Submitted:

04 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

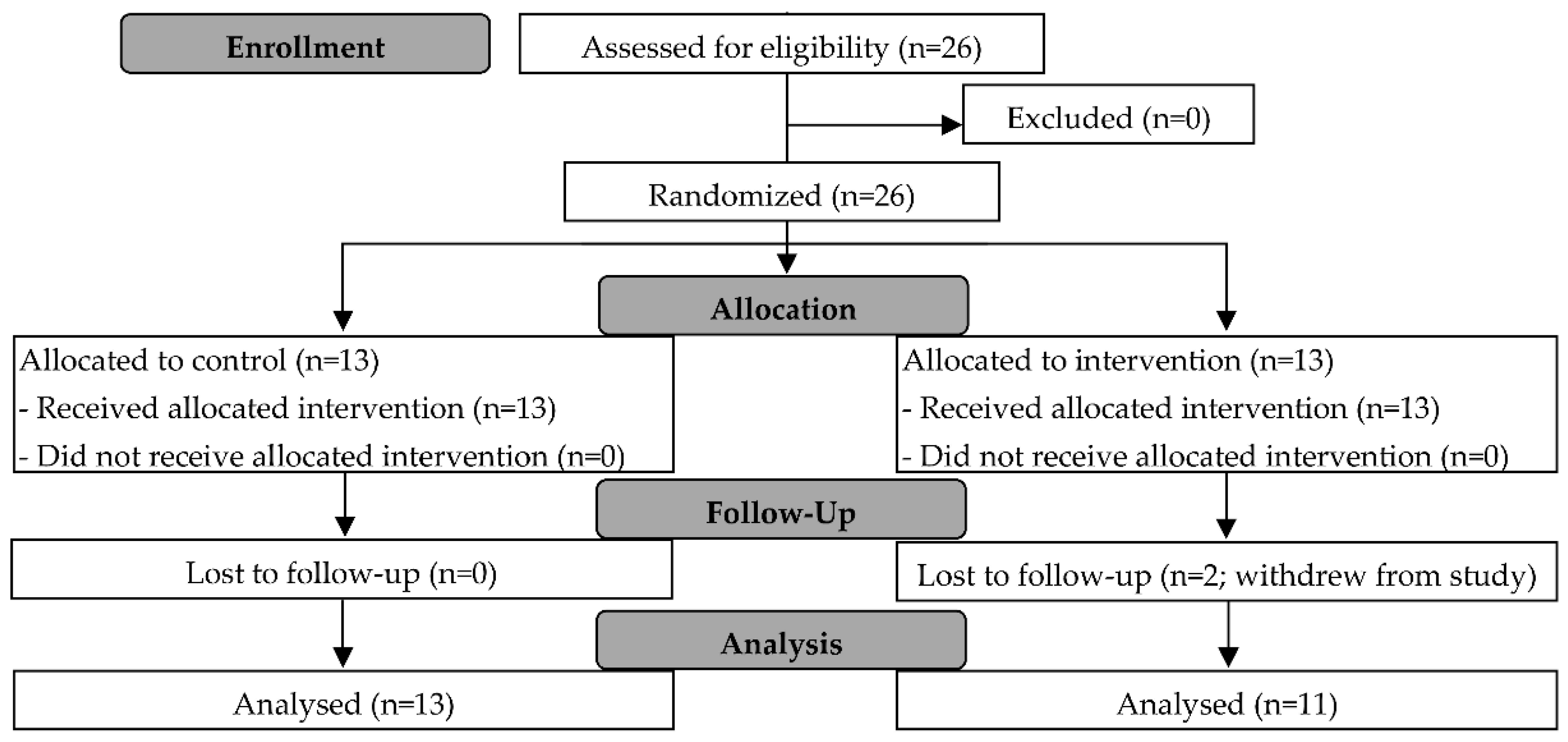

2.1. Study 1 Design

2.1.1. Participant Screening

2.1.2. ADF Protocol

2.1.3. Laboratory Sessions

2.1.4. Body Composition

2.1.5. Anthropometry

2.1.6. Health Assessments

2.1.7. Physical Activity Questionnaire and Dietary Record

