Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

DNA Extraction

2.2. Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Features

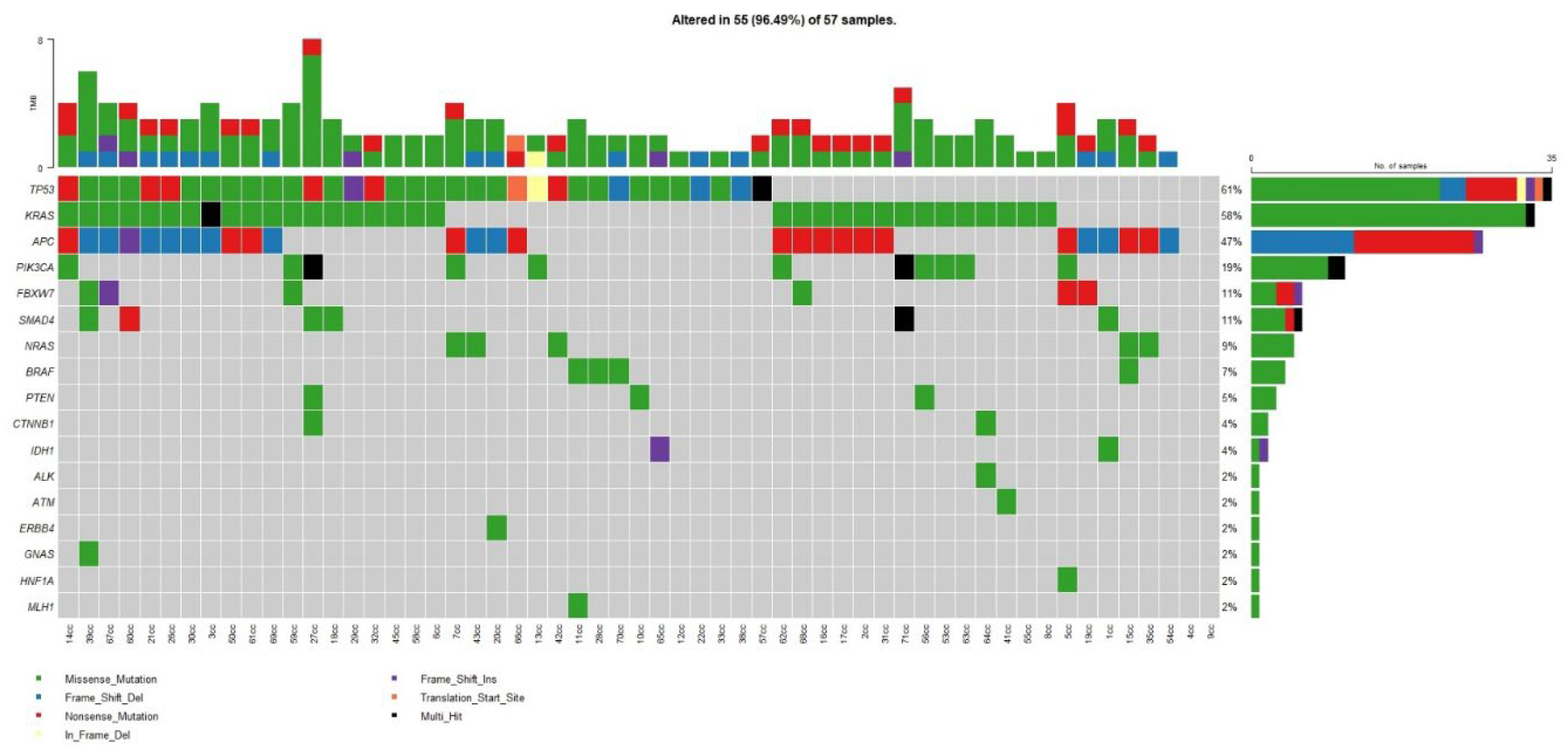

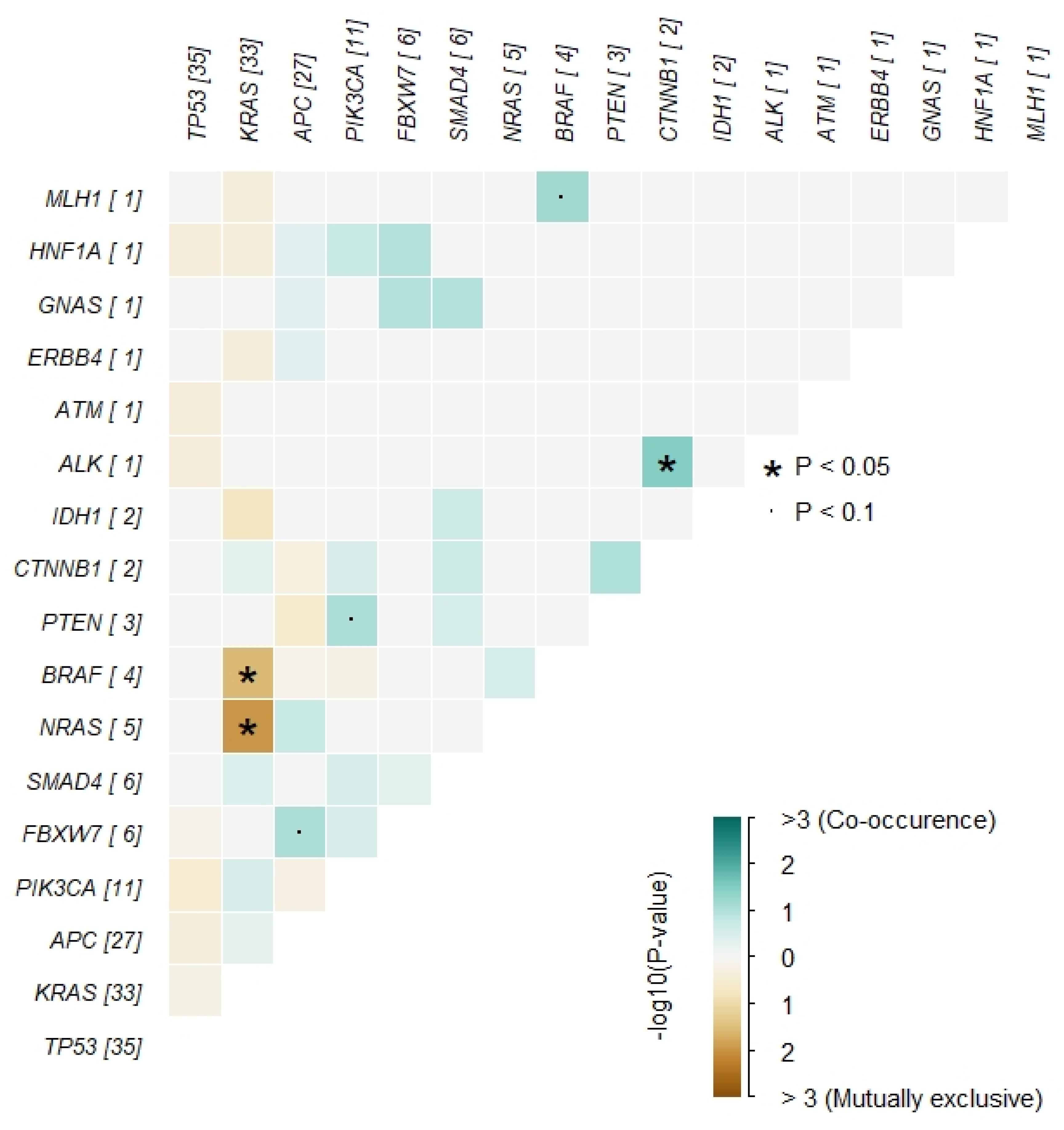

3.2. Somatic Mutations in the Whole Cohort

3.3. Mutations by Age Group

3.4. Mutations and Prognosis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Question Is—Does This Matter for Patient’s Management?

4.2. Targeting the CIN Pathway

4.3. Targeting the MSI Pathway

4.4. Targeting the CIMP Pathway

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Compliance

References

- Baidoun, F.; Elshiwy, K.; Elkeraie, Y.; Merjaneh, Z.; Khoudari, G.; Sarmini, M.T.; Gad, M.; Al-Husseini, M.; Saad, A. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Recent Trends and Impact on Outcomes. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakrishnan, T.; Ng, K. Early-Onset Gastrointestinal Cancers. JAMA 2025, 334, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REACCT Collaborative; Zaborowski, A.M.; Abdile, A.; Adamina, M.; Aigner, F.; D’allens, L.; Allmer, C.; Álvarez, A.; Anula, R.; Andric, M.; et al. Characteristics of Early-Onset vs Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 865–874. [CrossRef]

