1. Introduction

In the evolving landscape of organizational psychology, the pursuit of emotionally intelligent and culturally attuned workplaces has become increasingly vital. As organizations grapple with rising levels of occupational stress and mental health challenges, burnout has emerged as a critical concern. Defined as a pervasive syndrome with symptoms of mental exhaustion decreasing work energy associated with cognitive and emotional impairments, whose mental distancing process over time leads to dysfunctional attitudes and feelings of aversion to work, burnout affects employees across sectors and geographies, with particularly high prevalence in public service, education, and healthcare [

1,

2,

3]. Its consequences—ranging from absenteeism and turnover to reduced productivity and compromised well-being—underscore the urgency of identifying protective factors that can mitigate its impact.

Among the most promising constructs in this domain is companionate love, an emotional culture characterized by expressions of affection, compassion, tenderness, and caring within professional relationships [

4,

5]. Far from being a sentimental or peripheral phenomenon, companionate love has been empirically linked to enhanced team cohesion, resilience, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment [

6,

7]. It fosters a climate of psychological safety, enabling employees to navigate interpersonal challenges and organizational demands with greater emotional resources. Moreover, recent studies suggest that high-quality listening and emotionally supportive leadership can cultivate perceptions of companionate love, further amplifying its positive effects [

5].

Complementing this emotional dimension are organizational culture practices (OCP), which encompass structural and relational mechanisms such as intersectoral communication, institutional care, collaborative leadership, and mental health promotion. These practices serve as contextual resources that shape employees’ perceptions of support, inclusion, and belonging, thereby influencing their engagement and vulnerability to burnout [

8,

9]. In Brazilian public organizations, however, cultural traits such as bureaucratism, centralized authority, and resistance to innovation often hinder the development of emotionally intelligent practices [

10,

11,

12]. Understanding how OCP interacts with emotional culture and individual outcomes is, therefore, essential for advancing organizational health in this context.

The Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) theory offers a robust framework for examining these dynamics. Originally developed to explain burnout, JD–R posits that job demands—such as workload, emotional labor, and role ambiguity—consume energy and lead to strain, while job resources—such as autonomy, feedback, and social support—satisfy psychological needs and promote engagement [

13,

14]. The theory has since evolved to incorporate personal resources (e.g., self-efficacy, hope, emotional intelligence) and proactive behaviors such as job crafting, which allow employees to reshape their tasks and relationships to better align with their strengths and values [

15,

16]. These expansions have deepened our understanding of how individuals and organizations can work together to foster resilience and well-being.

Work engagement, defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption [

17], has emerged as a central construct in positive organizational psychology. It is associated with higher performance, lower turnover intentions, and greater life satisfaction [

18,

19]. In Brazilian samples, engagement has been positively predicted by job crafting and personal resources, and negatively associated with workplace harassment and excessive demands [

15,

20]. Importantly, engagement has also been shown to mediate the relationship between emotional culture and burnout, suggesting that fostering engagement may be a key mechanism through which organizations can buffer stress and enhance well-being [

6].

Despite these insights, a notable gap remains in the Brazilian literature regarding the integrated examination of companionate love, organizational culture practices, work engagement, and burnout. Most studies have explored these constructs in isolation, leaving unanswered questions about their interrelations and collective impact. Addressing this gap, the present study employs a quantitative, exploratory, and correlational design to investigate the relationships among these variables in a diverse sample of Brazilian workers. By leveraging validated psychometric instruments and advanced network modeling techniques, this research aims to uncover the structural and emotional pathways that contribute to occupational well-being and resilience.

Specifically, the study aims to investigate whether companionate love and organizational culture practices are linked to higher engagement and lower burnout, and whether engagement serves as a mediator in the relationship between emotional culture and burnout. Network analysis enables the identification of direct and indirect pathways, centrality indices, and the most efficient routes of influence among constructs. This methodological approach provides a nuanced understanding of the psychological architecture of workplace well-being, moving beyond linear models to capture the complexity of human experience in organizational settings.

Ultimately, this research contributes to the theoretical advancement of organizational psychology by integrating emotional, cultural, and motivational constructs within a unified framework. It also offers practical implications for leaders, HR professionals, and policymakers seeking to design emotionally intelligent and culturally responsive workplaces. By illuminating the role of companionate love and organizational practices in shaping engagement and mitigating burnout, the study underscores the transformative potential of relational and cultural resources in promoting sustainable work environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative, exploratory, and correlational design to examine relationships among affective and organizational variables in workplace settings. Data were collected using validated psychometric instruments and analyzed through descriptive statistics, correlational tests, and network modeling.

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

Data were collected online from June to August 2025 using a structured questionnaire hosted on SurveyMonkey. The final sample comprised 649 workers from multiple Brazilian states and organizational sectors, with a predominance of public sector employees. Participants were recruited through professional networks and social media, and all provided informed consent prior to participation.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic and Occupational Characteristics

Sociodemographic and occupational information was collected through a structured questionnaire. Participants reported their state of residence (27 Brazilian states and the Federal District), gender (female, male, prefer not to respond), educational attainment (elementary education, high school, undergraduate degree, or postgraduate degree including master’s, doctorate, or postdoctoral studies), occupational group (security, managers, educators, health professionals, higher education professionals in other areas, clergy and spiritual assistants, technical workers, administrative staff, service professionals such as sales, arts, culture, law, IT, or journalism, agricultural and forestry workers, industrial workers, specialized operators, and maintenance/transport/repair workers), type of organization (public, private, third sector/NGO, or self-employed/professional practice), and organizational sector (industry, services, commerce). In addition, participants indicated their organizational tenure (years of employment at the current organization) and work modality (on-site, remote, or hybrid).

