Cellular prion protein (PrPC) is a host protein anchored to the outer surface of neurons and, to a lesser extent, lymphocytes. The transmissible agent (PrPSc) responsible for scrapie is believed to be a modified form of PrPC. However, the physiological role of PrPC in normal, uninfected animals remains unknown. Here, we describe a novel mouse model of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) observed during the development of prion agent-susceptible transgenic (Tg) mice. These Tg mice selectively express scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah) PrP (OrPrP) in their tissues, as demonstrated by RT-PCR for mRNA, Western blotting, and immunohistochemistry. High levels of OrPrP expression were detected in the heart, moderate levels in skeletal muscle, low levels in the brain, and barely detectable levels in the lung, liver, spleen, kidney, and thymus. Notably, electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis revealed that cardiac muscle contraction was significantly prolonged, with abnormalities in the QRS interval. Additionally, histological examination showed multiple intracytoplasmic vacuolations in the heart muscle. These findings suggest that high expression of OrPrP in the heart may contribute to cardiac abnormalities. Furthermore, an abnormal ECG waveform was observed in these Tg mice following atropine injection. This mouse model may provide a valuable tool for studying experimental DCM.

1. Introduction

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), such as scrapie or bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in animals and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans, are associated with the prion protein (PrP) isoform known as scrapie prion protein (PrP

Sc), a modified form of the normal cellular prion protein (PrP

C) [

1,

2]. PrP

C appears to have physiological roles, as its gene expression has been observed in the brain and other tissues of all mammals. It is believed that PrP

C converts to PrP

Sc during prion infection through a posttranslational mechanism. However, the function of PrP

C in uninfected animals remains unclear. Interestingly, one study reported that overexpression of PrP

C leads to the formation of PrP

Sc-like abnormal lesions [

3]. According to this report, uninoculated older mice expressing high copy numbers of murine PrP developed truncal ataxia and tremors, indicating that the elevated PrP expression is associated with neurological disease. Therefore, if PrP expression levels are high, it is possible that tissue abnormalities and vacuolation of the tissue may occur.

Cardiomyopathy presents with dyspnea, cardiac failure, or sudden death. Although various triggers, such as viral infections and alcohol abuse, have been implicated in the development of cardiomyopathy, multiple etiologies are often involved. Clinical and molecular genetic studies have revealed a wide range of potential genetic causes for this disease; however, its pathogenesis remains poorly understood [

4]. The absence of a suitable animal model has significantly hindered physicians' ability to elucidate the underlying causes and mechanisms of cardiomyopathy and to develop more effective treatments. Therefore, an animal model of cardiomyopathy is invaluable for understanding the pathological processes and for developing novel therapies and pharmacological interventions [

5]. Additionally, the relationship between prion disease and cardiomyopathy remains unclear. One study reported the accumulation of PrP

Sc in skeletal muscle of hamsters orally infected with scrapie [

6]. Cardiomyopathy and neuromuscular abnormalities may simultaneously coexist [

7]. Moreover, neurodegenerative diseases such as Friedreich's ataxia and Parkinson's disease are frequently associated with cardiomyopathy [

8]. Here, we describe a novel mouse model of cardiomyopathy that was observed during the development of a prion agent-sensitive Tg mouse. Notably, these mice were engineered to ubiquitously express scimitar-horned oryx (

Oryx dammah) PrP (OrPrP) in nerve cells, immune cells, and other cell types using the β-actin promoter.

2. Development of Cardiomyopathy in Tg Mice

2.1. Evolutionary Aspect of the PrP Gene

Tg mice were used in this study. According to Prusiner et al., each pathogen from BSE, scrapie, and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) was transmitted to Tg mice expressing the bovine PrP gene, with incubation periods of approximately 200 days [

9]. The Tg mouse study suggests that these three pathogens are identical. Additionally, Collinge et al. reported using Tg mice transfected with the human PrP gene; in these mice, vCJD appeared after about 220 days [

10]. Depending on the prion strain, the incubation period in Tg mice can be either shortened or prolonged. This species barrier phenomenon related to the PrP gene remains poorly understood.

It is known that wild ruminants such as the greater kudu (

Tragelaphus strepsiceros) and scimitar-horned oryx (

Oryx dammah) have shorter incubation periods compared to livestock ruminants such as sheep and cattle, and their disease progression after incubation is rapid [

11,

12]. Species differences in the incubation time of prion diseases have been reported. On farms, animals are typically infected neonatally. Sheep scrapie exhibits an incubation period of 36 to 48 months following experimental infection. Experimentally infected cattle with the BSE agent show an incubation period of 36 to 72 months. The age of disease onset is 30 to 48 months in sheep scrapie and 60 to 80 months in BSE. However, in oryx, disease was observed at approximately 30 months of age, with an incubation period estimated at 21 months [

11,

12]. The age of disease onset in oryx is considerably earlier compared to cattle and sheep. The transmissibility of spongiform encephalopathies and their incubation periods are influenced by differences in the amino acid sequences of the prion protein (PrP). The gene encoding PrP has been identified in many vertebrates, including humans, sheep, cattle, mice, hamsters, oryx, and fish. Among mammals, there is more than 90% amino acid sequence homology [

13,

14,

15,

16]. It is possible that specific critical amino acid sequences in oryx PrP control the incubation period and age of disease onset.

