Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

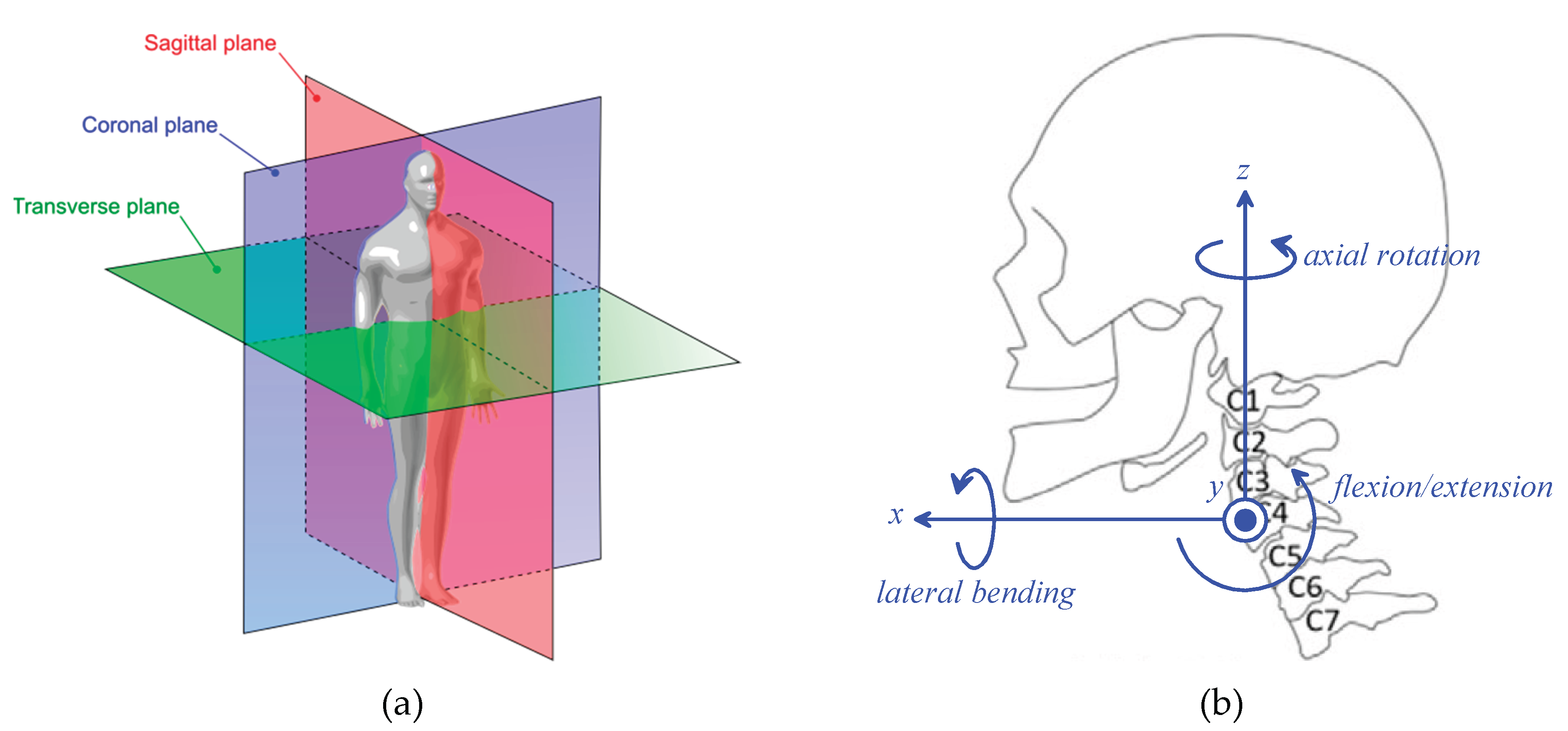

2.1. Summary of Neck Biomechanics and Identification of Neck Braces’ Requirements

