Introduction

Neurobiologically grounded treatments for mental illness including serotonergic and monoaminergic pharmacotherapies, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), and device-based neuromodulation interventions have advanced clinical care but remain insufficient for many patients with mood and affective disorders [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Abundant evidence indicates that religion and spirituality (R/S) are not merely socio-cultural constructs, but that they can illicit reproducible neurocognitive states with identifiable anatomical substrates, network dynamics, and biochemical signatures [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Studies investigating these mechanisms demonstrate how spiritual practices can modulate self-processing, emotion regulation, social connection, and stress physiology in manner that counteracts the core circuit dysfunctions of depression and anxiety [

11,

12,

13]. The objective of this review is therefore to synthesize current research on the neuroanatomy, neurochemistry, and psychophysiology of R/S to propose an integrated model for mental healthcare that moves beyond simple pathology-focused treatment toward a more comprehensive, resilience-oriented paradigm.

For the purposes of this review, the terms

religion and

spirituality require careful definition, as their meanings are complex and evolving. Religion is conceptualized as an organized system, often practiced within a community, that involves established theological traditions, sacred beliefs, divine power, and moral principles [

13]. Spirituality, in contrast, is often viewed as a more personal and individual search for sacred meaning and purpose, which may or may not be affiliated with religious practices [

14]. This differentiation pertains primarily to individuals identifying as "spiritual-but-not-religious" [

13]. Despite this distinction, research indicates that for many, the two concepts are deeply intertwined, with spirituality representing an expansion of religious life rather than a replacement [

14]. Clinically, R/S integrated psychotherapies adapt evidence-based modalities to patient worldviews by mobilizing psychosocial constructs such as hope, forgiveness, belonging, purpose, and altruism.

This paper will first delineate the distributed neural networks that form the anatomical basis of R/S practice and experience. It then examines the specific neurophysiological, neurochemical, and psychoneuroimmunological pathways that mediate these experiences and their impacts on health. Subsequently, the review synthesizes clinical evidence for the role of R/S in managing affective disorders while exploring how spiritually oriented interventions can leverage these neurobiological mechanisms. Ultimately, this review will argue for a new paradigm of integrative pluralism in mental healthcare, one that recognizes the profound neurobiological reality of the human search for meaning and connection, and advocates for a holistic approach that combines conventional treatments with targeted R/S practices.

Distributed Neural Networks Involved in Processing Religious and Spiritual Experiences

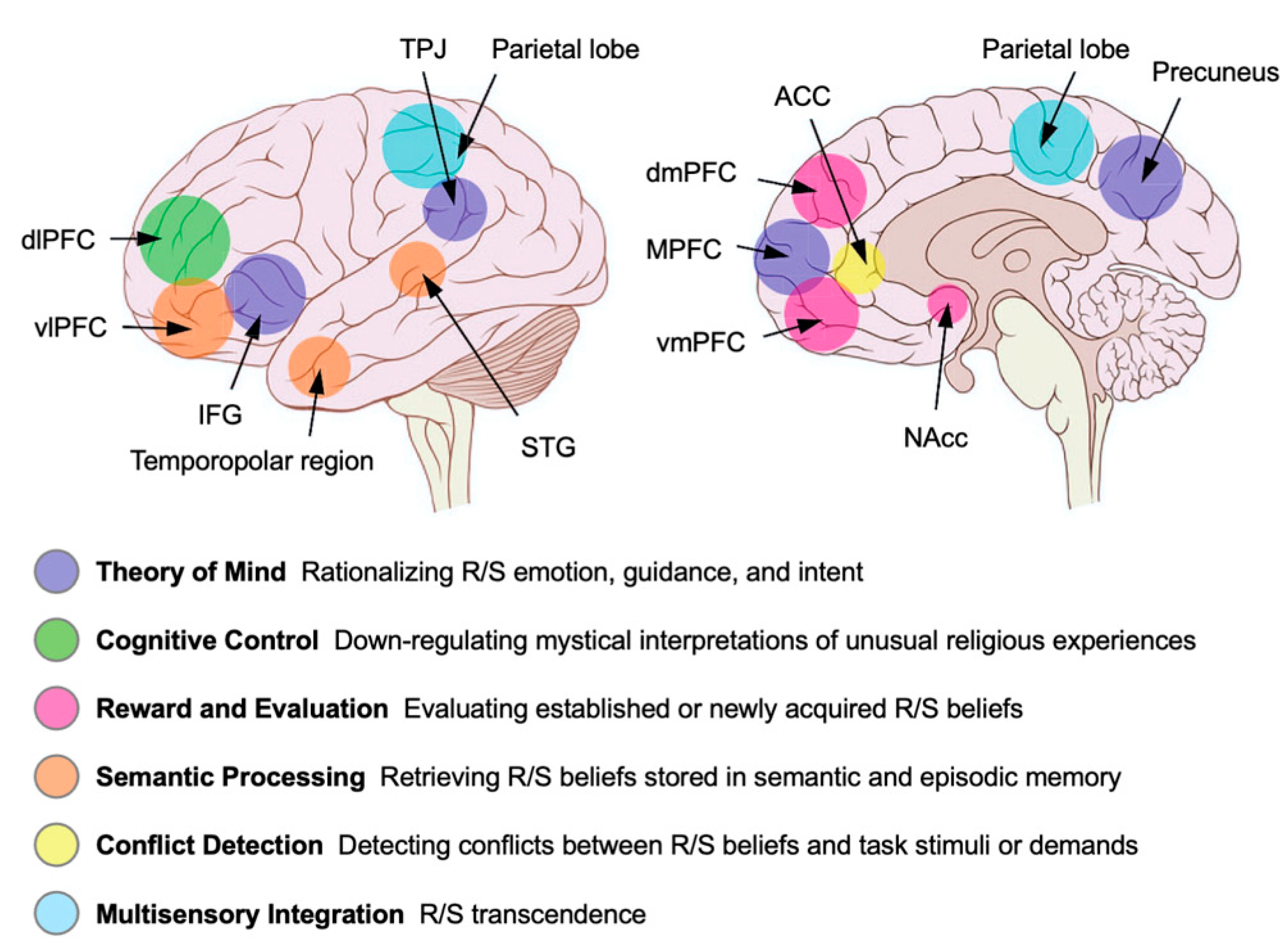

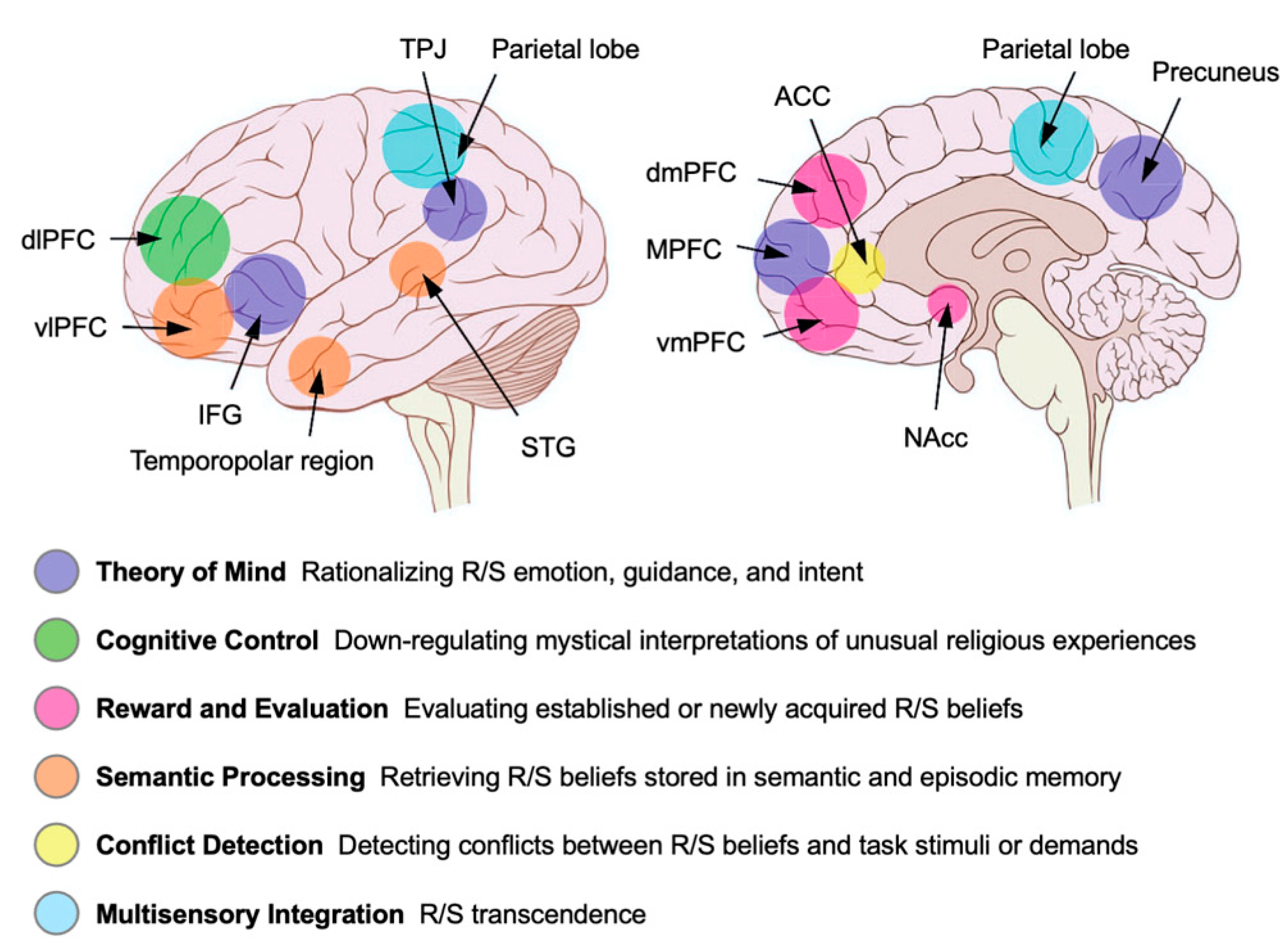

To understand the profound impact of religion and spirituality on mental health, it is strategically essential to first map their foundations within the brain's structural and functional architecture (