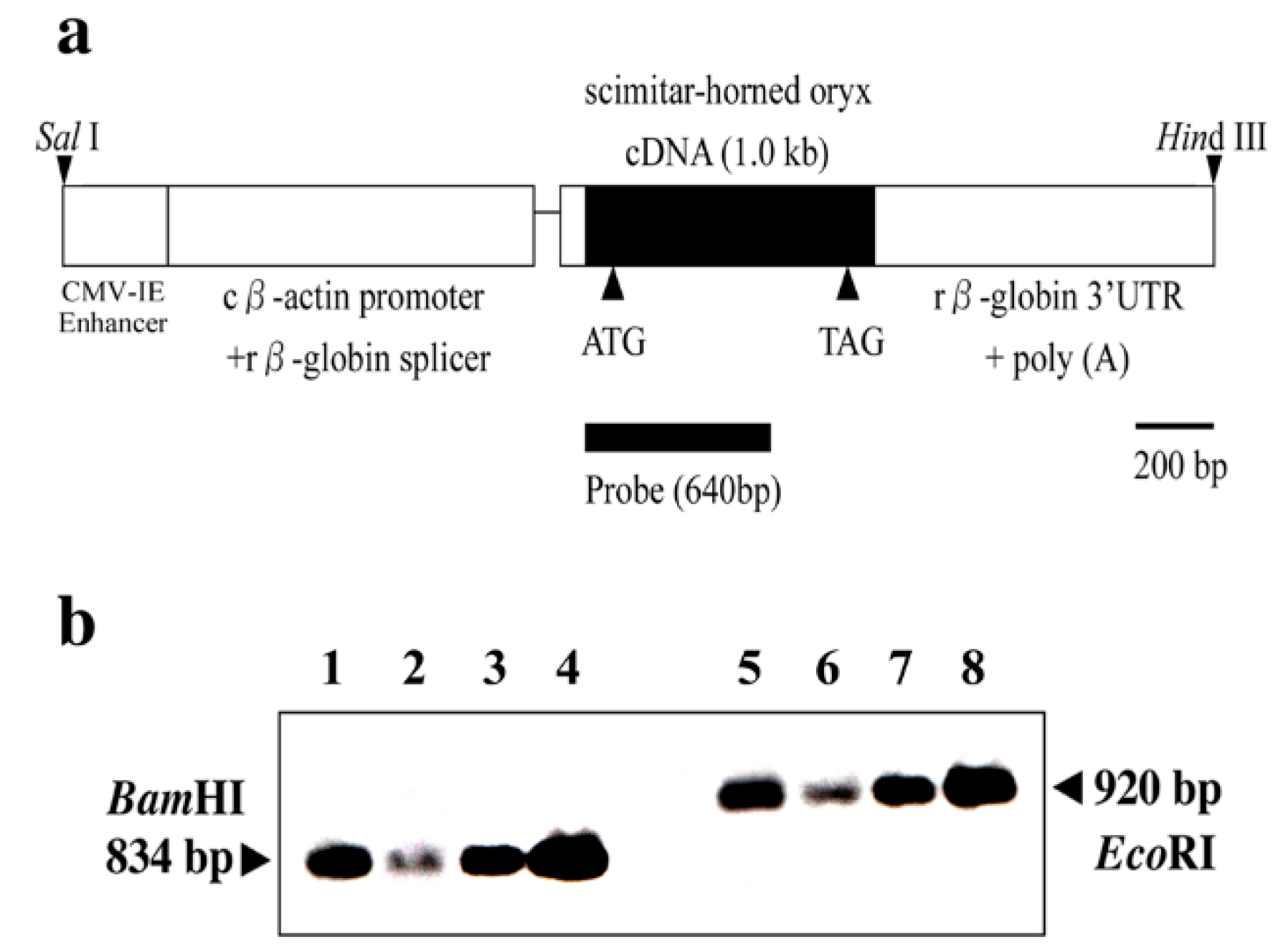

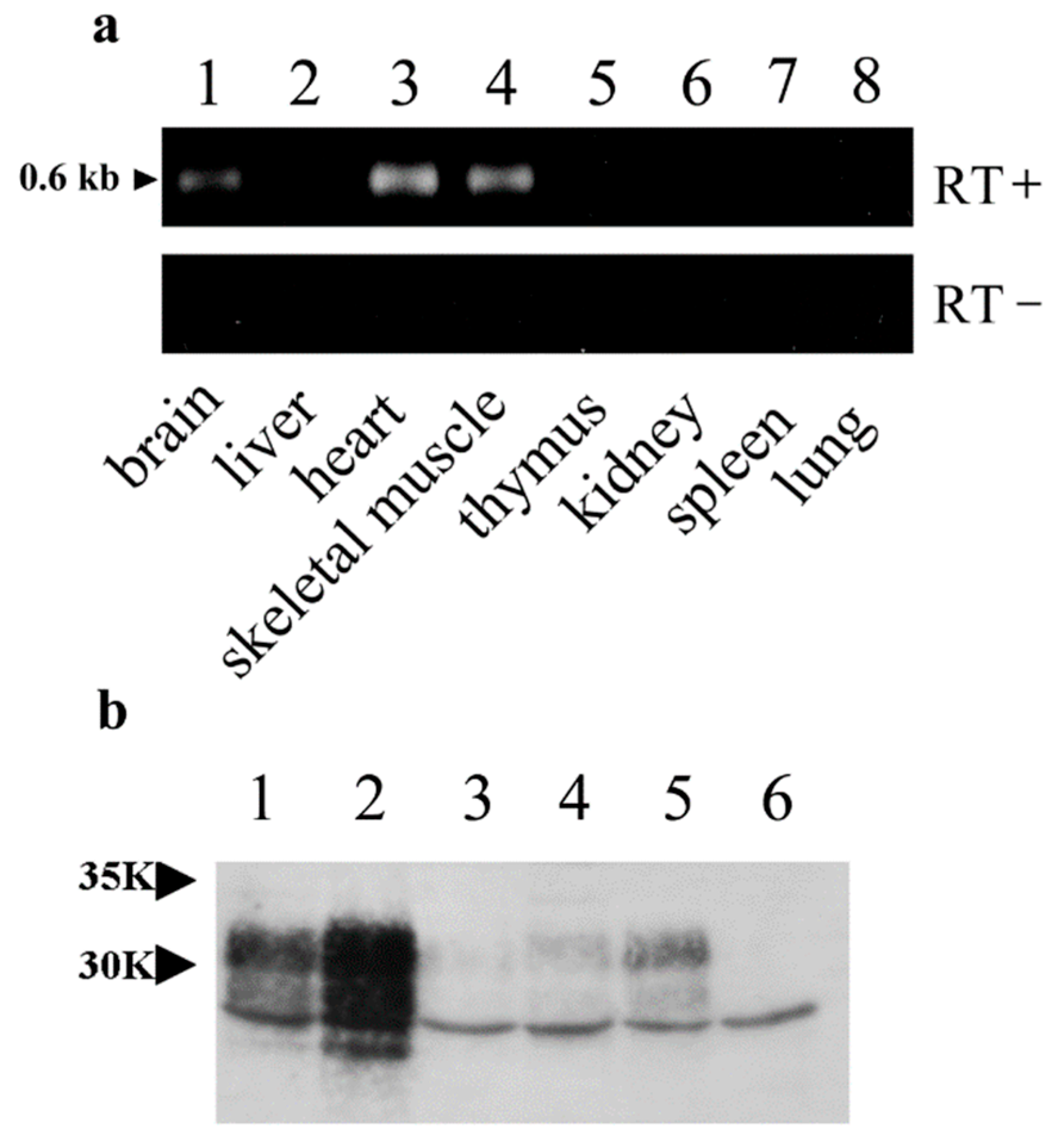

2.2. Effect of PrP Genes in Tg Mice

Transgenic technology is useful for analyzing the normal function of PrP and genetically contrasting susceptibility to various agents. Although the chicken β-actin promoter and CMV enhancer are known to drive widespread gene expression [

17,

18], transgene expression is not always ubiquitous [

18]. According to our results, OrPrP expression was highest in the heart, moderate in the skeletal muscle, and lowest in the brain. These expression patterns suggest that the localization of transgene expression may contribute to the sudden death of mice (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

