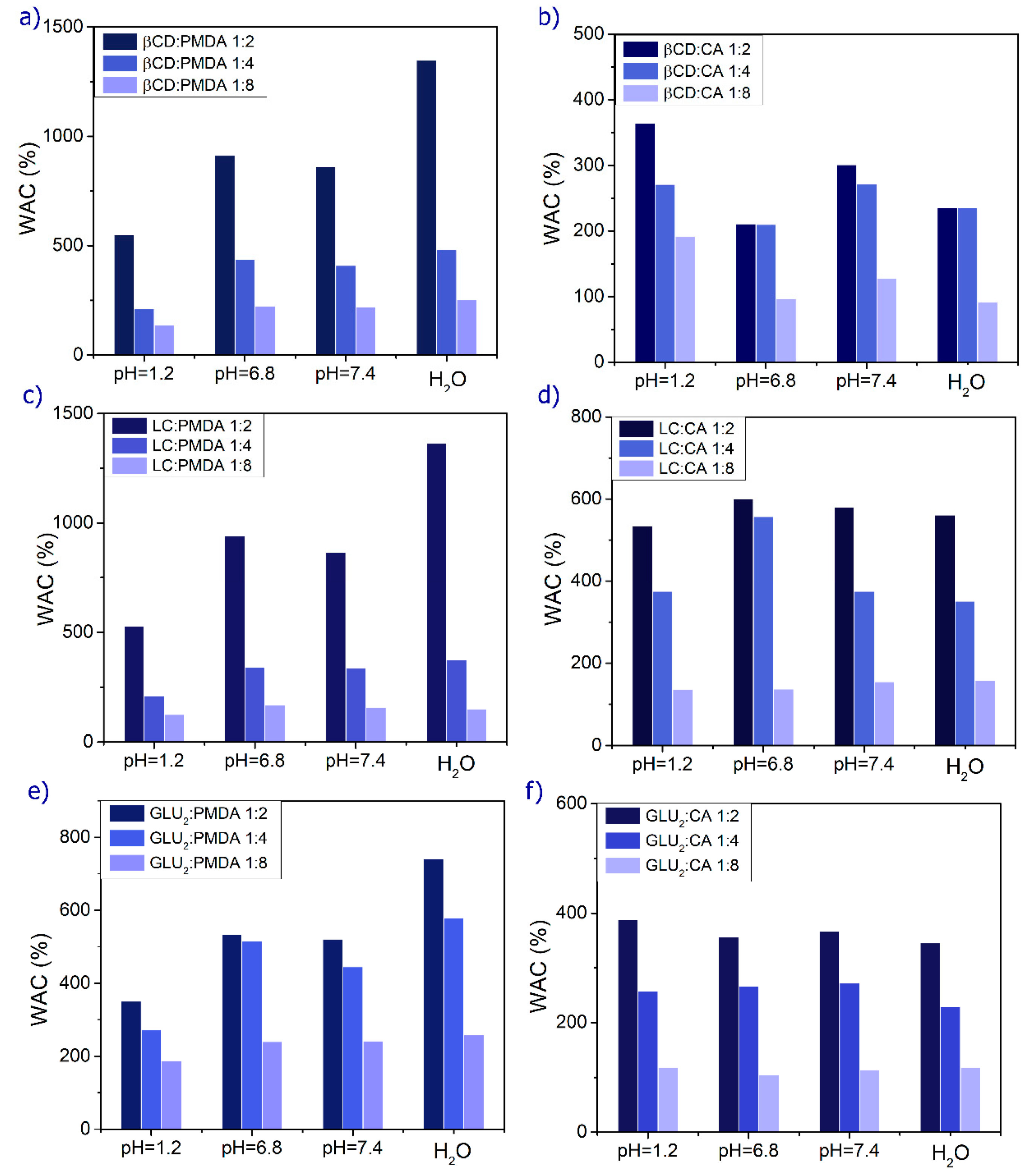

2.3. Swelling Behavior at Different pH

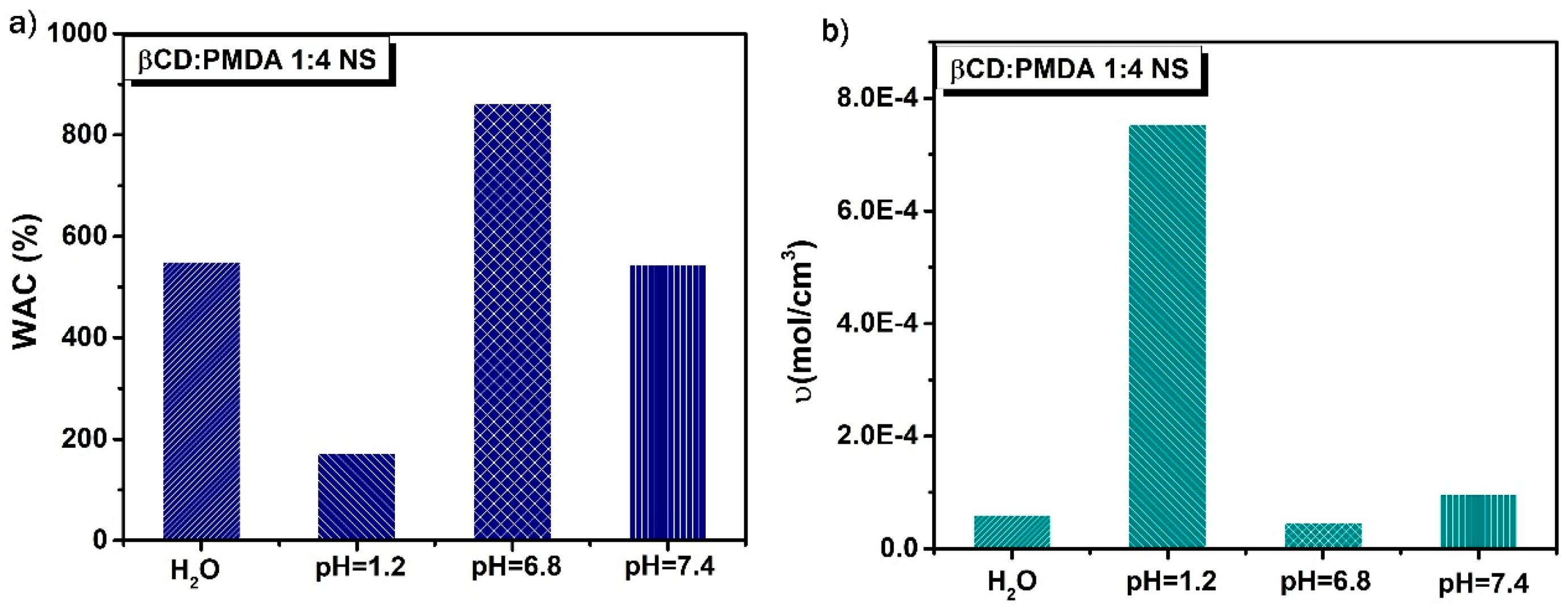

Water absorption capacity (WAC), also referred to as swelling capacity (S), significantly influences the surface properties, mobility, and mechanical characteristics of the polymer network, as well as the diffusion of solutes through it. Swelling behavior is particularly important for the application of nanocarriers in drug delivery, making it a favorable property for oral administration. PMDA-based D-NS (

Figure 1 and

Table S1) exhibits greater swelling capacity than CA-based D-NS due to the higher number of ionizable groups in its structure. This property can be leveraged to enhance the stability, solubility, and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs, as well as to control their release. The high encapsulation efficiency and slow-release kinetics are attributed either to electrostatic interactions between the carboxylic groups of the dianhydride bridges and polar moieties of hydrophilic drugs or to the formation of inclusion complexes with lipophilic drugs. The combination of dextrin and cross-linker determines the formation of nanochannels, the degree of hydrogel swelling, drug loading capacity, and drug release rate.

Figure 1 illustrates how formulation parameters such as pH, type of building block, and cross-linker content affect WAC. Increasing the relative amount of cross-linker (stoichiometric ratios of 2, 4, and 8) decreases WAC because higher cross-link density restricts polymer chain mobility, creating a more compact structure that limits water diffusion and reduces gel swelling.

Figure 1 also shows that the highest swelling occurs in water, and that D-NS exhibits pH-sensitive behavior due to its functional groups. As the pH shifts from neutral to acidic or basic, the swelling percentage decreases. In acidic conditions, –COO– groups convert to –COOH, enhancing hydrogen bonding among hydrophilic groups and increasing physical cross-linking, which reduces swelling. Conversely, at physiological pH (7.4), hydrogen bonding is disrupted, electrostatic repulsion among polymer chains increases, and the hydrogels swell more [

33].

