1. Introduction

While research evidence has long suggested that workplace sexual harassment (SH) is associated with acute health symptoms, for example headaches, gastrointestinal complaints, problems sleeping (Magley, Hulin, Fitzgerald, & DeNardo, 1999; Wasti, Bergman, Glomb, & Drasgow, 2000; Willness, Steel, & Lee, 2007), few studies have examined diagnosed health conditions as outcomes of exposure to harassment in U.S. based samples. Exceptions are recent evidence from a study of midlife women indicating that those with prior exposure to SH had significantly higher odds of hypertension (Thurston, Chang, Matthews, Von Känel, & Koenen, 2019), a meta-analysis showing increased risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood among those with a lifetime history of exposure to sexual violence, including sexual harassment (Jakubowski, Murray, Stokes, & Thurston, 2021), and a cohort study of Swedish workers demonstrating that past 12 months exposure to workplace SH was associated with increased incidence of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, particularly for those with frequent SH exposure (Prakash, et al., 2024). Recently, Abdullah et al., in the first study to examine long-term health effects of exposure to SH among both women and men who were initially sampled from a U.S. Midwestern urban university, found that exposure to a pattern of prior chronic SH between 1996-2006 was associated with increased odds of being diagnosed with arthritic or rheumatic conditions during the study period ending in 2020 (Abdulla, Lin, & Rospenda, 2023). One limitation of this research is that, with the exception of Abdullah et al., SH exposure was operationalized in such a way that it required participants to recognize and label their experiences as sexual harassment. Research has found that SH can negatively impact targets’ health even if they don’t directly label their experiences as sexual harassment (Magley et al., 1999). Thus, prior research may be inaccurately capturing the full impact of SH on health.

Another issue with prior research is that it has not accounted for other potential health correlates of both harassment and chronic disease. Two factors that are known correlates of both exposure to workplace harassment and chronic disease are alcohol use or misuse and depression. A large body of longitudinal research has accumulated documenting the negative effects of SH on symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD (see Chan, Chow, Lam, & Cheung, 2008; Diez-Canseco, Toyama, Hidalgo-Padilla, & Bird, 2022; Willness et al., 2007 for reviews). Additionally, Rugulies and colleagues found that onset of workplace sexual harassment in the 12 months prior to a 2014 survey was associated with incidence of depressive disorder in 2014 for a sample of almost 10,000 Danish workers (Rugulies et al., 2020). Similarly, while less prolific, alcohol research has consistently shown that SH is associated with increases in alcohol use and misuse (Richman, Shinsako, Rospenda, Flaherty, & Freels, 2002; Rospenda, Fujishiro, McGinley, Wolff, & Richman, 2017; Rospenda, Richman, & Shannon, 2009), and with alcohol-related morbidity and mortality (Blindow, Thern, Hernando-Rodriguez, Nyberg & Magnusson Hanson, 2023). Both poor psychological distress and alcohol use/misuse have been shown to predict onset of illness or disease. For example, depression is associated with development or worsening of cardiac issues (Ferketich, Schwartzbaum, Frid, & Moeschberger, 2000; Pratt et al., 1996) and diabetes (Eaton, Armenian, Gallo, Pratt, & Ford, 1996; Graham et al., 2020), and a causal association has been established between alcohol use and cancer risk (Boffetta & Hashibe, 2006; LoConte, Brewster, Kaur, Merrill, & Alberg, 2018). Heavy drinking is additionally associated with risk for heart disease, stroke, and cirrhosis of the liver (see Rehm et al., 2017 for a review). Thus, when investigating the association of SH with chronic disease, it is important to account for the effects of psychological distress and drinking behavior.

In this paper, we address the limitations of existing research by examining the impact of SH as measured by responses to a multi-item scale on diagnosis of chronic disease across a 23 year study period, accounting for recent symptoms of depression and use of alcohol. Data from a longitudinal study, originally sampled from a cohort of university employees surveyed in multiple waves from 1996 to 2007 and again in 2020-2021, is used to examine the effect of harassment in the workplace on the hazard of first diagnosed chronic disease. These data expand on data previously reported in Abdullah et al. (2023) by testing a data analytic approach that allows SH exposure to vary over time, and by accounting for symptoms of depression and alcohol use as potential explanatory mechanisms). We hypothesize that exposure to SH will be associated with onset of chronic disease during the study period, controlling for depression and alcohol use.

2. Materials and Methods

Recruitment and Study Population: Study participants were originally recruited in 1996 from a sample of 4832 employees of an urban Midwestern university in the United States. The investigative team were researchers from the same university, none of whom were affiliated with university administration. The original purpose of this prospective cohort study was to examine workplace harassment as a risk factor for alcohol use and misuse, in the context of other psychosocial stressors and life experiences. The sample was stratified by gender (50% women, 50% men) and occupational group (faculty, graduate student workers/trainees, clerical/administrative workers, service/maintenance workers). Occupational groups were selected to ensure a broad representation of different occupations, as most SH research at the time was being conducted on samples of students and faculty only. All participants had access to medical insurance and the Employee Assistance Program or student mental health services support during their employment at the university.