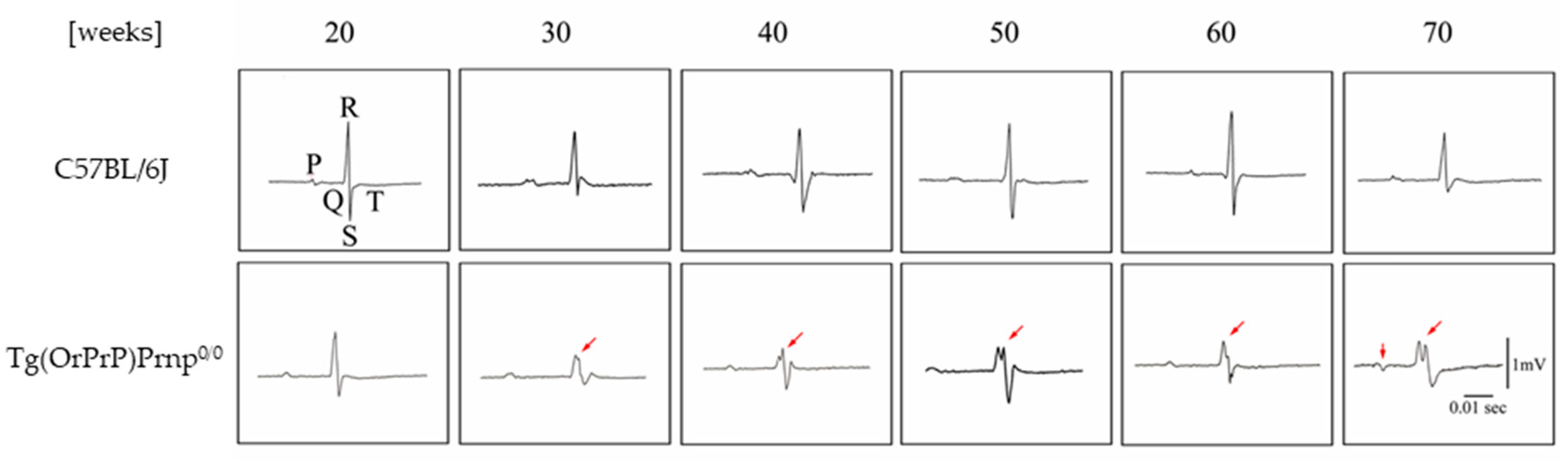

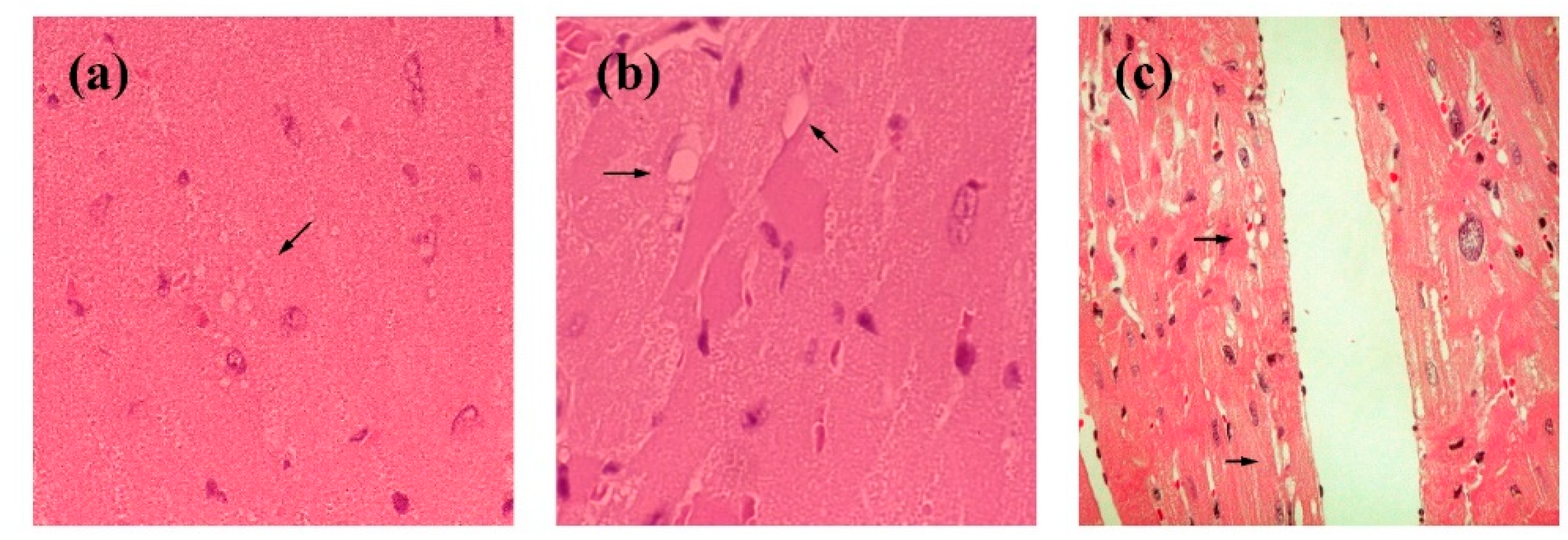

The transgene (OrPrP) was expressed at high levels in the heart and skeletal muscle, likely because the chicken β-actin promoter is highly efficient in mouse myoblasts, as previously reported [

19]. Several studies have suggested that elevated transgene expression in the heart can occur without detectable adverse effects, although minor cardiac pathology may be present [

