Submitted:

02 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

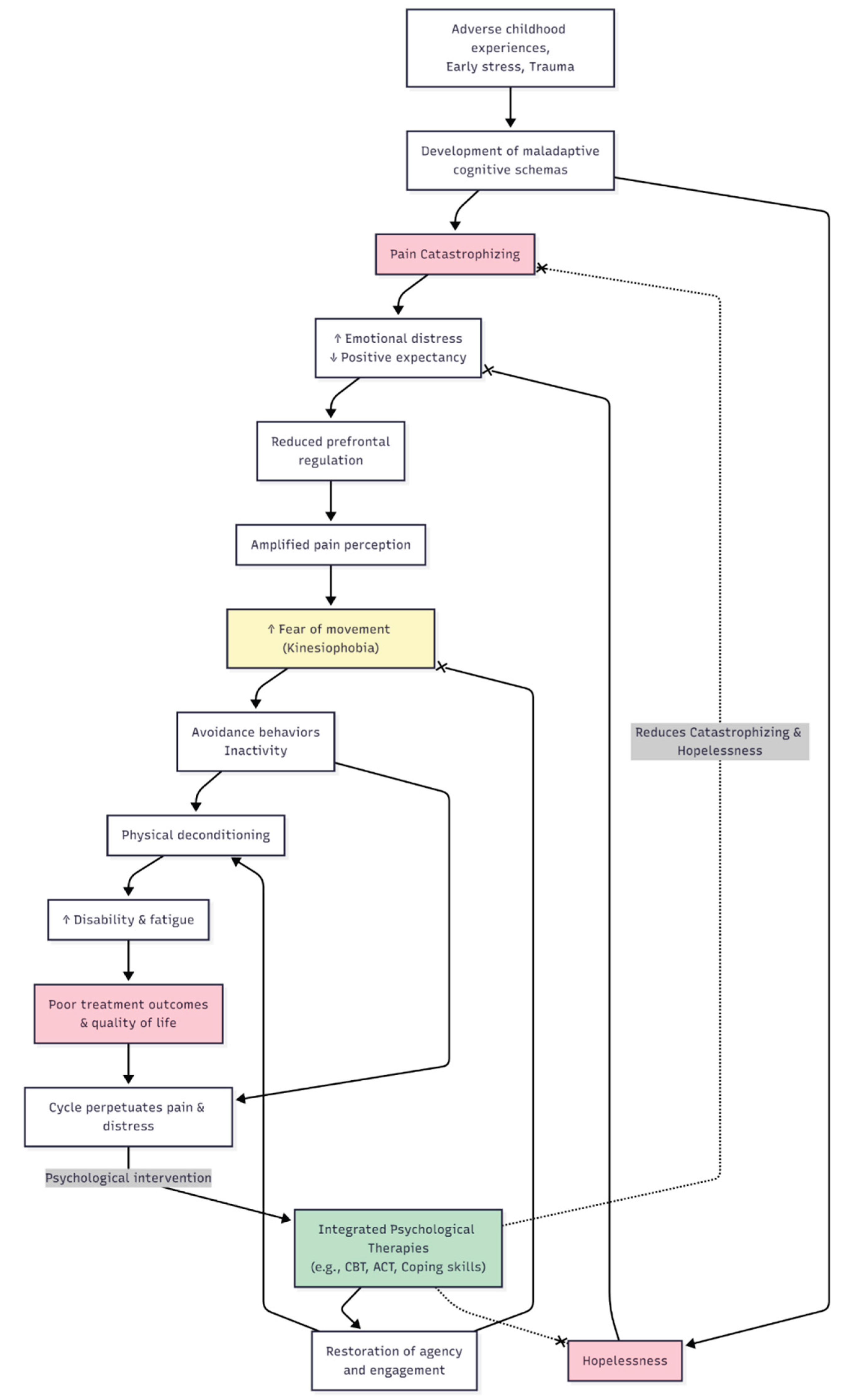

Keywords:

1. Introduction

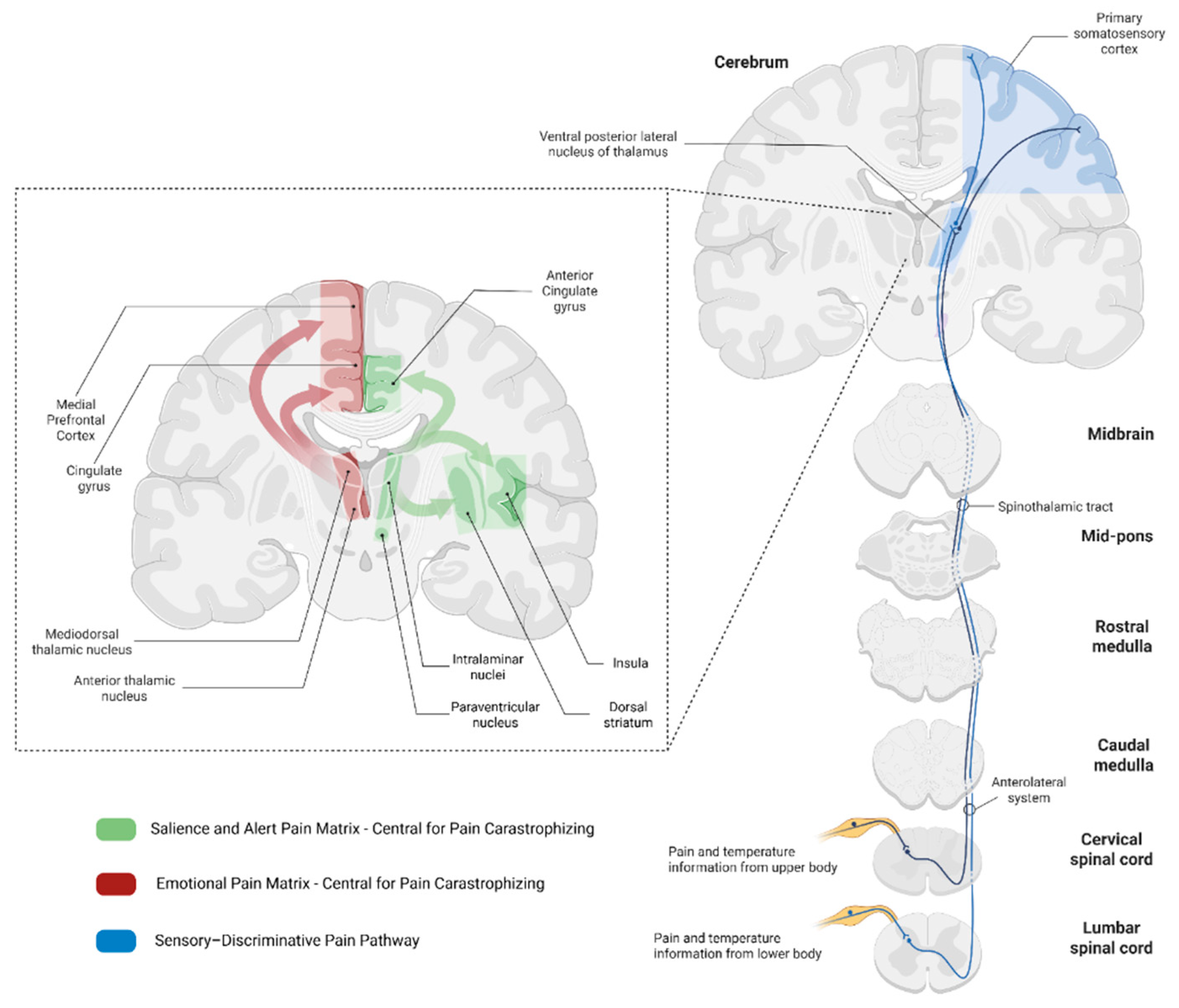

2. Neurobiological Connection Between Pain Catastrophizing and Hopelessness

3. Pain Catastrophizing in Rheumatic Diseases

4. Hopelessness in Rheumatic Diseases

5. Psychological and Developmental Origins

6. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC ACT ACR axSpA BMI CBT FM HPA OA PC PFC PsA QoL RA SLE |

Anterior Cingulate Cortex Acceptance and Commitment Therapy American College of Rheumatology Axial Spondyloarthritis Body Mass Index Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Fibromyalgia Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (axis) Osteoarthritis Pain Catastrophizing Prefrontal Cortex Psoriatic Arthritis Quality of Life Rheumatoid Arthritis Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

References

- Edwards RR, Calahan C, Mensing G, et al. Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:216–24. [CrossRef]

- Edwards RR, Bingham CO, Bathon J, et al. Catastrophizing and pain in arthritis, fibromyalgia, and other rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:325–32. [CrossRef]

- Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:745–58.