2.2. Study 2 Design

2.2.1. ADF Protocol

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

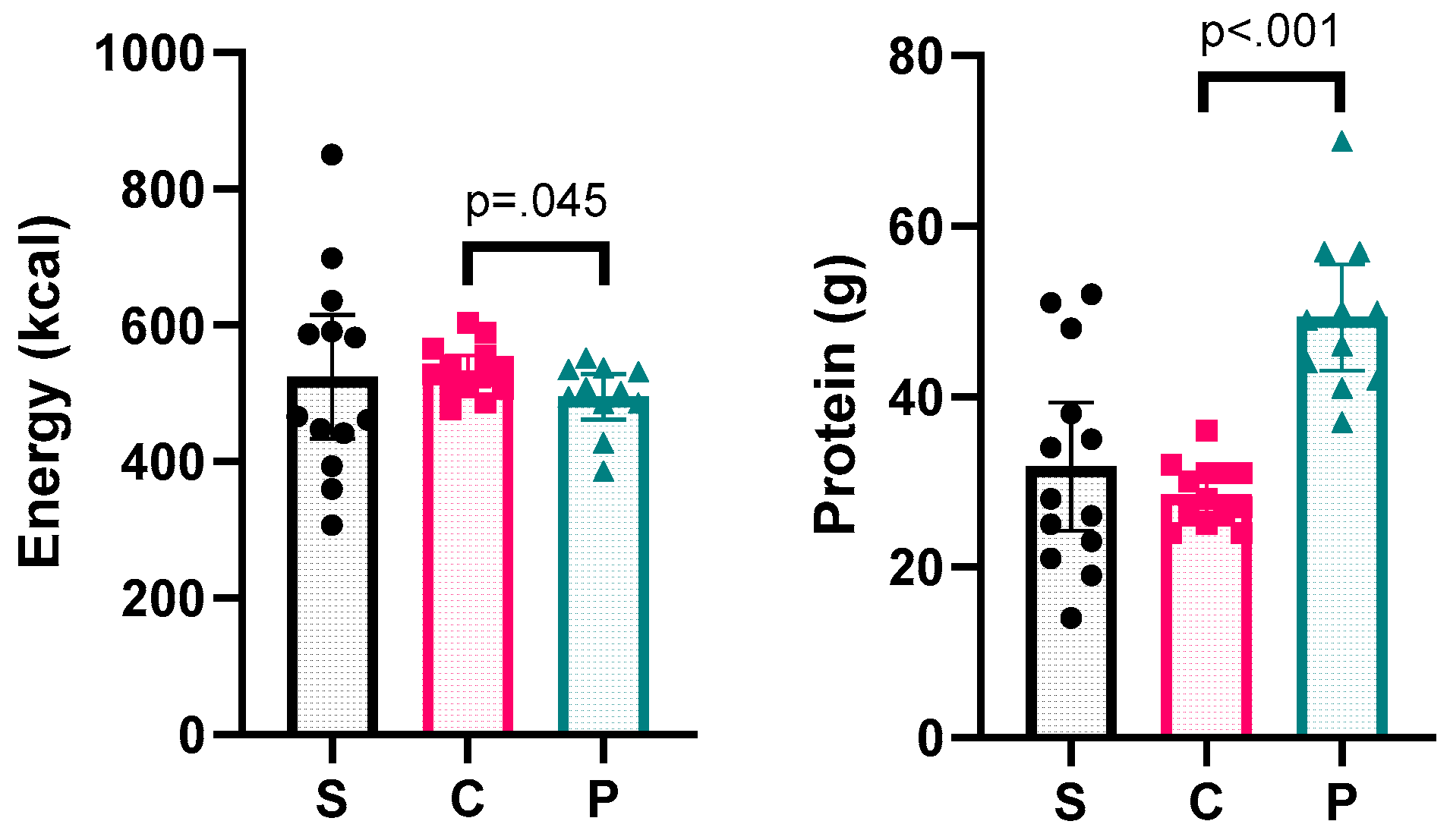

3.2. Fasting Day Meal

3.3. Hydration Status

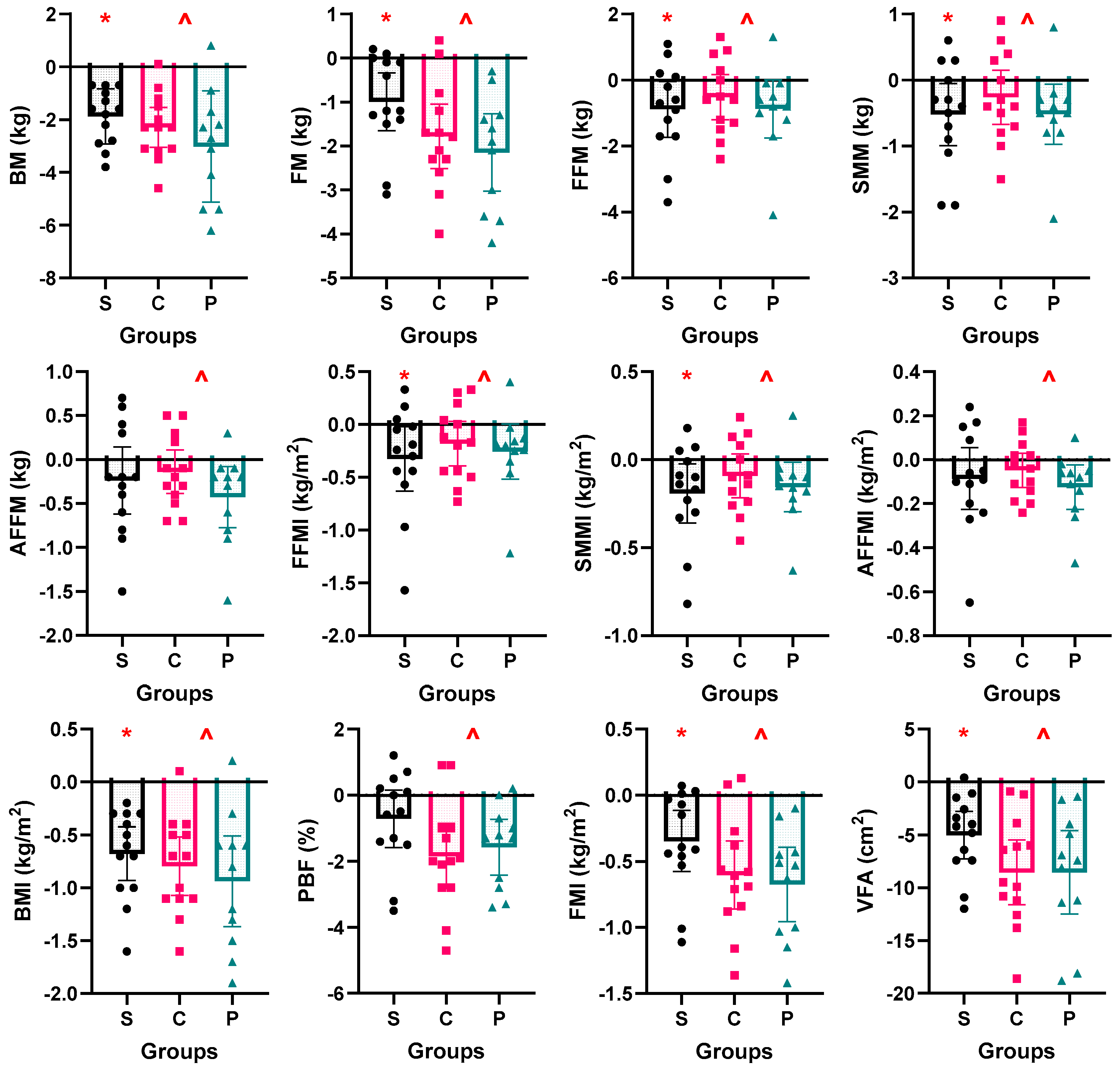

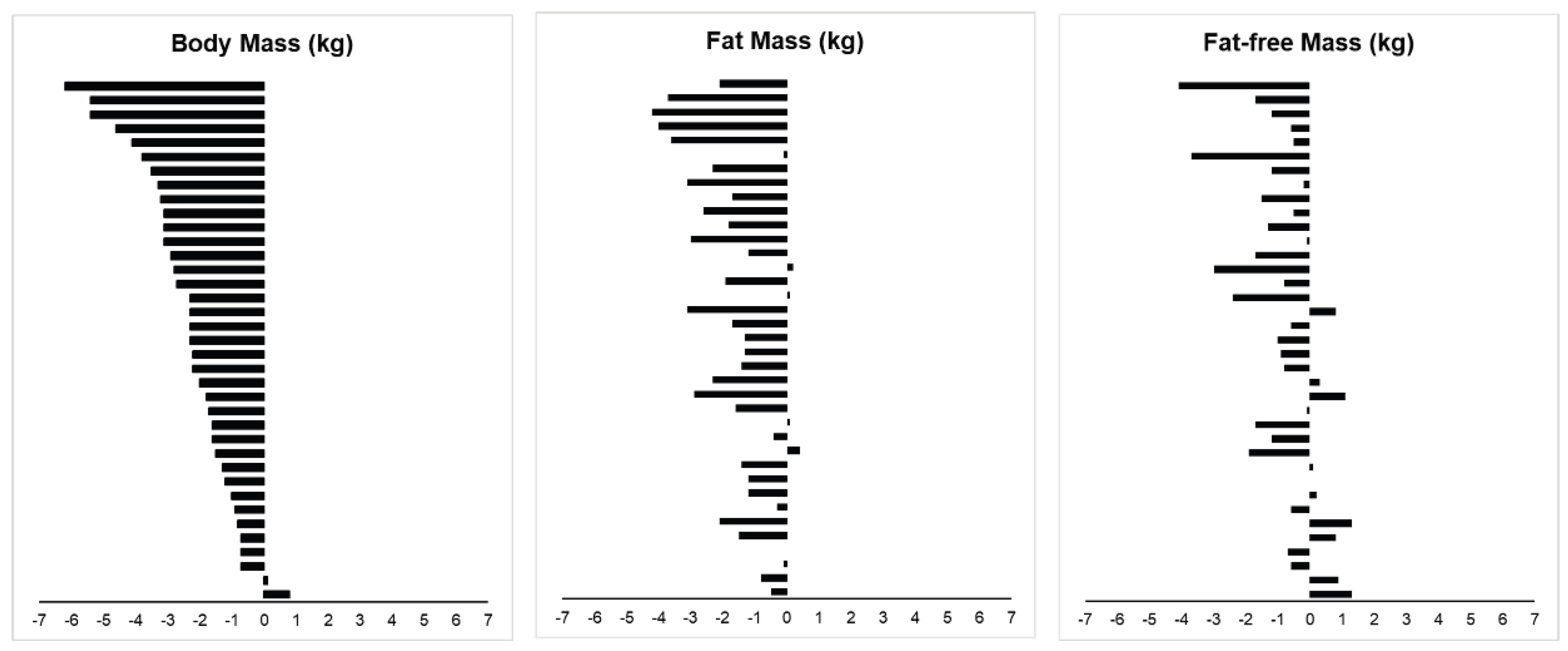

3.4. Body Composition

3.5. Physical Activity and Blood Markers

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Short-Term ADF on Body Composition

4.2. Effectiveness of Protein Supplementation During Fasting Day

4.3. Potential Influence of Physical Activity Type on Muscle Mass Preservation

4.4. Effectiveness of Short-Term ADF on Blood Health Indices

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADF | Alternate-day fasting |

| AFFM | Appendicular fat-free mass |

| AFFMI | Appendicular fat-free mass index |

| BIA | Bioelectrical impedance analysis |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| C | Control group |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| FFM | Fat-free mass |

