Introduction

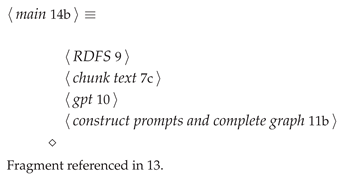

Several choices have been made, in terms of implementation, over the course of this project which should be reviewed individually for the clearest understanding of the work as a whole. Specifically in this section we will give an overview of the Semantic Web, the use of Resource Description Framework (RDF) file, Large Language Models (LLMs), the LLM (GPT-4o) we used, and also some further information on the sort of financial disclosure documents we used in order to better understand the data modelling choices. Finally, this paper itself is written using the nuweb Literate Programming framework. For the benefit of readers unfamiliar with this approach to authoring software and its documentation this section concludes with a brief meta overview on the creation of this paper.

The Semantic Web

The Semantic Web, as originally envisioned by Tim Berners-Lee, is an extension of the World Wide Web that enables machines to understand and interpret the data available on the internet. Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of both, introduced the concept of the Semantic Web in the late 1990s with the aim of creating a more intelligent and interconnected web. As originally conceived, the Semantic Web would go beyond the simple connecting of HTML documents to become a web of data, where information is given well defined meaning (semantics), facilitating integration and collaboration across individuals and institutions. This enhanced web would allow for data to be shared and reused across various applications, enterprises, and community boundaries. [

2] The argument that the World Wide Web has become less, and not more, open in the subsequent decades is not a difficult one to make. Still, although not widespread the original spirit is not entirely lost. Projects such as DBpedia [

2], Schema.org [

10], BioPortal [

12], and DOLCE [

9] are modern examples of the intentions of the Semantic Web.

At the core of the Semantic Web is the idea of linking data in a way that is understandable not only to humans but also to machines. Specifically, HTML is designed for the display of documents with no concern for the semantics of the content. The Semantic Web addresses these limitations. This involves the use of standardized formats, ontologies, and metadata to describe the relationships between different data. Technologies such as RDF (Resource Description Framework), OWL (Web Ontology Language), and SPARQL (SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language) are the main components of implementation.

RDF and RDFS

The Resource Description Framework (RDF) is a standard model for data interchange on the web. Developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) [

11], RDF provides a framework for representing information about resources in a structured, machine readable way. RDF is designed to facilitate data merging even if the underlying schemas differ and to support the evolution of schemas over time without requiring all the data consumers to be changed.

RDF represents information using a graph-based structure, consisting of triples. Each triple has three components: (1) Subject: The resource being described. (2) Predicate: The property or relationship of the resource. (3) Object: The value of the property or another resource. For example, a triple might represent the statement “Alice knows Bob”with “Alice”as the subject, “knows”as the predicate, and “Bob”as the object. RDF uses URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers) to uniquely identify subjects, predicates, and objects, ensuring unambiguous references across different data sources. The RDF graph structure is sometimes referred to as a Semantic Knowledge Graph (SKG), a term we will make use of.

RDF data can be serialized in various formats, including RDF/XML, Turtle, N-Triples, and JSON-LD, each offering different levels of readability and compactness. In this project we have exclusively used Turtle format [

6].

RDF Schema (RDFS) is a semantic extension of RDF that provides mechanisms for describing groups of related resources and the relationships between them. RDFS offers basic vocabulary to structure RDF data and to define classes and properties, facilitating more sophisticated data modeling and reasoning [

3].

There are several key features of RDFS: (1) Classes and Subclasses: RDFS allows the definition of classes (i.e. types of resources) and subclasses (i.e. hierarchical relationships between classes). For example, one might define a class “Person”and a subclass “Employee”. (2) Properties and Subproperties: Properties are defined to describe relationships between resources. Subproperties allow for the creation of property hierarchies. For example, “hasParent”could be a subproperty of “hasFamilyMember”. (3) Domain and Range: These constraints specify the types of subjects (domain) and objects (range) that a property can have. For example, the property “hasChild”might have a domain of “Person”and a range of “Person”.

