Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

- Identification of exploration objects: Selection of elementary mathematical functions suitable for rotation around coordinate axes.

- Analytical volume computation: Manual calculation of solid volumes using integral calculus, specifically the disk and shell methods.

- GeoGebra-based visualization: Construction of dynamic 2D and 3D models of the curves and their resulting solids of revolution within GeoGebra’s environment.

- Documentation and reflective comparison: Systematic recording and juxtaposition of analytical results against numerical outputs and visual representations generated by GeoGebra.

- Data analysis and triangulation: Critical examination of procedural fidelity, numerical consistency, and conceptual coherence across sources.

- To ensure validity and reliability, the study employs data triangulation through multiple sources: (a) theoretical foundations from scholarly literature, (b) manual analytical computations, and (c) GeoGebra-generated numerical and visual outputs. This triangulation strengthens the internal consistency of findings and supports robust interpretation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results

- Disk method:

3.2. Discussion

| Case | Curve Type | Function | Interval | Shell Method Axis | Disk Method Axis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parabolic | y=x2 | [0,2] | y-axis | x-axis |

| 2 | Linear | y=2x+1 | [0, 3] | y-axis | x-axis |

| 3 | Trigonometric | y=sinx | [0,π] | y-axis | x-axis |

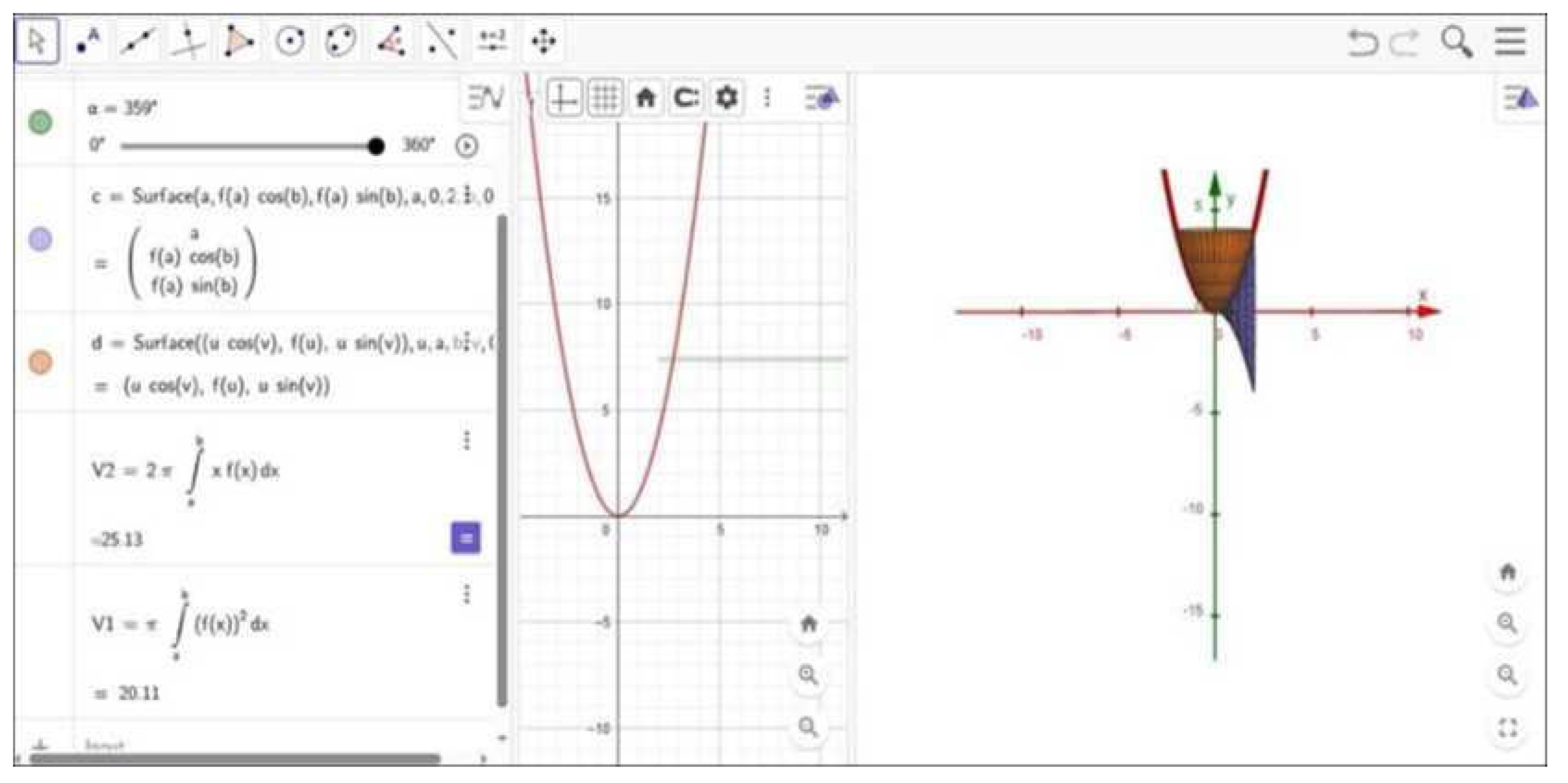

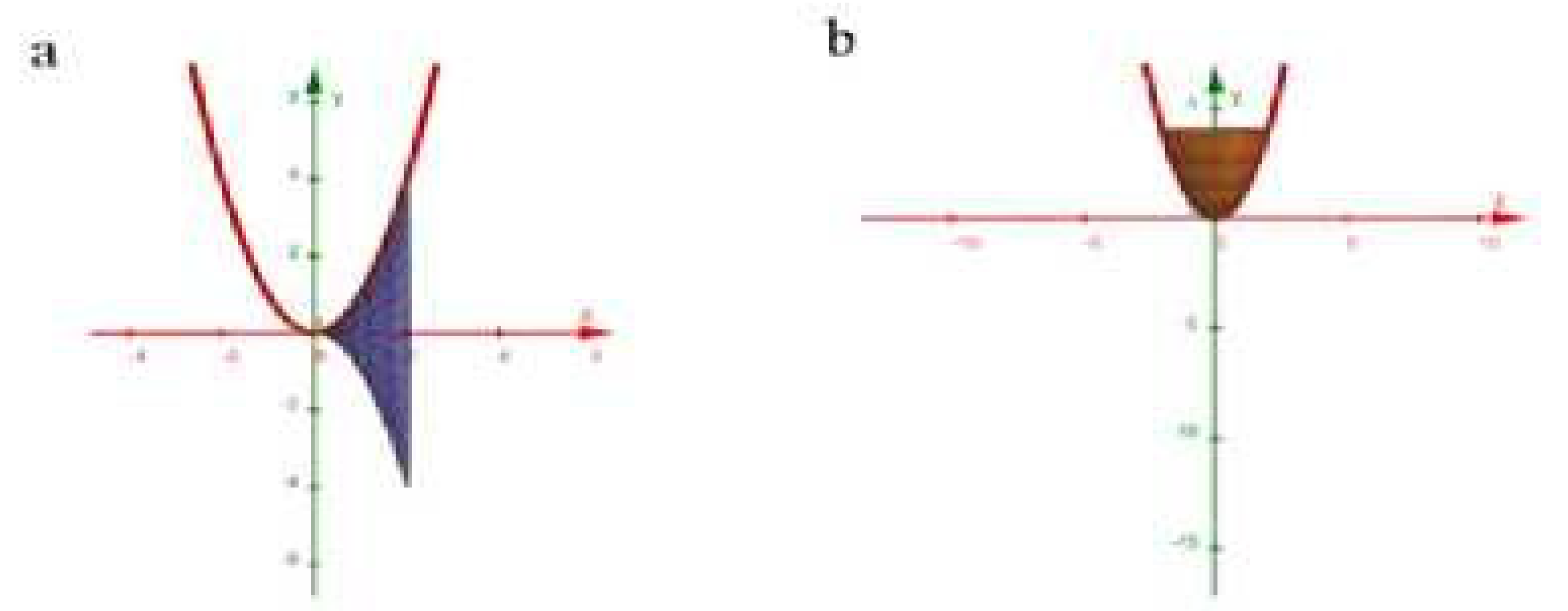

- Figure 2: Solid of revolution from rotating over about the x-axis (disk method) and y-axis (shell method). The resulting paraboloid and hollow cylindrical shell are clearly rendered, allowing inspection of cross-sectional geometry.

