Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

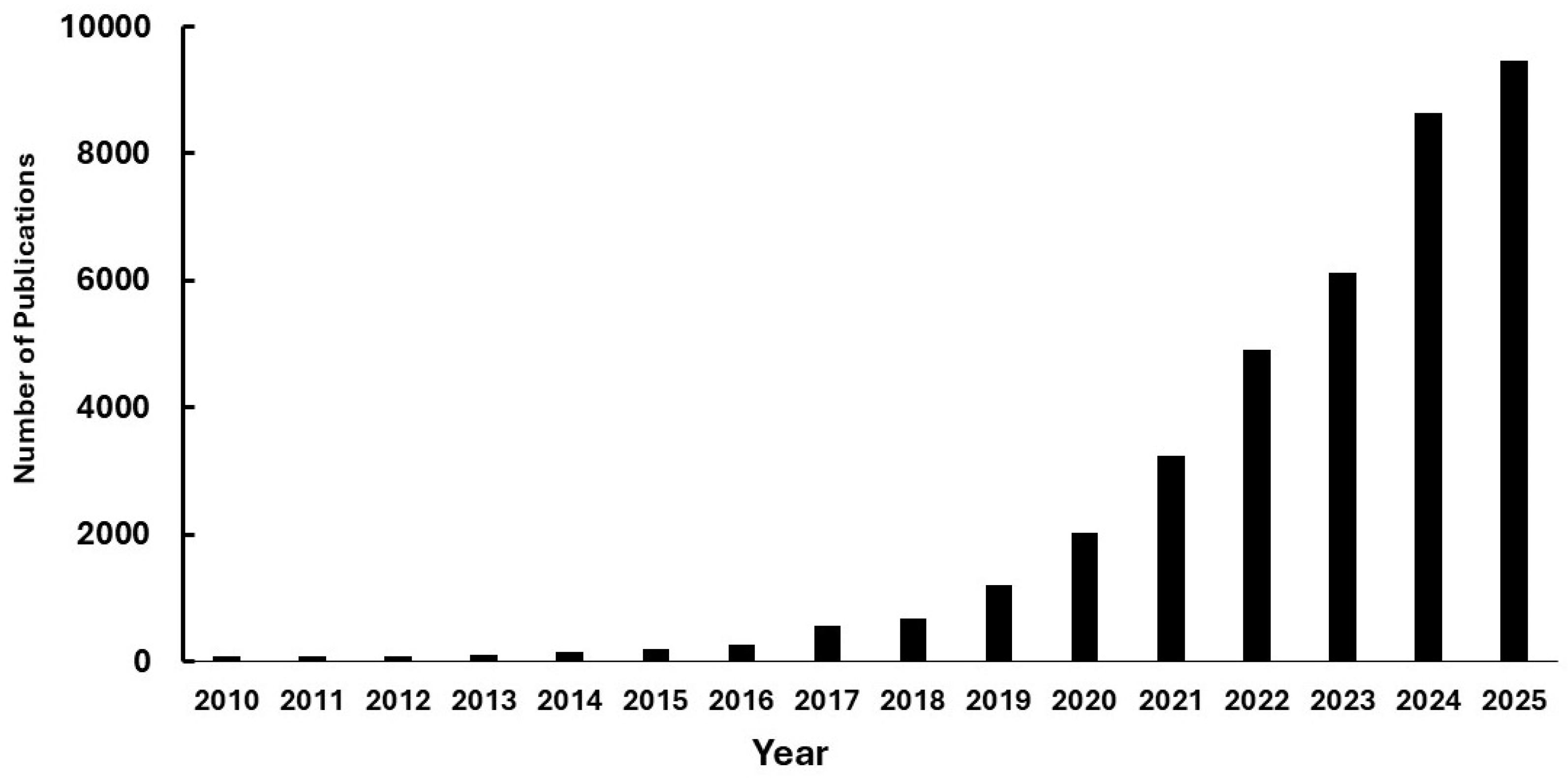

1. Plastics and Microplastics

1.1. Definition of Plastics: Types and Properties

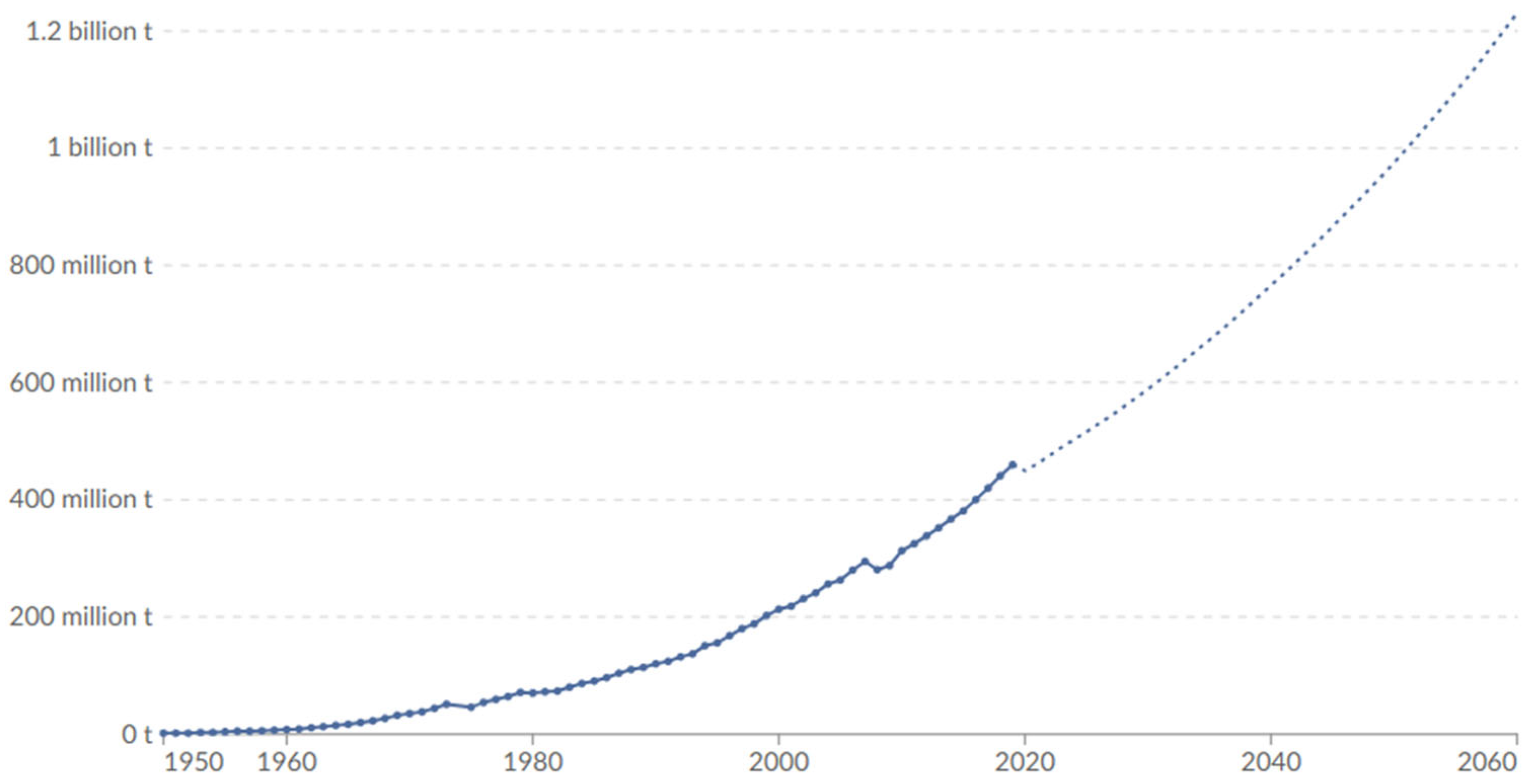

1.2. Plastic Production has More than Doubled in the Last Two Decades

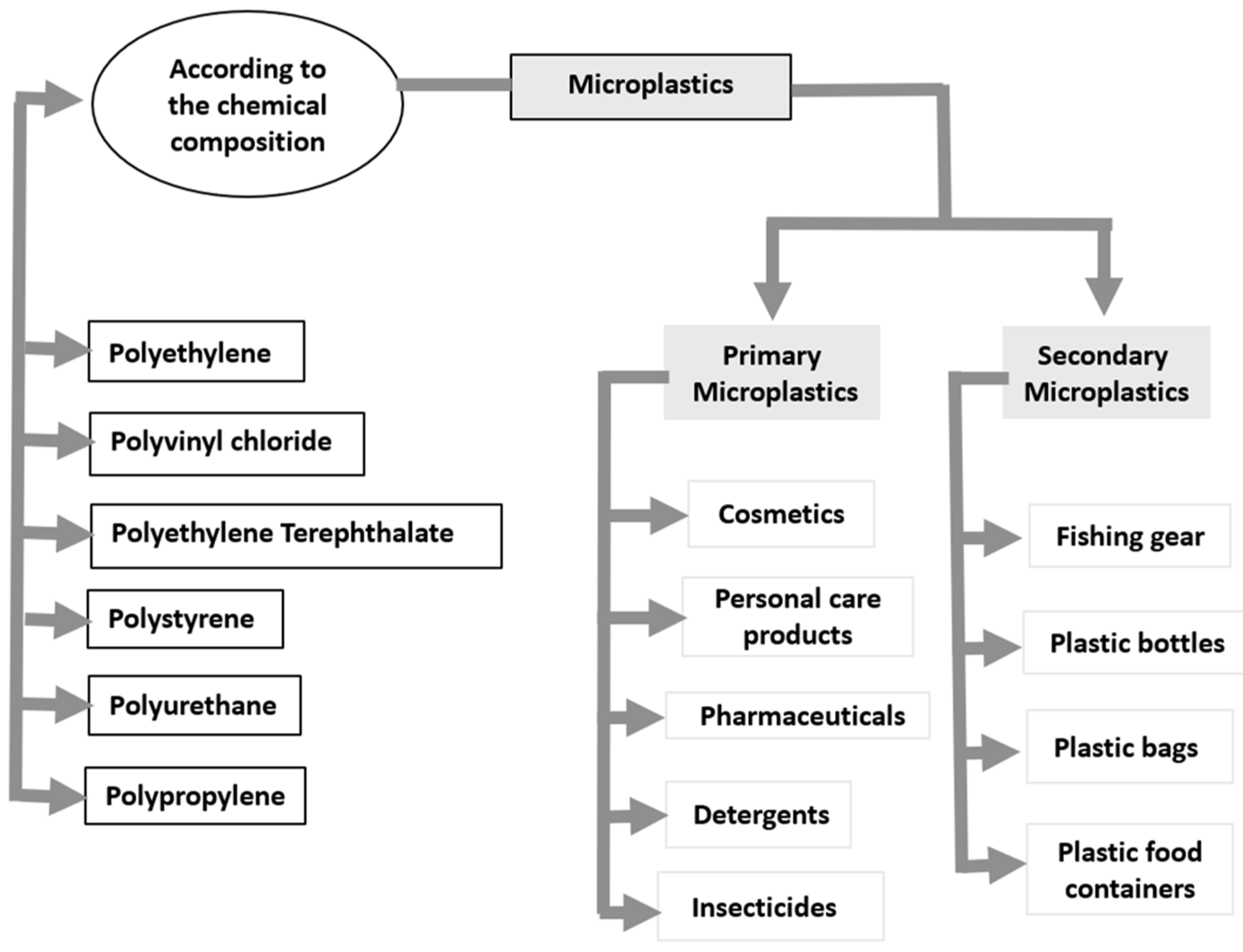

1.3. Types of Microplastics

1.3.1. Primary Microplastics

1.3.2. Secondary Microplastics

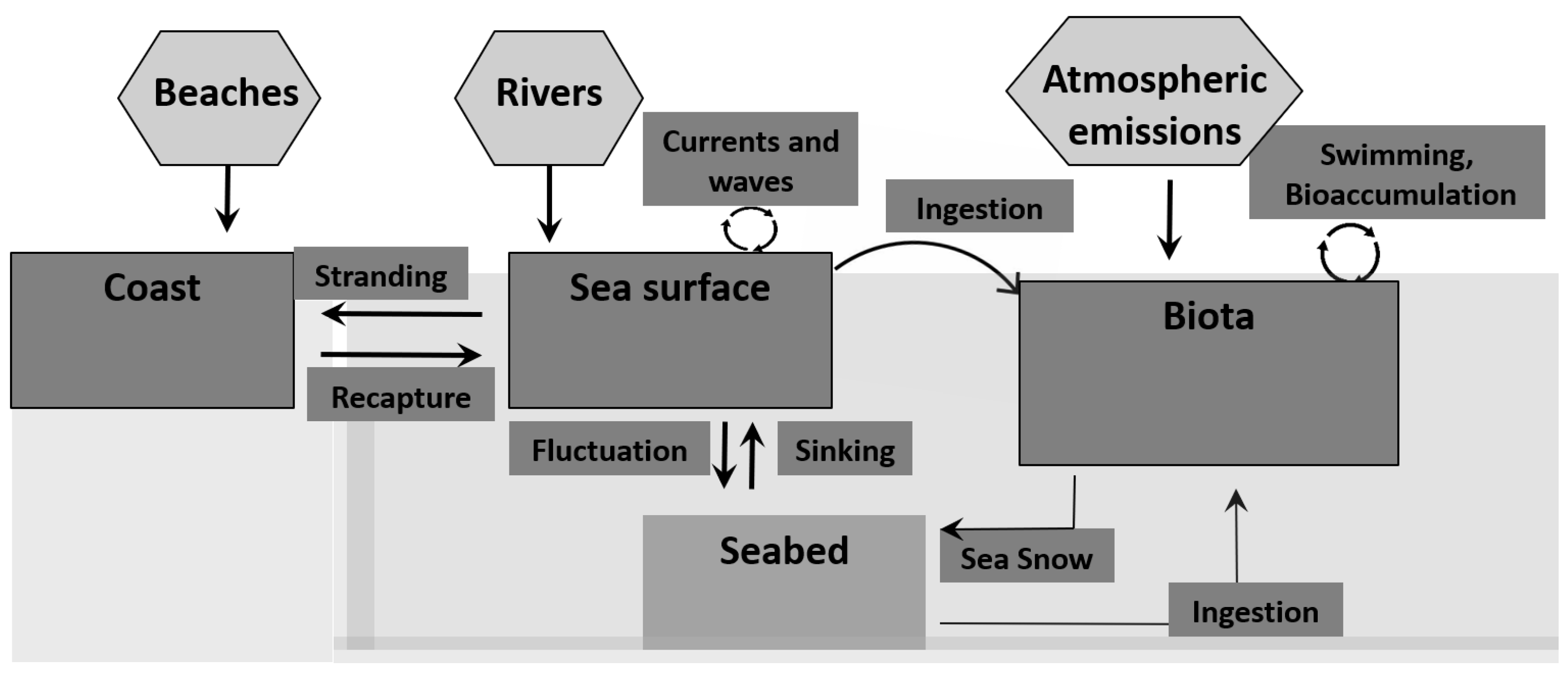

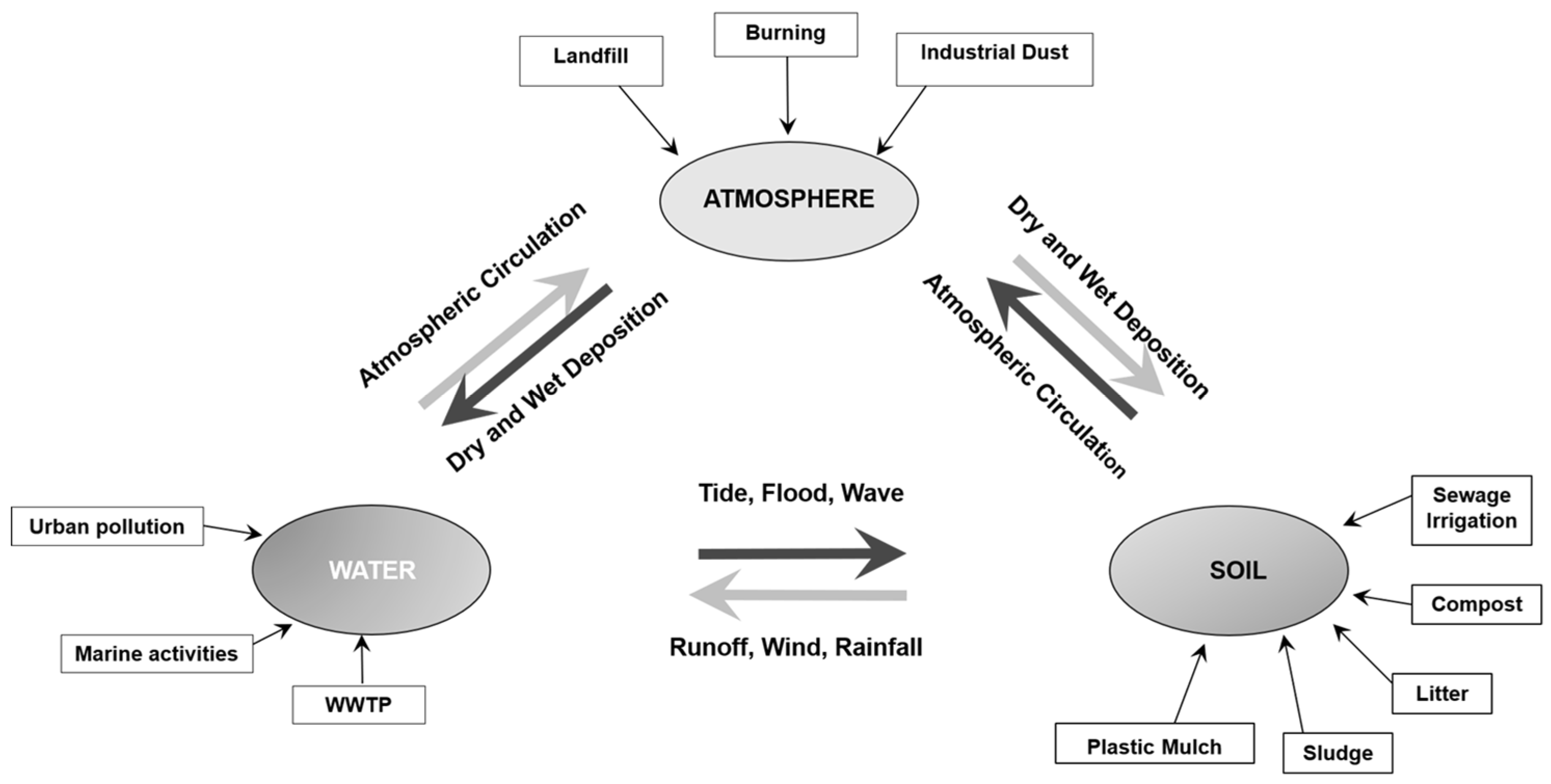

1.4. Microplastics in the Environment—Source and Characteristics

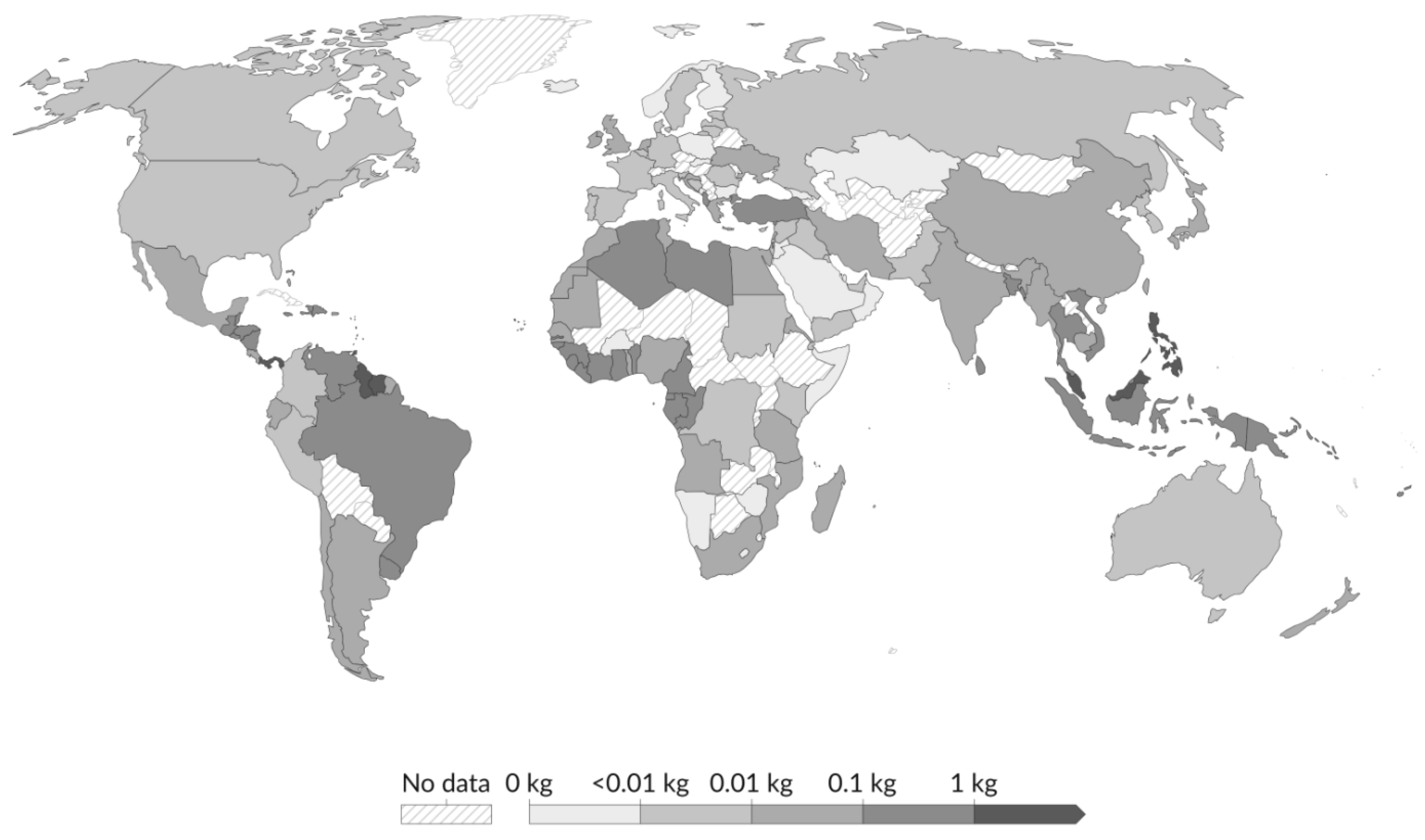

1.5. -Main Sources of Microplastics and Their Distribution

1.6. Hazard and Risks Associated with the Release of Microplastics

1.6.1. Plastic Ingestion by Marine Biota

1.6.2. Plastic as a Source and a Vector of Potential Toxins

1.6.3. Microplastics and Derivatives in Marine Organisms

1.7. Adverse Effects on the Organisms Caused by Microplastic Ingestion

1.8. Microplastics and Domestic Wastewaters—The Critical Importance of Microfibers

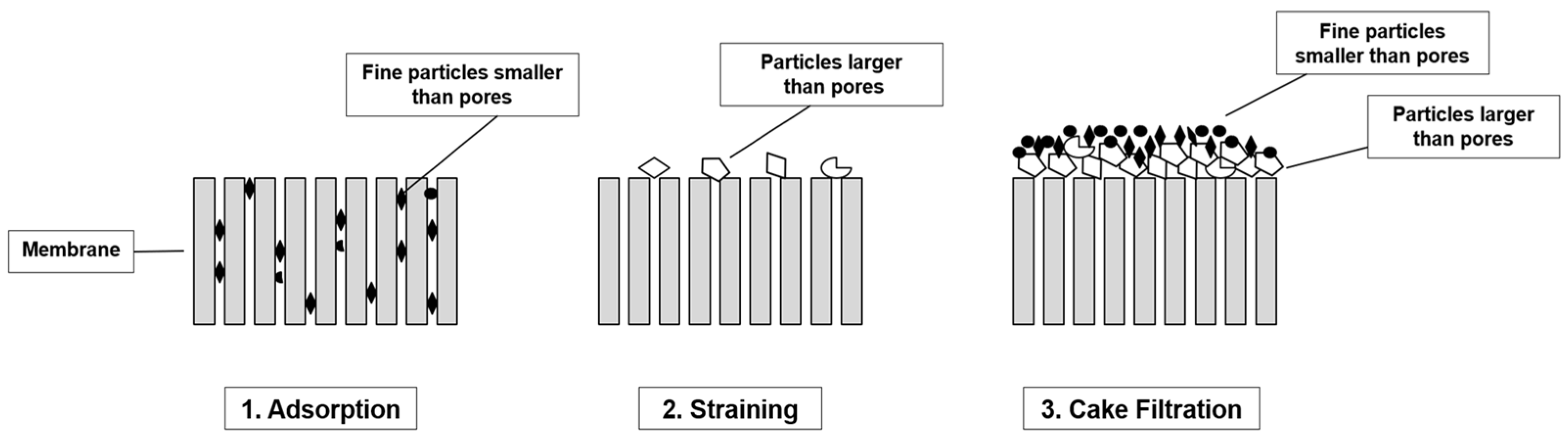

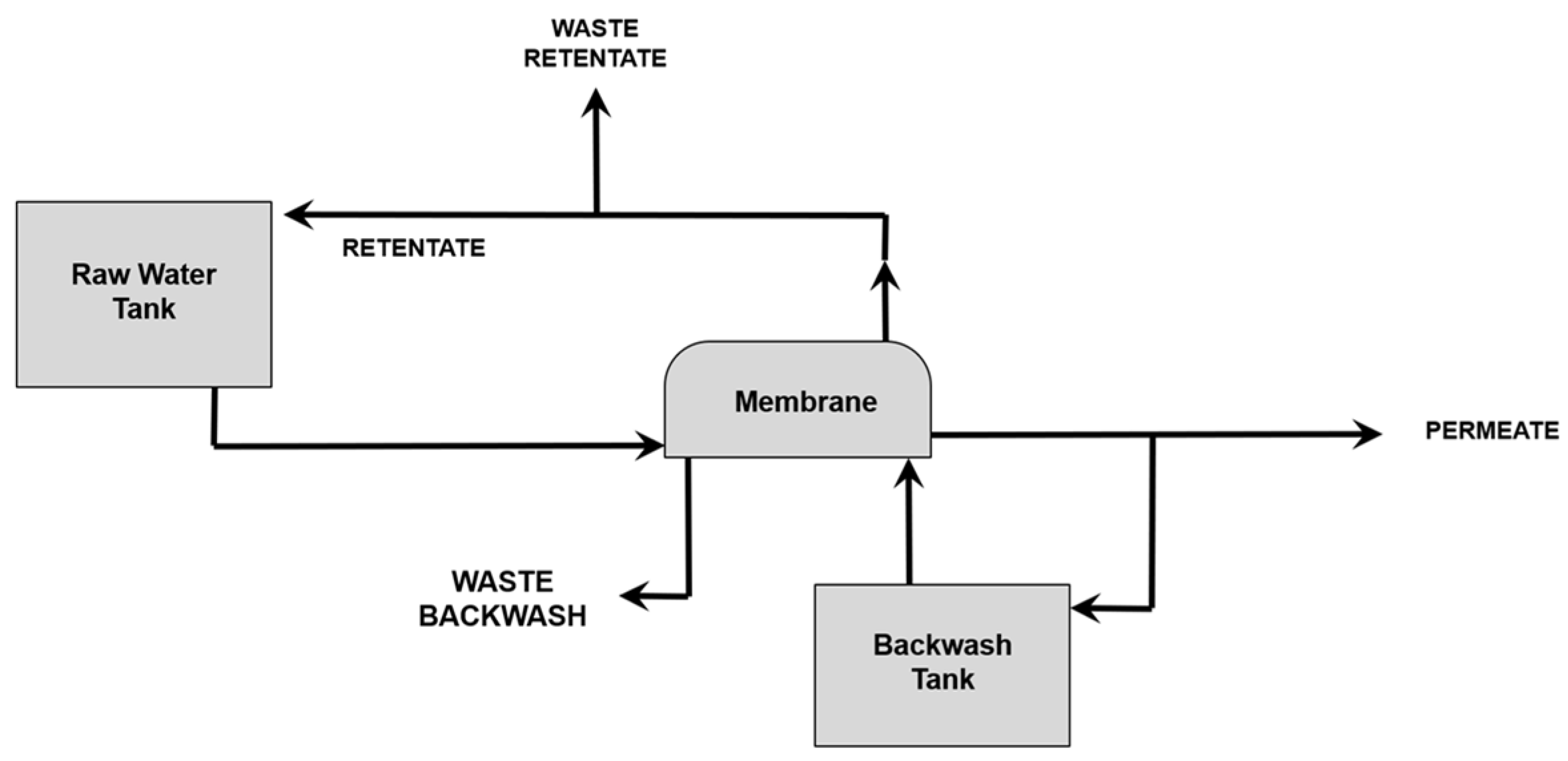

2. Processes Associated with Microplastic Removal

2.1. Membrane Applications in Water Treatment

2.2. Membrane Filtration—Typology and Properties

2.3. Membrane Properties and Performances

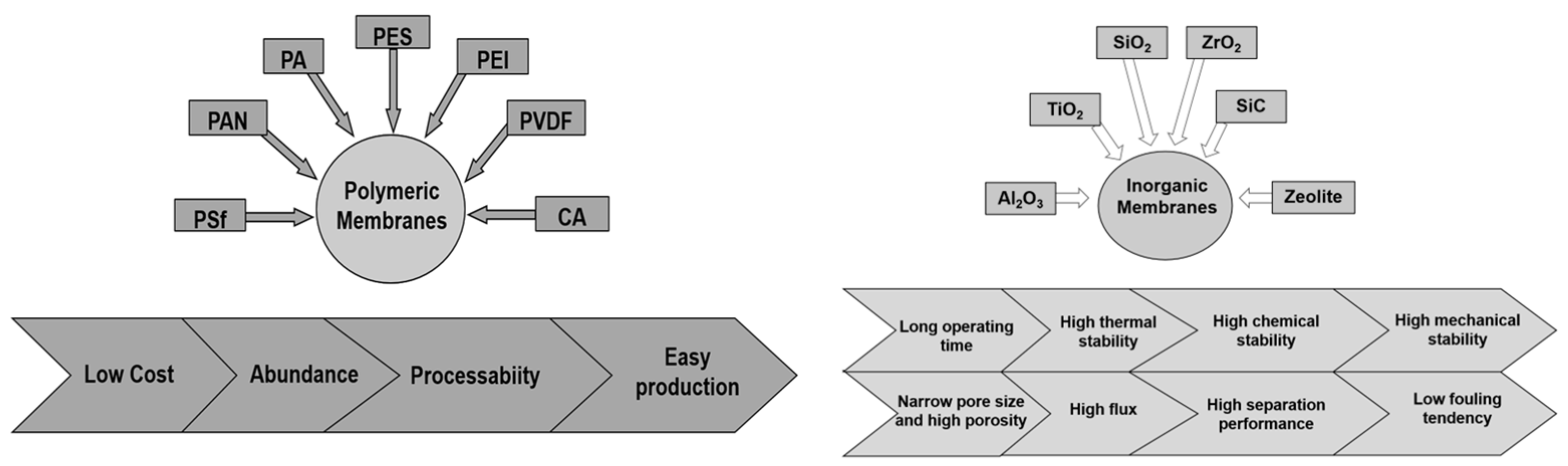

2.3.1. Polymeric Membranes

2.3.2. Inorganic Membranes

3. Characterization of Different Membranes and Filtration Processes Involved in MP