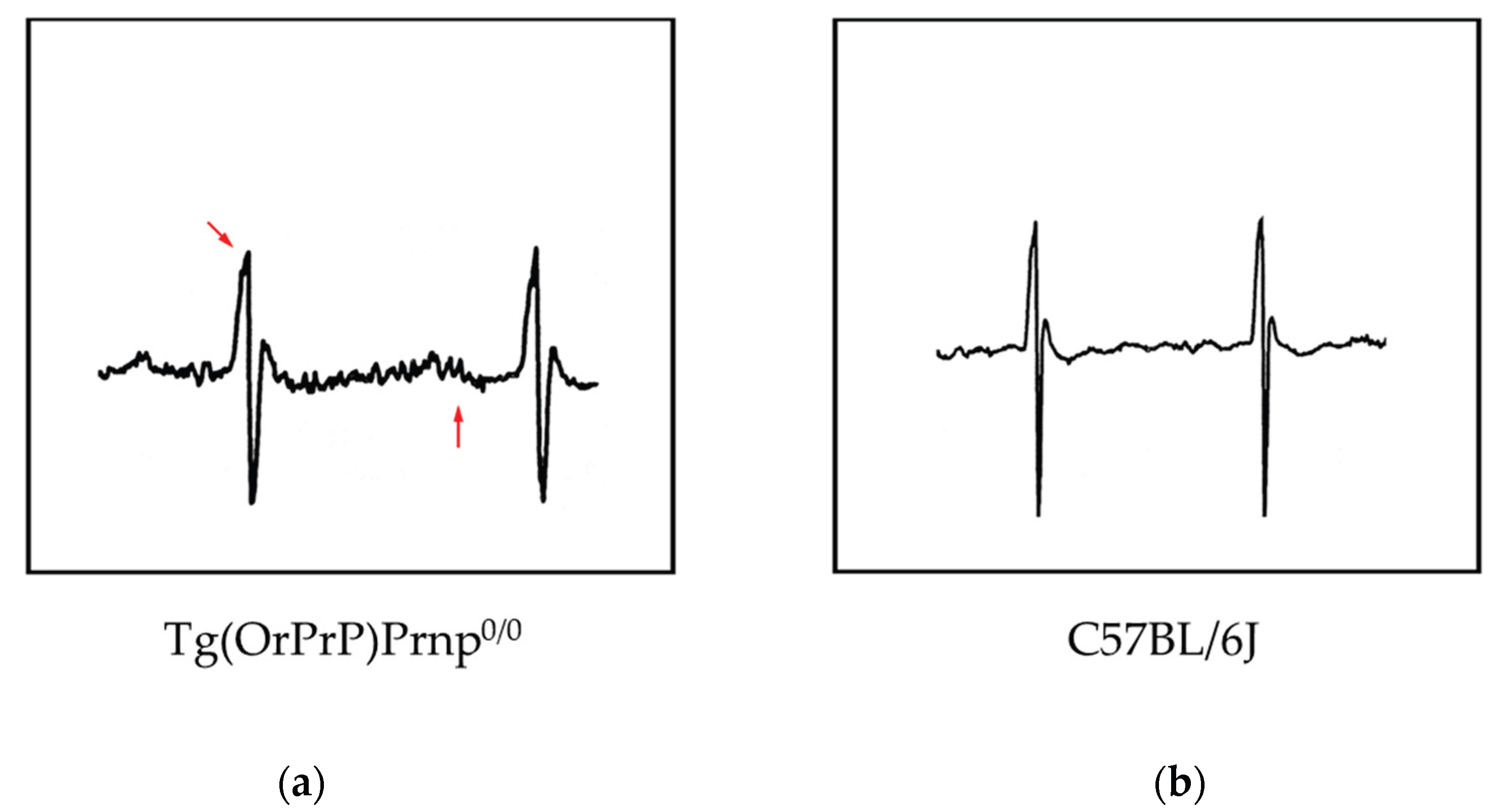

20]. To detect subtle pathological changes, the author analyzed electrocardiograms (ECGs) from Tg(OrPrP)Prnp

0/0 mice aged 20 to 70 weeks. Interestingly, abnormal electrocardiographic patterns were observed in these mice; cardiac muscle contraction was significantly prolonged, accompanied by an abnormal QRS interval. Histological examination revealed multiple intracytoplasmic vacuolations and elongation of muscle fibers in the heart, along with scar formation in muscle tissue. Based on the observed QRS waveform abnormalities, it is inferred that excitability transfer from the atrium to the ventricle was impaired, likely due to injury caused by intracytoplasmic vacuolation. Intracytoplasmic vacuolation of the heart muscle was also detected in both Tg(OrPrP)Prnp

+/+ and Tg(OrPrP)Prnp

0/0 mice (data not shown). Overexpression of OrPrP may induce intracytoplasmic vacuolation in cardiac muscle. Although heart muscle abnormalities were evident in 30 weeks old Tg(OrPrP)Prnp

0/0 mice, other organs—including the brain, lung, liver, spleen, skeletal muscle, thymus, and kidney—showed no abnormalities. Ma et al. demonstrated that wild-type PrP

C exhibits neurotoxicity when accumulated in the cytosol [

21]. Misfolded PrP molecules are retrogradely transported to the cytosol for degradation by the proteasome [

22]. Small amounts of OrPrP may be toxic to cardiac muscle; proteasomal degradation mitigates this toxicity by clearing accumulated OrPrP. However, when proteasomal degradation capacity declines with aging, increased cytosolic PrP accumulation may damage the heart muscle. Aging effects in Tg mice are also documented in this report [

15,

23] (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

These results suggest that intracytoplasmic vacuolation of muscle fibers in aged mice affects the amplitude of the QRS wave in the ECG, likely due to a loss of the electromotive force of the heart muscle. Although abnormal QRS waves can appear in ECGs, none of the Tg(OrPrP)Prnp

0/0 mice exhibited cardiac symptoms such as heart failure. Some previous studies offer alternative interpretations of cardiomyopathy related to these findings, suggesting a genetic disorder involving genes encoding specific proteins. Furthermore, in this study, the hearts of young mice (6 weeks old) showed no gross histological abnormalities, whereas older mice (over 20 weeks old) exhibited abnormalities such as fiber disarray and hyperdynamic contraction. Similar results were observed in our ECG analyses and histopathological examinations. All older mice with histological abnormalities displayed dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) macroscopically. Atropine sulfate inhibits the actions of acetylcholine at postganglionic parasympathetic neuroeffector sites. It is primarily used to increase heart rate in cases of bradycardia. Additionally, atropine serves as an indicative tool for detecting subtle changes in heart muscle function. In Tg(OrPrP)Prnp

0/0 mice, an abnormal ECG waveform was observed following atropine injection. These results suggest that Tg(OrPrP)Prnp

0/0 mice are a valuable model for studying the causes and mechanisms underlying milder forms of cardiomyopathy. Abnormal tissue in the hearts of mice overexpressing PrP has not been previously reported. Additionally, ECG waves were not detected in these PrP-overexpressing mice [

15] (

Figure 5).

2.3. Compatible Transgene Expression in the Heart or Skeletal Muscle

myf5 expression promotes the differentiation of embryonal stem cells into myogenic cells [

24]. Ectopic expression of bovine MyoD in the heart muscle of Tg mice activated certain skeletal muscle-specific sarcomeric genes, resulting in embryonic lethality accompanied by severe cardiac abnormalities. These fetal cardiac muscles exhibited heterogeneity in transgene expression. A similar phenomenon may occur with OrPrP expression in the heart muscle of Tg mice [

15]. Myogenic stem cells can differentiate into either cardiac or skeletal muscle cells. To investigate this process, Tg mice were generated with bovine

myf5 (

bmyf5) transfected into stem cells [

24]. The results demonstrated that ectopic expression of

bmyf5 activated a skeletal muscle gene program that was compatible with normal cardiac function. Both cardiac and skeletal muscle cells developed from the same myogenic stem cells, sharing common structural features. Multiple isoforms of proteins were co-expressed from the same sarcomeric components. Ultimately, these myogenic stem cells differentiate into either skeletal or cardiac muscle cells. These expression patterns are both restricted and distinctive.

Tg mice transfected with the bmyf5 gene were studied in myocardium. Heterozygous mice with bmyf5 survived to adulthood. However, as these heterozygous mice aged, they exhibited severe pathology and abnormalities in their ECG waveforms. Ectopic expression of bmyf5 activates the skeletal muscle program, which is compatible with normal murine cardiac function at younger ages.

Tg overexpression of CaMKIIδc in the heart causes DCM characterized by reduced contractile function, indicating that aberrant expression of signaling kinases can induce cardiac pathology [

25]. Additionally, overexpression of desmocollin-2 (DSC2) in cardiomyocytes leads to severe cardiac dysfunction, including fibrosis, necrosis, and calcification, suggesting that alterations in structural proteins contribute to cardiomyopathy [

26].

