1. Introduction

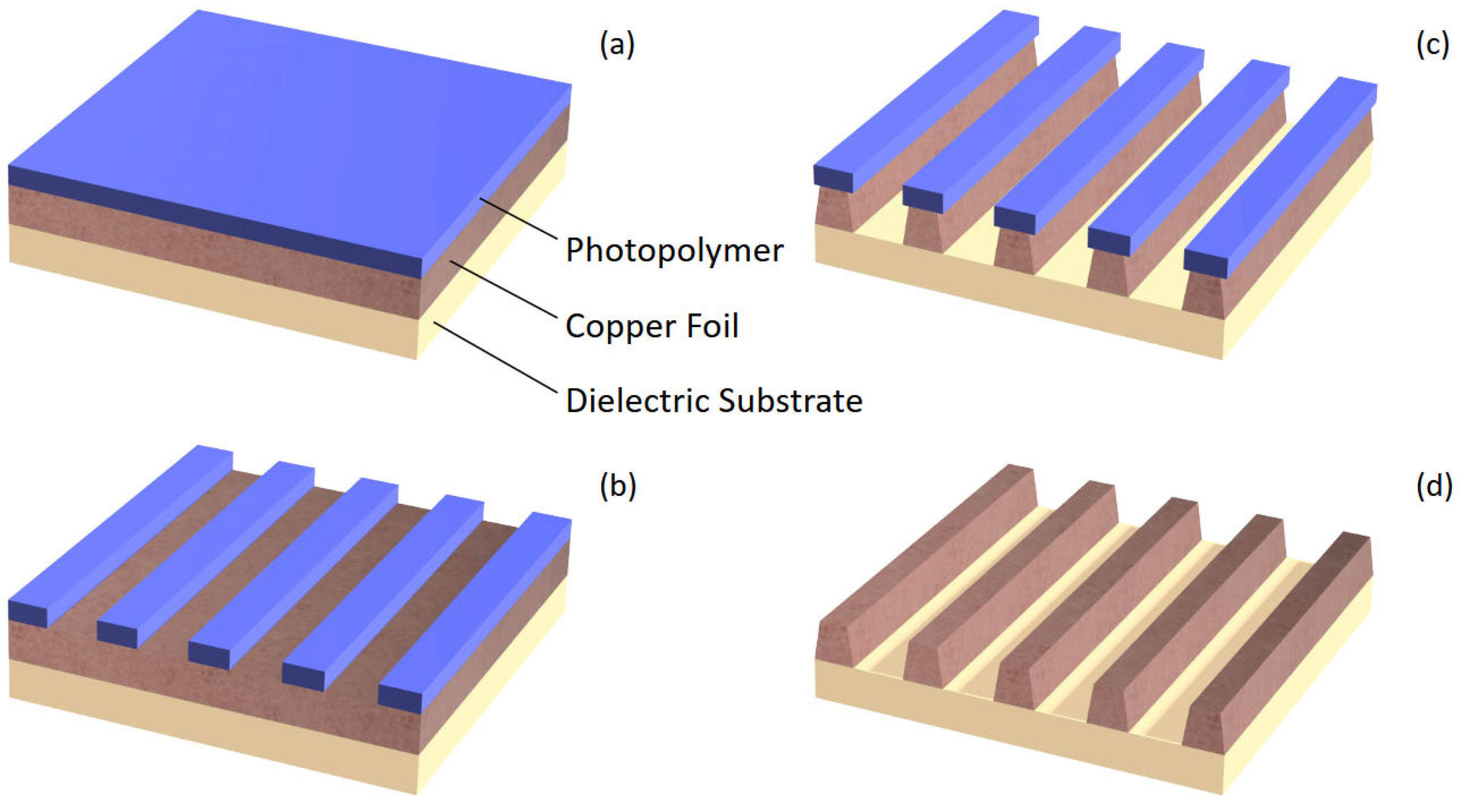

Chemical machining, beginning as an ancient technique to produce copper jewelry, was heavily advanced during the 1900s by the electronics industry for application in the manufacture of conductors on printed circuit boards, lead frames of semiconductor devices, and other electronic components [

