1. Introduction: The Ageing of the European Population and Its Social Impact

According to the last available statistics (EUROSTAT, 2025), on 1 January 2024 there were 449 million people living in the European Union (EU)

1. During the last 20-year period 2004-2024, the total population of the EU increased from 432.8 million to 449.2 million, a growth of 4%. However, this increase should be differentiated by age group: in fact, over the same period, the share of persons aged 65 and over increased in all EU countries of 5.2 percentage points, from 16.4% to 21.6%; and the proportion of persons aged 80 and over grew in all EU countries by 2.3%, from 3.8% to 6.1%. On the contrary, over the same period the proportion of children and young adolescents (under the age of 15) declined in the EU by 1.6%, dropping from 16.2% to 14.6%; and the share of young people (under the age of 19) decreased in all EU countries by 2.4%, from 22.4% to 20%.

What the above statistics say is that over the last two decades Europe has become an ageing society: a further indicator of this process is the median age of the population, which increased by 5.4 years from 39.3 years in 2004 to 44.7 years in 2024, 43.1 years for men and 46.3 years for women, the feminization of aging. A first reason of this sex difference is that the increasing life expectancy is not not sexually equal: women live on average 5.3 years longer than men. In fact, in 2023 the EU life expectancy at birth for women was 84.0 and only 78.7 for men. Compared with the situation 20 years earlier, the gender gap in life expectancy at birth was 6.4 years in the EU in 2003 (women 80.8 and men 74.4), 1.1 years more than in 2023.

In more general terms, life expectancy at birth rose rapidly during the last century in Europe due to several factors, from reductions in infant mortality to rising living standards, from improved lifestyles and better education to advances in healthcare and medicine (McKewon, 1976). In 2023, the life expectancy at birth in the EU was estimated at 81.4 years as a result of an increase of 3.7 years between 2003 and 2023. Following the outbreak of the COVID-19, pandemic life expectancy fell to 80.4 years in 2020 and further to 80.1 years in 2021; but it rebounded to 80.6 years in 2022 and to 81.4 years in 2023.

Furthermore, live births decreased significantly: in 2023, the crude birth rate in the EU stood at 8.2 live births per 1000 persons. Comparing 2023 with 2003, there was a decrease in all EU countries except Bulgaria. The crude death rate (the number of deaths per 1000 persons) was 10.8 in 2023 in the EU, while in 2003 was 10.1 and fluctuated between 9.7 and 10.5 until 2019. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it rose to 11.6 in 2020, reached a peak of 11.9 in 2021 and since then it slightly decreased to 10.8 in 2023. This means that there were more deaths than births since 2012: the EU’s crude rate of natural population change (difference between live births and deaths) was −2.6 in 2023. Looking back, in 2003, the crude rate of natural population change was 0.0 followed by positive rates until 2012, when it turned negative. Since 2016 it decreased continuously to reach −1.1 in 2019. With the COVID-19 pandemic, it dropped to −2.5 in 2020, −2.7 in 2021 and −2.9 in 2022. In 2023 it slightly increased to −2.6.

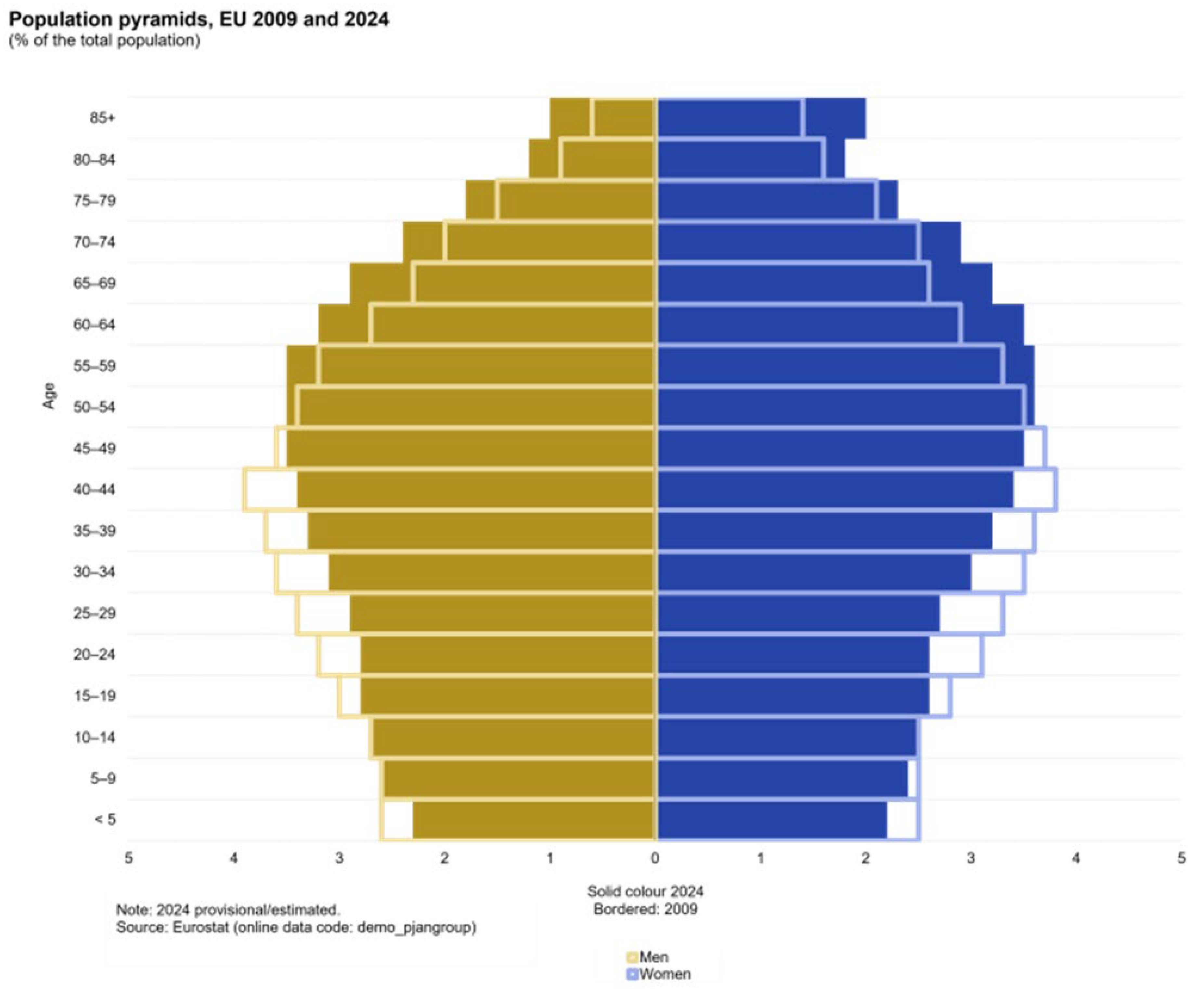

The above-described situation of Europe as an ageing society can be summarised by a population pyramid (

Figure 1) that shows the number of people sorted by age group comparing the situation in 2024 to 2009. As it is evident, the oldest age groups on top show a significant increase especially of women (on the right) compared with men (on the left side); while the youngest age groups at the bottom show an equally significant decrease during the fifteen years period.

This changing demographic landscape means that during the first quarter of the twenty-first century the countries of the European Union have been characterized by an advanced state of population ageing, which risks threatening the two fundamental pillars of these post-industrial societies: an extensive welfare state and a liberal-democratic institutional framework.

In the first case, what is at stake is the very sustainability of welfare state because of the growing intergenerational divide existing in Europe, which has become increasingly evident since the 2008 economic crisis (Hüttl et al. 2015). Indeed, the fact that more recently born cohorts are steadily becoming less numerous than cohorts born earlier means that there is a growing group of elderly people who are dependent on pensions and are eligible for many other welfare state programs (health care, social services, social transports, etc.) means that the system could not be maintained in the medium to long term. On the other side, “across Europe, the economic consequences of the 2008 financial crisis—rising unemployment and stagnating wages combined with inflating asset prices and significantly reduced public spending—have impacted heavily on younger people (Cribb et al., 2017; European Commission, 2017)” (Wildman et al., 2022: 2285). In fact, the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis created serious challenges for Europe’s young people, particularly vulnerable to the effects of a weaker economy: the effects of a weaker economy: “unaffordable housing and rising living costs bite hardest on groups that lack savings or assets to cushion them through tough times, while unemployment and labour market precariousness are especially pressing concerns for young people looking for a way into job markets for the first time” (Shaw, 2019: 6). Conversely, older people have been, on average, better protected, partly due to their position in the life course outside the labour force and the positive performance of housing values for those who own their homes, and partly also thanks to political decisions to direct governments’ economic austerity measures towards working-age subsidies and family benefits while protecting the rights of the older people (e.g., the state pension) (Tucker, 2017).