Tg overexpression of Gαq in the heart increases susceptibility to contractile dysfunction and cardiomyopathy in mice, likely due to the sensitivity of G-protein signaling to transgene dosage [

27]. Additionally, a truncated troponin T transgene model demonstrates that altered sarcomeric protein function can induce characteristics of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (FHC) [

28]. Furthermore, cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of lysyl oxidase-like protein-1 (LOXL1) promotes cardiac hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis, suggesting another mechanism by which extracellular matrix modifier genes contribute to cardiomyopathy [

29].

Tg and knock-in mouse models targeting desmosomal proteins, such as PKP2 and DSC2, mimic arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. These studies suggest that cell-to-cell adhesion systems are important for maintaining cardiac integrity [

30,

31].

FHC is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins [

32,

33]. A mouse model of FHC was developed by introducing an Arg403, which leads to Gln replacement in the alpha cardiac myosin heavy chain (MHC) gene. This mouse model may help to elucidate the cause of FHC. Histological observations revealed that cardiomyopathy was more pronounced in males than in females and became more apparent with age. Among 10 female alpha MHC sup403/+ mice (including two at 15 weeks old and one at 31 weeks old), no cardiomyopathy was observed. In contrast, all male alpha MHC sup403/+ mice exhibited cardiomyopathy characterized by myocyte disarray. Myocyte hypertrophy, injury, and fibrosis were more frequently observed in 30 weeks old alpha MHC sup403/+ mice compared to 15 weeks old counterparts.

Background genotypes and physiological activity of the phenotype were assessed using a Tg mouse model for FHC. Geister-Lawrance et al. demonstrated that both factors influenced the clinical progression of FHC [

33]. Male mutant mice exhibited histological alterations earlier than female mice. Phenotypic differences between male and female inbred mice are genetically influenced. Based on this, they suggest that other genes may modulate the phenotype of the R403Q myosin mutation. These mice could help identify therapeutic targets for FHC and other cardiomyopathies [

33].

Using the same R403Q myosin mutation mouse model, the physiological aspects of the myocardium were further analyzed [

34]. Alterations in the excitation-contraction system of the myocardium were observed, along with associated changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels. Defective myofilament structure may contribute to the altered intracellular Ca2+ distribution.

2.4. Myocardial Expression of Viral Genes

There is a correlation between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the development of myocardial dysfunction in human patients [

35]. The potential mechanisms reported include the direct effects of HIV proteins (gp120 and Tat) and indirect effects mediated by cytokines, autoimmunity, or antiretroviral drug cytotoxicity [

35]. Tg mice expressing the HIV Tat protein exhibited cardiomyopathy. In mice younger than 3 months, the heart rate was significantly lower in Tg mice (591 ± 47 bpm) compared to control mice (FVB strain) (716 ± 45 bpm). Mild bradycardia and impairments in both systolic and diastolic functions were observed in mice expressing HIV Tat [

35]. These results suggest that HIV proteins may directly contribute to myocardial dysfunction. However, these hypotheses do not exclude other possible factors, such as the effects of cytokines, nutritional status, or co-infection with other pathogens.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has conducted global surveys on viral infections related to cardiovascular disease [

36]. Between 1975 and 1985, Coxsackievirus B (CVB) was identified as the leading cause of cardiovascular diseases, with an incidence rate of 34.6 per 1,000, followed by influenza B (17.4 per 1,000), influenza A (11.7 per 1,000), Coxsackievirus A (9.1 per 1,000), and cytomegalovirus (8.0 per 1,000) [

37]. Acute CVB infection in humans and mice causes rapid and severe myocarditis. While humans may experience chronic infection and potentially full recovery, some develop DCM after recovery [

36].

Infectious viral progeny and viral proteins are usually undetectable in patients with DCM using virus isolation and immunohistochemistry techniques. Conversely, Tg mice expressing Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) genomes exhibit abnormal excitation-contraction coupling, similar to that observed in pressure overload models of cardiomyopathy [

38,

39]. According to Wesley, cardiomyopathy is induced in Tg mice by transfection of CVB3 genomes without production of infectious virions. This disease closely resembles human DCM [

38]. Further studies are needed to identify the specific viral gene regions that affect myocyte function. Viral proteinases may play a significant role in both acute and chronic disease processes.

Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen leader protein (EBNA-LP) is essential for the highly efficient transformation of B lymphocytes by the viral genome. Tg mice carrying an EBNA-LP cDNA construct were generated. In this construct, the widely expressed metallothionein promoter was used [

40]. EBNA-LP was expressed in multiple organs, including the liver, kidney, heart, lung, and spleen. Between the ages of 4 months and over one year, the Tg mice developed symptoms such as congestive heart failure. Fibrillation was not evident in the electrocardiograms; however, a reduction in T-wave amplitude was observed, suggesting abnormalities in ventricular polarization. Subsequently, a high incidence of dilated heart failure was unexpectedly observed [

40]. The disease induced by EBNA-LP expression in Tg mice shares some similarities with human congestive heart failure or DCM. This study suggests that EBNA-LP of Epstein-Barr virus may induce heart failure in mice [

40].

Tg models of cardiomyopathy using viral genomes are relevant to understanding the pathogenesis of human cases. Derived results are valuable to develop the new therapeutic strategies for treatment and prevention of human cardiomyopathy.

2.5. Skeletal Muscle Expression of PrP Genes

Tg mice developed necrotizing myopathy involving skeletal muscle due to overexpression of the PrP gene derived from hamsters or sheep [

41]. Tg mice expressing Prnp exhibited muscle-specific expression with highly restricted regulation by doxycycline (DOX) [

42]. This DOX-regulated expression was strictly limited to skeletal muscles. The Tg mice displayed myopathy characterized by increased variation in myofiber size [

42]. Typical lesions in the myofibers included centrally located nuclei within the cytoplasm. Endomysial fibrosis was observed without intracytoplasmic inclusions or rimmed nuclei. No evidence of neurogenic disorder was detected.

Suardi et al. demonstrated a distinct pattern of prion-induced myopathy in both experimental and natural cases of bovine amyloid spongiform encephalopathy (BASE). Several skeletal muscles, including the

M. longissimus dorsi, M. intercostalis, and

M. gluteus, from BASE-affected cattle contained infectivity. However, the spleen, cervical lymph nodes, and kidneys from these cases did not exhibit infectivity [

43].

Various prion diseases have demonstrated PrP

res deposition in skeletal muscles. These diseases include natural cases of atypical scrapie in sheep, chronic wasting disease in deer, and their experimental infections in mice and hamsters [

44,

45,

46]. These studies agree that PrP

res in murine muscle tissue is associated with terminal nerve endings. However, in Suardi’s report, naturally BASE-affected cattle exhibited PrP

res deposition in the cytoplasm of skeletal muscle cells [

43], which was not related to terminal nerve endings. They conducted bioassays using Tg mice overexpressing bovine PrP (Tgbov XV) and detected infectivity in various muscle samples from cattle with both natural and experimental BASE. Although their report did not indicate involvement of cardiomyocytes, further studies are necessary, particularly during the final stages of experimental BASE in Tg mice (Tgbov XV). Apparently, prion agents are replicating in skeletal muscle myocytes. Prion gene mRNA levels were elevated in the cardiac myocytes of Tg mice, as shown in the following table (

Table 1).