1,

2]. In these modern applications, both photographic and chemical techniques are employed sequentially, a process termed photochemical machining, to selectively remove the area to be machined (

Figure 1): the workpiece is coated with a photoactive polymer, areas to be retained are exposed and developed, then the undesired material is chemically machined, leaving material retained only in areas protected beneath the photopolymer [

1,

2,

3]. In general, this process is known by many names including etching, wet etching, photoetching, photochemical milling, photoengraving, and chemical micromachining among others depending on context [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Chemical machining of Group 11 elements (Cu, Ag, Au) by this solution method has the comparative advantages of lower capital investment costs for tools, independence from physical properties of the workpiece, high selectivity regarding other films and materials in device structures, and high precision on micrometer scales [

2,

5]. These methods are not suitable, however, on nanometer scales where controlled profiles are required for advanced microelectronics, due to the isotropic nature of chemical machining [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Machining by liquid, as well as by gaseous and vapor-phase etchants, is generally isotropic, having a non-zero etching rate in all directions [

2,

5]. As microcomponents are advanced toward smaller dimensions, the thickness of the material becomes comparable to the lateral pattern dimensions to the extent which the lateral etching imparted by isotropy of the etchant may become intolerable or difficult to control [

4,

7,

8]. This has been noted as the most influential factor in fabricating three-dimensional microcomponents of micro-electromechanical systems [

4]. For this reason, chemical machining equipment is usually designed with pressurized sprays impacting the workpiece with etchant perpendicularly, which has been shown to give some preference to vertical etching over the lateral direction [

3,

6,

9]. Several mathematical models have been developed which simulate the isotropic nature of chemical machining [

10,

11,

12].

Alternative process have been developed toward anisotropic machining at nanometer scales with nearly vertical side walls, using machining agents such as ion beams, laser and high-intensity photon sources, and plasmas [

1,

5]. Although, these methods pose a much greater expense which keeps chemical machining a more viable option when pattern dimensions would tolerate its degree of isotropy. Additionally, chemical machining generally provides greater etching rates and selectivity [

1]. Common etchants used for photochemical machining are transition metal salts: acidic ferric chloride, acidic cupric chloride, and alkaline cupric ammine chloride; others include chromic-sulfuric acid, ammonium persulfate, and hydrogen peroxide with sulfuric acid [

1,

4]. The transition metal salts have the comparative advantages of greater reaction rates and the capability to be regenerated for a steady-state system [

1,

2,

13]. This is especially true for cupric chloride, where reaction products maintain the bath composition so long as chloride is kept in excess, but less true for ferric chloride, where reaction products change the bath composition from its starting condition as dissolved copper species accumulate [

1,

2,

13].

In production of multi-layered printed circuit boards, conductors are connected between layers by a through-hole plating process typically utilizing metallic resist during machining, such as a tin-lead alloy, rather than a photopolymer [

1]. Selectivity is therefore required of the etchant to remove copper while preserving the metallic resist. Among the three noted etchants of transition metal salts, alkaline cupric ammine chloride provides the greatest etch rate and capacity for dissolved copper with the selectivity needed to preserve tin and tin-lead alloy resists. Although, these benefits come by greater operation and copper recovery costs [

2,

4,

13]. In contrast, acidic cupric chloride is favored due to its lower costs and chemical simplicity in machining and regeneration, but it exhibits the slowest etch rate of the three without selectivity for copper, limiting its typical application in printed circuit board manufacturing to chemical machining of individual layers [

2,

4,

13,

14,

15]. Ferric chloride is a universal metal etchant which has decreased in popularity for high-volume machining of copper due to its lower capacity for dissolved copper than acidic cupric chloride, despite usually having greater etch rates [

2,

4,

13,

15,

16].