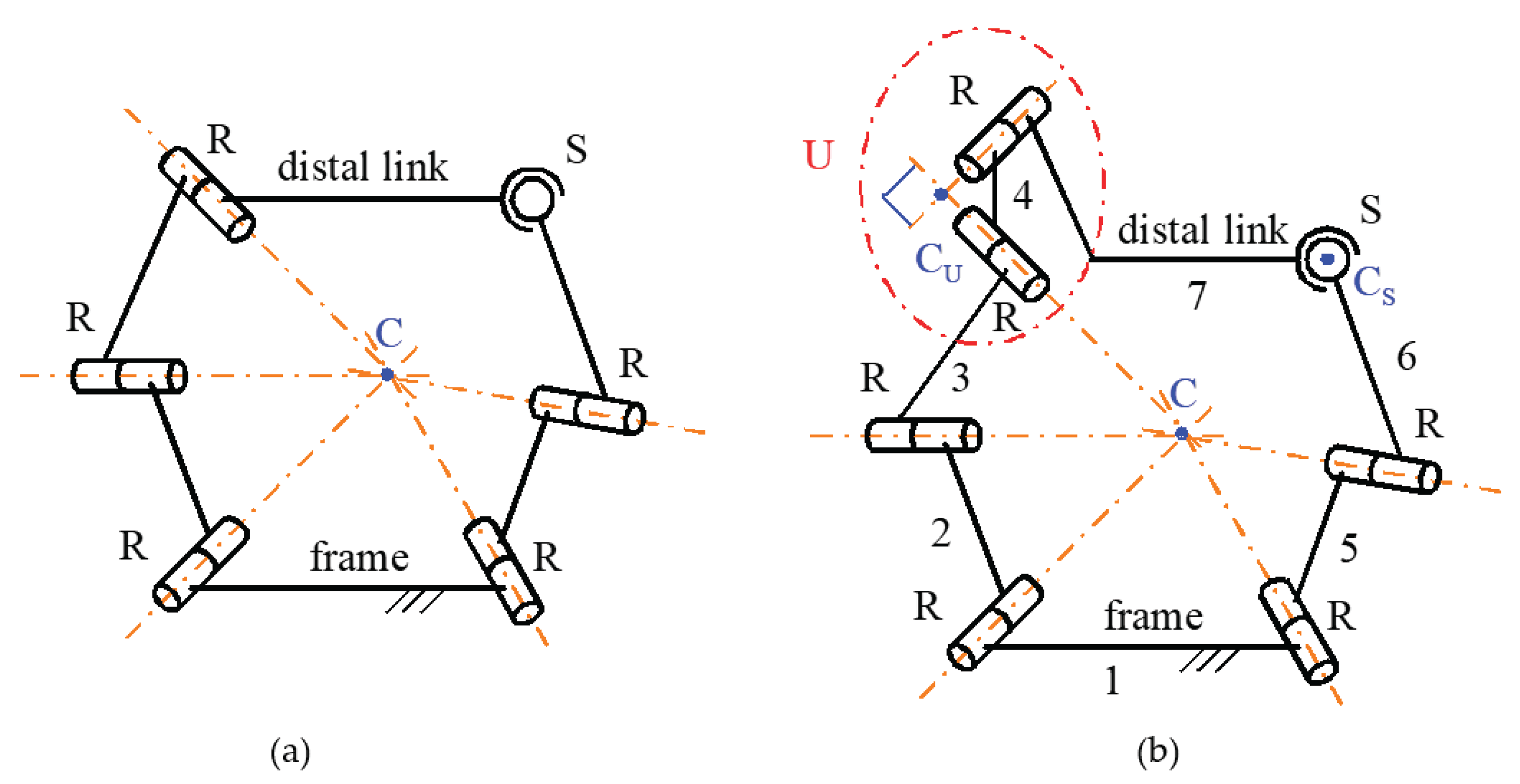

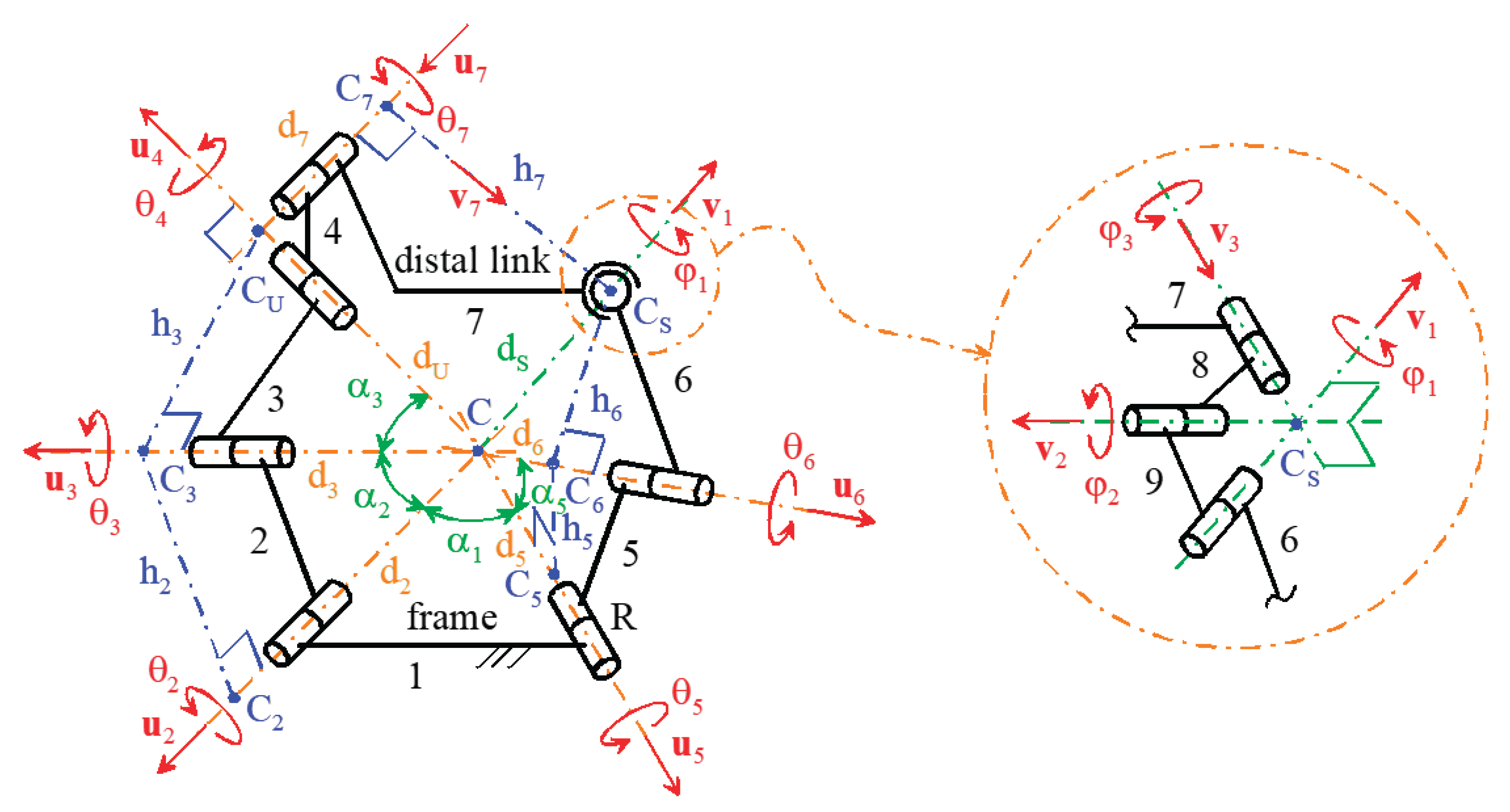

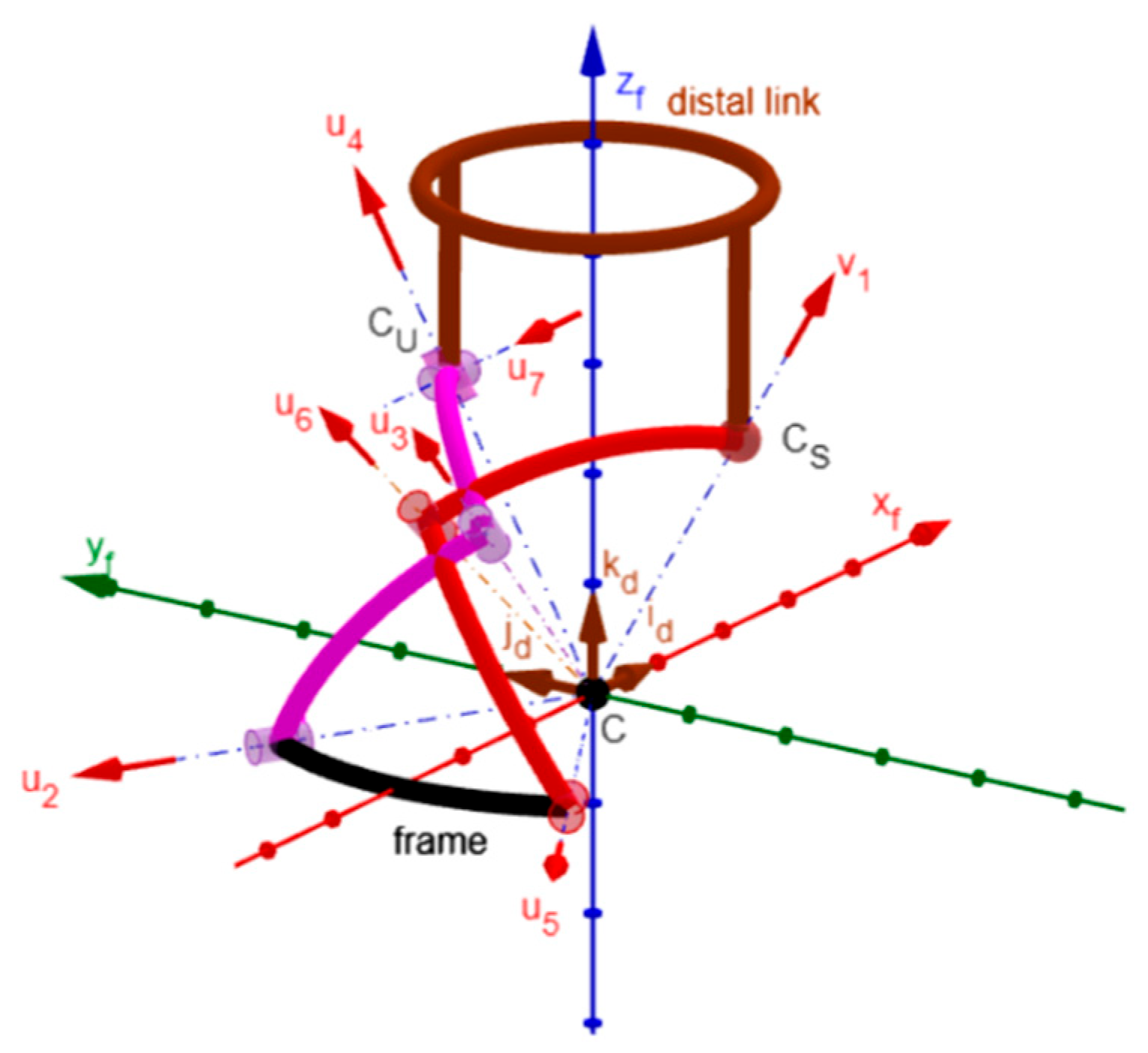