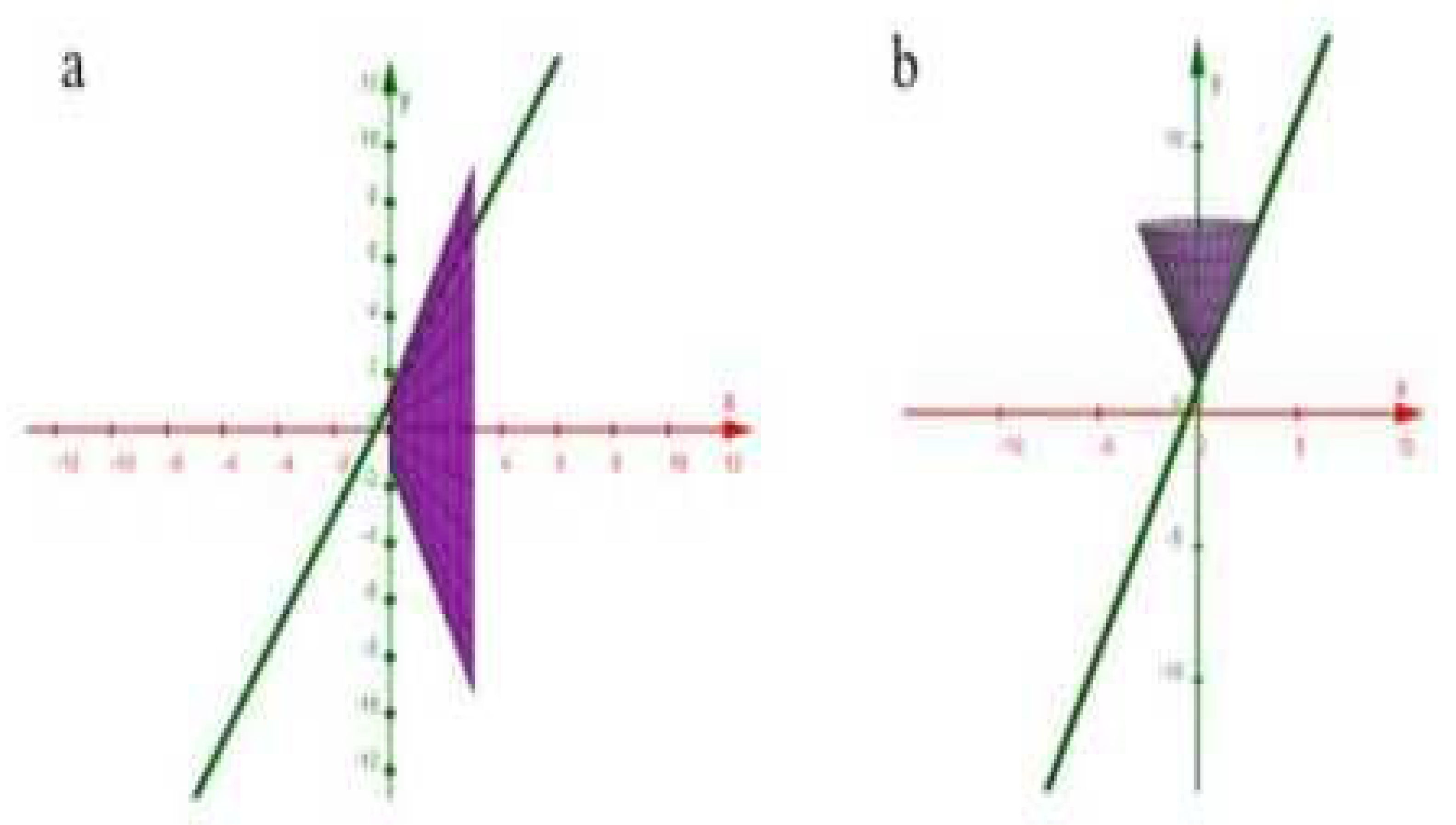

- Figure 3: Solid generated by rotating the linear function over . Rotation about the x-axis yields a conical frustum; rotation about the y-axis produces a tapered cylindrical shell.