- Cohen EM, Edwards RR, Bingham CO, et al. Pain and Catastrophizing in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Observational Cohort Study. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:232–6. [CrossRef]

- Currado D, Biaggi A, Pilato A, et al. The negative impact of pain catastrophising on disease activity: analyses of data derived from patient-reported outcomes in psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023;41:1856–61. [CrossRef]

- Wilk M, Zimba O, Haugeberg G, et al. Pain catastrophizing in rheumatic diseases: prevalence, origin, and implications. Rheumatol Int. 2024;44:985–1002. [CrossRef]

- Galambos A, Szabó E, Nagy Z, et al. A systematic review of structural and functional MRI studies on pain catastrophizing. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1155–78. [CrossRef]

- Büchel, C. The role of expectations, control and reward in the development of pain persistence based on a unified model. Elife. 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Wang C, Zhou J, et al. Contribution of resting-state functional connectivity of the subgenual anterior cingulate to prediction of antidepressant efficacy in patients with major depressive disorder. Translational Psychiatry 2024 14:1. 2024;14:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Höflich A, Michenthaler P, Kasper S, et al. Circuit Mechanisms of Reward, Anhedonia, and Depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;22:105–18. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calderon J, Flores-Cortes M, Morales-Asencio JM, et al. Pain Catastrophizing, Opioid Misuse, Opioid Use, and Opioid Dose in People With Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review. Journal of Pain. 2021;22:879–91. [CrossRef]

- Nagy Z, Szigedi E, Takács S, et al. The Effectiveness of Psychological Interventions for Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life (Basel). 2023;13. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi K, Morishima T, Ikemoto T, et al. Pain Catastrophizing Is Independently Associated with Quality of Life in Patients with Severe Hip Osteoarthritis. Pain Medicine (United States). 2019;20:2220–7. [CrossRef]

- Hidaka R, Tanaka T, Hashikura K, et al. Association of high kinesiophobia and pain catastrophizing with quality of life in severe hip osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24. [CrossRef]

- Reine S, Xi Y, Archer H, et al. Effects of Depression, Anxiety, and Pain Catastrophizing on Total Hip Arthroplasty Patient Activity Level. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2023;38:1110–4. [CrossRef]

- Wood TJ, Gazendam AM, Kabali CB, et al. Postoperative Outcomes Following Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in Patients with Pain Catastrophizing, Anxiety, or Depression. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2021;36:1908–14. [CrossRef]

- Hardy A, Sandiford MH, Menigaux C, et al. Pain catastrophizing and pre-operative psychological state are predictive of chronic pain after joint arthroplasty of the hip, knee or shoulder: results of a prospective, comparative study at one year follow-up. Int Orthop. 2022;46:2461–9. [CrossRef]

- Matsuo H, Kubota M, Naruse H, et al. Association of knee joint performance and gait patterns with pain catastrophizing in patients with severe knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2025;26. [CrossRef]

- Reddy RS, Tedla JS, Alshehri SHS, et al. Associations between transcranial direct current stimulation session exposure and clinical outcomes in knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional analysis exploring the role of pain catastrophizing. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20. [CrossRef]

- Vela J, Dreyer L, Petersen KK, et al. Quantitative sensory testing, psychological profiles and clinical pain in patients with psoriatic arthritis and hand osteoarthritis experiencing pain of at least moderate intensity. Eur J Pain. 2024;28:310–21. [CrossRef]

- Wilk M, Pripp AH, Korkosz M, et al. Exploring pain catastrophizing and its associations with low disease activity in rheumatic inflammatory disorders. Rheumatol Int. 2023;43:687–94. [CrossRef]

- Currado D, Saracino F, Ruscitti P, et al. Pain catastrophizing negatively impacts drug retention rate in patients with Psoriatic Arthritis and axial Spondyloarthritis: results from a 2-years perspective multicenter GIRRCS (Gruppo Italiano di Ricerca in Reumatologia Clinica) study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2024;26. [CrossRef]

- Wilk M, Łosińska K, Pripp AH, et al. Pain catastrophizing in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: biopsychosocial perspective and impact on health-related quality of life. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42:669–82. [CrossRef]

- Tekaya A Ben, Said H Ben, Yousfi I, et al. Burden of disease, pain catastrophizing, and central sensitization in relation to work-related issues in young spondyloarthritis patients. Reumatologia. 2024;62:35–42. [CrossRef]

- Gazik AB, Vagharseyyedin SA, Saremi Z, et al. Severity of Pain Catastrophizing and Its Associations With Cognitive Flexibility and Self-Efficacy in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2024;22:e1923. [CrossRef]

- Alcon C, Bergman E, Humphrey J, et al. The Relationship between Pain Catastrophizing and Cognitive Function in Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Scoping Review. Pain Res Manag. 2023;2023. [CrossRef]