At baseline (survey period from October 1996 to February 1997; T1), N=2492 individuals responded to the survey (52% response rate). Study participants completed questionnaires asking about their experiences of workplace harassment, symptoms of depression, and alcohol use at baseline and then at eight additional time points through February of 2021 (T9). Surveys were administered at approximately 12 month intervals between 1996 and 2008, with the exceptions being gaps of three years between the 1998 and 2001 surveys, two years between the 2003 and 2005 surveys, and 12 years between the 2008 and 2020 surveys. Time point nine (June 2020 – February 2021; T9) occurred on average 23 years following baseline. The T9 survey included questions about retrospective reports of chronic disease diagnosis, including age at first diagnosis. Those who responded at baseline were resurveyed throughout the entire study regardless of whether they remained employed by the university. A total of n=780 valid responses were received at T9. At all survey time points, potential respondents were provided with information about the study and potential risks and benefits of participation and asked to express consent by returning a completed questionnaire. Respondents were compensated $20 at T1 and $40 at T9. Survey data were collected by a survey laboratory affiliated with the university at T1, and by a survey lab affiliated with a different university at T9. The study was approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board (protocol 2019-0374).

The analysis sample (n=488) is selected from all subjects who retrospectively reported age at first diagnosis when surveyed at T9, who had not had any chronic disease diagnosis yet at one year after baseline, and who were not missing baseline values for predictor variables or covariates discussed below. To maintain timing consistent with causality, risk of new chronic disease diagnosis in any given year is predicted from time-dependent measures reported one year earlier; therefore the observed event times, or first diagnoses, start one year after baseline.

Exposure Variables: Workplace sexual harassment experiences (SEQ) in the 12 months prior to each survey were assessed using a version of the 19-item Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (Fitzgerald, 1996) with wording modified to be applicable to both men and women. Respondents indicated the frequency of experience of gender harassment (e.g., told suggestive stories or offensive jokes), unwanted attention (e.g., unwanted attempts to stroke or fondle you), and sexual coercion (e.g., implied faster promotions or better treatment if you were sexually cooperative) on a 3-point scale: 0=never, 1=once, or 2=more than once. Coefficient alpha reliability for the overall scale was 0.80 or higher at each data collection point.

Number of drinks consumed per day (DRINKS) was measured at each survey time point with the item, “When you drank any type of alcoholic beverage during the last 30 days, how many drinks did you usually have per day? (One drink would be equal to one 5-ounce glass of wine, one can/bottle of beer, or one shot of whiskey/hard liquor.)” Responses were reported on a scale from 0=none/never drank in the past 30 days to 7=more than 6 drinks.

Symptoms of depression (DEPR) in the past 7 days were measured at each survey time point with seven items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CESD) (e.g., I could not shake off the blues; I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing) which correlate highly with the full CESD (Mirowsky & Ross, 1990). Items were scored on a scale from 1=rarely or none of the time – under 1 day, to 4=most or all of the time – 5-7 days. Higher scores indicate greater symptoms of depression. Coefficient alpha reliability for the overall scale was 0.80 or higher at each data collection point.

Chronic Disease Incidence: Age at first diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, asthma, cancer, diabetes, or arthritic disease is calculated from retrospective self-reports of chronic disease diagnosis history at the wave of followup. The number of years from baseline to first chronic disease diagnosis is calculated from age at baseline and age at first diagnosis reported for those with observed events times. Right-censored event times are number of years from baseline until last measurement wave for those reporting no chronic disease diagnoses.

Covariates: Adjustment variables at baseline to be considered include race, gender, and the four occupational groups used as strata for the survey (faculty, graduate students, clerical/administrative, service/maintenance). Current age is included as a time-dependent variable calculated from age at baseline and current survey year. Variables whose effects are not statistically significant at α=.05 are excluded to preserve power.

Statistical Analysis: The distribution of race, gender, occupation, age at baseline, and values of workplace sexual harassment (SEQ), average drinks per day (DRINKS), and symptoms of depression (DEPR) at baseline are summarized using descriptive statistics. The estimated incidence curve for the outcome, years until first chronic disease diagnosis, is displayed and median survival time reported.

Proportional hazards multiple regression models are used to model the hazard of first chronic disease diagnosis across the entire followup period. Occupational group (four categories used as part of the study design) as determined at baseline of the study is included as a fixed covariate. Current age is included as a time-dependent covariate, calculated from reported age at baseline and years between baseline and followup waves. Variables SEQ, DRINKS and DEPR were considered as both fixed at baseline and as time-dependent covariates reflecting repeated measurements during each previous year.. Across repeated surveys, if a time-dependent covariate is not reported, the last previous reported value is used (“last value carried forward”). Race and gender are evaluated and added for adjustment if their effect in the model is significant at α=.05. For factors not included due to nonsignificant main effects, each main effect and interaction are added and tested for significance to explore whether the effect of SEQ varies with the factor.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 is a summary of the analysis sample at baseline. The sample size of 488 is a result of selecting those who report age at first diagnoses at last followup, who had not yet experienced a first chronic disease diagnosis one year after their baseline survey, and who are not missing demographics or baseline reports of SEQ, DEPR, and DRINKS. For comparison we show characteristics of subjects excluded from the analysis sample.