In the period 2002–2017, in most EU countries a larger share of total social protection spending was directed towards supporting the elderly population than towards the non-elderly population. This bias in favour of older people in social protection spending has strengthened over time: despite the subsequent introduction of some expansionary measures during the COVID 19 pandemic, the welfare state was unable to compensate market income losses for the population of working age.

However, in the EU countries “the decomposition of overall income inequality showed that just a small proportion of it can be attributed to differences between age groups (i.e., between people of different age), as more than 95% of overall inequality is related to inequality within age groups (i.e., between people of similar age)” (Reitano et al., 2021: 11). This implies that the intersection of ageing and social class (likely combined with other variables such as gender and ethnicity) over the life course quite significantly affects who is most at risk of poverty in retirement. Despite this, explanations of social differences in terms of intergenerational conflict have become fashionable, with the older generations standing accused of hoarding resources and stealing the future of younger generations (Shaw, 2018). “Baby boomers versus millennials” seems to be the new rhetoric used by some interest groups and political parties to mask the deepening inequalities between those who have wealth (mostly older generations, but not only) and those who do not. And the conflict between the interest of younger and older generation is exploited as a rationale not only to cut welfare state provisions but even to question the legitimacy of EU countries’ second pillar: their liberal-democratic institutional framework.

2. Questioning the Intergenerational Social Contract?

Relationships between generations have always been problematic in every society: there is a sort of ‘structural contradictions’ between the older generations’ expectations of being supported by the younger generations, and the latter’s fear that the same level of support will be unavailable in their own old age (Prinzen, 2014: 434). The sort of ‘intergenerational social contract’ which stays among the foundations of European liberal democracies is based on a consensus on an intergenerational pact for the fair distribution of resources between generations via taxation and public social expenditures (Walker, 1996). More specifically, “intergenerational redistribution of resources through taxation and spending is part of a social contract that depends for its legitimacy on the principles of reciprocity (mutual support between generations), equity (relation between inputs and outputs for one generation) and equality (corresponding conditions for different generations)” (Wildman et al., 2022: 2285). If these three fundamental principles of reciprocity, equity and equality between generations fail, this means that the liberal-democratic institutional framework itself is at risk.

The reciprocity principle is mainly at the basis of an informal intergenerational contract embedded in family relations and support across generations (Arber and Attias-Donfut (2000). The underlying logic is that parent invest in their children by supporting them in their life choices, hoping that this will ensure their old age and the continuity of the family, as well as the informal contract itself.

The types of resource transfers across generations within family can be categorised into three main dimensions: financial (assets, property, capital), instrumental (physical support, personal care, childcare), and emotional (companionship, advice, listening, feeling closeness) (Wong et al., 2020: 9). In this way, family is a pillar even of contemporary welfare states, since it remains a critical mechanism against insecurity, risk and life crisis even in most EU countries. However, a series of demographic, social and cultural changes are seriously threatening the survival of the reciprocity principle within families in EU countries. Demographic factors are mainly linked to the loss of the traditional multigenerational extended family structure, which was the foundation of the social well-being especially in Euro-Mediterranean countries, due to nuclearization of families, rising divorce rates, and step-family formation, which significantly reduce and segment the size and relationships of families. The main social factor is due to migration, which forcibly separates families for work or other reasons (political, ecological, etc.). The cultural factor is mainly related to the weakening of the children’s filial piety towards their parents and the individualization of the lives of even the older baby boomers generation. Of course, this factor can vary depending on the various ethnic groups and their more or less deeply rooted norms in this regard.

All these factors are making it increasingly difficult for both the older and the younger generations in need to obtain support from their family. According to the most recent scoping review on these topics (Wong et al., 2020), there is no comparative studies on EU countries, but only national studies or, to the utmost, studies comparing some countries in Europe and elsewhere. It would be interesting to assess to what extent the three series of factors mentioned above have radically or only partially changed the implementation of the principle of reciprocity within families in the different macro-regions of Europe

2, enquiring and comparing the strength and the direction of resource transfer in each of them. As Wong and colleagues (2020: 1) suggest, “downward transfers from senior to junior generations occur more frequently than upward transfers in many developed countries. Women dominate instrumental transfers, perhaps influenced by traditional gender roles”. In any case, patterns of resource transfer between generations within families can be significantly different in each European macro-region according to its historical, social, cultural and demographic context. In addition to downward and upward transfers, a concurrent, bidirectional transfer pattern across generations is also possible: which is more probable for the adult generations of higher educational level and small social networks (Wong et al., 2020: 11).

According to the few studies available comparing some European countries, compared to Northern regions, Southern regions have lower proportions of grandparents caring for grandchildren (Hank and Buber, 2009; Igel and Szydlik, 2011). Moreover, in Northern Europe help between parents and children is very common, but typically little time-consuming; the contrary is true for Southern Europe, where comparably few support relations are very intense in terms of time. Central Western Europe lies in-between with average transfer rates and intensities (Brandt, 2013). The empirical findings based on the SHARE (Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe) data explain this apparent contradiction by supporting the “specialization hypothesis”: a higher national level of social services coincides with less intensive help and more demanding care; well-developed welfare states thus lower the risk of an overburdening of the family and secure the overall support of older people and young families through efficient collaboration between family and state (Igel et al., 2009).

However, intergenerational care is more prevalent in Southern and Central European countries, where children are legally obligated to support parents in need, and care is perceived as a responsibility of the family; whereas in Northern Europe, the wider availability of formal care services enable adult children, particularly daughters, to have more choice about their activities and use of time (Haberkern and Szydlik, 2010). On the other hand, the likelihood of a downward money transfer being made is the outcome of an intricate resolution of the resources (ability) of the parents and the needs of a child: suggesting that, at least with reference to cross-generational money transfers, no consistent differences by welfare state regime were found (Schenk et al., 2010).

In sum, “the complicated interplay of ethno-cultural background, culture norms, social welfare systems, and economic situation must be recognised. The role of family members in intergenerational transfers varies across cultures” (Wong et al., 2020:17): only further studies based on more extensive data will be able to better explore this rather complicated plot.

The other two principles of equity and equality of intergenerational resource transfer are mostly related to social policy and welfare systems. They represent the foundation of the formal intergenerational contract which legitimate the welfare state and the liberal-democratic institutional framework insofar they are based on a just distribution of resources and a reciprocal support between generations defined in social policies by addressing the needs and risks individuals may face across different stages of the life course. The idea of an intergenerational contract is a metaphor based on Rousseau’s concept of social contract: which “does not need to be formally stated, but the terms must still be recognised, and they must be the same for everyone so that it is nobody’s interest to make the conditions of the contract unfavourable for others” (Zechner and Sihto, 2024: 711). The idea of the social contract is connected to the emergence of welfare states during the 20th century, even though its origins dates back to Hobbes (Boucher and Kelly, 1994). It offers a justification for the utilization of the public power of government to control and steer the lives of citizens: “the state and especially the welfare state, governs the moral aspects by accommodating individual and group interests for the sake of equity (Sulkunen, 2007). The concept of social contract is thus used to address the questions of how welfare states can secure legitimate redistribution of resources across generations” (Zechner and Sihto, 2024: 711).