- Karaca NB, Arin-Bal G, Sezer S, et al. Physical Activity, Kinesiophobia, Pain Catastrophizing, Body Awareness, Depression and Disease Activity in Patients With Ankylosing Spondylitis and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Explorative Study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2024;22. [CrossRef]

- Lööf H, Demmelmaier I, Henriksson EW, et al. Fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44:93–9. [CrossRef]

- Edwards RR, Goble L, Kwan A, et al. Catastrophizing, pain, and social adjustment in scleroderma: Relationships with educational level. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2006;22:639–46. [CrossRef]

- Bearzi P, Navarini L, Mattioli LC, et al. Hopelessness is associated to severity of both digital vasculopathy and lung disease in systemic sclerosis patients: a prospective one-year study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2025;43:1508–15. [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, N. Comparison of kinesiophobia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27:11508–16. [CrossRef]

- Kinikli GI, Bal GA, Aydemir-Guloksuz EG, et al. Predictors of pain catastrophizing in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2022;68:1247–51. [CrossRef]

- Bağlan Yentür S, Karatay S, Oskay D, et al. Kinesiophobia and related factors in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Turk J Med Sci. 2019;49:1324–31. [CrossRef]

- Segal BM, Pogatchnik B, Rhodus N, et al. Pain in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: The role of catastrophizing and negative illness perceptions. Scand J Rheumatol. 2014;43:234–41. [CrossRef]

- Gebreegziabher EA, Bunya VY, Baer AN, et al. Neuropathic Pain in the Eyes, Body, and Mouth: Insights from the Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance. Pain Pract. 2021;21:630–7. [CrossRef]

- Apriliyasari RW, Chou CW, Tsai PS. Pain Catastrophizing as a Mediator Between Pain Self-Efficacy and Disease Severity in Patients with Fibromyalgia. Pain Management Nursing. 2023;24:622–6. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca Das Neves J, Serra E, Kosinski T, et al. Catastrophizing and rumination mediate the link between functional disabilities and anxiety/depression in fibromyalgia. A double-mediation model. Encephale. 2024;50:162–9. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Mampel J, Bautista IJ, Salvat I, et al. Dry needling in people with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial of its effects on pain sensitivity and pain catastrophizing influence. PM&R. 2025;17:419–30. [CrossRef]

- Varallo G, Scarpina F, Arnison T, et al. Suicidal ideation in female individuals with fibromyalgia and comorbid obesity: prevalence and association with clinical, pain-related, and psychological factors. Pain Medicine. 2024;25:239–47. [CrossRef]

- Serafini G, Lamis DA, Aguglia A, et al. Hopelessness and its correlates with clinical outcomes in an outpatient setting. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:472–9. [CrossRef]

- Sipilä R, Kalso E, Kemp H, et al. Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors. Scand J Pain. 2024;24. [CrossRef]

- Pinto AJ, Roschel H, de Sá Pinto AL, et al. Physical inactivity and sedentary behavior: Overlooked risk factors in autoimmune rheumatic diseases? Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:667–74.

- Mok CC, Ko GTC, Ho LY, et al. Prevalence of atherosclerotic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in patients with chronic inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:195–202. [CrossRef]

- Feld J, Nissan S, Eder L, et al. Increased Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome and Adipocytokine Levels in a Psoriatic Arthritis Cohort. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2018;24:302–7. [CrossRef]

- Mallbris L, Ritchlin CT, Ståhle M. Metabolic disorders in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8:355–63.

- Azfar RS, Gelfand JM. Psoriasis and metabolic disease: Epidemiology and pathophysiology. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:416–22.

- Betancur G, Orozco MC, Schneeberger E, et al. Prevalence of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome in Patients with Axial Spondyloarthritis - ACR Meeting Abstracts. 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. 2015. https://acrabstracts. 6 September.

- Goodwin B, Khan D, Mehta A, et al. Exercise Therapies for Fibromyalgia Pain Catastrophizing: A Systematic Review and Comparative Analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2025;27. [CrossRef]

- Estévez-López F, Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Segura-Jiménez V, et al. The discordance between subjectively and objectively measured physical function in women with fibromyalgia: association with catastrophizing and self-efficacy cognitions. The al-Ándalus project. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:329–37. [CrossRef]

- Woolf, CJ. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152:S2.

- Angst F, Lehmann S, Sandor PS, et al. Catastrophizing as a prognostic factor for pain and physical function in the multidisciplinary rehabilitation of fibromyalgia and low back pain. European Journal of Pain (United Kingdom). 2022;26:1569–80. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).