3.2. Chronic Disease Incidence

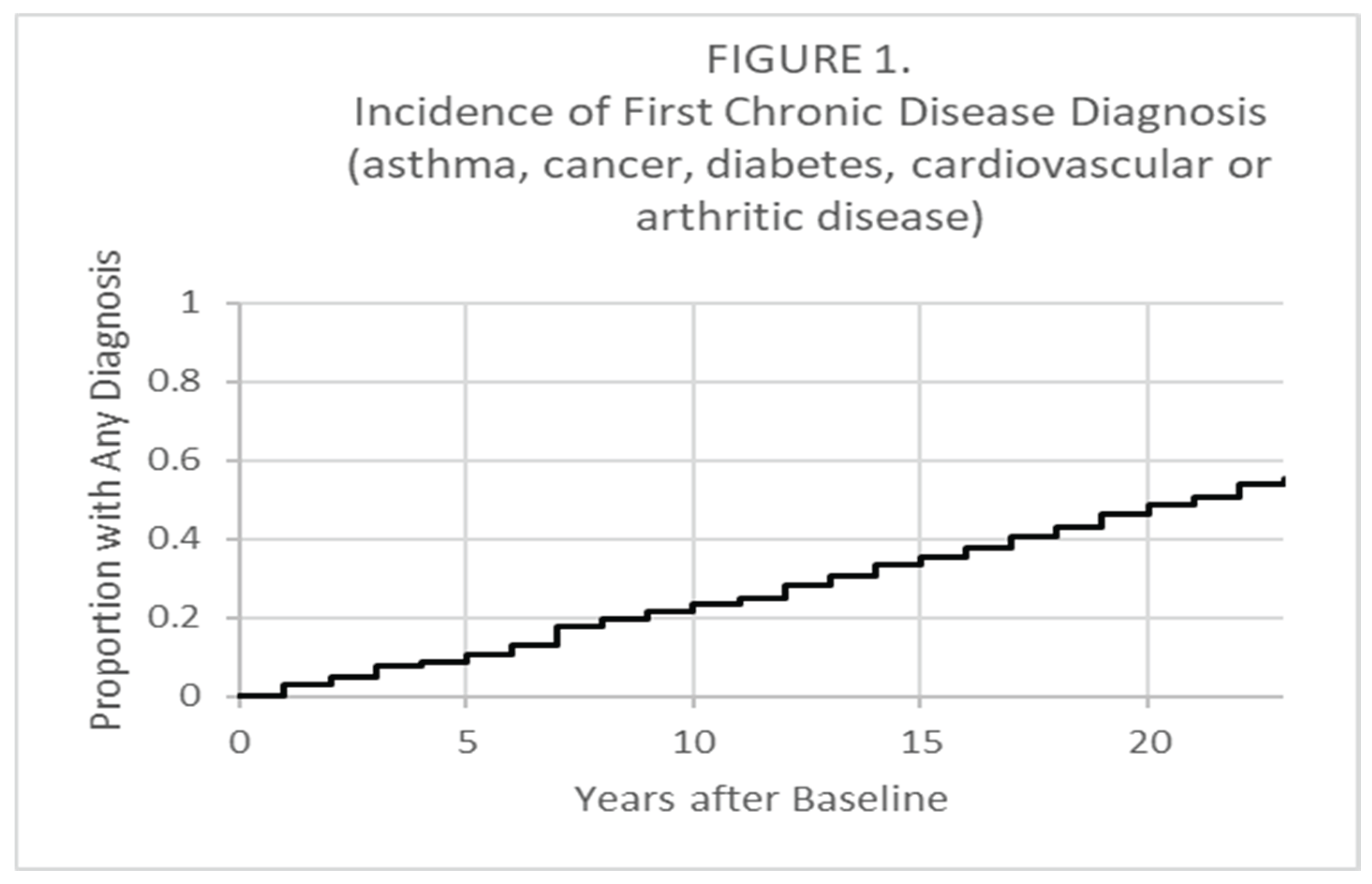

Out of the 488 at risk one year after baseline, there were 269 first diagnoses reported ranging from 1 year to 23 years after baseline, with 219 still right-censored (no first chronic disease diagnosis reported) at the end of followup as shown in Figure 1. Median time to first diagnosis was 21 years (95% C.I. [19, 23]). The most common first chronic disease diagnosis was cardiovascular disease (46%), followed by arthritic disease (24%); cancer (15%); diabetes (9%); and asthma (6%).