According to the systematic literature review conducted by these two Finnish scholars, there are nine main components that can be identifies as parts of both informal (family-based) and formal (welfare-based) intergenerational contracts, which assume somewhat different characteristics in the two cases (Zechner and Sihto, 2024: 716-719). The first one concerns whether it is implicit or explicit: in the informal contract, it is implicitly intertwined in the social practices of individual and families, while in the formal contract it is explicitly codified in legislative norms and in the structures and policies of the welfare state. If the boundaries between the two are blurring due to some turmoil, it means that both need to be renegotiated. The second component concerns the parties involved: in the case of informal contract, these are usually clearly defined to include at least three family generations of (grand)children, parents and grandparents; while in formal contract the central party is the welfare state, which establishes an ideal contract with the three unknown generations of the young, people of the working age, and the older persons. Where the key group in sustaining the generational contract is the adult working generation, since social risks most likely occur at the beginning and end of the life course. The third component concerns responsibilities related to the duties allocated to different generations: in the informal contract, these are part of the implicit rules on mutual roles with their rights and obligations. The adult generation is supposed to work, have children and take care of the older generation: in this way, they ‘repay’ the care received from their parents during childhood and are expected to receive the same care from their children once they reach old age. The formal contract is based on taxes and contributions paid by the working generation to the state, which will use them to fund educational services for their children and health care and social services for all of them. Once retired, the older generation is expected to receive a state pension based on their contributions but paid for by contributions from their children who have also become working adults.

The fourth component relates to the distributional nature of the intergenerational contract, which concerns what is distributed in terms of material and social goods, to whom and why. In the case of informal contract, assets (housing, money and properties) and caregiving are usually exchanged between older parents and their adult children within the family. The formal contract, on the other hand, is based on the distribution of monetary subsidies (pensions, assistance, unemployment benefits, etc.) or social services (education, health care, welfare services) financed by taxes and contributions from working generations. Another fundamental component of intergenerational contract is time, since it is temporally organised between at least two generations. In this case, “both formal and informal generational contracts are future oriented, and the contracts are made between past, present and future generations” (Zechner and Sihto, 2024: 718). However, there is an intrinsic intertemporal asymmetry in the contract, due to the lack of guarantees that future generations will reciprocate, or the risk they will do so differently from that hoped for by the older generations. This risk can cause friction between generations, both in the case of informal contract—parents are unsure whether the money and care invested in their children will be reciprocated once they reach old age—and in the case of formal contract—government policies can change, economies can suffer a recession, social legislation can shift. Furthermore, the interconnection between formal and informal contracts is evident in the ability of social policies to shape and modify, through various incentives and restrictions, the norms related to child and older adults care, education, retirement, inheritance, and marriage.

The sixth component is implementation, that is, how the intergenerational contract is put into practice. In this case, while informal contracts are implemented through inheritance of houses and properties, cash transfers, and caregiving based on the symbolic and binding power of family ties, formal contracts implementation relies on the legal power of the welfare state and its social policies and redistributive systems. The seventh component is the value base underlying both types of contracts: shared moral values and mutual trust are essential to their social legitimacy. This moral value base oriented towards collectivism, altruism, fairness, solidarity and justice is necessary in order to establish social relationships of trust, reciprocity and interdependency between generations: “In each society, there is a need to balance between solidarity towards other groups of people and their needs, and egoism in the form of focusing on one’s own needs and wellbeing” (Zechner and Sihto, 2024: 719).

Lastly, the eighth and ninth components of intergenerational contract are the potential risks and uncertainties that could jeopardize it and the consequent need for its maintenance as a requirement for its continued existence (Johnson, 1995). In particular, when the two principles of equity and equality of intergenerational resource transfer are called into question, it means there is a lack of shared values or a conflict of values that can jeopardize the contract itself. Especially in the case of the formal intergenerational social contract, this situation could lead to a questioning of the distribution of resources to older generations. The individualisation of values among younger generations, negative attitudes towards older persons, a lack of commitment among younger generations, and potential age conflicts between younger and older generations are all real risks which must be avoided through serious and ongoing work to maintain the legal norms and regulations that support the welfare state and the social and cultural environment in which they are historically embedded.

Current debates taking place among European policy makers, the media and scholars are exactly focusing on these issues: in particular, the starting point is the “widespread pessimism around young people’s prospects and evidence of a fracturing social contract, with little faith in the principles of intergenerational equity, equality and reciprocity upon which welfare states depend” (Wildman et al., 2022: 2284). The consequences of the economic and financial crisis that began in 2008, in terms of rising unemployment and stagnant wages combined with rising property prices and a significant reduction in public spending, have had a heavy impact on Europe’s younger generations, while older ones have been more protected. In particular, the principle of equity is challenged by the widespread perception among younger generations that wealth and income are not fairly distributed in the EU due to the growing divide between old and young people: a gap further increased by public spending shifted away from education, families and children towards pensioners (Hüttl et al., 2015). Moreover, the principle of equality is questioned by the common belief that the same level of income, wealth and benefits enjoyed by older generations today will not be available to younger generations in the foreseeable future. Clearly, these two issues risk undermining intergenerational social cohesion and support for the welfare state’s formal social contract: however, to what extent is this way of framing the problems a true picture of the situation or a “toxic solution” to intergenerational inequity and inequality that views welfare state redistribution as the problem (Christopher, 2018: 111)? Furthermore, is there a real conflict between the interest of younger and older generations regarding welfare state spending, or is there something else behind this apparent conflict?

As regard the first question, the risk of adopting what has been termed as “generationalism” (Purhonen, 2016: 102) as a distorted and exaggerated view of the problem of intergenerational inequity has already been highlighted by White (2013), who considers simplistic the narrative that characterises older people as a privileged homogeneous group, ignoring their growing diversity in terms of gender, class, ethnic group and place of residence. Moreover, “generation” is notoriously an imprecise theoretical concept, lacking the empirical foundation enjoyed by family lineage at the micro-social level and age-group or cohort at the meso level. The three elements classically considered by Mannheim (1952) as constitutive of a generation at the macro social level—shared temporal, historical and socio-cultural location—are very general and subject to interpretation. Generation is a “discursive construct” (Scherger, 2012) arising from the actions and consciousness of people sharing the three above elements during certain periods (Timonen and Conlon, 2015).

As regard the second question, the moral language of “generationalism” in reality “instigates artificial confrontation between the ‘generations’”, and “has become a master narrative for reshaping the welfare state. By breaking down society into generations, welfare state reformers can construct a demographic imperative that assumes that welfare spending is a burden placed by the old on the young” (Wildman et al., 2022: 2287). Besides failing to consider multiple contributions older people make to society through paid work, volunteering, informal care, child care, and so on, this flawed narrative is contradicted by the findings of some surveys in European countries, which show that the young people do not blame the older generations for intergenerational inequity, but rather a remote state incapable of responding to social needs and failing to spend sufficiently across all generations (Wildman et al. 2022: 2296). There is no evidence of intergenerational conflict in European countries, even though some tension is reported to exist because of pessimism and fears surrounding the future prospects of younger generations (Ayalon, 2019). This tension produces an intergenerational ambivalence that characterises relationships within families, with a mixture of a sense of maintaining kin solidarity and frustration and resentment due to a lack of confidence in the belief that each generation will be better off than the previous one (Park, 2014).

A comparative study (Shaw, 2019) conducted by the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) in six European countries (Denmark, France, Germany, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom) has shown that, although there is a growing sense of concern about the economic prospects of the younger generation in most European nations, framing this as an issue of “intergenerational fairness”, implying a tension between generations, is incorrect: “two assumptions are often implicit: first, that there is a conflict between the interests of different generations and, second, that this conflict will necessarily erupt into political action. The evidence reported here suggest that these assumptions may be flawed. The case studies show that there is not a simple relationship between economic challenges, however serious, and political reactions. It is not the case that the political conversation about intergenerational fairness is always loudest where the economic challenges for young people are greatest” (Shaw, 2019: 21). Therefore, the results of this survey suggest that young people are more pessimistic than angry; although they are concerned about the future of their generation, so-called “Millennials” generally do not blame older people for the situation and do not subscribe to the idea of a generation war.