The chemical machining principle is known to involve two sequential stages: oxidation of the metal surface followed by solvation of the oxidation products [

5,

17]. Therefore, the overall rate of etching is not only dependent on the intrinsic redox reaction but also on the dissolution of oxidation products from the metal surface. While reduction of the Cu(II) metal center of reacting etchant is observed to occur exclusively through two successive, one-electron transitions between Cu(II) and Cu(0) [

18,

19], oxidation of the solid copper workpiece is more intricate. Two-step oxidation is seen near the open-circuit potential in acidic chloride solutions [

18], while solid copper in alkaline ammine solutions exhibits two-step oxidation only for thin layers of electroplated copper electrodes tested from 0.03-µm thickness [

19]. As thickness of the plated layer approached 0.40 µm in these alkaline solutions, surface reactions dependent on ammonia concentration were detected after oxidation of solid copper to copper(I). Two-step behavior returned only when the ammoniacal buffer concentration increased to 3 M, further supporting an indication of passive cuprous compounds obstructing the surface from simple, two-step oxidation [

19]. Limitations on the redox behavior are therefore evident when using copper electrodes or when using greater ratios of copper-to-ammonia, which are not seen using vitreous carbon electrodes [

19].

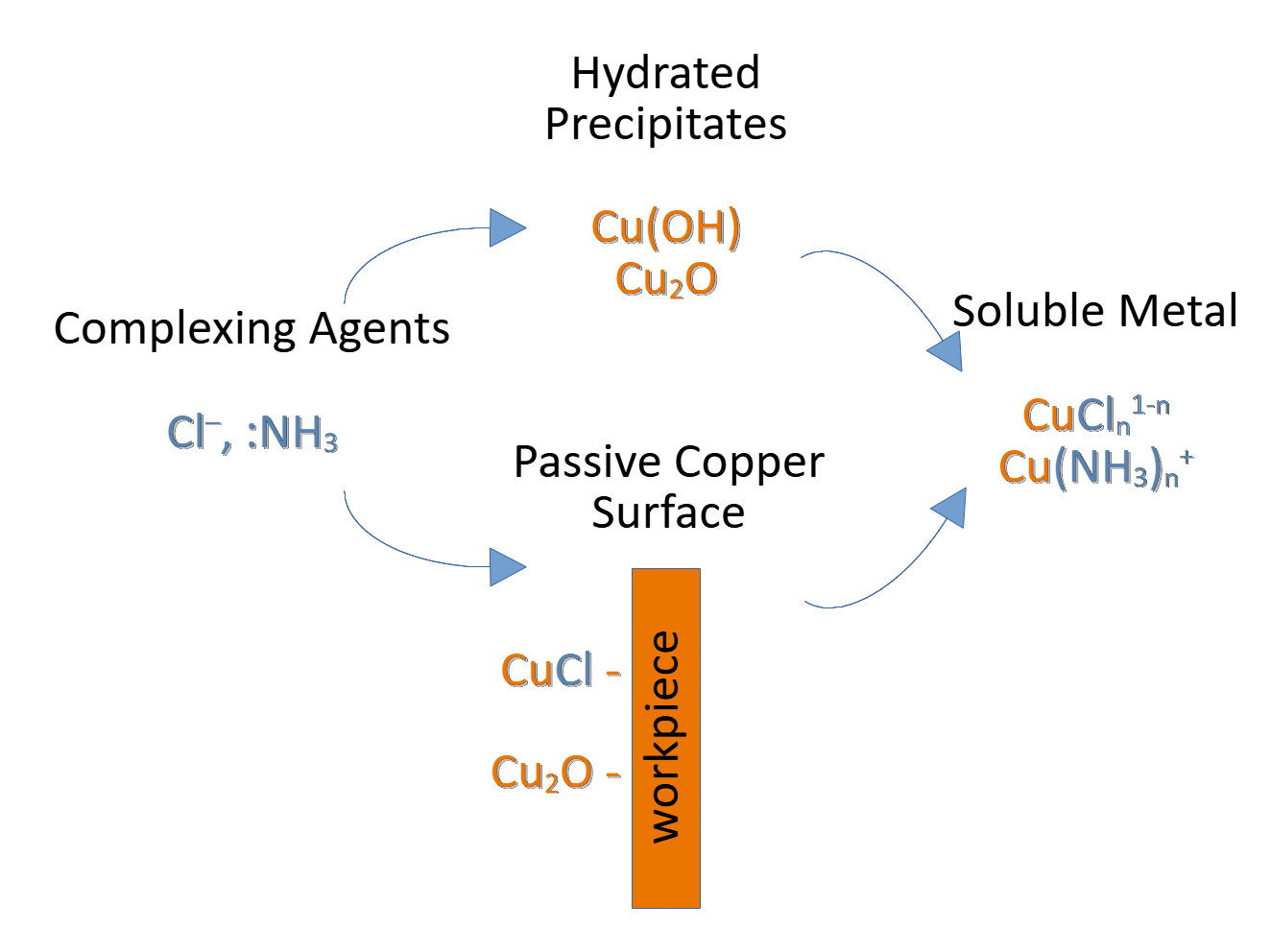

Indeed, passivation of the copper surface by films of insoluble cuprous compounds formed from its oxidation is known to occur in both acidic and alkaline solutions and poses the greatest impediment to the chemical machining process, with dissolution of the films being the slowest step in the overall machining mechanism [

14,

16,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Ligands, commonly chloride and ammonia, are included in the etchant salt and supplemented by acids or additional ionic salts, as they are necessary to maintain the machining process by coordinating passive species to dissolve the film [

5,

16,

20,

26]. The bidirectional diffusion limitation at the copper surface imposed by its passivity in conjunction with viscosity arising from high ionic strength and specific gravity of industrial etchants makes industrial chemical machining reactions generally mass transfer-limited and diffusion-controlled [

3,

7,

20,

24,

27].