2.6. BSE-Induced Abnormal Heart Rate and Bradycardia

In cattle infected with BSE, abnormalities were observed in electrocardiographic signals using a novel microprocessor-controlled device (NeuroScope, Pontoppidan, Denmark) [

47]. This device provides physiological information regarding the central control of heart rate online and in real time. Increased cardiac vagal tone was assessed using the mean index of parasympathetic activity (CIPA). This value ranged from 60 to 140 in infected cattle, compared to CIPA values in 15 healthy cattle (mean 6.0 ± 3.2, range 2.5–15.2) [

48]. They suggest that this device may offer a practical test to provide useful information for the ante-mortem diagnosis of BSE.

Cows suspected of BSE were evaluated using auscultation with a portable cardiac monitor [

47,

48]. Bradycardia was observed in BSE-suspected cows, which were later pathologically confirmed. Disturbances in heart rhythm were frequently evident in some cases exhibiting clinical signs of BSE [

48,

49]. The most typical finding was a low heart rate (60–80 beats per minute). Tachycardia was observed as a result of stress, fear, or excitation in the animals [

49]. Healthy cows deprived of food also exhibited bradycardia. Administration of pharmacological doses of atropine indicated that the bradycardia associated with BSE was mediated by increased vagal influence. These results suggest that cardioinhibitory reflexes in the caudal brainstem are functionally altered by the disease.

Bradycardia and its reversal by atropine generally indicate a disturbance in the central cholinergic nervous system in BSE [

49]. Similar involvement of this CNS region has been observed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Down’s syndrome, two human conditions that, like BSE, are characterized by the formation of amyloid deposits in the CNS. Increased pupillary sensitivity to tropicamide has also been reported in AD [

50,

51] and forms the basis of a proposed diagnostic test for both clinical and preclinical stages of the disease [

49]. Further clinical observations are needed in human AD, bovine BSE, and cardiomyopathy.

3. Discussion and Future Directions

Neurodegenerative diseases are sometimes associated with cardiomyopathy [

7,

8]. Protein misfolding disorders (PMDs) are a group of diseases characterized by misfolding, aggregation, and accumulation of at least one protein or peptide in tissues [

52]. PMDs include several neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and TSE, as well as systemic disorders like familial amyloid polyneuropathy and type 2 diabetes [

52,

53,

54,

55].

Aggregation of α-synuclein has been linked to neurodegenerative diseases, especially PD [

54], because α-synuclein maintains transmissibility after serial passage [

55]. α-Synuclein is well-studied in Tg mouse models. Aggregation of α-synuclein induced by brain homogenate requires the presence of the human mutant form of α-synuclein in the mouse genome [

55]. At this stage, PD mice exhibit partial neurological disorders like those observed in human patients [

52].

The complicated results from PD, multiple system atrophy (MSA) studies suggest that α-synuclein aggregates are heterogeneous among diseases. They differ from the original diseases in cell types—neuronal inclusion bodies in dementia with Lewy bodies and PD, or glial inclusions in MSA. Additionally, they differ in their potential for further propagation in mouse cell types [

54,

56]. The toxicity of early aggregates has also been demonstrated in PD [

57]. In early-onset parkinsonism, the loss of nigral and locus coeruleus neurons occurs in the absence of Lewy bodies [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. In the early phase, Tg mice exhibited substantial motor deficiencies and loss of dopaminergic neurons. During the same phase, PD mouse models also showed nonfibrillar α-synuclein deposits in various brain regions. If this PD model also exhibits cardiomyopathy, it could open a new field in PD research. Further studies are necessary.

These studies using PMDs genomes will be more promising when employing Tg mouse models to develop new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of cardiomyopathy.

4. Conclusions

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Friedreich's ataxia (FA) and PD, are frequently associated with cardiomyopathy. We describe a novel mouse model for cardiomyopathy, which was developed during the creation of prion agent-sensitive Tg mice. Specifically, these mice were designed to express OrPrP ubiquitously—including in nerve cells, immune cells, and other cell types—using the β-actin promoter. Tg mouse models are valuable resources for developing cardiac pharmaceuticals for both humans and animals. These mice are also useful for safety testing prior to identifying effective treatments for humans with underlying heart diseases. These Tg mice, which exhibit abnormal ECG waves, are still needed for drug screening. Traditional studies on prion diseases have focused on protein misfolding disorders. Future prion research is more likely to concentrate on understanding aggregation-induced toxicity, abnormal protein topology, and altered intracellular trafficking.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., H.E., H.T., S.I. and T.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S., A.S., H.E., H.T., S.I. and T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was submitted to the Institutional Review Board of The University of Tokyo (notification code: 1818T0061; May 15, 2006).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Major thanks are due to Director Prof. Toru Miyazaki (The Institute for AIM Medicine, Shinjuku 162-0054, Tokyo, Japan) for his intensive discussion of Tg mice developments. We would like to express our gratitude to Drs. Yoshitsugu Matsumoto and Keiichi Saeki (Department of Molecular Immunology, School of Agriculture and Life Sciences, the University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan) for many helpful discussions and advice throughout this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Prusiner, S.B.; Scott, M.; Foster, D.; Pan, K.M.; Groth, D.; Mirenda, C.; Torchia, M.; Yang, S.L.; Serban, D.; Carlson, G.A. Transgenetic studies implicate Prusiner interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell 1990, 63, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusiner, S.B. Transgenetic investigations of prion diseases of humans and animals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1993, 339, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Westaway, D.; DeArmond, S.J.; Cayetano-Canlas, J.; Groth, D.; Foster, D.; Yang, S.L.; Torchia, M.; Carlson, G.A.; Prusiner, S.B. Degeneration of skeletal muscle, peripheral nerves, and the central nervous system in transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type prion proteins. Cell 1994, 76, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.P.; Strauss, A.W. Inherited cardiomyopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 913–919. [Google Scholar]