3. From Intergenerational Fairness to Active Ageing

Although there is currently no intergeneration war in European countries, the problem of intergeneration inequity remains real due to the tensions and ambivalence which pose a serious threat to both the formal and informal intergenerational contracts. This menace happens in a context of shift from a post-war Keynesian welfare state to an individualist neoliberal risk society based on the private accumulation of capital (Christophers, 2018). A change of scenario that has led to a substantial return from social sharing to individualization of risks, with the progressive retrenchment of the welfare state: which implies that intergenerational inequalities once again reflect life chances based on family assets and inherited wealth (Resolution Foundation, 2018).

It is in this climate that the concept of “intergenerational fairness”, adopted in the USA since the 1980s, has rapidly taken hold even in Europe, especially after the 2008 crisis. However, its meaning is not unique: “the notion of intergenerational fairness is a flexible concept that can also be used as a justification for further austerity, the withdrawal of entitlements and the dismantling of welfare states” (Shaw, 2019: 3). This means that, in this variant of neoliberal austerity policy, ‘fairness’ becomes simply a matter of rationing too small a share of welfare state resources among competing generations (Shaw, 2018): it is already clear that this redistribution along age lines risks exacerbating inequalities within generations (Woodward and Wyn, 2015) and fomenting a form of political struggle that pushes generations against each other (Christophers, 2018).

An alternative conception of intergenerational fairness could start from the concept of ambivalence used to depict the mix of conflict and solidarity that characterizes intergenerational relationships in contemporary post-industrial societies. On one side, the bonds of solidarity between generations do not seem to be in question: “shared norms around the deservingness of support of vulnerable older people and inter-family cohesion and affection tend to positive views of older generations” (Wildman et al. 2022: 2296-2297). On the other side, self-interest and perceptions of injustice among younger generations tend to express negative views generated by frustrated expectations and repressed anger. At the origin of this ambivalence, it is suggested there is “a symptom of a shift in established social structures, resulting in reality running counter to expectations” (Hillcoat-Nallétamby and Phillips, 2011): ambivalence is therefore the result of complex relational experiences that exist within a larger network of interdependent social relationships. Experiences of frustrated expectations of achieving full independence from their parents by young adults; but also experiences of their parents’ frustrated expectations regarding the future of their children and the awareness that the old pattern of family wealth and network relationships has once again become the main determining factor in life chances.

This is the main reason why a different approach to intergenerational inequality cannot ignore variables such as social class, gender, ethnicity and marital status: otherwise, it risks becoming a ‘smokescreen’ that distracts from social inequality by masking the role of intersecting identities (Holman and Walker, 2021). Achieving this goal requires a lifelong approach that examines the role of all the above-mentioned variables as enablers or barriers throughout people’s life course: “while not replacing or minimising social class, gender or ethnicity as a determinant of advantage, generations provide an additional social category for the analysis of inequalities” (Wildman et al. 2022: 2297). It is therefore necessary to move from an exclusive focus on intergenerational fairness to ageing as a lifelong process and the result of the intersection of all the above variables in post-industrial societies (Dumas and Turner, 2009).

The life course perspective focuses on ageing as a multidimensional process that unfolds throughout a person’s life: “ageing well” is the desired outcome of this process shared by the different generations. However, this outcome is differently interpreted according to various approaches: “the most prevalent terms employed over recent decades have been successful ageing in the United States and active ageing in Europe” (Foster and Walker, 2014: 84). Both approaches stem from the same scientific theory of activity, which emerged in the early 1960s as an antithesis of disengagement theory (Cumming and Henry, 1961), which considered ageing as a ‘natural’ and inevitable process of gradual detachment from society as people grow older. Disengagement theory was a functionalist view of old age considered as a distinct stage of life, and part of a normative idea of life course. Diametrically opposed, activity theory (Havighurst, 1963) maintains that that normal ageing involves preserving, for as long as possible, the attitudes and activities of middle age.

Even though they are sometimes considered interchangeably, successful and active ageing involve very different perspectives. Successful ageing (Butler, 1974; Rowe and Kahn, 1987) has contributed to overcome the widely held idea that aging is inevitably linked to disease and an inevitable series of losses. On the contrary, the three fundamental pillars of this approach are “low probability of disease and disease-related disability, high cognitive and physical functional capacity, and active engagement with life” (Foster and Walker, 2021:3). This positive narrative of ageing emphasizes self-responsibility in ageing and rejects conventional expectation of failure in later life. However, as Foster and Walker (2021: 3-4) point out, it is not without criticism.

Firstly, it prioritizes physical and mental abilities over social and behavioural aspects, aiming for successful ageing according to criteria often unattainable for many older adults. Especially the oldest-old who do not meet these strict criteria still demonstrate considerable levels of well-being and cannot be labelled as unsuccessful due to disabilities or health problems. Secondly and consequently, since successful ageing is essentially about how older individuals should age, not how people themselves age successfully, there is a risk of oversimplification, which reduce successful ageing to an exclusionary and even discriminatory perspective. Thirdly, successful ageing is considered an individualistic concept that fails to account for the interdependence between agency and structure, changes in peoples’ lives and their social structural position, assuming that through individual choices and commitment people can automatically age successfully and remain physically and socially active. By failing to recognize the impact of structural factors (both as facilitators or barriers) across the life course, this perspective could reinforce attempts to limit state responsibility for welfare interventions to address social and structural inequalities, in line with neoliberal assumption of exclusive personal autonomy and responsibility. Finally, focusing primarily on old age, this approach performs a static assessment of an individual’s successful ageing, without considering a life course perspective, developmental processes and trajectories of continuity and change over time.

Active ageing is an alternative perspective developed since the 1990s that seeks to overcome all these limitations. It is based on the most comprehensive definition of “active ageing” proposed by WHO (2002: 12) as “the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age”. It implies a conception of “active” not simply referring to physical and cognitive abilities, but to ongoing participation in social, economic, cultural, spiritual and civic affairs. This implies a vision emphasizing autonomy and participation in old age rather than dependence and passivity not only in economic terms, stressing productivity and performance, but in a more holistic perspective including social activities and relationships. Furthermore, this approach rejects an exclusive emphasis on ‘youthful’ physical activities, “an overflow of mid-life values” (Tornstam, 1992: 322) which could be discriminatory for many older people affected by chronic diseases and/or disabilities, “but promotes the notion of being active as involving living by one’s own rules rather than those ‘normalized’ by others” (Foster and Walker (2021: 4)).

Thirdly, the risk that even active ageing could become a coercive strategy is clear to the promoters of this strategy, contributing “to the exclusion of the oldest-old, and those most vulnerable and dependent, who fail to meet inappropriate active ageing criteria” (Foster and Walker (2021:4). For this reason, they highlight the necessity of older people’s close involvement in defining what “active ageing” means in their lives and in the “active citizenship” for the co-production of the policies regarding them (Del Barrio et al., 2018). Otherwise, if active ageing is operationalised in a way that emphasizes only personal responsibility, similarly to successful ageing, “it actually functions as a mere alibi for dismantling the welfare state and shifting risks and costs to the single individual” (Pfaller and Schweda, 2019:47). The elimination of structural barriers related to age or dependency remains a fundamental duty of the welfare state if especially vulnerable groups—those suffering from severe physical, mental, sensory limitations or social marginality—are not to be excluded from ageing actively and active ageing is not reduced to “little more than empty rhetoric” (Clark and Warren, 2007). However, if this non-exclusionary strategy could be adequately pursued, it would have to avoid the classic paternalistic and standardized model applied in most industrialized countries: and to do so, it would have to be based on the principle of the primacy of agency (Boudiny, 2013: 1090-1093)). The principle of agency recognizes a person’s ability to make her/his own choices and act accordingly even when affected by illness or disability: this means that alternative ways of actively ageing can be conceived and pursued by different people depending on their subjectivity. A person-centred policy strategy of active ageing should be based on her involvement in the decision-making process and on supporting her freedom of choice: “the aim is to achieve a partnership in which the two destructive extremes are avoided, i.e., expert-based decision-making without reference to older adults’ perspectives versus simply leaving older persons to express what they want in an unsupported way” (Boudiny, 2013: 1092).

Finally, a comprehensive active ageing strategy involves a life course perspective that recognizes that a person’s path to old age is not predetermined but depends primarily on earlier life experiences and their influence: the ageing process affects people of all ages, not just the elderly. Recognizing this dynamic nature of ageing means acknowledging that life courses powerfully shape the ageing process. And the central focus of life courses, if we question the static notion of ‘natural stages of life’ (Kohli, 1986), are lifestyles.