Essential to the goal of optimizing systems for anisotropic chemical machining is to establish an understanding of its limiting mechanisms. This review draws from supporting literature to elaborate industrial implications of passivity and the factors which lead to challenges observed in maintaining soluble metal ions.

2. Passivation and Film Dissolution

Passivation of copper surfaces by films of insoluble cuprous compounds formed from its oxidation poses the greatest impediment to the chemical machining process, with film dissolution being under mass transport control and the slowest step in the overall machining mechanism [

14,

16,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Specifically, the rate-determining step is postulated to be either diffusion of complexing agents to the surface [

24] or diffusion of dissolved oxidation product complexes away from the surface [

21,

28]. Limitation is especially large in the case of alkaline ammine etchant, where surface processes involve the formation and dissolution of multiple passive species controlling the etch rate [

19,

25]. The requirement that etchant salts deliver effective ligands in order to maintain the etching process is apparent. For example, copper sulfate does not act as a copper etchant in the absence of ligands such as chloride and ammonia, likely because it cannot effectively coordinate oxidized cuprous products following electron transfer [

17,

29,

30].

By spectroscopic techniques, usually X-ray methods, passivation of copper surfaces in these chloride solutions is known to occur by the formation of insoluble layers of cuprous chloride [

31,

32,

33], CuCl, with the additional formation of cuprous oxide, Cu

2O, in alkaline solutions [

25]. In the absence of passivity, bare copper at the material surface contacts etchant directly without obstruction. Following electron transfer, if the dissolution rate of CuCl is less than its generation rate, CuCl film accumulates over time, posing a bidirectional diffusion limitation which obstructs further reaction [

34]. As a result, the effective redox rate and of consequent generation of CuCl film decreases until reaching the dissolution rate of CuCl, thereby establishing dynamic equilibrium which stabilizes the overall etching rate [

16,

23].

The function of complexing agents (chloride and ammonia in these cases) to dissolve these passive oxidation products is described in this section. Passivation behavior and the associated dissolution process is equivalent in ferric chloride and cupric chloride etchant, and so their description in this section is considered for acidic chloride solutions in general.