| FFMI | Fat-free mass index |

| FG | Fasting blood glucose |

| FM | Fat mass |

| FMI | Fat mass index |

| GEE | Generalized estimating equation |

| GPAQ | Global physical activity questionnaire |

| ICW/ECW | Intracellular water/extracellular water |

| IF | Intermittent fasting |

| IRB | Institutional review board |

| MET | Metabolic Equivalent of Task |

| MPS | Muscle protein synthesis |

| NTU | Nanyang technological university |

| P | Protein group |

| PBF | Percentage body fat |

| rANOVA | repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) |

| RCT | Randomized-controlled trial |

| S | Single-arm study |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SMM | Skeletal muscle mass |

| SMMI | Skeletal muscle mass index |

| VFA | Visceral fat area |

| VLCD | Very low calorie dieting |

References

- WHO. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data – Overweight and obesity 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight_obesity/obesity_adults/en/ (accessed on 30 Aug 2024).

- WHO. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.K.; Wee, S.-L.; Pang, B.; Lau, L.K.; Jabbar, K.A.; Seah, W.T.; Ng, T.P. Relationship between BMI with percentage body fat and obesity in Singaporean adults – The Yishun Study. BMC Public Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; McPherson, K.; Marsh, T.; Gortmaker, S.L.; Brown, M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011, 378, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Zhu, L.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; H, O.S.; Tinsley, G.M.; Fu, P. Effects of intermittent fasting and energy-restricted diets on lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. 2020, 77, 110801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Hong, N.; Kim, K.W.; Cho, S.J.; Lee, M.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Kang, E.S.; Cha, B.S.; Lee, B.W. The Effectiveness of Intermittent Fasting to Reduce Body Mass Index and Glucose Metabolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welton, S.; Minty, R.; O'Driscoll, T.; Willms, H.; Poirier, D.; Madden, S.; Kelly, L. Intermittent fasting and weight loss: Systematic review. Can. Fam. Physician 2020, 66, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patterson, R.E.; Sears, D.D. Metabolic Effects of Intermittent Fasting. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varady, K.A.; Bhutani, S.; Klempel, M.C.; Kroeger, C.M.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Haus, J.M.; Hoddy, K.K.; Calvo, Y. Alternate day fasting for weight loss in normal weight and overweight subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Seo, Y.G.; Paek, Y.J.; Song, H.J.; Park, K.H.; Noh, H.M. Effect of alternate-day fasting on obesity and cardiometabolic risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metab. 2020, 111, 154336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cai, T.; Zhou, Z.; Mu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y. Health Effects of Alternate-Day Fasting in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 586036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamdan, B.A.; Garcia-Alvarez, A.; Alzahrnai, A.H.; Karanxha, J.; Stretchberry, D.R.; Contrera, K.J.; Utria, A.F.; Cheskin, L.J. Alternate-day versus daily energy restriction diets: which is more effective for weight loss? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2016, 2, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Kroeger, C.M.; Barnosky, A.; Klempel, M.C.; Bhutani, S.; Hoddy, K.K.; Gabel, K.; Freels, S.; Rigdon, J.; Rood, J.; et al. Effect of Alternate-Day Fasting on Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Cardioprotection Among Metabolically Healthy Obese Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekovic, S.; Hofer, S.J.; Tripolt, N.; Aon, M.A.; Royer, P.; Pein, L.; Stadler, J.T.; Pendl, T.; Prietl, B.; Url, J.; et al. Alternate Day Fasting Improves Physiological and Molecular Markers of Aging in Healthy, Non-obese Humans. Cell. Metab. 2019, 30, 462–476.e466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronn, L.K.; Smith, S.R.; Martin, C.K.; Anton, S.D.; Ravussin, E. Alternate-day fasting in nonobese subjects: effects on body weight, body composition, and energy metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halberg, N.; Henriksen, M.; Soderhamn, N.; Stallknecht, B.; Ploug, T.; Schjerling, P.; Dela, F. Effect of intermittent fasting and refeeding on insulin action in healthy men. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) 2005, 99, 2128–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klempel, M.C.; Bhutani, S.; Fitzgibbon, M.; Freels, S.; Varady, K.A. Dietary and physical activity adaptations to alternate day modified fasting: implications for optimal weight loss. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 35–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeman, I.; Smith, H.A.; Chowdhury, E.; Chen, Y.C.; Carroll, H.; Johnson-Bonson, D.; Hengist, A.; Smith, R.; Creighton, J.; Clayton, D.; et al. A randomized controlled trial to isolate the effects of fasting and energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic health in lean adults. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varady, K.A.; Bhutani, S.; Church, E.C.; Klempel, M.C. Short-term modified alternate-day fasting: a novel dietary strategy for weight loss and cardioprotection in obese adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2009, 90, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derron, N.; Güntner, A.T.; Weber, I.C.; Braun, J.; Koska, İ.Ö.; Othman, A.; Mönch, L.; von Eckardstein, A.; Puhan, M.A.; Beuschlein, F.; et al. Alternate-day fasting elicits larger changes in fat mass than time-restricted eating in adults without obesity – A randomized clinical trial. Clinical Nutrition 2025, 53, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, A.A.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Wildman, R.; Kleiner, S.; VanDusseldorp, T.; Taylor, L.; Earnest, C.P.; Arciero, P.J.; Wilborn, C.; Kalman, D.S.; et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: diets and body composition. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2017, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Lemmens, S.G.; Westerterp, K.R. Dietary protein - its role in satiety, energetics, weight loss and health. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108 Suppl 2, S105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wycherley, T.P.; Moran, L.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Noakes, M.; Brinkworth, G.D. Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012, 96, 1281–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenen, S.; Bonomi, A.G.; Lemmens, S.G.; Scholte, J.; Thijssen, M.A.; van Berkum, F.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Relatively high-protein or 'low-carb' energy-restricted diets for body weight loss and body weight maintenance? Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backx, E.M.P.; Tieland, M.; Borgonjen-van den Berg, K.J.; Claessen, P.R.; van Loon, L.J.C.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M. Protein intake and lean body mass preservation during energy intake restriction in overweight older adults. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutani, S.; Klempel, M.C.; Kroeger, C.M.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Varady, K.A. Alternate day fasting and endurance exercise combine to reduce body weight and favorably alter plasma lipids in obese humans. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2013, 21, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, S.L.; Faria, O.P.; Cardeal, M.D.; Ito, M.K. Validation study of multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry among obese patients. Obes. Surg. 2014, 24, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Tordecilla-Sanders, A.; Correa-Bautista, J.E.; González-Ruíz, K.; González-Jiménez, E.; Triana-Reina, H.R.; García-Hermoso, A.; Schmidt-RioValle, J. Validation of multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis versus dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry to measure body fat percentage in overweight/obese Colombian adults. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosy-Westphal, A.; Later, W.; Hitze, B.; Sato, T.; Kossel, E.; Gluer, C.C.; Heller, M.; Muller, M.J. Accuracy of bioelectrical impedance consumer devices for measurement of body composition in comparison to whole body magnetic resonance imaging and dual X-ray absorptiometry. Obes. Facts 2008, 1, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutani, S.; Klempel, M.C.; Berger, R.A.; Varady, K.A. Improvements in coronary heart disease risk indicators by alternate-day fasting involve adipose tissue modulations. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2010, 18, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, T.; Bull, F. Development of the World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). J. Public Health 2006, 14, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification, E., and Treatment of Obesity in Adults (US). Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2003/ (accessed on 2 Feb 2024).