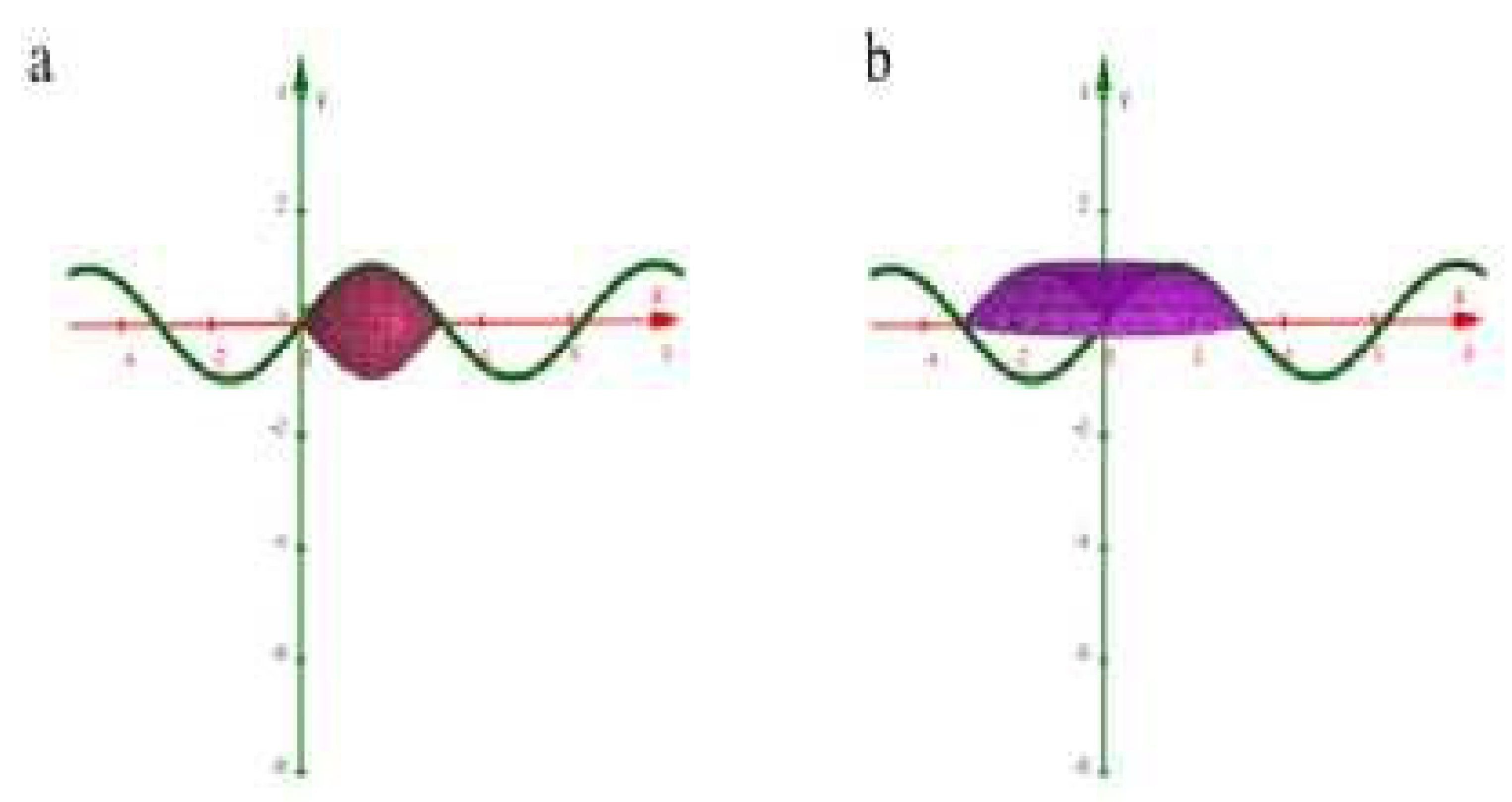

- Figure 4: Rotation of over produces a smooth, symmetric solid resembling a "bumpy barrel" when revolved about the x-axis, and a more complex toroidal-like shape about the y-axis.

- In all cases, GeoGebra’s 3D Graphics and CAS (Computer Algebra System) views were used to:

- Construct the curve and its solid of revolution,

- Compute numerical volume via built-in integral commands,

- Export high-resolution images and interactive .ggb files for documentation.

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendations

- Extend the application of GeoGebra-assisted integral visualization to more complex surfaces of revolution and multivariable calculus topics.

- Investigate the pedagogical impact of GeoGebra-based learning on students’ higher-order mathematical reasoning and spatial visualization skills.

- Integrate GeoGebra with other digital tools or learning management systems to promote adaptive and interactive calculus learning environments.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| CAS | Computer Algebra System |

| PBL | Problem-Based Learning |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| TTW | Think-Talk-Write |

| TPACK | Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge |

| SPLTV | Sistem Persamaan Linear Tiga Variabel (Indonesian: System of Three-Variable Linear Equations) |

| SPTLDV | Sistem Persamaan Linear Dua Variabel (Indonesian: System of Two-Variable Linear Equations) |

| SAMR | Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition (a technology integration model) |

| GeoGebra | Not an acronym; name of dynamic mathematics software |

References

- Hrynevych, L., Morze, N., Vember, V., & Boiko, M. (2021). Use of digital tools as a component of STEM education ecosystem. Educational Technology Quarterly, 2021(2), 118–139. [CrossRef]

- Kukharchuk, R. P., Vakaliuk, T. A., Zaika, O. V., Riabko, A. V., & Medvediev, M. G. (2022). Implementation of STEM learning technology in the process of calibrating an NTC thermistor and developing an electronic thermometer based on it. In S. Papadakis (Ed.), Joint Proceedings of the 10th Illia O. Teplytskyi Workshop on Computer Simulation in Education and Workshop on Cloud-based Smart Technologies for Open Education (CoSinE & CSTOE 2022) (Vol. 3358, pp. 39–52). CEUR-WS.org. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3358/paper25.pdf.

- Pylypenko, O. S., & Kramarenko, T. H. (2024). Structural and functional model of formation of STEM-competencies of students of professional higher education institutions in mathematics teaching. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2871(1), 012004. [CrossRef]

- Mazorchuk, M. S., Vakulenko, T. S., Bychko, A. O., Kuzminska, O. H., & Prokhorov, O. V. (2021). Cloud technologies and learning analytics: Web application for PISA results analysis and visualization. CTE Workshop Proceedings, 8, 484–494. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2015). Incheon Declaration: Education 2030: Towards inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning for all. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233813.

