Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

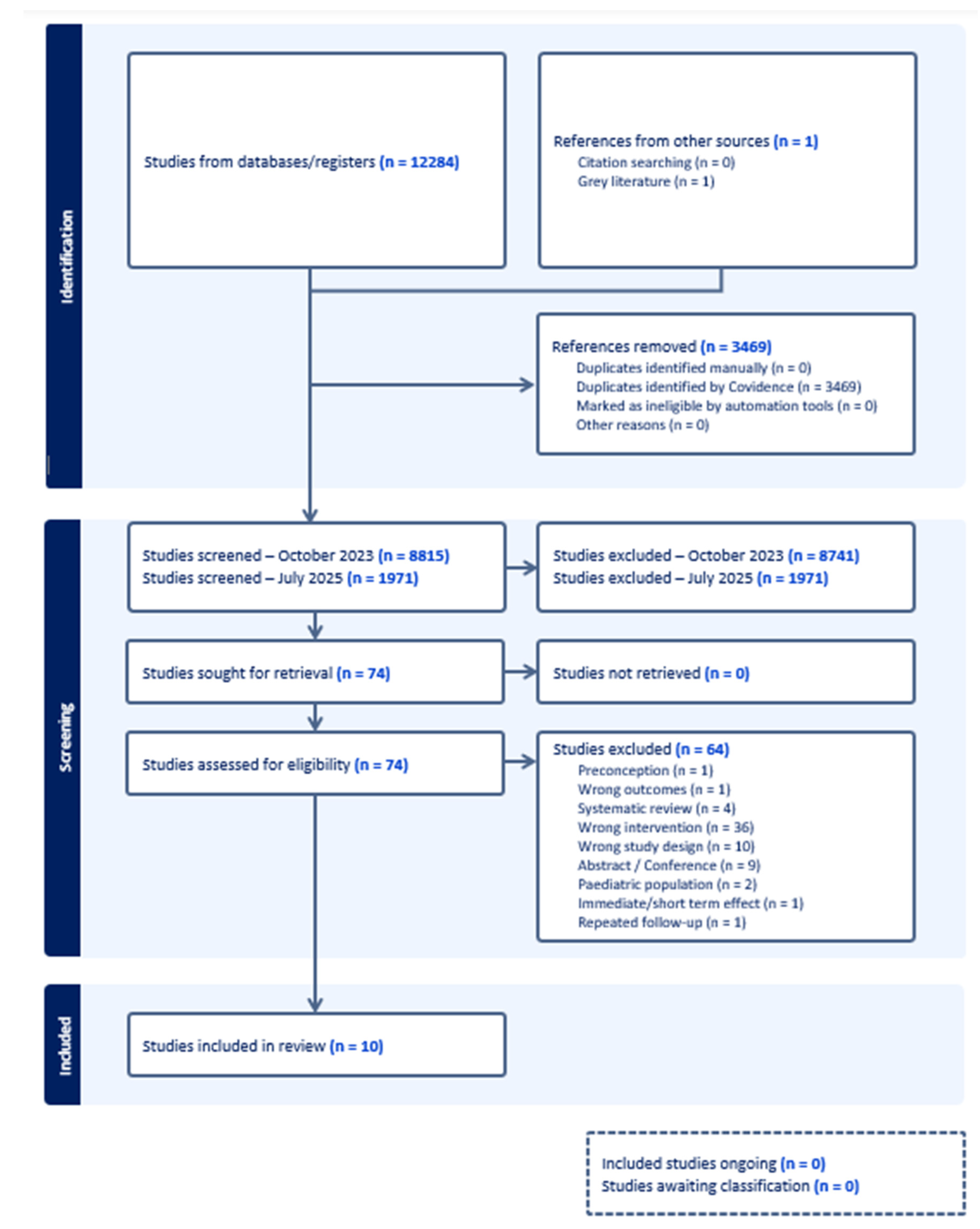

Methods

Data Sources and Search Strategies

Eligibility Criteria

Outcome Measures

Study Selection and Screening

Data Extraction

Assessment of Risk of Bias

Data Synthesis

Results

Study Characteristics

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Long-Term Effects of Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation on Cognitive Outcomes

Maternal Supplementation

Infant and Young Child Supplementation

Combined Maternal and Child Supplementation

Effect Direction Results for Developmental Outcomes in the Included Studies

Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

Conclusion

Public Health Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Conflict of Interest

Disclaimer

References

- WHO. Micronutrients. Availabe online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/micronutrients#tab=tab_1.