Figure 1). Early popular speculation about a single "God spot" has been decisively refuted by a wealth of neuroscientific research. Instead, the evidence points to a complex and distributed set of large-scale neural networks that are recruited during religious and spiritual experiences [

6,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Critically, these networks are not unique to R/S but are the same systems integral to other core human cognitive functions, including social cognition, self-awareness, morality, and emotional regulation. The section below synthesizes findings from lesion studies, neuroimaging, and pathology research to build a distributed network model of the religious brain.

Neuroanatomical Substrates of Religious and Spiritual Experience

Evidence from patients with brain lesions, direct cortical stimulation, and neuropathology provides crucial causal insights into the roles of specific brain structures in facilitating or inhibiting spiritual experiences. Far from being localized to a single area, these experiences emerge from the interplay of regions throughout the cerebral cortex and limbic system.

The limbic system, including the amygdala, hippocampus, and temporal lobes, forms the emotional and visionary core of R/S experiences (

Figure 1). The amygdala is central to processing emotions such as awe, fear, and joy, which are frequently reported during intense spiritual experiences, while the hippocampus is crucial for encoding and recalling vivid spiritual memories. Functional neuroimaging studies have shown that religious experiences often activate these limbic structures, correlating with feelings of transcendence and emotional intensity [

20]. For example, fMRI research by Beauregard and Paquette (2006) demonstrated increased limbic activation during prayer in Carmelite nuns, linking these regions to the subjective sense of union with God [

21]. Pathological conditions such as temporal lobe epilepsy can produce ecstatic seizures and a state of hyper-religiosity, with patients reporting visions, auditory hallucinations, and overwhelming spiritual feelings [

22,

23]. Lesion mapping and case studies further support the temporal lobe’s unique capacity to generate profound spiritual phenomena, as seen in individuals who develop intense religious interests following temporal lobe injury.

The frontal lobes, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and orbitofrontal cortex, play a central role in executive functions essential for religious life, such as moral reasoning, emotional regulation, and impulse control (

Figure 1). The dlPFC acts as a top-down regulator, helping individuals reflect on ethical dilemmas or control emotional impulses during prayer or meditation. In a landmark lesion study, Cristofori et al. (2016) found that veterans with penetrating brain injuries to the dlPFC reported a greater frequency of mystical experiences compared to healthy controls, suggesting that the dlPFC normally inhibits mystical states and that its attenuation can disinhibit neural systems responsible for such experiences [

24]. Additional neuroimaging research by Azari et al. (2001) revealed that the prefrontal cortex is activated during religious contemplation, supporting its role in belief formation and moral judgment [

25]. Recent lesion studies have also shown deep-brain regions, such as the periaqueductal gray region of the brainstem which plays a role in regulating fear, pain, and altruistic behaviors, are also associated with religious and spiritual beliefs [

26].

Observations from the study of epilepsy and seizures has revealed additional neurophysiological support for the involvement of the frontal and temporal lobes in powerful R/S experiences. The phenomenology of these observations, particularly during ecstatic seizures, is characterized by a complex array of auras including intense well-being, heightened self-awareness, and a mystical sense of unity with the world, often accompanied by somatic sensations like ascending warmth and perceptual shifts such as time dilation [

23,

27]. The explicitly religious character of these states has led to historical associations with figures like Saint Theresa of Avila [

28]. Research efforts to localize these profound subjective states has progressively refined our understanding of their neural origins. Prevailing scientific paradigms have historically posited a strong association between ictal religious experiences and Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (TLE), with particular emphasis on the predominance of right-sided TLE as a neuroanatomical substrate. Nevertheless, recent advances in neuroimaging, lesion mapping, and network neuroscience have challenged this reductionist perspective, elucidating a more intricate and dynamic model wherein religious and spiritual phenomena are understood to arise from the coordinated activity of distributed neural networks rather than from isolated temporal lobe pathology. This research implicates a network where epileptic discharges originating in a temporal lobe epileptogenic zone propagate to and trigger hyperactivation of the anterior insula, believed to be the direct symptomatogenic zone responsible for generating an ecstatic religious state [

23,

27,

28]. This neurological framework is further elucidated by the timing of these experiences, which can manifest during seizures (ictal), after seizures (postictal), or between them (interictal), with postictal events sometimes leading to profound religious conversions and interictal states manifesting as a more pervasive hyper-religiosity). The underlying electrical activity often involves transient, focal, epileptic-like spikes or sharp wave discharges in the temporal lobe, which is a neural signature observed in glossolalia (speaking in tongues) and peak states of transcendental meditation, reinforcing the link between specific patterns of neural activity and the genesis of intense spiritual experiences [

29,

30].

The parietal lobes, particularly the posterior superior parietal lobule (PSPL), are crucial for representing the spatial boundaries between the self and the external world. During deep meditation, focused attention in the prefrontal cortex can lead to functional cutting off in sensory drive to the PSPL through a process known as deafferentation [

31]. This disruption can cause the brain to lose its usual ability to distinguish between self and others, resulting in profound experiences of unity, boundlessness, or self-transcendence. Neuroimaging studies by Newberg et al. (2010) using SPECT scans have shown decreased activity in the frontal and parietal lobes during meditation, correlating with reports of self-transcendence and unity [

32]. Lesion studies further support this role. Damage to posterior brain areas, including the inferior parietal lobe (IPL), can induce a selective increase in self-transcendence, making individuals more likely to report feelings of merging with something greater than themselves [

33]. For instance, people with these lesions may describe experiences of losing their sense of individual identity during prayer or meditation, feeling instead a deep unitary connection with all existence. These findings from lesion mapping, neuroimaging, and clinical case studies provide robust scientific support for the involvement of the limbic system, frontal lobes, and parietal lobes in the generation and modulation normal R/S experiences from the routine to supernatural.

Brain Networks and Neural Dynamics in Spirituality

As described above, complex cognitive states such as religious belief and spiritual experience do not arise from isolated brain regions but instead emerge from the coordinated activity of large-scale neural networks. The Triple Network Model has become a powerful framework for understanding how the brain dynamically shifts between internal reflection, external focus, and the detection of salient spiritual stimuli [

7]. This model highlights the interplay among three key networks that are the Default Mode Network (DMN), the Frontoparietal Network (FPN), and the Salience Network (SN) in R/S experience and practice (

Table 1).

It is widely recognized the DMN is most active during periods of rest and is primarily involved in self-referential thought, such as reflecting on one’s past, envisioning the future, or considering one’s identity. Neuroimaging studies have shown that practices like meditation and experiences induced by classic psychedelics like psilocybin are associated with a significant reduction in DMN activity. It demonstrated that both meditation and psychedelic states lead to decreased DMN connectivity, which correlates with the subjective experience of ego dissolution described as a temporary fading of the sense of self or no longer feeling as an individual separated from nature and others [

34]. Participants report this phenomenon as a sense of unity with the universe or a loss of self-boundaries, which is a hallmark of many mystical and spiritual experiences [

23,

24,

31,

34]. A fascinating neuroimaging study demonstrated that this altered sense of self during glossolalia is associated with significantly decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex, left caudate, and left temporal pole. These decreases were accompanied by significant increases in activity of the right amygdala and left superior parietal lobe [

35]. This brain activity signature is consistent with neurocognitive descriptions of glossolalia from Charismatic faith that explain it as a divine language occurring through a meeting between the Holy Spirit and human, which occurs particularly during prayer and worship, evoking beauty, awe, power, intimacy, and a deepening of faith [

36].

The Frontoparietal Network (FPN), also known as the Central Executive Network (CEN), functions as the brain’s executive control center. The FPN is engaged during cognitively demanding tasks that require focused, goal-directed thought, such as problem-solving, working memory, and planning. In the context of religious practice, the FPN is recruited for complex doctrine analysis, moral reasoning, and the interpretation of religious texts (

Table 1). For instance, fMRI studies have shown that the FPN is activated when individuals engage in theological reflection or attempt to resolve moral dilemmas within a religious framework [

37]. This network’s involvement underscores the cognitive complexity and executive demands of religious cognition.

