Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

17 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection and classification of cases

- 1)

- Sudden Intrauterine Unexpected Death (SIUD) when a fetus, from the 25th gestational week to term, died suddenly and unexpectedly, before complete expulsion or extraction of the fetus from the mother, resulting in a stillbirth for which there was no explanation after review of the maternal clinical history and the performance of a general autopsy of the fetus, including examination of the fetal adnexa, i.e., placental disk, umbilical cord and membranes [7,10,12].

- 2)

- Sudden Neonatal Unexpected Death (SNUD) when a newborn, aged from birth to one month, died suddenly, unexpectedly by history and unexplainably after a thorough case investigation, including performance of a general autopsy, examination of the death scene, and review of the clinical history [7,12,15].

- 3)

- 4)

- Sudden Unexpected Death in the Young (SUDY), when the death occurred in an individual aged 1-35 years, suddenly and unexpectedly in an apparently healthy subject so that such an abrupt outcome could have not been predicted, unexplained after the review of the scene of death and the clinical history, and the performance of a general autopsy.

- 5)

- Sudden Unexpected Death in the Adult (SUDA), when the death occurred in an individual older than 35 years, suddenly and unexpectedly in an apparently healthy subject so that such an abrupt outcome could have not been predicted, unexplained after the review of the scene of death and the clinical history, and the performance of a general autopsy.