- Bilousova, L. I., Gryzun, L. E., Lytvynova, S. H., & Pikalova, V. V. (2022). Modelling in GeoGebra in the context of holistic approach realization in mathematical training of pre-service specialists. In S. Semerikov, V. Osadchyi, & O. Kuzminska (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology – Volume 1: AET (pp. 499–510). SciTePress. [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, A., & Chen, H.-L. (2023). GeoGebra in mathematics education: A systematic review of journal articles published from 2010 to 2020. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(10), 5682–5697. [CrossRef]

- Awaji, B. M., Khalil, I., & Al-Zahrani, A. (2025). A bibliometrics study of two decades of GeoGebra research in mathematics education. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 15(1), 130–150. [CrossRef]

- Lachner, A., Fabian, A., Franke, U., Preifi, J., Jacob, L., Fuhrer, C., Kuchler, U., Paravicini, W., Randler, C., & Thomas, P. (2021). Fostering pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): A quasi-experimental field study. Computers & Education, 174, 104304. [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J., Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Baran, E. (2020). Enhancing pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): A mixed-method study. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(1), 319–350. [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko, O. (2020). Development of critical thinking as a means of forming STEM competencies. Educational Dimension, 3, 317–331. [CrossRef]

- Shapovalov, Y. B., Shapovalov, V. B., Andruszkiewicz, F., & Volkova, N. P. (2020). Analyzing of main trends of STEM education in Ukraine using stemua.science statistics. CTE Workshop Proceedings, 7, 448–46. [CrossRef]

- Shapovalov, Y. B., Bilyk, Z. I., Usenko, S. A., Shapovalov, V. B., Postova, K. H., Zhadan, S. O., & Antonenko, P. D. (2022). Using personal smart tools in STEM education. In S. Semerikov, V. Osadchyi, & O. Kuzminska (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology – Volume 2: AET (pp. 192–207). SciTePress. [CrossRef]

- Valko, N. V., & Kushnir, N. O., & Osadchyi, V. V. (2020). Cloud technologies for STEM education. CTE Workshop Proceedings, 7, 435–447. [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, O. O., Martyniuk, O. S., Pankevych, S., & Muzyka, I. (2021). Educational direction of STEM in the system of realization of blended teaching of physics. Educational Technology Quarterly, 2021(4), 347–359. [CrossRef]

- Lukychova, N. S., Osypova, N. V., & Yuzbasheva, G. S. (2022). ICT and current trends as a path to STEM education: Implementation and prospects. CTE Workshop Proceedings, 9, 39–55. [CrossRef]

- Slipukhina, I. A., Polishchuk, A. P., Mieniailov, S. M., Opolonets, O. P., & Soloviov, T. V. (2022). Methodology of M. Montessori as the basis of early formation of STEM skills of pupils. In S. Semerikov, V. Osadchyi, & O. Kuzminska (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology – Volume 1: AET (pp. 211–220). SciTePress. [CrossRef]

- Mintii, M. M. (2023). STEM education and personnel training: Systematic review. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2611(1), 012025. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, J., & Granberg, C. (2019). Dynamic software, task solving with or without guidelines, and learning outcomes. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 24(3), 419–436. [CrossRef]

- Dahal, N., Pant, B. P., Shrestha, I. M., & Manandhar, N. K. (2022). Use of GeoGebra in teaching and learning geometric transformation in school mathematics. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 16(8), 65–78. [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, A. T. (2019). The creativity of pre-service mathematics teachers in designing GeoGebra-assisted mathematical task. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1280(4), 042026. [CrossRef]

- Kramarenko, T. H., Pylypenko, O. S., & Muzyka, I. O. (2020). Application of GeoGebra in stereometry teaching. CTE Workshop Proceedings, 7, 705–718. [CrossRef]

- Drushlyak, M. G., Semenikhina, O. V., Proshkin, V. V., Kharchenko, S. Y., & Lukashova, T. D. (2021). Methodology of formation of modeling skills based on a constructive approach (on the example of GeoGebra). CTE Workshop Proceedings, 8, 458–472. [CrossRef]

- Kramarenko, T. H., Pylypenko, O. S., & Moiseienko, M. V. (2023). Enhancing mathematics education with GeoGebra and augmented reality. In S. O. Semerikov & A. M. Striuk (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Augmented Reality in Education (AREdu 2023) (Vol. 3844, pp. 117–126). CEUR-WS.org. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3844/paper03.pdf.

- Havelkova, V. (2013). GeoGebra in teaching linear algebra. In Proceedings of the European Conference on e-Learning (ECEL) (pp. 581–589).