The Salience Network (SN) acts as a dynamic switch, continuously monitoring both the internal and external environments for personally relevant or meaningful information. When a spiritually significant stimulus is detected whether it is an internal feeling, such as a sense of awe during prayer, or an external symbol, such as a religious icon, the SN disengages the internally focused DMN and activates the externally focused FPN, thereby directing cognitive resources toward the salient stimulus. This switching mechanism is crucial for the rapid allocation of attention and emotional resources during R/S experiences (

Table 1). Studies using EEG and fMRI have shown that the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex, key nodes of the SN, are activated during moments of religious euphoria or when individuals report sensing the presence of the divine [

38]. As previously discussed, electrical activity in the anterior insula drives elicit mystical and euphoric religious experiences accompanied by increased self-awareness and enhanced mental clarity [

23].

A distinct but related network critical to religious cognition is the Theory of Mind (ToM) network. This system, which includes regions such as the precuneus and medial prefrontal cortex, is essential for social cognition, allowing individuals to infer the intentions, beliefs, and emotional states of others (

Table 2). Seminal fMRI research by Kapogiannis and colleagues (2009) demonstrated that this network is robustly engaged when individuals contemplate the intentions and emotions of supernatural agents, such as God or spiritual beings [

39]. This finding suggests that our relationship with God or other supernatural entities is processed using the same neural architecture that evolved for navigating complex human social relationships, highlighting the deeply social nature of religious thought. Collectively, these findings reveal that the structural and functional anatomy of R/S experience is not localized but is instead a complex, distributed system deeply integrated with core cognitive processes. This network-based perspective lays the groundwork for exploring the underlying biochemical and physiological processes that further modulate these experiences, offering a comprehensive understanding of the neurobiology of spirituality (

Table 2).

Neurochemical and Biomarker Correlates of Spirituality

Having established the neuroanatomical architecture involved in R/S beliefs and practices, the section below examines neurochemical and biological markers that mediate them. These molecules and neurobiological effectors represent signaling pathways through which beliefs and practices translate into subjective experience, as well as objective health and quality of life outcomes. Understanding these signaling pathways is essential for further elucidating how R/S practices can shape our biology, offering a mechanistic explanation for their profound effects on mood, social connection, and resilience.

Dopamine and the Reward System in Religious and Spiritual Practices

Central to motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement, the brain’s reward system is a complex circuit involving the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc). The VTA located in the midbrain is a major source of dopaminergic neurons that project to various brain regions, including the nucleus accumbens, which is often referred to as the brain’s pleasure center. Dopamine (DA), a key neurochemical in this system, is released in the NAc as final reinforcement cue in the classic brain reward cascade. The DA reward system provides a neurobiological mechanism for the comfort and psychological reinforcement many people derive from religious belief and practice. Studies have shown that activities such as prayer, worship, and meditation can activate the reward system, leading to increased dopamine release and positive affect. For example, functional MRI research by Schjoedt et al. (2009) demonstrated that personal prayer activates the NAc, suggesting that prayer can be experienced as a rewarding interaction, like other pleasurable activities [

40]. Likewise, PET imaging studies have demonstrated DA release during intense yoga meditation, further supporting the link between spiritual practices and the brain’s reward pathways [

41]. The positive feelings associated with religious rituals, a sense of divine connection, or spiritual transcendence are mediated, in part, by DA release in this system (

Table 3). These reward mechanisms help explain why religious and spiritual experiences can be deeply comforting and reinforcing, motivating individuals to seek out these practices repeatedly.

Genetic research further supports the connection between dopamine and spirituality. Specific variations in the dopaminergic D4 receptor gene (DRD4) and the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 gene (VMAT2) have been associated with the personality trait of spirituality and self-transcendence [

42]. Individuals with certain DRD4 polymorphisms may be more predisposed to novelty seeking and spiritual experiences, while VMAT2 is involved in regulating dopamine storage and release. These genetic findings suggest that some people may be biologically predisposed to experience greater spiritual sensitivity or reward from religious practices. These studies collectively illustrate the fundamental role of the brain’s reward system in shaping the emotional and motivational aspects of religious and spiritual life, providing a biological basis for the comfort, meaning, and psychological reinforcement that many individuals derive from their faith.

Endogenous Opioids and Oxytocin in Religious Bonding and Spiritual Affiliation

Religious rituals are potent drivers of social cohesion and group bonding, and this effect appears to be mediated by the brain's endogenous opioid system (

Table 3). Research demonstrates that collective rituals foster social bonding through the release of μ-opioids, the same class of neurochemicals targeted by drugs like morphine. In a series of compelling studies, pain threshold which is a reliable proxy for endogenous opioid activation was shown to increase after participation in prayer [

43]. Critically, when prayer participants are administered Naltrexone, the pro-social bonding effects of the ritual were eliminated [

44]. These finding strongly indicates that μ-opioid activation is a necessary mechanism for the social benefits derived from ritual participation. Religious rituals are potent drivers of social cohesion and group bonding, and this effect appears to be mediated by the brain’s endogenous opioid system [

45]. The endogenous opioid system including neurochemicals like β-endorphin and enkephalins plays well established roles in pain relief, pleasure, and the regulation of social attachment. During collective rituals, such as group singing, synchronized dancing, chanting, or communal prayer, there is a measurable release of μ-opioids (

Table 3). This neurochemical release is thought to underlie the feelings of warmth, trust, and unity that participants often report during and after such rituals [

45,

46].

Exploration into the biological foundations of religious experience also highlights the significance of the oxytocin system. Recognized as a neurohormonal substrate for human social affiliation, oxytocin provides a logical and well-supported framework for examining the neurobiology underlying spiritual bonding and connection [

47]. This framework was initially supported by correlational studies identifying a positive association between endogenous oxytocin levels, assayed in both plasma and saliva, and self-reported spirituality [

48,

49]. Mechanistic studies support a causal association by demonstrating that intranasal oxytocin administration increased self-reported spirituality and enhanced positive emotions during meditation [

50]. Other support comes from neurobiological overlap between the neural circuits of the “social brain” and the “religious brain” highlighted by fMRI data showing brain activity during profound religious experiences correlates with peripheral oxytocin levels [

51]. Other research has shown that oxytocin’s effects on spirituality depend on individual differences, enhancing experiences for those low in absorption while dampening them for those high in absorption [

52]. Further complicating the picture, Tønnesen et al. (2019) found no link between oxytocin and religious commitment but identified a positive correlation with Neuropeptide Y (NPY), a hormone tied to stress resilience and anxiety regulation [

53]. Taken together, this complex and at times contradictory body of evidence strongly suggests that the neurobiology of spirituality cannot be attributed to a single spiritual hormone but rather emerges from the interplay of multiple neurohormonal systems [

46]. Future research must therefore investigate the dynamic interplay between neurohormonal systems, particularly oxytocin and NPY. Such work must account for moderating variables, such as genetic predispositions, personality traits like absorption, and socio-cultural context, in order to clarify mechanisms shaping religiosity, spirituality, and social cohesion [

50,

52].

Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) and Endocrine Markers of Faith

The field of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) investigates the intricate connections between the brain, behavior, and the immune system, offering a multidisciplinary perspective on how psychological and social factors can influence physical health. PNI research has identified a range of biomarkers, such as cortisol, salivary alpha-amylase (SAA), and inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6 (IL-6), that are sensitive to psychological stress and social conditions. These biomarkers provide quantitative indicators of how mental states and social interactions can impact immune function and overall health. Importantly, studies have shown that aspects of religion and spirituality (R/S) are closely linked to these biological markers (

Table 3). For example, higher levels of spiritual engagement have been associated with lower levels of stress hormones such as cortisol, suggesting that spiritual practices may buffer the physiological effects of stress. In breast cancer survivors, research found that spiritual self-rank and forgiveness were correlated with reduced levels of salivary alpha-amylase, a marker of sympathetic nervous system activity, indicating a potential pathway through which spirituality can promote resilience and recovery [

54]. Similarly, positive congregational support and spiritual coping have been linked to lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and C-Reactive protein (CRP), which are associated with chronic stress and disease progression [

55].

These findings provide a biological link between faith and physical health, demonstrating that religious and spiritual practices can influence immune system function and disease outcomes. By integrating insights from neuroscience, immunology, and behavioral science, PNI offers a interdisciplinary scaffold for understanding how spiritual life can contribute to holistic health and resilience. Furthermore, the clear associations between R/S variables and these neurochemical and immune markers bridge the gap between subjective experience and objective physiology, setting the stage for quantitative investigations into their effects on mental health outcomes, particularly depression and anxiety.

Religion and Spirituality in the Management of Affective Disorders

The neurobiological evidence presented thus far demonstrates that religion and spirituality are not abstract epiphenomena but are deeply rooted in the brain's core systems of emotion, social cognition, and reward. The section below will build upon this foundation to review the clinical and psychophysiological evidence supporting the role of R/S as a potent enhancer of mental health, resilience, and recovery. By examining epidemiological data, therapeutic interventions, and stable trait markers, we can appreciate how R/S can be integrated into the effective management of depression and anxiety.