- Spaander, M.C.W.; Zauber, A.G.; Syngal, S.; Blaser, M.J.; Sung, J.J.; You, Y.N.; Kuipers, E.J. Young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2023, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, B.; Riccò, B.; Caffari, E.; Zaniboni, S.; Salati, M.; Spallanzani, A.; Garajovà, I.; Benatti, S.; Chiavelli, C.; Dominici, M.; et al. Early Onset Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Current Insights and Clinical Management of a Rising Condition. Cancers 2023, 15, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausman, V.; Dornblaser, D.; Anand, S.; Hayes, R.B.; O'COnnell, K.; Du, M.; Liang, P.S. Risk Factors Associated With Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2752–2759.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'COnnell, J.B.; Maggard, M.A.; Liu, J.H.; Etzioni, D.A.; Livingston, E.H.; Ko, C.Y. Rates of Colon and Rectal Cancers are Increasing in Young Adults. Am. Surg. 2003, 69, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020.

- Mauri, G.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Russo, A.; Marsoni, S.; Bardelli, A.; Siena, S. Early-onset colorectal cancer in young individuals. Mol. Oncol. 2018, 13, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaander, M.C.W.; Zauber, A.G.; Syngal, S.; Blaser, M.J.; Sung, J.J.; You, Y.N.; Kuipers, E.J. Young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2023, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, V.; Bosetti, C.; Levi, F.; Polesel, J.; Zucchetto, A.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Risk factors for young-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2012, 24, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausman, V.; Dornblaser, D.; Anand, S.; Hayes, R.B.; O'COnnell, K.; Du, M.; Liang, P.S. Risk Factors Associated With Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2752–2759.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, A.N.; Su, Y.-R.; Jeon, J.; Thomas, M.; Lin, Y.; Conti, D.V.; Win, A.K.; Sakoda, L.C.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I.; Peterse, E.F.; et al. Cumulative Burden of Colorectal Cancer–Associated Genetic Variants Is More Strongly Associated With Early-Onset vs Late-Onset Cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1274–1286.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaander, M.C.W.; Zauber, A.G.; Syngal, S.; Blaser, M.J.; Sung, J.J.; You, Y.N.; Kuipers, E.J. Young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2023, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, D.; Jones, R.; Gao, J.; Sun, L.; Liao, J.; Yang, G.-Y. Unique clinicopathologic and genetic alteration features in early onset colorectal carcinoma compared with age-related colorectal carcinoma: a large cohort next generation sequence analysis. Hum. Pathol. 2020, 105, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willauer, A.N.; Liu, Y.; Pereira, A.A.L.; Lam, M.; Morris, J.S.; Raghav, K.P.S.; Morris, V.K.; Menter, D.; Broaddus, R.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer 2019, 125, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugai, T.; Haruki, K.; Harrison, T.A.; Cao, Y.; Qu, C.; Chan, A.T.; Campbell, P.T.; Akimoto, N.; Berndt, S.; Brenner, H.; et al. Molecular Characteristics of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer According to Detailed Anatomical Locations: Comparison With Later-Onset Cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 118, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponvilawan, B.; Sakornsakolpat, P.; Pongpaibul, A.; Roothumnong, E.; Akewanlop, C.; Pithukpakorn, M.; Korphaisarn, K. Comprehensive genomic analysis in sporadic early-onset colorectal adenocarcinoma patients. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T.; Fujimoto, A.; Igarashi, Y. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Public Health Strategies. Digestion 2025, 106, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, M.R.; Rosa, I.; Claro, I. Early-onset colorectal cancer: A review of current knowledge. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, A.; Carethers, J.M. EPIDEMIOLOGY AND BIOLOGY OF EARLY ONSET COLORECTAL CANCER. 2022, 21, 162–182. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Jakubowski, C.D.; Fedewa, S.A.; Davis, A.; Azad, N.S. Colorectal Cancer in the Young: Epidemiology, Prevention, Management. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2020, 40, e75–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nfonsam, V.; Wusterbarth, E.; Gong, A.; Vij, P. Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Surg. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2022, 31, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbes, S.; Baldi, S.; Sellami, H.; Amedei, A.; Keskes, L. Molecular methods for colorectal cancer screening: Progress with next-generation sequencing evolution. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2023, 15, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-K.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Chern, Y.-J.; Yu, Y.-L.; Lin, Y.-C.; Hsieh, P.-S.; Chiang, J.-M.; You, J.-F. Differences in characteristics and outcomes between early-onset colorectal cancer and late-onset colorectal cancers. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2024, 50, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakrishnan, T.; Ng, K. Early-Onset Gastrointestinal Cancers. JAMA 2025, 334, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foppa, C.; Maroli, A.; Lauricella, S.; Luberto, A.; La Raja, C.; Bunino, F.; Carvello, M.; Sacchi, M.; De Lucia, F.; Clerico, G.; et al. Different Oncologic Outcomes in Early-Onset and Late-Onset Sporadic Colorectal Cancer: A Regression Analysis on 2073 Patients. Cancers 2022, 14, 6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Spinelli, A.; Ciardiello, D.; Luc, M.R.; de Pascale, S.; Bertani, E.; Fazio, N.; Romario, U.F. Prognosis of early-onset versus late-onset sporadic colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 215, 115172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barot, S.; Liljegren, A.; Nordenvall, C.; Blom, J.; Radkiewicz, C. Incidence trends and long-term survival in early-onset colorectal cancer: a nationwide Swedish study. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, H.; Xu, S.; Hu, P.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Performance validation of an amplicon-based targeted next-generation sequencing assay and mutation profiling of 648 Chinese colorectal cancer patients. Virchows Arch. 2018, 472, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim BJ, Hanna MH. Colorectal cancer in young adults. J Surg Oncol. 2023;127(8):1231–1309.

