Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The Mediterranean sea urchins Paracentrotus lividus and Arbacia lixula are ecologically coexisting grazers that exert strong control on benthic algal communities but display strikingly different physiological and ecological traits. To explore the biochemical basis of these differences, we applied high-resolution magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (HR-MAS NMR) spectroscopy combined with multivariate chemometric analysis to characterize the gonadal metabolomes of both species. Distinct species-specific metabolic fingerprints were observed. A. lixula exhibited an osmolyte- and redox-oriented profile dominated by betaine, taurine, sarcosine, TMA, TMAO, carnitine, and creatine, reflecting enhanced homeostatic regulation, antioxidant protection, and mitochondrial flexibility. In contrast, P. lividus showed an amino-acid- and lipid-enriched anabolic metabolism characterized by high levels of lysine, glycine, glutamine, and proline, consistent with a reproductive strategy focused on energy storage and protein biosynthesis. Additional metabolites—including malonate, methylmalonate, uridine, xanthine, formaldehyde, methanol, and 3-carboxypropyl-trimethyl-ammonium—highlighted microbial mediation of methylated substrates and host–microbiota metabolic interactions. These results reveal two complementary adaptive strategies: a resilience-oriented osmolyte metabolism in A. lixula and an efficiency-oriented anabolic metabolism in P. lividus. The findings demonstrate that metabolomic divergence, coupled with distinct microbial associations, underpins the ecological and physiological differentiation of these sympatric echinoids. HR-MAS NMR metabolomics thus provides a powerful tool for elucidating adaptive biochemical pathways in marine invertebrate holobionts.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design and Procedure