2.3.2. Companionate Love

Companionate love in the workplace was assessed with the Emotional Culture at Work Scale (ECET), the Brazilian adaptation of the Companionate Love Scale originally proposed by Barsade and O’Neill [

4]. The instrument comprises four items, each representing a distinct affective expression: affection (e.g., “Employees show emotional closeness through attentive listening, encouragement, recognition of achievements, and supportive words”), care (e.g., “Employees provide practical help or spontaneous support when a colleague is in need, demonstrating concern for others’ well-being”), compassion (e.g., “Employees show sensitivity to colleagues’ suffering through emotional support, empathic listening, and presence in difficult moments”), and tenderness (e.g., “Employees express gentleness in interactions through considerate gestures, a welcoming look, and a kind tone of voice”). Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always). In the present study, the scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α = .90 and polychoric α = .93. Given the brevity of the scale (four items), McDonald’s ω estimates were unstable and therefore not reported, in line with psychometric best practices.

2.3.3. Burnout

Burnout symptoms were measured using the Burnout Assessment Tool – BAT-12 [

1], which captures four interrelated dimensions of the syndrome: exhaustion (e.g., “At work, I feel mentally exhausted,” “I find it difficult to recover my energy after a working day,” “At work, I feel physically exhausted”), mental distancing (e.g., “I struggle to find enthusiasm for my job,” “I feel averse to my work,” “I am cynical about what my job means to others”), cognitive impairment (e.g., “At work, I have difficulty maintaining focus,” “I find it hard to concentrate,” “I make mistakes because my mind is on other things”), and emotional impairment (e.g., “At work, I feel unable to regulate my emotions,” “I do not recognize myself in the way I react emotionally,” “I may overreact unintentionally while working”). Responses were given on a 5-point Likert frequency scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). In the present study, the BAT-12 demonstrated excellent internal consistency for the total scale (Cronbach’s α = .91; polychoric α = .93; McDonald’s ω = .94–.95), supporting its reliability for assessing burnout symptoms in this occupational sample.

2.3.4. Work Engagement

Work engagement was measured using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9), adapted and validated for Brazil by Vazquez et al., [

21]. The scale comprises nine items that assess three dimensions: vigor (e.g., “At my work, I feel bursting with energy,” “At my job, I feel strong and vigorous”), dedication (e.g., “I am enthusiastic about my job,” “My work inspires me,” “I am proud of the work that I do”), and absorption (e.g., “I am immersed in my work,” “I get carried away when I am working”). Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert frequency scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always, every day). In the present study, the UWES-9 demonstrated excellent internal consistency for the total score (Cronbach’s α = .95; polychoric α = .96; McDonald’s ω = .97–.98), providing strong support for its reliability in assessing work engagement in this sample.

2.3.5. Organizational Culture Practices (OCP)

To assess organizational culture practices, we developed a 12-item scale grounded in the literature on emotional culture and organizational practices [

4,

8,

9]. Respondents indicated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The items were designed to capture four thematic dimensions: Collaboration and Teamwork (e.g., “My organization values teamwork,” “My organization encourages collaboration among colleagues,” “My organization fosters solidarity and cooperative behaviors”; one reverse-coded item assessed competitiveness), Leadership and Participation (e.g., “Organizational leadership promotes respectful and human relations”; one reverse-coded item assessed centralized decision-making), Intersectoral Communication (e.g., “Communication across sectors occurs openly and transparently”), and Belonging and Care (e.g., “Employees feel a sense of belonging,” “My organization values actions of care among colleagues,” “My organization undertakes initiatives to promote mental health”). Two items (competitiveness and centralized decision-making) were reverse-coded prior to analysis. This structure allowed us to evaluate both the overall construct of organizational culture practices and its theoretically grounded subdimensions. In the present study, the OCP scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .90; polychoric α = .92; McDonald’s ω = .93–.95), supporting its reliability as a measure of workplace organizational culture practices.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study followed the Brazilian National Health Council’s ethical guidelines for human subjects research (Resolution No. 510/2016) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (CAAE: 64195322.0.0000.5334). All participants were informed about the study’s objectives, confidentiality safeguards, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in RStudio using statistical packages such as qgraph, bootnet, and other relevant tools. Initially, descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, medians, and frequencies, were computed for sociodemographic and occupational variables. To examine zero-order associations between sociodemographic factors and the four primary constructs—Companionate Love (CL), Organizational Culture Practices (OCP), Engagement, and Burnout—Pearson’s correlations were calculated, with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals derived from 2,000 resamples. Interconstruct relationships were further explored through correlation analyses, and discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which compares the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) from one-factor confirmatory factor analyses with the squared correlations (r²) between constructs.

Group comparisons were conducted using Kruskal–Wallis tests, followed by Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc procedures, to evaluate differences in construct scores across sociodemographic categories. In addition, network analysis was performed by applying the EBICglasso estimator (γ = 0.50) to polychoric correlation matrices generated with cor_auto, thereby enabling the estimation of partial correlation networks. In these networks, nodes represented constructs, while edges indicated regularized partial correlations, with thickness reflecting magnitude and color indicating direction. Shortest path analysis was employed to identify the most efficient indirect routes connecting the variables.

Finally, centrality indices—including strength, expected influence, closeness, and betweenness centrality—were computed to assess the relative importance of constructs within the network. The stability of these indices was evaluated using case-dropping bootstrap procedures with 2,000 resamples, and stability coefficients (CS) were interpreted as acceptable when ≥ .25 and good when ≥ .50.

2.6. Data Availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request. Due to confidentiality agreements with participants, the dataset is not publicly deposited but can be shared in anonymized form for replication purposes.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 649 Brazilian workers aged 18 to 79 years (M = 43.4, SD = 11.1; median = 44). Participants were distributed across all Brazilian regions, with the most significant representation in Rio Grande do Sul (30.5%), followed by the Federal District (8.6%), São Paulo (8.3%), Alagoas (6.9%), Santa Catarina (6.5%), Minas Gerais (5.7%), Paraná (5.2%), and Rio de Janeiro (4.9%). Regarding gender, 65.8% of the participants identified as female and 34.2% as male. Educational attainment was high, with 76.0% holding a postgraduate degree, 15.7% having completed undergraduate education, 7.9% having finished high school, and 0.5% having completed only elementary school. In occupational terms, 45.1% were employed in higher or technical education, 13.4% in other professional areas, 12.6% in managerial positions, and 10.2% in healthcare, with smaller proportions in technical, administrative, industrial, and service-related roles. Concerning organizational type, 59.0% worked in the public sector, 34.8% in the private sector, 5.4% were self-employed or freelancers, and 0.8% were employed in NGOs or the third sector. The service sector predominated (90.8%), followed by industry (6.5%) and commerce (2.8%). The average organizational tenure was 10.5 years (SD = 8.5), ranging from 1 to 42 years. Most participants worked in person (60.4%), while 33.3% worked in hybrid arrangements and 6.3% entirely remotely.