3.3. Proportional Hazards Model Results

The effect of race/ethnicity using various coding schemes (White vs. Other; Black vs. Other; four factors grouping Hispanic with Other; four factors grouping Asian with Other), as well as the effect of gender, did not have statistically significant effects on the hazard of first chronic disease diagnosis (α=.05) and were therefore excluded from our models. The factor consisting of four occupation categories at baseline did have a significant effect (X2=13.25, df=3, p=.0041). Examination of the effect of current age revealed the use of two indicators, current age > 40 (HR=1.77, p=.0200) and current age > 50 (HR=2.000, p<.0001) best captures the effect on risk of first diagnoses.

The effect of SEQ was tested both as fixed at baseline and as a time-dependent covariate. SEQ fixed at baseline (HR=1.038, p=.0133) was found to have a slightly stronger effect than SEQ as a time-dependent covariate (HR=1.034, p=.0266), so SEQ at baseline and was included in the model as the main effect of interest. DRINKS and DEPR were each considered as both fixed at baseline and as time-dependent covariates allowed to change across followup, added one at a time to the model with SEQ at baseline. Significant effects were found for DEPR fixed at baseline and for DRINKS as a time-dependent covariate.

Adjusting for occupation at baseline and current age,

Table 2 shows results for models including SEQ at baseline (Model 1); adding DEPR at baseline (Model 2); and further adding DRINKS as a time-dependent covariate (Model 3). The significant effect of SEQ in Model 1 remains significant and only somewhat attenuated adjusted for a significant independent effect of DEPR at baseline. Both SEQ and DEPR exhibit the strongest effects as fixed covariates at baseline, and accounting for their changes across followup does not increase their ability to predict chronic disease incidence. DRINKS, on the other hand, has a significant effect as a time-dependent covariate updated across followup but is not significant if fixed at baseline.