2.4. Cross-Linking Density and Network Properties

The nanosponge β-CD: PMDA 1:4 NS was selected for drug studies due to its optimal balance between structural stability and swelling capacity. This polymer is also well known for its high drug-loading and encapsulation efficiency. The carboxylate side chains within the network are repelled by ions in the surrounding solution, leading to polymer expansion as the network minimizes charge interactions. As shown in

Figure 2a and

Table 5, the swelling potential of the polymer decreases under acidic conditions, such as those found in simulated gastric fluid, demonstrating that a pH-responsive swollen polymer system was successfully developed. This system can serve as a versatile oral delivery platform capable of encapsulating and protecting gastric-sensitive bioactives. Moreover,

Figure 2b and

Table 5 indicate that the cross-links within the polymer matrix are more stable at lower pH values, allowing the polymer chains to extend without detachment from the network. In contrast, at higher pH levels, the cross-links are more susceptible to rupture as the chains stretch, resulting in increased polymer diffusion into the surrounding solution [

34].

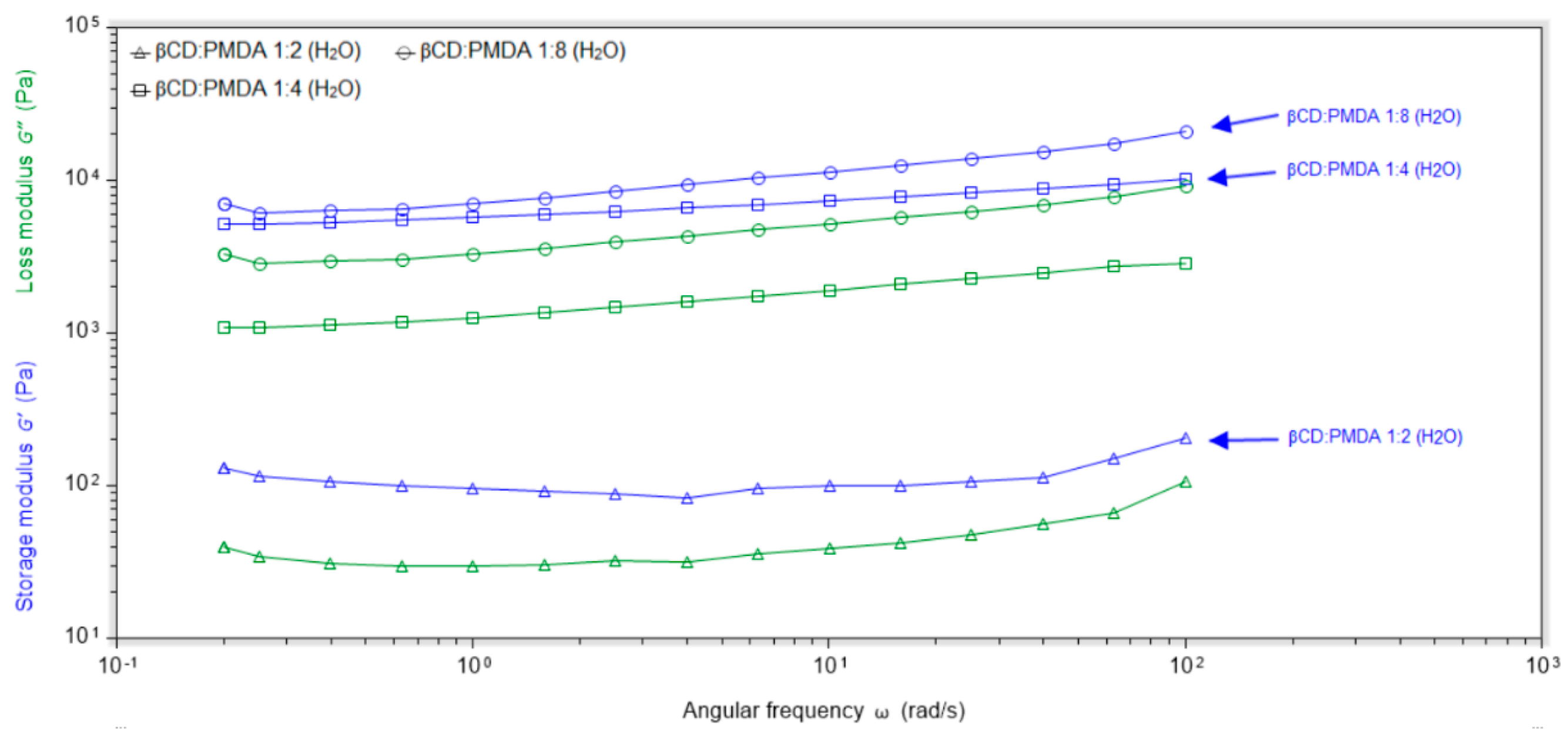

Controlling the rheological properties of polymeric formulations provides valuable insights into their physical characteristics, structure, stability, and drug release behavior. The rheological properties of candidate polymeric platforms for oral drug delivery were investigated using a TA Instruments Discovery HR 1 Rheometer equipped with a 20 mm diameter stainless steel plate geometry. Two key parameters for characterizing viscoelastic materials are the storage modulus (G′) and the loss modulus (G″), which were measured as a function of frequency in the Frequency Sweep test. In

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, G′ represents the elasticity of the polymers, while G″ reflects their viscous behavior.

The gel-state behavior of the nanosponges is confirmed by consistently higher G′ values compared to G″ across all angular frequencies (

Figures S6 and S7). These analyses also demonstrate that the hydrogels are pH-sensitive. The strength and elasticity of the gel, and consequently the release profile of the active ingredient, can be effectively tuned by selecting appropriate composition and production parameters. As noted previously, swelling is greater at basic pH than under acidic conditions. At higher pH, disruption of hydrogen bonding and ionization of COOH groups lead to increased swelling, which reduces elasticity.

Figure 3 shows that nanocarriers with the highest swelling capacities, β-CD: PMDA 1:4 NS (483%) and GLU2:PMDA 1:4 NS (578%), exhibit lower elastic behavior compared to the other formulations, as presented in

Table S1.

Furthermore,

Figure 4 shows that increasing the amount of cross-linker in the polymer network is associated with enhanced elastic behavior.

The cross-linking reaction is an effective strategy to control hydrogel properties, thereby influencing drug release rates. Swelling and mechanical characteristics are key factors in mucoadhesion. Due to the presence of carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, dextrin-based nanosponges are expected to be promising candidates for designing mucoadhesive drug delivery systems, as they can prolong the residence time of the formulation on the mucosal surface [

11,

35].