3.2. Zero-Order Correlations with Sociodemographic Variables

Table 1 presents the Pearson correlations between sociodemographic variables—gender, age, educational level, occupational group, organizational type/sector, tenure, and work modality—and the four primary constructs: Companionate Love (CL), Organizational Culture Practices (OCP), Work Engagement, and Burnout. Correlation coefficients range from −1 to +1, with values closer to zero indicating weaker associations. Although the magnitudes of most correlations were small, some were statistically significant. Female participants reported slightly higher OCP scores than male participants. Age was positively and significantly associated with Engagement, indicating that older participants tended to report marginally greater engagement at work. Educational level was positively associated with Engagement and negatively associated with Burnout, suggesting that participants with higher levels of education reported slightly higher Engagement and lower Burnout. The occupational group also showed a weak but significant positive association with OCP, indicating that specific job categories perceived their organizations as having stronger emotional culture practices. While some of these relationships were statistically significant, the small magnitudes of all coefficients indicate that sociodemographic characteristics explained only a minimal proportion of the variance in the primary constructs. This pattern supports the decision to exclude these variables from subsequent network analyses, focusing on the relationships among the psychological constructs themselves.

3.2. Interconstruct Correlations and Discriminant Validity

The correlations among the four primary constructs, along with descriptive statistics and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values, are displayed in

Table 2. The strongest positive correlation was observed between CL and OCP (r = 0.56), indicating that participants perceiving higher levels of companionate love in their workplace also tended to report stronger organizational culture practices. Engagement was also positively associated with both CL (r = 0.43) and OCP (r = 0.49), reinforcing the idea that these positive constructs co-occur in the work environment. Negative associations were found between Burnout and the other constructs: Burnout correlated strongly and negatively with Engagement (r = −0.62) and moderately with both OCP (r = −0.46) and CL (r = −0.36). The Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to assess discriminant validity, comparing each construct’s AVE with the squared correlations (r²) with other constructs. In all cases, the AVE exceeded the corresponding r², indicating that the constructs measured empirically distinct phenomena.

Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to examine differences in Organizational Culture Practices (OCP), Engagement (ENG), Companionate Love (CL), and Burnout (BURN) scores across sociodemographic groups. Statistically significant differences were found for OCP according to type of organization (H (3) = 24.01, p < .001) and work modality (H (2) = 8.04, p = .018), and for ENG according to educational level (H (3) = 15.09, p = .001) and occupational group (H (11) = 20.18, p = .024). No significant differences were observed in CL or BURN with respect to the sociodemographic variables examined.

Regarding type of organization, self-employed/professional workers presented the highest OCP median scores (Med = 3.92; IQR = 3.04–4.33), followed by the third sector/NGO (Med = 3.75; IQR = 3.50–4.42), the private sector (Med = 3.42; IQR = 2.83–3.98), and the public sector (Med = 3.25; IQR = 2.58–3.67). Dunn’s post hoc tests indicated that public sector participants reported lower OCP scores than those in the private sector (p = .002) and than self-employed/professional workers (p = .003).

For work modality, individuals working remotely reported the highest OCP median (Med = 3.58; IQR = 3.17–4.08), followed by hybrid work (Med = 3.33; IQR = 2.75–3.75) and on-site work (Med = 3.25; IQR = 2.67–3.75). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between on-site and remote work (p = .015), with higher scores in the remote group.

In terms of educational level, engagement was highest among participants with postgraduate education (Med = 5.11; IQR = 4.00–6.00), followed by those with high school (Med = 4.44; IQR = 2.89–5.78), undergraduate education (Med = 4.39; IQR = 3.11–5.78), and primary education (Med = 3.00; IQR = 2.44–4.11). Post hoc tests indicated a significant difference between participants with postgraduate and undergraduate education (p = .024), favoring the former.

Finally, for the occupational group, the highest ENG medians were observed in maintenance/transport/repair (Med = 5.67; single case), security (Med = 5.44; IQR = 4.50–5.89), managers (Med = 5.33; IQR = 4.11–6.00), and education (Med = 5.11; IQR = 4.11–6.00). Post hoc tests revealed a significant difference between managers and supervisors/other occupational areas (p = .049), with managers scoring higher.