- Benton, D. The influence of dietary status on the cognitive performance of children. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 457-470, . [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Taneja, S. Zinc and cognitive development. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 85 Suppl 2, S139-145, . [CrossRef]

- de Rooij, S.R.; Wouters, H.; Yonker, J.E.; Painter, R.C.; Roseboom, T.J. Prenatal undernutrition and cognitive function in late adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 16881-16886, . [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A.; Nelson, C.A. Developmental science and the media. Early brain development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 5-15, doi:https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.56.1.5.

- Alem, A.Z.; Efendi, F.; McKenna, L.; Felipe-Dimog, E.B.; Chilot, D.; Tonapa, S.I.; Susanti, I.A.; Zainuri, A. Prevalence and factors associated with anemia in women of reproductive age across low- and middle-income countries based on national data. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20335, . [CrossRef]

- WHO. Anaemia. Availabe online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anaemia.

- Tau, G.Z.; Peterson, B.S. Normal Development of Brain Circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 147-168, . [CrossRef]

- Gernand, A.D.; Schulze, K.J.; Stewart, C.P.; West, K.P., Jr.; Christian, P. Micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy worldwide: health effects and prevention. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 2016, 12, 274-289, . [CrossRef]

- Lh, A.; Ahluwalia, N. Improving Iron Status Through Diet The Application of Knowledge Concerning Dietary Iron Bioavailability in Human Populations.

- Keats, E.C.; Akseer, N.; Thurairajah, P.; Cousens, S.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Global Young Women's Nutrition Investigators, G. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation in pregnant adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 141-156, . [CrossRef]

- Berry, R.J.; Li, Z.; Erickson, J.D.; Li, S.; Moore, C.A.; Wang, H.; Mulinare, J.; Zhao, P.; Wong, L.Y.; Gindler, J., et al. Prevention of neural-tube defects with folic acid in China. China-U.S. Collaborative Project for Neural Tube Defect Prevention. The New England journal of medicine 1999, 341, 1485-1490, . [CrossRef]

- De-Regil, L.M.; Fernández-Gaxiola, A.C.; Dowswell, T.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Effects and safety of periconceptional folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2010, Cd007950. [CrossRef]

- Imbard, A.; Benoist, J.F.; Blom, H.J. Neural tube defects, folic acid and methylation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4352-4389, . [CrossRef]

- Stiles, J.; Jernigan, T.L. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2010, 20, 327-348, . [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2016.

- WHO. WHO 2020 Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; 2020.

- WHO. WHO antenatal care recommendations for a positive pregnancy experience. Nutritional interventions update: Multiple micronutrient supplements during pregnancy; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020.

- Biesalski Hans, K.; Jana, T. Micronutrients in the life cycle: Requirements and sufficient supply. NFS Journal 2018, 11, 1-11, . [CrossRef]

- Suchdev, P.S.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; De-Regil, L.M. Multiple micronutrient powders for home (point-of-use) fortification of foods in pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, . [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guideline: Use of multiple micronutrient powders for point-of-use fortification of foods consumed by pregnant women; World Health Organization: 2016.