Epidemiological and Clinical Evidence

A substantial body of prospective research indicates that religion and spirituality (R/S) can serve as protective factors against both the onset and recurrence of depression. For example, a systematic review by Braam and Koenig (2019) analyzed 152 prospective studies and found that in nearly half of these studies (49%), at least one measure of R/S predicted a better course of depression over time [

12]. This suggests that engagement in religious or spiritual practices may help buffer individuals against depressive symptoms and promote resilience. However, this protective effect is not universal and depends critically on the nature of an individual's religious engagement. Braam and Koenig (2009) also described that measures of religious struggle, such as feeling punished by God, experiencing spiritual doubts, or perceiving conflict within one's faith community, were significantly associated with higher rates of depression in 59% of the studies that included this variable [

12]. This highlights the importance of a positive, supportive spiritual framework, as a conflict-ridden or punitive religious experience can be detrimental to mental health (

Figure 2).

The protective influence of R/S has been leveraged in clinical practice through the development of spiritually integrated psychotherapies. These interventions adapt established modalities like CBT to align with a patient's religious worldview. For instance, spiritually integrated CBT incorporates concepts such as hope, forgiveness, belonging, purpose, and altruism which are values that are often central to religious traditions (

Figure 2). Clinical trials have demonstrated that these therapies can lead to improved outcomes for religious patients struggling with depression. For example, Koenig et al. (2015) conducted a pilot randomized trial comparing religiously adapted CBT to conventional CBT in individuals with chronic medical illness and major depression, finding that the religiously adapted approach was particularly effective for those with strong religious beliefs [

56]. Similarly, Rickhi et al. (2011) found that a spirituality teaching program for depression led to significant improvements in depressive symptoms [

57]. Such adaptations recognize that for many individuals, spiritual beliefs provide the fundamental framework for making sense of suffering and finding a path toward healing. By integrating spiritual values and religious practices into evidence-based psychotherapy, clinicians can offer more personalized and effective care, especially for patients whose worldview is shaped by faith.

Neurophysiological Markers of Resilience

Longitudinal research provides compelling evidence for a stable neurophysiological marker that may underlie the resilience-promoting effects of religion and spirituality (R/S). In a multi-decade study of families at both high and low risk for depression, Tenke and colleagues (2013, 2017) examined resting posterior EEG alpha oscillations. They found that individuals who rated R/S as highly important demonstrated significantly greater posterior alpha power [

10,

58]. This is a critical finding, as prominent resting alpha is considered a potential biomarker for resilience against depression. The significance of this result is underscored by the fact that posterior alpha power is associated with affective stability and emotional regulation. Higher alpha activity in the posterior regions of the brain has been linked to reduced vulnerability to stress and improved mood regulation, both of which are protective factors against depressive disorders. Remarkably, the association between R/S importance and posterior alpha power held true even when the EEG was measured twenty years after the initial R/S rating was given, suggesting that this neurophysiological trait is both stable and enduring over time [

10]. This long-term stability implies that prominent posterior alpha may serve as a trait marker linked to a disposition toward spirituality, which in turn confers protection against depression.

The findings from Tenke and colleagues (2013 and 2017) are supported by other studies showing that individuals who engage in regular spiritual or religious practices often exhibit neurophysiological patterns associated with greater resilience and mental health. For example, research has demonstrated that meditation and contemplative prayer can enhance alpha and theta oscillations, further supporting the role of spiritual engagement in promoting neural mechanisms of emotional well-being [

59]. Spiritual resilience is supported by a network of neurobiological mechanisms that include the modulation of brain networks, activation of reward and bonding neurochemistry, regulation of stress and immune responses, and the development of stable neurophysiological traits. These mechanisms work together to foster emotional stability, social connection, and adaptive coping, making spirituality a potent resource for mental health and well-being. These studies suggest that the relationship between spirituality and mental health is not merely psychological or social, but is also reflected in stable, measurable patterns of brain activity that may help protect individuals from the onset and recurrence of depression.

Contrasting Neurocircuitry of R/S Practices and Affective Disorders

Clinical and neurophysiological research has demonstrated that R/S practices can actively counteract the neural circuit dysfunctions commonly seen in depression and anxiety. Neuroimaging studies reveal that the same large-scale brain networks affected in mood disorders are modulated in a therapeutic direction by spiritual engagement. For instance, in depression and anxiety, the DMN often shows hyper-connectivity, resulting in excessive self-referential thought, persistent rumination, and negative self-focus. However, interventions such as mindfulness meditation, contemplative prayer, and even psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) have been shown to decrease DMN activity, leading to reduced rumination and a sense of ego-dissolution or self-transcendence. This effect has been observed in studies by Barrett and Griffiths (2018), where participants reported a profound sense of unity and relief from negative thought cycles following meditation or psilocybin administration [

34].

Executive control, mediated by the PFC, is often impaired in affective disorders, resulting in poor emotional regulation and difficulty with cognitive reappraisal. Clinical neuroscience research, including fMRI studies have shown that religious contemplation, doctrinal analysis, and personal prayer robustly activate the PFC, enhancing executive control and regulatory function [

6,

7,

38]. This increased engagement supports better emotional stability and cognitive flexibility, which are crucial for recovery from depression and anxiety. Additionally, spiritually integrated psychotherapies, such as religiously adapted CBT, have demonstrated improved outcomes for patients with depression, further supporting the role of spiritual practices in strengthening executive function [

56].

Reward processing is another domain where R/S practices exert a therapeutic effect. Depression is frequently marked by anhedonia and amotivation, reflecting dysfunctional reward circuitry. Neuroimaging and PET studies have shown that spiritual activities such as prayer, worship, and meditation can activate dopaminergic pathways, particularly in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens [

7,

60]. Religious practices and spiritual beliefs engage the brain’s reward system, mediating positive affect, motivation, and psychological reinforcement [

42]. This activation helps counteract the blunted reward response seen in depressive states, and similar effects have been observed in studies of yoga meditation and group rituals. In fact, social connection, which is often disrupted in mood disorders, is also improved by R/S engagement. Feelings of isolation and impaired relational security are common in depression and anxiety, but spiritual practices, especially those involving a sense of connection to a higher power or participation in communal rituals, activate the ToM network. Seminal fMRI research by Kapogiannis et al. (2009) demonstrated that this network, which includes the precuneus and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), is robustly engaged when individuals contemplate the intentions and emotions of supernatural agents [

39]. This engagement fosters a sense of connection and relational security, helping to mitigate feelings of isolation. As discussed above, studies have shown that participation in group religious rituals can modulate endogenous release of opioids, oxytocin, and NPY to further enhancing social bonding and emotional well-being.

The literature clearly shows religious convictions, and spiritual practices are not merely supportive or palliative but may function as active neurobiological interventions that restore healthy brain network dynamics. This understanding has inspired the development of novel, spiritually oriented therapies, such as psychedelic-assisted treatments (PAT) and spiritually integrated psychotherapy, which directly leverage these neurobiological mechanisms to produce durable clinical benefits for individuals suffering from depression and anxiety as further discussed below.

The Emerging Role of Entheogens and Psychedelics in Mental Health

The exploration of the neurobiology of spirituality finds a powerful and pragmatic application in the contemporary renaissance of

entheogen (psychedelic) research. Classic entheogens such as psilocybin are not merely recreational substances. They are potent pharmacological tools found in nature that can reliably produce ecstatic spiritual and mystical-type experiences under appropriate conditions [

61,

62,

63]. When administered in a supportive clinical context, these substances have been shown to produce profound neuroplasticity and lasting therapeutic benefits for individuals suffering from severe depression and anxiety, representing a paradigm shift in psychiatric treatment. Beyond their clinical efficacy, entheogens are uniquely capable of catalyzing deeply spiritual experiences [

61,

62,

63,

64]. Participants in entheogen-assisted therapy frequently report transformative states marked by a sense of unity, transcendence, and connection to something greater than themselves. These mystical experiences often include feelings of awe, dissolution of the ego, and a profound sense of meaning or sacredness. Such states are not only subjectively powerful but have been strongly correlated with improvements in psychological well-being, reductions in anxiety, and enduring increases in life satisfaction and prosocial attitudes.

Clinical trials have demonstrated that psilocybin-assisted therapy can lead to rapid and sustained reductions in depressive symptoms, even among patients with treatment-resistant depression or those facing life-threatening illnesses. Importantly, the depth of the spiritual or mystical experience induced by the entheogen is often the strongest predictor of long-term therapeutic benefit [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. Participants who undergo these transformative experiences frequently describe a renewed sense of purpose, greater emotional openness, and enhanced capacity for forgiveness, gratitude, and connection with others [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. By facilitating access to profound spiritual states, entheogens offer a unique therapeutic avenue that addresses not only the symptoms of mental illness but also the existential and spiritual dimensions of human suffering. This integrative approach combining conventional psychiatric and spiritual care with the targeted use of entheogens holds promise for restoring hope, meaning, and adaptive neural network function in those struggling with depression and anxiety.

The therapeutic effects of entheogen-based therapy or PAT extend far beyond mere symptom relief. These approaches frequently encompass enduring transformations in personal outlook, heightened emotional openness, and a deepened capacity for forgiveness and gratitude. Individuals undergoing entheogen experiences often report profound shifts in their sense of self and connection to others, which can foster lasting psychological resilience and well-being. Neuroimaging and EEG studies have begun to clarify the mechanisms underlying these benefits, revealing that entheogens like psilocybin and N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) induce significant changes in brain network connectivity with most notable changes occurring within the PFC often to include a disorganization and downregulation of DMN influence [

70,

71,

72]. As similarly discussed above, reduction in DMN activity during the entheogenic experience is closely linked to reports of ego dissolution and a powerful sense of unity, further connecting the neurobiological effects of these substances to their transformative therapeutic impact. This convergence of clinical and neuroscientific evidence highlights the potential of entheogen-assisted therapy as a groundbreaking intervention for mental health conditions, with the depth and quality of the mystical experience serving as a key mediator of its long-term benefits.