- Volek, J.S.; Vanheest, J.L.; Forsythe, C.E. Diet and exercise for weight loss: a review of current issues. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.S.; Clarke, R.E.; Coulter, S.N.; Rounsefell, K.N.; Walker, R.E.; Rauch, C.E.; Huggins, C.E.; Ryan, L. Intermittent energy restriction and weight loss: a systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, E.; Yeat, N.C.; Mittendorfer, B. Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, A.E.; Bibby, B.M.; Hansen, M. Effect of a Whey Protein Supplement on Preservation of Fat Free Mass in Overweight and Obese Individuals on an Energy Restricted Very Low Caloric Diet. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.R.; Miller, S.L. The Recommended Dietary Allowance of Protein: A Misunderstood Concept. JAMA 2008, 299, 2891–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchward-Venne, T.A.; Breen, L.; Di Donato, D.M.; Hector, A.J.; Mitchell, C.J.; Moore, D.R.; Stellingwerff, T.; Breuille, D.; Offord, E.A.; Baker, S.K.; et al. Leucine supplementation of a low-protein mixed macronutrient beverage enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis in young men: a double-blind, randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, M.C.; McGlory, C.; Bolster, D.R.; Kamil, A.; Rahn, M.; Harkness, L.; Baker, S.K.; Phillips, S.M. Leucine, Not Total Protein, Content of a Supplement Is the Primary Determinant of Muscle Protein Anabolic Responses in Healthy Older Women. The Journal of nutrition 2018, 148, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigle, D.S.; Breen, P.A.; Matthys, C.C.; Callahan, H.S.; Meeuws, K.E.; Burden, V.R.; Purnell, J.Q. A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005, 82, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Breen, L.; Burd, N.A.; Hector, A.J.; Churchward-Venne, T.A.; Josse, A.R.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Phillips, S.M. Resistance exercise enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis with graded intakes of whey protein in older men. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frimel, T.N.; Sinacore, D.R.; Villareal, D.T. Exercise attenuates the weight-loss-induced reduction in muscle mass in frail obese older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | S (n=13) | C (n=13) | P (n=11) | All (n=37) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (y) | Pre | 26 | 4 | 24 | 2 | 26 | 1 | 25 | 3 |