4. A Framework for the Analysis of Ageing Styles from a Life Course Perspective

During the twentieth century, a person’s life course has been socially structured on the basis of three fundamental stages: “learning-youth, work-adulthood and retirement aging” (del Barrio et al., 2018: 1). This normative life course was functional to the general organization of industrial society during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which required a preliminary period of education before starting to work, and a final period of retirement due to disengagement after work and age-based pension provision, unlike previous peasant society in which these two life stages did not exist. This standardized structure of the life course has become so deeply ingrained in the general organization of society that it appears ‘natural’. However, because of the profound demographic, social, economic and cultural transformations of post-industrial societies, this ageing framework of the last century can no longer be applied. A more fluid interpretation of the life course has emerged, rather than one based on deterministic ‘stages’: education can last throughout one’s life span as lifelong learning; and the boundary between work and retirement have become increasingly blurred. As a result, a de-institutionalization and de-standardization of the life course (Kohli, 1986) has taken place, with a changing social perception of the nature and timing of middle and later life as well as the meaning of age itself; since “lives have become less orderly and predictable and more flexible and individualized” (Barrett and Barbee, 2022: 1).

One the one hand, this trend toward the “subjectivization” of ageing has raised the suspicion that this greater fluidity conceals a new life structure shaped by neoliberalism, which emphasizes individual performance, productivity, responsibility, and expected success throughout the life span and in all contexts: this worry should be taken into account given the growing inequalities in life course experiences and contexts in older age, in conjunction with the fact that individual diversity tends to increase with age.

On the other hand, the “subjectivization” of ageing has fostered the need to better understand the subjective dimension of the life course by integrating life course sociology with the gerontological perspective on subjective ageing ((Barrett and Barbee, 2022: 2). Indeed, life course sociology has mostly focused on the socio-historical timing and biographical unfolding of lives by a macro-social approach, highlighting their patterning as an objective phenomenon in terms of timing, sequencing, pacing of events, and transitions, with little attention to the subjective dimension. However, all the five principles on which this perspective is based (Shanahan et al., 2016) imply subjective components of the life course. The first principle of life span development considers ageing as a lifelong process shaped by experiences throughout life: and in addition to chains of risk or protective contextual factors such as family, education or social class that accumulate over time to produce cumulative advantages or disadvantages, there are also subjective factors to consider such as images of life stages, awareness of ageing, awareness of age-related changes, age identity, and self-perception of ageing. The second principle highlights the importance of historical time (macrosocial events) and place of residence in shaping individuals’ lives: however, individuals “mental maps” of the places they live, and their significant life course events are also important subjective factors to consider in this regard. The third principle of timing emphasizes that the consequences of events and transitions vary depending on when they occur in the life course: here too, subjective factors such as the perceived ideal timing and sequencing of transitions, the perceived ideal duration in role statuses, and the perceived boundaries of life stages, can play a meaningful role. The fourth principle of “linked lives” highlights the interdependence of the life paths of social network members suggesting that “each generation is bound to fateful decisions and events in the other’s life course” (Elder, 1985: 40). This also means that the perceived temporal contours of our own lives are shaped by those of important others, including our relatives, neighbours and friends. Finally, the fifth principle of agency indicates that people are active agents who make decisions about their lives within the structural opportunities and constraints of history and social contexts (Hitlin and Long, 2009; Hitlin and Johnson, 2015): and behind these decisions, there are age stereotypes and ageist attitudes, perceived longevity, age salience or consciousness, imagined futures, and other subjective dimensions.

Therefore, if the objective dimensions of the life course are the result of the conditioning power of the social structure, the subjective dimensions are instead the expression of people’s agency power. The interplay between the objective and subjective life course, between structure and agency is at the origin of lifestyles (Cockerham, 2005). The concept of lifestyle has been discussed in classical sociological theory, starting with Max Weber (1978): whose vision already considered the two major components of lifestyles as the life choices (agency) and life chances (the structural probability of realizing one’s choices). Weber’s contribution to lifestyle theory is therefore fundamental and very current: particularly his view “of the dialectical interplay of choice and chance in lifestyle determination”, so that “it can be said that individuals have a range of freedom, yet not complete freedom, in choosing a lifestyle, that is they have the freedom to choose within the social constraints that apply to their situation in life” (Cockerham, 2017: 1).

Among other sociologists who have contributed to lifestyle theory, Giddens’ concept of duality of structure is useful for understanding the role played by social structure in enhancing or limiting lifestyle choice by connecting the individual with the pattern of behaviour shared with the other people in the reference group (Giddens, 1991). Bourdieu’s concept of habitus (Bourdieu, 1994) also constitutes another relevant contribution to lifestyle theory, as it indicates the repertoire of dispositions to act that guides behavioural choices. This framework of attitudes is the results of both the socialization process in the social context of belonging and of life experience of the subject: “the habitus produces enduring dispositions toward a lifestyle that becomes routine and, when acted out regularly over time, reproduces itself” (Cockerham, 2017: 2-3).

More recently, Willian Cockerham (2005; 2017) has formulated the “health lifestyle theory”, which considers four categories of structural variables as the main causal factors determining lifestyles (Cockerham, 2017:3): 1) class circumstances; 2) age, gender and race/ethnicity; 3) collectivities (social networks); and 4) living conditions (quality of housing, access to basic utilities, neighbourhood facilities, etc.). These four variables provide the social context for socialization process and life experience, which in turn influence life choices (agency); at the same time, the four structural factors define life chances both in terms of opportunities and barriers. In Cockerham’s model, life choices within the range of available life chances interact to produce the habitus, the mindset of dispositions to act leading to practices (actions) of different types (alcohol use, smoking, dietary habits, exercise, etc.) related to health. Health lifestyles are the result of this causal chain culminating in more or less healthy practices: and they can reproduce or change the habitus through the feedback they transmit to it. Therefore, Cockerham’s definition of health lifestyle is “collective patterns of health-related behavior based on choices from options available to people according to their life chances” (2005: 55).

While there is a growing body of research examining health lifestyles among children, adolescents and young adults, few studies have been conducted on late middle aged and older adults. One of the few is the research conducted by Cockerham and colleagues (2020) on the health lifestyles of US adults entering late middle age, with the aims of assessing the structural predictors of belonging to different lifestyles and exploring their relationships with previously diagnosed chronic conditions and current physical health status. On the basis of the analysis of data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY-79 50+ Health Module) conducted by the US Bureau of Statistics, the results confirmed a robust relationship between structural variables, and in particular class (socioeconomic status, SES), gender, race/ethnicity and health lifestyles, that prior studies had observed; and “uncover an association between health lifestyles and health status due to the onset of serious illness that seems to impact on health behaviours” (Cockerham et al. 2020:4 0). This transition of late middle-aged adults with serious illnesses to healthier lifestyles, while the health lifestyles of younger adults are generally “locked-in” by late life, suggests that “health lifestyles are dynamic throughout the life course as the factors motivating one’s health lifestyle change. When considered alongside the robust associations between SES and lifestyles that we found, this finding presents an interesting question: Does SES determine who is able to successfully change lifestyles?” (Cockerham et al. 2020: 43).

The answer of Cockerham and colleagues is that probably such structural variables as “educational attainment and the human capital it provides play important roles in the lives of those who are able to change” (Cockerham et al. 2020:43): while this is undoubtedly true, it is equally clear that these scholars have doubts about a total determination of lifestyles by structural variables. And these doubts are furtherly reinforced by the other results showing that “most respondent lifestyles were not completely one or the other. Both healthy and unhealthy behavioral practices were mixed in the same lifestyle class as well as varying between classes” (Cockerham et al. 2020: 45). These results furtherly show that the evolution of health lifestyles over the life course is strongly conditioned but not totally determined by structural variables: which means there is more room for human agency as an expression of subjectivity influenced by biological (genetic heritage, physical characteristics, etc.) and psychological variables (self-efficacy, locus of control, mastery, planful competence, expectations, aspirations, etc.).