2.2. Necropsy investigational protocol

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

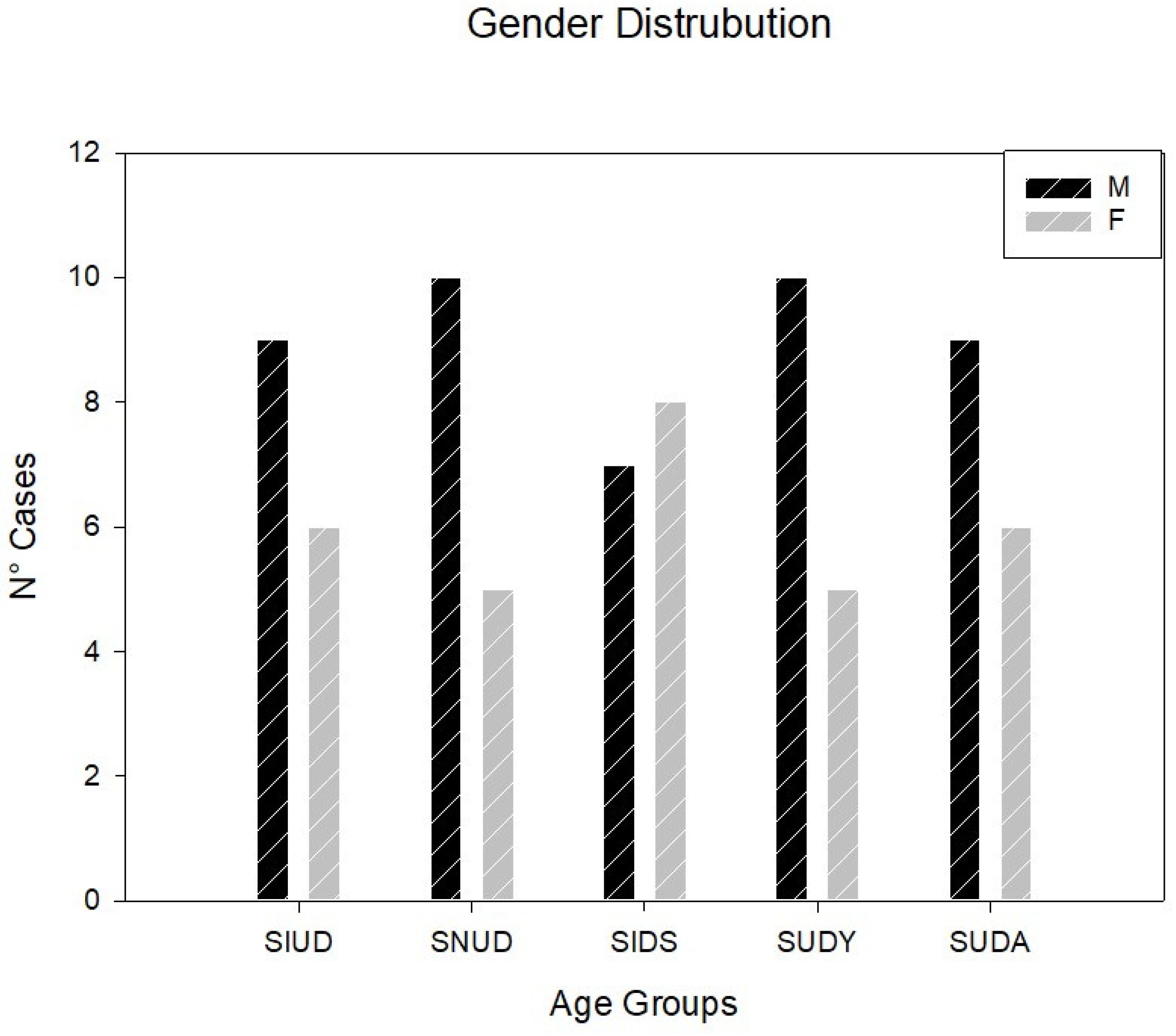

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

- 1)

- 15 victims of sudden intrauterine unexpected death (SIUD) aged 25th gestational week (gw) to birth,

- 2)

- 15 victims of sudden neonatal unexpected death (SNUD) aged from birth to one postnatal month,

- 3)

- 15 victims of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) aged from one postnatal month to one postnatal year,

- 4)

- 15 victims of sudden unexpected death in the young (SUDY) aged 1-35 years (yrs),

- 5)

- 15 victims of sudden unexpected death in the adult (SUDA) older than 35 years, as shown in Table 1.

3.2. Cardiac Conduction System Findings

| SIUD (N=15) | SNUD (N=15) | SIDS (N=15) | SUDY (N=15) | SUDA (N=15) | Total (N=75) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° of cases | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 75 |