3.1. Microfiltration Membranes

3.2. Ultrafiltration

3.3. Nanofiltration

3.4. Reverse Osmosis

3.5. Membrane Bioreactors

3.6. Dynamic Membranes Technology

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv 2017, 3, e1700782. [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, R.; Siegler, T. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 6223, 768–771. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.P.; Santos, P.S.M; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. (Nano)plastics in the environment—Sources, fates and effects. Sci Total Environ 2016, 1, 2566-567, 15-26. [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, Z.; Guven, B. Microplastics in the Environment: A Critical Review of Current Understanding and Identification of Future Research Needs. Environ Pollut 2019, 113011. [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J.; Mikola, A.; Koistinen, A.; Setala, O. Solutions to microplastic pollution, removal of microplastics from wastewater effluent with advanced wastewater treatment technologies. Water Res 2017, 401-407. [CrossRef]

- Catic, I.; Cvjeticanin, N.; Galic, K.; Godec, D.; Grancaric, A.M.; Katavic’, I.; Raos, P.; Rogic, A. Polimeri—Od prapočetka do plastike i elastomera. Polimeri 2020, 31, 59–70.

- Van der Vegt, A.K. From Polymers to Plastics, Delft University Press, 2006, pp. 255-263.

- Sazali, N.; Ibrahim, H.; Jamaludin, A.S. A short review on polymeric materials concerning degradable polymers. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 88, 012047.

- Šaravanja, A.; Pušić, T.; Dekanić, T. Microplastics in wastewater by washing polyester fabrics. Materials 2022, 15, 7, 2683. [CrossRef]

- Issac, M.N.; Balasubramanian, K. Effect of microplastics in water and aquatic systems. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 19544–19562. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C.E.; Esteban, M.A.; Cuesta, A. Microplastics in aquatic environments and their toxicological implications for fish. In Toxicology—New Aspects to This Scientific Conundrum, 2016, Rijeka, InTech, pp. 113–145. [CrossRef]

- GESAMP, Sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment (Part 1), 2016. [Online].

- Andrady, A.L.; Neal, M.A. Applications and societal benefits of plastics, Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B Biol Sci 2009, 364, 1977–1984. [CrossRef]

- van Sebille, E.; Wilcox, C.; Lebreton, L. A global inventory of small floating plastic debris. Environ Res Lett 2015, 10, 124006. [CrossRef]

- Hale, R.C.; Seeley, M.E.; La Guardia, M.J.; Mai, L.; Zeng, E.Y. A Global Perspective on Microplastics. J Geophys Res. Oceans, 2020, 125, e2018JC014719. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, L.J.; van Emmerik, T.; van der Ent, R.; Schmidt, C.; Lebreton, L. More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- OECD, Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2022.