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Tissue Preparation

2.3. Chemicals

2.4. HR-MAS NMR Spectroscopy

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

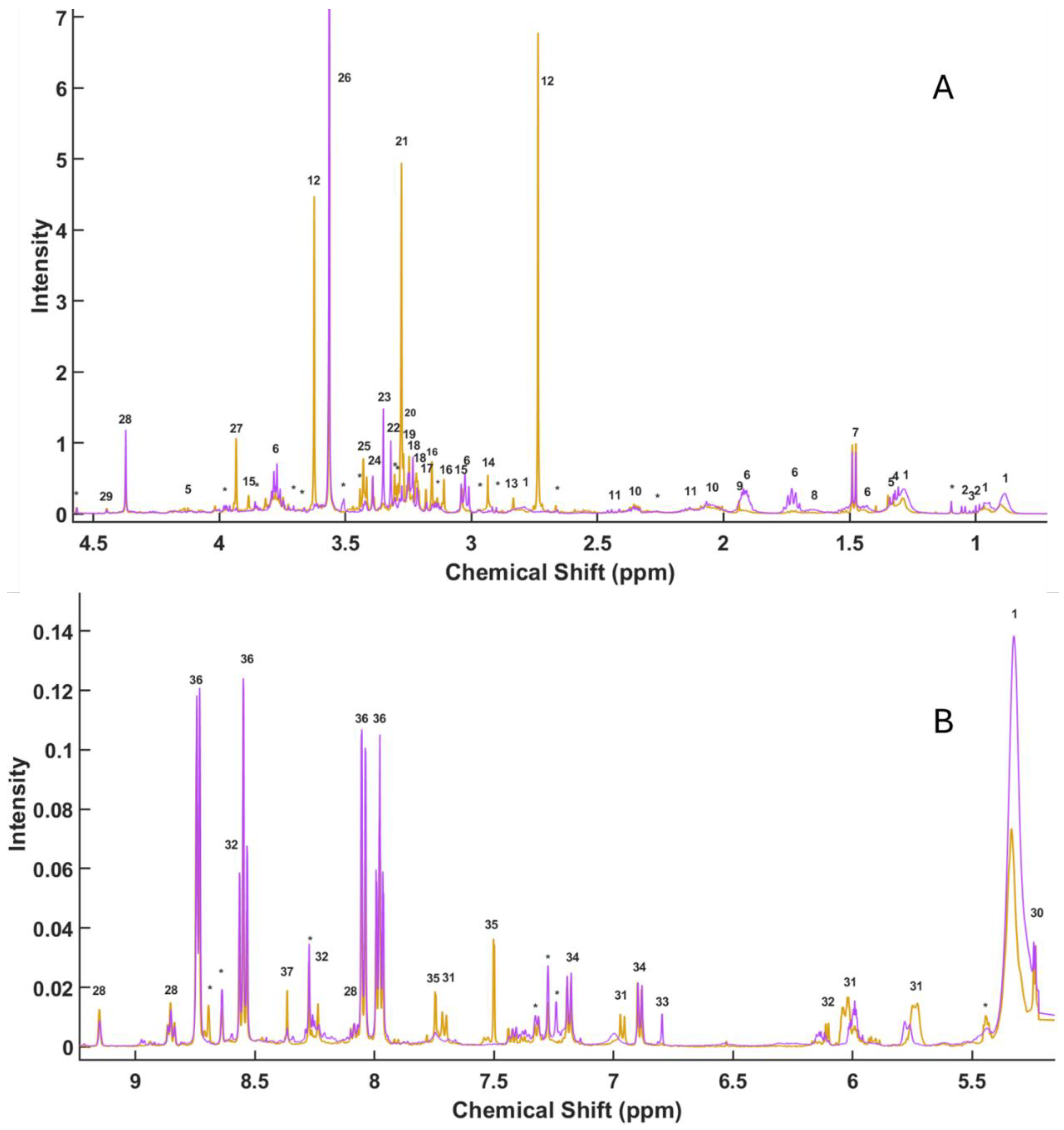

3.1. HR-MAS Spectral Analysis

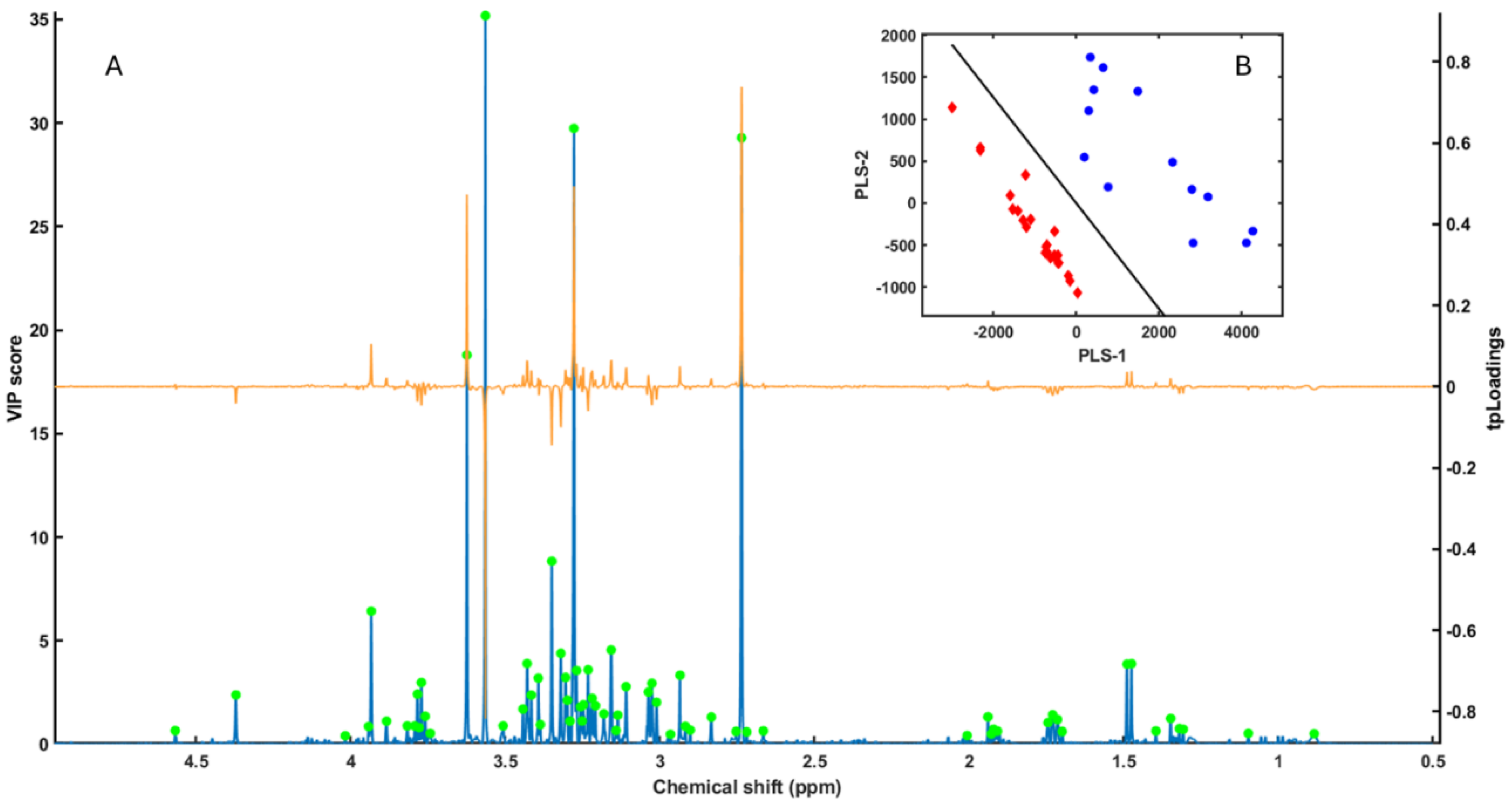

3.2. PLS-LDA Model

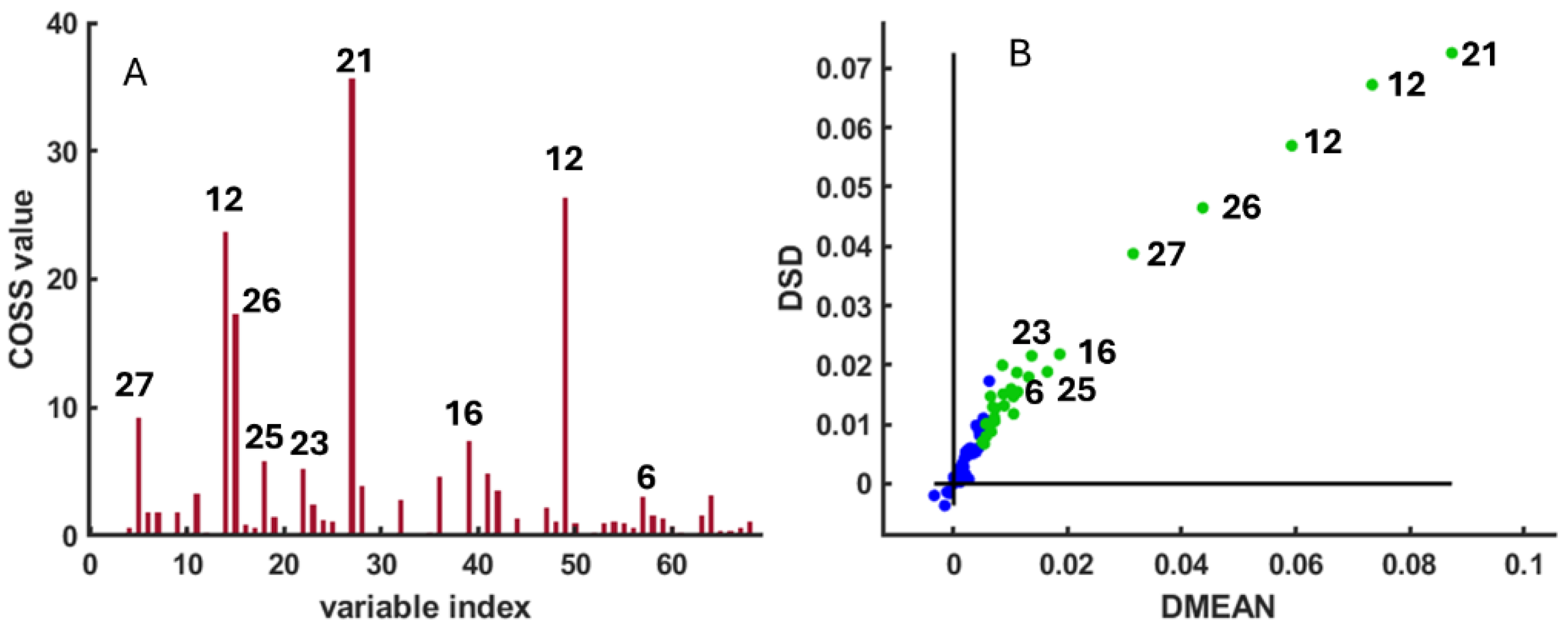

3.3. SPA Variable Selection

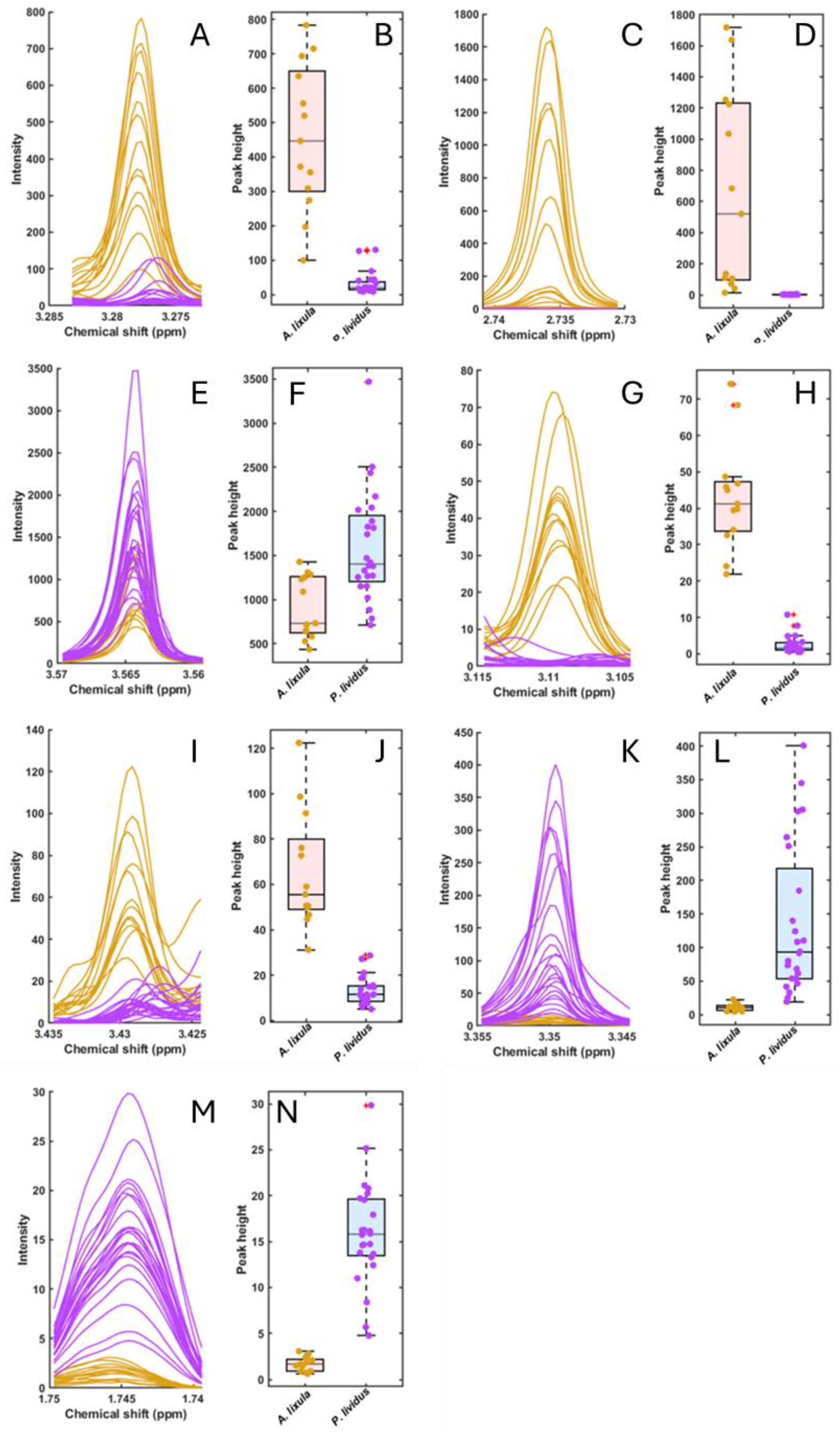

3.4. Selected Metabolites and Boxplots

4. Discussion

4.1. Core Metabolic Contrasts

4.2. Secondary Metabolites and Microbial Mediation

4.3. Integrative Ecological and Evolutionary Context

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonaviri, C. and et al. "Leading role of the sea urchin arbacia lixula in maintaining the barren state in southwestern mediterranean." Marine Biology 158 (2011): 2485–93. [CrossRef]

- Wangensteen, O. S., X. Turon, A. García-Cisneros, M. Recasens, J. Romero and C. Palacín. "A wolf in sheep’s clothing: Carnivory in dominant sea urchins in the mediterranean." Marine Ecology Progress Series 441 (2011): 117-28.

- Rocha, F., A. C. Rocha, L. F. Baião, J. Gadelha, C. Camacho, M. L. Carvalho, F. Arenas, A. Oliveira, M. R. G. Maia and A. R. Cabrita. "Seasonal effect in nutritional quality and safety of the wild sea urchin paracentrotus lividus harvested in the european atlantic shores." Food Chemistry 282 (2019): 84-94.