- Toyooka, T.; Nagayama, K.; Suzuki, J; Sugimoto, T. Noninvasive assessment of cardiomyopathy development with simultaneous measurement of topical1H- and 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Circulation 1992, 86, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomzig, A.; Kratzel, C.; Lenz, G.; Kruger, D.; Beekes, M. Widespread PrPSc accumulation in muscle of hamsters orally infected with scrapie. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 530–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Garcia, J.; Goldenthal, M.J.; Filiano, J.J. Cardiomyopathy associated with neurologic disorders and mitochondrial phenotype. J. Child. Neurol. 2002, 17, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunse, M.; Bit-Avragim, N.; Riefflin, A.; Perrot, A.; Schmidt, O.; Kreuz, F.R.; Dietz, R.; Jung, W.I.; Osterziel, K.J. Cardiac energetics correlates to myocardial hypertrophy in Friedreich's ataxia. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 53, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.R.; Will, R.; Nguyen, H.O.; Tremblay, P.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B. Compelling Transgenic evidence for transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions to humans. Pros. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1999, 96, 15137–15142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telling, G.C.; Scott, M.; Hsiao, K.K.; Foster, D.; Yang, S.L.; Torchia, M.; Sidle, M.; Collinge, G.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B. Transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from humans to transgenic mice expressing chimeric human-mouse prion protein. Pros. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1994, 91, 9936–9940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.K.; Cunningham, A.A. Epidemiological observations on spongiform encephalopathies in captive wild animals in the British islets. Vet. Rec. 1994, 135, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A.A.; Kirkwood, J.K.; Dawson, M.; Spencer, Y.I.; Green, R.B.; Wells, G.A.H. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy infectivity in greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesch, B.; Westaway, D.; Prusiner, S.B. Prion protein genes: evolutionary and functional aspects. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1991, 172, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo, P.; Westaway, D. Biology of the prion gene complex. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2001, 79, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itohara, S.; Onodera, T.; Tsubone, H. Prion gene modified mouse which exhibits heart anomalies. US Patent 2003, 6, 657,105. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S.W.; Hara, K.; Kubosaki, A.; Nasu, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Saeki, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Endo, H.; Onodera, T. Comparative analysis of the prion protein open reading frame nucleotide sequences of two wild ruminants, the moufflon and golden takin. Intervirology 2001, 44, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, M.; Shimano, H.; Gotoda, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawamura, M.; Inaba, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Yamada, N. Overexpression of human lipoprotein lipase in transgenic mice. Resistance to diet-induced hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 17924–17929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, H.; Mano, H.; Katsuki, M.; Yazaki, Y.; Hirai, H. Increased tyrosine-phosphorylation of 55 KDa proteins in beta-actin / Tec transgenic mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 206, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, S.; Nagase, T.; Tashiro, F.; Ikuta, K.; Sato, S.; Waga, I.; Kume, K.; Miyazaki, J.; Shimizu, T. Bronchial hyperreactivity, increased endotoxin lethality and melanocytic tumorigenesis in transgenic mice overexpressing platelet-activating factor receptor. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.; Osinska, H.; Hewett, T.E.; Kimball, T.; Klevitsky, R.; Witt, S.; Hall, D. G.; Gulick, J.; Robbins, J. Transgenic over-expression of a motor protein at high levels results in severe cardiac pathology. Transgenic Res. 1999, 8, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wollmann, R.; Lindquist, S. Neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration when PrP accumulates in cytosol. Science 2002, 298, 1781–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Lindquist, S. Wild-type PrP and a mutant associated with prion diseases are subject to retrograde transport and proteasome degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001, 98, 14955–14960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onodera, T. Dual role of cellular prion protein in normal host and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B. Phys. Biol. Sci. 2017, 93, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.G.; Lyons, G.E.; Micales, B.K.; Malhorra, A.; Factor, S.; Leinwand, L.A. Cardiomyopathy in transgenic myf5 mice. Circ. Res. 1996, 1996. 78, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molkentin, J.D.; Robbins, J. With great power comes great responsibility: using mouse genetics to study cardiac hypertrophy and failure. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2009, 2009. 46, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Belke, D.D.; Garnett, L.; Martens, K.; Abdelfatah, N.; Rodriguez, M.; Diao, C.; Chen, Y.X.; Gordon, PM.; Nygren, A.; Gerull, B. Transgenic mice overexpressing desmocollin-2 (DSC2) develop cardiomyopathy associated with myocardial inflammation and fibrotic remodeling. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0174019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Angelo, D.D.; Sakata, Y.; Lorenz, J.N.; Boivin, G.P.; Walsh, R.A.; Liggett, S.B.; Dorn, G.W. Transgenic Gαq overexpression induces cardiac contractile failure in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997, 94, 8121–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardiff, J.C.; Factor, S.M.; Tompkins, B.D.; Hewett, T.E.; Palmer, B.M.; Moore, R.L.; Schwartz, S.; Robbins, J.; Leinwand, LA. A truncated cardiac troponin T molecule in transgenic mice suggests multiple cellular mechanisms for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 1998, 101, 2800–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, H.; Yasukawa, H.; Minami, T.; Sugi, Y.; Oba, T.; Nagata, T.; Kyogoku, S.; Ohshima, H.; Aoki, H.; Imaizumi, T. Cardiomyocyte-specific transgenic expression of lysyl oxidase-like protein-1 induces cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Hypertens Res. 2012, 35, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncayo-Arlandi, J.; Guasch, E.; Sanz-de la Garza, M.; Casado, M.; Garcia, N.A.; Mont, L.; Sitges, M.; Knöll, R.; Buyandelger, B.; Campuzano, O.; Diez-Juan, A.; Brugada, R. Molecular disturbance underlies to arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy induced by transgene content, age and exercise in atruncated PKP2 mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 3676–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerull, B.; Brodehl, A. Genetic Animal Models for Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgakopoulos, D.; Christie, M.E.; Giewat, C.M.; Seidman, J.G.; Kass, D.A. The pathogenesis of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: early and evolving effects from an alpha-cardiac myosin heavy chain missense mutation. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisterfer-Lowrance, A.A.; Christe, M.; Conner, D.A.; Ingwall, J.S.; Seidman, C.E.; Seidman, J.G. A mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Science 1996, 272, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.D.; Perez, N.G.; Seidman, C.E.; Seidman, J.G.; Marban, E. Altered cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in mutant mice with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 1999, 103, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Kan, H.; Lewis, W.; Chen, F.; Sharmann, P.; Finkel, M.S. Dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice expressing HIV Tat. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2009, 9, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friman, G.; Wesslen, L.; Fohlman, J.; Karjalainen, J.; Rolf, C. The epidemiology of infectious myocarditis, lymphocytic myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 1996, 16(Supp. O), 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grist, N.R.; Reid, D. Epidemiology of viral infections of the heart. In Banatvala, J.E. ed. Viral Infections of the Heart; Hodder and Stoughton: London, 1993; pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wessely, R.; Klingel, K.; Santana, L.F.; Dalton, N.; Hongo, M.; Lederer, W.J.; Kandolf, R.; Knowlton, K.U. Transgenic expression of replication-restricted enteroviral genomes in heart muscle induce defective excitation-contraction coupling and dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 1998, 102, 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.M.; Valdivia, H.H.; Cheng, H.; Lederer, M.R.; Santana, L.F.; Cannell, M.B.; McCune, S.A.; Altschuld, R.A.; Lederer, W.J. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science 1997, 276, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huen, D.S.; Fox, A.; Kumar, P.; Searle, P.F. Dilated heart failure in transgenic mice expressing the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-leader protein. J. Gen. Virol. 1993, 74, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, D.; DeArmond, S.J.; Canlas-Cayetano, J.; Groth, D.; Foster, D.; Yang, S.L.; Torchia, M.; Calson, G.A.; Prusiner, S.B. Degeneration of skeletal muscle, peripheral nerves, and central nervous system in transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type prion proteins. Cell 1994, 76, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liang, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Vanegas, D.; Wu, D.; Chakraborty, B.; Hays, A.P.; Chen, K.; Che, S.G.; Booth, S.; Cohen, M.; Gambetti, P.; Kong, Q-Z. Inducible overexpression of wild-type prion protein in the muscles leads to a primary myopathy in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007, 104, 6800-6805.