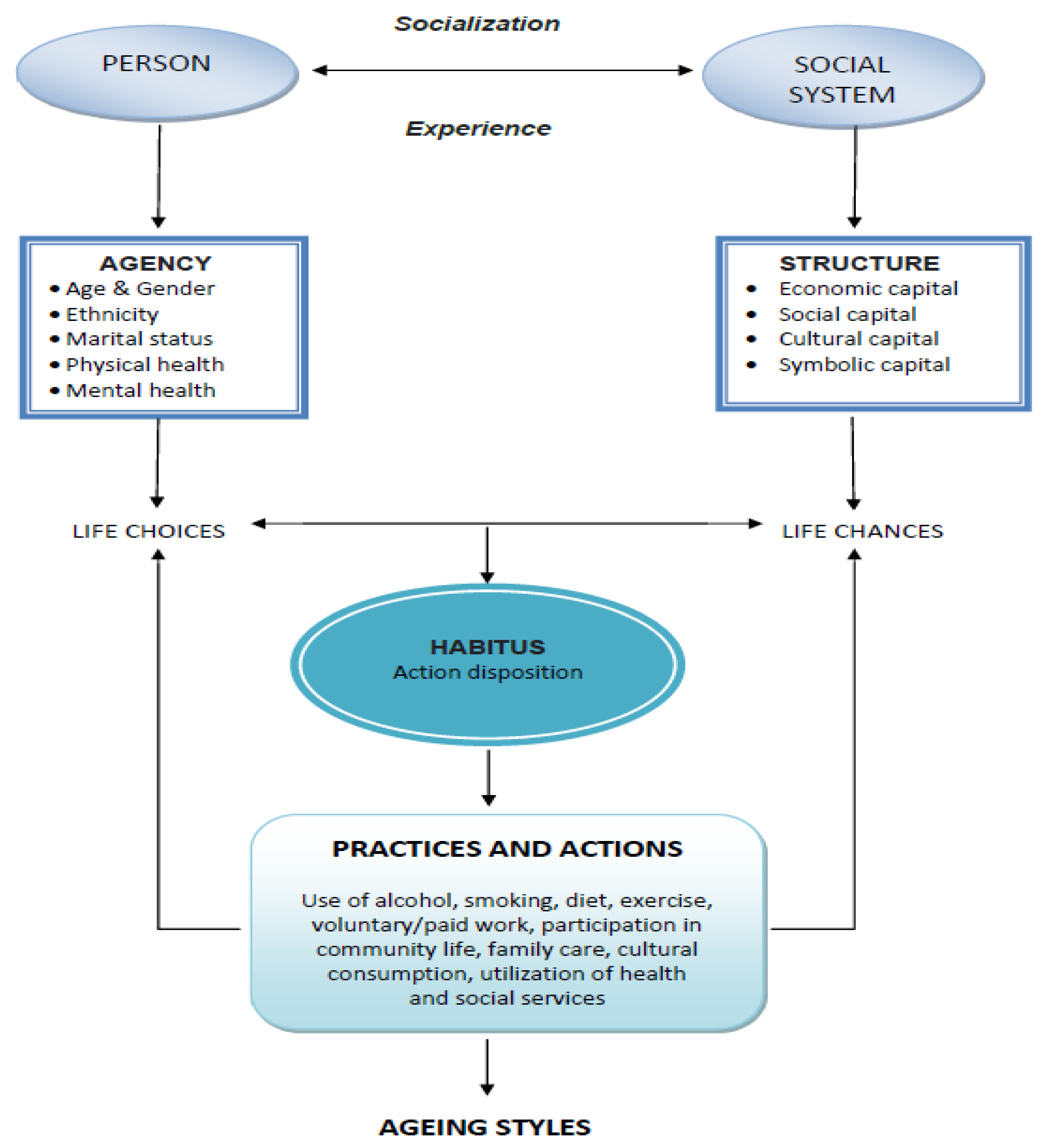

The model I propose (

Figure 2) is a variant of the Cockerham’s model with respect to two aspects. First, I prefer to use the denomination of “ageing styles” rather than health lifestyles to emphasize that the term focuses specifically on

ageing and not on

health in general, which is a broader phenomenon. And since ageing is a lifelong process, the term refers not only to the older adults, but to the entire human life. Secondly, the model is based on the ontological duality person-social system, which is constitutive of the sociological ambivalence of reality (Hillcoat-Nallétamby and Phillips, 2011; Merton and Barber, 2013). This duality implies that the person is not simply a puppet of the social system, and her agency is not

determined but only

conditioned by the social system. Therefore, variables such as

age, gender, ethnicity and

marital status, which were included in the structural variables in Cockerham’s model, are here considered components of

agency as part of the personal social identity together with physical and mental health, which were not included in Cockerham’s model. Furthermore,

socialization and

life experience are not considered simply as the result of structural variables, but as shown by the bidirectional arrow (

Figure 2), of the ambivalent relationship between

person and

social system: while on one side, the social system provides the framework of opportunities and constraints, on the other side the person through reflexive awareness (Bashkar, 1998; Archer, 2003) is able to exercise her agency in terms of

iteration (habit),

projectivity (imagination) and

practical evaluation (judgment) (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998). Finally, instead of considering social structure as composed of class circumstances, collectivities and living conditions as in Cockerham’s model, I prefer to use the terms proposed by Bourdieu (1986) to indicate a person’s capital endowment as a cause and effect of her position in the social structure:

economic capital (money and properties),

social capital (networks),

cultural capital (education) and

symbolic capital (social status and prestige).

For the rest, the model is similar to Cockerham’s, with two exceptions: the practices and actions that constitute the consequences of the habitus are more comprehensive, since the ageing process includes also voluntary or paid work, participation in community life, family care, cultural consumption, and utilization of health and social services, in addition to the classic quadriad of alcohol use, smoking, diet, and exercise; and a further arrow that goes from the practices and actions of ageing styles to life chances to indicate a potential retroactive feedback loop that changes the person’s capitals.

The proposed framework for analysing ageing styles can be used from a life course perspective to highlight their complex and dynamic nature. In fact, it recognises their complexity insofar it admits that “people’s behaviors do not always coalesce into concordantly ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’ patterns as implied by a single scale of healthfulness. (…) Discordance in lifestyles behaviors may represent important information that is lost when condensing data into a single healthfulness score. And the designation of behaviors as ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’ is a social construction that can change across time and place” (Mollborn et al., 2021: 391). Therefore, the framework does not adopt any predefined definition of “healthy” or “unhealthy” ageing styles but admits the possibility of finding concordant or discordant set of practices and actions within the same person. It can then be used to assess how and to what extent these ageing styles are related both to personal and social identity (agency) and/or to social position (structure).

Finally, the framework can situate ageing styles within the socially constructed nature of the life course to understand their dynamic nature in relation to any changes in either agency or a person’s social position: recognizing that social risks and resources are highly unequally distributed, and that the life course does not predetermines later life, which is the complex outcome of the relationship between agency and structure.

5. An Intersectional Methodology for Understanding Unequal Ageing Styles

The complex and dynamic nature of ageing styles is also the manifestation, like lifestyles in general (Mollborn et al., 2021: 391-395), of social inequalities: during the last two decades, the theory of cumulative advantages/disadvantages (Dannefer, 2003) has been widely adopted in social gerontology especially in relation to issues of heterogeneity and inequality. More recently, the intersectionality concept has been proposed in health inequalities research to address diverse inequalities, especially those concerned with forms of discrimination such as sexism and racism (Kapilashrami et al., 2015). However, “the intersectionality literature has paid very little attention to the nature of ageing or the life course, and gerontology has rarely incorporated insights from intersectionality” (Holman and Walker, 2021: 240). Therefore, a dialogue between intersectionality methodology and life course perspective is needed to advance our understanding of unequal ageing styles and, consequently, effective ways to counteract them.