- Aliu, E. R., Jusufi Zenku, T., Iseni, E., & Rexhepi, S. (2025). The advantage of using GeoGebra in the understanding of vectors and comparison with the classical method. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education, 20(1), em0824. [CrossRef]

- Zengin, Y. (2019). Development of mathematical connection skills in a dynamic learning environment. Education and Information Technologies, 24(4), 2175–2194. [CrossRef]

- Zulfiani, Z., Suwarna, I. P., El Islami, R. A. Z., & Sari, I. J. (2025). Trends in SAMR research in teaching and learning from 2019 to 2024: A systematic review. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 12(4), 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Zengin, Y. (2017). The effects of GeoGebra software on pre-service mathematics teachers’ attitudes and views toward proof and proving. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 48(7), 1002–1022. [CrossRef]

- Putra, Z. H., Hermita, N., Alim, J. A., Dahnilsyah, & Hidayat, R. (2021). GeoGebra integration in elementary initial teacher training: The case of 3-D shapes. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 15(19), 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, K. K., Chang, C.-Y., & Huang, R. (2017). Integrating GeoGebra with TPACK in improving pre-service mathematics teachers’ professional development. In Proceedings of the IEEE 17th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT 2017) (pp. 313–314). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, E., & Arpaci, I. (2024). Understanding pre-service mathematics teachers’ intentions to use GeoGebra: The role of technological pedagogical content knowledge. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 18817–18838. [CrossRef]

- Munyaruhengeri, J. P. A., Umugiraneza, O., Ndagijimana, J. B., & Hakizimana, T. (2025). Exploring teachers’ perceptions of GeoGebra’s usefulness for learning limits and continuity: A gender perspective. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 11, 101412. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Xin, J. J., Yu, Z., Liu, Y., Zhao, W., Li, N., Li, Y., & Chen, G. (2025). Enhancing preservice teachers’ use of dialogic teaching and dynamic visualizations in mathematics classes: Bridging the knowing-doing gap. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, V. G. d., & Henriques, A. C. C. B. (2023). Pre-service mathematics teachers using GeoGebra to learn about instantaneous rate of change. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 54(4), 534–556. [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, M., & Yazici, N. (2021). Examining the digital learning material preparation competencies of preservice mathematics teachers. Participatory Educational Research, 8(3), 323–350. [CrossRef]

- Barna, O. V., Kuzminska, O. H., & Semerikov, S. O. (2025). Enhancing digital competence through STEM-integrated universal design for learning: A pedagogical framework for computer science education in Ukrainian secondary schools. Discover Education, 4, 357. [CrossRef]

- Marange, I. Y., & Tatira, B. (2024). Gender dynamics in GeoGebra integration: In-service mathematics teachers’ development. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 20(5), em2457. [CrossRef]

- Dilling, F., Witzke, I., Hornberger, K., & Trgalova, J. (2024). Co-designing teaching with digital technologies: A case study on mixed pre-service and in-service mathematics teacher design teams. ZDM – Mathematics Education, 56(4), 667–680. [CrossRef]

- Hohenwarter, M., Jarvis, D., & Lavicza, Z. (2023). GeoGebra’s global impact on mathematics education: Research, development, and practice. ZDM – Mathematics Education, 55(4), 701–715.

- Kasiram, M., & Muhassanah, N. (2024). Integrating GeoGebra in Indonesian secondary mathematics classrooms: Challenges and opportunities. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 36(2), 589–610.

- Chao, T., & Chen, Y. (2022). Fostering STEM competencies through dynamic geometry software: A design-based study with prospective mathematics teachers. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 31(5), 601–617. [CrossRef]

- Said, N. N., & Darmawan, D. (2023). GeoGebra-based learning to enhance mathematical reasoning and motivation among Indonesian high school students. International Journal of Instruction, 16(3), 421–438.

- López-Belmonte, J., Pozo-Sánchez, S., & Fuentes-Cabrera, A. (2020). Active and emerging methodologies for ubiquitous learning: Flipped classroom and GeoGebra. Mathematics, 8(12), 2231. [CrossRef]

- Saha, R. A., Ayub, A. F. M., & Tarmizi, R. A. (2021). The effects of GeoGebra on students’ achievement and attitude in learning mathematics: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 52(7), 1003–1020.

- Salleh, F. M., & Mat, N. (2024). TPACK development among pre-service teachers through GeoGebra-integrated lesson study. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 14(1), 112–127.

- García-Martín, J., & García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2025). Digital competence in STEM teacher training: A systematic review of technology integration models. Computers & Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100321.

- Wijaya, T. T., Purnama, Y., & Sulistiawati, R. (2022). The use of GeoGebra to improve students’ spatial ability in Indonesian vocational schools. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2215(1), 012032.

- Lavicza, Z., Hohenwarter, M., & Hoham, P. (2021). GeoGebra as a catalyst for research and innovation in mathematics education. International Journal for Technology in Mathematics Education, 28(4), 185–194.