- WHO. Guideline: Use of multiple micronutrient powders for point-of-use fortification of foods consumed by infants and young children aged 6–23 months and children aged 2–12 years; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Devakumar, D.; Fall, C.H.; Sachdev, H.S.; Margetts, B.M.; Osmond, C.; Wells, J.C.; Costello, A.; Osrin, D. Maternal antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation for long-term health benefits in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 90, . [CrossRef]

- Leung, B.M.; Wiens, K.P.; Kaplan, B.J. Does prenatal micronutrient supplementation improve children's mental development? A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011, 11, 12, . [CrossRef]

- Geletu, A.; Lelisa, A.; Baye, K. Provision of low-iron micronutrient powders on alternate days is associated with lower prevalence of anaemia, stunting, and improved motor milestone acquisition in the first year of life: A retrospective cohort study in rural Ethiopia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12785, . [CrossRef]

- Prado, E.L.; Alcock, K.J.; Muadz, H.; Ullman, M.T.; Shankar, A.H. Maternal multiple micronutrient supplements and child cognition: a randomized trial in Indonesia. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e536-546, . [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Yue, A.; Zhou, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Martorell, R.; Medina, A.; Rozelle, S.; Sylvia, S. The effect of a micronutrient powder home fortification program on anemia and cognitive outcomes among young children in rural China: a cluster randomized trial. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 738, . [CrossRef]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: Review Articles, Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analysis, and the Updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 Guidelines. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e934475, . [CrossRef]

- Keats, E.C.; Haider, B.A.; Tam, E.; Bhutta, Z.A. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, Cd004905, . [CrossRef]

- Fantom, N.; Serajuddin, U. The World Bank’s Classification of Countries by Income. 2016.

- Prado, E.L.; Sebayang, S.K.; Apriatni, M.; Adawiyah, S.R.; Hidayati, N.; Islamiyah, A.; Siddiq, S.; Harefa, B.; Lum, J.; Alcock, K.J., et al. Maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation and other biomedical and socioenvironmental influences on children's cognition at age 9-12 years in Indonesia: follow-up of the SUMMIT randomised trial. The Lancet. Global health 2017, 5, e217-e228, . [CrossRef]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins;, J.P., Green;, S., Eds. 2011.

- Christian, P.; Murray-Kolb, L.E.; Khatry, S.K.; Katz, J.; Schaefer, B.A.; Cole, P.M.; Leclerq, S.C.; Tielsch, J.M. Prenatal micronutrient supplementation and intellectual and motor function in early school-aged children in Nepal. JAMA 2010, 304, 2716-2723, . [CrossRef]

- Murray-Kolb, L.E.; Khatry, S.K.; Katz, J.; Schaefer, B.A.; Cole, P.M.; LeClerq, S.C.; Morgan, M.E.; Tielsch, J.M.; Christian, P. Preschool Micronutrient Supplementation Effects on Intellectual and Motor Function in School-aged Nepalese Children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 404-410, . [CrossRef]

- Yousafzai, A.K.; Obradović, J.; Rasheed, M.A.; Rizvi, A.; Portilla, X.A.; Tirado-Strayer, N.; Siyal, S.; Memon, U. Effects of responsive stimulation and nutrition interventions on children's development and growth at age 4 years in a disadvantaged population in Pakistan: a longitudinal follow-up of a cluster-randomised factorial effectiveness trial. The Lancet. Global health 2016, 4, e548-558, . [CrossRef]

- Christian, P.; Morgan, M.E.; Murray-Kolb, L.; LeClerq, S.C.; Khatry, S.K.; Schaefer, B.; Cole, P.M.; Katz, J.; Tielsch, T. Preschool Iron-Folic Acid and Zinc Supplementation in Children Exposed to Iron-Folic Acid in Utero Confers No Added Cognitive Benefit in Early School-Age12. The Journal of Nutrition 2011, 141, 2042-2048, . [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, L.E.; Putnick, D.L.; Zavaleta, N.; Lazarte, F.; Albornoz, C.; Chen, P.; Dipietro, J.A.; Bornstein, M.H. Maternal gestational zinc supplementation does not influence multiple aspects of child development at 54 mo of age in Peru. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2010, 92, 130-136, . [CrossRef]

- Sudfeld, C.R.; Manji, K.P.; Darling, A.M.; Kisenge, R.; Kvestad, I.; Hysing, M.; Belinger, D.C.; Strand, T.A.; Duggan, C.P.; Fawzi, W.W. Effect of antenatal and infant micronutrient supplementation on middle childhood and early adolescent development outcomes in Tanzania. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 1283-1290, . [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Qi, Q.; Huang, L.; Andegiorgish, A.K.; Elhoumed, M.; Cheng, Y.; Dibley, M.J.; Sudfeld, C.R., et al. Effects of antenatal micronutrient supplementation regimens on adolescent emotional and behavioral problems: A 14-year follow-up of a double-blind, cluster-randomized controlled trial. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2023, 42, 129-135, . [CrossRef]