The first important element intersectionality makes us to understand is that “people embody multiple social characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, age, socio-economic position (SEP) simultaneously. Combinations of social characteristics constitute different potential intersectional subgroups, for example a working-class 55-year-old Black woman. Intersectional subgroups represent (1) (objective) positions in the social hierarchy and (2) (subjective) social identities” (Holman and Walker, 2021: 240). Consequently, the identification of different intersectional subgroups of ageing styles, with specific attention to the most discriminated and marginalized people, represents the first step of an intersectionality methodological strategy. Discrimination can occur at different levels, which need to be identified: interpersonal, in face-to-face relationships; institutional, in the policies and practices of the state or other institutions; and societal, in society as a whole. These levels combine to form multiple systems of discrimination such as sexism, racism, classism and ageism, which interconnect to form what is called the “matrix of domination” (Collins, 2002). Gerontologist have examined, for example, the interplay between ageism and sexism (Krekula, 2007); even though, a recent systematic review has shown that only a few studies have examined the interactions between ageism and other forms of discrimination (Chang et al., 2020).

An important decision, in this respect, is to define “how each axis of inequality is categorised. Intersectionality prompts us to question traditional categorisations” (Holman and Walker, 2021: 241): In reality, just a few people are disadvantaged along all axes of inequality: generally, “a theoretical informed approach might focus on specific intersectional positions/identities” (Holman and Walker, 2021: 242). Furthermore, to avoid the “ecological fallacy” of stereotyping and stigmatising particular subgroups, intersectional patterning should consider that the diversity of population inequalities does not imply that membership in an intersectional subgroup automatically define individual experience due to the role of human agency in shaping individual heterogeneity. Qualitative methodologies are particularly suited to capturing the heterogeneity of human lives and their different intersections.

Once the categories for the axis of inequalities have been defined, the choice is between the two main intersectional approaches: the intercategorical one deals with differences between intersections, while the intracategorical focuses only within specific intersections. The choice depends on the research objectives: tipically, a focus on specific subgroups of marginalized intersections requires an intracategorical approach, whereas quantitative methodologies require an intercategorical approach to analyse differences between subgroups (McCall, 2005). From their analysis, two types of statistical effects can emerge: an additive effect, when a stratification of advantages/disadvantages occurs; or a multiplicative effect, when instead one social characteristic is amplified or attenuated by another. To distinguish these two possible effects, the MAIHDA (Multilevel Analysis of Individual Heterogeneity and Discriminatory Accuracy) programme is particularly appropriate, since it uses “multilevel models to nest individuals (level one) within their intersectional positions/identities (level two). Unlike conventional approaches involving interaction terms, the multilevel method can handle small intersectional subgroups due to statistical shrinkage inherent in the model. (…) Conceptually, the model takes intersectional subgroups as its unit of analysis and thus allows for socio-demographically ‘mapping out’ granular inequality” (Holman and Walker, 2021: 244). This attention to granular subgroups differences allows to estimate to what extent variance in findings can be attributed to differences between or within intersections.

Dressel and colleagues (1997) had already guessed the contribution of intersectionality to the understanding of systems of discrimination based on age, gender, ethnicity and social class across the life course, and the intersectional effects they produce in old age in terms of age as leveller, cumulative advantages/disadvantages and persistent inequalities. More recently, Holman and Walker (2021) have elaborated a more systematic attempt at a conceptual dialogue between intersectionality and life course perspective with a specific focus on understanding unequal ageing as a contribution to social gerontology. To this end, they preliminarily discuss some key concepts that can be usefully employed and then produce a series of guidelines which can be followed to analyse unequal ageing.

Role transitions is a first fundamental concept that can be revisited from an intersectionality perspective, examining how people move through different structural positions in the social hierarchy across the life course. This transition causes social identity and life experience to constantly evolve throughout the life span according to a timing that is intersectionally patterned: “intersectional patterning in how people move through life transitions can help to explain intersectional outcomes” (Holman and Walker, 2021: 247). There are certain intersectional categories, such as gender and ethnicity, which do not change over the course of a lifetime; others, such as marital status and social class, can instead change significantly. This is why a second fundamental concept in this respect is trajectory, which indicates how people navigate across various role transitions, their intersectional patterning and outcomes, such as health. An intersectional trajectory approach should therefore consider timing, sequences and turning points of different intersectional subgroups with respect to their ageing styles: this follows the first guideline proposed by Holman and Walker (2021: 250) stating that “people change intersectional subgroups over the life cycle and could therefore be said to follow an ‘intersectional trajectory’”.

A third useful concept is agency, since it can help to explain by an intersectional perspective “how social identities are fluid and multifaceted, and how the expression of agency is dependent on time and place” (Holman and Walker (2021: 248). Undoubtedly, the expression of agency is not entirely free, as it depends largely on both subjective (psychological characteristics, physical and mental health) and objective constraints (economic, social and cultural resources, institutional structures): and this is the main reason why many scholars tend to underestimate it. However, as we have seen, it can be usefully adopted to explain the variability of ageing styles according to different degree of control that people have over their roles and situations throughout their life course (Elder and Giele, 2009). We can probably assume, from an intersectional perspective, that this variance is related to intersectional subgroups, to their different levels of constraints and, consequently, of actual control over their lives and their ageing styles. In any case, even at the lowest levels of control and the highest levels of discrimination, people retain some degree of capacity to actively shape their social position and personal/social identity, and consequently their ageing styles, at least in terms of resistance and opposition to social constraints: and this follows the second guideline by Holman and Walker (2021: 250), which states that “people employ agency to resist discrimination and shape their own identities across the life cycle, within given constraints”.

The last three proposed guidelines are linked to two fundamental dimensions from an intersectionality perspective on ageing styles: historical time and spatial context. The first dimension may seem more obvious, since a life course approach is inherently longitudinal. However, it is not a given that categorization of intersectional subgroups depends on historical time: the meaning of retirement, gender, disability, or ethnicity today is rather different than it was one century ago. The same can be said for the second dimension of spatial context: different towns, metropolises, villages, regions or countries exhibit different intersectional diversities, so that intersectional subgroups take on different meanings in different spatial contexts. This is why the third guideline affirms that “Intersectional patterning and its significance for unequal ageing varies by historical time and spatial context” (Holman and Walker (2021: 250).

Different forms of discrimination are also significantly affected by historical time and spatial context: “experiences of discrimination vary by time and place depending on the prevalent ‘matrix of domination’” (Holman and Walker (2021: 251) is the third guideline. Individuals experience different types of interpersonal, institutional and societal discrimination according to norms, stereotypes, prejudices and discriminatory mechanisms such as the labelling of individual potential, internalised incompetence, and exposure to institutional policies. And the impact of these different forms of discrimination on unequal ageing styles depends primarily on life course dynamics, such as timing, critical periods, sequential effects. Therefore, the fourth guideline states that “people are affected by multiple forms of discrimination over the life cycle and according to historical time and spatial context” (Holman and Walker (2021:251).

Finally, social policies and institutional practices, such as the welfare state, immigration policy, social care, retirement policy can be more or less discriminatory, depending on historical time and spatial context. Therefore, it is necessary to analyse how policies and institutional practices discriminate on the basis of both single or multiple axes of inequality at a time (ageism, sexism, racism, etc.) and in which wider socio-political context (e.g., austerity, neoliberalism, etc.): “people are simultaneously affected in different ways by multipole overlapping policies depending on their intersectional position” ((Holman and Walker, 2021: 249). This is what Beckfield and colleagues (2015) call “institutional imbrication”: institutions mediate people’s intersectional trajectories, potentially leading to exclusion and marginalisation. The “matrix of domination” changes over historical time and spatial context: ageism, e.g., has significantly changed its stereotypes from physical limitations to cosmetic appearance, with serious effects particularly on older women and their ageing style (Twigg, 2013). At the same time, health and social policy can mitigate and compensate the impact of discrimination on ageing styles by the availability of health care and social services. The fifth and last guideline summarizes all these factors by stating that “Ageism, sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination and their interconnections (the ‘matrix of domination’) vary by historical time and spatial context” (Holman and Walker (2021: 251)).

6. Conclusions: An Evidence-Based Policy Strategy for European Countries

At the end of our long excursus, it is useful to try to synthesize it to assess how it could represent a valid scientific support for an evidence-based European political strategy aimed at promoting active ageing from a perspective of intergenerational fairness.