- Alshenaifi, J.Y.; Vetere, G.; Maddalena, G.; Yousef, M.; White, M.G.; Shen, J.P.; Vilar, E.; Parseghian, C.; Dasari, A.; Morris, V.K.; et al. Mutational and co-mutational landscape of early onset colorectal cancer. Biomarkers 2025, 30, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, D.; Jones, R.; Gao, J.; Sun, L.; Liao, J.; Yang, G.-Y. Unique clinicopathologic and genetic alteration features in early onset colorectal carcinoma compared with age-related colorectal carcinoma: a large cohort next generation sequence analysis. Hum. Pathol. 2020, 105, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willauer, A.N.; Liu, Y.; Pereira, A.A.L.; Lam, M.; Morris, J.S.; Raghav, K.P.S.; Morris, V.K.; Menter, D.; Broaddus, R.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer 2019, 125, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugai, T.; Haruki, K.; Harrison, T.A.; Cao, Y.; Qu, C.; Chan, A.T.; Campbell, P.T.; Akimoto, N.; Berndt, S.; Brenner, H.; et al. Molecular Characteristics of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer According to Detailed Anatomical Locations: Comparison With Later-Onset Cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 118, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponvilawan, B.; Sakornsakolpat, P.; Pongpaibul, A.; Roothumnong, E.; Akewanlop, C.; Pithukpakorn, M.; Korphaisarn, K. Comprehensive genomic analysis in sporadic early-onset colorectal adenocarcinoma patients. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatsirisupachai K, Lagger C, de Magalhães JP. Age-associated differences in the cancer molecular landscape. Trends Cancer. 2022;8(11):962–971.Spaander MCW, Zauber AG, Syngal S. Young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):21.

- Chang, C.-C.; Lin, P.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Lan, Y.-T.; Lin, H.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Yang, S.-H.; Liang, W.-Y.; Chen, W.-S.; Jiang, J.-K.; et al. Molecular and Clinicopathological Differences by Age at the Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, C.; Oh, S.Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Suh, K.W. Differences in biological behaviors between young and elderly patients with colorectal cancer. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0218604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Morris, M.; Idrees, K.; Gimbel, M.I.; Rosenberg, S.; Zeng, Z.; Li, F.; Gan, G.; Shia, J.; LaQuaglia, M.P.; et al. Colorectal cancer in the very young: a comparative study of tumor markers, pathology and survival in early onset and adult onset patients. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 51, 1812–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.S.E.-D.; Abdel-Fattah, M.A.; Lotfy, M.M.; Nassar, A.; Abouelhoda, M.; Touny, A.O.; Hassan, Z.K.; Eldin, M.M.; Bahnassy, A.A.; Khaled, H.; et al. Multigene Panel Sequencing Reveals Cancer-Specific and Common Somatic Mutations in Colorectal Cancer Patients: An Egyptian Experience. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Lu, S.-H.; Shi, Y. Prognostic impact of mutation profiling in patients with stage II and III colon cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24310–24310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsyc, M.; Yaeger, R. Impact of somatic mutations on patterns of metastasis in colorectal cancer. 2015, 6, 645–649–649. [CrossRef]