| Post | 26 | 4 | 24 | 2 | 26 | 1 | 25 | 3 | |

| Height (m) | Pre | 1.72 | 0.07 | 1.72 | 0.04 | 1.78 | 0.07 | 1.74 | 0.07 |

| Post | 1.72 | 0.07 | 1.72 | 0.03 | 1.78 | 0.07 | 1.74 | 0.06 | |

| Body Mass (kg) | Pre | 80.1 | 12.8 | 74.5 | 7.8 | 89.4 | 18.8 | 80.9 | 14.5 |

| Post | 78.2 | 12.5 | 72.2 | 8.2 | 86.4 | 17.6 | 78.5 | 14.0 | |

| Fat Mass (kg) | Pre | 19.8 | 7.6 | 16.4 | 5.9 | 23.4 | 12.2 | 19.7 | 9.0 |

| Post | 18.8 | 7.6 | 14.6 | 6.2 | 21.3 | 12.0 | 18.1 | 8.9 | |

| FFM (kg) | Pre | 60.3 | 7.2 | 58.1 | 4.8 | 66.0 | 8.7 | 61.2 | 7.5 |

| Post | 59.4 | 6.7 | 57.6 | 5.2 | 65.1 | 8.0 | 60.5 | 7.2 | |

| SMM (kg) | Pre | 34.2 | 4.2 | 32.8 | 2.9 | 37.4 | 5.1 | 34.6 | 4.4 |

| Post | 33.6 | 4.0 | 32.6 | 3.2 | 36.8 | 4.7 | 34.2 | 4.3 | |

| AFFM (kg) | Pre | 24.9 | 3.2 | 24.1 | 2.2 | 28.1 | 4.5 | 25.6 | 3.7 |

| Post | 24.7 | 3.0 | 23.9 | 2.3 | 27.7 | 4.2 | 25.3 | 3.5 | |

| FFMI (kg/m2) | Pre | 20.4 | 1.8 | 19.6 | 1.3 | 20.7 | 1.9 | 20.2 | 1.7 |

| Post | 20.0 | 1.5 | 19.4 | 1.5 | 20.5 | 1.7 | 20.0 | 1.6 | |

| SMMI (kg/m2) | Pre | 11.5 | 1.0 | 11.1 | 0.8 | 11.7 | 1.1 | 11.4 | 1.0 |

| Post | 11.3 | 0.9 | 11.0 | 0.9 | 11.6 | 1.0 | 11.3 | 1.0 | |

| AFFMI (kg/m2) | Pre | 8.4 | 0.7 | 8.1 | 0.5 | 8.8 | 0.9 | 8.4 | 0.7 |

| Post | 8.3 | 0.5 | 8.1 | 0.6 | 8.7 | 0.8 | 8.3 | 0.7 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Pre | 26.9 | 2.3 | 25.2 | 2.5 | 28.1 | 5.2 | 26.7 | 3.6 |