Our starting point has been demographic trends in Europe, which show an advanced situation of population ageing, raising urgent challenges for intergenerational equity: in particular, the two fundamental pillars of European post-industrial societies, namely an extensive welfare state and a liberal-democratic institutional framework, appear to be at risks. Although there is no real intergenerational conflict, the intergenerational social contract that remains one of the foundations of European liberal democracies is being called into question both formally (with regard to welfare state, based on the principles of equity and equality) and informally (within the family, based on the principle of reciprocity). To address this issue, the notion of “intergenerational fairness” recently adopted by social policies in both USA and Europe, appears flexible and fundamentally ambiguous. As a substantial variant of neoliberal austerity policies, it is simply used as a justification for further austerity measures, the withdrawal of entitlements to social and economic rights by citizens and the dismantling of welfare states. A second meaning of “intergenerational fairness” is possible starting from the concept of ambivalence used to describe the mix of conflict and solidarity that characterizes intergenerational relations in contemporary post-industrial societies. This implies that is not possible to ignore the role that variables such as social class, gender, ethnicity and marital status play in intergenerational inequality: to achieve this, a lifelong approach is needed that examines the role of all these variables as enablers or barriers throughout people’s life course. It is therefore necessary to move from an exclusive focus on intergenerational fairness to ageing as a lifelong process and the result of the intersection of all the above variables in post-industrial societies.

In this respect, the two concepts of “successful ageing” and “active ageing”, often considered as overlapping, actually involve very different perspectives: successful ageing adopts a substantially reductionist, individualistic and static approach to the process of ageing, whereas active ageing is a more comprehensive and dynamic strategy that seeks to overcome all these limitations by a life course perspective. It recognizes that a person’s path to old age is not predetermined but depends primarily on earlier life experiences and their influence: the ageing process affects people of all ages, not just the elderly. And since the subjectivization of ageing in contemporary societies has challenged the conventional notion of “natural life stages”, the new concept of ageing lifestyles becomes central to understanding the ageing process today. Based on the concept of lifestyle discussed in classical sociological theory since Weber to Giddens and Bourdieu, and the theory of health lifestyles proposed by Cockerham, ageing styles are the outcome of the interplay between the objective and subjective dimensions of the life course, represented respectively by the life chances (social structure) and the life choices (agency).

The proposed framework for analysing ageing styles can be used from a life course perspective to highlight their complex and dynamic nature. To this end, the methodology of intersectionality is particularly suited to address diverse health inequalities, especially those linked to forms of discrimination such as ageism, sexism, and racism, which are at the origin of unequal ageing styles. Key concepts of role transitions, trajectory, agency, historical time and spatial context that can be employed for sorting out intersectional subgroups are illustrated, along with five guidelines which can be followed to analyse unequal ageing styles and identify the prevailing “matrix of domination” that originate them.

Is it possible to utilise the theoretical and methodological design described above to support a European policy strategy aimed at addressing the problem intergenerational inequity we discuss at the beginning? The answer can be positive, given a series of conditions that can be summarised in a comprehensive and inclusive vision of active ageing based on intergenerational fairness. Foster and Walker (2014: 2021) have already sketched the eight key principles which can be adapted to ageing styles to foster a comprehensive and inclusive strategy. The first is that the concept of “activity” should encompass any activity that can contribute to individual health and well-being, including unpaid voluntary work, social participation, leisure, and family care, all included in ageing styles: this to avoid productivist definitions of active ageing that simply focus on extending working life. Second, the strategy should be primarily prevention-oriented and include all age groups in the process of ageing actively across the life course. Third, active ageing activities should involve all older people, including those frail and dependent, in order to avoid the risk of excluding the “old-old”: obviously, this implies that they should be scaled according to the individual’s level of self-sufficiency. Fourth, intergenerational solidarity should be a key component of an active ageing strategy aimed at preserving and renewing the intergenerational social contract. Fifth, the approach to active ageing is two-fold, meaning it includes both rights (to social proception, lifelong learning, etc.) and obligations (willingness to participate in activities, remain active, etc.). Six, active ageing strategies should not only be top-down but should promote actions and resources to empower people and facilitate their actual participation in activities. Seven, as we have seen, “active ageing” can take on different meanings according to different contexts and times: it is therefore essential for any non-ethnocentric strategy to be respectful of the national and cultural diversity across the different European macro-regions both in defining activity patterns and in considering the related social norms. Lastly, an evidence-based European political strategy aimed at promoting active ageing from a perspective of intergenerational fairness should be flexible enough to ensure that everyone can adopt their preferred ageing style without top-down imposition, and can change their preferences and life choices: “active ageing policies assist people to accept changes and integrate them into their lives” (Foster and Walker, 2021: 7).

A comprehensive and inclusive vision of active ageing based on intergenerational fairness according to the above principles can foster subjective variability in individual adaptive responses to aging and the growing plurality of aging styles, thus contributing to the maintenance of the intergenerational social contract.

Author Contributions

The article is entirely original and written by the author.

Funding

This article received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

As it is known, the European Union does not include all European countries, but only 27 out of 44 if we exclude transcontinental states such as Russia and Türkiye. |

| 2 |

The model of “health macro-region” I proposed (Giarelli, 2021) refers to a ‘family’ of health systems which shares a similar pattern of historical, ecological, epidemiological, political, economic, social and cultural characteristics. By this model, I developed a classification of European health systems articulated into five main macro-regions (Giarelli and Saks, 2024): the Northern Macro-region, including the Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Norway, Finland, Iceland, Denmark); 2) the British-Irish Macro-region, including United Kingdom and Ireland; 3) the Central-Western Macro-region, including France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Netherlands, Switzerland and Luxembourg; 4) the Central-Eastern Macro-region, including Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Romania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania; and 5) the Southern or Mediterranean Macro-region, including Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Malta and Cyprus. The other countries of the Balkans and Eastern Europe were not included because of their different situation. |

References

- Arber, S.; Attias-Donfut, C. Equity and solidarity across the generations. In The Myth of Generational Conflict: The Family and State in Ageing Societies; Arber, S., Attias-Donfut, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M.S. Structure, Agency and the Internal Conversation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L. Are older adults perceived as a threat to society? Exploring perceived age-based threats in 29 nations. J. Gerontol. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74B, 1256–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, A.E.; Barbee, H. The subjective life course framework: Integrating life course sociology with gerontological perspectives on subjective aging. Adv. Life Course Res. 2022, 51, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckfield, J.; Bambra, C.; Eikemo, T.A.; Huijts, T.; McNamara, C.; Wendt, C. An institutional theory of welfare state effects on the distribution of population health. Soc. Theory Health 2015, 13, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. The Possibility of Naturalism, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, D.; Kelly, P. The social contract and its critics. In The Social Contract from Hobbes to Rawls; Boucher, D., Kelly, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Boudiny, K. ‘Active ageing’: From empty rhetoric to effective policy tool. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 1077–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, M. Intergenerational help and public assistance in Europe A case of specialization? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 15, 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Successful ageing and the role of the life review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1974, 22, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.-S.; Kannoth, S.; Levy, S.; Wang, S.-Y.; Lee, J.E.; Levy, B.R. Global reach of ageism on older persons’ health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0220857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, B. Intergenerational inequality? Labour, capital, and housing through the ages. Antipode 2018, 50, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Warren, L. Hopes, fears and expectations about the future: What do older people’s stories tell us about active ageing? Ageing Soc. 2007, 27, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerham, W.C. Health lifestyle theory and the convergence of agency and structure. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerham, W.C. Health lifestyle theory. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Theory; Turner, B.S., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham, W.C.; Wolfe, J.D.; Bauldry, S. Health lifestyles in late middle age. Res. Ageing 2020, 42, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cribb, J.; Hood, A.; Joyce, R. Entering the Labour Market in a Weak Economy; IFS Working Paper Series; Institute for Fiscal Studies: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, E.; Henry, W.E. Growing Old: The Process of Disengagement; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer, D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J. Gerontol. 2003, 58, S327–S337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Barrio, E.; Marsillas, S.; Buffel, T.; Smetcoren, A.-S.; Sancho, M. From active aging to active citizenship: The role of (age) friendliness. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]