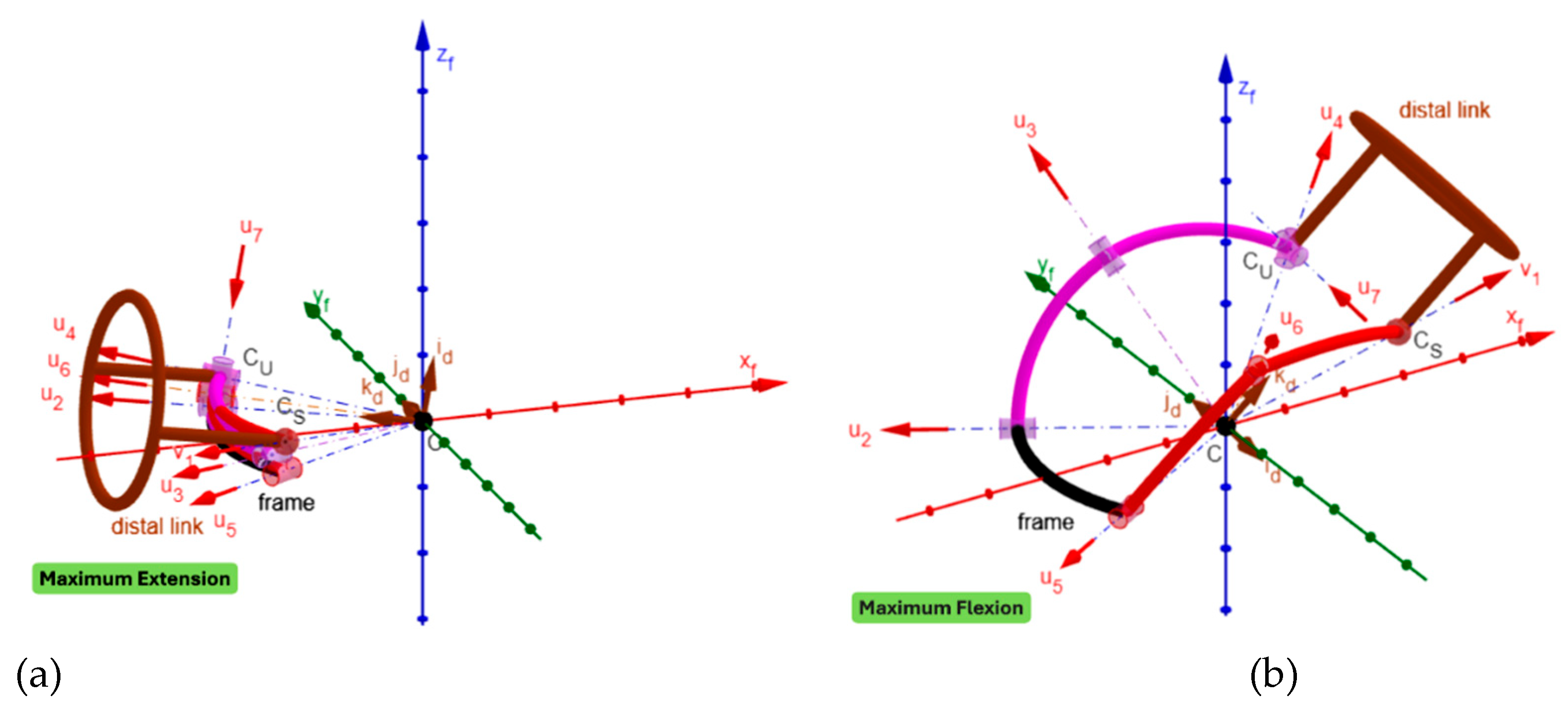

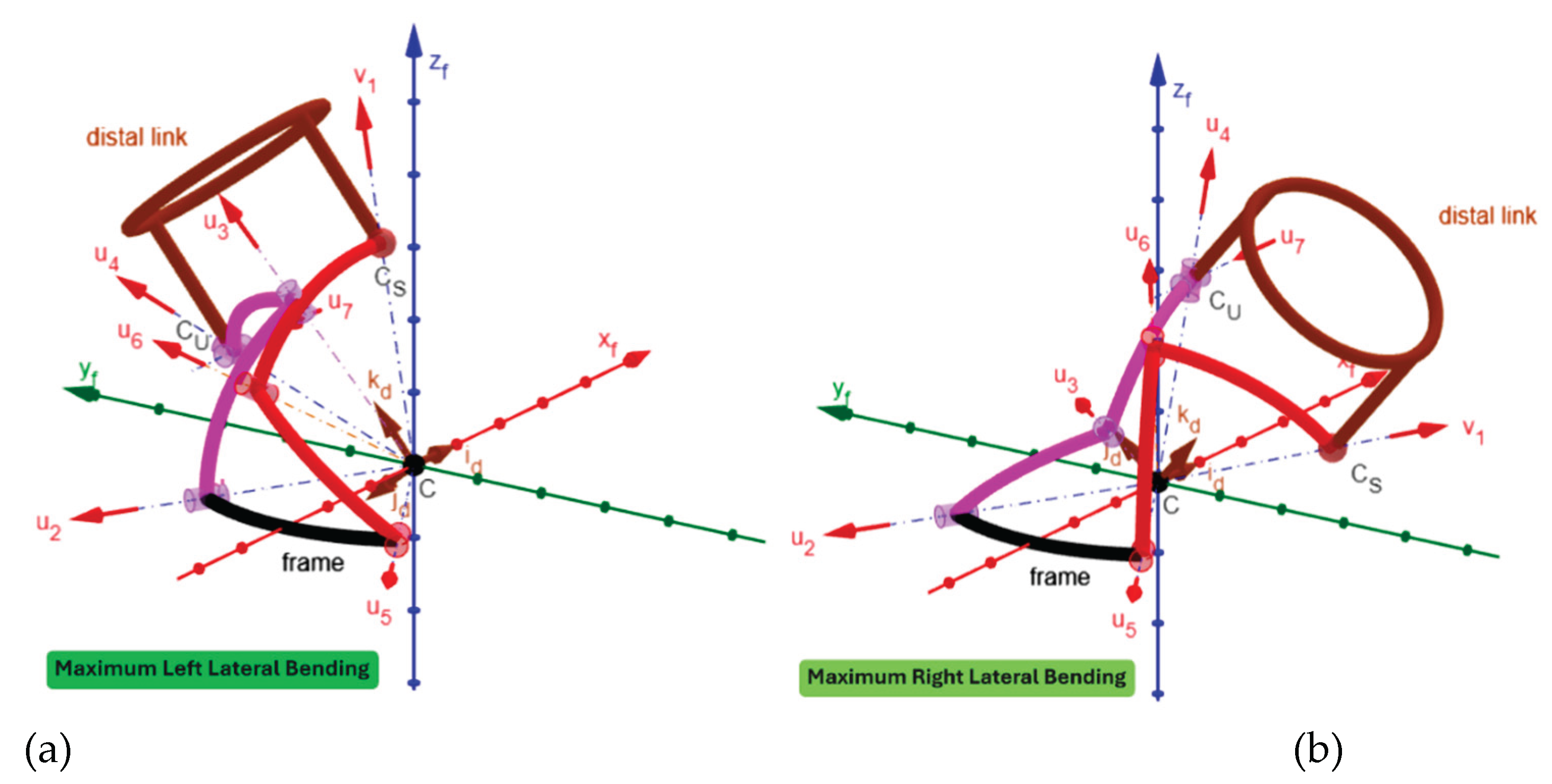

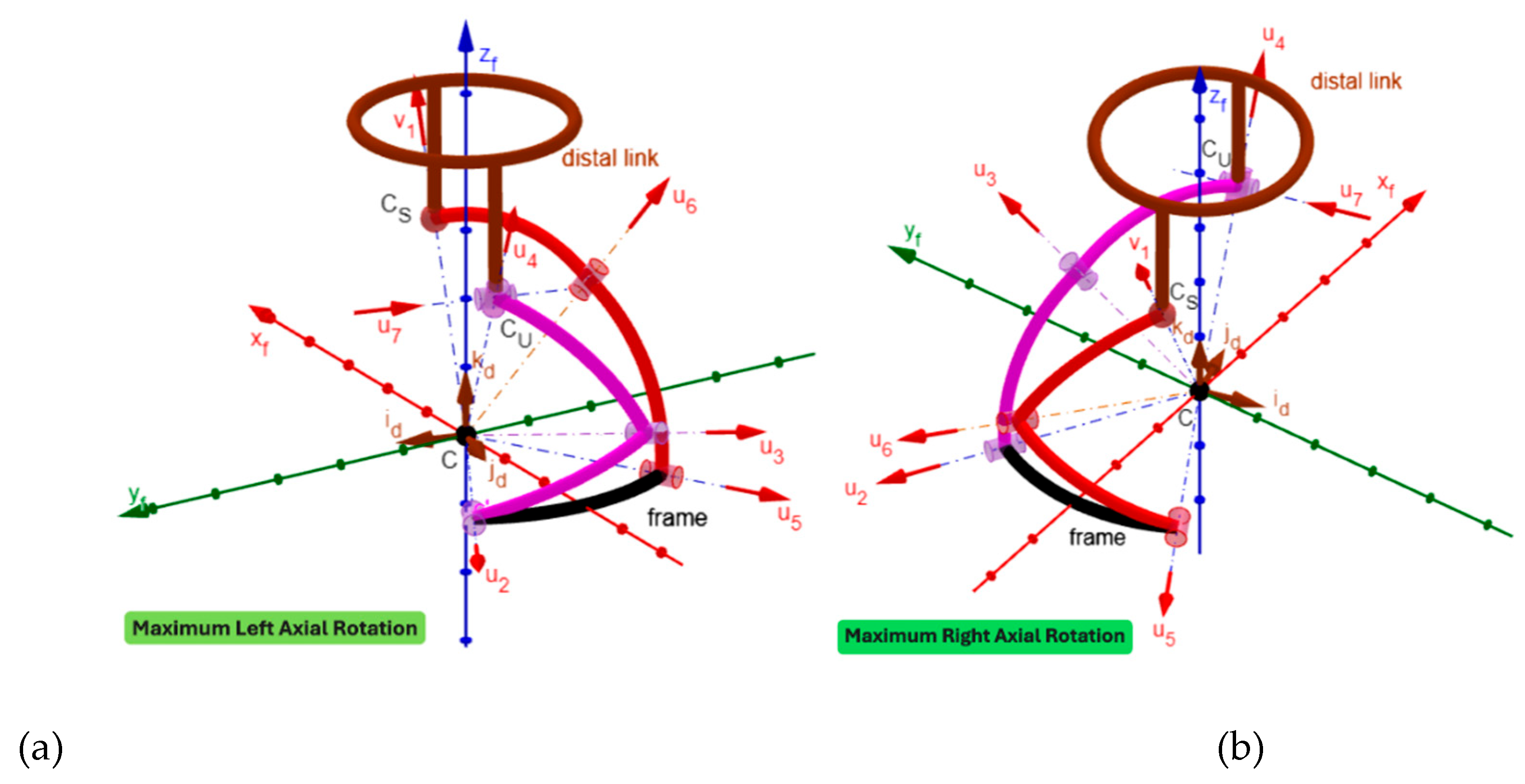

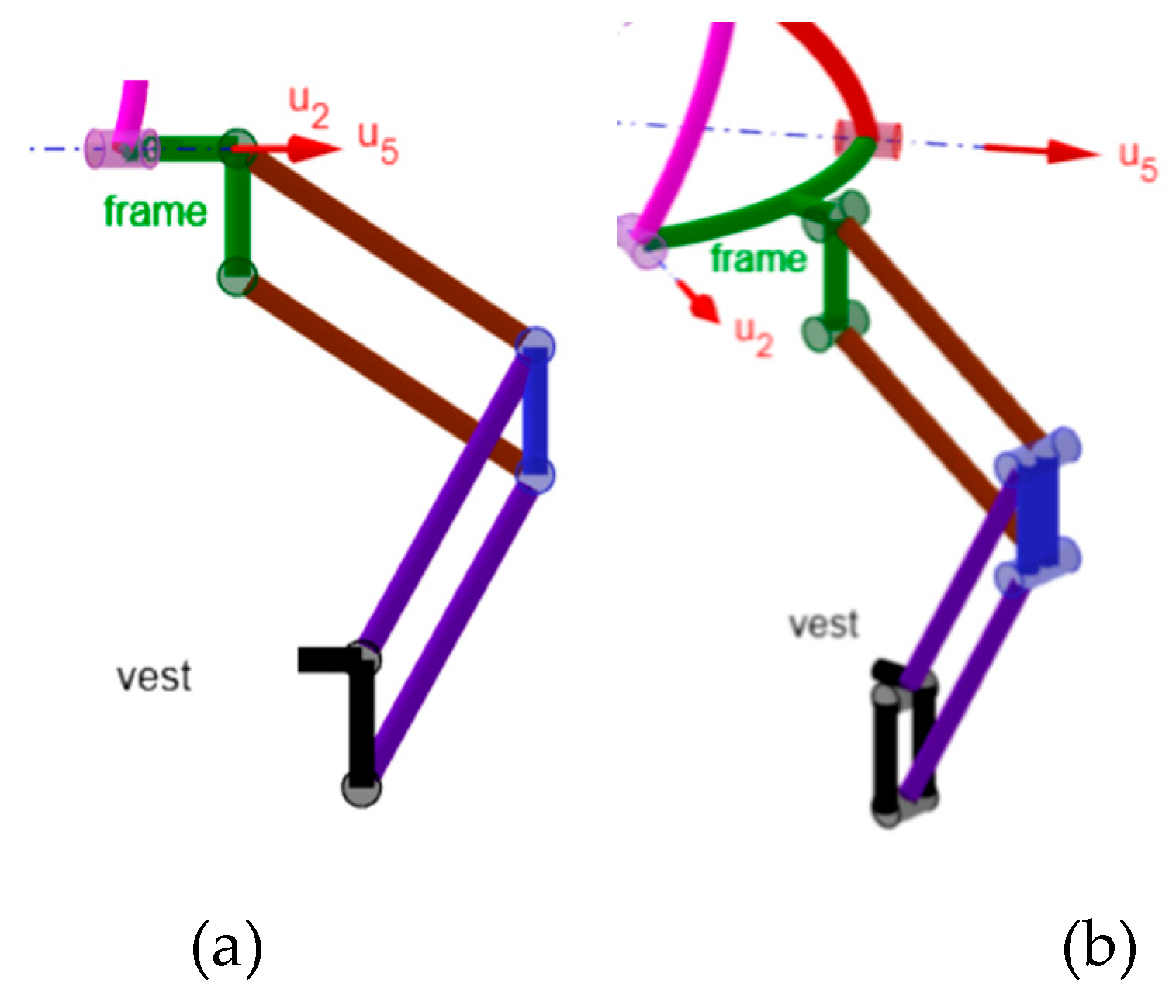