- Rillig, M.C.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, T.Y.; Waldman, W. The Global Plastic Toxicity Debt. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 5, 2717–2719. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. The Plastic Cycle—an Unknown Branch of the Carbon Cycle. Front Mar Sci 2021, 609243. [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: a review. Mar Pollut Bull 2011, 62, 2588–2597. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.C.; Rosenberg, M.; Cheng, L. Increased oceanic microplastic debris enhances oviposition in an endemic pelagic insect. Biol Lett 2012, 8, 5, 817–820. [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Niven, S.J.; Galloway, T.S.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C. Microplastic moves pollutants and additives to worms, reducing functions linked to health and biodiversity. Curr Biol 2013, 23, 23, 2388–2392. [CrossRef]

- Poerio, T.; Piacentini, E.; Mazzei, R. Membrane Processes for Microplastic Removal. Molecules 2019, 24, 22, 4148. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.; Wagner, M. Characterisation of nanoplastics during the degradation of polystyrene. Chemosphere 2016, 145, 265–268. [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Bakir, A.; Rowland, S.J. Characterisation, quantity and sorptive properties of microplastics extracted from cosmetics. Mar Pollut Bull, 2015, 99, 178–185. [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.P.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition. Mar Pollut Bull 2019, 138,145-147.. [CrossRef]

- Egessa, R.; Nankabirwa, A.; Ocaya, H.; Pabire, W.G. Microplastic pollution in surface water of Lake Victoria. Sci Total Environ 2020, 741. [CrossRef]

- Samandra, S.; Johnston, J.M; Xie, S.; Currell, M.; Ellis, A.V.; Clarke, B.O. Microplastic contamination of an unconfined groundwater aquifer in Victoria, Australia. 2022, 802, 149727. [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.A.; Arellano, J.P.; Albendín, G.; Rodríguez-Barroso, R.; Quiroga, J.M.; Coello, M.D. Microplastic pollution in wastewater treatment plants in the city of Cádiz: Abundance, removal efficiency and presence in receiving water body. Sci Total Environ 2021, 776, 145795. [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Jiang, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhong, X. Occurrence and identification of microplastics in tap water from China. Chemosphere, 2020. 252, 126493. [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Welch, V.G.; Neratko, J. Synthetic Polymer Contamination in Bottled Water. Front Chem 2018, 6, 407. [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S. The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: A review. Environ Pollut 2013, 178, 483–492. [CrossRef]

- Velasco, A.N.; Stéphan, R.G.; Zimmermann, S.; Le Coustumer, P.; Stoll, S. Contamination and removal efficiency of microplastics and synthetic fibres in a conventional drinking water treatment plant in Geneva, Switzerland. Sci Total Environ 2023, 880, 163270. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N. B.; Hüffer, T.; Thompson, R.R.; Hassellöv, M.; Verschoor,A.; Daugaard, A.E.; Rist, S.; Karlsson, T.; Wagner, M. Are We Speaking the Same Language? Recommendations for a Definition and Categorization Framework for Plastic Debris. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, 1039−1047. [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Hosny, M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Omar, S.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Farghali, M.; Yap, P.S.; Wu, Y.S.; Nagandran, S.; Batumalaie, K.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; John, O.D.; Sekar, M.; Saikia, T.; Karunanithi, P.; Hatta, M.H.M.; Akinyede, K.A. Microplastic sources, formation, toxicity and remediation: a review. Environ Chem Lett 2023, 1-41. [CrossRef]

- Amaral-Zettler, L.; Dudas, S.; Fabres, J.; Galgani, F.; Hardesty, D.; Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Hong, S.; Kershaw, P.; Lebreton, L.; Lusher, A.; Narayan, R.; Pahl, S.; Ziveri, P. Sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment: Part 2 of a global assessment. 2016, 93, 217.

- Leslie, H.A. Review of Microplastics in Cosmetics: Scientific background on a potential source of plastic particulate marine litter to support decision-making. IVM Institute for Environmental Studies, vol. 476, p. 33, 2014.

- Skalle, P.; Backe, K. R.; Lyomov, S.K.; Killas, L.D.; Dyrli, D.; Sveen, J. Microbeads as Lubricant in Drilling Muds Using a Modified Lubricity Tester. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, p. SPE 56562, 1999.

- Sundt, P.; Schulze, P.; Syversen, F. Sources of microplastic-pollution to the marine environment (MEPEX). 2014.

- Magnusson, K. K.; Eliasson, K.; Fråne, A.; Haikonen, K.; Hultén, J.; Olshamma, M.; Stadmark, J.; Voisin, A.; Stadmark, J.; Voisin, A. Swedish sources and pathways for microplastic to the marine environment: a review of existing data. IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute Report, 2016.

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic?, Science 2004, 304, 5672, 838. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, M; Han, G.M.; Jung, S.W.; Shim, W.J. Combined effects of UV exposure duration and mechanical abrasion on microplastic fragmentation by polymer type. Environ Sci Techn 2014, 48, 8963-8970. [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.C.; Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Lee, J.S.; Shim, W.J. Sources of plastic marine debris on beaches of Korea: More from the ocean than the land. Ocean Sci J 2014, 49, 2, 151–162. [CrossRef]

- Adachi, K.; Tainosho, Y. Characterization of heavy metal particles embedded in tire dust. Environ Int 2004, 30, 8, 1009–1017. [CrossRef]

- Jartun, M.; Pettersen, A. Contaminants in urban runoff to Norwegian fjords. J Soils Sediments 2010, 10, 2, 155–161. [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.F.; Harrad, S.; Millette, J.R.; Holbrook, R.D.; Davis, J.M.; Stapleton, H.M.; McClean, M.D.; Ibarra, C.; Abdallah, M.A. Environmental Science and Technology. Identifying transfer mechanisms and sources of decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE 209) in indoor environments using environmental forensic microscopy. 43, 9, 3067–3072, 2009.

- Cornelissen, G.; Pettersen, A.; Nesse, E.; Eek, E.; Helland, A.; Breedveld, G.D. The contribution of urban runoff to organic contaminant levels in harbour sediments near two Norwegian cities. Mar Pollut Bull 2008, 56, 3, 565–573. [CrossRef]

- Zgheib, S.; Moilleron, R.; Saad, M.; Chebbo, G. Partition of pollution between dissolved and particulate phases: What about emerging substances in urban stormwater catchments? Water Res 2011, 45, 2, 913–925. [CrossRef]

- Arp, H.P.; Møskeland, T.; Andersson, P.L.; Nyholm, J.R. Presence and partitioning properties of the flame retardants pentabromotoluene, pentabromoethylbenzene and hexabromobenzene near suspected source zones in Norway. J Environ Monit 2011, 3, 13, 505–513. [CrossRef]

- Danon-Schaffer, M.N; Mahecha-Botero, A.; Grace, J.; Ikonomou, M. Transfer of PBDEs from e-waste to aqueous media. Sci Total Environ 2013, 447, 458–471. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.A.; Corcoran, P.L. Effects of mechanical and chemical processes on the degradation of plastic beach debris on the island of Kauai, Hawaii. Mar Pollut Bull, 2010, 60, 5, 650–654. [CrossRef]

- Pegram, J.E.; Andrady, A.L. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 26, 4, 333–345, 1989.

- Arthur, C.; Baker, J.; Bamford, H. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects, and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris. Vols. 1 and 2 University of Washington, Tacoma, WA, USA, September 9-11, 2009.

- Wagner, M.; Lambert, S. Microplastics are contaminants of emerging concern in freshwater environments: an overview. Freshwater Microplastics., M. Wagner, S. Lambert, Edits., Springer., 2018.

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: a review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R.C. Microplastic—an emerging contaminant of potential concern? Integr Environ Assess Manag 2007, 3(4), 559-61. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Xia, J. A review on the occurrence, distribution, characteristics, and analysis methods of microplastic pollution in ecosystems. Environ Pollut Bioavail 2021. 33, 1, 227-246. [CrossRef]

- Vermeiren, P.; Muñoz, C.; Ikejima, K. Microplastic identification and quantification from organic-rich sediments: a validated laboratory protocol. Environ Pollut 2020, 262, 114298. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F. Wastewater treatment works (WWTW) as a source of microplastics in the aquatic environment. Environ Sci Technol 2016, 50, 11, 5800–5808. [CrossRef]

- Cesa, F.S.; Turra, A.; Baruque-Ramos, J. Synthetic fibers as microplastics in the marine environment: a review from a textile perspective with a focus on domestic washings. Sci Total Environ 2017, 598, 1116–1129. [CrossRef]

- Laresa, M.; Ncibi, M.C.; Sillanpää, M. Occurrence, Identification and removal of microplastic particles and fibers in conventional activated sludge process and advanced MBR technology. Water Res 2018, 133, 236–246. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Shi, H.; Peng, J. Microplastic pollution in China’s inland water systems: a review of findings, methods, characteristics, effects, and management. Sci Total Environ 2018, 630, 1641–1653. [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci Total Environ 2017, 586, 127–141. [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M. Microplastics research: from sink to source. Science, 2018, 360, 6384, 28–29. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F. Distribution and potential health impacts of microplastics and microrubbers in air and street dusts from Asaluyeh County, Iran. Environ Pollut 2019, 244, 153-164. [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Fu, D.; Qi, H. Micro- and nano-plastics in marine environment: source, distribution and threats—A review. Sci Total Environ 2020, 698, 134254. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Mason, S.; Wilson, S. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of the Laurentian great lakes. Mar Pollut Bull 2013, 77, 1, 177–182. [CrossRef]

- Obbard, R.W.; Sadri, S.; Wong, Y.Q. Global warming releases the microplastic legacy frozen in Arctic Sea ice. Earth’ Future 2014, 2, 6, 315–320. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, W. Microplastic abundance, distribution and composition in water, sediments, and wild fish from Poyang Lake, China. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019, 170, 180–187. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Microplastics in agricultural soils on the coastal plain of Hangzhou Bay, east China: multiple sources other than plastic mulching film. J. Hazard Mater 2019, 388, 121814. [CrossRef]

- Gasperi, J.; Wright, S.L.; Dris, R. Microplastics in air: are we breathing it in? Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 2018, 1, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Sighicellia, M.; Pietrelli, L.; Lecce, F. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of Italian Subalpine Lakes. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 645–651. [CrossRef]

- Panno, S.V.; Kelly, W.R.; Scott, J. Microplastic contamination in Karst groundwater systems. Ground Water 2019, 57, 2, 189–196. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Chen, L. Microplastics in soils: a review of possible sources, analytical methods and ecological impacts. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 2020, 95, 8, 2052–2068. [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Stock, F. Massarelli, C. Microplastics and their possible sources: the example of the Ofanto river in Southeast Italy. Environ Pollut 2019, 258, 113284. [CrossRef]

- Eerkes-Medrano, D.; Thompson, R.C.; Aldridge, D.C. Microplastics in freshwater systems: a review of the emerging threats, identification of knowledge gaps and prioritisation of research needs. Water Res 2015, 75, 63–82. [CrossRef]

- Mai, L.; You, S.N., He, H. Riverine microplastic pollution in the Pearl River Delta, China: are modelled estimates accurate? Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, 20, 11810–11817. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Krauth, T.; Wagner, S. Export of plastic debris by rivers into the sea. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, 21, 12246–12253. [CrossRef]

- Ivleva, N. P.; Wiesheu, A.C; Niessner, R. Microplastics in aquatic ecosystems. Angew. Chem Int Ed Engl 2017, 56, 7, 1720–1739. [CrossRef]

- Hardesty, B. D.; Lawson, T.J.; van der Velde, T. Estimating quantities and sources of marine debris at a continental scale. Front Ecol Environ 2017, 15, 1, 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O. S.; Budarz, J.F.; Hernandez, L.M. Microplastics and nanoplastics in aquatic environments: aggregation, deposition, and enhanced contaminant transport. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52, 4, 1704–1724. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, S. Microplastics contaminate the deepest part of the world’s ocean. Geochem Perspect Lett 2018, 9, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhu, L.; Teng, W. Suspended microplastics in the surface water of the Yangtze Estuary System, China: first observations on occurrence, distribution. Mar Pollut Bull 2014, 86, 1-2, 562–568. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Cao, W. Distribution characteristics of microplastics in the seawater and sediment: a case study in Jiaozhou Bay, China. Sci. Total Environ 2019, 674, 2, 7–35. [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, H.; Evans, S.W.; Cole, N.; Yive, N.S. The flip-or-flop boutique: Marine debris on the shores of St Brandon’s rock, an isolated tropical atoll in the Indian Ocean. Mar Environ Res 2016, 114, 58-64. [CrossRef]

- Kane, I.A.; Clare, M.A. Dispersion, accumulation, and the ultimate fate of microplastics in deep-marine environments: a review and future directions. Front Earth Sci 2019, 7, 80. [CrossRef]

- Law, K.L.; Moret-Ferguson, S.; Maximenko, N.A.; Proskurowski, G.; Peacock, E.E.; Hafner, J.; Redd. C.M. Plastic accumulation in the North Atlantic subtropical gyre. Science 2010, 329, 5996, 1185-1188. [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Saad, M. Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: a source of microplastics in the environment? Mar Pollut Bull 2016, 104,1-2, 290–293. [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V. Microplastic contamination in an urban area: a case study in Greater Paris. Environ Chem 2015, 12, 5, 592–599. [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat Geosci 2019, 5, 339– 334. [CrossRef]

- Villarrubia-Gómez, P.; Cornell, S.E.; Fabres, F. Marine plastic pollution as a planetary boundary threat—The drifting piece in the sustainability puzzle. Marine Policy 2018, 96, 213–220. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yan, Z.; Zhu, Q. Tissue accumulation of microplastics and toxic effects: widespread health risks of microplastics exposure. In: Microplastics in terrestrial environments, 2020, p. 1–21.