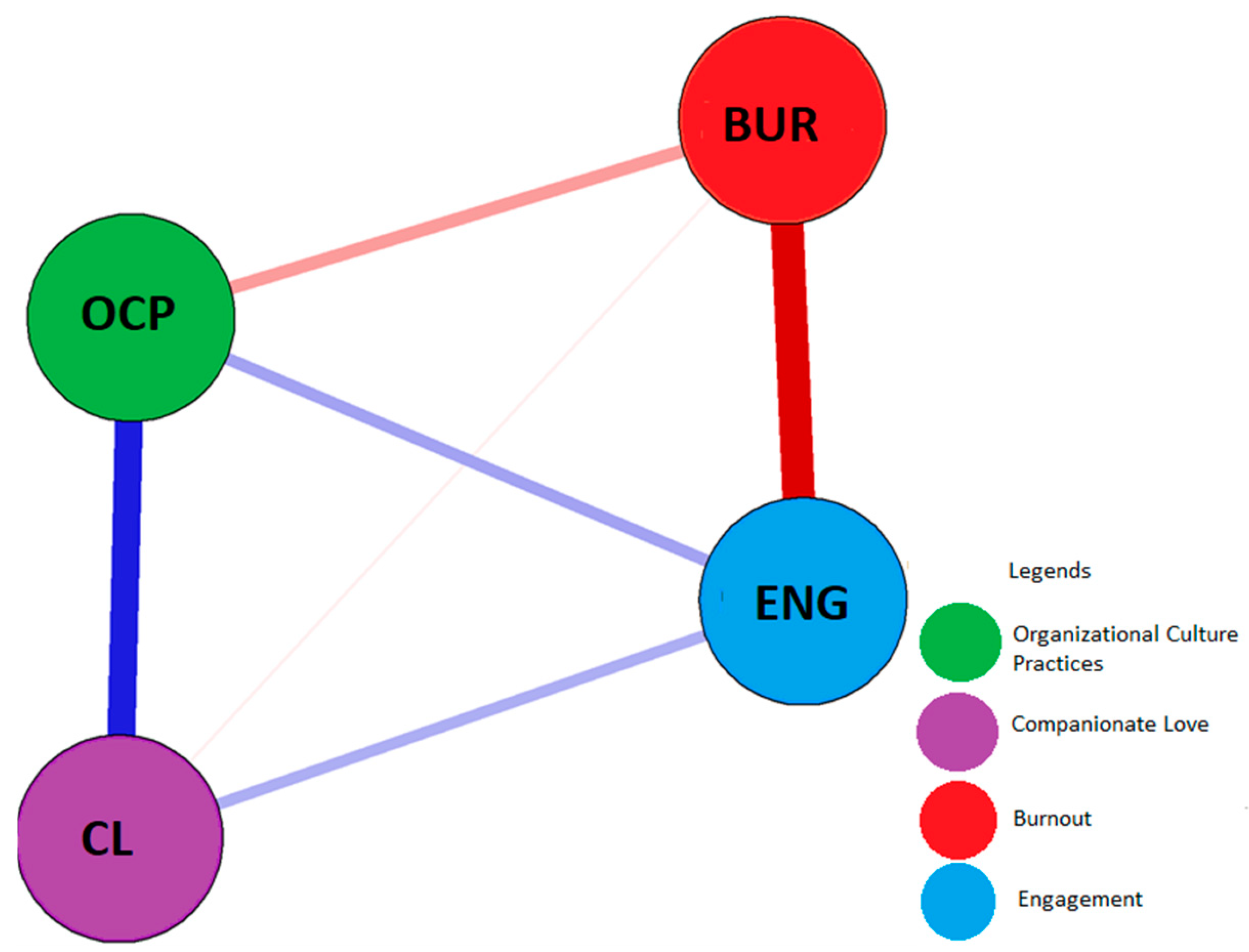

3.3. Network Analysis

The EBIC glasso network estimation revealed the conditional associations among CL, OCP, Engagement, and Burnout—relationships that remain after statistically controlling for the other constructs in the model. The analysis showed that CL, OCP, and Engagement formed a cohesive cluster of positive associations, with the strongest conditional link between OCP and CL (w = 0.42), followed by Engagement with OCP (w = 0.19) and CL with Engagement (w = 0.17). Burnout was negatively associated with both Engagement (w = −0.49) and OCP (w = −0.20), suggesting that higher engagement and stronger organizational culture practices are directly associated with lower burnout levels.

The direct conditional link between CL and Burnout was negligible (w = −0.04), implying that any influence of CL on burnout operates primarily through indirect pathways.

Table 3 details the partial correlation weights (below the diagonal) and the shortest paths (above the diagonal) between constructs.

Table 3 reports the partial correlation weights (below the diagonal) and the shortest paths (above the diagonal). The shortest path metric identifies the most efficient route by which one construct influences another within the network.