- Siregar, T. (2025, October 15). Literature review: The use of GeoGebra software on mathematical comprehension ability. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, T. (2025, October 15). STEAM integration and mathematical problem solving: A meta-analysis of student learning outcomes in Indonesia. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, T. (2025). Application of GeoGebra for teaching mathematics. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, T. (2025). Integrating GeoGebra in mathematics education: Enhancing pedagogical practices among teachers and lecturers. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, T. (2025). Problem-solving skills (judul terkait pengembangan keterampilan pemecahan masalah dan model pembelajaran). Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, T. (2025, October 27). Analysis of mathematical literacy skills through the Think-Talk-Write (TTW) model assisted by GeoGebra in terms of students’ self-efficacy. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Jusniani, N., & Nurmasidah, L. (2021). Penerapan model pembelajaran generatif untuk meningkatkan kemampuan komunikasi matematis siswa. Jurnal Ilmiah Matematika Realistik, 2(2), 12–19. https://jim.teknokrat.ac.id/index.php/pendidikanmatematika/article/view/140.

- Kamilah, S. R., Budilestari, P., & Gunawan, I. (2019). Penerapan model pembelajaran Problem Based Learning (PBL) dengan berbantuan GeoGebra untuk meningkatkan kemampuan representasi matematis siswa SMK. Intermathzo: Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran Matematika, 4(2), 70–77.

- Kanah, I., & Mardiani, D. (2022). Kemampuan komunikasi dan kemandirian belajar siswa melalui Problem Based Learning dan Discovery Learning. Plusminus: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 2(2), 255–264. [CrossRef]

- Khasanah, U., & Nugraheni, E. A. (2020). Analisis minat belajar matematika siswa kelas VII pada materi segiempat berbantuan aplikasi Geogebra di SMP Negeri 239 Jakarta. Jurnal Cendekia: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 6(1), 181–190. [CrossRef]

- Khasinah, S. (2021). Discovery Learning: Definisi, sintaksis, keunggulan dan kelemahan. Jurnal Mudarrisuna: Media Kajian Pendidikan Agama Islam, 11(3), 402–413. [CrossRef]

- Lubis, R. A., Fitriani, N., & Sariningsih, R. (2023). Penerapan model Discovery Learning berbantuan E-LKPD untuk meningkatkan kemampuan komunikasi matematis siswa kelas X MA pada materi SPLTV. Jurnal Pembelajaran Matematika Inovatif, 6(4), 1473–1483.

- Luciana, N. (2021). Penerapan model Discovery Learning dalam meningkatkan kualitas pembelajaran dan hasil belajar matematika peminatan mengenai rumus jumlah dan selisih sinus dan kosinus dua sudut pada siswa kelas XI IPA 1 SMA Negeri 1 Cisaat. CENDEKIA: Jurnal Ilmu Pengetahuan, 1(2), 106–111. [CrossRef]

- Lutfiyah, L., & Sulisawati, D. N. (2019). Efektivitas pembelajaran matematika menggunakan media berbasis e-learning. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika (JUDIKA EDUCATION), 2(1), 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Maf, S., Wulandari, S., Jauhariyah, L., & Arif, N. (2021). Pembelajaran matematika dengan media software GeoGebra materi dimensi tiga. Mosharafa: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 10(3), 449–460.

- Millati, D. Y. I., & Prihaswati, M. (2020). Analisis minat belajar siswa pada materi SPTLDV berbantu aplikasi Geogebra. EDUSAINTEK, 4(0). https://prosiding.unimus.ac.id/index.php/edusaintek/article/view/537.

- Muhammad, I., & Juandi, D. (2023). Model Discovery Learning pada pembelajaran matematika sekolah menengah pertama: A bibliometric review. Euler: Jurnal Ilmiah Matematika, Sains dan Teknologi, 11(1), 74–88. [CrossRef]

- Nasution, N. A., & Lubis, M. R. (2021). Efektivitas pengembangan perangkat pembelajaran berdasarkan pembelajaran inkuiri berbasis budaya berbantuan Geogebra. AXIOM: Jurnal Pendidikan dan Matematika, 10(2), 133–142. [CrossRef]

- Novita, L., Windiyani, T., & Sakinah, A. R. (2020). Pengaruh penerapan model Discovery Learning terhadap hasil belajar matematika siswa. Widyagogik: Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran Sekolah Dasar, 7(2), 148–163. [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, L., & Setiawan, W. (2019). Analisis minat belajar matematika siswa SMA pada materi program linier berbantuan aplikasi Geogebra. Journal on Education, 2(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Patmawati, P., Ahmad, H., & Febryanti, F. (2022). Penerapan model pembelajaran Diskursus Multy Refrecentacy dengan aplikasi GeoGebra terhadap peningkatan kemampuan komunikasi matematis. Journal Peqguruang: Conference Series, 4(1), 302–309. [CrossRef]