- Montero-Torreiro, M. F. and P. Garcia-Martinez. "Seasonal changes in the biochemical composition of body components of the sea urchin, paracentrotus lividus, in lorbé (galicia, north-western spain)." Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 83 (2003): 575-81. [CrossRef]

- Arafa, S., M. Chouaibi, S. Sadok and A. El Abed. "The influence of season on the gonad index and biochemical composition of the sea urchin paracentrotus lividus from the golf of tunis." The Scientific World Journal 2012 (2012): 815935.

- Ouréns, R., L. Fernández and J. Freire. "Geographic, population, and seasonal patterns in the reproductive parameters of the sea urchin paracentrotus lividus." Marine Biology 158 (2011): 793-804.

- Foo, S. A., M. Munari, M. C. Gambi and M. Byrne. "Acclimation to low ph does not affect the thermal tolerance of arbacia lixula progeny." Biology Letters 18 (2022): 20220087. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Vilert, R., V. Arranz, M. Martín-Huete, J. C. Hernández, S. González-Delgado and R. Pérez-Portela. "Effect of ocean acidification on the oxygen consumption of the sea urchins paracentrotus lividus (lamarck, 1816) and arbacia lixula (linnaeus, 1758) living in co2 natural gradients." Frontiers in Marine Science 12 (2025): 1500646.

- Gianguzza, P., G. Visconti, F. Gianguzza, S. Vizzini, G. Sarà and S. Dupont. "Temperature modulates the response of the thermophilous sea urchin arbacia lixula early life stages to co2-driven acidification." Marine environmental research 93 (2014): 70-77.

- Pérez-Portela, R. and C. Leiva. "Sex-specific transcriptomic differences in the immune cells of a key atlantic-mediterranean sea urchin." Frontiers in Marine Science 9 (2022): 908387. [CrossRef]

- Luparello, C., D. Ragona, D. M. L. Asaro, V. Lazzara, F. Affranchi, V. Arizza and M. Vazzana. "Cell-free coelomic fluid extracts of the sea urchin arbacia lixula impair mitochondrial potential and cell cycle distribution and stimulate reactive oxygen species production and autophagic activity in triple-negative mda-mb231 breast cancer cells." Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 8 (2020): 261.

- Bundy, J. G., M. P. Davey and M. R. Viant. "Environmental metabolomics: A critical review and future perspectives." Metabolomics 5 (2009): 3-21.

- Bayona, L. M., N. J. de Voogd and Y. H. Choi. "Metabolomics on the study of marine organisms." Metabolomics 18 (2022): 17.

- Beckonert, O., M. Coen, H. C. Keun, Y. Wang, T. M. D. Ebbels, E. Holmes, J. C. Lindon and J. K. Nicholson. "High-resolution magic-angle-spinning nmr spectroscopy for metabolic profiling of intact tissues." Nature protocols 5 (2010): 1019-32.

- Villa, P., D. Castejon, M. Herraiz and A. Herrera. "H-1-hrmas nmr study of cold smoked atlantic salmon (salmo salar) treated with e-beam." Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 51 (2013): 350-57. [CrossRef]

- Castejón, D., P. Villa, M. M. Calvo, G. Santa-María, M. Herraiz and A. Herrera. "1h-hrmas nmr study of smoked atlantic salmon (salmo salar)." Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 48 (2010): 693-703. [CrossRef]

- Aru, V. "Application of nmr-based metabolomics techniques to biological systems: A case study on bivalves." (2016):.

- Lardon, I., M. Eyckmans, T. Vu, K. Laukens, G. De Boeck and R. Dommisse. "H-1-nmr study of the metabolome of a moderately hypoxia-tolerant fish, the common carp (cyprinus carpio)." Metabolomics 9 (2013): 1216-27. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Y. Liang, Q. Xu and D. Cao. "Key wavelengths screening using competitive adaptive reweighted sampling method for multivariate calibration." Anal Chim Acta 648 (2009): 77-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q., H.-D. Li, Q.-S. Xu and Y.-Z. Liang. "Noise incorporated subwindow permutation analysis for informative gene selection using support vector machines." Analyst 136 (2011): 1456-63.