Therapeutic Efficacy and Lasting Change Produced by Psychedelic Therapy

A growing body of rigorous, placebo-controlled clinical trials has demonstrated the remarkable therapeutic efficacy of entheogen-assisted therapy, particularly with agents such as psilocybin and DMT, in the treatment of depression and anxiety [

69,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. For example, studies have shown that a single high dose of psilocybin, administered in a supportive psychological setting, can produce rapid, substantial, and sustained reductions in symptoms even among patients facing life-threatening cancer diagnoses [

78,

79]. In a landmark trial by Ross et al. (2016), patients with advanced cancer experienced significant decreases in both depression and anxiety following psychedelic-assisted therapy, with effects persisting for months after treatment [

78]. Similarly, Shnayder et al. (2023) reported improvements in psycho-social-spiritual well-being in cancer patients, further supporting the durability of these benefits [

79]. Interestingly, these effects are not limited to clinical populations. Studies with healthy volunteers have also demonstrated that a single entheogen session can lead to significant improvements in mood, well-being, and life satisfaction that last for months. For instance, research by Griffiths et al. (2017) found that participants reported enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors after a single psychedelic-assisted treatment session [

67].

Importantly, the therapeutic outcome of entheogen-assisted therapy is not simply a result of its pharmacological action but is directly mediated by the nature of the subjective experience it produces. The intensity of the mystical experience as measured by validated scales such as the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ30) has emerged as the single best predictor of positive long-term therapeutic and spiritual outcomes. Participants who undergo a more complete mystical experience report greater and more enduring increases in life meaning, altruism, gratitude, and forgiveness, which are central to their recovery and overall well-being. These findings have been replicated across multiple studies, highlighting the importance of the subjective, transformative aspects of the entheogenic experience in driving lasting clinical benefits [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. Studies of DMT have also revealed this compound can produce intense visionary and relational experiences, often described as encounters with indescribable forms, supernatural information, and unworldly entities, which parallel the dialogic nature of prophetic and spiritual states [

80,

81,

82]. These clinical and neuroscientific findings underscore the potential of entheogen-assisted therapy including both psilocybin and DMT treatment as powerful interventions for depression and anxiety, with the quality of the spiritual, supernatural, and mystical experiences serving as key indicators of its long-term benefits.

Neurobiological Parallels of Psychedelic Experience to Spiritual Practice

The neurobiological effects of psychedelics show striking parallels to those observed during traditional contemplative practices and deep prayer, providing a convergent line of evidence for the mechanisms underlying self-transcendence. A key shared neural signature is the marked reduction in the activity and connectivity of the DMN as described. Neuroimaging studies, such as those by Barrett and Griffiths (2018), have demonstrated that both meditation and psychedelic states lead to decreased DMN connectivity [

34]. These experiences are central to both the psychedelic state and the goals of many meditative traditions, such as those found in Buddhist or contemplative Christian practices, where practitioners report a sense of unity with the universe or a merging with a higher reality. This convergence suggests a common neural pathway through which both pharmacological interventions like psychedelics and behavioral interventions such as meditation or prayer can induce profound states of self-transcendence.

Curiously, the phenomenology of some psychedelic experiences aligns with historical and cross-cultural descriptions of prophecy and visionary states. Rick Strassman has proposed a theoneurological model based on research with DMT. As described above, Strassman notes that the DMT state often involves interactive-relational encounters that parallel the dialogic nature of biblical prophecy, where prophets report receiving messages or guidance from divine beings [

81]. This stands in contrast to the unitive mystical experiences often associated with psilocybin or meditation, which involve a merging with an undifferentiated whole or a sense of oneness with all existence. Deep meditation, contemplative practices, and prayer have the remarkable capacity to evoke transcendent states that closely mirror those induced by entheogens. These practices can facilitate profound experiences of unity, ego dissolution, and expanded consciousness, highlighting the shared neurobiological mechanisms that underlie both spiritual and psychedelic pathways to self-transcendence. The diverse ways in which altered states of consciousness can manifest map onto different traditions of R/S practice and experience suggesting that the brain can generate a wide spectrum of spiritual and mystical phenomena depending on the context, intent, and method of induction. A provocative hypothesis is that deep religious contemplation, prayer, and spiritual meditation may trigger the endogenous release of DMT to mediate the human sense of awe, experience of visions, and loss of sense of self while reinforcing beliefs and convictions [

83,

84,

85]. For certain, modulation of 5-HT, DA, and neurohormonal signaling pathways are modulated during R/S practices to produce healthy outcomes. In summary, the convergence of findings from clinical psychology, contemplative neuroscience, and psychedelic research provides a powerful synthesis, compelling us to consider a new, more integrated paradigm for the future of mental healthcare.