- Derraik, J,G. The pollution of the marine environment by plastic debris: a review. Mar Pollut Bull 2002, 44(9), 842-52. [CrossRef]

- Gall, S.C.; Thompson, R.C. The impact of debris on marine life. Mar Pollut Bull 2015, 92, 170-179. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Gutow, L.; Klages, M. Marine anthropogenic litter. Springer, 2015.

- Andrady, A.L. Persistence of plastic litter in the oceans. Marine anthropogenic litter, M. Bergmann, L. Gutow, M. Klages, Edits., Springer, 2015, pp. 57-72.

- Kershaw, P.; Katsuhiko, S.; Lee, S.; Samseth, J.; Woodring, D. Plastic Debris in the Ocean (pp. 20-33). United Nations Environmental Programme Year Book 2011.

- Rochman, C.M. The complex mixture, fate and toxicity of chemicals associated with plastic debris in the marine environment. In (Eds.), Marine anthropogenic litter, Berlin, Springer, 2015, p. 117–140.

- Thompson, R.C.; Moore, C.J.; vom Saal, F.S.; Swan, S.H. Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2009, 364(1526), 2153-66. [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Browne, M.A. Classify plastic waste as hazardous. Nature, 2013, 494, 169–171. [CrossRef]

- Lusher, A. Microplastics in the marine environment: distribution, interactions and effects. in Marine anthropogenic litter, M. Bergmann, L. Gutow, M. Klages, Edits., Berlin, Springer, 2015, pp. 245–308.

- Teuten, E.L.; Rowland, S.J.; Galloway, T.S.; Thompson, R.C. Potential for Plastics to Transport Hydrophobic Contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol, 2007, 41, 7759-7764. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.; Kraak, M.H.; Parsons, J.R. Plastics in the marine environment: the dark side of a modern gift. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2012, 220, 1-44. [CrossRef]

- Mato, Y.; Isobe, T.; Takada, H.; Kanehiro, H.; Ohtake, C.; Kaminuma, T. Plastic resin pellets as a transport medium for toxic chemicals in the marine environment. Environ Sci Technol, 2001, 35, 318–324. [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y.; Takada, H.; Master, M.K.; Hirai, H. International pellet watch: Global monitoring of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in coastal waters. Initial phase data on PCBs, DDTs, and HCHs. Mar Pollut Bull 2009, 58, 1437–1466. [CrossRef]

- Hirai, H.; Takada, H.; Ogata, Y.; Yamashita, R. Organic micropollutants in marine plastics debris from the open ocean and remote and urban beaches. Mar Pollut Bull 2011, 62, 8, 1683–16921. [CrossRef]

- Oehlmann, J.; Schulte-Oehlmann, U.; Kloas, W.; Jagnytsch, O.; Lutz, I.; Kusk, K.O.; Wollenberger, L.; Santos, E.M.; Paull, G.C.; Van Look, K.J.; Tyler, C.R. A critical analysis of the biological impacts of plasticizers on wildlife. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2009, 364(1526), 2047-62. [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A. Modeling the role of microplastics in bioaccumulation of organic chemicals to marine aquatic organisms. A critical review.” in Marine Anthropogenic Litter, M. Bergmann, L. Gutow e M. Klages, Edits., Berlin, Springer, 2015, p. 313–328.

- Murray, F.; Cowie, P.R. Plastic contamination in the decapod crustacean Nephrops norvegicus (Linnaeus, 1758). Mar Pollut Bull 2011, 62, 1207–1217. [CrossRef]

- Possatto, F.E.; Barletta, M.; Costa, M.F.; do Sul, J.; Dantas, D.V. Plastic debris ingestion by marine catfish: An unexpected fisheries impact. Mar Pollut Bull. 2011, 62, 1098-1102. [CrossRef]

- van Franeker, J.A.; Blaize, C.; Danielsen, J.; Fairclough, K.; Gollan, J.; Guse, N. Monitoring plastic ingestion by the northern fulmar Fulmarus glacialis in the North Sea. Environ Pollut 2011, 159, 10, 2609–2615. [CrossRef]

- Foekema, E.M.; De Gruijter, C.; Mergia, M.T.; van Franeker, J.A.; Murk, A.J.; Koelmans, A.A. Plastic in North Sea fish. Environ Sci Technol 2013, 47, 8818–8824. [CrossRef]

- Lusher, A.; McHugh, M.; Thompson, R.C. Occurrence of microplastics in the gastrointestinal tract of pelagic and demersal fish from the English Channel. Mar Pollut Bull 2013, 67, 1-2, 94–99. [CrossRef]

- Rebolledo, E.L.; van Franeker, J.A.; Jansen, O.E.; Brasseur, S.M. Plastic ingestion by harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) in The Netherlands. Mar Pollut Bull 2013, 67, 200–202. [CrossRef]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Dehaut, A.; Paul-Pont, I.; Lacroix, C.; Jezequel, R.; Soudant, P.; Duflos, G. Occurrence and effects of plastic additives on marine environments and organisms: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 781-793.. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Lin, S.; Turner, J.P.; Ke, P.C. Physical Adsorption of Charged Plastic Nanoparticles Affects Algal Photosynthesis. J Phys Chem C 2010, 114, 39, 16556–16561. [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Panti, C.; Guerranti, C.; Coppola, D.; Giannetti, M.; Marsili, L.; Minutoli, R. Are baleen whales exposed to the threat of microplastics? A case study of the Mediterranean fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). Mar Pollut Bull 2012, 64(11), 2374-9. [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Coppola, D.; Baini, M.; Giannetti, M.; Guerranti, C.; Marsili, L.; Panti, C.; de Sabata, E.; Clò S. Large filter feeding marine organisms as indicators of microplastic in the pelagic environment: the case studies of the Mediterranean basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) and fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). Mar Environ Res 2014, 100, 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Zaki, M.R.; Zaid, S.H.; Zainuddin, A.H.; Aris, A.Z. Microplastic pollution in tropical estuary gastropods: Abundance, distribution and potential sources of Klang River estuary, Malaysia. Mar Pollut Bull 2021, 162, 11866. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Shim, W.J.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Hong, S. Nationwide monitoring of microplastics in bivalves from the coastal environment of Korea. Environ Pollut 2021, 270, 116175. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Su, L.; Ruan, H.D.; Chen, J.; Lu, J.L. Quantitative and qualitative determination of microplastics in oyster, seawater and sediment from the coastal areas in Zhuhai, China. Mar Pollut Bull 2021, 164, 112000. [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Galloway, T.S. Ingestion of nanoplastics and microplastics by Pacific oyster larvae. Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49, 24, 14625-14632. [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Fudalewska, D.; Normant-Saremba, M.; Anastácio, P. Occurrence of plastic debris in the stomach of the invasive crab Eriocheir sinensis. Mar Pollut Bull 2016, 113, 1-2, 306-311. [CrossRef]

- Welden, N.A.; Cowie, P.R. Environment and gut morphology influence microplastic retention in langoustine, Nephrops norvegicus. Environ Pollut 2016, 214, 859-865. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Russell, M.; Ewins, C.; Quinn, B. The uptake of macroplastic and microplastic by demersal and pelagic fish in the Northeast Atlantic around Scotland. Mar Pollut Bull 2017, 122, 1-2, 353-359. [CrossRef]

- Nadal, M. A.; Alomar, C.; Deudero, S. High levels of microplastic ingestion by the semi-pelagic fish bogue Boops boops (L.) around the Balearic Islands. Environ Pollut 2016, 214, 517-523. [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, K.; Huang, Y.; Yan, M. Microplastic pollution in water and fish samples around Nanxun Reef in Nansha Islands, South China Sea. Sci Total Environ 2019, 696, 134022. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, B.; Sun, X.; Qu, K.; Xia, B. Microplastic ingestion in deep-sea fish from the South China Sea. Sci Total Environ 2019, 677, 493-501. [CrossRef]

- Schuyler, Q.; Hardesty, B.D.; Wilcox, C.; Townsend, K. Global analysis of anthropogenic debris ingestion by sea turtles. Conserv Biol 2014, 28, 1, 129-39. [CrossRef]

- Clukey, K.E.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Balazs, G.H.; Work, T.M.; Lynch, J. Investigation of plastic debris ingestion by four species of sea turtles collected as bycatch in pelagic Pacific longline fisheries. Mar Pollut Bull 2017, 15, 120(1-2), 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Unger, B.; Rebolledo, E.L.; Deaville, R.; Gröne, A.; Jsseldijk, L.J.; Leopold, M.F.; Herr, H. Large amounts of marine debris found in sperm whales stranded along the North Sea coast in early. Mar Pollut Bull 2016, 112, 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Takada, H.; Yamashita, R.; Mizukawa, K.; Fukuwaka, M.A.; Watanuki, Y. Accumulation of plastic-derived chemicals in tissues of seabirds ingesting marine plastics. Mar Pollut Bull 2013, 69, 1-2, 219-222. [CrossRef]

- Nicastro, K.R.; Savio, R.L.; McQuaid, C.D.; Madeira, P.; Valbusa, U.; Azevedo, F.; Zardi, G. Plastic ingestion in aquatic-associated bird species in southern Portugal. Mar Pollut Bull 2018, 126, 413-418. [CrossRef]

- Wick, P.J.; Clift, M.J.; Roesslein, M.; Roth, B. A brief summary of carbon nanotubes science and technology: a health and safety perspective. Chemsuschem 2011, 4, 7, 905-911. [CrossRef]

- Berntsen, P.; Park, C.Y.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Tsuda, A.; Sager, T.M.; Molina, R.M; Zhou, E.H. Biomechanical effects of environmental and engineered particles on human airway smooth muscle cells. J R Soc Interface 2010, 7 (Suppl 3), S331-40. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, C.; Klitgaard, M.; Noer, J.B.; Kotzsch, A.; Nehammer, C.; Kronqvist, P.; Berthelsen, J.; Blobel, C.; Kveiborg, M.; Albrechtsen, R.; Wewer, U.M. ADAM12 is expressed in the tumour vasculature and mediates ectodomain shedding of several membrane-anchored endothelial proteins. Biochem J 2013, 452(1), 97-109. [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Fileman, E.; Halsband, C.; Goodhead, R.; Moger, J.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastic ingestion by zooplankton. Environ Sci Technol 2013, 47, 12, 6646-6655. [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.R.; Santana, M.F.; Maluf, A.; Cortez, F. S.; Cesar, A.; Pereira, C.D. Assessment of microplastic toxicity to embryonic development of the sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus (Echinodermata: Echinoidea). Mar Pollut Bull 2015, 92, 1-2, 99-104. [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.J. Synthetic polymers in the marine environment: a rapidly increasing, long-term threat. Environ Res 2008, 108, 2, 131-139. [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Rowe, D.; Thompson, R.C.; Gallow, T.S. Microplastic ingestion decreases energy reserves in marine worms. Curr Biol 2013, 23, 23, pp. R1031-R1033. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.R. Environmental implications of plastic debris in marine settings—entanglement, ingestion, smothering, hangers-on, hitch-hiking and alien invasions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2009, 364(1526), 2013-25. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, A.; Hylland, K.; Guilhermino, L. Single and combined effects of microplastics and pyrene on juveniles (0+ group) of the common goby Pomatoschistus microps (Teleostei, Gobiidae). Ecol Indic 2013, 34, 641-647. [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.K.; Perry, R.H.; Blessed, G.; Tomlinson, B.E. Changes in brain cholinesterases in senile dementia of Alzheimer type. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 1978, 4, 4, 273-7, 1978. [CrossRef]

- Pohanka, M.; Hrabinova, M.; Kuca, K.; Simonato, J.P. Assessment of acetylcholinesterase activity using indoxyl acetate and comparison with the standard Ellman’s method. Int J Mol Sci 2011, 12, 4, 2631-2640. [CrossRef]

- Mizukawa, K.; Takada, H.; Takeuchi, I.; Ikemoto, T.; Omori, K.; Tsuchiya, K. Bioconcentration and biomagnification of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) through lower-trophic-level coastal marine food web. Mar Pollut Bull 2009, 58(8), 1217-1224. [CrossRef]

- Teuten, E.L.; Saquing, J.M.; Knappe, D.R.; Barlaz, M.A.; Jonsson, S.; Björn, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Yamashita, R.; Ochi, D.; Watanuki, Y.; Moore, C.; Viet, P.H.; Tana, T.S., Prudente, M.; Boonyatumanond, R.; Zakaria, M.P.; Takada, H. Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2009 ,364(1526), 2027-45. [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F.; Fleet, D.; Van Franeker, J.A.; Katsanevakis, S.; Maes, T.; Mouat, J. Marine strategy framework directive-task group 10 report marine litter. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2010.