- Yun, Y. H., F. Liang, B. C. Deng, G. B. Lai, C. M. V. Goncalves, H. M. Lu, J. Yan, X. Huang, L. Z. Yi and Y. Z. Liang. "Informative metabolites identification by variable importance analysis based on random variable combination." Metabolomics 11 (2015): 1539-51. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000363040600006. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I., I. Standal, D. Axelson, B. Finstad and M. Aursand. "Identification of the farm origin of salmon by fatty acid and hr c-13 nmr profiling." Food Chemistry 116 (2009): 766-73. [CrossRef]

- Lindon, J., J. Nicholson and E. Holmes. "Hr-mas nmr spectroscopy for metabolomics and lipidomics: Applications in fisheries science." Molecules 26 (2021): 931. [CrossRef]

- Heude, C., E. Lemasson, K. Elbayed and M. Piotto. "Rapid assessment of fish freshness and quality by h-1 hr-mas nmr spectroscopy." Food Analytical Methods 8 (2015): 907-15. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000351289400011. [CrossRef]

- Huxtable, R. J. "Physiological actions of taurine." Physiological Reviews 72 (1992): 101–63.

- Podbielski, I., L. Schmittmann, T. Sanders and F. Melzner. "Acclimation of marine invertebrate osmolyte systems to low salinity: A systematic review & meta-analysis." Frontiers in Marine Science 9 (2022): 934378.

- Yancey, P. H. "Organic osmolytes as compatible, metabolic and counteracting cytoprotectants in high osmolarity and other stresses." Journal of Experimental Biology 208 (2005): 2819-30. [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, T. and M. B. Hjelte. "The amino acid metabolism of the developing sea urchin egg." Experimental Cell Research 2 (1951): 474–91.

- Martínez-Pita, I., F. J. García and M.-L. Pita. "The effect of seasonality on gonad fatty acids of the sea urchins paracentrotus lividus and arbacia lixula (echinodermata: Echinoidea)." Journal of Shellfish Research 29 (2010): 517-25.

- Benevenga, N. J. and K. P. Blemings. "Unique aspects of lysine nutrition and metabolism." The Journal of Nutrition 137 (2007): 1610S–15S. [CrossRef]

- Benatti, C., V. Rivi, S. Alboni, A. Grilli, S. Castellano, L. Pani, N. Brunello, J. M. C. Blom, S. Bicciato and F. Tascedda. "Identification and characterization of the kynurenine pathway in the pond snail lymnaea stagnalis." Scientific Reports 12 (2022): 15617.

- Huang, Z., J. J. Aweya, C. Zhu, N. T. Tran, Y. Hong, S. Li, D. Yao and Y. Zhang. "Modulation of crustacean innate immune response by amino acids and their metabolites: Inferences from other species." Frontiers in Immunology 11 (2020): 574721. [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, L., A. Debnath, S. Jamshed, J. V. Wish, J. C. Raine, G. T. Tomy, P. J. Thomas and A. C. Holloway. "An emerging cross-species marker for organismal health: Tryptophan-kynurenine pathway." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (2022): 6300.

- Wang, Y., Y. Zhang, W. Wang, X. Dong and Y. Liu. "Diverse physiological roles of kynurenine pathway metabolites: Updated implications for health and disease." Metabolites 15 (2025): 210.

- Feng, Y., B. F. Bowden and V. Kapoor. "Screening marine natural products for selective inhibitors of key kynurenine pathway enzymes." Redox Report 5 (2000): 95–97.

- Sun, J., M. A. Mausz, Y. Chen and S. J. Giovannoni. "Microbial trimethylamine metabolism in marine environments." Environmental Microbiology 21 (2019): 513-20. [CrossRef]

- Mootapally, C., P. Sharma, S. Dash, M. Kumar, S. Sharma, R. Kothari and N. Nathani. "Microbial drivers of biogeochemical cycles in deep sediments of the kathiawar peninsula gulfs of india." Science of The Total Environment 965 (2025): 178609. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969725002438. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. S. "Malonate metabolism: Biochemistry, molecular biology, physiology, and industrial application." Journal of biochemistry and molecular biology 35 (2002): 443-51. [CrossRef]

- Forny, P., X. Bonilla, D. Lamparter, W. Shao, T. Plessl, C. Frei, A. Bingisser, S. Goetze, A. van Drogen and K. Harshman. "Integrated multi-omics reveals anaplerotic rewiring in methylmalonyl-coa mutase deficiency." Nature metabolism 5 (2023): 80-95.