2.1. Alkaline Cupric Ammine Chloride

Passivation in alkaline ammine chloride solutions involves the generation of film layers consisting primarily of CuCl but with the hydrolysis product Cu

2O also present in significant quantity and proposed to form by heterogeneous surface reactions as well as by homogeneous hydrolysis of soluble cuprous chloride species, Reaction (6) [

25,

30]. Most literature regarding passivation in this environment pertains to electrochemical machining, which applies an external bias to induce anodic dissolution and limits its application to chemical machining, where dissolution occurs at the open-circuit potential. However, passivation during electrochemical experimentation is found to occur even at thermodynamically unfavorable electrode potentials, indicating chemical mechanisms of formation immediately following the oxidation of solid copper to copper(I) in addition to the electrochemical paths most often observed .These layers formed chemically seem to exhibit lesser adhesion to the copper surface, being observed to “flow off” while electrodes remain coated in a thin, passive oxide layer [

25,

30]. As the challenge imposed by passivity is largely related to mass transport, this property then seems to suggest that mechanical agitation may offer some advantage. In fact, success has been found in reducing some of the impact of this loosely-bound film on machining rates by strong agitation or greater rotation speed of rotating disk electrodes [

23,

25]. Industrially, this gives necessity to etchant application by pressurized sprays, since the etching rate would be expected to decline otherwise or result in poor uniformity at insufficient spray pressures. Additional challenges are also faced in detection as both transient and persistent, solid compounds are formed [

17,

19,

25,

36]. Although, increasing the ratio of copper-to-ammonia is known to favor the formation of transient precipitates [

19].

The dissolution of passive cuprous compounds in ammine solutions is slow and most strongly dependent on the concentration of free ammonia, which functions as a complexing agent in dissolving the passive species as well as slowing their rate of generation, forming only Cu(NH

3)

2+ and Cu(NH

3)

3+ over a large concentration range [

19,

25,

30,

36]. The use of ammonium chloride also improves the copper etching rate relative to ammonium sulfate solutions [

29], indicating that chloride complexes as well may serve some function to either dissolve or prevent formation of cuprous oxide in addition to its known role in dissolving the passive cuprous chloride film which becomes dominant in the presence of chloride [

25]. Although the accelerating effect of chloride complexes has been attributed to the lesser kinematic viscosity and greater diffusion coefficient in ammonium chloride than ammonium sulfate, these observations may be related.

Overall, passivation in cupric ammine chloride is complicated by competing ligands involved in the system in addition to the inclination toward hydrolysis in alkaline environments. However, not much attention seems to have been given toward a mechanistic description of the role of mixed coordination complexes in these solutions. Ternary complexes of copper(I) ammine chloride are known to form in addition to binary complexes of copper(I) ammine and copper(I) chloride [

37]. Further study may benefit from a detailed comparison of speciation and the specific actions each of chloride, ammine, and mixed coordination complexes [

38] in regard to passivation in this common etchant.

2.2. Acidic Chloride Solutions

In contrast to alkaline cupric ammine, the insoluble, passive layer formed immediately following oxidation of solid copper in acidic chloride solutions is comprised only of CuCl, a white solid [

31,

32,

33]. It has been postulated that ferric chloride can oxidize this copper(I) chloride surface film directly to soluble copper(II) chloride [

16], but the conjecture is not well founded in supporting literature. Rather, dissolution of the passive film is generally understood to require, first, diffusion of chloride to the film surface, adsorption and complexation of the chloride ligands, then dissolution of the coordinated copper(I) species away from the surface [

17,

18,

21,

23,

24,

39]. Furthermore, there is strong indication that passive species dissolve as CuCl

2– before further coordination [

18,

21,

22,

23,

28], as copper(I) predominantly exists as CuCl

32– in acidic chloride solutions [

24,

40,

41]. Mathematical models have been developed which predict this diffusion process with steady-state film thickness and dissolution rate under potentiostatic conditions [

39,

42], and a reaction coordinate diagram has been recently published for the sequential coordination of adsorbed CuCl up to CuCl

32– using density functional theory (DFT) calculations under an implicit water solvent [

17].