- Collard, F.; Gilbert, B.; Compère, P.; Eppe, G.; Das, K.; Jauniaux, T.; Parmentier, E. Microplastics in livers of European anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus, L.). Environ Pollut 2017, 229, 1000-1005. [CrossRef]

- Krogdahl, Å.; Kortner, T.M.; Hardy, R.W. Antinutrients and adventitious toxins. In Fish nutrition, Fish nutrition, Academic Press., 2022, pp. 775-821. [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Janssen, C.R. Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environ Pollut 2014, 193, 65-70. [CrossRef]

- Lehner, R.; Weder, C.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser B. Emergence of Nanoplastic in the Environment and Possible Impact on Human Health. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53(4), 1748-1765. [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.A.; Prasetya, T.A.E.; Dewi, I.R.; Ahmad, M. Microplastics in human food chains: Food becoming a threat to health safety. Sci Total Environ 2023, 858(Pt 1), 159834. [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A. Sources and pathways of microplastic to habitats. In Marine anthropogenic litter, M. Bergmann, L. Gutow, M. Klages, Edits., Berlin, Springer, 2015, pp. 229–244. [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines worldwide: sources and sinks. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45(21), 9175-9. [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Thompson, R.C. Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Mar Pollut Bull 2016, 112(1-2), 39-45. [CrossRef]

- Corami, F.; Rosso, B.; Bravo, B.; Gambaro, A.; Barbante, C. A novel method for purification, quantitative analysis and characterization of microplastic fibers using Micro-FTIR. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124564. [CrossRef]

- Belzagui, F.; Crespi, M.; Álvarez, A.; Gutiérrez-Bouzán, C.; Vilaseca, M. Microplastics’ emissions: Microfibers’ detachment from textile garments. Environ Pollut 2019, 248, 1028-1035. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.D. Microbiological deterioration and degradation of synthetic polymeric materials: Recent research advances. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 2003, 52, 69–91. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.A.; de Carvalho-Souza, G.F. Are we eating plastic-ingesting fish? Mar Pollut Bull 2016, 103(1-2), 109-114. [CrossRef]

- Muralikrishna I.V; Manickam, V. Wastewater Treatment Technologies. In Environmental Management, Butterworth-Heinemann, Elsevier, 2017, pp. 249-293. [CrossRef]

- Puteri, M.N.; Gew, L.T.; Ong, H.C.; Ming, L.C. Technologies to eliminate microplastic from water: Current approaches and future prospects. Environ Int. 2025, 199, 109397. [CrossRef]

- Gatidou, G.; Arvaniti, O.S.; Stasinakis, A.S. Review on the occurrence and fate of microplastics in Sewage Treatment Plants. J Hazard Mater. 2019, 367, 504-512. [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.A.; Liu, J.; Tesoro, A.G. Transport and fate of microplastic particles in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2016, 91, 174-82. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, Q.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Ni, B.J. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Detection, occurrence and removal. Water Res 2019, 152, 21-37. [CrossRef]

- Gündoğdu, S.; Çevik, C.; Güzel, E.; Kilercioğlu, S. Microplastics in municipal wastewater treatment plants in Turkey: a comparison of the influent and secondary effluent concentrations. Environ Monit Assess 2018, 190(11), 626. [CrossRef]

- Enfrin, M.; Dumée, L.F.; Lee, J. Nano/microplastics in water and wastewater treatment processes—Origin, impact and potential solutions. Water Res 2019, 161, 621-638. [CrossRef]

- Gray, N.F. Chapter Thirty-Five—Filtration Methods. In Microbiology of Waterborne Diseases, Second Edition, S. L. Percival, M. V. Yates, D. W. Williams, R. M. Chalmers e N. F. Gray, Edits., Academic Press, 2014, pp. 631-65.

- Othman, N.H.; Alias, N.H.; Fuzil, N.S.; Marpani, F.; Shahruddin, M.Z.; Chew, C.M.; David, Ng K.M.; Lau, W.J.; Ismail, A.F. A Review on the Use of Membrane Technology Systems in Developing Countries. Membranes (Basel) 2021, 12(1), 30. [CrossRef]

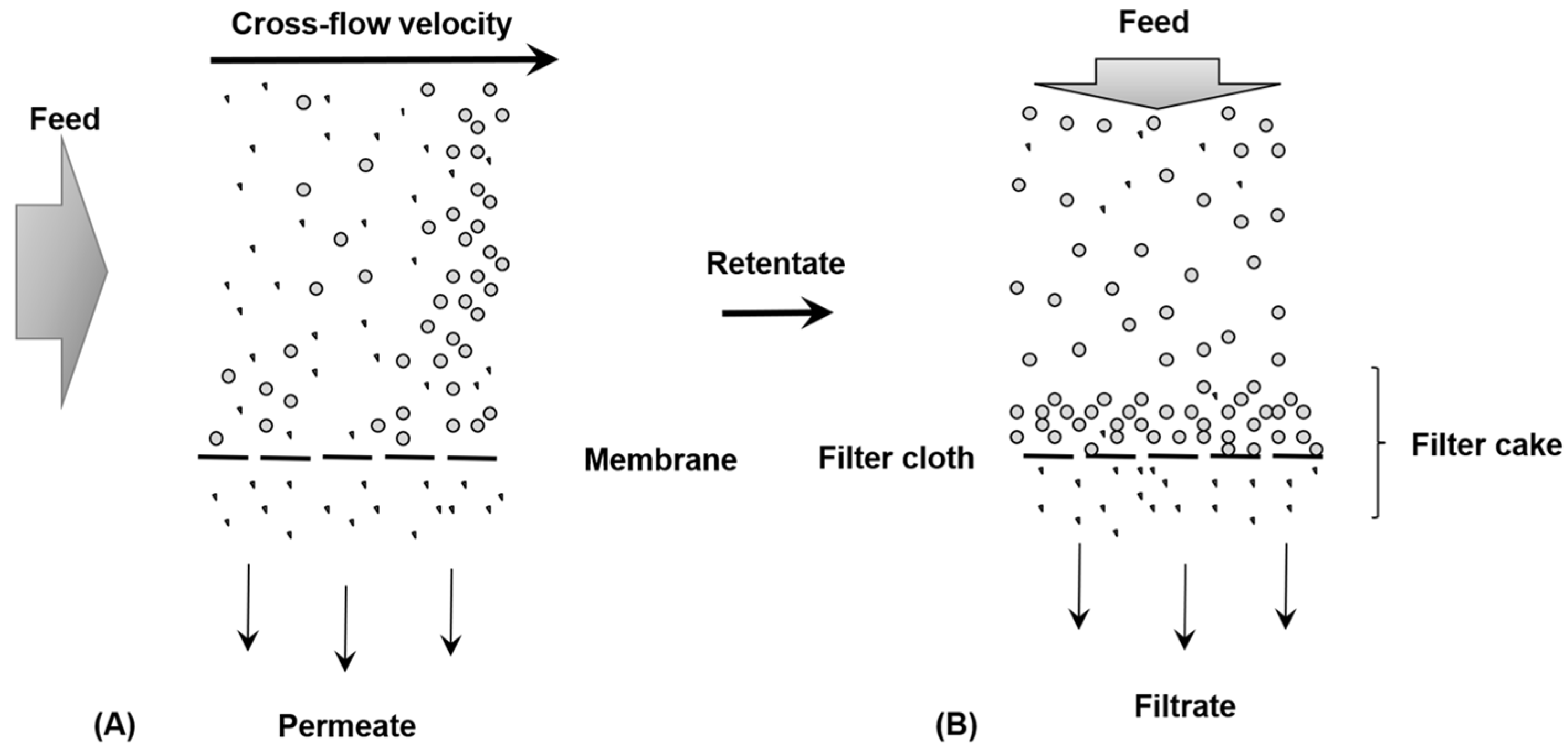

- Wang, Q.; Tang, X.; Liang, H.; Cheng, W.; Li, G.; Zhang, Q. Effects of filtration mode on the performance of gravity-driven membrane (GDM) filtration: cross-flow filtration and dead-end filtration. Water 2022, 14, 2, 190. doi.org/10.3390/w14020190.

- Vital, J.; Sousa, J.M. Polymeric membranes for membrane reactors. In Handbook of membrane reactor, vol. I, A. Basile, Ed., Woodhead Publishing, 2013, pp. 3-41.

- Algieri, C.; Chakraborty, S.; Pal, U. Efficacy of Phase Inversion Technique for Polymeric Membrane Fabrication. Journal of Phase Change Materials 2021. doi.org/10.6084/jpcm.v1i1.10.

- Arefi-Oskoui, S.; Khataee, A.; Jabbarvand, B.S.; Vatanpour, V.; Haddadi, G.S.; Orooji, Y. Development of MoS2/O-MWCNTs/PES blended membrane for efficient removal of dyes, antibiotic, and protein. Sep Purif Technol 2022, 280. [CrossRef]

- Farnam, M.; Bin, M.H.; Bin, M.S. A review on glassy and rubbery polymeric membranes for natural gas purification. Chem Bio Eng Reviews 2021, 8, 90-109. [CrossRef]

- Jain, H.; Garg, M.C. Fabrication of polymeric nanocomposite forward osmosis membranes for water desalination. A review. Environ Technol Innov 2021, 23, 101561, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Vatanpour, V.; Yavuzturk Gul, B.; Zeytuncu, B.; Korkut, S.; İlyasoğlu, G.; Turken, T.; Badawi, M.; Koyuncu, I.; Saeb, M.R. Polysaccharides in fabrication of membranes: A review. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 281, 119041. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, X.M.; Ursino, C.; Figoli, A.; Hoinkis, H.T. Removal of arsenic by nanofiltration: A case study on novel membrane materials.,” em Membrane Technologies for Water Treatment: Removal of Toxic Trace Elements with Emphasis on Arsenic, Fluoride and Uranium., London, CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group, 2016, pp. 201-214.