| Gender (M/F) | 9/6 | 10/5 | 7/8 | 10/5 | 9/6 | 45/30 |

| Age range; mean ± SD |

27-41 gw; 37.39 ± 3.69 gw |

1 hr-28 dy; 7.08 ± 9.92 dy |

31-225 dy; 105.67 ± 59.84 dy |

14 ms – 33 yr; 22.92 ± 10.33 yr |

36-76 yr; 49.69 ± 11.72 yr |

27 gw-76 yr |

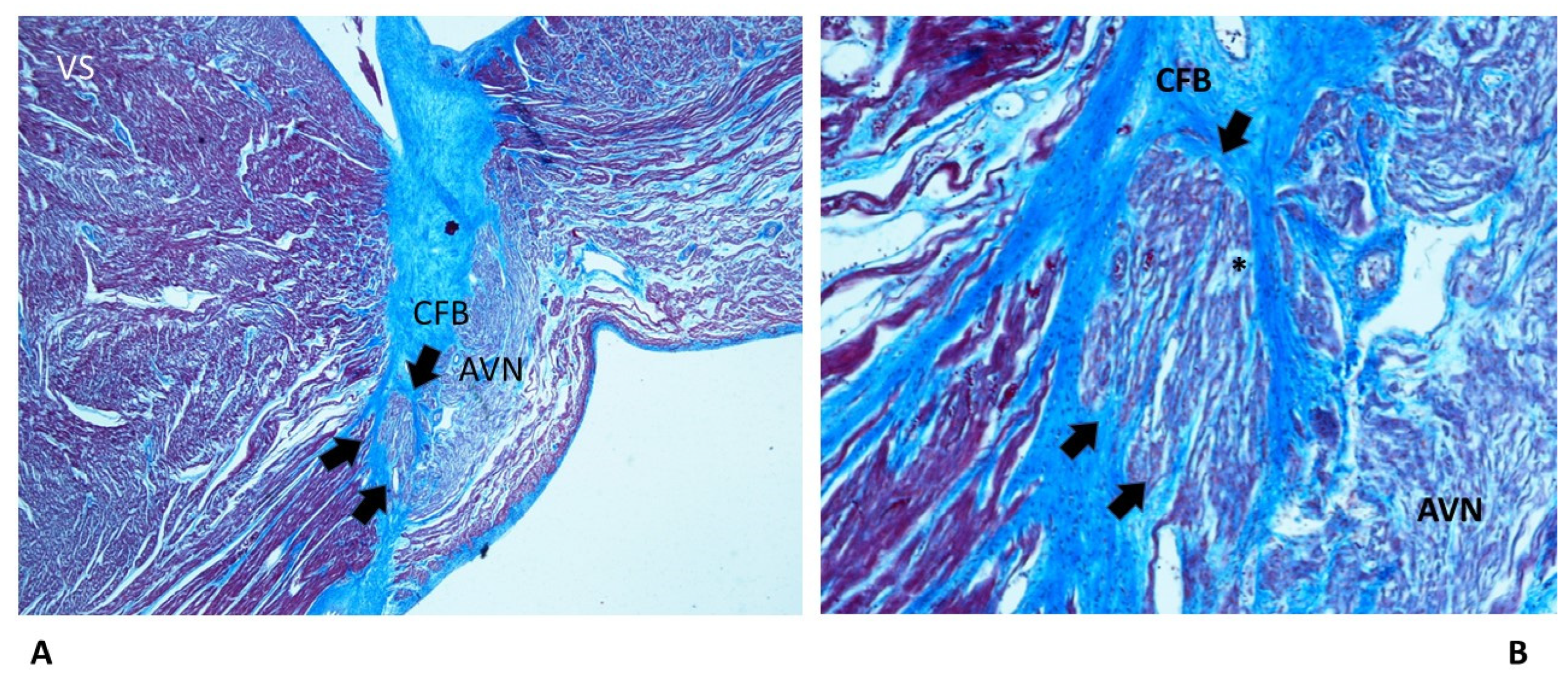

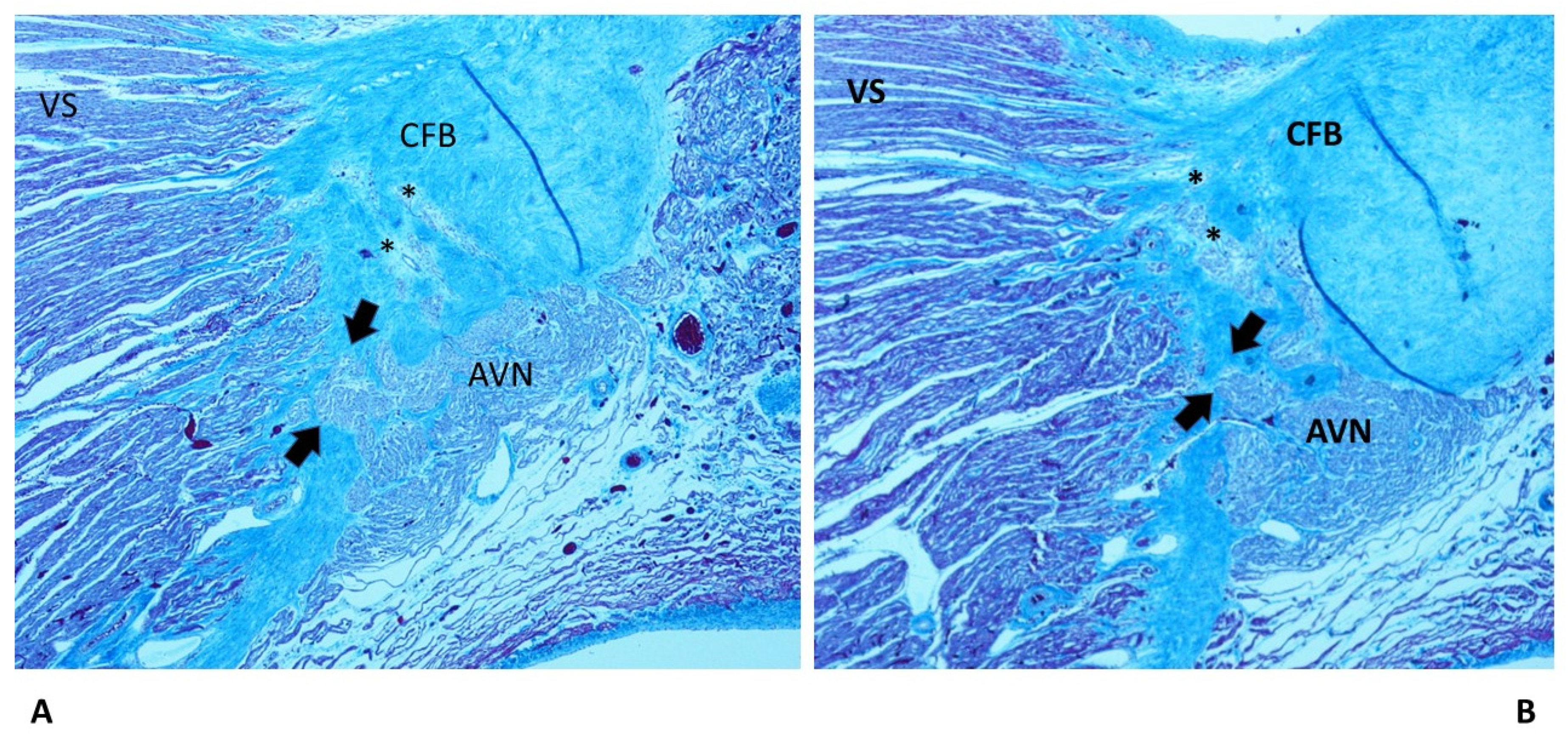

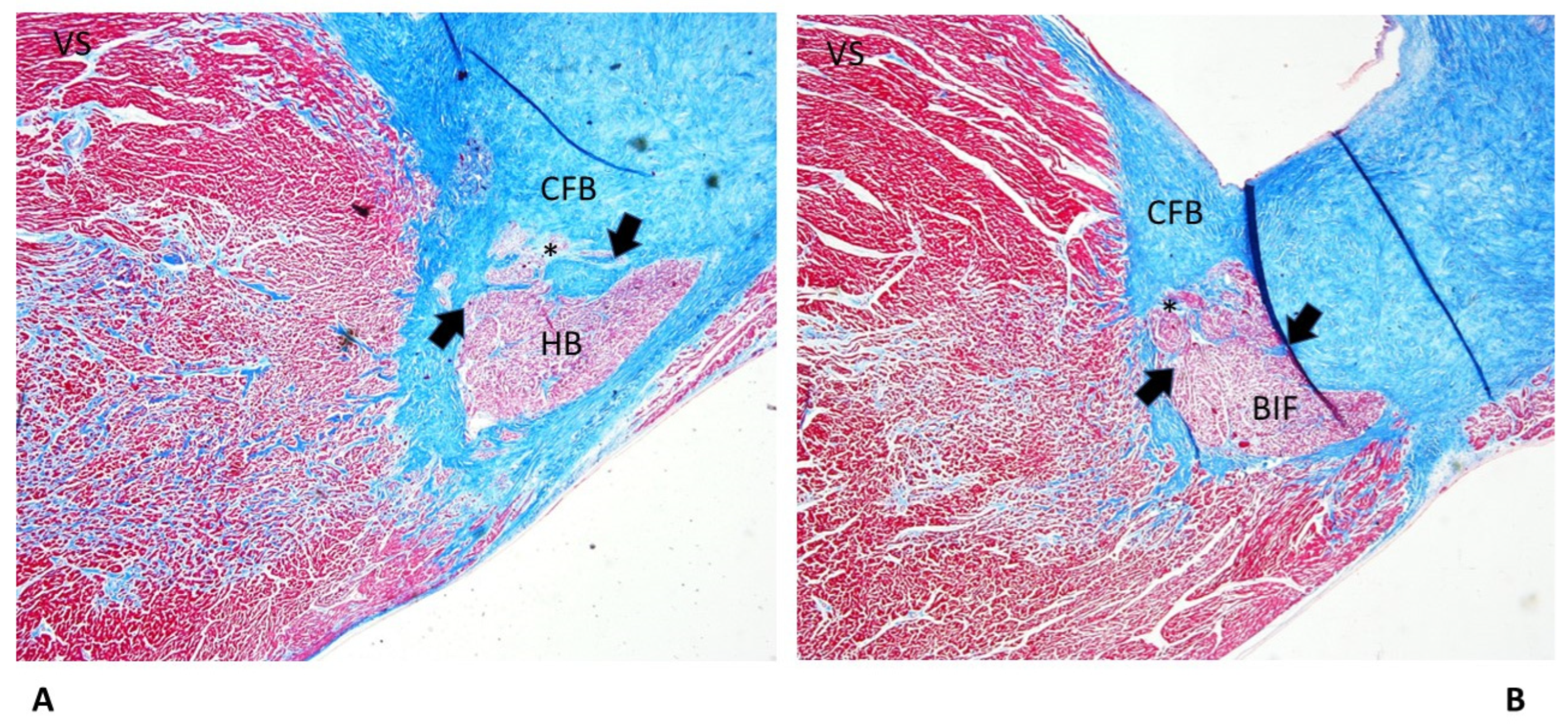

| CFB: Islands of conduction tissue | 10 (66.67%) | 13 (86.67%) | 8 (53.33%) | 6 (40%) | 4 (26.67%) | 41 (54.67%)* |

| Fetal dispersion | 12 (80%) | 12 (80%) | 9 (60%) | 4 (26.67%) | 3 (20%) | 35 (46.67%)* |

| Resorptive degeneration | 10 (66.67%) | 14 (93.33%) | 7 (46.67%) | 2 (13.33%) | 2 (13.33%) | 34 (45.33%)* |

| Mahaim fiber | 5 (33.33%) | 10 (66.67%) | 13 (86.67%) | 3 (20%) | 3 (20%) | 34 (45.33%)* |

| CFB cartilaginous meta-hyperplasia | 5 (33.33%) | 4 (26.67%) | 12 (80%) | 2 (13.33%) | — | 23 (30.67%)* |

| BIF: Septated | 5 (33.33%) | 6 (40%) | 1 (6.67%) | 2 (13.33%) | 4 (26.67%) | 18 (24%) |