While the chloride anion serves the essential function to maintain the chemical machining process by coordinating dissolved copper, not all chloride sources facilitate copper etching. Non-coordinating, cationic counter-ions from the chloride salt also have observable effects on the dissolution rate. For example, additions of potassium chloride bring a notable increase in etch rate compared to hydrochloric acid while additions of sodium chloride actually lead to a diminished etch rate [

31,

32]. The role of cations in the chloride salt which leads to this effect is not usually explained in primary literature concerning chemical machining of copper but has been mentioned as likely a result of chloride transference in the electrolyte solution [

24]. In the absence of applied voltage, it is still meaningful to discuss ion migration by local electric fields under mixed-potential theory [

43,

44]. However, the attribution to transference is not obvious.

The transference number, tj, has the physical interpretation of the fraction of current carried by ion j in a dilute solution of uniform concentration [

45],

where

z is charge,

u is mobility, and

c is concentration. When concentration gradients exist, accounts must be made for diffusion in addition to ion migration [

45]. Subtlety arrives with the understanding that mobility is defined using the hydrodynamic radius under Stokes’ law, which includes the coordination sphere, rather than the ionic radius [

46],

where

ze is charge in Coulombs,

f is the Stokes’ law value for the friction coefficient, η is the coefficient of viscosity, and

a is the hydrodynamic radius. Therefore, for small ions, such as the alkali earth metals, mobility trends inversely with ionic radius due to lesser hydration as shielding increases down the group, (

Table 1) [

46]. Attribution of the relative effects of potassium and sodium to chloride transference may still be plausible, however, considering other effects on transference which may supersede differences in mobility, such as stronger ion pairing with sodium. In any case, explicitly elucidating the factors underlying these observations would prove invaluable to the design of improved chemical machining etchants.

Relative to hydrochloric acid, potassium ions are far less mobile and thereby allow greater transference by chloride. An increase in the etch rate would then be expected to follow the addition of potassium, as passivity is rate-determining and limited by chloride transport [

21,

24,

28]. Indeed, in acidic chloride solutions with potassium, the dissolution rate of solid copper increases with greater [K

+]:[H

+] ratio [

24]. Considering this accelerating effect, industrial chemical machining systems may then benefit by exchanging some portion of hydrochloric acid for potassium chloride as a chloride source. Some acid would still be necessary to maintain low pH for stability, which is explained in a later section. A multi-step chemical machining process has been described recently which utilizes this effect by interrupting the application of ferric chloride etchant to wash the copper surface with potassium chloride for some time before returning to ferric chloride to complete the machining process [

31]. Results confirmed a reduction of necessary residence time of the copper workpiece in ferric chloride etchant in addition to an 80% reduction in lateral etching using KCl rather than HCl, improving anisotropy.

Another recent study introduced ammonium chloride into acidic copper chloride baths with hydrochloric acid and found a significant enhancement on reaction rate again with anisotropic preference for etching in the vertical direction [

17]. The observation was attributed to copper complexation following decomposition of ammonium to ammonia, but significant activity by ammonia under the experimental conditions of pH 1.0 and 50°C seems unlikely. The pK

a of ammonium is 8.5387 at 50°C [

47]. The Henderson-Hasselbach equation (without correction for high ionic strength) [

48], Equation (3), then gives only 2.9×10

-6 % of ammonium present as ammonia at equilibrium under these conditions.

In any case, the accelerating effect of ammonium in acidic cupric chloride etchant is notable and should be a topic of further research, perhaps by examining its effect on chloride transference.

3. Metal Ion Stability

The essential function of complexing agents in fending passivity extends more generally to stabilize dissolved metals in etchant baths, as their absence leads to challenges of solubility. The high ionic strength characteristic of industrial etchants also brings high viscosity, as strong, intermolecular interactions with greater ionic character increase the activation energy associated with molecular migration [

46]. Considering the diffusion control imposed by passivity, further increasement in viscosity by concentration of ionic solutes may then slow reaction rates by hindering ion mobility with greater viscous drag against the coordination sphere by the Stokes-Einstein relation [

46]. In fact, it is common practice to add water to industrial etchant baths to account for evaporation during chemical machining at elevated temperatures [

27]. This practice is permissible for the acidic chloride etchants but is not advisable for alkaline cupric ammine chloride, as explained within this section.