- Safikhani, A.; Vatanpour, V.; Habibzadeh, S.; Saeb, M.R. Application of graphitic carbon nitrides in developing polymeric membranes: A review. Chem Eng Res Des 2021, 173, 234-252. [CrossRef]

- Tahazadeh, S.; Mohammadi, T.; Tofighy, M.A.; Khanlari, S.; Karimi, H.; Motejadded Emrooz, H.B. Development of cellulose acetate/metal-organic framework derived porous carbon adsorptive membrane for dye removal applications. J Membr Sci 2021, 638, 119692. [CrossRef]

- Zugenmaier, P. Characterization and physical properties of cellulose acetates. Macromolecular Symposia 2004, vol. 208, pp. 81-166. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.R.; Sharma, S.K.; Lindstrom, T.; Hsiao, B.S. Nanocellulose-enabled membranes for water purification: Perspectives. Adv Sustain Syst 2020, 4, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Syamani, F.A. Cellulose-based membrane for adsorption of dye in batik industry wastewater. Int J Hydro 2020, 4(6), 281-283. [CrossRef]

- Ebnesajjad, S. Introduction to fluoropolymers: materials, technology, and applications. W. Andrew, Ed., 2020.

- Zhu, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J. Preparation and properties of PTFE hollow fiber membranes for desalination through vacuum membrane distillation. J Membr Sci 2013, 446, 145-153. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.H.; El-Naas, M-H.; Zhang, Z. Van der Bruggen, B. CO2 capture using hollow fiber membranes: a review of membrane wetting. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 963-978. [CrossRef]

- Saffarini, R.B.; Mansoor, B.; Thomas, R.; Arafat, H.A. Effect of temperature-dependent microstructure evolution on pore wetting in PTFE membranes under membrane distillation conditions. J Membr Sci 2013, 429, 282-294. [CrossRef]

- Pizzichetti, A.R.; Pablos, C.; Álvarez-Fernández, C.; Reynolds, K.; Stanley, S.; Marugán, J. Evaluation of membranes performance for microplastic removal in a simple and low-cost filtration system. Case Stud Chem Environ Eng., 2020, 3. [CrossRef]

- Kayvani Fard, A.; McKay, G.; Buekenhoudt, A.; Al Sulaiti, H.; Motmans, F.; Khraisheh, M.; Atieh, M. Inorganic Membranes: Preparation and Application for Water Treatment and Desalination. Materials (Basel). 2018, 11(1), 74. [CrossRef]

- Hofs, B.; Ogier, J.; Vries, D.; Beerendonk, F.; Cornelissen, E.R. Comparison of ceramic and polymeric membrane permeability and fouling using surface water. Sep Purif Technol 2011, 79, 365-374. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Lyu, Z.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. Ceramic-based membranes for water and wastewater treatment. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2019, 578, 123513. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Xiao, P.; Li, J.; Tian, E.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, Y. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp 2016, 508, 327–335.

- Fathurrahman, A.; Arisandi, R.; Fahrina, A.; Arahman, N.; Razi, F. Filtration performance of polyethersulfone (PES) composite membrane incorporated with organic and inorganic additives. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng 2021. [CrossRef]

- Arahman, N.; Mulyati, S.; Fahrina, A.; Muchtar, S.; Yusuf, M.; Takagi, R.; Matsuyama, H.; Nordin, N.A.H.; Bilad, M.R. Improving Water Permeability of Hydrophilic PVDF Membrane Prepared via Blending with Organic and Inorganic Additives for Humic Acid Separation. Molecules 2019, 24(22), 4099. [CrossRef]

- Moradihamedani, P.J.P.B. Recent advances in dye removal from wastewater by membrane technology: a review. Polymer Bulletin 2022, 79(4), 2603-2631. [CrossRef]

- Pivokonsky, M.; Cermakova, L.; Novotna, K.; Peer, P.; Cajthaml, T.; Janda V. Occurrence of microplastics in raw and treated drinking water. Sci Total Environ 2018, 643:1644-1651. [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.F.; Zablouk, MA, Abid-Alameer AM. Experimental study of dye removal from industrial wastewater by membrane technologies of reverse osmosis and nanofiltration. Iranian J Environ Health Sci Eng 2012, 9(1),17. [CrossRef]

- Kankanige, D.; Babel, S. Contamination by 6.5 μm-sized microplastics and their removability in a conventional water treatment plant (WTP) in Thailand. J Water Process Eng 2021, 40, 101765. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Zeng, Z.; Wen, X.; Ren, X.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, R. Presence of microplastics in drinking water from freshwater sources: the investigation in Changsha, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021, 28(31), 42313-42324. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, H.; Movahedian Attar, H. Identification, quantification, and evaluation of microplastics removal efficiency in a water treatment plant (a case study in Iran) Air. Soil Water Res 2022, 15, 11786221221134945. [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Pan, Z.; Wang, W.; Ren, J.; Yu, X.; Lin, L.; Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Jin, X. Microplastic abundance, characteristics, and removal in wastewater treatment plants in a coastal city of China. Water Res 2019, 155, 255-265. [CrossRef]

- Tadsuwan, K.; Babel, S. Microplastic contamination in a conventional wastewater treatment plant in Thailand. Waste Manag Res 2021, 39(5), 754-761. [CrossRef]

- Reneker, D.H.; Chun, I. Nanometre diameter fibres of polymer, produced by electrospinning. Nanotechnology 1996, 7, 3, 216. [CrossRef]

- Acarer, S. A Review of Microplastic Removal from Water and Wastewater by Membrane Technologies. Water Sci Technol 2023, 88(1), 199. [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, B.K.; Pramanik, S.K.; Monira, S. Understanding the Fragmentation of Microplastics into Nanoplastics and Removal of Nano/Microplastics from Wastewater Using Membrane, Air Flotation and Nano-Ferrofluid Processes. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131053. [CrossRef]

- Marsano, B.D.; Yuniarto, A.; Purnomo, A.; Soedjo, E.S. Comparison Performances of Microfiltration and Rapid Sand Filter Operated in Water Treatment Plant. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1111, 012048. [CrossRef]

- Luogo, B.D.; Salim, T.; Zhang, W.; Hartmann, N. Reuse of Water in Laundry Applications with Micro- and Ultrafiltration Ceramic Membrane. Membranes 2022, 12(223). [CrossRef]

- Bitter, H.; Krause, L.; Kirchen, F.; Fundneider, T. Semi-Crystalline Microplastics in Wastewater Plant Effluents and Removal Efficiencies of Post-Treatment Filtration Systems. Water Res X 2022, 17, 100156. [CrossRef]

- Yahyanezhad, N.; Bardi, M.J.; Aminirad, H. An Evaluation of Microplastics Fate in the Wastewater Treatment Plants: Frequency and Removal of Microplastics by Microfiltration Membrane. Water Pract Technol 2021, 16(3), 782–792. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Su, Y.; Zhu, J.; Shi, J.; Huang, H.; Xie, B. Distribution and Removal Characteristics of Microplastics in Different Processes of the Leachate Treatment System. Waste Manag 2021, 120, 240–247. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Xue, W.; Hu, C.; Liu, H.; Qu, J.; Li, L. Characteristics of Microplastic Removal via Coagulation and Ultrafiltration during Drinking Water Treatment. Chem Eng J 2019, 359, 159–167. [CrossRef]

- Tadsuwan, K.; Babel, S. Microplastic Abundance and Removal via an Ultrafiltration System Coupled to a Conventional Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant in Thailand. J Environ Chem Eng 2022, 10(2), 107142. [CrossRef]

- Kara, N.; Sari Erkan, H.; Onkal Engin, G. Characterization and Removal of Microplastics in Landfill Leachate Treatment Plants in Istanbul, Turkey. Anal Lett 2023, 56(9), 1535–1548. [CrossRef]

- Barbier, J.S.; Dris, R.; Lecarpentier, C.; Raymond, V.; Delabre, K.; Thibert, S.; Tassin, B. Microplastic Occurrence after Conventional and Nanofiltration Processes at Drinking Water Treatment Plants: Preliminary Results. Front Water 2022, 4, 886703. [CrossRef]

- Dalmau-Soler, J.; Ballesteros-Cano, R.; Boleda, M.R.; Paraira, M.; Ferrer, N.; Lacorte, S. Microplastics from Headwaters to Tap Water: Occurrence and Removal in a Drinking Water Treatment Plant in Barcelona Metropolitan Area (Catalonia, NE Spain). Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 59462–59472. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhu, Z.R.; Li, W.R.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.K.; Zhang, L.; Jin, J.; Dai, X.; Ni, B. Revisiting Microplastics in Landfill Leachate: Unnoticed Tiny Microplastics and Their Fate in Treatment Works. Water Res 2021, 190, 116784. [CrossRef]

- Ziajahromi, S.; Neale, P.A.; Rintoul, L.; Leusch, F.D. Wastewater Treatment Plants as a Pathway for Microplastics: Development of a New Approach to Sample Wastewater-Based Microplastics. Water Res 2017, 112, 93–99. [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, G.; Corsino, S.F.; De Marines, F.; Lopresti, F.; La Carrubba, V.; Torregrossa, M.; Viviani, G. Occurrence of Microplastics in Waste Sludge of Wastewater Treatment Plants: Comparison between Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) and Conventional Activated Sludge (CAS) Technologies. Membranes 2022, 12(371). [CrossRef]

- Moslehyani, A.; Ismail, A.F.; Matsuura, T.; Rahma, M.; Goh, P.S. Recent Progresses of Ultrafiltration (UF) Membranes and Processes in Water Treatment. In Membrane Separation and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 85–110.

- Jacquet, N.; Wurtzer, S.; Darracq, G.; Wyart, Y.; Moulin, L.; Moulin, P. Effect of Concentration on Virus Removal for Ultrafiltration Membrane in Drinking Water Production. J Membr Sci, 2021, 634, 119417. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Mozia, S. Removal of Organic Matter from Water by PAC/UF System. Water Res 2002, 36(16), 4137–4143. [CrossRef]

- Muthumareeswaran, M.; Alhoshan, M.; Agarwal, G. Ultrafiltration Membrane for Effective Removal of Chromium Ions from Potable Water. Sci Rep 2017, 7(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Korus, I.; Loska, K.J. Removal of Cr(III) and Cr(VI) Ions from Aqueous Solutions by Means of Polyelectrolyte-Enhanced Ultrafiltration. Desalination 2009, 247(1–3), 390–395. [CrossRef]

- Puthai, W.; Kanezashi, M.; Nagasawa, H.; Tsuru, T. Development and Permeation Properties of SiO2–ZrO2 Nanofiltration Membranes with a MWCO of <200. J Membr Sci, 2017, 535, 331–341. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Jang, J.; Kim, S.; Lim, J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, I.S. PIP/TMC Interfacial Polymerization with Electrospray: Novel Loose Nanofiltration Membrane for Dye Wastewater Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 36148–36158. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fatah, M.A. Nanofiltration Systems and Applications in Wastewater Treatment: Review Article. Ain Shams Eng J 2018, 9(4), 3077–3092. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Hadadian, Z.; Moradi, M.; Haghighi, A.; Mujtaba, I.M. Performance Evaluation of a Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis Pilot-Plant Desalination Process under Different Operating Conditions: Experimental Study. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100134. [CrossRef]

- Indika, S.; Wei, Y.; Hu, D.; Ketharani, J.; Ritigala, T.; Cooray, T.; Hansima, M.A.; Makehelwala, M.; Jinadasa, K.B.; Weragoda, S.K.; Weerasooriya, R. Evaluation of Performance of Existing RO Drinking Water Stations in the North Central Province, Sri Lanka. Membranes 2021, 11(383). [CrossRef]