Clinical Implications and Translational Recommendations

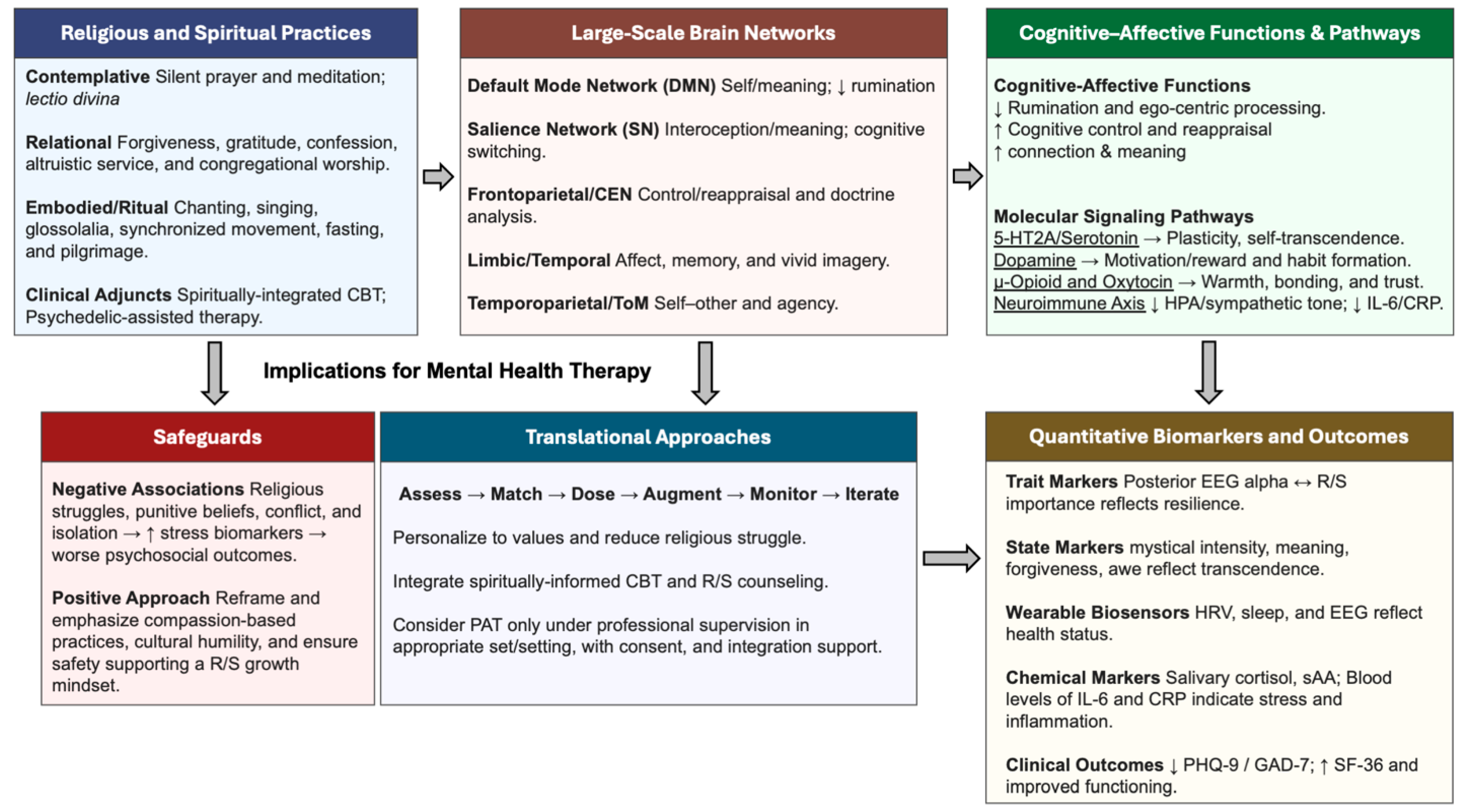

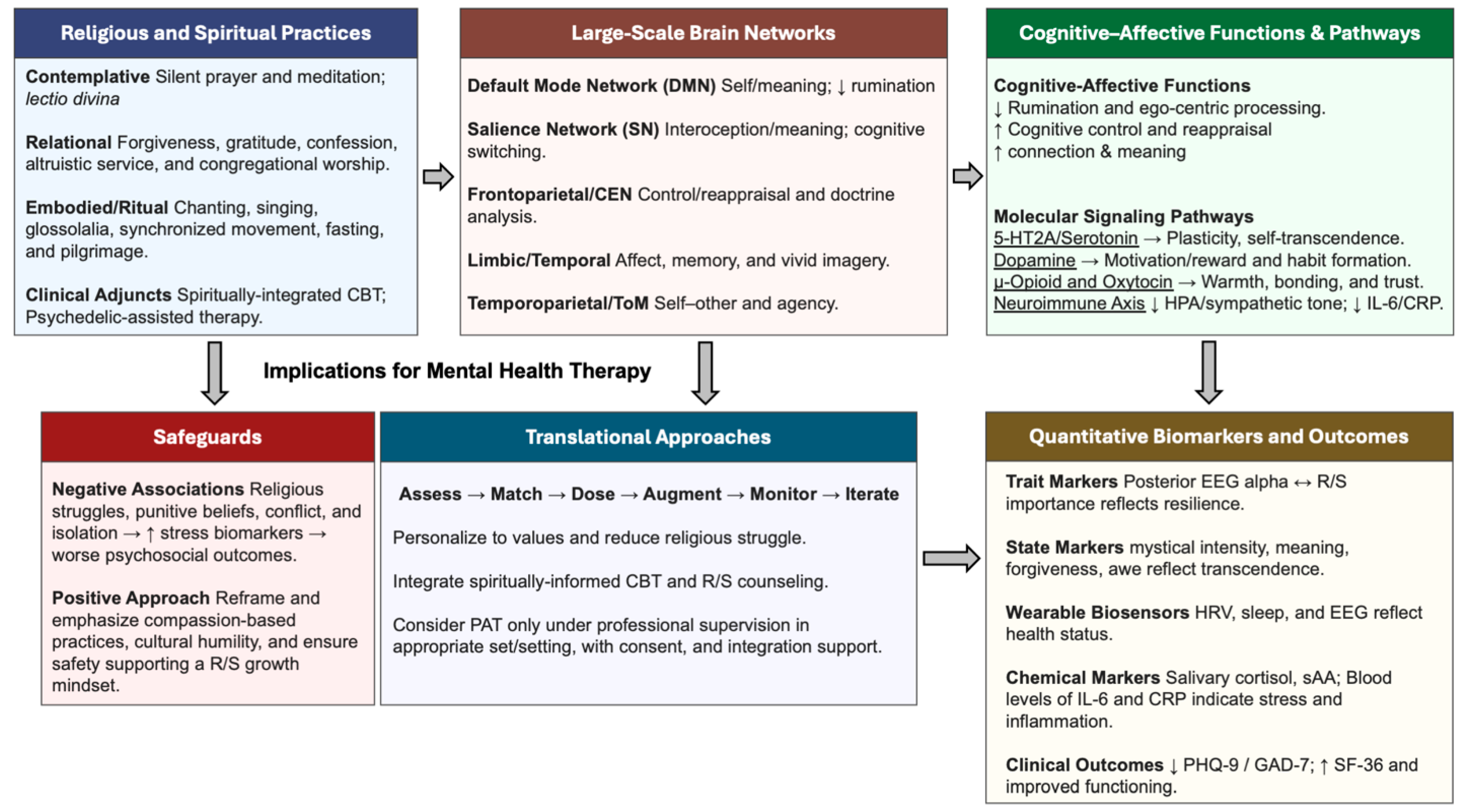

An Integrated Spiritual Neurotherapeutics Model for affective disorders emphasizes the translation of robust neurobiological and clinical evidence into actionable strategies for mental health care (

Figure 2). Clinicians are encouraged to incorporate respectful and nonjudgmental spiritual assessments as a standard part of comprehensive care, recognizing the high prevalence and impact of religious and spiritual (R/S) beliefs among patients. Such assessments, endorsed by professional organizations and included in psychiatric training curricula, enable practitioners to understand how patients use R/S to cope, identify spiritual distress, and facilitate meaningful discussions about these dimensions. This approach ensures that care is both ethical and evidence-based, honoring the full complexity of each patient’s experience (

Figure 2).

Therapeutically, clinicians should leverage positive R/S variables by supporting practices and beliefs linked to better outcomes, such as forgiveness, life purpose, and social connection through community engagement. Existing modalities like CBT can be adapted to integrate R/S practices like gratitude, altruism, accountability, and devotion making therapy more relevant and effective for religious patients. It is also crucial to distinguish positive religious coping, which is protective, from negative coping or religious struggle, which can worsen depression and requires direct clinical attention. By differentiating these forms of coping, clinicians can tailor interventions to maximize resilience and recovery (

Figure 2). These recommendations form part of a holistic model that moves beyond reductionist approaches, advocating for integrative pluralism. This framework draws on insights from neuroscience, psychology, sociology, anthropology, and theology, recognizing that while the brain shapes experience, it does not solely define it. By embracing an integrated neurospiritual model, mental health care can harness patients’ beliefs as powerful resources for healing and growth [

86,

87,

88,

89,

90]. Framing this model as the future standard of care aligns clinical practice with patients’ deepest values and offers a more complete path to human flourishing.

Conclusions

This review has synthesized a broad range of evidence demonstrating that religious and spiritual life is not a mere psychological or social epiphenomenon but is deeply rooted in the core neurobiology of the human brain. Modern neuroscience has shown that spiritual experiences arise from the coordinated activity of large-scale neural networks, such as the Default Mode Network, Frontoparietal Network, and Salience Network, which play fundamental roles in self-awareness, executive function, and emotional regulation. Functional neuroimaging, lesion mapping, and electrophysiological studies have revealed that these networks are dynamically modulated during religious practices, meditation, and mystical states, supporting the idea that spirituality is an integral part of our neurocognitive architecture. Moreover, neurochemicals in the brain’s reward and social bonding systems including dopamine, endogenous opioids, and oxytocin play crucial roles in mediating the comfort, motivation, and sense of connection that many individuals derive from religious and spiritual engagement. Clinical and experimental studies have demonstrated that spiritual practices can activate these neurochemical pathways, leading to measurable improvements in mood, resilience, and social cohesion. For example, participation in group rituals has been shown to increase endogenous opioid release, fostering social bonding, while prayer and meditation can stimulate dopaminergic activity, reinforcing positive affect and psychological well-being.

The profound therapeutic effects, such as reductions in depression and anxiety, enhanced emotional control, and increased resilience produced by religious and spiritual practices are a direct reflection of the underlying neurobiology. Placebo-controlled trials of spiritually integrated therapies and psychedelic-assisted treatments have further highlighted the capacity of spiritual experiences to produce lasting improvements in mental health, often mediated by neuroplastic changes in brain network connectivity and molecular signaling. These findings challenge us to move beyond reductionist models of mental illness and treatment, which focus solely on correcting neurochemical imbalances or circuit dysfunctions. While modern psychiatric practice has made significant advances through pharmacology and neuromodulation, such approaches often fail to address the psychological and existential dimensions of suffering like the loss of hope, lack of meaning or purpose, and diminished social connections that are central to conditions like depression. As this review has described, these are not abstract concepts but rather tangible experiences with clear neurobiological correlates. A purely biological approach that ignores the brain's capacity for meaning-making and self-transcendence is incomplete, leaving critical therapeutic avenues unexplored.

The future of mental healthcare requires a more sophisticated and holistic approach, one that can be described as integrative pluralism [

91]. This model strenuously avoids neuro-reductionist claims that spirituality is nothing but brain activity. Instead, it advocates for a multilevel framework that integrates insights from a wide spectrum of disciplines, from biochemistry and neurophysiology to psychology, sociology, and theology. Such a model recognizes that a complete understanding of human well-being requires acknowledging the validity of each level of analysis without granting ultimate explanatory authority to any single one. Ultimately, the future of effective and lasting mental healthcare lies in combining the best of conventional evidence-based treatments with adjunctive therapeutic approaches designed to restore hope, meaning, morality, and spiritual practice. These practices should not be considered merely supportive but as active, targeted interventions. They are potent drivers of neuroplasticity that optimize the function of cognitive and affective neural networks and help establish the profound and lasting resilience that is the true hallmark of mental health.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