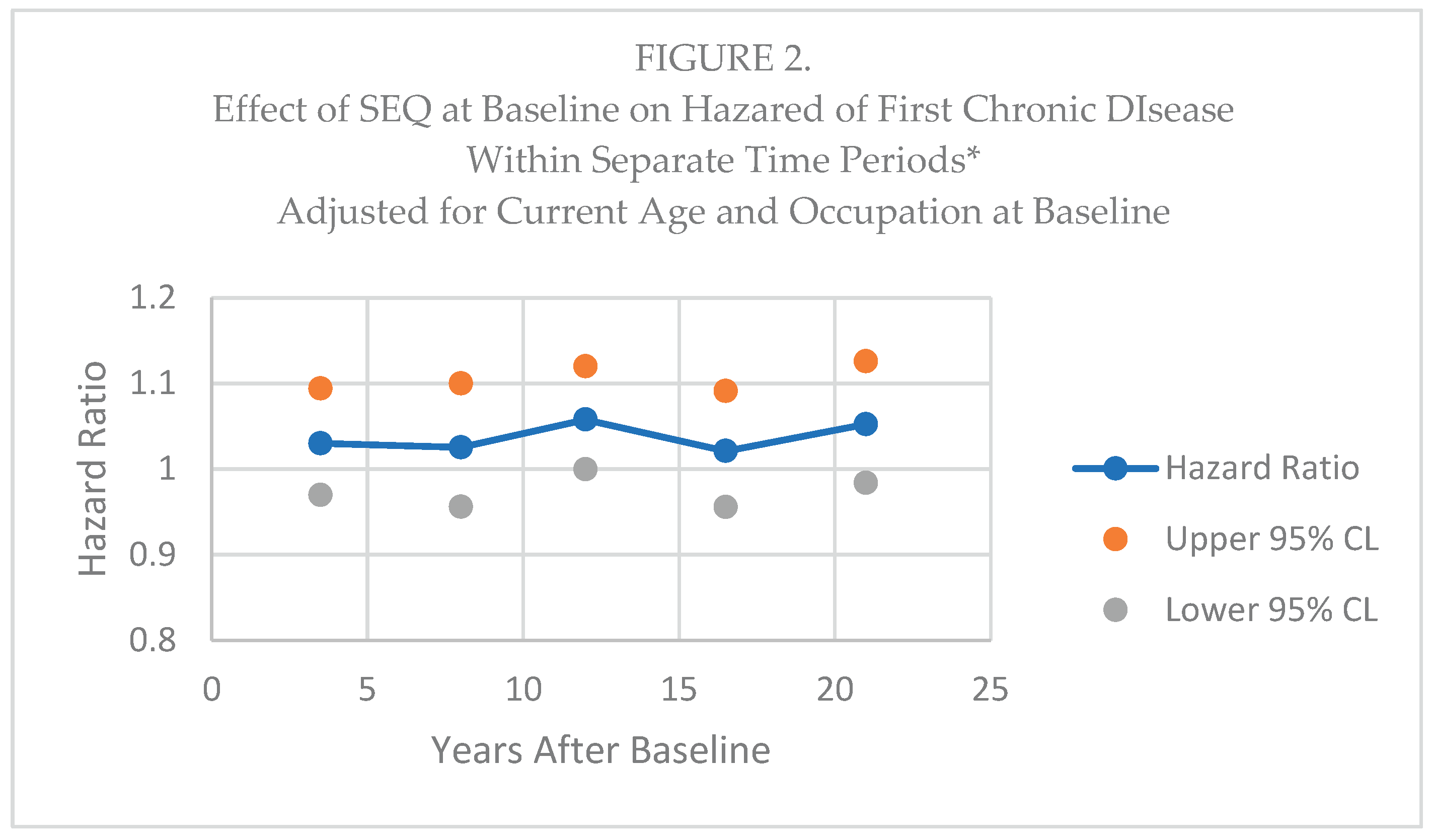

The effect of SEQ was explored further to see if it decreased across the followup period. Standard tests for the assumption of proportional hazards did not detect any systematic change with time (p=.5247) or with the natural logarithm of time (p=.4184) suggesting that the effect does not systematically increase or decrease across followup. Figure 2 shows estimated effects within five separate time intervals. While the separate effects are not statistically significant due to low power, there is no sign of a decreasing effect across followup.

*Intervals are 1-6 years (64 diagnoses); 7-10 years (50 diagnoses); 11-14 years (50 diagnoses); 15-19 years (62 diagnoses); and 20-23 years (44 diagnoses).

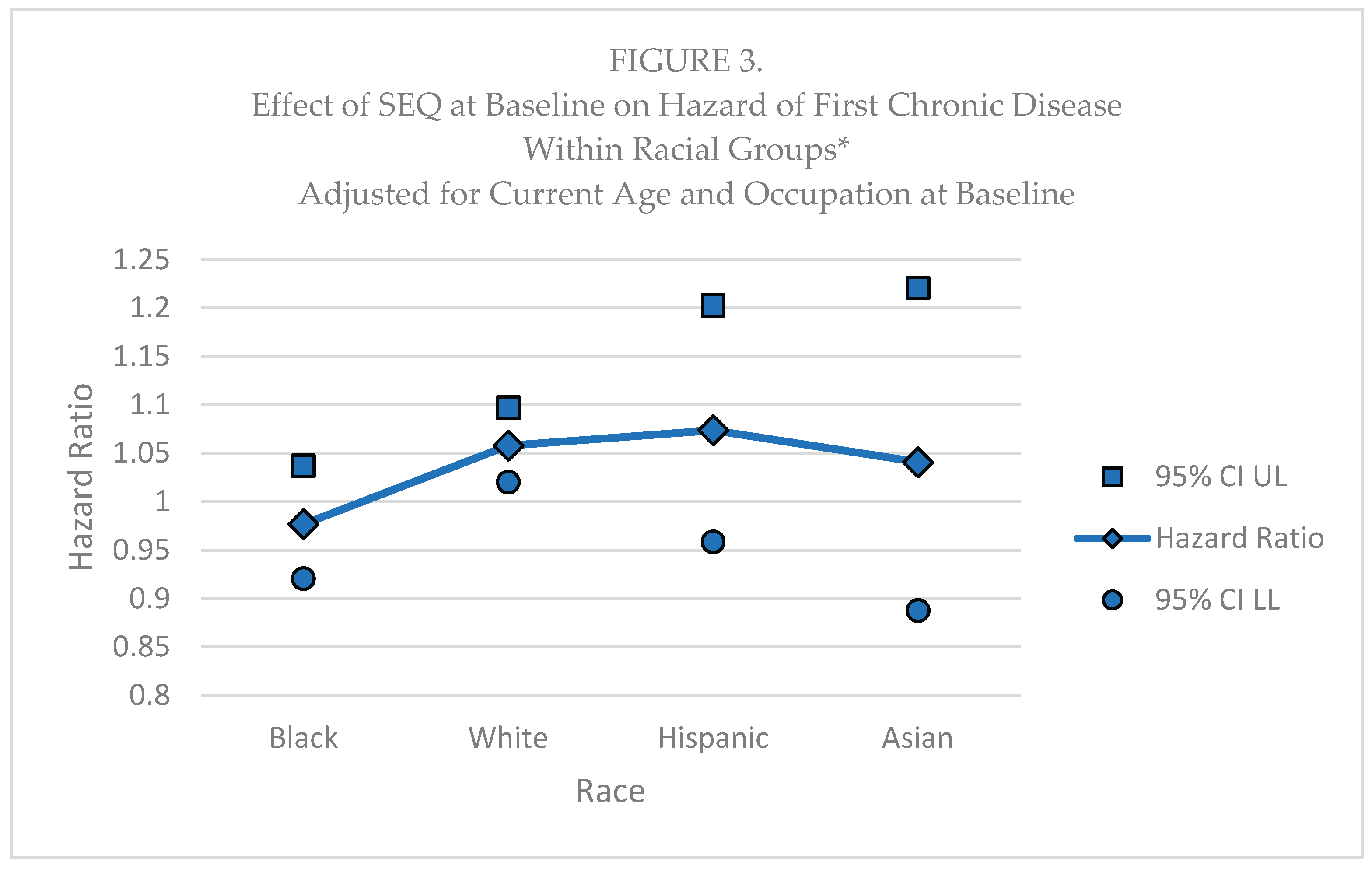

Additional analysis was done to examine interactions with SEQ using one degree-of-freedom tests for the interaction between each occupation group and SEQ, and two degrees-of-freedom tests for the additional of the main effect plus the interaction for gender and for each racial group. No significant interactions were found for occupational group or gender (α=.05). Addition of the main effect of Black race plus the interaction with SEQ was significant (X2=7.398, df=2, p=.0247) and includes an interaction term suggesting a weaker effect in Blacks (p=.0192). Adding the main effect and interaction for white, Asian, or Hispanic did not improve the model. Models were then fit allowing for different estimates of the effect of SEQ, across the entire time span, within each racial group to describe differences by race (Figure 3).