- Peters, T. Membrane Technology for Water Treatment. Chem. Eng. Technol 2010, 33(8), 1233–1240. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wu, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C. Fate of Microplastics in a Coastal Wastewater Treatment Plant: Microfibers Could Partially Break through the Integrated Membrane System. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2022, 16(7), 96. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Islam, N.; Tasannum, N.; Mehjabin, A.; Momtahin, A.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Mofijur, M. Microplastic Removal and Management Strategies for Wastewater Treatment Plants. Chemosphere 2024, 347, 140648. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Wibowo, A.; Karim, Z.; Posoknistakul, P.; Matsagar, B.; Wu, K.C.; Sakdaronnarong, C. Wastewater Treatment Using Membrane Bioreactor Technologies: Removal of Phenolic Contaminants from Oil and Coal Refineries and Pharmaceutical Industries. Polymers, 2024, 16(3), 443. [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.S.; Tahir, I.; Ali, A.; Ayub, I.; Nasir, A.; Abbas, N.; Hamid, K. Innovative Technologies for Removal of Microplastic: A Review of Recent Advances. Heliyon, 2024, 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, M.-K.; Truong, Q.-M.; Thai, V.-A.; Pham, M.-T.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D. Microplastics and Pharmaceuticals from Water and Wastewater: Occurrence, Impacts, and Membrane Bioreactor-Based Removal. Sep Purif Technol, 2025, 361(3), 131489. [CrossRef]

- Beygmohammdi, F.; Nourizadeh Kazerouni, H.; Jafarzadeh, Y.; Hazrati, H.; Yegani, R. Preparation and Characterization of PVDF/PVP-GO Membranes to Be Used in MBR System. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 154, 232–240. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Q. Membrane Fouling Mechanism of HTR-PVDF and HMR-PVDF Hollow Fiber Membranes in MBR System. Water, 2022, 14(16), 2576. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; López-Grimau, V.; Vilaseca, M.; Crespi, M. Treatment of Textile Wastewater by CAS, MBR, and MBBR: A Comparative Study from Technical, Economic, and Environmental Perspectives. Water, 2020, 12(5), 1306. [CrossRef]

- Barreto, C.M.; Garcia, H.A.; Hooijmans, C.M.; Herrera, A.; Brdjanovic, D. Assessing the Performance of an MBR Operated at High Biomass Concentrations. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 2017, 119, 528–537. [CrossRef]

- Prasertkulsak, S.; Chiemchaisri, C.; Chiemchaisri, W.; Yamamoto, K. Removals of Pharmaceutical Compounds at Different Sludge Particle Size Fractions in Membrane Bioreactors Operated under Different Solid Retention Times. J Hazard Mater 2019, 368, 124–132. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.U.; Roy, H.; Islam, M.R.; Tahmid, M.; Fariha, A.; Mazumder, A.; Tasnim, N.; Pervez, M.N.; Cai, Y.; Naddeo, V.; Islam, M.S. The Advancement in Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) Technology toward Sustainable Industrial Wastewater Management. Membranes 2023, 13, 181. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Grasmick, A. Organic Matter Recovery from Municipal Wastewater by Using Dynamic Membrane Separation Process. Chem Eng J 2013, 219, 190–199. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, S.; He, F.; Xu, D.; Kong, L.; Wu, Z. Phosphate Removal of Acid Wastewater from High-Phosphate Hematite Pickling Process by In-Situ Self-Formed Dynamic Membrane Technology. Desalin Water Treat 2012, 37, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Ma, Z.; Yang, Q. Formation and Performance of Kaolin/MnO2 Bi-Layer Composite Dynamic Membrane for Oily Wastewater Treatment: Effect of Solution Conditions. Desalination 2011, 270, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Jiang, B.; Qiu, X.; Gao, B. A Hybrid System Combining Self-Forming Dynamic Membrane Bioreactor with Coagulation Process for Advanced Treatment of Bleaching Effluent from Straw Pulping Process. Water Treat 2012, 18(2), 212–216. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, B.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, B.; Liu, H. Improving Volatile Fatty Acid Yield from Sludge Anaerobic Fermentation through Self-Forming Dynamic Membrane Separation. Bioresour Technol 2016, 218, 92–100.. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Alibardi, L.; Cossu, R.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; Spagni, A. Analysis of Fouling Development under Dynamic Membrane Filtration Operation. Chem Eng J 2017, 312, 136–143. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, G.; Yu, H.; Xing, J. Dynamic Membrane for Micro-Particle Removal in Wastewater Treatment: Performance and Influencing Factors. Sci. Total Environ 2018, 627, 332–340. [CrossRef]

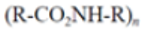

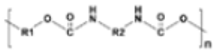

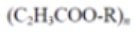

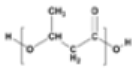

| Categories | Molecular formula | Chemical structure | Common applications |

Specific Density (g/cm3) |

Recycle symbol |

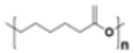

| Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) |  |

|

Beverage bottles | 1.34–1.39 |  |

| High-density polyethylene (HDPE) |  |

|

Containers for milk, motor oil, shampoos and conditioners, soap bottles, detergents, and bleaches | 0.933–1.27 |  |

|

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) |

|

|

Bags, tubes | 1.16–1.30 |  |

| Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) |  |

|

Plastic bags, six-pack rings, bottles | 0.91–0.93 |  |

|

Polypropylene (PP) |

|

|

Rope, bottle caps, netting | 0.90–0.92 |  |

|

Polystyrene (PS) |

|

|

Cups, buoy Plastic utensils, food containers, packaging | 0.01–1.05 1.04–1.09 |

|

|

Policarbonate (PC) |

|

|

Electronic compounds | 1.20–1.22 |  |

|

Polyurethane (PU) |

|

|

Bedding, automotive and truck seating | 0.11-0.04 | |

|

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) |

|

|

Packaging, medicine or agriculture. | 1.0-1.3 | |

|

Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) |

|

|

Applications in medical sector, packaging industries, nanotechnology and agriculture. | 1.18 -1.26 | |

|

Polylactic acid (PLA) |

|

|

Medical implants, food packaging and fibers for clothing. | 1.27 | |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) |

|

|

Packaging, scaffolds, prosthetics, sutures, drug delivery, films, carry bags | 1.145 | |

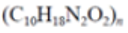

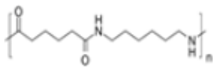

| Polyamide (PA) |

|

|

Ropes | 1.13–1.15 | |

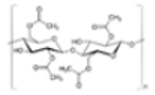

| Cellulose Acetate (CA) |

(C10H16O8)n |  |

Filter cigarettes | 1.22–1.24 | |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) |

(C2F4)n |  |

Teflon items, tubes | 2.10–2.30 |

| Substances | Marine biota | References |

| Microplastics | Phytoplankton | [116] |

| Microplastics and phthalates | Planktons | [117,118] |

| Microplastics | Gastropods | [119] |

| Microplastics | Oysters and mussels | [120,121] |

| Microplastics | Crab | [122,123] |

| Microplastic | Norway lobster | [124] |

| Plastics/ Microplastics | Fish | [125,126,127,128] |

| Plastics | Turtles | [129,130] |

| Phthalates | Whale | [118] |

| Plastic | Whale | [131] |

| Plastic-derived substances (brominated congeners e.g., PBDEs) | Seabirds | [132] |

| PDMS, silicones | Seabirds | [133] |

| Microplastics | Humans (Placenta ex vivo) |

[134] |

| Microplastics | Humans (Airway smooth muscle cell) |

[135] |

| Microplastics | Humans (Endothelial cells—blood vessels) |

[136] |

| Adverse effects | Organisms / Class of Organisms | References |

| Alterations in photosynthesis, oxidative stress. | Algae—Chlorella and Scenedesmus | [116] |

| Negative impact on health. | Zooplankton | [137] |

| Alterations in embryonic development. | Sea urchin—Lytechinus variegatus | [138] |

| Bioaccumulation of chemical pollutants from plastic and hepatic stress. | Fish—Oryzias latipes | [100] |

| Reduction of the stomach space, leading gradually to starvation. | Birds and marine biota | [139] |

| Clog digestive paths and cause injuries and infections that could result in death. | Marine worms | [93,132,140,141] |

| Hindered acetylcholinesterase enzymatic activity (potential issues in seafood safety as this effect has been linked to Alzheimer’s disease in humans). | Marine biota | [142,143,144] |

| Alterations on endocrine disruption (Ingestion of plastic with plastic-derived compounds or sorbed from the ambient environment such as PBDEs). | Marine organisms’ tissues | [115,132,145] |

| Alterations on the hormonal system. (Bisphenol-A) | Fish and other marine organisms | [146] |

| Growth rate reduction, reproductive failure. | Fish and other marine organisms | [147] |

| Translocation out of the digestive system pancreas, liver or gill. | Bivalve and fish | [122,148] |

| Developmental abnormalities in embryos as well as interference in reproduction. | Fish | [149] |

| Membrane Type | Reverse Osmose | Nanofiltration | Ultrafiltration | Microfiltration |

| Membrane | Assimetric | Assimetric | Assimetric | Simetric Assimetric |

| Porosity | < 0.002 μm | < 0.002 μm | 0.2–0.02 μm | 4–0.02 μm |

| Membrane material | Cellulose Acetate, Thin film |

Cellulose Acetate, Thin film |

Ceramic Material, Polysulfone, Polyvinylidene Fluoride, Cellulose Acetate, Thin film |

Ceramic material, Polysulfone, Polyvinylidene Fluoride |

| Membrane module | Tubular, espiral, plane-and-frame |

Tubular, spiral, plane-and-frame |

Tubular, hollow fiber, spiral, plane-and-frame |

Tubular, hollow fiber |

| Operational pressure |

15–150 bar | 5–35 bar | 3–10 bar | ˂ 2 bar |

| Retained Material | High molecular weight components (e.g., proteins) sodium chloride, glucose and aminoacids |

High molecular weight components (e.g., proteins), mono- and bivalent ions, oligosaccharides and negative polyvalent ions |

Virus, polysaccharides proteins and macromolecules |

Clay particles and bacteria |

| Filtration membrane |

Treatment plant Type/Location |

Membrane characteristics | MP abundance in effluent (MP/L) |

Removal efficiency (%) |

References |

| MF | Laboratory | Material: PVDF and Pore size 0.1 μm | - | Up to 91 | [203] |

| MF | Laboratory | Material: PC and Pore size: 5 μm Material: CA and Pore size: 5 μm Material: PTFE and Pore size: 5 μm |

33 000–127 000 8 000–27 000 46 000–47 000 |

96.8–99.6 a 94.3–99.8 a 96–99.6 a |

[186] |

| MF | WTP /Indonesia | Pore size: 0.05 μm | 5 | 81.5 | [204] |

| MF | Laboratory | Material: SiC support and SiC membrane, maximum pore size: 604 nm | 1,250 | 98,5 | [205] |

| MF | WWTP/ Germany | Pore size: 0.1 μm | 0.67 μg/L | ˃ 94 | [206] |

| UF | WWTP/ Iran | Material: PVDF and PET, Pore size: 0.1 μm | 0–2 | 98.1-100 | [207] |

| UF | Laboratory | Material: PES, MWCO: 100 kDa | - | Up to 96 | [203] |

| UF | LLTP/ China | - | ~ 0.1 | 75 | [208] |

| UF | Laboratory | Material: SiC support and ZrO2 membrane, maximum pore size: 74 nm | 450 | 99.2 | [205] |

| UF | WTP/ Indonesia | Pore size: 0,07 μm | 22 | 37.1 | [204] |

| UF | Laboratory | Material: PVDF, Pore size: 30 nm, module: flat sheet | 0 | 100 | [209] |

| UF | WWTP/Thailand | Material: PES/PVP blend, pore size: 0,1 μm | 2,33 | 78,16 | [210] |

| UF | LLTP/ Turkey | - | 6,5 | 96 |

[211] |

| NF | LLTP/ Turkey | - | ~ 10 2 |

96 99 |

[211] |

| NF | DWTP/ France | Material: poly piperazine-amide and PSF MWCO: 400 Da, Pore size: 0,1 nm | 0–0.018 | - | [212] |

| RO | DWTP/ Spain | - | 0.06 | 54 ± 27 | [213] |

| RO | LLTP/ China | Pore size: 0.1 nm | 0.4 | ~ 99.8 | [214] |

| RO | WWTP/ Australia | - | 0.21 | - | [215] |

| MBR sludge | WWTP/ Italy | Pore size: 0.04 μm Module: hollow fiber submerged UF |

81.1 × 103 (MP/kg) |

- | [216] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).