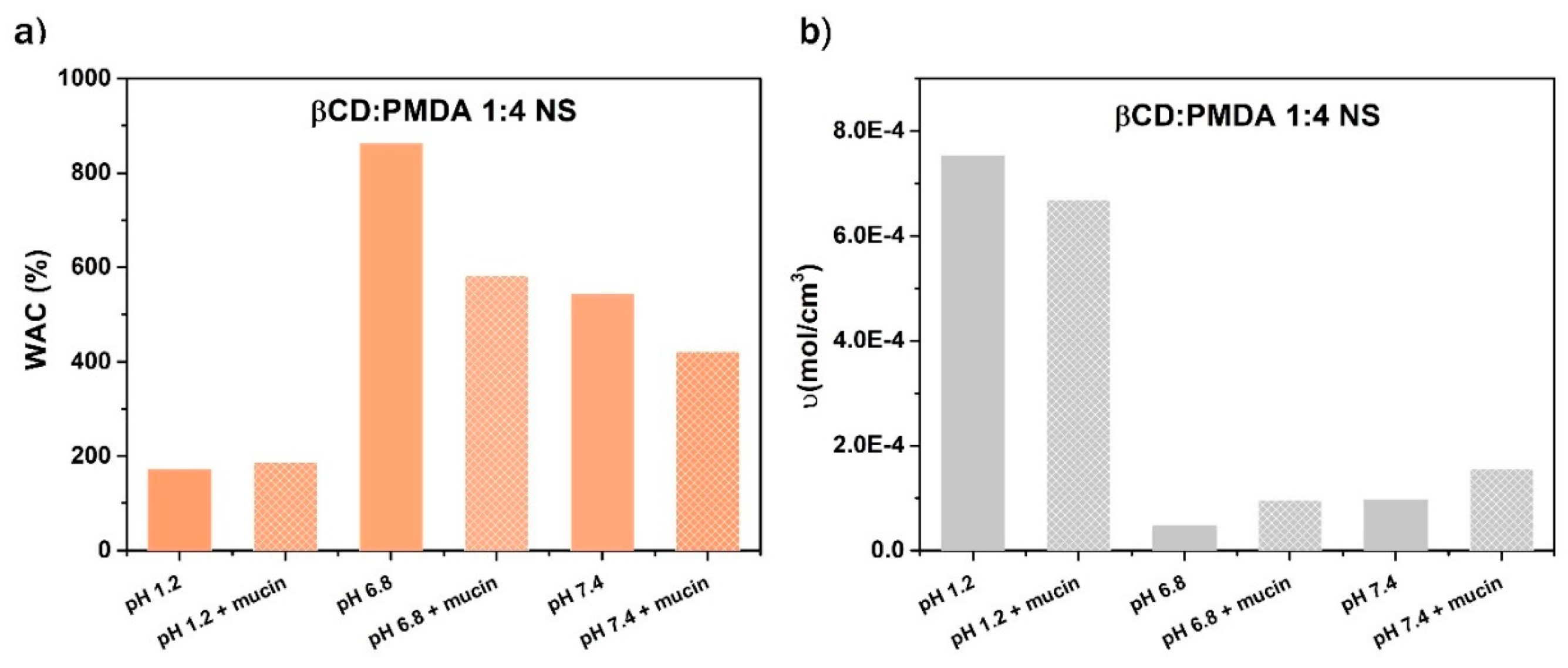

2.5. Mucoadhesive Behavior and Polymer–Mucin Interactions

As shown in

Figure 5a, the presence of mucin reduces the swelling of the hydrogel in simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and 7.4). This effect occurs because mucin forms a protective, gel-like barrier that acts as both a physical and chemical shield against toxins, pathogens, and other irritants. Such behavior underscores the importance of understanding mucus properties, which can be leveraged to enhance drug delivery and help prevent intestinal infections [

36]. The maximum swelling is observed at pH 6.8, likely because the polyanionic functional groups can disrupt hydrogen bonds between mucin polymers and compete for hydrogen-bonding sites with mucin glycoproteins, thereby weakening intra- and inter-network cross-links and interactions [

37].

Furthermore, 10% and 20% trehalose can be employed as cryoprotectants to prevent particle aggregation of dextrin-based nanosponges, since stability is a key parameter for their use as drug delivery systems. As shown in Figures 6 a) and b), trehalose at both concentrations did not significantly affect the water absorption capacity but influenced the cross-linking density as its concentration varied.