- Dulal, S.; Liégeois, F.; Osrin, D.; Kuczynski, A.; Manandhar, D.S.; Shrestha, B.P.; Sen, A.; Saville, N.; Devakumar, D.; Prost, A. Does antenatal micronutrient supplementation improve children's cognitive function? Evidence from the follow-up of a double-blind randomised controlled trial in Nepal. BMJ global health 2018, 3, e000527, . [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zeng, L.; Elhoumed, M.; He, G.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, W.; Li, D.; Tsegaye, S., et al. Association of Antenatal Micronutrient Supplementation With Adolescent Intellectual Development in Rural Western China: 14-Year Follow-up From a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatrics 2018, 172, 832-841, . [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yan, H.; Zeng, L.; Cheng, Y.; Liang, W.; Dang, S.; Wang, Q.; Tsuji, I. Effects of Maternal Multimicronutrient Supplementation on the Mental Development of Infants in Rural Western China: Follow-up Evaluation of a Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e685-e692, . [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zeng, L.; Wang, D.; Yang, W.; Dang, S.; Zhou, J.; Yan, H. Prenatal Micronutrient Supplementation Is Not Associated with Intellectual Development of Young School-Aged Children. The Journal of nutrition 2015, 145, 1844-1849, . [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, P. Iron and zinc interactions in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 442s-446s, . [CrossRef]

- Olivares, M.; Pizarro, F.; Ruz, M. New insights about iron bioavailability inhibition by zinc. Nutrition 2007, 23, 292-295, . [CrossRef]

- Nyaradi, A.; Li, J.; Hickling, S.; Foster, J.; Oddy, W. The role of nutrition in children's neurocognitive development, from pregnancy through childhood. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, . [CrossRef]

- Helland, I.B.; Smith, L.; Blomén, B.; Saarem, K.; Saugstad, O.D.; Drevon, C.A. Effect of supplementing pregnant and lactating mothers with n-3 very-long-chain fatty acids on children's IQ and body mass index at 7 years of age. Pediatrics 2008, 122, e472-479, . [CrossRef]

- Aboud, F.E.; Yousafzai, A.K. Global health and development in early childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 433-457, . [CrossRef]

- Nores, M.; Barnett, W.S. Benefits of early childhood interventions across the world: (Under) Investing in the very young. Economics of Education Review 2010, 29, 271-282, . [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.M.; Yousafzai, A.K. A meta-analysis of nutrition interventions on mental development of children under-two in low- and middle-income countries. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, . [CrossRef]

- Eilander, A.; Gera, T.; Sachdev, H.S.; Transler, C.; van der Knaap, H.C.; Kok, F.J.; Osendarp, S.J. Multiple micronutrient supplementation for improving cognitive performance in children: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 115-130, . [CrossRef]

- Benton, D. Micro-nutrient supplementation and the intelligence of children. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2001, 25, 297-309, . [CrossRef]

- Benton, D. Vitamins and neural and cognitive developmental outcomes in children. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2012, 71, 14-26, . [CrossRef]

- Nutrition Research Facility. Multiple micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy, lactation, and early childhood and the long-term child development: Systematic literature review; Brussels, 2024.