3.4. Shortest Path Analysis

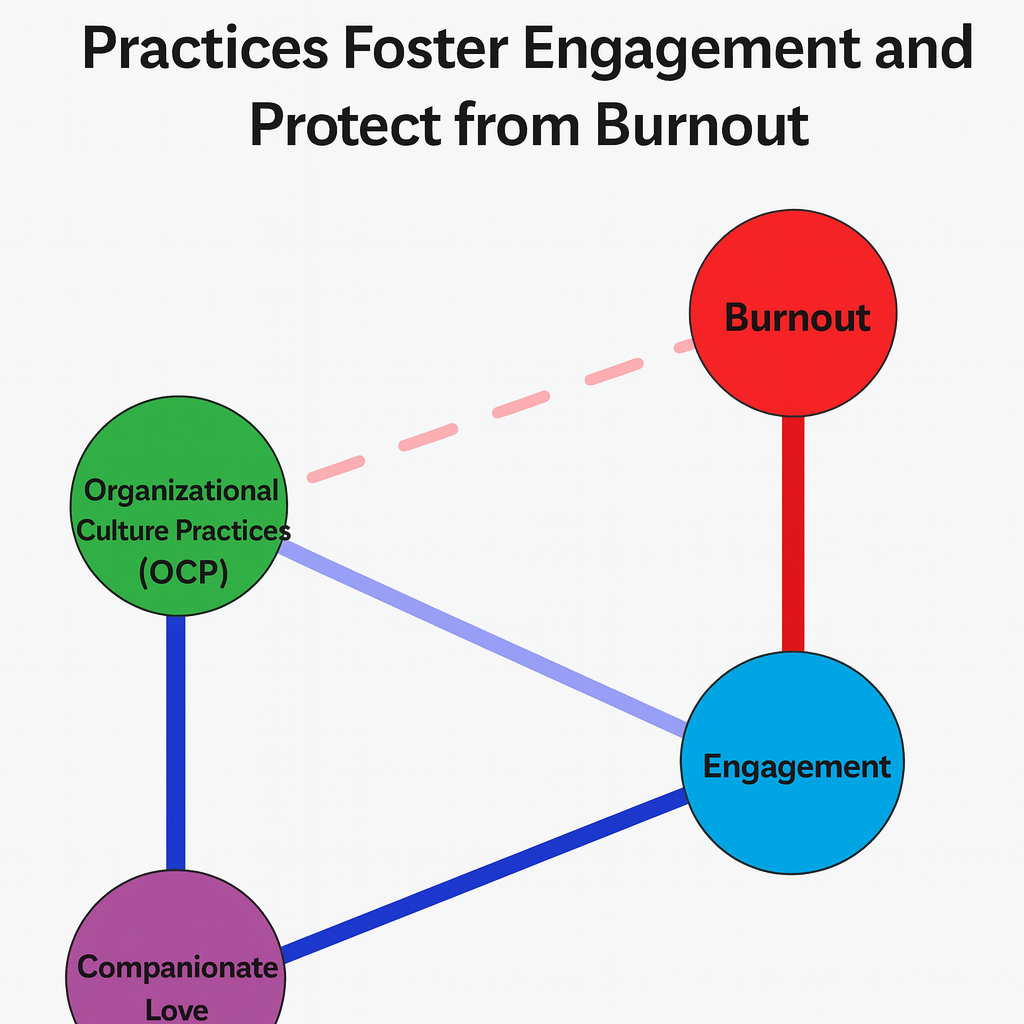

The shortest path analysis, depicted in

Figure 1, identified two main indirect routes linking CL to Burnout. The first pathway is CL → OCP → Burnout, indicating that workplaces with higher levels of companionate love tend to have stronger organizational culture practices, which, in turn, are associated with lower burnout levels. The second pathway is CL → Engagement → Burnout, suggesting that higher companionate love fosters greater engagement, which, in turn, is associated with reduced burnout. These results underscore the mediating role of engagement and organizational culture practices in the relationship between CL and burnout.

3.4. Zero-Order Construct Correlations

For comparative purposes, it presents the zero-order correlations among the four constructs without controlling for other variables. The strongest negative correlation was between Engagement and Burnout (r = −0.62), followed by the negative associations of OCP with Burnout (r = −0.46) and CL with Burnout (r = −0.36). The strongest positive correlation was again between CL and OCP (r = 0.56), with Engagement also showing a moderate positive association with OCP (r = 0.49). This pattern reinforces the findings from both the interconstruct correlations in

Table 2 and the network analysis, highlighting Engagement and OCP as particularly relevant in mitigating burnout.

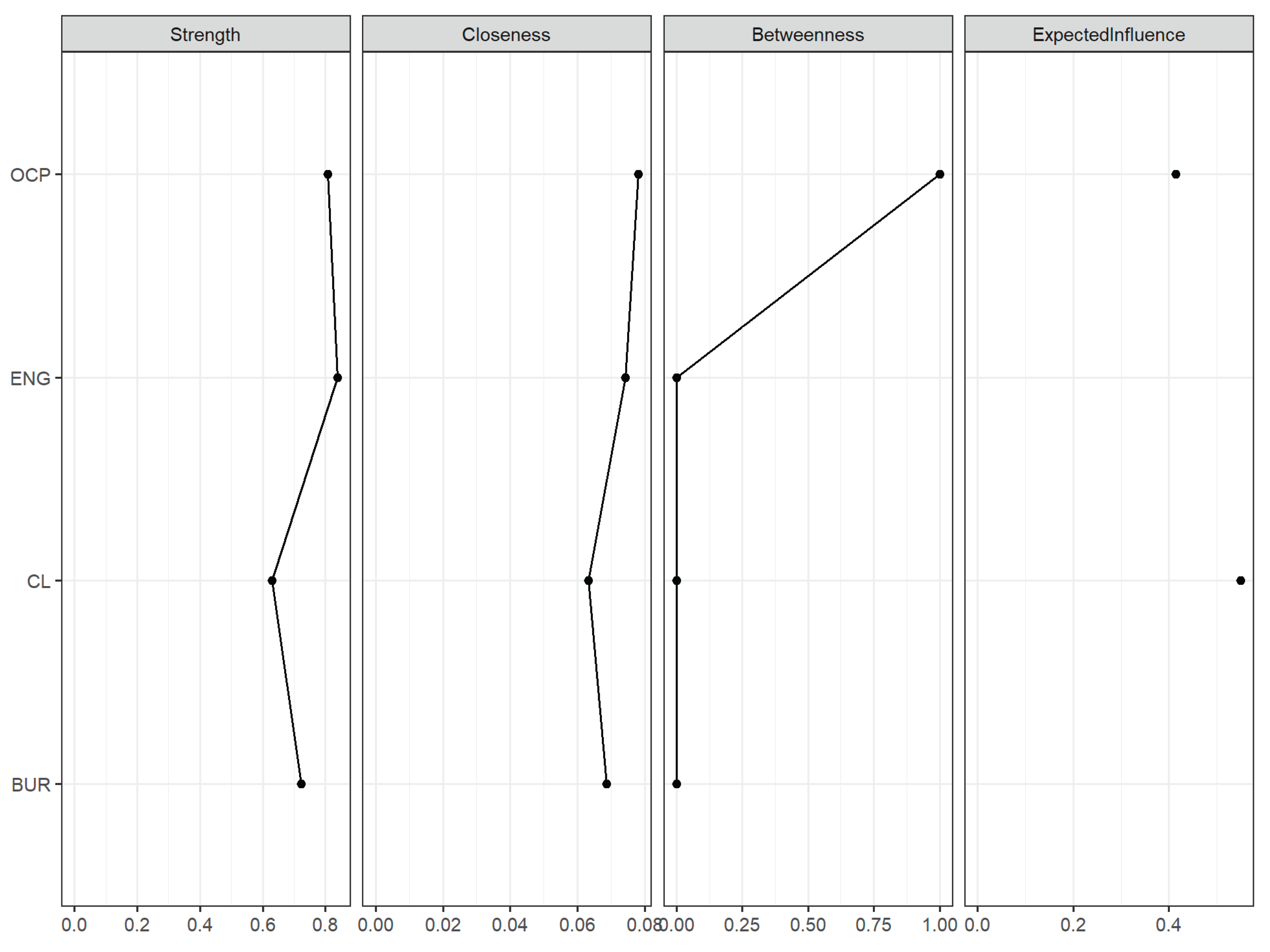

3.5. Centrality Indices

The centrality analysis quantified the relative importance of each construct in the network, using four indices: strength, expected influence, closeness, and betweenness. Stability testing via case-dropping bootstrap indicated good stability for expected influence (CS = 0.75) and acceptable stability for strength (CS = 0.44), but low stability for closeness (CS = 0.13) and betweenness (CS = 0.05). As shown in Figure 8, OCP emerged as the most central construct, with the highest strength and expected influence, indicating its key role in the network. Engagement was the second most central construct, while CL showed moderate centrality, suggesting its influence occurs primarily through OCP and Engagement. Burnout exhibited low closeness and betweenness, functioning more as an outcome influenced by other constructs than as a driver of the network’s dynamics.