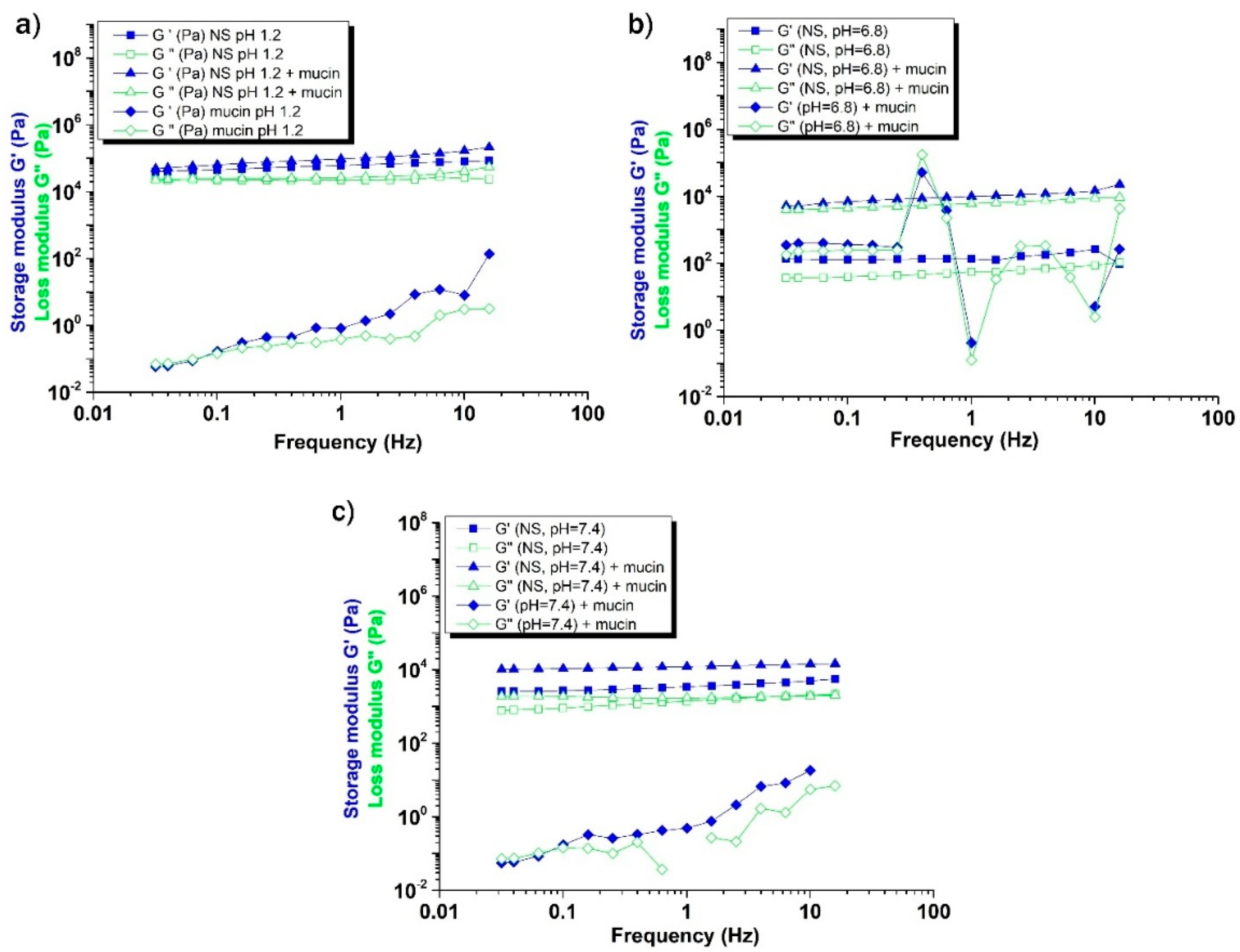

As shown in

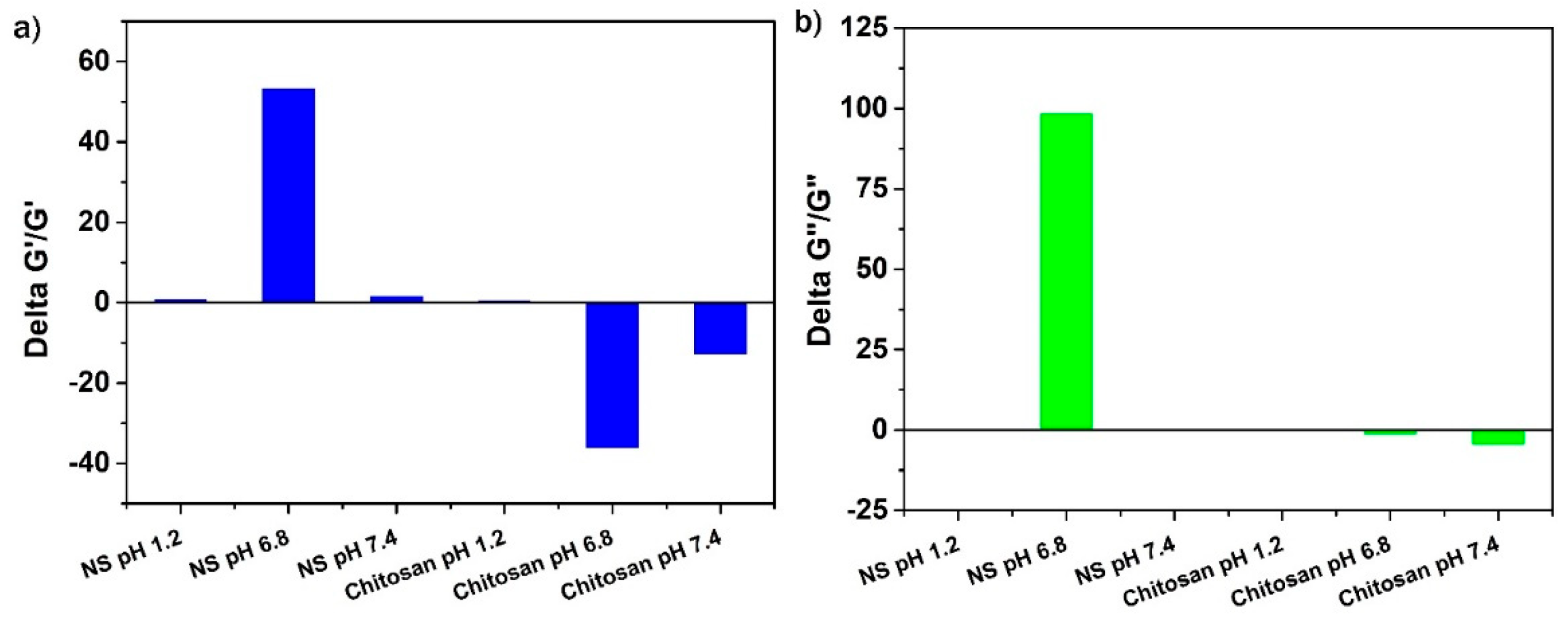

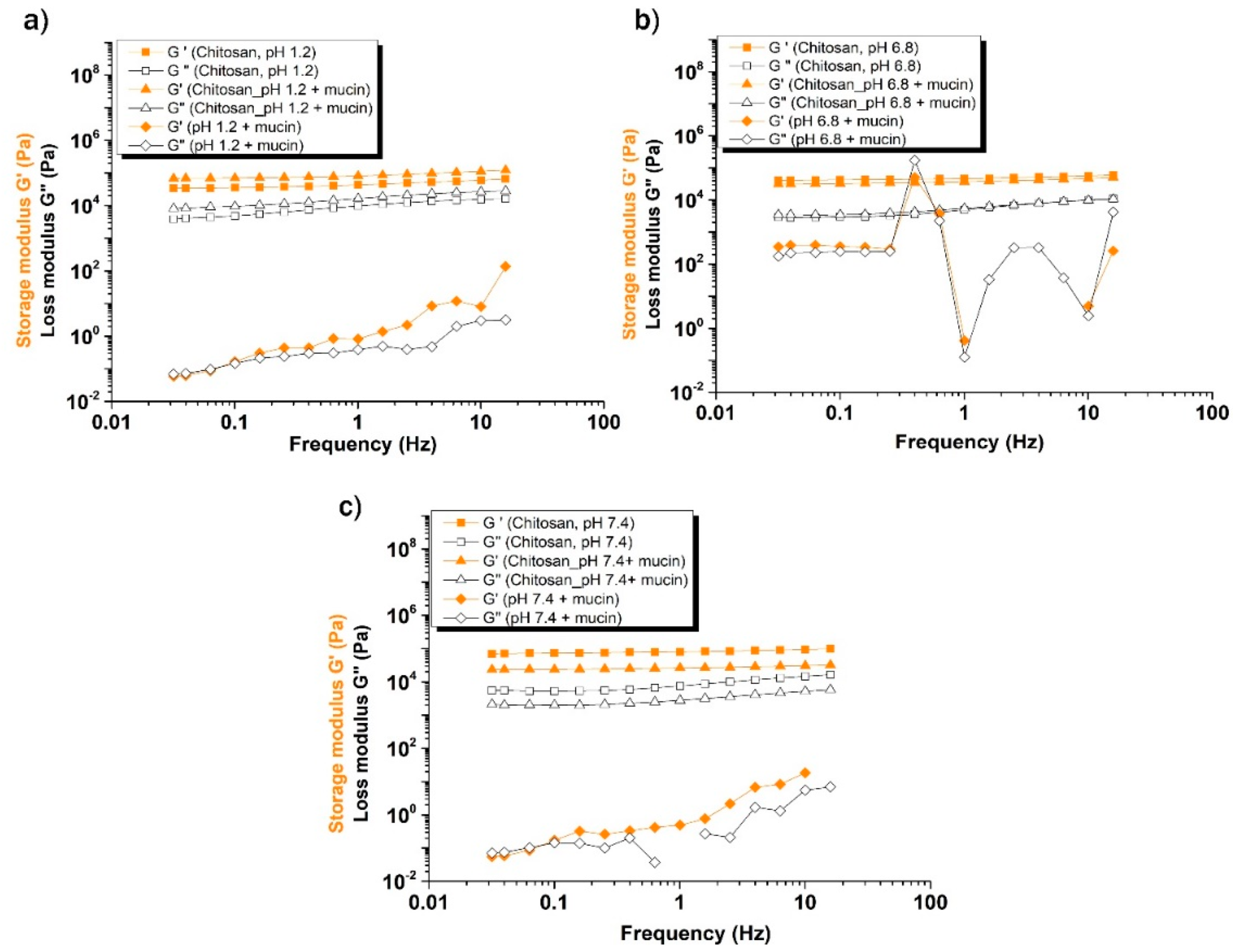

Figure 7, the viscoelastic moduli (G′ and G″) of the β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS) + mucin mixture increased in both a) simulated gastric fluid, and b), c) simulated intestinal fluids, compared to the individual polymer and mucin solutions. The formation of a cross-linked gel network is confirmed by its rheological behavior, which exhibits minimal frequency dependence, with G′ and G″ remaining nearly constant across a wide frequency range.

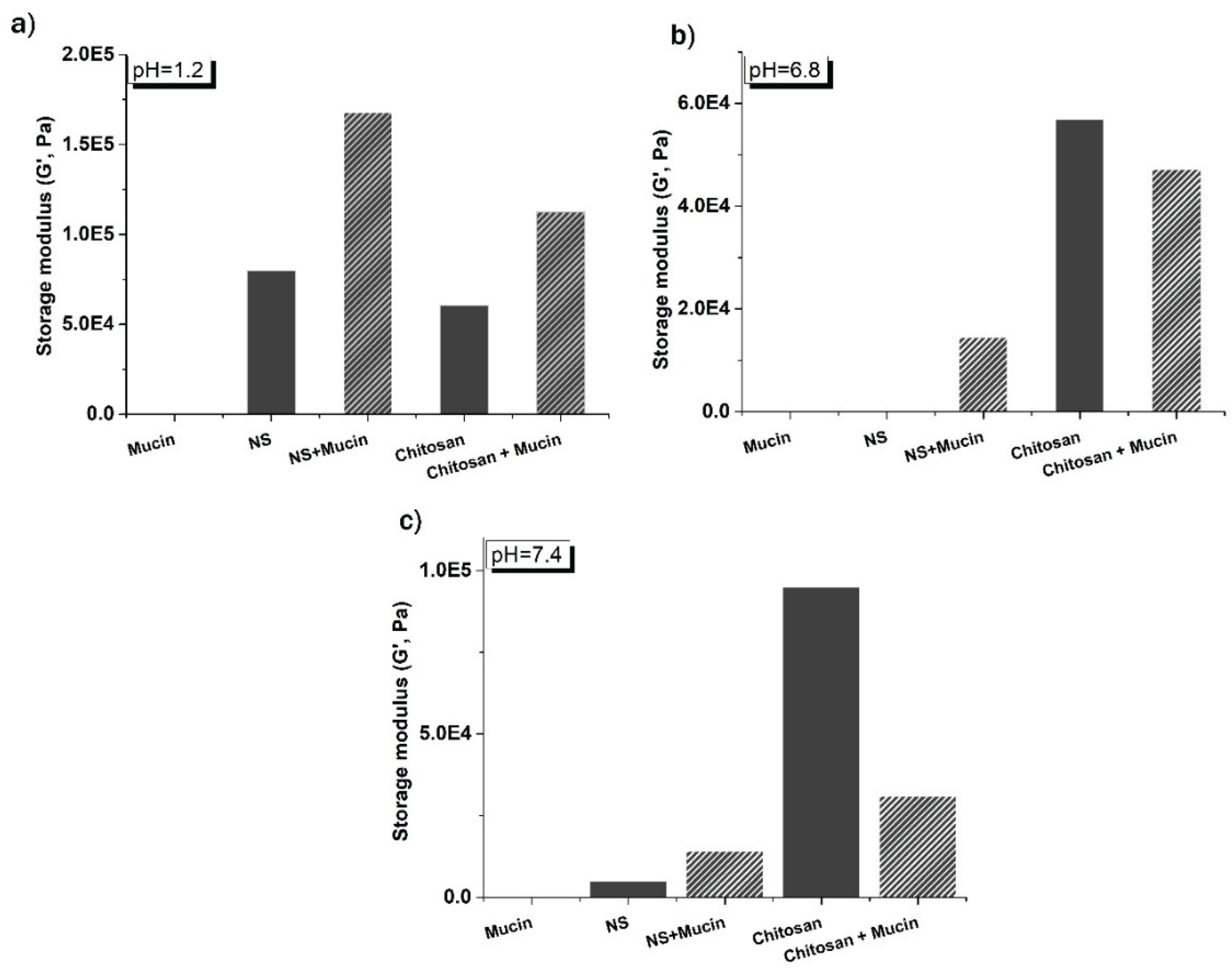

Figure 8a shows that both G′ and G″ values are higher for the chitosan–mucin mixture in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2) compared to chitosan and mucin alone, as well as to the mixtures in simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and 7.4) presented in

Figure 8b,c [

38]. This observation is consistent with literature reports indicating that electrostatic complexation between chitosan and mucin is favored under acidic to mildly acidic conditions (pH 2.4–6.3) [

39].