- Merialdi, M.; Caulfield, L.E.; Zavaleta, N.; Figueroa, A.; Dominici, F.; DiPietro, J.A. Randomized controlled trial of prenatal zinc supplementation and the development of fetal heart rate. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 190, 1106-1112, . [CrossRef]

- Merialdi, M.; Caulfield, L.E.; Zavaleta, N.; Figueroa, A.; Costigan, K.A.; Dominici, F.; Dipietro, J.A. Randomized controlled trial of prenatal zinc supplementation and fetal bone growth. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2004, 79, 826-830, . [CrossRef]

- Christian, P.; Khatry, S.K.; Katz, J.; Pradhan, E.K.; LeClerq, S.C.; Shrestha, S.R.; Adhikari, R.K.; Sommer, A.; West, K.P., Jr. Effects of alternative maternal micronutrient supplements on low birth weight in rural Nepal: double blind randomised community trial. BMJ 2003, 326, 571, . [CrossRef]

- Christian, P.; West, K.P.; Khatry, S.K.; Leclerq, S.C.; Pradhan, E.K.; Katz, J.; Shrestha, S.R.; Sommer, A. Effects of maternal micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant mortality: a cluster-randomized trial in Nepal. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 1194-1202, . [CrossRef]

- Osrin, D.; Vaidya, A.; Shrestha, Y.; Baniya, R.B.; Manandhar, D.S.; Adhikari, R.K.; Filteau, S.; Tomkins, A.; de L Costello, A.M. Effects of antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation on birthweight and gestational duration in Nepal: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2005, 365, 955-962, . [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.H.; Jahari, A.B.; Sebayang, S.K.; Aditiawarman; Apriatni, M.; Harefa, B.; Muadz, H.; Soesbandoro, S.D.; Tjiong, R.; Fachry, A., et al. Effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant death in Indonesia: a double-blind cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2008, 371, 215-227, . [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, W.W.; Msamanga, G.I.; Urassa, W.; Hertzmark, E.; Petraro, P.; Willett, W.C.; Spiegelman, D. Vitamins and Perinatal Outcomes among HIV-Negative Women in Tanzania. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1423-1431, . [CrossRef]

- Lingxia, Z.; Yue, C.; Shaonong, D.; Hong, Y.; Michael, J.D.; Suying, C.; Lingzhi, K. Impact of micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy on birth weight, duration of gestation, and perinatal mortality in rural western China: double blind cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008, 337, a2001, . [CrossRef]

- Tielsch, J.M.; Khatry, S.K.; Stoltzfus, R.J.; Katz, J.; LeClerq, S.C.; Adhikari, R.; Mullany, L.C.; Shresta, S.; Black, R.E. Effect of routine prophylactic supplementation with iron and folic acid on preschool child mortality in southern Nepal: community-based, cluster-randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2006, 367, 144-152, . [CrossRef]

- Tielsch, J.M.; Khatry, S.K.; Stoltzfus, R.J.; Katz, J.; LeClerq, S.C.; Adhikari, R.; Mullany, L.C.; Black, R.; Shresta, S. Effect of daily zinc supplementation on child mortality in southern Nepal: a community-based, cluster randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 1230-1239, . [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.M.; Manji, K.P.; Kisenge, R.; Aboud, S.; Spiegelman, D.; Fawzi, W.W.; Duggan, C.P. Daily Zinc but Not Multivitamin Supplementation Reduces Diarrhea and Upper Respiratory Infections in Tanzanian Infants: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2153-2160, . [CrossRef]

- Yousafzai, A.K.; Rasheed, M.A.; Rizvi, A.; Armstrong, R.; Bhutta, Z.A. Effect of integrated responsive stimulation and nutrition interventions in the Lady Health Worker programme in Pakistan on child development, growth, and health outcomes: a cluster-randomised factorial effectiveness trial. Lancet 2014, 384, 1282-1293, . [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study design and sample | Outcomes | Intervention/Duration | Measures | Results | SMD [95% Confidence Interval] |

| Supplementation of women during pregnancy and lactation | ||||||

| Caulfield et al. [37] | RCT 184 children (Peru, 2003-2010) |

(1)cognitive development, (3)behavioural development 4–5 years |

Zinc + folic acid + iron vs. IFA Daily, 10-16 gestational week until 1 month postpartum |

(1)Wechsler Preschool & Primary Scale of Intelligence | ↔1,3 | -0.04 [-0.33, 0.25] |

| (1)Language development, bear story | 0.02 [-0.27, 0.32] | |||||

| (1)Number concepts, counting game | 0.02 [-0.28, 0.32] | |||||

| (1)Goodenough & Harris Draw-a-Person Test | -0.11 [-0.42, 0.19] | |||||

| (1)Interpersonal understanding, friendship interview | -0.16 [-0.47, 0.15] | |||||

| (3)Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales Communication Daily living skills Socialization Motor skills |