*Black (n=73, 53 diagnoses), White (n=328, 181 diagnoses), Hispanic (n=23, 23 diagnoses), Asian (n=58, 12 diagnoses), Other (n=6, 0 diagnoses, not shown).

4. Discussion

These analyses build on our prior work demonstrating the long-term effects of exposure to chronic sexual harassment on onset of disease (Abdulla et al., 2023) We also explored alcohol consumption and depression as both fixed covariates at baseline and as time-dependent covariates allowed to change across the followup period. Notably, the effect of alcohol consumption in the previous year remains significant in the final model, which is consistent with a growing body of literature on the relationship between alcohol use/misuse on morbidity (e.g., Rehm et al., 2017) and mortality (e.g., Rehm & Shield, 2013).

Interestingly, the relationship between sexual harassment and disease onset did not differ significantly by occupational group or by gender. The lack of differential effects by gender is consistent with our prior research, and further demonstrates that the general cultural perception that sexual harassment is a “women’s problem” should be discarded. However, there was a significant difference in the effect by race/ethnicity, with White respondents exhibiting the strongest effects of harassment exposure. Failure to detect significant effects for members of minority groups may be a consequence of the smaller sample sizes and number of diagnoses available for each. It is also possible that the measure used in the present study fails to capture the full experience of sexual harassment for racial/ethnic minority group members. Prior intersectional research has demonstrated that women of color in particular may experience “racialized sexual harassment,” or harassment that combines aspects of both racism and sexism (Buchanan & Ormerod, 2002). Additionally, workers of color are more likely to experience other stressors and forms of discrimination (e.g., racial discrimination, institutionalized racism) (Williams, 2018) in the workplace, which were not captured in the present study. Future research is needed to examine the relative contribution of multiple distinct psychosocial hazards in the workplace, including sexual harassment, racial discrimination, workplace bullying, and other harmful exposures to worker health over time.

Strengths: Multiple repeated waves of data allowed for use of a model requiring exposure measurements to be completed at least one year prior to disease incidence. Resulting significant associations are more likely to be causal in nature. There were a wide variety of occupations represented in the sample,which included men, unlike much of the research on sexual harassment, and the sample was racially- and ethnically diverse. Additionally, we accounted for depressive symptoms and alcohol use, known correlates of both SH and health, allowing for a more nuanced assessment of the impact of SH on development of chronic health conditions.

Limitations: Our results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. The sample was originally drawn from a single urban Midwestern university in the United States, potentially limiting generalizability. Additionally, recruitment of participants at baseline was conducted by a survey organization that was affiliated with the university, and study investigators were associated with the university. Respondents may have underreported SH, alcohol use, and depressive symptoms to the extent that they were uncomfortable disclosing such information to study investigators at the same institution, or may have declined to participate in the study entirely. To help improve sense of anonymity, surveys were identified by unique id number only. Another limitation is that, for those who changed jobs, we did not collect information about the benefits and resources available to those individuals at their new jobs. Those who moved to jobs without health benefits, or with reduced benefits, may have been more likely to suffer adverse health outcomes. Also, the analytic sample size was relatively small, and subject to possible selection bias due to disproportionate dropout of those who experienced SH or developed/succumbed to chronic disease during the course of the study. The size of the analytic sample also limited power to detect significant associations with onset of disease, particularly among non-White racial-ethnic subgroups , and resulted in insufficient power to assess disease-specific associations. Future research would benefit from larger, representative samples, and more non-response follow-up to attempt to determine reasons for survey non-response.

Also, data were collected from self-report surveys and are subject to self-report bias, and there was a large gap in data collection between the original study (T1-T8) and follow-up at T9, leading to a loss of information about study variables during this intervening period. Additionally, diagnosis information was collected only at T9, and as such are at risk of recall bias, particularly for less recent diagnoses. Future research should investigate the long-term impacts of exposure to sexual harassment on health using more frequent data collection points, and should attempt to corroborate reported diagnosis of chronic health conditions with data from medical records. Additionally, future research would benefit from more detailed exploration of exposure to sexual harassment by race, gender, and occupation, whether long-term health outcomes differ by these demographic characteristics, and how the course of exposure to harassment develops for different groups of individuals.