Rheological synergism has been suggested as an effective

in vitro parameter for evaluating the mucoadhesive properties of polymers. A higher rheological synergism value indicates a stronger interaction between the polymer and mucin [

40]. The mixtures of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS) and mucin exhibited positive ΔG′/G′ and ΔG″/G″ values, indicating favorable polymer–mucin interactions. Among all tested conditions, the β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS)–mucin mixture at pH 6.8 showed the highest positive rheological synergism, suggesting stronger mucoadhesive behavior. In contrast, negative rheological synergism values were observed for the chitosan–mucin mixtures at pH 6.8 and 7.4, confirming previous literature reports that chitosan is mucoadhesive only within a limited pH range and remains soluble primarily under acidic conditions (pH < 6). At higher pH values, chitosan tends to precipitate, which can compromise the performance of carrier systems [

41,

42]. At pH 6.8, the high and positive ΔG′ value further supports strong mucin–polymer interactions, leading to the formation of a continuous, swollen, and homogeneous network. This behavior contrasts with that at pH 1.2, where more compact and segregated complexes were formed, limiting elastic response. A low or negative ΔG′ reflects weak interactions between mucin and polymer [

43]. Overall, these findings highlight the potential of β-CD:PMDA 1:4 nanosponge (NS) as polymer with promising mucoadhesive capabilities.

Figure 9.

Relative rheological synergism, at a frequency of 10 Hz, expressed as a) ΔG’/G’ and b) ΔG”/G” for β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS) and chitosan in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4).

Figure 9.

Relative rheological synergism, at a frequency of 10 Hz, expressed as a) ΔG’/G’ and b) ΔG”/G” for β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS) and chitosan in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4).

Figure 10 and

Table 6 show that polymer–mucus G′ values at 10 Hz are highest in samples swollen in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2). The most pronounced increase in synergistic interactions, as previously observed, was detected with β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS). At low pH, carboxylic acid groups in the polymer can form hydrogen bonds, resulting in labile intermolecular cross-links. As the pH increases, these hydrogen bonds are replaced by ionic interactions, leading to disruption of the hydrogen-bonded network. Consequently, mucus–polymer mixtures lose structural integrity and progressively exhibit more viscous behavior. Interactions between mucus and mucoadhesive polymers are primarily mediated by secondary bonding, mainly hydrogen bonding, and physical entanglement. A strengthened gel network can form spontaneously when the polymer is overhydrated, as the presence of excess water facilitates additional network links. Fully hydrated mucus gels allow more interactions between polymer chains and mucin glycoproteins, contributing to a stronger network. Polymers with a high density of hydrogen-bonding groups can therefore interact more effectively with mucin. Previous studies have suggested that polymer concentration can influence the extent of rheological synergism, which will be explored in our future work [

31,

44].

3. Conclusions

A series of dextrin-based nanosponges was successfully synthesized using pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) and citric acid (CA) as cross-linking agents at varying stoichiometric ratios (1:2, 1:4, and 1:8). The resulting polymers exhibited pH-responsive and mucoadhesive properties, attributed to their carboxylic and saccharide functional groups, and they demonstrated the ability to form stable hydrogels under physiological conditions. After top-down processing (ball milling or high-pressure homogenization), particle sizes were reduced to 178–442 nm with uniform distributions (PDI 0.11–0.30) and stable surface charges (–16.00 to –32.60 mV). Swelling studies revealed pH-dependent behavior (simulated gastric fluid, pH 1.2, and simulated intestinal fluids, pH 6.8 and pH 7.4), with reduced swelling under acidic conditions due to enhanced hydrogen bonding and cross-linking, while physiological pH promoted higher expansion through electrostatic repulsion. The presence of mucin further decreased swelling, confirming polymer–mucin interactions. Rheological synergism analysis identified β-CD: PMDA 1:4 nanosponge as the most mucoadhesive formulation, showing the highest positive ΔG′/G′ values at pH 6.8. These findings highlight the potential of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 nanosponge as a promising mucoadhesive carrier for oral drug delivery. Its pH sensitivity, controlled swelling, and strong interaction with mucin suggest suitability for sustained release applications targeting the gastrointestinal tract. Future studies will focus on drug loading efficiency, in vivo pharmacokinetics, and bioavailability to validate their effectiveness for oral administration, particularly in neurodegenerative disease therapy.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

β-cyclodextrin (β-CD, Mw=1134.98 g/mol), GluciDex®2 (GLU2, DE value of 2; Mw=~200000 g/mol), and KLEPTOSE® Linecaps (LC, Mw=~12000 g/mol) (kindly supplied as a gift by Roquette, Lestrem, France), are used as building blocks, whereas pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) and citric acid (CA) as multifunctional cross-linking agents. Pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA, 97.00%); dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, ≥99.90%); triethylamine (Et3N, ≥99.00%); acetone (C3H6O, ≥99.00% (GC)), sodium hypophosphite monohydrate (NaPO2H2*H2O, ≥99.00%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37.00%); sodium hydroxide (NaOH, pellets); mucin (from porcine stomach), chitosan (low molecular weight), sodium chloride (NaCl, ACS, ISO, Reag. Ph Eur), potassium chloride (KCl, ≥99.50% (AT)), are all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). The citric acid (C6H8O7, 99.90%) is purchased from VWR Chemicals BDH (Milano, Italy). Disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate (Na2HPO4*2H2O, 99.00%) and potassium phosphate monobasic (KH2PO4, 98.00%) are purchased from Italia Carlo Erba S. P. A. Simulated gastric fluid (SGF, pH 1.2) is prepared by dissolving 1.00 g of NaCl and adding 3.50 mL of concentrated HCl, then diluting the solution to 500 mL with deionized water. Simulated intestinal fluid (SIF, pH 6.8) is prepared by mixing 6.80 g of KH₂PO₄ in 250 mL of water with 0.94 g of NaOH dissolved in 118 mL of water, and then diluting the mixture to a final volume of 500 mL. Simulated intestinal fluid (SIF, pH 7.4) is prepared by dissolving 4.00 g of NaCl, 0.10 g of KCl, 0.90 g of Na₂HPO₄·2H₂O, and 0.12 g of KH₂PO₄ in 500 mL of deionized water. Deionized water and water purified by reverse osmosis (MilliQ water, Millipore) with a resistivity above 18.20 MΩcm-1, and dispensed through a 0.22 μm membrane filter, are used throughout the studies.

4.2. Synthesis of Dextrin-Based Polymers

Dextrin-based nanosponges (D-NS) are chemically cross-linked polymers synthesized by reacting the dextrin building blocks with a cross-linking agent under specific conditions (

Figure S1 in Supplementary Material).

4.2.1. Synthesis of PMDA-Based D-NS

The synthesis was carried out according to the procedure previously described [

26]. The synthesis process began by dissolving 4.89 g of anhydrous β-CD, GLU

2, or LC in 20 mL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, ≥99.9% ) in a round-bottom flask. Once a clear, uniform solution was achieved, 2.5 mL of triethylamine (Et₃N, ≥99%) was added as a catalyst, followed by the addition of PMDA (PMDA, 97%) as the cross-linking agent in molar ratios of 2, 4, or 8 per glucose unit (

Table 1). The polymerization occurred rapidly at room temperature, and after 24 hours, the resulting solid was purified using a Buchner filtration system with Whatman No. 1 filter paper (Whatman, Maidstone, UK). The by-products were then removed through Soxhlet extraction with acetone for approximately 48 hours. Finally, a homogeneous white powder of PMDA-based D-NS was obtained, yielding over 95%.

4.2.2. Synthesis of CA-Based D-NS

The synthesis was carried out according to the procedure previously described [

30]. The synthesis of nanosponge was carried out by dissolving 4.40 g of anhydrous β-CD, GLU

2, or LC in 15 mL of deionized water with the subsequent addition of 0.80 g sodium hypophosphite monohydrate (SHP, ≥99%) as a catalyst, followed by the addition of CA (99.9%) as the cross-linking agent in molar ratios of 2, 4, or 8 per glucose unit (

Table 1). The reaction was conducted in an oven under vacuum at temperatures of 140°C and 100°C until a solid, insoluble mass was formed. The resulting solid was purified using a Buchner filtration system with deionized water and acetone to eliminate any by-products. Ultimately, a homogeneous white powder of CA-based D-NS was obtained, achieving a yield of 60%.