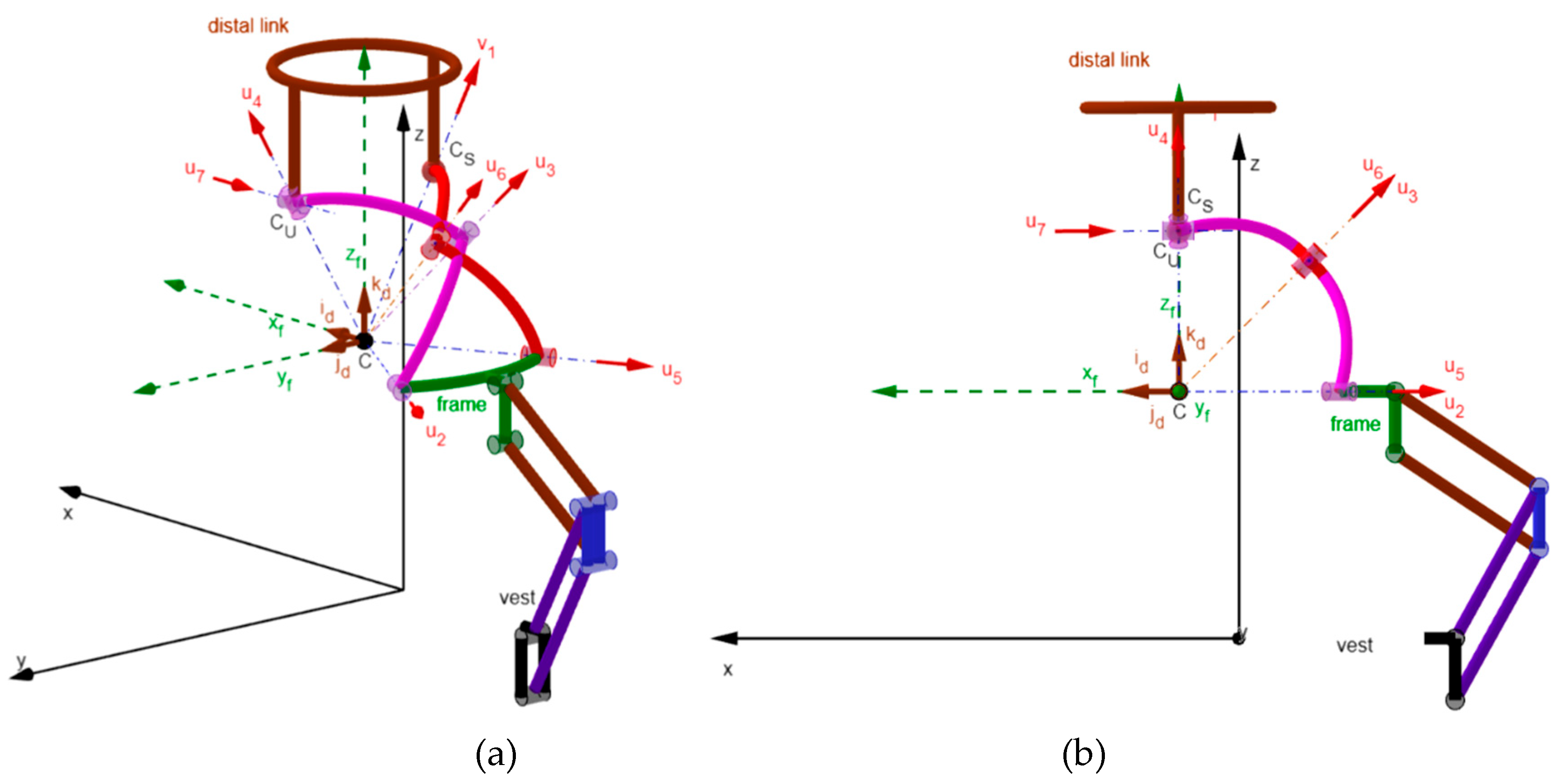

2.2. The RRU-RRS Mechanism

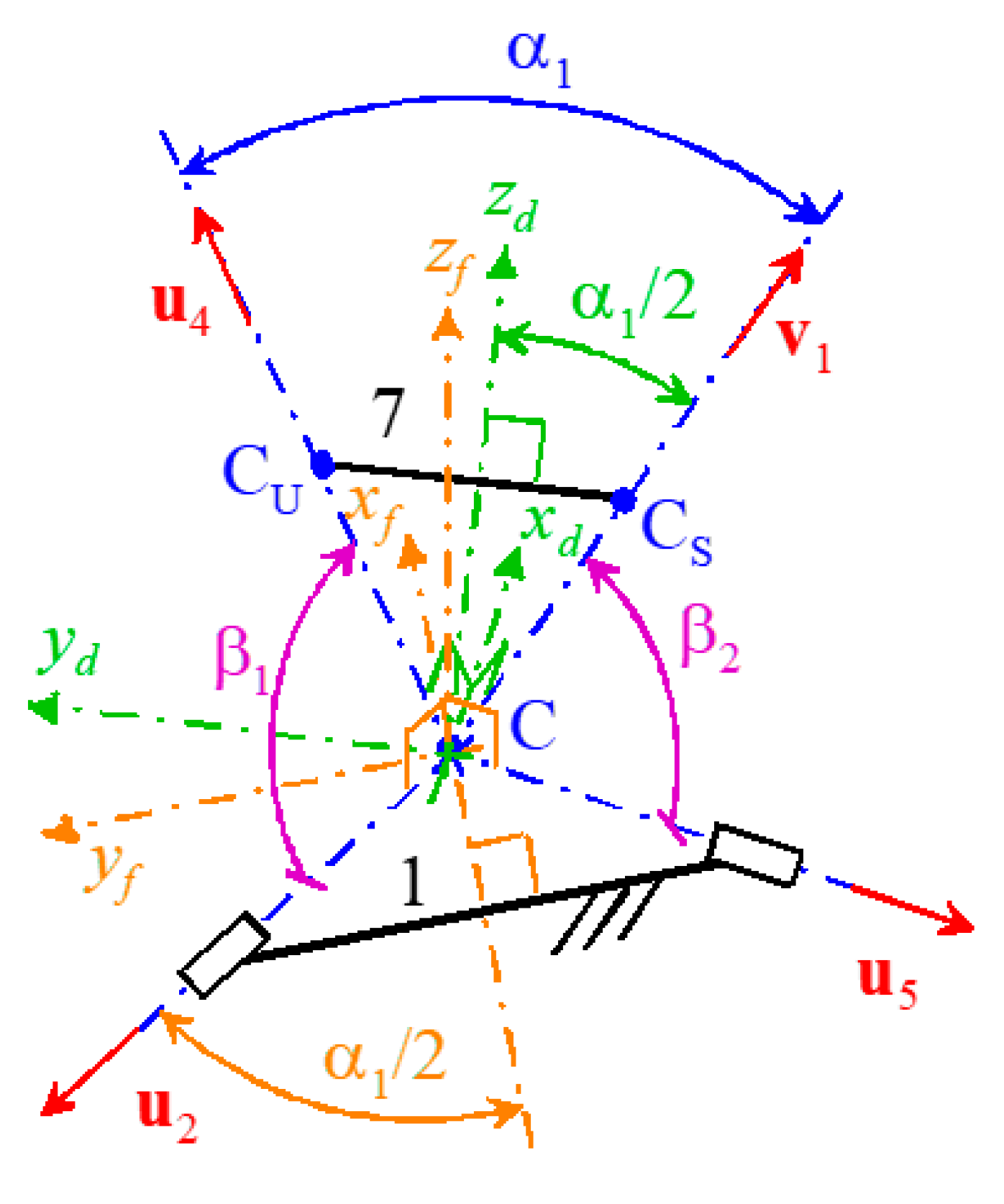

2.3. Position Analysis of the RRU-RRS Mechanism

2.3.1. Inverse Position Analysis (IPA)

2.3.2. Forward Position Analysis

2.4. Instantaneous Kinematics and Singularity Analysis of the RRU-RRS Mechanism

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| HNC | Head neck cancer |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| CSI | Cervical spine injury |