-0.11 [-0.40, 0.18] 0.06 [-0.23, 0.35] 0.06 [-0.23, 0.36] 0.04 [-0.25, 0.34] |

|||||

| (3)Preschool Behaviour Questionnaire Internalizing Externalizing |

0.13 [-0.16, 0.42] 0.06 [-0.23, 0.35] |

|||||

| Christian et al. [33] | Cluster RCT 281 children (Nepal, 2007-2009) |

(1)cognitive development, (2)motor development 7–9 years |

Zinc + folic acid + iron + VA vs. IFA + VA Daily supplementation from 11 (±5.1) gestational week until up to 12 weeks postpartum |

(1)The Universal Non-Verbal Intelligence Test (UNIT)a | ↔1a ↔1b ↓1c ↓1d ↓2a ↓2b |

-0.17 [-0.41, 0.08] |

| (1)Executive function Go/No-go testb Stroop test(proportion who failed)c Backward digit spand |

-0.22 [-0.46, 0.03] 0.33 [0.09, 0.57] -0.33 [-0.57, -0.08] |

|||||

| (2)The Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC)a* | 0.33 [0.08, 0.57] | |||||

| (2)Finger-tapping testb | -0.41 [-0.66, -0.17] | |||||

| Christian et al. [33] | Cluster RCT 321 children (Nepal, 2007-2009) |

(1)cognitive development, (2)motor development 7–9 years |

MMNs + VA vs. IFA + VA Daily supplementation from 11 (±5.1) gestational week until up to 12 weeks postpartum |

(1)The Universal Non-Verbal Intelligence Test (UNIT)a | ↓1a ↔1b ↔1c ↓1d ↓2a ↓2b |

-0.26 [-0.49, -0.02] |

| (1)Executive function Go/No-go testb Stroop test(proportion who failed)c Backward digit spand |

-0.00 [-0.24, 0.23] 0.20 [-0.03, 0.44] -0.36 [-0.60, -0.13] |

|||||

| (2)The Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC)a* | 0.32 [0.09, 0.56] | |||||

| (2)Finger-tapping testb | -0.45 [-0.69, -0.22] | |||||

| Dulal et al. [40] | RCT 813 young adolescents (Nepal, 2015-2016) |

(1)cognitive development 12 years |

UNIMMAP MMNs vs. IFA Daily supplementation between 12 weeks gestation until childbirth. |

(1)The Universal Non-Verbal Intelligence Test (UNIT) | ↔1 | 0.09 [-0.05, 0.23] |

| (1)Executive function using a counting Stroop test | 0.10 [-0.04, 0.24] | |||||

| Prado et al. [31] | Cluster RCT 2879 children and young adolescents (Indonesia, 2012-2014) |

(1)cognitive development, (2)motor development, (3)behavioural development 9–12 years |

UNIMMAP MMN vs. IFA Daily supplementation between enrolment (34% in 1st trimester, 43% in 2nd trimester, and 23% in 3rd trimester) and 3 months postpartum |

(1)General intellectual abilitya (1)Declarative memoryb (1)Procedural memoryc (1)Executive functiond (1)Academic achievemente |

↔1a ↔1b ↑1c ↔1d ↔1e ↔2 ↔3 |

0.09 [-0.03, 0.22] 0.01 [-0.09, 0.11] 0.11 [0.01, 0.20] 0.07 {-0.04, 0.19] 0.08 [-0.05, 0.21] |

| (2)Fine motor dexterity | -0.07 [-0.16, 0.02] | |||||

| (3)Socio-emotional health | 0.06 [-0.04, 0.16] | |||||

| Sudfeld et al. [38] | RCT 446 young adolescents (Tanzania, 2015-2017) |

(1)cognitive development, (3)behavioural development 11–14 years |

IFA + MVs vs. IFA + Placebo Daily supplementation from 12-27 gestational weeks to 6 weeks after childbirth |