4.3. Characterization

The synthesized polymers were characterized by the following techniques:

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis- using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum Spotlight 100 FTIR spectrophotometer equipped with Spectrum software. The FTIR spectra are gained in the spectral range of 4000-650 cm-1, at a spectral resolution of 4 cm-1, and a sample/ background scan number of 8. FTIR spectra are obtained using a versatile Attenuated Total Reflectance mode (FTIR-ATR) sampling accessory with a diamond crystal plate.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)-using a TA Instrument Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA), Q500, from room temperature up to 800 0C, under nitrogen (N2) flow, and with a heating ramp rate of 10 0C/min. The gas flows applied in the balance and furnace section are 40 mL/min and 60 mL/min. About 10 mg of the sample are weighed on the aluminum pan for analysis.

Zeta Potential and Particle Size Analyses- Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements are carried out using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS with DTS Version 5.03, a software package (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK). Approximately 1 mg of the sample is suspended in 1 mL of Milli-Q water, and average sizes are expressed in terms of intensity-weighed size distributions based on hydrodynamic diameters (dH). To obtain a more homogenous nanoparticle distribution and to reduce NS size, aqueous suspensions of the synthesized nanosponges (β-CD: PMDA and β-CD: CA) were prepared employing two top-down methods (ball milling and high-shear homogenizer) to reduce NS size. During the ball milling (60 minutes) and high-shear homogenizer (15 minutes) processes, the nanosponges were suspended in water at a concentration of 1 mg/mL.

4.4. Swelling Studies

The swelling kinetics of the synthesized nanosponges were analyzed by monitoring their weight increase upon immersion in aqueous solutions. Swelling measurements were conducted by immersing 0.3 g of dry powder in deionized water and at both simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4) in 15-mL test tubes. Initially, the mixtures were blended using a Vortex Mixer. The test tubes were then sealed and kept at room temperature. Once equilibrium swelling was achieved, the mixtures were centrifuged to separate the water-bound material from the unabsorbed free water. The supernatant was removed, and any residual free water was carefully blotted with tissue paper before recording the weight. Swelling measurements were performed in duplicate. The swelling percentage (%S) was calculated using the following Equation (1):

where m

t is the weight of the swollen sample, and m

o is the initial weight of the dry sample.

4.5. Preparation of Mucin Samples

To investigate the dominant interactions between mucin and the polymers, mucin suspensions were prepared by dispersing 250 mg of mucin and 500 mg of polymer in 10 mL of deionized water, and at both simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluid (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4) in 15-mL test tubes. The mixtures were briefly vortexed to ensure homogeneity and then allowed to hydrate and swell for 2 h at room temperature. After 2 h, the samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant was carefully removed. To assess the effect of trehalose on particle aggregation and its influence on swelling behavior, cross-linking density, and polymer–mucin interactions, trehalose was added at 10% and 20% (w/v). Chitosan was used as a reference to compare mucoadhesive capacity.

4.6. Cross-Linking Density Determination

The previously prepared swollen samples permitted the calculation of the polymer volume fraction in the equilibrium-swollen polymer (

υ2m) that is used to calculate the cross-linking density (

υ) using the Flory–Rehner theory. The number of cross-links per unit volume in a polymer network is defined as cross-linking density, and it is calculated using the following Equation (2) as previously described in our previous article [

26].

4.7. Rheological Analysis

The rheological measurements are performed in a Rheometer TA Instruments Discovery HR. The instrument is equipped with a 20 mm diameter stainless steel plate geometry and Peltier plate temperature control. Frequency sweep measurement is conducted in the range of 100 to 0.2 rad/s with a stress amplitude of 2%, acquiring 5 points per decade. The oscillatory shear mode is used to determine the shear modulus (G), specifically, the storage modulus (G’) and the loss modulus (G’’) of the swollen NSs as a function of frequency (Frequency Sweep test). The swollen sample was positioned between the upper parallel plate and the stationary surface with a 0.5 mm gap and conditioned at 25

0C for 300 s prior to measurement, following the established protocol [

26].

4.8. Mucoadhesion Studies

The rheological synergism parameters, which are the differences between the experimentally measured viscoelastic values of the mucin-polymer mixtures and the theoretical values obtained by summing the viscoelastic components of polymer and mucin, were calculated as described in the literature (Equations 3.1 and 3.2) [

31,

32]:

Also, the relative rheological synergism, which expresses the relative enhancement in viscoelastic behavior concerning the separate polymer and mucin solutions, was estimated as (Equations 4.1 and 4.2):

The storage and loss modulus determined at the frequency of 10.04 Hz were used in the calculation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H., M.A., R.C., and F.T.; methodology, G.H.; software, G.H.; validation G.H. and S. E.-R..; formal analysis, G.H. and S. E.-R.; investigation G.H.; resources, M.A., R.C., F.C., and F.T.; data curation, G.H. and M. A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.H. and S. E.-R.; writing—review and editing, G.H., S.E.-R., I. H., M.A., R.C., A.A., A.M., F.T., and F.C.; visualization, G.H., S.E.-R., I. H., M.A., R.C., A.A., A.M., F.T., and F.C.; supervision, M.A., R.C., F.T. and F.C.; project administration, M.A., R.C., F.T. and F.C.; funding acquisition, M.A., R.C., and F.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The research activity of G.H. is part of the NODES project, which has received funding from the MUR–M4C2 1.5 of PNRR with the grant agreement no. ECS00000036. The authors acknowledge their support from Project CH4.0 under the MUR program “Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023–2027” (CUP: D13C22003520001). A.M is receiving a Ramon y Cajal Contract (Grant RYC2023-043196-I) funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the FSE+.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| β-CD |

β-Cyclodextrin |

| LC |

KLEPTOSE® Linecaps |

| GLU2 |

GluciDex®2 |

| CA |

Citric Acid |

| PMDA |

Pyromellitic Dianhydride |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| CDs |

Cyclodextrins |

| D-NS |

Dextrin-based Nanosponges |

| NS |

Nanosponge |

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| PD |

Parkinson’s disease |

| DMSO |

Dimethylsulfoxide |

| Et₃N |

Triethylamine |

| SHP |

Sodium Hypophosphite Monohydrate |

| FTIR |

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| TGA |

Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| DLS |

Dynamic Light Scattering |

| N2

|

Nitrogen |

| S |

Swelling |

| WAC |

Water Absorption Capacity |

| G |

Shear Modulus |

| G’ |

Storage Modulus |

| G” |

Loss Modulus |

| ΔG’ |

Rheological Synergism |

| ΔG’/G’ |

Relative Rheological Synergism |

| -COOH |

Carboxylic Acid Groups |

| PDI |

Polydispersity Index |

| Z-Ave |

Z-average |

| HPH |

High-Pressure Homogenization |

References

- J. Lou et al., “Advances in Oral Drug Delivery Systems: Challenges and Opportunities,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 15, no. 484, pp. 1–22, 2023.

- D. Vllasaliu, “Oral administration.pdf,” Front. Drug Deliv., pp. 1–3, 2025.

- J. Reinholz, K. Landfester, and V. Mailänder, “The challenges of oral drug delivery via nanocarriers,” Drug Deliv., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 1694–1705, 2018.

- S. Bashiardes and C. Christodoulou, “Orally Administered Drugs and Their Complicated Relationship with Our Gastrointestinal Tract,” Microorganisms, vol. 12, no. 242, pp. 1–18, 2024.

- M. Azman, A. H. Sabri, Q. K. Anjani, M. F. Mustaffa, and K. A. Hamid, “Intestinal Absorption Study: Challenges and Absorption Enhancement Strategies in Improving Oral Drug Delivery,” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 1–24, 2022.

- R. Kumar, T. Islam, and M. Nurunnabi, “Mucoadhesive carriers for oral drug delivery,” J Control Release, vol. 351, pp. 504–559, 2022.

- S. Alaei and H. Omidian, “Mucoadhesion and Mechanical Assessment of Oral Films,” Eur. J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 159, pp. 1–17, 2021.

- J. Bagan et al., “Mucoadhesive Polymers for Oral Transmucosal Drug Delivery: A Review,” Curr. Pharm. Des., vol. 18, no. 34, pp. 5497–5514, 2012.

- R. Sharma et al., “Recent advances in biopolymer-based mucoadhesive drug delivery systems for oral application,” J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol., vol. 91, pp. 1–18, 2024.

- J. D. Smart, “The basics and underlying mechanisms of mucoadhesion,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 57, no. 11, pp. 1556–1568, 2005.

- B. Chatterjee, N. Amalina, P. Sengupta, and U. K. Mandal, “Mucoadhesive Polymers and Their Mode of Action: A Recent Update,” J. Appl. Pharm. Sci., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 195–203, 2017.

- Z. Jawadi, C. Yang, Z. S. Haidar, P. L. Santa Maria, and S. Massa, “Bio-Inspired Muco-Adhesive Polymers for Drug Delivery Applications,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 14, pp. 1–28, 2022.

- B. M. Boddupalli, Z. N. K. Mohammed, R. Nath A., and D. Banji, “Mucoadhesive drug delivery system: An overview,” J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res., vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 381–387, 2010.