Figure 2.

Centrality Indices of the Network Model. Note. Strength = the sum of absolute edge weights connected to a node; Expected Influence = the sum of edge weights (considering the sign); Closeness = the inverse of the sum of shortest path distances to all other nodes; Betweenness = the frequency with which a node lies on the shortest path between two other nodes. OCP = Organizational Culture Practices; ENG = Engagement; CL = Companionate Love; BUR = Burnout.

Figure 2.

Centrality Indices of the Network Model. Note. Strength = the sum of absolute edge weights connected to a node; Expected Influence = the sum of edge weights (considering the sign); Closeness = the inverse of the sum of shortest path distances to all other nodes; Betweenness = the frequency with which a node lies on the shortest path between two other nodes. OCP = Organizational Culture Practices; ENG = Engagement; CL = Companionate Love; BUR = Burnout.

In summary, the findings indicate that companionate love (CL) in the workplace plays a significant role in the dynamics between engagement, organizational culture practices (OCP), and burnout. CL showed a strong positive association with OCP and a moderate association with engagement, suggesting that work environments characterized by greater expressions of affection, care, compassion, and tenderness also tend to foster more humanized organizational practices and higher levels of professional involvement. The relationship between CL and burnout was indirect, operating through strengthening of OCP and increased engagement—both of which served as protective factors against occupational exhaustion. Although some sociodemographic variables displayed statistically significant correlations, their magnitudes were small, indicating that the influence of CL is more strongly explained by relational and cultural aspects of the workplace than by individual characteristics. Overall, this pattern underscores the importance of companionate love as a crucial component in fostering healthier, more supportive work environments.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the relationships among companionate love (CL), organizational culture practices (OCP), work engagement, and burnout among Brazilian workers. The findings revealed a cohesive network of positive associations among CL, OCP, and engagement, and negative associations between these constructs and burnout. These results align with and extend previous research on companionate love, organizational culture, and engagement [

4,

6,

7,

14,

17].

The strongest association observed between CL and OCP indicates that perceptions of emotional warmth in the workplace are closely linked to how employees experience supportive and collaborative organizational dynamics. This finding resonates with Barsade and O’Neill’s demonstration that companionate love fosters team cohesion, resilience, and satisfaction [

4]. It also echoes Itzchakov et al. [

5], whose multi-study investigation confirmed that high-quality listening enhances perceptions of emotional culture, which in turn promotes well-being and cooperation.

Work engagement emerged as a central construct in the network, positively associated with both CL and OCP, and strongly negatively associated with burnout. This supports the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) theory [

13,

14], which posits that job resources—such as emotional support and organizational care—fuel engagement and buffer the effects of job demands. The mediating role of engagement in the relationship between CL and burnout, as revealed by the shortest path analysis, reinforces the motivational pathway proposed by the JD–R model and aligns with Devotto et al. [

15], who identified job crafting and personal resources as key predictors of engagement among Brazilian professionals.

Burnout, in turn, was negatively associated with both OCP and engagement, but showed only a weak direct link with CL. This suggests that the protective effect of emotional culture against burnout operates primarily through its influence on organizational practices and motivational states. Similar patterns were observed by Dreison et al. [

2], who found that supervisor autonomy support and team cohesion were associated with lower burnout, even when job demands remained high. Likewise, O’Neill et al. [

6] demonstrated that a culture of companionate love acts as an antidote to emotional exhaustion and absenteeism, particularly in high-stress environments.

The centrality analysis further highlighted OCP as the most influential construct in the network, underscoring the pivotal role of organizational practices in shaping emotional climates and psychological outcomes. This finding is particularly relevant in the Brazilian context, where public sector organizations often exhibit bureaucratic and hierarchical cultures that hinder innovation and emotional expression [

9,

12]. The positive association between remote work and higher OCP scores suggests that flexible modalities may facilitate more inclusive and emotionally intelligent practices, a hypothesis that warrants further investigation.

Educational level and occupational groups were also associated with engagement, with higher scores among postgraduate professionals and managers. These results align with Böttcher and Monteiro [

20], who found that personal resources such as hope and career identity significantly predicted engagement in managerial roles. The absence of strong associations between sociodemographic variables and CL or burnout reinforces the idea that emotional and cultural factors in the workplace transcend individual characteristics, as suggested by Farina et al. [

18] and Costa [

19].

Taken together, these findings contribute to a growing body of evidence that emotional culture and organizational practices are not peripheral elements but central drivers of employee well-being. They highlight the importance of fostering companionate love and implementing culturally attuned practices to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Future research should explore longitudinal designs and multi-level models to capture the dynamic interplay among these constructs over time and across organizational contexts.

The group comparison analyses revealed meaningful differences in perceptions of organizational culture practices (OCP) and work engagement across organizational types, work modalities, educational levels, and occupational groups. Participants in the public sector reported significantly lower OCP scores than those in the private sector and self-employed professionals. This finding aligns with the observations of OECD [

12] and Potye and Moscon [

9], who describe Brazilian public organizations as bureaucratic, hierarchical, and resistant to innovation—traits that may hinder the development of emotionally intelligent and humanized practices.

Interestingly, our data show that remote workers reported the highest OCP scores, followed by hybrid and on-site workers. This suggests that remote work may facilitate perceptions of organizational care, flexibility, and emotional support. These results echo findings from Itzchakov et al. [

5], who emphasize the role of high-quality listening and emotional communication in cultivating companionate love and organizational trust, which may be more easily fostered in remote settings where intentional communication is required.