(1)General Intelligencea (Atlantis, Footsteps, Hand movement, Kilifi naming test, Koh’s block design test, Story completion, and verbal fluency) | ↔1, 3 | -0.02 [-0.20, 0.17] |

| (1)Executive functionb (Literacy, Numeracy, NOGO, People search, ROCF copy, ROCF recall, and Shift) | 0.00 [-0.19, 0.19] | |||||

| (3)Mental health.(SDQ and the Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) to assess mental health) | 0.05 [-0.14, 0.23] | |||||

| Zhu et al. [39,41] | Cluster RCT 1385 children and young adolescents (China, 2016) |

(1)cognitive development, (3)behavioural development 10–14 years |

UNIMMAP MMN vs. IFA Daily supplementation from 13.8 (±5.8) gestational weeks to childbirth. |

(1)Adolescent full-scale intelligence quotient and aspects of verbal comprehension, working memory, perceptual reasoning, and processing speed indexes were assessed by the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children | ↑1 ↔3 |

0.13 [0.03, 0.24] |

| (3)Internalizing, externalizing, and total behaviour problem scores | 0.05 [-0.06, 0.16] | |||||

| Supplementation of infants and young children | ||||||

| Murray-Kolb et al. [34] | Cluster RCT 377 children (Nepal, 2007-2009) |

(1)cognitive development, (2)motor development 7–9 years |

IFAZn vs. Placebo Daily supplementation from 12–35 months of age (length of supplementation depended on age at enrolment) |

(1)The Universal Non-Verbal Intelligence Test (UNIT)a | ↔1a,1c,1d ↑1b ↔2a,2b |

0.11 [-0.10, 0.31] |

| (1)Stroop test (proportion who failed)b | -0.29 [-0.50, -0.09] | |||||

| (1)Backward digit spanc | 0.18 [-0.02, 0.39] | |||||

| (1)Go/No-Go testd | -0.13 [-0.34, 0.07] | |||||

| (2)The Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC)a* | -0.12 [-0.32, 0.08] | |||||

| (2)Finger-tappingb | 0.18 [-0.02, 0.39] | |||||

| Sudfeld et al. [38] | RCT 365 children (Tanzania, 2015-2017) |

(1)cognitive development, (3)behavioural development 6–8 years |

MVs vs. No MVs Daily supplementation for 18 months. 1-6 months old infants received one dose daily. Infants received two doses daily from 7 mos. 2x2 Factorial design provided (1) Zn+MVs (n=66); (2) Zn (n=101); (3) MVs (n=106); (4) Placebo (n=92). The analysis of MVs (group 1 and 3) vs. no MVs (group 2 and 4) |

(1)General Intelligencea (Atlantis, Footsteps, Hand movement, Kilifi naming test, Koh’s block design test, Story completion, and verbal fluency) | ↔1,3 | 0.00 [-0.21, 0.21] |

| (1)Executive functionb (Literacy, Numeracy, NOGO, People search, ROCF copy, ROCF recall, and Shift) | 0.00 [-0.21, 0.21] | |||||

| (3)Mental health.(SDQ and the Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) to assess mental health) | 0.08 [-0.10, 0.26] | |||||

| Yousafzai et al. [35] | Cluster RCT 1302 children (Pakistan, 2013) |

(1)cognitive development, (2)motor development, (3)behavioural development 4 years |

MNP vs. No MNP Daily supplementation from (6 months –24 months). |

(1)Cognitive capacity including Intelligent quotienta Executive functionb Pre-academic skillsc |

↔1a,1b,2,3 ↑1c |

-0.10 [-0.21, 0.02] -0.03 [-0.15, 0.09] 0.16 [0.05, 0.27] |

| (2)Motor development | 0.11 [-0.01, 0.24] | |||||

| (3)Social-emotional development Pro-social behaviours Behavioural problems |

-0.09 [-0.20, 0.01] -0.02 [-0.13, 0.09] |

|||||

| Supplementation of women during pregnancy and lactation and of infants and young children | ||||||

| Christian et al. [36] | Cluster RCT 223 children (Nepal, 2007-2009) |

(1)cognitive development, (2)motor development 7–9 years |

M-IFAZn C-IFAZn vs. M-IFA C-Pl Daily maternal supplementation from 11 (±5.1) gestational week until up to 12 weeks postpartum, and preschool daily supplementation from 12–35 months of age (length of supplementation depended on age at enrolment) |