- L. Serra, J. Doménech, and N. Peppas, “Engineering Design and Molecular Dynamics of Mucoadhesive Drug Delivery Systems as Targeting Agents,” Eur J Pharm Biopharm, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 1–7, 2009.

- Z. Davoudi, G. Kali, D. Braun, M. H. Azizi, and A. Bernkop-Schnürch, “Highly thiolated corn starch for enhanced mucoadhesion and permeation,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 680, pp. 1–12, 2025.

- K. Ahmad et al., “Enhancing mucoadhesion: Exploring rheological parameters and texture profile in starch solutions, with emphasis on micro-nanofiber influence,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 275, no. 1299, pp. 1–19, 2024.

- D. R. Lu, C. M. Xiao, and S. J. Xu, “Starch-based completely biodegradable polymer materials,” Express Polym. Lett., vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 366–375, 2009.

- <i>18. </i>B. D. Ulery, L. S. B. D. Ulery, L. S. Nair, and C. T. Laurencin, “Biomedical Applications of Biodegradable Polymers Bret,” J Polym Sci B Polym Phys, vol. 49, no. 12, pp. 832–864, 2011.

- T. Loftsson and M. E. Brewster, “Pharmaceutical Applications of Cyclodextrins. 1. Drug Solubilization and Stabilization,” J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 85, no. 10, pp. 1017–1025, 1996.

- G. Kali, S. Haddadzadegan, and A. Bernkop-Schnürch, “Cyclodextrins and derivatives in drug delivery: New developments, relevant clinical trials, and advanced products,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 324, pp. 1–23, 2024.

- Z. Liu, L. Ye, J. Xi, J. Wang, and Z. Feng, “Cyclodextrin polymers: Structure, synthesis, and use as drug carriers,” Prog. Polym. Sci., vol. 118, pp. 1–24, 2021.

- M. Agnes, E. Pancani, M. Malanga, E. Fenyvesi, and I. Manet, “Implementation of Water-Soluble Cyclodextrin-Based Polymers in Biomedical Applications: How Far Are We?,” Macromol. Biosci., vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 1–26, 2022.

- P. Sherje, B. R. Dravyakar, D. Kadam, and M. Jadhav, “Cyclodextrin-based nanosponges: A critical review,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 173, no. 1, pp. 37–49, 2017.

- Krabicová et al., “History of cyclodextrin nanosponges,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 1–23, 2020.

- F. Trotta, M. Zanetti, and R. Cavalli, “Cyclodextrin-based nanosponges as drug carriers,” Beilstein J. Org. Chem., vol. 8, pp. 2091–2099, 2012.

- G. Hoti et al., “Effect of the Cross-linking Density on the Swelling and Rheological Behavior of Ester-Bridged β-Cyclodextrin Nanosponges,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 1–20, 2021.

- Y.-J. Wang and L. Wang, “Structures and Properties of Commercial Maltodextrins from Corn, Potato, and Rice Starches,” Starch/Staerke, vol. 52, no. 7–8, pp. 296–304, 2000.

- M. Münster et al., “Comparative in vitro and in vivo taste assessment of liquid praziquantel formulations,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 529, no. 1–2, pp. 310–318, 2017.

- D. G. Gadhave et al., “Neurodegenerative disorders: Mechanisms of degeneration and therapeutic approaches with their clinical relevance,” Ageing Res. Rev., vol. 99, 2024.

- G. Hoti et al., “A Comparison between the Molecularly Imprinted and Non- Molecularly Imprinted Cyclodextrin- Based Nanosponges for the Transdermal Delivery of Melatonin,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 1543, pp. 1–27, 2023.

- F. Madsen, K. Eberth, and J. D. Smart, “A rheological examination of the mucoadhesive/mucus interaction: the effect of mucoadhesive type and concentration,” J. Control. Release, vol. 50, no. 1–3, pp. 167–178, 1998.

- P. Sriamornsak and N. Wattanakorn, “Rheological synergy in aqueous mixtures of pectin and mucin,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 474–481, 2008.

- W. Wang, J. Wang, Y. Kang, and A. Wang, “Synthesis, swelling and responsive properties of a new composite hydrogel based on hydroxyethyl cellulose and medicinal stone,” Compos. Part B, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 809–818, 2011.

- T. M. FitzSimons, E. V. Anslyn, and A. M. Rosales, “Effect of pH on the Properties of Hydrogels Cross - Linked via Dynamic Thia-Michael Addition Bonds,” ACS Polym. Au, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 129–136, 2022.

- M. A. Güler, M. K. Gök, A. K. Figen, and S. Özgümüş, “Swelling, mechanical and mucoadhesion properties of Mt/starch-g-PMAA nanocomposite hydrogels,” Appl. Clay Sci., vol. 112–113, pp. 44–52, 2015.

- H. M. Yildiz, L. H. M. Yildiz, L. Speciner, C. Ozdemir, D. E. Cohen, and R. L. Carrier, “Food-associated Stimuli Enhance Barrier Properties of Gastrointestinal Mucus,” Biomaterials, vol. 54, pp. 1–8, 2015.

- E. Y. Chen, D. Daley, Y.-C. Wang, M. Garnica, C.-S. Chen, and W.-C. Chin, “Functionalized carboxyl nanoparticles enhance mucus dispersion and hydration,” Sci. Rep., vol. 2, 2012.

- M. Collado-González, Y. G. Espinosa, and F. M. Goycoolea, “Interaction Between Chitosan and Mucin: Fundamentals and Applications,” Biomimetics, vol. 4, no. 32, pp. 1–20, 2019.

- M. Ahmad, C. Ritzoulis, W. Pan, and J. Chen, “Biologically-relevant interactions, phase separations and thermodynamics of chitosan–mucin binary systems,” Process Biochem., vol. 94, no. December 2019, pp. 152–163, 2020.

- S. Rossi, F. Ferrari, M. C. Bonferoni, and C. Caramella, “Characterization of chitosan hydrochloride-mucin rheological interaction: influence of polymer concentration and polymer:mucin weight ratio,” Eur. J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 479–485, 2001.

- T. M. M. Ways, W. M. Lau, and V. V. Khutoryanskiy, Chitosan and its derivatives for application in mucoadhesive drug delivery systems, vol. 10. 2018.

- M. K. Amin and J. S. Boateng, “Enhancing Stability and Mucoadhesive Properties of Chitosan Nanoparticles by Surface Modification with Sodium Alginate and Polyethylene Glycol for Potential Oral Mucosa Vaccine Delivery,” Mar. Drugs, vol. 20, pp. 1–22, 2022.

- V. M. de Oliveira Cardoso, M. P. D. Gremião, and B. S. F. Cury, “Mucin-polysaccharide interactions: A rheological approach to evaluate the effect of pH on the mucoadhesive properties,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 149, pp. 234–245, 2020.

- R. G. Riley et al., “An investigation of mucus / polymer rheological synergism using synthesised and characterised poly (acrylic acid)s,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 217, pp. 87–100, 2001.

Figure 1.

The swelling of PMDA and CA-based D-NS in deionized water and solutions with pH levels of 1.2, 6.8, and 7.4.

Figure 1.

The swelling of PMDA and CA-based D-NS in deionized water and solutions with pH levels of 1.2, 6.8, and 7.4.

Figure 2.

The swelling of PMDA-based D-NS in deionized water, simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4).

Figure 2.

The swelling of PMDA-based D-NS in deionized water, simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4).

Figure 3.

Storage (G’) and loss (G’’) modulus versus angular frequency for β-CD: PMDA 1:4 NS; β-CD: CA 1:4 NS; LC: PMDA 1:4 NS; LC: CA 1:4 NS; Glu2:PMDA 1:4 NS; Glu2:CA 1:4 NS; 0.8 mm gap size. Nanocarriers are swollen in deionized water.

Figure 3.

Storage (G’) and loss (G’’) modulus versus angular frequency for β-CD: PMDA 1:4 NS; β-CD: CA 1:4 NS; LC: PMDA 1:4 NS; LC: CA 1:4 NS; Glu2:PMDA 1:4 NS; Glu2:CA 1:4 NS; 0.8 mm gap size. Nanocarriers are swollen in deionized water.

Figure 4.

Storage (G’) and loss (G’’) modulus versus angular frequency for β-CD: PMDA 1:2 NS; β-CD: PMDA 1:4 NS; and β-CD: PMDA 1:8 NS; 0.8 mm gap size. Nanocarriers are swollen in deionized water.

Figure 4.

Storage (G’) and loss (G’’) modulus versus angular frequency for β-CD: PMDA 1:2 NS; β-CD: PMDA 1:4 NS; and β-CD: PMDA 1:8 NS; 0.8 mm gap size. Nanocarriers are swollen in deionized water.