- Kalady, M.F.; DeJulius, K.L.B.; Sanchez, J.A.; Jarrar, A.; Liu, X.; Manilich, E.; Skacel, M.; Church, J.M.M. BRAF Mutations in Colorectal Cancer Are Associated With Distinct Clinical Characteristics and Worse Prognosis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2012, 55, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Botton, S.; Mondesir, J.; Willekens, C.; Touat, M. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations as novel therapeutic targets: current perspectives. J. Blood Med. 2016, 7, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Ye, D.; Guan, K.-L.; Xiong, Y. IDH1andIDH2Mutations in Tumorigenesis: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Perspectives. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 5562–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Hossain, U.; Mandal, A.; Sil, P.C. The Wnt signaling pathway: a potential therapeutic target against cancer. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2019, 1443, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dihlmann, S.; Siermann, A.; Doeberitz, M.v.K. The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs aspirin and indomethacin attenuate β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling. Oncogene 2001, 20, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewitowicz, P.; Koziel, D.; Gluszek, S.Z.; Matykiewicz, J.; Wincewicz, A.; Horecka-Lewitowicz, A.; Nasierowska-Guttmejer, A. Is there a place for practical chemoprevention of colorectal cancer in light of COX-2 heterogeneity? Pol. J. Pathol. 2014, 4, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuynman, J.B.; Vermeulen, L.; Boon, E.M.; Kemper, K.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Richel, D.J. Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibition Inhibits c-Met Kinase Activity and Wnt Activity in Colon Cancer. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Uram, J.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Kemberling, H.; Eyring, A.D.; Skora, A.D.; Luber, B.S.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.; et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neil, B.H.; Wallmark, J.M.; Lorente, D.; Elez, E.; Raimbourg, J.; Gomez-Roca, C.; Ejadi, S.; A Piha-Paul, S.; Stein, M.N.; Razak, A.R.A.; et al. Safety and antitumor activity of the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0189848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, J.; Prewett, M.; Rockwell, P.; Goldstein, N.I. CCR 20th Anniversary Commentary: A Chimeric Antibody, C225, Inhibits EGFR Activation and Tumor Growth. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, D.J.; O'Callaghan, C.J.; Karapetis, C.S.; Zalcberg, J.R.; Tu, D.; Au, H.-J.; Berry, S.R.; Krahn, M.; Price, T.; Simes, R.J.; et al. Cetuximab for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2040–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | All patients (n=54) | ≤50 years (n=21) | >50 years (n=33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 55 (31–92) | 43 (31–50) | 63 (51–92) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 29 (54%) | 10 | 19 |

| Female | 25 (46%) | 11 | 14 |

| Stage | I: 9; II: 14; III: 17; IVA: 6; IVB: 8 | Higher proportion of advanced stages | Lower proportion of advanced stages |

| Gene | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| TP53 | 64% | 35 |

| KRAS | 60% | 33 |

| APC | 51% | 28 |

| PIK3CA | 25% | 14 |

| SMAD4 | 13% | 7 |

| NRAS | 11% | 6 |

| FBXW7 | 11% | 6 |

| BRAF | 7% | 4 |

| Gene | ≤50 years (n=21) |

|---|---|

| TP53 | 16 (76%) |

| APC | 12 (57%) |

| KRAS | 9 (43%) |

| NRAS | 6 (29%) |

| PIK3CA | 3 (14%) |

| SMAD4 | 2 (9%) |

| FBXW7 | 1 (5%) |

| Other (HNF1A, ERBB4, PTEN, BRAF, CTNNB1, ALK, IDH1, GNAS, ATM) | sporadic |

| Gene | Better prognosis (Stage I–II) | Worse prognosis (Stage III–IVB) |

|---|---|---|

| TP53 | 13 | 23 |

| KRAS | 17 | 15 |

| APC | 16 | 13 |

| PIK3CA | 9 | 6 |

| NRAS | 2 | 4 |

| IDH1 | 2 | 0 |

| CTBX1 | 2 | 0 |

| HNF1A | 1 | 0 |

| ALK | 1 | 0 |

| ERBB4 | 0 | 1 |

| GNAS | 0 | 1 |

| ATM | 0 | 1 |

| Others (FBXW7, SMAD4, BRAF, PTEN) | similar frequencies across groups |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).