- Pertiwi, F. A., Luayyin, R. H., & Arifin, M. (2023). Problem Based Learning untuk meningkatkan keterampilan berpikir kritis: Meta analisis. JSE: Jurnal Sharia Economica, 2(1), 42–49. [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, J. (2021). Kebermanfaatan penggunaan Geogebra dalam pembelajaran matematika. Idealmathedu: Indonesian Digital Journal of Mathematics and Education, 8(1), 9–22. [CrossRef]

- Fatihah, A., & Yahfizham, Y. (2024). Penerapan GeoGebra terhadap kemampuan pemecahan masalah matematis siswa dalam pembelajaran matematika. Pendekar: Jurnal Pendidikan Berkarakter, 2(3). [CrossRef]

- Hayati, Z., & Ulya, K. (2022). Developing students’ mathematical understanding using GeoGebra software. Jurnal Ilmiah Didaktika: Media Ilmiah Pendidikan dan Pengajaran, 22(2). [CrossRef]

- Irvan, I. (2024). Application of integrals in calculating ball volume using GeoGebra. Indonesian Journal of Education and Mathematical Science, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Thomas Jr., G. B., Weir, M. D., & Hass, J. R. (2014). Thomas’ Calculus (13th ed.). Pearson.

- Kado, & Dem, N. (2020). Effectiveness of GeoGebra in developing the conceptual understanding of definite integral at Gongzim Ugyen Dorji Central School, Haa, Bhutan. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 60–65. [CrossRef]

- Maf’ulah, S., Wulandari, S., Jauhariyah, L., & Ngateno. (2021). Pembelajaran matematika dengan media software GeoGebra materi dimensi tiga. Mosharafa: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Meldi, N. F., Khoriyani, R. P., Susanti, W., Ahmad, D., & Rif’at, M. (2022). Implementasi teknologi digital dalam perkuliahan mata kuliah kalkulus integral dalam penyelesaian luas daerah antarkurva. Jurnal Alwatzikhoebillah: Kajian Islam, Pendidikan, Ekonomi, Humaniora, 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. SAGE Publications.

- Nasution, A. E., Irvan, I., & Batubara, I. H. (2020). Penerapan model Problem-Based Learning dan etnomatematik berbantuan GeoGebra untuk meningkatkan kemampuan komunikasi matematis. Journal of Mathematics Education Sigma (JMES), 1(2). [CrossRef]

- Nongharnpituk, P., Yonwilad, W., & Khansila, P. (2022). The effect of GeoGebra software in calculus for mathematics teacher students. Journal of Educational Issues, 8(2), 755–770.

- Nuratifah, S., T., A. Y., Siregar, N., & Meldi, N. F. (2024). Peran aplikasi GeoGebra dalam kemampuan representasi visual matematis siswa pada materi fungsi. J-PiMat: Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Sofyan, D., Puspitasari, N., Maryati, I., Basuki, B., & Madio, S. (2020). The effects of GeoGebra on problem-solving skills in integral calculus. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Islam, Science and Technology (ICONISTECH 2019), 11–12 July 2019, Bandung, Indonesia. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J. (2020). Calculus: Early transcendentals (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. https://openlibrary.telkomuniversity.ac.id/pustaka/159921/calculus-early-transcendentals-8-e-.html.

- Subagio, L., Karnasih, I., & Irvan, I. (2021). Meningkatkan motivasi belajar siswa dengan menerapkan model Discovery Learning dan Problem-Based Learning berbantuan GeoGebra. Jurnal Pendidikan Matematika Raflesia, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Sugiyono, & Suryandari, S. Y. (2017). Metode penelitian kualitatif: Untuk penelitian yang bersifat eksploratif, interpretif, interaktif, dan konstruktif (1st ed.). Alfabeta.

- Tasman, F., & Ahmad, D. (2018). Visualizing volume to help students understand the disk method in integral calculus course. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 335(1), 012112. [CrossRef]

| No | Curve | Interval | Axis | Method | Analytical Volume | Volume Geogebra | Selisih (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | y=x2 y = x2 |

[0,2] | X | Disk | 20,096 | 20,11 | 0,069666 |

| 2 | y = 2x + 1 | [0,3] | X | Disk | 178,98 | 179,07 | 0,050285 |

| 3 | y = sin (x) | [0,n] | X | Disk | 4,9298 | 4,93 | 0,004057 |

| 4 | y=x2 y = x2 |

[0,2] | Y | Shell | 25,12 | 25,13 | 0,039809 |

| 5 | y = 2x + 1 | [0,3] | Y | Shell | 141,3 | 141,37 | 0,04954 |

| 6 | y = sin (x) | [0,n] | Y | Shell | 19,7192 | 19,74 | 0,105481 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).