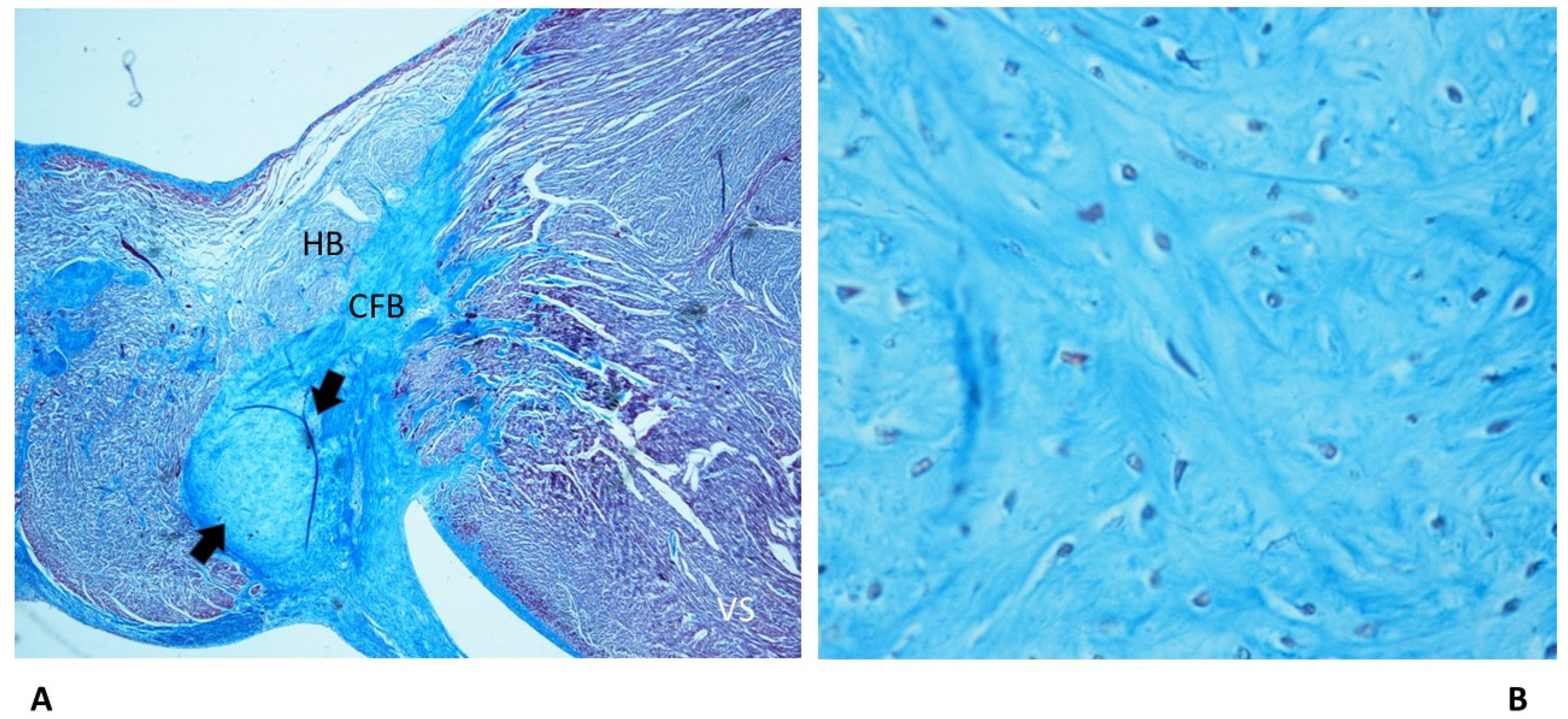

| HB Septated | 1 (6.67%) | 2 (13.33%) | 7 (46.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | 12 (16%)* |