| Post | 26.2 | 2.2 | 24.4 | 2.6 | 27.1 | 4.9 | 25.9 | 3.5 | |

| PBF (%) | Pre | 24.2 | 5.8 | 21.7 | 6.0 | 25.1 | 7.7 | 23.6 | 6.4 |

| Post | 23.4 | 5.8 | 19.8 | 6.6 | 23.6 | 8.0 | 22.2 | 6.8 | |

| FMI (kg/m2) | Pre | 6.6 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 6.4 | 2.6 |

| Post | 6.2 | 2.0 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 6.7 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 2.6 | |

| VFA (cm2) | Pre | 81.2 | 33.3 | 67.7 | 25.4 | 96.8 | 44.3 | 81.1 | 35.6 |

| Post | 76.1 | 33.2 | 59.1 | 26.7 | 88.3 | 44.2 | 73.8 | 35.9 | |

| ICW/ECW | Pre | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

| Post | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | |

| SE | p- | Location | 95% CI | Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Test | Statistic | df | Difference | value | Parametera | Lower | Upper | Sizeb |

| Body mass (kg) | T-test | -9.378 | 36 | 0.252 | <.001 | -2.4 | -2.9 | -1.9 | -1.5 |

| Fat Mass (kg) | T-test | -7.752 | 36 | 0.208 | <.001 | -1.6 | -2.0 | -1.2 | -1.3 |

| FFM (kg) | T-test | -3.622 | 36 | 0.207 | <.001 | -0.8 | -1.2 | -0.3 | -0.6 |

| SMM (kg) | T-test | -3.691 | 36 | 0.116 | <.001 | -0.4 | -0.7 | -0.2 | -0.6 |

| AFFM (kg) | T-test | -2.842 | 36 | 0.088 | 0.007 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.1 | -0.5 |

| FFMI (kg/m2) | Wilcoxon | 117 | 36 | 0.068 | <.001 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.1 | -0.6 |

| SMMI (kg/m2) | Wilcoxon | 114 | 36 | 0.038 | <.001 | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.1 | -0.7 |

| AFFMI (kg/m2) | Wilcoxon | 173 | 36 | 0.029 | 0.006 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | -0.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | T-test | -9.603 | 36 | 0.083 | <.001 | -0.8 | -1.0 | -0.6 | -1.6 |

| FMI (kg/m2) | T-test | -7.657 | 36 | 0.070 | <.001 | -0.5 | -0.7 | -0.4 | -1.3 |

| PBF (%) | T-test | -5.531 | 36 | 0.247 | <.001 | -1.4 | -1.9 | -0.9 | -0.9 |

| VFA (cm2) | T-test | -8.752 | 36 | 0.834 | <.001 | -7.3 | -9.0 | -5.6 | -1.4 |

| Week | N | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPAQ (Met·min/week) | 0 | 37 | 1443 | 1053 |

| 1 | 37 | 1336 | 1051 | |

| 2 | 37 | 1089 | 823 | |

| 3 | 37 | 1139 | 800 | |

| 4 | 37 | 1189 | 1012 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 0 | 37 | 118 | 10 |

| 1 | 37 | 118 | 9 | |

| 2 | 37 | 117 | 8 | |

| 3 | 37 | 116 | 8 | |

| 4 | 37 | 117 | 10 | |

| DBP (mgHg) | 0 | 37 | 69 | 9 |

| 1 | 37 | 68 | 8 | |

| 2 | 37 | 67 | 8 | |

| 3 | 37 | 67 | 9 | |

| 4 | 37 | 68 | 8 | |

| FG (mmol) | 0 | 36 | 5.3 | 0.4 |

| 1 | 37 | 5.1 | 0.3 | |

| 2 | 37 | 5.3 | 0.4 | |

| 3 | 36 | 5.1 | 0.4 | |

| 4 | 37 | 5.2 | 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).