Copper(I) disproportionation is highly favored in water, Reaction (4), with its equilibrium constant on the order of 10

6 [

49].

Complexing agents are therefore necessary to stabilize copper(I), since the absence of such ligands from the coordination sphere would allow a great extent of disproportionation to solid copper precipitates in addition to a greater probability of hydrolysis brought by increased hydration [

50],

or, to show the hydrated metal in the presence of hydroxide more generally [

51],

Among other factors, thermodynamic stability of coordination complexes is generally correlated with greater electron donation from ligands to the metal center [

52]. The relative effects of ligands in stabilizing a complex may be inferred from the spectrochemical series, Equation (7), which ranks ligands by the extent of d-orbital splitting imparted, the ligand field stabilization energy [

53]. Donor atoms in ambidentate ligands are underlined.

It should be noted that the spectrochemical series suggests hydrated copper or iron would be better stabilized than their chloride complexes. However, formation constants for chloride complexes of the oxidized and reduced form of either metal are generally favorable, ranging within orders of 10

0–10

5 [

41,

54,

55,

56,

57]. A limitation is thus exemplified of applying ligand field theory alone to infer stability. Also necessary are thermodynamic considerations, such as the greater ionic character of coordination covalent bonds to chloride, with greater coulombic attraction between higher valencies of the harder acids, Cu

2+ and Fe

3+ [

58], as well as the entropic driving force of water molecules displaced from the inner coordination sphere forming hydrogen bonds to the aqueous solvent matrix.

Implications of hydrolysis on the overall stability of metal ion complexes in the context of each of the three case etchants are discussed within this section.

3.1. Alkaline Cupric Ammine Chloride

Concentration of ammonium salts increases copper(II) solubility at decreasing pH irrespective of the anion being either chloride or sulfate, thereby showing ammonia to be the primary species in maintaining copper(II) solubility [

38]. Indeed, the addition of chloride had no effect on the solubility of the ion in either salt at concentrations ranging 1–2 M [

38]. However, this does not exclude the possibility that chloride may instead promote the solubility of the copper(I) oxidation state, which is shown in this section to be more impactful to the overall stability of dissolved copper in alkaline ammine etchant. This also seems plausible since copper(I) is better stabilized by chloride than copper(II), as given by its greater stability constants at various ionic strengths [

40] and being a more polarizable, softer acid for the borderline ligand [

58]. Further research seeking improvements to chemical machining by alkaline cupric ammine should then consider investigating a similar experimental design [

38] which instead measures the solubility of both ions.

As with passivity, the stability of dissolved copper ions of alkaline ammine etchant is complicated by the competing complexing agents present: ammonia, chloride, and water. Different cuprous complexes are then formed as relative concentrations vary. Low ratios of ammonia-to-copper favor solid cuprous chloride precipitate in addition to passive surface film [

19]; and further depletion of the ratio of copper to either ammonia or chloride would be expected to bring significant solubility challenges by increasing the prevalence of copper hydrates, which are highly susceptible to disproportionation and hydrolysis in alkaline environments, Reaction (6) [

19,

49,

59,

60,

61].

Depending on concentration, copper(II) begins to hydrolyze above pH 4 and precipitates cupric oxide or hydroxide with further increasement. However, the hydrolysis of copper(I) is not easily measured on account of its disproportionation to precipitate solid copper [

49]. Low solubility is likewise observed of cuprous oxide formed especially at high pH, Reactions (8–9) [

49].

Reaction (7) indicates cuprous oxide also forms from solid copper with large equilibrium constants even in water. It then follows that the instability of hydrated copper ions is heightened in alkaline medium by strong thermodynamic favor of solid copper precipitates of copper(I) disproportionation to induce the formation of cuprous oxide by reaction with copper(II), effectively precipitating dissolved copper(II) as well and limiting its quantity which can remain in solution [

49].