In this way RDFS enriches RDF data with a schema layer that adds semantic context, allowing for more intelligent data retrieval and manipulation. By defining these structures, RDFS enables machines to infer additional information from the data, improving the capabilities of applications that consume RDF data. For example, in the context of a bibliographic database, RDF can represent metadata about books, authors, and publishers. RDFS can then define the classes such as “Book”, “Author”, and “Publisher”and properties such as “writtenBy”and “publishedBy”. This structured representation allows for queries conceptually like “Find all books written by authors who have published more than five books with Publisher P”, leveraging the inferencing capabilities provided by the schema.

OWL (Web Ontology Language) is another framework used in the Semantic Web for defining and organizing structured data with semantic schemas [

1]. Generally stated, it extends RDFS to allow for even richer descriptions and is arguably more well suited for modelling complex relationships. We do not use OWL in the current work, although we will make brief mentions of it later.

A key point from the above is that RDF is an inherently computable file format for structured data. The structure of that data can be described using RDFS. Although there are certainly many other formats that could be used for representing structured data we intend to also allow for meaningful semantics to be represented. Thus we feel that RDF is an excellent choice for our purposes. Additionally, as we will eventually illustrate, the nature of SPO triples allows for self-reasoning or reflection of the SKG.

Large Language Models

Large language models (LLMs) are a recent advancement in the field of natural language processing (NLP). These models, built on neural network based Deep Learning frameworks, are characterized by their massive size and complex architectures. They have captured the public imagination in their seeming abilities to understand, generate, and manipulate human language in a way that closely mimics human communication [

7]. LLMs such as OpenAI’s GPT models, Meta’s Llama project, and Google’s Gemini are trained on vast amounts of text data. This is something of a point of controversy as the exact data sources are largely kept secret. What is known is that, generally, all publicly accessible information on the World Wide Web is used, along with proprietary sources made via licensing arrangements. The controversial aspect is based on the view that copyright holders are being unfairly treated for what can be seen as uncompensated labor. Still, this extensive training allows for a wide range of applications from automated text generation and translation to question answering tasks [

5].

The key to the effectiveness of large language models lies in their ability to learn contextual relationships between words and phrases across large corpora. This is achieved through techniques such as transformer architectures, which leverage mechanisms like self-attention to weigh the importance of different words in a sentence relative to each other. The result is a model that can generate coherent and contextually relevant text that often appears human like. Appearances are, of course, deceiving. The most well known deployments of LLMs in applications such as search have, as of this writing, seemingly only generated curiosity with a lot of attention in the popular media focussed on their shortcomings. The main drawback is from LLMs so called hallucinations which is the generation of plausible but false text. The appearance of reasoning in LLMs is an active area of study but at present it seems that LLMs sense of semantics is shallow, although their strong abilities to detect statistical patterns in text provides a convincing cover. This paragraph is the opinion of the author based on information current at the time of this writing. At present there exist no studies which quantify, much less explain, the ability of LLMs to reason or understand semantics.

We observe that while LLMs abilities to reason and understand text semantics is at best controversial, that the extant Semantic Web technologies provide ample facilities in these areas.

GPT-4o

GPT-4o is the, as of this writing, latest iteration in OpenAI’s line of Generative Pre-trained Transformers. This model builds on the architecture and training methods of its predecessors. GPT-4o is designed to generate more contextually appropriate and syntactically coherent text outputs for more general topics than earlier versions. [

13]