5. Conclusions

Despite study limitations, these results are important for several reasons. This is the first study to demonstrate that experience of sexual harassment in the workplace is associated with increased risk for subsequent onset of chronic disease, and this effect does not diminish over time. Depression and alcohol consumption also contribute to chronic disease incidence in our model, but they do not account for the effect of sexual harassment, suggesting they are not mediating the effect. Additionally, our research suggests the importance of strengthening anti-sexual harassment campaigns to reduce the impact of this preventable workplace exposure on the health of the working population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F., T.L., T.J., and K.R.; methodology, S.F., T.L., T.J., and K.R.; formal analysis, S.F.; investigation, K.R.; resources, K.R.; data curation, K.R.; writing - original draft S.F.; writing - review and editing, S.F., T.L., T.J., and K.R.; visualization, S.F.; supervision, K.R.; project administration, K.R.; funding acquisition, S.F., T.L., T.J., and K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The results herein correspond to specific aims of grant R01AA026868 to the first author from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The work was also supported by grant R01AA099898 to Judith A. Richman. The funding body did not have a role in the design of the study or collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of University of Illinois Institutional Review Board (protocol 2019 0374). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were provided with informed consent information prior to study participation and consented to participate in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data used for analysis in this paper are available from the first author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdulla, A. M., Lin, T. W., & Rospenda, K. M. (2023). Workplace harassment and health: A long term follow up. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 65(11), 899-904. [CrossRef]

- Blindow, K. J., Thern, E., Hernando-Rodriguez, J. C., Nyberg, A., & Magnusson Hanson, L. L. (2023). Gender-based harassment in Swedish workplaces and alcohol-related morbidity and mortality: A prospective cohort study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health(6), 395-404. [CrossRef]

- Boffetta, P., & Hashibe, M. (2006). Alcohol and cancer. The Lancet Oncology, 7(2), 149-156. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, N. T., & Ormerod, A. J. (2002). Racialized sexual harassment in the lives of African American women. In C. M. West (Ed.), Violence in the lives of Black women: Battered, Black, and blue (1 ed., pp. 107-124). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Chan, D. K. S., Chow, S. Y., Lam, C. B., & Cheung, S. F. (2008). Examining the job-related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 362-376. [CrossRef]

- Diez-Canseco, F., Toyama, M., Hidalgo-Padilla, L., & Bird, V. J. (2022). Systematic review of policies and interventions to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace in order to prevent depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13278. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, W. W., Armenian, H., Gallo, J., Pratt, L., & Ford, D. E. (1996). Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes: A prospective population-based study. Diabetes Care, 19(10), 1097-1102. [CrossRef]

- Ferketich, A. K., Schwartzbaum, J. A., Frid, D. J., & Moeschberger, M. L. (2000). Depression as an antecedent to heart disease among women and men in the NHANES I study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(9), 1261-1268. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L. F. (1996). Sexual harassment: The definition and measurement of a construct. In M. A. Paludi (Ed.), Sexual harassment on college campuses: Abusing the ivory power (pp. 21-44). New York: State University of NY Press.

- Graham, E. A., Deschênes, S. S., Khalil, M. N., Danna, S., Filion, K. B., & Schmitz, N. (2020). Measures of depression and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 224-232. [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, K. P., Murray, V., Stokes, N., & Thurston, R. C. (2021). Sexual violence and cardiovascular disease risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas, 153, 48-60. [CrossRef]

- LoConte, N. K., Brewster, A. M., Kaur, J. S., Merrill, J. K., & Alberg, A. J. (2018). Alcohol and cancer: A statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Journal of clinical oncology, 36(1), 83-93. [CrossRef]

- Magley, V. J., Hulin, C. L., Fitzgerald, L. F., & DeNardo, M. (1999). Outcomes of self-labeling sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 390-402. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=10380419.

- Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1990). Control or defense? Depression and the sense of control over good and bad outcomes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 71-86.

- Prakash, K.C., Madsen, I.E.H., Rugulies,R., Xu, T., Westerlund, H., Nyberg, A., Kivimaki,M., & Hanson, L.L.M. (2024) Exposure to workplace sexual harassment and risk of cardiometabolic disease: a prospective cohort study of 88,904 Swedish men and women. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 31:1633-1642.

- Pratt, L. A., Ford, D. E., Crum, R. M., Armenian, H. K., Gallo, J. J., & Eaton, W. W. (1996). Depression, psychotropic medication, and risk of myocardial infarction. Circulation, 94(12), 3123-3129. [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J., Gmel Sr, G. E., Gmel, G., Hasan, O. S. M., Imtiaz, S., Popova, S.,... Shuper, P. A. (2017). The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease—an update. Addiction, 112(6), 968-1001. [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J., & Shield, k. D. (2013). Global alcohol-attributable deaths From cancer, liver cirrhosis, and injury in 2010. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 35(2), 174-183. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=104045430&site=ehost-live.

- Richman, J. A., Shinsako, S. A., Rospenda, K. M., Flaherty, J. A., & Freels, S. (2002). Workplace harassment/abuse and alcohol-related outcomes: The mediating role of psychological distress. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(4), 412-419. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12160099.