- Torres, J. P., Z. Lin, J. M. Winter, P. J. Krug and E. W. Schmidt. "Animal biosynthesis of complex polyketides in a photosynthetic partnership." Nature Communications 11 (2020): 2882.

- Lee, M.-C., J. C. Park and J.-S. Lee. "Effects of environmental stressors on lipid metabolism in aquatic invertebrates." Aquatic toxicology 200 (2018): 83-92. [CrossRef]

- Ghonimy, A., L. S. L. Greco, J. Li and N. M. Wade. "An hypothesis on crustacean pigmentation metabolism: L-carnitine and nuclear hormone receptors as limiting factors." Crustaceana 96 (2023): 939-56.

- Ellington, W. R. "Evolution and physiological roles of phosphagen systems." Annual review of physiology 63 (2001): 289-325.

- Haider, F., H. I. Falfushynska, S. Timm and I. M. Sokolova. "Effects of hypoxia and reoxygenation on intermediary metabolite homeostasis of marine bivalves mytilus edulis and crassostrea gigas." Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 242 (2020): 110657. [CrossRef]

- Berg, G. M. and N. O. G. Jørgensen. "Purine and pyrimidine metabolism by estuarine bacteria." Aquatic Microbial Ecology 42 (2006): 215-26.

- Zhou, Z., G. C. Zhuang, S. H. Mao, J. Liu, X. J. Li, Q. Liu, G. D. Song, H. H. Zhang, Z. Chen and A. Montgomery. "Methanol concentrations and biological methanol consumption in the northwest pacific ocean." Geophysical Research Letters 50 (2023): e2022GL101605.

- Anthony, C. "The biochemistry of methylotrophic micro-organisms." Science Progress (1933-) (1975): 167-206.

- Esposito, R., S. Federico, F. Glaviano, E. Somma, V. Zupo and M. Costantini. "Bioactive compounds from marine sponges and algae: Effects on cancer cell metabolome and chemical structures." International journal of molecular sciences 23 (2022): 10680. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z., J. Wei, Y. Hu, D. Pi, M. Jiang and T. Lang. "Caffeine synthesis and its mechanism and application by microbial degradation, a review." Foods 12 (2023): 2721.

- Rocha, F., H. Peres, P. Diogo, R. Ozório and L. M. P. Valente. "The effect of sex, season and gametogenic cycle on gonad yield, biochemical composition and quality traits of paracentrotus lividus along the north atlantic coast of portugal." PeerJ 7 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Pinna, S., A. Pais, P. Campus, N. Sechi and G. Ceccherelli. "Habitat preferences of the sea urchin paracentrotus lividus." Marine Ecology Progress Series 445 (2012): 173-80.

- Gianguzza, P. and et al. "Climate change and the expansion of arbacia lixula in the mediterranean: A potential shift in ecosystem balance." Global Change Biology 26 (2020): 3902–15.

- Arranz, V., L. Schmütsch-Molina, R. Fernandez Vilert, J. C. Hernández and R. Pérez-Portela. "Sea urchin holobionts: Microbiome variation across species, compartments and locations in paracentrotus lividus and arbacia lixula." Frontiers in Marine Science 12 (2025): 1615711. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barreras, R., A. Dominicci-Maura, E. L. Tosado-Rodríguez and F. Godoy-Vitorino. "The epibiotic microbiota of wild caribbean sea urchin spines is species specific." Microorganisms 11 (2023): 391.

- Baldassarre, L., H. Ying, A. Reitzel and S. Fraune. "Microbiota mediated plasticity promotes thermal adaptation in nematostella vectensis." bioRxiv (2021): 2021-10. [CrossRef]

- Lessios, H. A., S. Lockhart, R. Collin, G. Sotil, P. Sanchez-Jerez, K. S. Zigler, A. F. Perez, M. J. Garrido, L. B. Geyer and G. Bernardi. "Phylogeography and bindin evolution in arbacia, a sea urchin genus with an unusual distribution." Molecular Ecology 21 (2012): 130-44.