Example Corpus

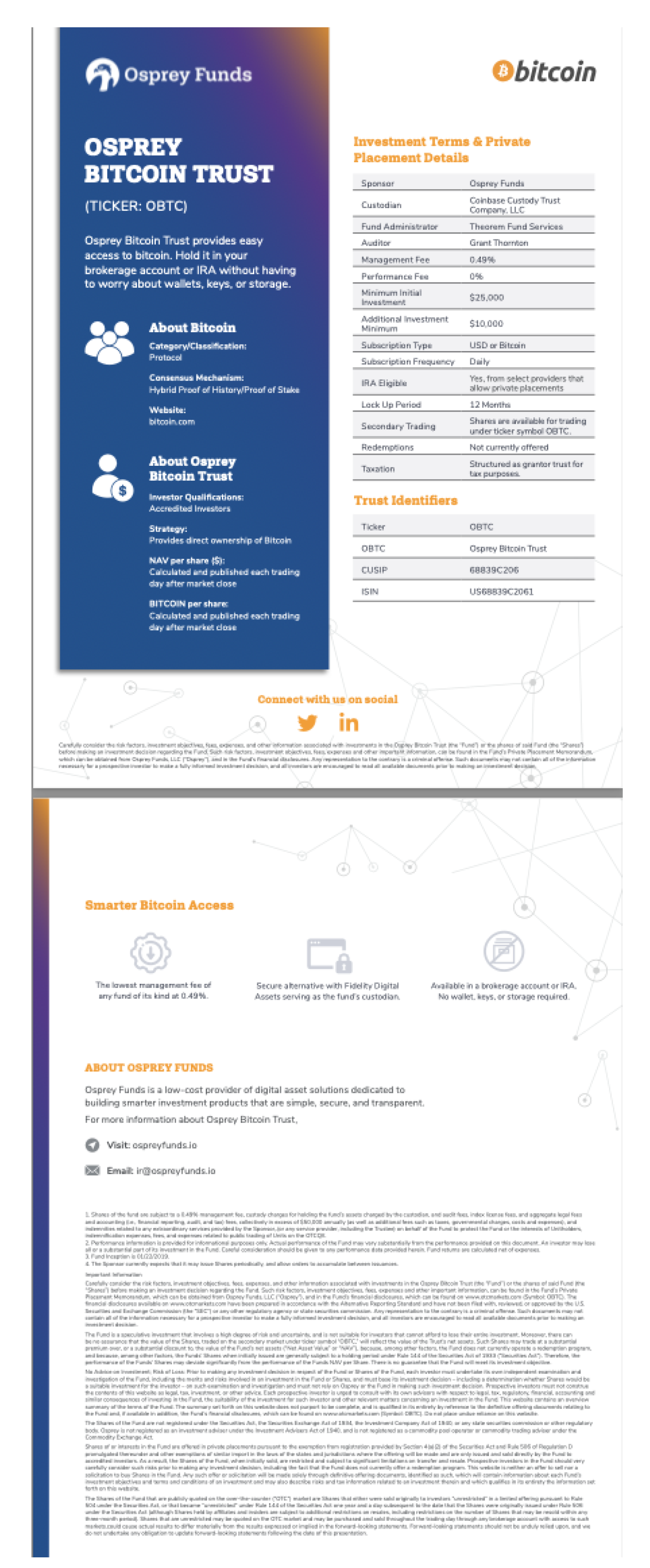

As an example of unstructured data we will be using a financial fact sheet for an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF). This ETF is the Osprey Bitcoin Trust (Ticker:OBTC) [

8]. This sort of document was chosen as it contains an amount of information suitable for a focussed example of “real life”data and is amenable to the applications common to Semantic Knowledge Graphs. We should note that this is not an example of a full prospectus. This document is more similar to a “product description”which, broadly speaking, is itself an interesting target for SKG applications.

Literate Programming with Nuweb

Nuweb is a tool designed for literate programming, a programming paradigm introduced by Donald Knuth that mixes code and documentation together within the same documents. With nuweb, authors can write programs in a narrative style, embedding executable code within descriptive text. Nuweb supports multiple programming languages and offers features like automatic indexing and cross referencing, making it easier to navigate large codebases. By combining documentation with source code, Nuweb facilitates a deeper understanding of the program’s logic and design. [

4]. In the remaining sections of the paper code will be interspersed with descriptive explanations.

Figure 1.

The OBTC financial fact sheet.

Figure 1.

The OBTC financial fact sheet.

Methodology

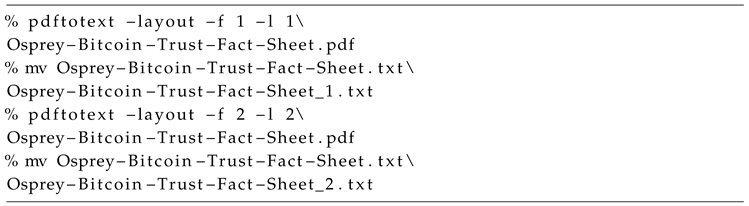

PDF to Text Conversion

The most common format for public financial information is PDF. For our purposes we use the pdftotext utility to preprocess the data into a plain text format.