Educational level was positively associated with engagement and negatively with burnout, with postgraduate participants reporting the highest engagement scores. This pattern is consistent with Böttcher and Monteiro [

20], who found that personal resources such as hope, career identity, and self-efficacy are stronger among highly educated professionals and contribute to higher engagement. The protective role of education may reflect greater access to autonomy, meaningful work, and coping strategies, as suggested by Bakker and de Vries [

3].

Occupational groups also influenced engagement, with managers and educators reporting higher scores than other categories. This supports the notion that leadership roles and educational environments may offer more opportunities for job crafting and resource mobilization, as discussed by Devotto et al. [

15] and Souza [

16]. The presence of meaningful tasks, decision-making autonomy, and professional development may enhance engagement and buffer against burnout.

The network analysis further showed the structural dynamics among the constructs. Companionate love (CL), OCP, and engagement formed a tightly connected cluster, while burnout remained peripheral, influenced primarily by engagement and OCP. The shortest path analysis confirmed that CL influences burnout indirectly through OCP and engagement, reinforcing the mediating role of these constructs. This finding aligns with O’Neill et al. [

6], who demonstrated that companionate love serves as an antidote to emotional exhaustion and absenteeism, particularly when embedded in supportive organizational cultures.

Centrality indices identified OCP as the most influential node in the network, followed by engagement. This suggests that organizational practices—such as intersectoral communication, mental health promotion, and humanized leadership—are pivotal in shaping emotional climates and motivational states. The low centrality of burnout indicates that it functions more as an outcome than a driver, influenced by the presence or absence of emotional and cultural resources.

These findings underscore the importance of integrating emotional culture and organizational practices into workplace interventions. Rather than focusing solely on individual coping strategies, organizations should invest in systemic changes that promote companionate love, inclusive communication, and leadership development. As Dreison et al. [

2] and Schaufeli [

22] argue, enhancing job resources may be a more feasible and effective strategy than reducing demands—especially in high-pressure environments.

In sum, the study contributes to a growing body of evidence that emotional and cultural factors are central to work well-being. By demonstrating the interconnectedness of CL, OCP, engagement, and burnout, this framework offers a comprehensive understanding of and a means to improve the psychological health of Brazilian workers. Future research should explore longitudinal designs, cross-cultural comparisons, and intervention studies to validate further and expand these findings.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study offer meaningful contributions to both organizational theory and practice, particularly to promoting psychological well-being in the workplace. The strong associations between companionate love, organizational culture practices (OCP), and work engagement suggest that emotional and cultural factors are not peripheral but central to the health of organizational systems. Organizations seeking to reduce burnout and foster sustainable engagement should consider implementing strategies that cultivate emotional culture—especially expressions of affection, compassion, and tenderness—as well as structural practices that promote communication, institutional care, and humanized leadership. Training programs focused on high-quality listening and relational intelligence, as proposed by Itzchakov et al. [

5], may serve as practical tools for embedding companionate love into organizational routines. Moreover, the centrality of OCP in the network analysis underscores the importance of organizational-level interventions. Rather than relying solely on individual coping mechanisms, organizations should invest in systemic changes that enhance cultural coherence and psychological safety. Engagement, identified as a key mediator between emotional culture and burnout, can be strengthened through job crafting opportunities, autonomy, and meaningful work—elements that align with the motivational pathway of the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) theory [

13,

14]. These insights are particularly relevant for public sector institutions, which, as highlighted by OECD [

12] and Potye and Moscon [

9], often struggle with bureaucratic rigidity and hierarchical cultures that inhibit innovation and emotional expression. Tailoring interventions to specific organizational contexts, including remote and hybrid work modalities, may further enhance their effectiveness.

Despite its contributions, the study is not without limitations. First, the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to draw causal inferences. While network modeling provides a sophisticated view of structural relationships, longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the temporal dynamics and directionality among constructs. Second, the reliance on self-report measures introduces potential biases, including social desirability and standard method variance. Although validated instruments were employed, future research could benefit from multi-source data, such as peer evaluations and behavioral metrics. Third, the sample composition—predominantly highly educated professionals from the public sector—may limit the generalizability of findings to other occupational groups, such as industrial workers or those in informal sectors. Fourth, the study was conducted within the Brazilian cultural context, where emotional expression and organizational norms may differ from those in other countries. Cross-cultural comparisons would help assess the universality of the observed patterns. Finally, the Organizational Culture Practices (OCP) scale was developed specifically for this study. While it demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties, further validation is required to establish its reliability and applicability across diverse organizational settings.

Taken together, these limitations suggest avenues for future research and underscore the importance of continued exploration into the emotional and cultural foundations of workplace well-being. By integrating companionate love, organizational practices, and engagement into a unified framework, this study contributes to a more holistic understanding of how organizations can cultivate environments that are not only productive but also psychologically sustainable.

This study provides compelling evidence that emotional and cultural dimensions of the workplace—specifically companionate love and organizational culture practices (OCP)—play a critical role in shaping employee engagement and mitigating burnout. Through a robust network analysis, we demonstrated that companionate love is strongly associated with perceptions of humanized organizational practices and indirectly contributes to lower burnout levels by increasing engagement and strengthening cultural support. These findings reinforce the theoretical propositions of the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) model [

13,

14], highlighting the importance of both emotional and structural resources in promoting occupational well-being.

The centrality of OCP in the network underscores its strategic relevance for organizational interventions. Practices such as intersectoral communication, mental health promotion, and humanized leadership not only enhance engagement but also serve as buffers against emotional exhaustion. Engagement, in turn, emerged as a key motivational construct, mediating the relationship between emotional culture and burnout and reflecting the dynamic interplay between individual and contextual factors.

Significantly, the study expands the findings by integrating constructs that are often examined in isolation—companionate love, engagement, burnout, and organizational culture—into an analytical framework. It also contributes to the Brazilian organizational psychology field by offering empirical insights grounded in a diverse national sample. The findings suggest that fostering emotionally intelligent and culturally responsive workplaces is not merely a matter of ethics or employee satisfaction, but a strategic imperative for organizational sustainability.