WJT is a co-founder of IST, LLC and Diamond Therapeutics, Inc., as well as an inventor and co-inventor of neuromodulation devices and pharmacological methods for treating various neurologic and psychiatric disorders. The companies played no role in the preparation of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks numerous friends, family members, and colleagues for intellectual, spiritual, theological, and philosophical conversations and discussions that have helped motivate the preparation and framing of this manuscript. No funding was provided for the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Stachowicz, K.; Sowa-Kućma, M. The treatment of depression — searching for new ideas. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, D.; Rush, A.J.; Trivedi, M.H.; Fava, M.; Wisniewski, S.R. The STAR*D project results: A comprehensive review of findings. Current Psychiatry Reports 2007, 9, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigott, H.E.; Kim, T.; Xu, C.; Kirsch, I.; Amsterdam, J. What are the treatment remission, response and extent of improvement rates after up to four trials of antidepressant therapies in real-world depressed patients? A reanalysis of the STAR*D study's patient-level data with fidelity to the original research protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e063095. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.A.; Okun, M.S.; Scangos, K.W.; Mayberg, H.S.; de Hemptinne, C. Deep brain stimulation for refractory major depressive disorder: a comprehensive review. Molecular Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1075–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idlett-Ali, S.L.; Salazar, C.A.; Bell, M.S.; Short, E.B.; Rowland, N.C. Neuromodulation for treatment-resistant depression: Functional network targets contributing to antidepressive outcomes. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2023, 17, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newberg, A.B. The neuroscientific study of spiritual practices. Front Psychol 2014, 5, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, P.; Grafman, J. Advances in brain and religion studies: a review and synthesis of recent representative studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2024, 18, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller L, Balodis IM, McClintock CH, Xu J, Lacadie CM, Sinha R, et al. . Neural Correlates of Personalized Spiritual Experiences. Cerebral Cortex 2019, 29, 2331–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jedlicka, P.; Havenith, M.N. Religious and spiritual experiences from a neuroscientific and complex systems perspective. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2025, 177, 106319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenke CE, Kayser J, Svob C, Miller L, Alvarenga JE, Abraham K, et al. . Association of posterior EEG alpha with prioritization of religion or spirituality: A replication and extension at 20-year follow-up. Biological Psychology 2017, 124, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Wright, J.; Morgan, A.; Patton, G.; Reavley, N. Religiosity and spirituality in the prevention and management of depression and anxiety in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, A.W.; Koenig, H.G. Religion, spirituality and depression in prospective studies: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders 2019, 257, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, H.G. Research on Religion, Spirituality, and Mental Health: A Review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2009, 54, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmons, R.A.; Paloutzian, R.F. The Psychology of Religion. Annual Review of Psychology 2003, 54, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passie, T.; Warncke, J.; Peschel, T.; Ott, U. [Neurotheology: neurobiological models of religious experience]. Nervenarzt 2013, 84, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, I. Beyond the God Spot. The Way A review of Christian Spirituality published by the British Jesuits 2014, 53, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm, W.R. God Spots in the Brain: Nine Categories of Unasked, Unanswered Questions. Religions 2020, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapogiannis, D.; Deshpande, G.; Krueger, F.; Thornburg, M.P.; Grafman, J.H. Brain networks shaping religious belief. Brain Connect 2014, 4, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.F. Are religious experiences really localized within the brain? The promise, challenges, and prospects of neurotheology. The Journal of Mind and Behavior 2011, 223–249. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, R. The Limbic System and the Soul: Evolution and the Neuroanatomy of Religious Experience. Zygon® 2001, 36, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, M.; Paquette, V. Neural correlates of a mystical experience in Carmelite nuns. Neurosci Lett 2006, 405, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Lai, G. Spirituality and religion in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2008, 12, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, F. Ecstatic or Mystical Experience through Epilepsy. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2023, 35, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofori, I.; Bulbulia, J.; Shaver, J.H.; Wilson, M.; Krueger, F.; Grafman, J. Neural correlates of mystical experience. Neuropsychologia 2016, 80, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, N.P.; Missimer, J.; Seitz, R.J. Religious Experience and Emotion: Evidence for Distinctive Cognitive Neural Patterns. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2005, 15, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson MA, Schaper F, Cohen A, Siddiqi S, Merrill SM, Nielsen JA, et al. . A Neural Circuit for Spirituality and Religiosity Derived From Patients With Brain Lesions. Biol Psychiatry 2022, 91, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, F.; Craig, A.D. Ecstatic epileptic seizures: a potential window on the neural basis for human self-awareness. Epilepsy Behav 2009, 16, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrazana, E.; Cheng, J. St Theresa's dart and a case of religious ecstatic epilepsy. Cogn Behav Neurol 2011, 24, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persinger, M.A. Striking EEG profiles from single episodes of glossolalia and transcendental meditation. Percept Mot Skills 1984, 58, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, R.R.; Kose, S.; Abubakr, A. Temporal lobe discharges and glossolalia. Neurocase 2014, 20, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Aquili, E.G.; Newberg, A.B. Religous and Mystical States: A Neuropsychological Model. Zygon® 1993, 28, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberg, A.B.; Wintering, N.; Khalsa, D.S.; Roggenkamp, H.; Waldman, M.R. Meditation effects on cognitive function and cerebral blood flow in subjects with memory loss: a preliminary study. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 20, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgesi, C.; Aglioti, S.M.; Skrap, M.; Fabbro, F. The Spiritual Brain: Selective Cortical Lesions Modulate Human Self-Transcendence. Neuron 2010, 65, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, F.S.; Griffiths, R.R. Classic Hallucinogens and Mystical Experiences: Phenomenology and Neural Correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2018, 36, 393–430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newberg, A.B.; Wintering, N.A.; Morgan, D.; Waldman, M.R. The measurement of regional cerebral blood flow during glossolalia: a preliminary SPECT study. Psychiatry Res 2006, 148, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartledge M (2002): Charismatic Glossolalia: An empirical theological study. (New Critical Thinking in Theology and Biblical Studies Series). Ashgate.

- Azari NP, Nickel J, Wunderlich G, Niedeggen M, Hefter H, Tellmann L, et al. . Neural correlates of religious experience. Eur J Neurosci 2001, 13, 1649–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schjoedt, U. The Religious Brain: A General Introduction to the Experimental Neuroscience of Religion. Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 2009, 21, 310–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapogiannis, D.; Barbey, A.K.; Su, M.; Zamboni, G.; Krueger, F.; Grafman, J. Cognitive and neural foundations of religious belief. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 4876–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjoedt, U.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H.; Geertz, A.W.; Roepstorff, A. Highly religious participants recruit areas of social cognition in personal prayer. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2009, 4, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.; Lele, V.R.; Kuwert, T.; Langen, K.J.; Rota Kops, E.; Feinendegen, L.E. Changed pattern of regional glucose metabolism during yoga meditative relaxation. Neuropsychobiology 1990, 23, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum K, Braverman ER, Makale M, Zeine F, Roy AK, Khalsa J, et al. . Neurospirituality Connectome - Role in Neurology and Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS). EC Neurology 2025, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Elmholdt E-M, Skewes J, Dietz M, Møller A, Jensen MS, Roepstorff A, et al.. Reduced Pain Sensation and Reduced BOLD Signal in Parietofrontal Networks during Religious Prayer. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2017, 11, 2017.

- Charles SJ, Farias M, van Mulukom V, Saraswati A, Dein S, Watts F, et al. . Blocking mu-opioid receptors inhibits social bonding in rituals. Biol Lett 2020, 16, 20200485. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, S.J.; van Mulukom, V.; Brown, J.E.; Watts, F.; Dunbar, R.I.M.; Farias, M. United on Sunday: The effects of secular rituals on social bonding and affect. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0242546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch C (2025): The Neuroendocrine Effects of Religious Rituals. Encyclopedia of Religious Psychology and Behavior: Springer, pp 1-7.

- Feldman, R. Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans. Hormones and Behavior 2012, 61, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbrook, C.; Hahn-Holbrook, J.; Holt-Lunstad, J. Self-reported spirituality correlates with endogenous oxytocin. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 2015, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsch, C.B.; Ironson, G.; Szeto, A.; Kremer, H.; Schneiderman, N. ; Mendez AJ(2013): The Relationship of Spirituality Benefit Finding Other Psychosocial Variables to the Hormone Oxytocin in, H.I.V./.A.I.D.S. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp 137-162.

- Van Cappellen, P.; Way, B.M.; Isgett, S.F.; Fredrickson, B.L. Effects of oxytocin administration on spirituality and emotional responses to meditation. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2016, 11, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenberg, J.R. Oxytocin and our place in the universe. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology 2024, 20, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes DS, Skragge M, Döllinger L, Laukka P, Fischer H, Nilsson ME, et al. . Mixed support for a causal link between single dose intranasal oxytocin and spiritual experiences: opposing effects depending on individual proclivities for absorption. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2018, 13, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tønnesen, M.T.; Miani, A.; Pedersen, A.S.; Mitkidis, P.; Zak, P.J.; Winterdahl, M. Neuropeptide Y and religious commitment in healthy young women. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 2019, 31, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulett, J.M.; Johnstone, B.; Armer, J.M.; Deroche, C.; Millspaugh, R.; Millspaugh, J. Associations between religious and spiritual variables and neuroimmune activity in survivors of breast cancer: a feasibility study. Supportive Care in Cancer 2021, 29, 6421–6429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagnini, K.M.; Morozink Boylan, J.; Adams, M.; Masters, K.S. Multidimensional Religiousness and Spirituality Are Associated With Lower Interleukin-6 and C-Reactive Protein at Midlife: Findings From the Midlife in the United States Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2024, 58, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig HG, Pearce MJ, Nelson B, Shaw SF, Robins CJ, Daher NS, et al.. Religious vs. Conventional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Major Depression in Persons With Chronic Medical Illness: A Pilot Randomized Trial. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 2015, 203.