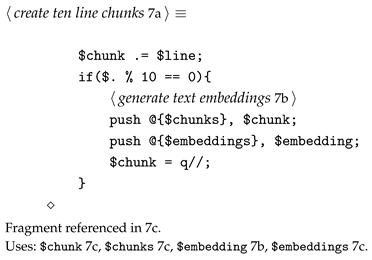

We rely on minimal knowledge of the document, only that it is two pages in length. This is the first part of our

chunking strategy [

15].

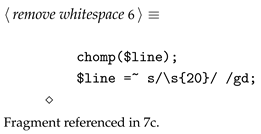

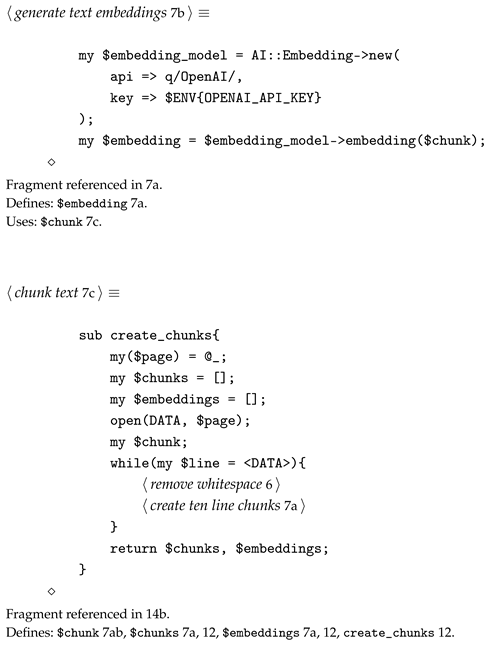

A side effect of removing the text from the pdf is the introduction of a good deal of extra whitespace. Let’s remove it. Anything over, say, 20 spaces can safely be considered noise in this use case.

Document Schema

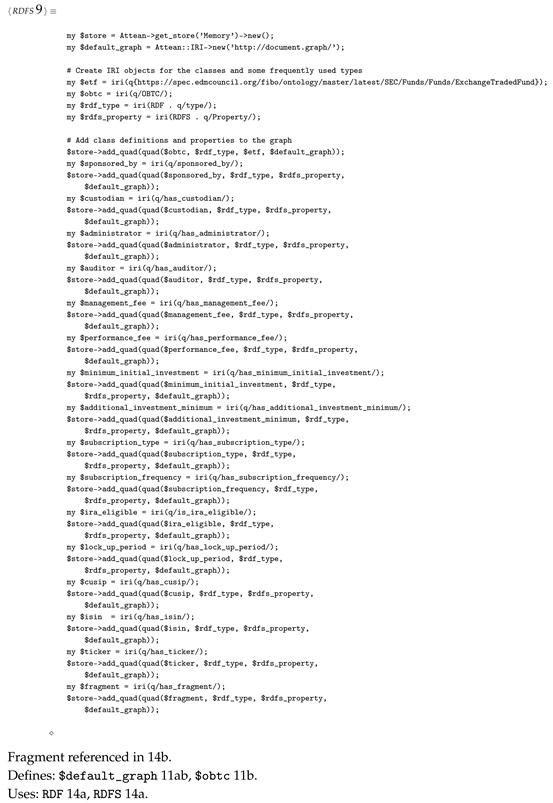

When presented with the task of representing financial documents in RDF there are several existing ontologies that may be used, in addition to our own custom schemas. Here we make some use of the Financial Industry Business Ontology (FIBO) [

14] as well as our own RDFS definitions. This choice is done to balance formalism and rigor with clarity of presentation. This is well within the spirit if the Semantic Web, we may choose as little or as much from existing ontologies as needed by an application.