- Rospenda, K. M., Fujishiro, K., McGinley, M., Wolff, J. M., & Richman, J. A. (2017). Effects of workplace generalized and sexual harassment on abusive drinking among first year male and female college students: Does prior drinking experience matter? Substance Use & Misuse, 52(7), 892-904. [CrossRef]

- Rospenda, K. M., Richman, J. A., & Shannon, C. A. (2009). Prevalence and mental health correlates of harassment and discrimination in the workplace: Results from a national study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(5), 819-843. [CrossRef]

- Rugulies, R., Sorensen, K., ALdrich, P.T., Folker, A.P., Frilborg, M.K., Kjaer, S., Nielsen, M.B.D., Sorensen, J.K., & Madsen, I.E.H. (2020). Onset of workplace sexual harassment and subsequent depressive symptoms and incident depressive disorder in the Danish workforce. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277:21-29.

- Thurston, R. C., Chang, Y., Matthews, K. A., Von Känel, R., & Koenen, K. (2019). Association of sexual harassment and sexual assault with midlife women’s mental and physical health. JAMA internal medicine, 179(1), 48-53.

- Wasti, S. A., Bergman, M. E., Glomb, T. M., & Drasgow, F. (2000). Test of the cross-cultural generalizability of a model of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 766-778.

- Williams, D. R. (2018). Stress and the mental health of populations of color: Advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(4), 466-485.

- Willness, C. R., Steel, P., & Lee, K. (2007). A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology, 60(1), 127-162. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Characteristics of Analysis Sample and Sample Excluded from Analysis at Baseline of the Study (1996-1997).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Analysis Sample and Sample Excluded from Analysis at Baseline of the Study (1996-1997).

| Baseline Variables |

Analysis Sample (N=488) |

Excluded (N=2,004) |

| |

|

n |

% |

|

|

N |

n |

% |

|

|

| Age |

<=30 |

130 |

26.6 |

|

|

|

500 |

25.6 |

|

|

| |

31 – 40 |

167 |

34.2 |

|

|

|

573 |

29.3 |

|

|

| |

41 - 50 |

128 |

26.3 |

|

|

|

413 |

21.2 |

|

|

| |

>50 |

63 |

12.9 |

|

|

|

467 |

23.9 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

1953 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gender |

Female |

275 |

56.3 |

|

|

|

1062 |

53.0 |

|

|

| |

Male |

213 |

43.7 |

|

|

|

942 |

47.0 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

2004 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Race |

White |

328 |

67.2 |

|

|

|

960 |

48.0 |

|

|

| |

Black |

73 |

15.0 |

|

|

|

470 |

23.5 |

|

|

| |

Hispanic |

23 |

4.7 |

|

|

|

169 |

8.5 |

|

|

| |

Asian |

58 |

11.9 |

|

|

|

353 |

17.6 |

|

|

| |

Other |

6 |

1.2 |

|

|

|

49 |

2.4 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

2001 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Occupational group |

Faculty |

75 |

15.4 |

|

|

|

482 |

24.0 |

|

|

| |

Graduate Students |

196 |

40.1 |

|

|

|

569 |

28.4 |

|

|

| |

Clerical/

Administrative |

180 |

36.9 |

|

|

|

695 |

34.7 |

|

|

| |

Service/

Maintenance |

37 |

7.6 |

|

|

|

258 |

12.9 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

2004 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Mean |

SD |

min |

max |

|

Mean |

SD |

min |

max |

| Age |

years |

38.3 |

9.6 |

22 |

68 |

1953 |

40.8 |

12.0 |

20 |

86 |

| Sexual Harassment (SEQ) |

scale 19 to 57 |

21.3 |

3.9 |

19 |

45 |

1777 |

21.0 |

3.8 |

19 |

57 |

| Depression (DEPR) |

selected items 0 to 21 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

0 |

21 |

1860 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

0 |

21 |

| Drinks per day (DRINKS) |

0=none to 7=more than 6 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

0 |

7 |

1902 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1 |

7 |

Table 2.

Proportional Hazards Multiple Regression Models for First Chronic Disease Diagnosis (asthma, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular or arthritic disease) Adjusted for Current Age (>=40, >=50) and Occupation at Baseline (N=488; 269 events, 219 right-censored; 23 years followup).

Table 2.

Proportional Hazards Multiple Regression Models for First Chronic Disease Diagnosis (asthma, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular or arthritic disease) Adjusted for Current Age (>=40, >=50) and Occupation at Baseline (N=488; 269 events, 219 right-censored; 23 years followup).

| |

HR |

p-value |

| Model 1: |

|

|

| SEQ at Baseline1

|

1.038 |

.0133 |

| Model 2: |

|

|

| SEQ at Baseline1

|

1.031 |

.0463 |

| DEPR at Baseline2

|

1.049 |

.0047 |

| Model 3: |

|

|

| SEQ at Baseline1

|

1.031 |

.0475 |

| DEPR at Baseline2

|

1.041 |

.0177 |

| DRINKS previous year3

|

1.127 |

.0131 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).