| C1, …, C7 | Vertebrae of the cervical spine (see Figure 1(b)) |

| O | Occipital bone |

| WAD | Wearable assistive device |

| SM | Serial mechanism |

| PM | Parallel mechanism |

| DOF | Degree of freedom |

| P | Prismatic pair or only the adjective “prismatic” |

| R | Revolute pair or only the adjective “revolute” |

| S | Spherical pair or only the adjective “spherical” |

| U | Universal joint |

| SMC | Spherical motion center |

| IPA | Inverse position analysis |

| FPA | Forward position analysis |

| IK | Instantaneous kinematics |

| IIK | Inverse instantaneous kinematics |

| FIK | Forward instantaneous kinematics |

| OW | Orientation workspace |

| IAR | Instantaneous axis of rotation |

| ISA | Instantaneous screw axis |

References

- Longinetti, Elisa; Fang, F. Epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an update of recent literature. Current Opinion in Neurology 2019, 32, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gormley, M.; Creaney, G.; Schache, A.; et al. Reviewing the epidemiology of head and neck cancer: definitions, trends and risk factors. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 233, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arockia, S.; Arockia, D; Lingampally, P. K.; Nguyen, G. M. T.; Schilberg, D. A comprehensive review of wearable assistive robotic devices used for head and neck rehabilitation. Results in Engineering 2023, 19, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prablek, M.; Gadot, R.; Xu, D. S.; Ropper, A. E. Neck Pain: Differential Diagnosis and Management. Neurol. Clin. 2023, 41, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Neck Pain Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neck pain, 1990-2020, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2024, 6, e142–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminasab, S.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Amiri, P.; et al. Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A. M.; Komar, A.; Ringash, J; et al. A scoping review of rehabilitation interventions for survivors of head and neck cancer. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 2093–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Agrawal, S. K. Kinematic Design of a Dynamic Brace for Measurement of Head/Neck Motion. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2017, 2, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B. C.; Zhang, H.; Long. S.; Obayemi, A.; Troob, S. H.; Agrawal, S. K. A novel neck brace to characterize neck mobility impairments following neck dissection in head and neck cancer patients. Wearable Technol. 2021, 2, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. M.; Hart, D. L.; Simmons, E. F.; Ramsby, G. R.; Southwick, W. O. Cervical orthoses. A study comparing their effectiveness in restricting cervical motion in normal subjects. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 1977, 59, 332–339. [Google Scholar]

- McKeon, J. F.; Alvarez, P. M.; Castaneda, D. M.; Emili, U.; Kirven, J.; Belmonte, A. D.; Singh, V. Cervical Collar Use Following Cervical Spine Surgery: A Systematic Review. JBJS Reviews 2024, 12, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Lai, C. Y.; Bab-Hadiashar, A. A Novel Design of Cable-Driven Neck Rehabilitation Robot (CarNeck). In: Procs. of 2019 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM), Hong Kong, China, 2019, pp. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M. N.; Tabasi, A.; Kingma, I; van Dieën, J. H. A novel passive neck orthosis for patients with degenerative muscle diseases: Development & evaluation. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2021, 57, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Li, P. A 6-DOF exoskeleton for head and neck motion assist with parallel manipulator and sEMG based control. In Procs. of 2016 International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Saint Julian's, Malta, 2016, pp. [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Ping, S.; Hongyu, Z.; Sujiao, L.; Fanfu, F.; Hongliu, Y. Design and kinematic analysis of cervical spine powered exoskeleton based on human biomechanics. Journal of University of Shanghai for Science and Technology 2022, 44, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingampally, P. K.; Selvakumar, A. A. Kinematic and Workspace Analysis of a Parallel Rehabilitation Device for Head-Neck Injured Patients. FME Transactions 2019, 47, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahem, M. E.-H.; El-Wakad, M. T.; El-Mohandes, M. S.; Sami, S. A. Implementation and Evaluation of a Dynamic Neck Brace Rehabilitation Device Prototype. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2022, 2022, 6887839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano, A.; Ballesteros, M.; Cruz-Ortiz, D.; Chairez, I. Active neck orthosis for musculoskeletal cervical disorders rehabilitation using a parallel mini-robotic device. Control Engineering Practice 2022, 128, 105312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J; Kulkarni, P. ; Zhao, X.; Agrawal S. K. Design of a traction neck brace with two degrees-of-freedom via a novel architecture of a spatial parallel mechanism. Robotica 2024, 42, 4136–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Z.; Gao, G. Design and Analysis of a Rigid-Flexible Parallel Mechanism for a Neck Brace. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2019, 2019, 9014653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, D. A. Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system: foundations for physical rehabilitation, 2nd ed.; Mosby (Elsevier): St. Louis, Missouri (US), 2010; ISBN 978-0-323-03989-5. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, U. K. Biomechanics of the Cervical Spine. In Handbook of Orthopaedic Trauma Implantology; Banerjee, A., Biberthaler, P., Shanmugasundaram, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1831–1852. ISBN 978-981-19-7539-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ouerfelli, M.; Kumar, V.; Harwin, W. S. Kinematic modeling of head-neck movements. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics - Part A: Systems and Humans 1999, 29, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penning, L. Normal movements of the cervical spine. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1978, 130, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, B.; Sihlbom, H.; Nordwall, A.; Malchau, H. Normal range of motion of the cervical spine. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1989, 70, 692–695. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, J.; Antinnes, J. A.; Panjabi, M.; Loustalot, D.; Bonomo, M. Age and Gender Related Normal Motion of the Cervical Spine. Spine 1992, 17, S393–S398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogduk, N.; Mercer, S. Biomechanics of the cervical spine I: Normal kinematics. Clin Biomech 2000, 15, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LibreTexts, Anatomy and Physiology (Boundless). LibreTexts project: Davis, CA (US), 2025. Available online: https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_ (accessed on day month year).