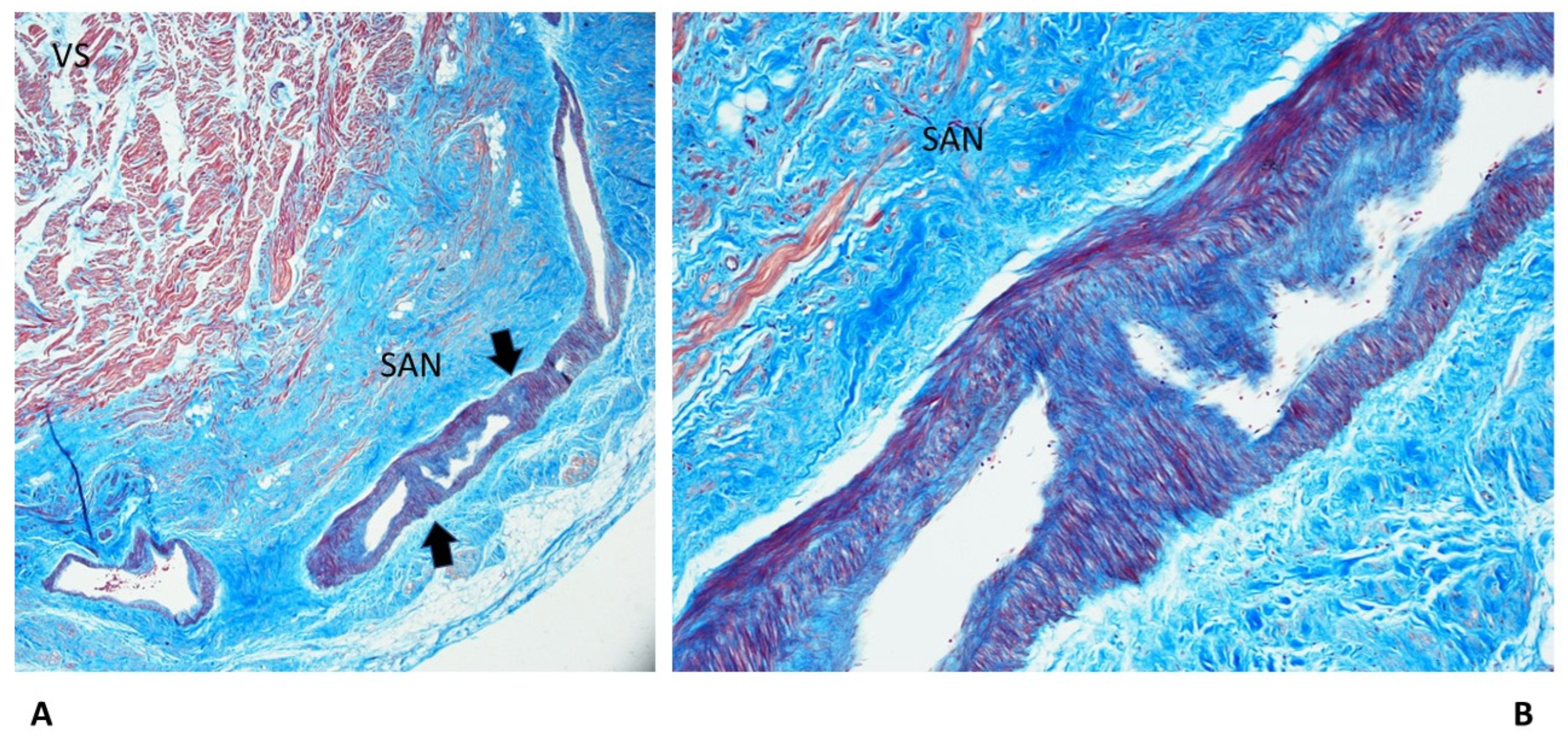

| Fibromuscular thickening SAN artery | — | — | 3 (20%) | 3 (20%) | 5 (33%) | 11 (14.67%)* |

| Fibromuscular thickening AVN artery | — | 1 (6.67%) | 4 (26.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | 4 (26.67%) | 10 (13.33%) |

| AVN duplicity | 1 (6.67%) | 4 (26.67%) | 2 (13.33%) | 1 (6.67%) | — | 8 (10.67%) |

| BIF Intramural | 2 (13.33%) | 3 (20%) | 1 (6.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | 8 (10.67%) |

| AVJ: Hemorrhage and infarct-like lesions | — | 3 (20%) | 1 (6.67%) | 3 (20%) | 2 (13.33%) | 8 (10.67%) |

| AVJ hypoplasia | — | — | — | 1 (6.67%) | 6 (40%) | 7 (9.33%)* |

| RBB: Intramural | 4 (26.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | — | — | 1 (6.67%) | 6 (8%)* |