- Suardi, S.; Vimercati, C.; Casalone, C.; Gelmetti, D.; Corona, C.; Lulini, B.; Mazza, M.; Lombardi, G.; Moda, F.; Ruggerone, M.; Campaganani, I.; Piccoli, E.; Catania, M.; Groschup, M.H.; Balkema-Buschmann, A.; Caramelli, M.; Monaco, S.; Zannuso, G.; Tagliavini, F. Infectivity in skeletal muscle of cattle with atypical bovine spongiform encephalopathy. PloS ONE, 2012, 7, e31449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andréoletti, O.; Orge, L.; Benestad, S.L.; Beringue, V.; Litaise, G.; Simon, S.; Le Dur, A.; Laude, H.; Simmons, H.; Lugan, S.; Corbière, F.; Costes, P.; Morel, N.; Schelcher, F.; Lacroux, C. Atypical/Nos98 scrapie infectivity in sheep peripheral tissues. PLoS Pathog, 2011, 7, e1001285.

- Angers, R.C.; Browning, S.R.; Seward, T.S.; Sigurdson, C.J.; Miller, M.W.; Hoover, E.A.; Telling, G.C. Prions in skeletal muscle of deer with chronic wasting disease. Science 2006, 311, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosque, P.J.; Ryou, C.; Telling, G.; Peretz, D.; Legname, G.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B. Prions in skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002, 99, 3812–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.J.L. Julu, P.; Hansen, S.; Mellor, D.J.; Milne, M.H.; Barrett, D.C. Measurement of cardiac vagal tone in cattle: a possible aid to diagnosis of BSE. Vet. Rec. 1996, 139, 527-528.

- Austin, A.R.; Meek, S.; Webster, S.; Monfrett, C.J.D. Heart rate variability in BSE. Vet. Rec. 1996, 139, 631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Austin, A.R.; Pawson, L.; Meek, S.; Webster, S. Abnormalities of heart rate and rhythm in bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Vet. Rec. 1997, 141, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, W.S.; Goodman, R.M. Hyper-reactivity to atropine in Down’s syndrome. New Engl. J. Med. 1968, 279, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scinto, L.F.; Daffner, K.R.; Dressler, D.; Ransil, B.I.; Rentz, D.; Weintraub, S.; Mesulam, M.; Pqqotter, H. A potential noninvasive neurological test for Alzheimer’s disease. Science 1994, 266, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, T.; Sugiura, K.; Haritani, M.; Suzuki, T.; Imamura, M.; Iwamaru, Y.; Ano, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Sakudo, A. Photocatalytic inactivation of viruses and prions: Multilevel approach with other disinfectants. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 2, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassani, G.; Puggioni, A.; Rossi, A.; Colombo, A.; Onodera, T.; Ferrannini, E.; Toniolo, A. The diabetes pandemic and associated infections: suggestion for clinical microbiology. Rev. Med. Virol. 2019, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Soto, C. Prion-like protein aggregates and type 2 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017, 7, a024315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Morales-Scheihing, D.; Butler, P.C.; Soto, C. Type 2 diabetes as a protein misfolding disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, J.C.; Giles, K.; Oehler, A.; Middleton, L.; Dexter, D.T.; Gentleman, S.M.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B. Transmission of multiple system atrophy prions to transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013, 110, 1955–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusiner, S.B.; Woeman, A.; Mordes, D.A.; Watts, J.C.; Rampersaud, R.; Berry, D.B.; Patel, S.; Oehler, A.; Lowe, J.K.; Kravitz, S.; et al. Evidence for α-synuclein prions causing multiple system atrophy in human with Parkinsonism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2015, 112, E5308–E5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, T.; Ikuno, M.; Hondo, M.; Parajuli, L.K.; Taguchi, K.; Ueda, J.; Sawamura, M.; Okuda, S.; Nakanishi, E.; Hara, J.; Uemura, N.; Hatanaka, Y.; Ayaki, T.; Matsuzawa, S.; Tanaka, M.; El-Agnaf, O.M.A.; Koike, M.; Yanagisawa, M.; Uemura, M.; Yamakado, H.; Takahashi, R. α- Synuclein BAC transgenic exhibit RBD-like behavior and hyposmia: a prodromal Parkinson’s disease model. Brain 2020, 143, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigrudson, C.J.; Nilsson, K.P.; Hornemann, S.; Manco, G.; Fernandez-Borges, N.; Schwarz, P.; Castilla, J.; Wuthrich, K.; Aguzzi, A. A molecular switch controls interspecies prion disease transmission in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzzi, A.; Calella, A.M. Prions: protein aggregation and infectious diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 1105–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, T.; Asakawa, S.; Hattori, N.; Matsumine, H.; Yonemura, Y.; Minoshima, S.; Yokochi, M.; Mizuno, Y.; Shimizu, N. Mutation in the parkin cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 1998, 392, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masliah, E.; Rockenstein, E.; Veinbergs, I.; Mallory, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Takeda, A.; Sagara, Y.; Sisk, A.; Mucke, L. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science 2000, 287, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, F.; Dobson, CM. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2006, 75, 333–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, B.; Constantini, F.; Lacy, E. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press 1986.

- Niwa, H.; Yamamura, K.; Miyazaki, J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 1991, 108, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, J.; Takai, S.; Araki, K.; Tashiro, F.; Tominaga, A.; Takatsu, K.; Yamamura, K. Expression vector system based on the chicken beta-actin promoter directs efficient production of interleukin-5. Gene 1989, 79, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McKinley, M.P.; Hay, B.; Lingappa, V.R.; Lieberburg, I.; Prusiner, S.B. Developmental expression of prion protein gene. Devlop. Biol. 1987, 121, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.E.; Gentleman, S.M.; Ironside, J.W.; McCardle, L.; Lantos, P.L.; Doey, L.; Lowe, J.; Fergusson, J.; Luthert, P.; McQuaid, S.; Allen, I.V. Prion protein immunocytochemistry—UK five center consensus report. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1997, 23, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Keulen, L.J.; Schreuder, B.E.; Meloen, R.H.; Poelen-van den Berg, M.; Mooij-Harkes, G.; Vromans, M.E.; Langeveld, J.P. Immunochemical detection and localization of prion protein in brain tissue of sheep with natural scrapie. Vet. Pathol. 1995, 32, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Tanaka, M.; Iwamaru, Y.; Ushiki, Y.; Kumura, K.M.; Tagawa, Y.; Shinagawa, M.; Yokoyama, T. Effect of tissue deterioration on postmortem BSE diagnosis by immunobiochemical detection of abnormal isoform of prion protein. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2004, 66, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shintaku, T.; Ohba, T.; Niwa, H.; Kushikata, T.; Hirota, K.; Ono, K.; Imaizumi, T.; Kuwasako, K.; Sawamura, D.; Murakami, M. Effects of propofol on electrocardiogram in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 126, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).