- Edmondston, S. J.; Henne, s.-E.; Loh, W.; Østvold, E. Influence of cranio-cervical posture on three-dimensional motion of the cervical spine. Manual Therapy 2005, 10, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, S.; Fuente, L. A.; Hayatleh, K.; Fellows, N.; Steil, J. J.; Crook, N. T. Design of a biologically inspired humanoid neck. In Procs. of 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Zhuhai, China, 2015, pp. -30. [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Arreguín, J.L.; Ceccarelli, M.; Torres-SanMiguel, C.R. Design of an Articulated Neck to Assess Impact Head-Neck Injuries. Life 2022, 12, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoomes-de Graaf, M.; Thoomes, E.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Cleland, J.A. Normative values of cervical range of motion for both children and adults: A systematic review. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2020, 49, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Fang, Y.; Guo, S.; Chen, Y. Design and kinematical performance analysis of a 3-RUS/RRR redundantly actuated parallel mechanism for ankle rehabilitation. ASME J. Mech. Robot. 2013, 5, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cempini, M.; De Rossi, S. M. M.; Lenzi, T.; Vitiello, N.; Carrozza, M. C. Self-alignment mechanisms for assistive wearable robots: A kinetostatic compatibility method. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2013, 29, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karouia, M.; Hervé, J.M. A Family of Novel Orientational 3-DOF Parallel Robots. In: Bianchi, G., Guinot, JC., Rzymkowski, C. (eds) Romansy 14. Series: International Centre for Mechanical Sciences (CISM), vol. 438. Springer: Vienna (AT), 2002. [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Gosselin, C. M. Type Synthesis of 3-DOF Spherical Parallel Manipulators Based on Screw Theory. ASME. J. Mech. Des. 2004, 126, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Gosselin, C. M. Type Synthesis of Parallel Mechanisms; Springer: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-3-540-71989-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zeng, G.; Lu, Y. The classification method of spherical single-loop mechanisms. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2012, 51, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogu, G. Structural Synthesis of Parallel Robots, Part 4: Other Topologies with Two and Three Degrees of Freedom; Springer: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-94-007-2674-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, J. Rational Kinematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-387-96813-1. [Google Scholar]

- Harary, F. Graph Theory; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1969; ISBN 9780201410334. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, K. Kinematic Geometry of Mechanisms; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 9780198562337. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gregorio, R. The 3-RRS Wrist: A New, Simple and Non-Overconstrained Spherical Parallel Manipulator. ASME J. Mech. Des. 2004, 126, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H; Chang, B. C.; Andrews, J.; Mitsumoto, H; Agrawal, S. K. A robotic neck brace to characterize head-neck motion and muscle electromyography in subjects with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol, 1671; 6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Albee, K.; Agrawal, S. K. A spring-loaded compliant neck brace with adjustable supports. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2018, 125, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Agrawal, S. K. An Active Neck Brace Controlled by a Joystick to Assist Head Motion. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2018, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.-C.; Zhang, H.; Trigili, E.; Agrawal, S. K. Bio-Inspired Gaze-Driven Robotic Neck Brace. In Procs of 2020 8th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference for Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), New York, NY, USA, 2020, pp. [CrossRef]

- Zlatanov, D.; Bonev, I. A.; Gosselin, C. M. Constraint Singularities as C-Space Singularities. In Advances in Robot Kinematics – Theory and Applications; Lenarčič, J., Thomas, F., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Nederlands, 2002; pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, C.M.; Angeles, J. Singularity analysis of closed-loop kinematic chains. IEEE Trans. Robot. Automat. 1990, 6, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, O.; Angeles, J. Architecture singularities of platform manipulators. In Procs. of the 1991 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Sacramento (CA, USA), 1991, pp. 1542–1547. [CrossRef]

- Zlatanov, D.; Fenton, R.G.; Benhabib, B. A unifying framework for classification and interpretation of mechanism singularities. ASME J. Mech. Des. 1995, 117, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venema, G. A. Exploring Advanced Euclidean Geometry with GeoGebra; Mathematical Association of America, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-61444-111-3. [Google Scholar]

- Söylemez, E. Kinematic Synthesis of Mechanisms: using Excel and GeoGebra; Springer: Cham, CH, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-30955-7. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gregorio, R.; Cinti, T. Geometric Constraint Programming (GCP) Implemented Through GeoGebra to Study/Design Planar Linkages. Machines 2024, 12, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, R.; Rico Martinez, J.M.; Dooner, D.B.; Cervantes-Sánchez, J.J.; García-Murillo, M.A. Construction of interactive kinematic spatial mechanism and robot models through GeoGebra software. Computer Applications in Engineering Education 2025, 33, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Cui, W.; Sang, D.-c.; Sang, H.-p.; Liu, B.-g. Clinical Relevance of Cervical Kinematic Quality Parameters in Planar Movement. Orthop Surg 2019, 11, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, R.; Demmelmaier, R.; Hacker, S. P.; Wilke, H.-J. Comparison of three-dimensional helical axes of the cervical spine between in vitro and in vivo testing. The Spine Journal 2018, 18, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Joint or Region | Flexion(+)/Extension(−) (Sagittal plane, (°)) |

Axial Rotation (Horizzontal plane, (°)) |

Lateral Bending (Coronal plane, (°)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-C1 joint | +5 / −10 | Negligible | About ±5 |

| C1-C2 joint | +5 / −10 | ± 35 ÷ 40 | Negligible |

| C2-C7 region | + 35 ÷ 40 / − 55 ÷ 60 | ± 30 ÷ 35 | ± 30 ÷ 35 |

| Total | + 45 ÷ 50 / − 75 ÷ 80 | ± 65 ÷ 75 | ± 35 ÷ 40 |

| Joint | Flexion(+)/Extension(−) (Sagittal plane, (°)) |

Axial Rotation (Horizzontal plane, (°)) |

Lateral Bending (Coronal plane, (°)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-C1 | +5 / −10 | Negligible | About ±1.5 |

| C1-C2 | +5 / −10 | ±41.5 | Negligible |

| C2-C3 | +4 / −8 | ±3 | ±7 |

| C3-C4 | +6 / −11 | ±6.5 | ±7 |

| C4-C5 | +7 / −12 | ±6.5 | ±7 |

| C5-C6 | +7 / −14 | ±6.5 | ±7 |

| C6-C7 | +8 / −15 | ±7 | ±7 |

| Total | + 42 / − 80 | ±71 | ±36.5 |

| Flexion(+)/Extension(−) (Sagittal plane, (°)) |

Axial Rotation (Horizzontal plane, (°)) |

Lateral Bending (Coronal plane, (°)) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ROM | + 50 / − 80 | ± 75 | ± 40 |

| Rotation | (ψ1, ψ2, ψ3) (°) |

β1 * (°) |

β2 * (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | (0, 50, 0) | 109 | 109 |

| Extension | (0,−80, 0) | 9 | 9 |

| Left Axial Rotation | (75, 0, 0) | 62 | 111 |

| Right Axial Rotation | (−75, 0, 0) | 111 | 62 |

| Right Lateral Bending | (0, 0, 40) | 95 | 62 |

| Left Lateral Bending | (0, 0, −40) | 62 | 95 |

| α1 (°) |

α2 (°) |

α3 (°) |

α5 (°) |

h6/dS | h7/dS | d7/dS | dU/dS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 0.829 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).