| CFB hypoplasia | 2 (13.33%) | — | — | 2 (13.33%) | 1 (6.67%) | 5 (6.67%) |

| SAN hypoplasia | — | — | — | 4 (26.67%) | 2 (13.33%) | 4 (5.33%)* |

| AVN Septated | — | 1 (6.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | — | 3 (4%) |

| AVN tongue | — | — | — | 2 (13.33%) | — | 2 (2.67%) |

| LBB: Intramural | 1 (6.67%) | — | 1 (6.67%) | — | — | 2 (2.67%) |

| HB: Intramural | 1 (6.67%) | — | — | 1 (6.67%) | — | 2 (2.67%) |

| HB duplicity | — | — | 1 (6.67%) | 1 (6.67%) | — | 2 (2.67%) |

| SAN: Hemorrhage and infarct-like lesions | — | — | — | — | 1 (6.67%) | 1 (1.3%) |

4. Discussion

4.1. Subjects’ Characteristics

4.2. Anatomo-pathological Findings in the Cardiac Conduction System

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mirzaei, M.; Joodi, G.; Bogle, B.; Chen, S.; Simpson, R.J. Years of Life and Productivity Loss Because of Adult Sudden Unexpected Death in the United States. Med. Care 2019, 57, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviani, G.; Buja, L.M. Anatomopathological Changes of the Cardiac Conduction System in Sudden Cardiac Death, Particularly in Infants: Advances over the Last 25 Years. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2016, 25, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviani, G.; Buja, L.M. Pathology of Unexpected Sudden Cardiac Death: Obstructive Sleep Apnea Is Part of the Challenge. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2020, 47, 107221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krous, H.F.; Beckwith, J.B.; Byard, R.W.; Rognum, T.O.; Bajanowski, T.; Corey, T.; Cutz, E.; Hanzlick, R.; Keens, T.G.; Mitchell, E. a Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Unclassified Sudden Infant Deaths: A Definitional and Diagnostic Approach. Pediatrics 2004, 114, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Linked Birth/Infant Death Records, 2018 Results.

- Willinger, M.; James, L.S.; Catz, C. Defining the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): Deliberations of an Expert Panel Convened by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatr. Pathol. 1991, 11, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviani, G. Defining Sudden Infant Death and Sudden Intrauterine Unexpected Death Syndromes with Regard to Anatomo-Pathological Examination. Front. Pediatr. 2016, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matturri, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Ramos, S.G.; Rossi, L. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): A Study of Cardiac Conduction System. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2000, 9, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, G.; Matturri, L.; Rossi, L.; James, T.N. Crib Death: Further Support for the Concept of Fatal Cardiac Electrical Instability as the Final Common Pathway. Int. J. Cardiol. 2003, 92, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, G.; Matturri, L. Histopathology of the Cardiac Conduction System in Sudden Intrauterine Unexplained Death. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2008, 17, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, G.; Alfonsi, G.; Ramos, S.G.; Buja, L.M. Sudden Unexpected Death Associated with Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy: Study of the Cardiac Conduction System. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matturri, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Lavezzi, A.M. Techniques and Criteria in Pathologic and Forensic-Medical Diagnostics in Sudden Unexpected Infant and Perinatal Death. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 124, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matturri, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Lavezzi, A.M. Guidelines for Neuropathologic Diagnostics of Perinatal Unexpected Loss and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS): A Technical Protocol. Virchows Arch. 2008, 452, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constitution of the Italian Republic Italian Law N° 31. Regulations for Diagnostic Post-Mortem Investigation in Victims of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and Unexpected Fetal Death. Off. Gaz. Ital. Republic, Gen. Ser. 2006, 34:4.