- De Giorgi, C., C. Lanave, M. D. Musci and C. Saccone. "Mitochondrial dna in the sea urchin arbacia lixula: Evolutionary inferences from nucleotide sequence analysis." Molecular biology and evolution 8 (1991): 515-29. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Vilert, R. and et al. "Physiological response of paracentrotus lividus and arbacia lixula to ocean acidification: Implications for future mediterranean ecosystems." Marine Environmental Research 187 (2025): 106995.

| Peak | δ (ppm) | Compound | Multiplicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.8846 | F.A | m |

| 1 | 0.9657 | F.A. | m |

| 2 | 0.9851 | Valine | d |

| 3 | 1.0101 | Isoleucine | d |

| 2 | 1.0416 | Valine | d |

| * | 1.0962 | Unassigned | s |

| 1 | 1.284 | F.A. | m |

| 4 | 1.3074 | Treonine | d |

| 5 | 1.3262 | Lactate | d |

| 6 | 1.4307 | Lysine | m |

| 7 | 1.4754 | Alanine | d |

| 8 | 1.6562 | Arginine | m |

| 6 | 1.7288 | Lysine | m |

| 6 | 1.9209 | Lysine | m |

| 9 | 1.9389 | Acetate | s |

| 10 | 2.068 | Glutamate | m |

| 11 | 2.1344 | Glutamine | m |

| * | 2.2653 | Unassigned | m |

| 10 | 2.3573 | Glutamate | m |

| 11 | 2.4446 | Glutamine | m |

| * | 2.6954 | Unassigned | s |

| 12 | 2.7357 | Sarcosine | s |

| 1 | 2.7893 | F.A. | m |

| 13 | 2.8333 | TMA | s |

| * | 2.9338 | Unassigned | d |

| 14 | 2.9349 | N-Methylhydantion | s |

| * | 2.9741 | Unassigned | d |

| 6 | 3.0258 | Lysine | t |

| 15 | 3.0375 | Creatine | s |

| 16 | 3.1094 | Malonate | s |

| * | 3.1351 | Unassigned | d |

| 16 | 3.1556 | Malonate | s |

| 17 | 3.1571 | Methylmalonate | s |

| 18 | 3.2183 | Choline | s |

| 18 | 3.2326 | Choline | s |

| 19 | 3.2385 | Carnitine | s |

| 19 | 3.2476 | Carnitine | s |

| 20 | 3.2696 | TMAO | s |

| 21 | 3.2781 | Betaine | s |

| * | 3.3037 | Unassigned | s |

| * | 3.3048 | Unassigned | s |

| 22 | 3.3202 | 3-carboxypropyl-trimethyl-amonium | s |

| 23 | 3.35 | Formaldehyde | s |

| 24 | 3.3918 | Methanol | s |

| 25 | 3.4292 | Taurine | t |

| * | 3.44 | Unassigned | s |

| * | 3.50763 | Unassigned | s |

| 26 | 3.56447 | Glycine | s |

| 12 | 3.6242 | Sarcosine | s |

| * | 3.6242 | Unassigned | s |

| * | 3.662 | Unassigned | s |

| 6 | 3.7717 | Lysine/Alanine | m |

| * | 3.8589 | Unassigned | m |

| 15 | 3.8846 | Creatine | s |

| 27 | 3.9341 | Betaine | s |

| * | 3.9741 | Unassigned | m |

| 5 | 4.1255 | Lactate | q |

| 28 | 4.3716 | Trignelline | s |

| 29 | 4.446 | Inosine | s |

| 30 | 5.2421 | Glucose | d |

| 1 | 5.3261 | F.A. | s |

| * | 5.4335 | Unassigned | m |

| 31 | 5.7291 | Uridine | m |

| 31 | 6.0202 | Uridine | m |

| 32 | 6.1005 | IMP | d |

| 33 | 6.7965 | Timol | s |

| 34 | 6.8985 | Tyrosine | d |

| 31 | 6.9718 | Uridine | d |

| 34 | 7.1783 | Tyrosine | d |

| * | 7.2399 | Unassigned | s |

| * | 7.2751 | Unassigned | s |

| * | 7.3286 | Unassigned | d |

| 35 | 7.5021 | Xantine | s |

| 31 | 7.6993 | Uridine | d |

| 35 | 7.7477 | Xantine | s |

| 36 | 7.978 | Kinurenine | t |

| 36 | 8.0532 | Kinurenine | d |

| 28 | 8.088 | Trigonelline | t |

| 32 | 8.2373 | IMP | s |

| * | 8.2736 | Unassigned | s |

| 37 | 8.3667 | Adenosine | s |

| 36 | 8.5501 | Kinurenine | t |

| 32 | 8.6014 | IMP | s |

| * | 8.6381 | Unassigned | s |

| * | 8.6953 | Unassigned | s |

| 36 | 8.7312 | Kinurenine | d |

| 28 | 8.8508 | Trigonelline | t |

| 28 | 9.1522 | Trigonelline | s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).