In sum, this study affirms that love, care, and cultural coherence are not peripheral to organizational life—they are foundational. By embracing emotional culture and investing in supportive practices, organizations can cultivate environments that are not only productive but also psychologically sustainable and human-centered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa and Ana Cláudia Souza Vazquez; methodology, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa and Ana Cláudia Souza Vazquez; software, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa (data analysis conducted in RStudio); validation, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa, Ana Cláudia Souza Vazquez, and Claudio Simon Hutz; formal analysis, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa; investigation, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa; resources, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa; data curation, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa; writing—original draft preparation, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa; writing—review and editing, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa, Ana Cláudia Souza Vazquez, and Claudio Simon Hutz; visualization, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa; supervision, Ana Cláudia Souza Vazquez and Claudio Simon Hutz; project administration, Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the doctoral thesis of Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa at the Graduate Program in Psychology of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) and was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil — Finance Code 001. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Brazil (protocol code CAAE 64195322.0.0000.5334; date of approval: April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents provided electronic consent prior to completing the survey. No identifiable personal data was collected.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and confidentiality restrictions involving human participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Graduate Program in Psychology at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) for its institutional and academic support throughout the development of this study. This research was conducted as part of the doctoral thesis of Joice Franciele Friedrich Almansa. It was supported by a doctoral scholarship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil. Special thanks are extended to all participants who generously contributed their time and experiences, and to colleagues from the research group for their valuable collaboration during data collection and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil, had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAPES |

Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior |

| CL |

Companionate Love |

| OCP |

Organizational Culture Practices |

| ENG |

Work Engagement |

| BURN |

Burnout |

| JD–R |

Job Demands–Resources Model |

| ECET |

Emotional Culture at Work Scale |

| UWES |

Utrecht Work Engagement Scale |

| BAT |

Burnout Assessment Tool |

| UFRGS |

Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul |

References

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Desart, S.; De Witte, H. Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Development, validity, and reliability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(24), 9495. [CrossRef]

-

Dreison, K.C.; Luther, L.; Bonfils, K.A.; Sliter, M.T.; McGrew, J.H.; Salyers, M.P. Integrating self-determination and job demands–resources theory in predicting mental health provider burnout. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 2018, 45(1), 121–130. [CrossRef]

-

Bakker, A.B.; de Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 2021, 34(1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

-

Barsade, S.G.; O’Neill, O.A. What’s love got to do with it? A longitudinal study of the culture of companionate love and employee and client outcomes in a long-term care setting. Administrative Science Quarterly 2014, 59(4), 551–598. [CrossRef]

-

Itzchakov, G.; O’Neill, O.A.; Van Quaquebeke, N. Sowing the seeds of love: Cultivating perceptions of culture of companionate love through listening and its effects on organizational outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2025, 46(1), 1–23. [CrossRef]

-

O’Neill, O.A.; Rothbard, N.P. The psychological and financial impacts of an emotional culture of anxiety and its antidote, an emotional culture of companionate love. Academy of Management Journal 2023, 66(2), 345–372. [CrossRef]

- Belkin, L. Y. , & Kong, D. T. Supervisor companionate love expression and elicited subordinate gratitude as moral-emotional facilitators of voice amid COVID-19. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2021, 17(6), 832–846. [CrossRef]

-

Aguiar, A.R.C.; Silva, M.R.; Oliveira, M.A. Cultura organizacional e adoecimento no trabalho: Uma revisão sobre as relações entre cultura, burnout e estresse ocupacional. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho 2017, 17(1), 91–99. [CrossRef]

-

Potye, M.C.; Moscon, D. A influência da cultura organizacional e do estilo de liderança no desenvolvimento de práticas gerenciais. Revista Gestão & Desenvolvimento 2022, 19(1), 45–60. [CrossRef]

-

Spier, H.S.; Silva, C.E.L. Innovation policies in Brazilian public universities. Innovation & Management Review 2025, 22(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

-

Koerich, A.B.; Mussi, C.C.; de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.; Casagrande, J.L. Critical factors in the implementation of innovation: A case study of a Brazilian public organization. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 2025, 91(4), e70018. [CrossRef]

-

OECD.Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions in Brazil; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [CrossRef]

-

Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job Demands–Resources theory and the role of individual cognitive and behavioral strategies. In The Fun and Frustration of Modern Working Life: Contributions from an Occupational Health Psychology Perspective; Taris, T., Peeters, M., De Witte, H., Eds.; Pelckmans Pro: Antwerp, Belgium, 2019; pp. 94–104. https://www.isonderhouden.nl/doc/pdf/arnoldbakker/articles/articles_arnold_bakker_500.pdf.

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2023, 10, 25–53. [CrossRef]

-

Devotto, F.; Vazquez, A.C.S.; Souza, G.H.S. Work engagement and job crafting of Brazilian professionals. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho 2020, 20(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

-

Souza, G.H.S. Engajamento no trabalho. In Psicologia Positiva Aplicada ao Trabalho; Vazquez, A.C.S., Ed.; Vetor Editora: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017; pp. 89–106.

-

Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two-sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 2002, 3(1), 71–92. [CrossRef]

-

Farina, L.S.A.; Rodrigues, G.R.; Hutz, C.S. Flow and engagement at work: A literature review. Psico-USF 2018, 23(4), 633–642. [CrossRef]

-

Costa, M.C. Engajamento no trabalho: Estudo bibliométrico da produção científica nacional nas plataformas CAPES e SPELL (2010–2019). Revista de Administração Contemporânea 2021, 25(3), 1–15. [CrossRef]

-

Böttcher, L.; Monteiro, J.K. Engajamento no trabalho em gestores: Influência de recursos pessoais e do trabalho. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho 2021, 21(2), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, A.C.S.; Magnan, E.D.S.; Pacico, J.C.; Hutz, C.S.; Schaufeli, W.B. Adaptation and validation of the Brazilian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Psico-USF 2015, 20, 207–217. [CrossRef]

-

Schaufeli, W.B. Applying the Job Demands–Resources model: A ‘how to’ guide to developing interventions to reduce burnout and increase engagement. Organizational Dynamics 2017, 46(2), 120–132. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).