(1)The Universal Non-Verbal Intelligence Test (UNIT)a | ↔1a, 1d ↓1b ↓1c ↓2a ↓2b |

-0.16 [-0.43, 0.10] |

| (1)Stroop test (proportion who failed)b | 0.40 [0.13, 0.66] | |||||

| (1)Backward digit spanc | -0.44 [-0.71, -0.18] | |||||

| (1)Go/no-go testd | -0.22 [-0.48, 0.05] | |||||

| (2)The Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC)a* | 0.34 [0.07, 0.61] | |||||

| (2)Finger-tappingb | -0.46 [-0.72, -0.19] | |||||

| Vitamin A (µg RAE) | B1 (mg) | B2 (mg) | B3 (mg) | B6 (mg) | B12 (µg) | Folic acid (µg) | Vit. C (mg) | Vit. D (µg) | Vit. E (mg) | Iron (mg) | Zinc (mg) | Cu (mg) | I (µg) | Se (µg) | |

| Supplementation of women during pregnancy and lactation | |||||||||||||||

|

Caulfield et al. [37] IFAZn |

250 | 60 | 25 | ||||||||||||

|

Christian et al. [33] IFAZn |

1000 | 400 | 60 | 30 | |||||||||||

|

Christian et al. [33] MMNs1 |

1000 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 20 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 400 | 100 | 10 | 10 | 60 | 30 | 2.0 | ||

|

Dulal et al. [40] UNIMMAP MMNs |

800 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 18 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 400 | 70 | 5.0 | 10 | 30 | 15 | 2.0 | 150 | 65 |

|

Prado et al. [31] UNIMMAP MMNs |

800 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 18 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 400 | 70 | 200 (IU) | 10 | 30 | 15 | 2.0 | 150 | 65 |

|

Sudfeld et al. [38] MVs |

20 | 20 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 800 | 500 | 30 | |||||||

|

Zhu et al. [39,41] UNIMMAP MMNs |

800 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 18 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 400 | 70 | 5.0 | 10 | 30 | 15 | 2.0 | 150 | 65 |

| Supplementation of infants and young children | |||||||||||||||

|

Murray-Kolb et al. [34] IFAZn |

50 | 12.5 | 10 | ||||||||||||

|

Sudfeld et al. [38] MVs (+Zn) |

0.5 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 130 mg | 60 | 8.0 | 5.0 | ||||||

|

Yousafzai et al. [35] Sprinkle MNPs2 |

X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Risk of bias domains | ||||||

| Reference | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | Overall risk of bias |

| Caulfield et al. [37]1 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Christian et al. [33]2 | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Dulal et al. [40]3 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Prado et al. [31]4 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Sudfeld et al. [38]5 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Zhu et al. [39,41]6 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Murray-Kolb et al. [43]7 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

|

Sudfeld et al. [38]8 Child follow-up |

Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Yousafzai et al. [35]9 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Christian et al. [36]2, 7 | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | High |

| Study | Study Design | Cognitive development | Motor development | Behavioral development |

| Caulfield et al. [37] | RCT | ◄► | ◄► | |

| Christian et al. [33] | CRCT | ◄► | ▼ | |

| Christian et al. [36] | CRCT | ◄► | ▼ | |

| Murray-Kolb et al. [43] | CRCT | ◄► | ◄► | |

| Yousafzai et al. [35] | CRCT | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| Prado et al. [31] | CRCT | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| Dulal et al. [40] | RCT | ◄► | ||

| Zhu et al. [39,41] | CRCT | ▲ | ◄► | |

| Sudfeld et al. [38] | RCT | ◄► | ◄► | |

| Sudfeld et al. [38] | RCT | ◄► | ◄► |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).