Ask the LLM

A reflection of the AI zeitgeist: we find it most convenient to call OpenAI’s GPT. This is configured to use GPT-4o.

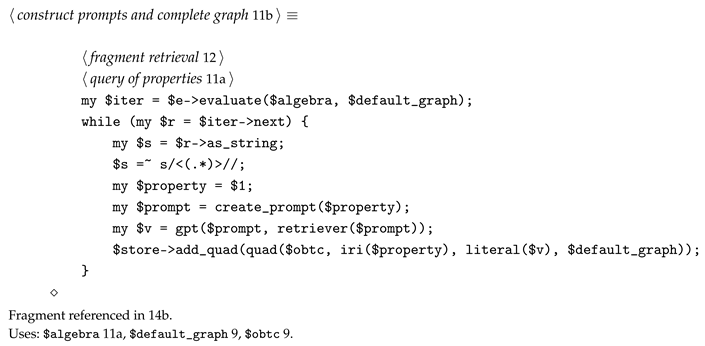

Prompt Construction for Graph Construction

Now we have almost all the necessary pieces to use our RDFS to generate prompts and complete the Knowledge Graph for our document.

In our present use case we’ve generated RDFS properties, these could have just as well been from pre-written RDFS. More complex ontologies could similarly be obtained from an OWL ontology.

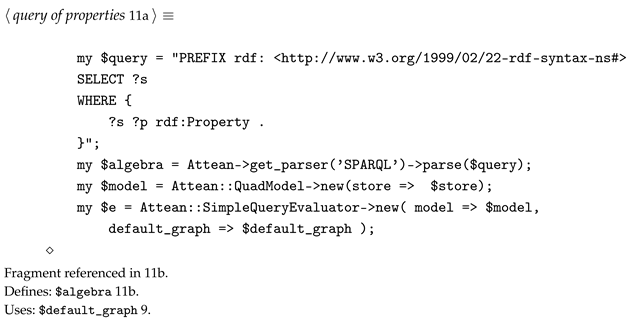

To begin with we use these properties, as obtained from a SPARQL query, as a starting point.

Discussion and Conclusions

We have developed a Knowledge Graph application which does the following:

Defined RDFS for a class of financial documents. This RDFS could also have come from a pre-defined RDFS source. Alternatively, OWL could also have been used.

Chunked an input document.

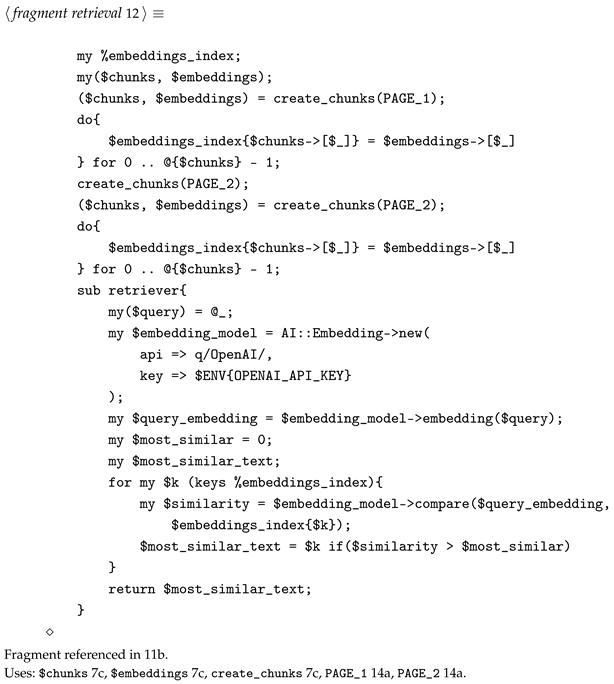

Defined a RAG function for the document fragments.

Queried the RDFS properties and used them to generate LLM prompts.

Those prompts were used to retrieve the document chunks most likely to contain the answer to the propt question.

An LLM was sent the prompts and relevant text chunks to extract the requested information.

The LLM response was used to complete the Knowledge Graph in accordance with the RDFS.