Avoiding hydrolysis and maintaining the stability of solvated copper ions, particularly copper(I), is therefore imperative, as failure may lead to catastrophic failure of the etchant bath by a great extent of precipitation, a condition known industrially [

62] as “sludging” or a “sludge-out”. Despite its severity, this condition is not well reported in chemical machining literature. The slurry is likely a mixture of solid copper, cuprous chloride, and the oxides and hydroxides of both copper(I) and copper(II) by the mechanisms of disproportionation and hydrolysis described. Practical additions of water to alkaline cupric ammine etchant then brings risk of precipitation, as its localized concentration risks replacing ligands from the inner coordination sphere of dissolved copper with greater hydration, thereby promoting hydrolysis.

3.2. Ferric Chloride

The acidic chloride etchants have the benefit of much greater stability, since the acidic environment disfavors the forward reaction of Equilibrium (5–6) [

63,

64]. Although, hydrolysis of iron ions may still proceed. Hydrolysis of iron(III) in water occurs much more readily than that of iron(II), beginning near pH 1 by the formation of FeOH

2+ [

63,

65]. Chemical machining literature has reported reactions describing the formation of ferric trihydroxide from either ferric trichloride or monochloride [

27,

63], but the trihydroxide yields in much lesser quantities than the other hydroxides, with an upper limit of -12 determined for its log(

Keq) [

65]. This species is instead more prevalent in neutral and basic solutions [

65]. Rather, in acidic solutions, dinuclear Fe

2(OH)

24+ and mononuclear Fe(OH)

2+ and Fe(OH)

2+ are observed [

65]. In contrast, the hydrolysis of iron(II) is very slight, as precipitation of the hydroxide occurs even before hydrolysis proceeds to a significant extent [

65]. Such soluble ferrous products are not observed significantly until pH neutral or above.

Despite the advantage of an acidic environment, this low barrier to precipitation necessitates attention to the maintenance of hydrochloric acid to disfavor precipitation. Evidenced industrially, “sludge” is often observed in chemical machining applications of ferric chloride as free acid concentrations diminish, which leads to mechanical issues arising from the precipitate slurry such as clogged nozzles of pressurized sprays [

27,

63]. Water additions may then be tolerated so long as pH is not altered significantly. On the extreme end, rinsing of the workpiece in water after chemical machining by ferric chloride would quickly hydrate dissolved metal ions and lead to extensive precipitation of oxides and hydroxides directly on the material surface which may be difficult to remove, thereby necessitating dilute hydrochloric acid in the rinse to promote solubility [

63]. Having both copper and iron dissolved in the etchant volume, the hydrolytic stability of acidic copper chlorides also concerns the use of ferric chloride etchant [

63].

3.3. Acidic Cupric Chloride

Acidic copper(II) chloride earned early recognition as the simpler system for chemical machining of copper by having copper as the only metal present and chloride from hydrochloric acid the only anion [

64]. Noted previously, copper(II) hydrolysis begins near pH 4, and the presence of acid generally shifts equilibrium in favor of the soluble metal ions [

49]. Thus, no sludge is formed usually [

64], and etchant stability is not problematic so long as acid concentration is maintained below this relatively high limit. Water additions and post-machining rinsing of the workpiece would then be expected to be, at the least, more tolerable than for ferric chloride.

Research regarding acidic cupric chloride etchant may instead direct attention toward increasing its stable dissolved copper capacity. Both acidic chloride etchants usually exhibit a lesser capacity for dissolved copper than alkaline ammine chloride [

13], likely on account of the greater stability noted of copper ammine complexes. Although, solubility is also essential in considering new chemical machining agents. For example, the spectrochemical series, Equation (7), suggests fluoride may be a suitable ligand to offer greater stabilization energy than chloride for dissolved copper [

53]. Fluoride is, in fact, a strong-field ligand relative to chloride, but copper(II) fluoride is still an ineffective etchant. The salt is only sparingly soluble and exhibits a slower etch rate than acidic copper(II) chloride [

66]. In contrast, copper(II) bromide is soluble and dissolves solid copper at faster rates than the fluoride salt [

66], but the machining product, copper(I) bromide, struggles with solubility [

67]. Additionally, the anion Br

– is unable to dissolve the passive CuBr film which generates at the copper surface [

68], as may be predicted for the weak-field ligand.