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Mauri, M.; Matturri, L. Alterations of Biological Features of the Cerebellum in Sudden Perinatal and Infant Death. Curr Mol Med 2006, 6, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviani, G. Crib Death - Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Sudden Infant and Perinatal Unexplained Death: The Pathologist’s Viewpoint; 2nd Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-319-08346-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani, G.; Matturri, L.; Bruni, B.; Lavezzi, A.M. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome “Gray Zone” Disclosed Only by a Study of the Brain Stem on Serial Sections. J. Perinat. Med. 2005, 33, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Matturri, L. Developmental Alterations of the Auditory Brainstem Centers--Pathogenetic Implications in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 357, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, P.; Weisæth, L.; Heir, T. Bereavement and Mental Health after Sudden and Violent Losses: A Review. Psychiatry 2012, 75, 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buja, L.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Mitchell, R.N. Pathobiology of Cardiovascular Diseases: An Update. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2019, 42, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e139–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis, A.; Papatheodorou, E.; Ritsatos, K.; Protonotarios, N.; Rentoumi, V.; Gatzoulis, K.; Antoniades, L.; Agapitos, E.; Koutsaftis, P.; Spiliopoulou, C.; et al. Sudden Unexplained Death in the Young: Epidemiology, Aetiology and Value of the Clinically Guided Genetic Screening. Europace 2018, 20, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flenady, V.; Koopmans, L.; Middleton, P.; Frøen, J.F.; Smith, G.C.; Gibbons, K.; Coory, M.; Gordon, A.; Ellwood, D.; McIntyre, H.D.; et al. Major Risk Factors for Stillbirth in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet (London, England) 2011, 377, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matturri, L.; Lavezzi, A.M.; Minoli, I.; Ottaviani, G.; Rubino, B.; Cappellini, A.; Rossi, L. Association between Pulmonary Hypoplasia and Hypoplasia of Arcuate Nucleus in Stillbirth. J. Perinatol. 2003, 23, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matturri, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Lavezzi, A.M.; Rossi, L. Early Atherosclerotic Lesions of the Cardiac Conduction System Arteries in Infants. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2004, 13, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matturri, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Alfonsi, G.; Crippa, M.; Rossi, L.; Lavezzi, A.M. Study of the Brainstem, Particularly the Arcuate Nucleus, in Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and Sudden Intrauterine Unexplained Death (SIUD). Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2004, 25, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Ballabio, G.; Rossi, L.; Matturri, L. Preliminary Study on the Cytoarchitecture of the Human Parabrachial/Kölliker-Fuse Complex, with Reference to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Sudden Intrauterine Unexplained Death. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2004, 7, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Rossi, L.; Matturri, L. Hypoplasia of the Parabrachial/Kölliker-Fuse Complex in Perinatal Death. Biol. Neonate 2004, 86, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Rossi, L.; Matturri, L. Cytoarchitectural Organization of the Parabrachial/Kölliker-Fuse Complex in Man. Brain Dev. 2004, 26, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morpurgo, C. V; Lavezzi, A.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Rossi, L. Bulbo-Spinal Pathology and Sudden Respiratory Infant Death Syndrome. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2004, 21, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Mingrone, R.; Matturri, L. Analysis of the Human Locus Coeruleus in Perinatal and Infant Sudden Unexplained Deaths. Possible Role of the Cigarette Smoking in the Development of This Nucleus. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2005, 154, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavezzi, A.M.; Ottaviani, G.; Matturri, L. Adverse Effects of Prenatal Tobacco Smoke Exposure on Biological Parameters of the Developing Brainstem. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005, 20, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matturri, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Lavezzi, A.M. Maternal Smoking and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: Epidemiological Study Related to Pathology. Virchows Arch. 2006, 449, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamayasu, H.; Miyao, M.; Kawai, C.; Osamura, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Minami, H.; Abiru, H.; Tamaki, K.; Kotani, H. A Proof-of-Concept Study to Construct Bayesian Network Decision Models for Supporting the Categorization of Sudden Unexpected Infant Death. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polavarapu, M.; Klonoff-Cohen, H.; Joshi, D.; Kumar, P.; An, R.; Rosenblatt, K. Development of a Risk Score to Predict Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado, D.; Basso, C.; Schiavon, M.; Thiene, G. Screening for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Young Athletes. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiene, G.; Carturan, E.; Corrado, D.; Basso, C. Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death in the Young and in Athletes: Dream or Reality? Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2010, 19, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, T.N. Sudden Death in Babies: New Observations in the Heart. Am. J. Cardiol. 1968, 22, 479–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matturri, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Lavezzi, A.M.; Turconi, P.; Cazzullo, A.; Rossi, L. Expression of Apoptosis and Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) in the Cardiac Conduction System of Crib Death (SIDS). Adv. Clin. Path. 2001, 5, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- James, T.N. Normal and Abnormal Consequences of Apoptosis in the Human Heart. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1998, 60, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, G.; Matturri, L.; Rossi, L.; Jones, D. Sudden Death Due to Lymphomatous Infiltration of the Cardiac Conduction System. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2003, 12, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, G.; Rossi, L.; Matturri, L. Histopathology of the Cardiac Conduction System in a Case of Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2002, 22, 3029–3032. [Google Scholar]

- Matturri, L.; Ottaviani, G.; Rossi, L. Cardiac Massage in Infants. Intensive Care Med. 2003, 29, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Matturri, L. His Bundle Haemorrhage and External Cardiac Massage: Histopathological Findings. Br. Heart J. 1988, 59, 586–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).