The results are compelling but have the standard limitations of any prototype application. Noteworthy examples are: our not requiring the use of additional date types and the related checking of LLM responses that would require, the relative simplicity of our RDFS, the trust in web based APIs which are subject to network and other service disruptions, and the need for improvements of our text chunking and RAG functionality, both of which use standard basic approaches which are fit for many purposes but lack scalability and resilience. In particular, we note that the construction of prompts can be greatly improved by making an intermediate LLM call to generate a more complex phrasing, instead of the limitations of using the property terms directly. This would allow for increased variety to property names.

Next directions are to address the previously stated limitations as well as begin to examine the work required to bring this methodology to additional knowledge domains. The sort of documents examined here are representative of many unstructured real world texts, but in some fields such as law and medicine the complexity of texts is much greater and addressing that complexity is likely to be a deep source of future work.

Appendix A. Code

All code not directly relevant to the discussion in the main body of the paper is contained here.

References

- Sean Bechhofer, Frank van Harmelen, Jim Hendler, Ian Horrocks, Deborah McGuinness, Peter Patel-Schneijder, and Lynn Andrea Stein. OWL Web Ontology Language Reference. Recommendation, World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), February10 2004. See http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-ref/.

- Tim Berners-Lee, James Hendler, and Ora Lassila. The Semantic Web, volume 284. Scientific American, 2001.

- Dan Brickley and R.V. Guha. RDF Vocabulary Description Language 1.0: RDF Schema. W3C Recommendation, World Wide Web Consortium, February 2004.

- Preston Briggs. Nuweb, a simple literate programming tool. |cs.rice.edu:/public/preston|, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA, 1993.

- Tom Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared D Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Sandhini Agarwal, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Gretchen Krueger, Tom Henighan, Rewon Child, Aditya Ramesh, Daniel Ziegler, Jeffrey Wu, Clemens Winter, Chris Hesse, Mark Chen, Eric Sigler, Mateusz Litwin, Scott Gray, Benjamin Chess, Jack Clark, Christopher Berner, Sam McCandlish, Alec Radford, Ilya Sutskever, and Dario Amodei. Language models are few-shot learners. In H. Larochelle, M. Ranzato, R. Hadsell, M.F. Balcan, and H. Lin, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 33, pages 1877–1901. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020.

- Gavin Carothers and Eric Prud’hommeaux. RDF 1.1 turtle. W3C recommendation, W3C, February 2014.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019.

- Osprey Funds. OSPREY BITCOIN TRUST: Investment Terms & Private Placement Details. https://ospreyfunds.io/wp-content/uploads/Osprey-Bitcoin-Trust-Fact-Sheet.pdf, 2019. [Online; accessed 26-May-2024].

- Aldo Gangemi, Nicola Guarino, Claudio Masolo, Alessandro Oltramari, and Luc Schneider. Sweetening Ontologies with DOLCE, pages 166–181. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2002.

- Ali Khalili and Sören Auer. Wysiwym authoring of structured content based on schema.org. In Xuemin Lin, Yannis Manolopoulos, Divesh Srivastava, and Guangyan Huang, editors, Web Information Systems Engineering – WISE 2013, volume 8181 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 425–438. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013.

- Ora Lassila and Ralph R. Swick. Resource Description Framework (RDF) Model and Syntax Specification. Technical report, 1999.

- Natalya F. Noy, Nigam H. Shah, Patricia L. Whetzel, Benjamin Dai, Michael Dorf, Nicholas Griffith, Clement Jonquet, Daniel L. Rubin, Margaret-Anne Storey, Christopher G. Chute, and Mark A. Musen. BioPortal: ontologies and integrated data resources at the click of a mouse. Nucleic Acids Research, 37(suppl_2):W170–W173, 05 2009. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Gpt-4 technical report, 2024.

- GG Petrova, AF Tuzovsky, and Nataliya Valerievna Aksenova. Application of the financial industry business ontology (fibo) for development of a financial organization ontology. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, volume 803, page 012116. IOP Publishing, 2017.

- Roie Schwaber-Cohen. Chunking Strategies for LLM Applications. https://www.pinecone.io/learn/chunking-strategies/, 2023. [Online; accessed 2-June-2024].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).