Figure 5.

a) Water absorption capacity (WAC, %), and b) cross-linking density (υ, mol/cm3) of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS) and β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS)+mucin in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4).

Figure 5.

a) Water absorption capacity (WAC, %), and b) cross-linking density (υ, mol/cm3) of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS) and β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS)+mucin in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4).

Figure 7.

The frequency dependence of the storage modulus (G’) and the loss modulus (G”) of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS), β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS)+ mucin, and mucin in simulated a) gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (b) pH 6.8 and c) pH 7.4.

Figure 7.

The frequency dependence of the storage modulus (G’) and the loss modulus (G”) of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS), β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS)+ mucin, and mucin in simulated a) gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (b) pH 6.8 and c) pH 7.4.

Figure 8.

The frequency dependence of the storage modulus (G’) and the loss modulus (G”) of chitosan, chitosan+ mucin, and mucin in simulated a) gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (b) pH 6.8 and c) pH 7.4.

Figure 8.

The frequency dependence of the storage modulus (G’) and the loss modulus (G”) of chitosan, chitosan+ mucin, and mucin in simulated a) gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (b) pH 6.8 and c) pH 7.4.

Figure 10.

Rheological properties of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS) and chitosan in a) simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and b), c) simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4), 10 Hz.

Figure 10.

Rheological properties of β-CD: PMDA 1:4 (NS) and chitosan in a) simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and b), c) simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4), 10 Hz.

Table 2.

Zeta Potential (ZP) values of D-NS.

Table 2.

Zeta Potential (ZP) values of D-NS.

| Samples |

ZP (mV) |

| GLU2:CA 1:2 |

0.96 |

| GLU2:CA 1:4 |

0.25 |

| GLU2:CA 1:8 |

1.55 |

| LC: CA 1:2 |

1.56 |

| LC: CA 1:4 |

2.08 |

| LC: CA 1:8 |

1.80 |

| β-CD: CA 1:2 |

0.80 |

| β-CD: CA 1:4 |

0.23 |

| β-CD: CA 1:8 |

1.49 |

| β-CD: PMDA 1:2 |

9.49 |

| β-CD: PMDA 1:4 |

0.32 |

| β-CD: PMDA 1:8 |

1.14 |

| LC: PMDA 1:2 |

1.25 |

| LC:PMDA 1:4 |

0.80 |

| LC:PMDA 1:8 |

0.98 |

| GLU2:PMDA 1:2 |

0.65 |

| GLU2:PMDA 1:4 |

0.69 |

| GLU2:PMDA 1:8 |

0.15 |

Table 3.

Particle Size values of D-NS before the top-down process (ball mill or HPH).

Table 3.

Particle Size values of D-NS before the top-down process (ball mill or HPH).

| Samples |

Z-Ave (d.nm)

|

PdI |

Pk 1 Mean Int (d.nm) |

Pk 2 Mean Int (d.nm) |

| GLU2:CA 1:2 |

3341.0153.4 |

0.382 0.006 |

1848.0 172.9 |

5444 200.3 |

| GLU2:CA 1:4 |

2512.0237.4 |

0.464 0.037 |

2120.0 804.0 |

5167 45.54 |

| GLU2:CA 1:8 |

1644.073.2 |

0.820 0.241 |

1061.0 42.2 |

1851 2868 |

| LC: CA 1:2 |

666.310.8 |

0.485 0.01 |

1463.0 401.5 |

262.7 149.3 |

| LC: CA 1:4 |

2094.099.5 |

0.428 0.055 |

1594.0 386 |

3529 2903 |

| LC: CA 1:8 |

965.654.7 |

0.639 0.107 |

1959.0 874.7 |

1694 2177 |

|

β-CD: CA 1:2

|

2145.087.1 |

0.514 0.040 |

2469.0 1137.0 |

3634 2241 |

|

β-CD: CA 1:4

|

2507.055.4 |

0.322 0.039 |

1910 83.7 |

5503 52.37 |

|

β-CD: CA 1:8

|

2097.0221.1 |

0.481 0.074 |

1987 552.7 |

182.5 21.34 |

|

β-CD: PMDA 1:2

|

742.5103.2 |

0.757 0.156 |

667 63.26 |

136.4 2.689 |

|

β-CD: PMDA 1:4

|

790.67.1 |

0.496 0.025 |

1511 441.3 |

243 134.2 |

|

β-CD: PMDA 1:8

|

1141.025.4 |

0.468

|

2017 478.9 |

344.5 145.4 |

| LC:PMDA 1:2 |

581.99.8 |

0.422 0.009 |

837.3 91.92 |

1664 2550 |

| LC:PMDA 1:4 |

762.413.9 |

0.358 0.058 |

1247 206.6 |

212.7 35.88 |

| LC:PMDA 1:8 |

126743.8 |

0.544 0.042 |

1716 1265 |

3159 2385 |

| GLU2:PMDA 1:2 |

1212.035.0 |

0.498 0.031 |

2035 683.7 |

278.2 172.2 |

| GLU2:PMDA 1:4 |

804.048.0 |

0.571 0.010 |

2557 795 |

381.6 330.7 |

| GLU2:PMDA 1:8 |

964.570.3 |

0.872 0.012 |

1036 120.8 |

247.8 81.34 |

Table 4.

Physico-chemical parameters of D-NS nanosuspensions.

Table 4.

Physico-chemical parameters of D-NS nanosuspensions.

| Samples |

Z-Ave±SD

(nm)

|

PDI |

Zeta Potential ±SD (mV) |

| GLU2:CA 1:4 |

186.60 ± 2.54 |

0.25 ± 0.02 |

-34.31 ± 0.78 |

| LC: CA 1:4 |

298.90 ± 9.08 |

0.21 ± 0.03 |

-28.58 ± 0.52 |

|

β-CD: CA 1:4

|

441.70 ± 9.87 |

0.26 ± 0.02 |

-22.75 ± 0.43 |

|

β-CD: PMDA 1:4

|

286.60 ± 3.94 |

0.20 ± 0.01 |

-30.21 ± 0.75 |

| LC:PMDA 1:4 |

382.76 ± 13.96 |

0.30 ± 0.04 |

-30.16 ± 1.28 |

| GLU2:PMDA 1:4 |

177.80 ± 2.66 |

0.11 ± 0.01 |

-22.50 ± 0.76 |

Table 5.

WAC (%) and υ (mol/cm3) of βCD:PMDA 1:4 NS.

Table 5.

WAC (%) and υ (mol/cm3) of βCD:PMDA 1:4 NS.

|

Sample (βCD: PMDA 1:4 NS)

|

WAC (%) |

υ(mol/cm3)

|

| Deionized H2O |

550 |

6.04E-5 |

| Gastric fluid (pH=1.2) |

172 |

7.53E-4 |

| Intestinal fluid (pH=6.8) |

863 |

4.64E-5 |

| Intestinal fluid (pH=7.4) |

544 |

9.65E-5 |

Table 6.

G’ (Pa) of samples in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4), 10 Hz, and calculated interaction terms (Delta G’/G’).

Table 6.

G’ (Pa) of samples in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), and simulated intestinal fluids (pH 6.8 and pH 7.4), 10 Hz, and calculated interaction terms (Delta G’/G’).

| Samples |

G’ (Pa) (pH=1.2) |

G’ (Pa) (pH=6.8) |

G’ (Pa) (pH=7.4) |

Delta G’/G’ (pH=1.2) |

Delta G’/G’ (pH=6.8) |

Delta G’/G’ (pH=7.4) |

| Mucin |

8.05 |

4.95 |

18.22 |

|

|

|

| NS |

80009.00 |

260.29 |

4940.29 |

|

|

|

| NS + Mucin |

167957.00 |

14444.50 |

14132.70 |

1.09 |

53.45 |

1.85 |

| Chitosan |

60420.80 |

56871.10 |

94889.30 |

|

|

|

| Chitosan + Mucin |

112273.00 |

47256.30 |

30918.20 |

0.64 |

-36.26 |

-12.90 |

Table 1.

The amount of the cross-linking agent is used to prepare various D-NS molar ratios.

Table 1.

The amount of the cross-linking agent is used to prepare various D-NS molar ratios.

| Nanosponges |

Molar ratio (Dextrin: PMDA)

|

Glucose unit: PMDA |

m (PMDA), g |

|

β-CD/LC/GLU2: PMDA

|

1:2 |

1:0.29 |

1.87 |

| 1:4 |

1:0.57 |

3.75 |

| 1:8 |

1:1.14 |

7.51 |

|

β-CD/LC/GLU2: CA

|

1:2 |

1:0.29 |

1.49 |

| 1:4 |

1:0.57 |

2.98 |

| 1:8 |

1:1.14 |

5.96 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).