- Rickhi B, Moritz S, Reesal R, Xu TJ, Paccagnan P, Urbanska B, et al. . A Spirituality Teaching Program for Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 2011, 42, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenke CE, Kayser J, Miller L, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Weissman MM, et al. . Neuronal generators of posterior EEG alpha reflect individual differences in prioritizing personal spirituality. Biological Psychology 2013, 94, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrakowski, P.; Blaszkiewicz, M.; Skalski, S. Changes in the Electrical Activity of the Brain in the Alpha and Theta Bands during Prayer and Meditation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, P.; Durso, R.; Brown, A.; Harris, E. The chemistry of religiosity: Evidence from patients with Parkinson’s disease. Where God and science meet 2006, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, M. Introduction: Evidence for entheogen use in prehistory and world religions. Journal of Psychedelic Studies 2019, 3, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, W.A. Entheogens in the study of religious experiences: Current status. Journal of Religion and Health 2005, 44, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruck, C.A.; Bigwood, J.; Staples, D.; Ott, J.; Wasson, R.G. Entheogens. Journal of psychedelic drugs 1979, 11, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstad, P.G. Entheogenic spirituality: Exploring spiritually motivated entheogen use among modern westerners. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research 2018, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Richards, W.A.; McCann, U.; Jesse, R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology 2006, 187, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W.; Richards, W.A.; Richards, B.D.; McCann, U.; Jesse, R. Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: immediate and persisting dose-related effects. Psychopharmacology 2011, 218, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Richards WA, Richards BD, Jesse R, MacLean KA, et al. . Psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2017, 32, 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Barsuglia J, Davis AK, Palmer R, Lancelotta R, Windham-Herman A-M, Peterson K, et al. . Intensity of mystical experiences occasioned by 5-MeO-DMT and comparison with a prior psilocybin study. Frontiers in psychology 2018, 9, 2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, K.; Knight, G.; Rucker, J.J.; Cleare, A.J. Psychedelics, Mystical Experience, and Therapeutic Efficacy: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carhart-Harris RL, Erritzoe D, Williams T, Stone JM, Reed LJ, Colasanti A, et al. . Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 2138–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carhart-Harris RL, Roseman L, Bolstridge M, Demetriou L, Pannekoek JN, Wall MB, et al. . Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso JJ, Perkins D, Ruffell S, Lawrence AJ, Hoyer D, Jacobson LH, et al. . Default mode network modulation by psychedelics: a systematic review. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 26, 155–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, Cosimano MP, Sepeda ND, Johnson MW, et al. . Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry 2021, 78, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, Arden PC, Baker A, Bennett JC, et al. . Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Griffiths, R.R. Potential therapeutic effects of psilocybin. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, D.C.; Syed, S.A.; Flynn, L.T.; Safi-Aghdam, H.; Cozzi, N.V.; Ranganathan, M. Exploratory study of the dose-related safety, tolerability, and efficacy of dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in healthy volunteers and major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 1854–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, S.A. Administration of N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in psychedelic therapeutics and research and the study of endogenous DMT. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 1749–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, et al. . Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol 2016, 30, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnayder, S.; Ameli, R.; Sinaii, N.; Berger, A.; Agrawal, M. Psilocybin-assisted therapy improves psycho-social-spiritual well-being in cancer patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 2023, 323, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strassman, R.J. Human psychopharmacology of N, N-dimethyltryptamine. Behavioural brain research 1995, 73, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassman R (2014): DMT and the soul of prophecy: A new science of spiritual revelation in the Hebrew Bible. Simon and Schuster.

- Davis, A.K.; Clifton, J.M.; Weaver, E.G.; Hurwitz, E.S.; Johnson, M.W.; Griffiths, R.R. Survey of entity encounter experiences occasioned by inhaled N, N-dimethyltryptamine: Phenomenology, interpretation, and enduring effects. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2020, 34, 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, S.A. N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an Endogenous Hallucinogen: Past, Present, and Future Research to Determine Its Role and Function. Front Neurosci 2018, 12, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean JG, Liu T, Huff S, Sheler B, Barker SA, Strassman RJ, et al. . Biosynthesis and extracellular concentrations of N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in mammalian brain. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 9333. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, J.H.; Bouso, J.C. Significance of mammalian N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT): A 60-year-old debate. J Psychopharmacol 2022, 36, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knegtering, H.; Bruggeman, R.; Spoelstra, S.K. Spirituality as a Therapeutic Approach for Severe Mental Illness: Insights from Neural Networks. Religions 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetz, M.; Toews, J. Clinical Implications of Research on Religion, Spirituality, and Mental Health. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2009, 54, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefti, R. Integrating Religion and Spirituality into Mental Health Care, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. Religions 2011, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seybold, K.S.; Hill, P.C. The Role of Religion and Spirituality in Mental and Physical Health. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2001, 10, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberg, A.B. Neurotheology: Practical Applications with Regard to Integrative Psychiatry. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2025, 27, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaitán, L.M.; Castresana, J.S. Is an Integrative Model of Neurotheology Possible? Religions 2021, 12, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Brain Regions Involved in Religious and Spiritual Practices and Experiences. Lateral (left) and sagittal (right) schematic illustrations of the brain show anatomical regions involved in regulating the neurocognitive and psychosomatic manifestations of religious and spiritual (R/S) practice and experience. Theory of Mind (ToM) networks are indicated by purple showing the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), precuneus, and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) contribute to interpreting divine intent and spiritual guidance. Cognitive Control networks are indicated by green show the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) involved in reappraisal and top-down regulation of cognitive and neurobehavioral functions during R/S practices, supernatural experiences, and self-referential awareness. Reward and Evaluation circuits are indicated by pink show the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and nucleus accumbens (NAcc), which are regions encoding value, salience, and affective meaning to established or newly formed R/S beliefs. Semantic Processing regions are indicated by orange and show the inferior frontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus (STG), and temporopolar cortex that retrieve and integrate R/S concepts stored in semantic and episodic memory. Conflict Detection regions are indicated by yellow and highlight dorsal/rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which detects conflict between R/S beliefs and values with competing stimuli to bias morality and behavioral adjustment. Multisensory Integration regions are indicated by blue and show posterior parietal cortex and TPJ, which integrate multimodal sensory inputs contributing to the reception of transcendent R/S experiences. Figure adapted from Reference [

7].

Figure 1.

Brain Regions Involved in Religious and Spiritual Practices and Experiences. Lateral (left) and sagittal (right) schematic illustrations of the brain show anatomical regions involved in regulating the neurocognitive and psychosomatic manifestations of religious and spiritual (R/S) practice and experience. Theory of Mind (ToM) networks are indicated by purple showing the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), precuneus, and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) contribute to interpreting divine intent and spiritual guidance. Cognitive Control networks are indicated by green show the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) involved in reappraisal and top-down regulation of cognitive and neurobehavioral functions during R/S practices, supernatural experiences, and self-referential awareness. Reward and Evaluation circuits are indicated by pink show the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and nucleus accumbens (NAcc), which are regions encoding value, salience, and affective meaning to established or newly formed R/S beliefs. Semantic Processing regions are indicated by orange and show the inferior frontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus (STG), and temporopolar cortex that retrieve and integrate R/S concepts stored in semantic and episodic memory. Conflict Detection regions are indicated by yellow and highlight dorsal/rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which detects conflict between R/S beliefs and values with competing stimuli to bias morality and behavioral adjustment. Multisensory Integration regions are indicated by blue and show posterior parietal cortex and TPJ, which integrate multimodal sensory inputs contributing to the reception of transcendent R/S experiences. Figure adapted from Reference [

7].

Figure 2.

Integrated Spiritual Neurotherapeutics Model for Improving Mental Health Outcomes. Schematic depicting hypothesized pathways by which diverse religious and spiritual (R/S) practices, such as contemplative (prayer and meditation), relational (forgiveness, gratitude, confession, altruistic service, and congregational worship), and embodied/ritual (chanting, singing, glossolalia, synchronized movement, fasting, and pilgrimage) engage large-scale brain networks. These neural networks include the Default Mode Network (DMN), Salience Network (SN), frontoparietal control network (CEN), limbic/temporal systems, and temporoparietal/Theory-of-Mind (ToM) networks. Clinical and therapeutic embodiments including religious counseling, spiritually integrated CBT, and supervised psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) recruit these same brain networks and mechanisms. The downstream cognitive–affective effects of modulating these networks during R/S practices or integrated therapies include reduced rumination, decreased ego-centric processing, enhanced cognitive control and reappraisal, and increased connection, purpose, and meaning. Putative molecular pathways and outcomes include serotoninergic (5-HT, 5-HT2A) mediated neuroplasticity and self-transcendence, dopamine (DA) mediated reward and motivation, μ-opioid/oxytocin regulated bonding and trust, and neuroimmune axis modulation of sympathetic tone and inflammation. The framework highlights safeguards mitigating religious struggle, punitive beliefs, conflict, and isolation by promoting compassion-based, culturally humble approaches. Translational implications suggest mental health approaches to consider and include R/S counseling, spiritually informed CBT, and professional R/S integration support if considering PAT. Convergent biomarkers can be incorporated to monitor and track therapeutic efficacy of R/S integration by quantifying data from trait markers (posterior EEG alpha; R/S importance), state markers (mystical intensity, meaning, forgiveness, awe), wearable biosensors (HRV, sleep, EEG), chemical biomarkers (cortisol, salivary α-amylase, IL-6, CRP), and clinical outcomes (depression, stress, anxiety, and quality of life measures). Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; PAT, psychedelic-assisted therapy; HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; CRP, C-reactive protein; HRV, heart rate variability; SAA, salivary alpha-amylase; 5-HT2A, serotonin receptor type 2A.

Figure 2.