1. Introduction

3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) is a new psychoactive substance (NPS), belonging to the class of synthetic cathinones, which is structurally related to pyrovalerone and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) [

1,

2]. MDPV acts primarily as a potent dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE) transporter (DAT and NET, respectively) blocker, with negligible activity at the serotonin transporter (SERT) [

1,

3]. This pharmacodynamic profile leads to strong psychostimulant and euphoric effects through increased synaptic concentrations of catecholamines, particularly DA. Such increase in specific brain subregions (i.e. nucleus accumbens) explains its high abuse potential and reinforcing properties [

4]. Moreover, its pharmacological mechanism of action as DA and NE reuptake inhibitor also underlie other adverse physiological consequences, including severe agitation, hypertension, hyperthermia, seizures, and cardiac arrhythmias [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Since its emergence as a recreational drug, MDPV has been implicated in numerous cases of acute intoxication and death [

5,

8,

9]. Despite these alarming reports, the precise mechanisms by which MDPV induces cardiotoxic effects remain not fully understood.

The cardiovascular system is particularly vulnerable to psychostimulants that enhance catecholaminergic activity. Increased sympathetic drive and catecholamine release can result in vasoconstriction, hypertension, tachycardia, arrhythmias, and, in severe cases, cardiac arrest [

1,

10]. In humans and mammalian models, these compounds often induce pronounced hyperthermia, which further elevates metabolic demand, disrupts electrolyte homeostasis, and predisposes individuals to rhythm disturbances and cardiac failure [

11]. The presence of hyperthermia thus constitutes a major confounding factor when assessing the direct cardiotoxic effects of synthetic cathinones. However, specific data regarding the direct impact of MDPV’s on cardiac function remain scarce [

7,

12], underscoring the need for more comprehensive studies to elucidate its cardiotoxic potential.

Zebrafish (

Danio rerio) has emerged as a highly relevant model organism for investigating the molecular and physiological effects of neuroactive and cardiotoxic compounds. Zebrafish embryos and larvae offer a unique combination of advantages for toxicological research: rapid external development, optical transparency, high genetic and physiological homology with mammals, and well-characterized behavioral and cardiovascular phenotypes [

13,

14]. The zebrafish heart shares remarkable structural and electrophysiological similarities with the human heart, including the presence of nodal tissue and comparable ion channel expression patterns [

15]. Furthermore, its early-stage transparency allows for real-time, non-invasive visualization of cardiac function, such as heart rate, rhythm, and conduction, facilitating the detection of arrhythmias and other functional abnormalities

in vivo [

16,

17,

18]. Moreover, unlike homeothermic mammalian species, zebrafish are poikilothermic and therefore do not develop drug-induced hyperthermia or thermoregulatory feedback responses. This allows for direct evaluation of a compound’s effects on cardiac and neural function under controlled thermal conditions, eliminating one of the main confounding factors present in traditional models of stimulant toxicity [

19]. Finally, at 5 days post-fertilization (dpf), zebrafish embryos exhibit quantifiable patterns of spontaneous locomotor activity that are modulated by neuroactive substances, making them an excellent system for evaluating psychotropic or neurotoxic effects.

In this context, zebrafish provide a powerful integrative model to assess multiple endpoints of MDPV toxicity—from cardiac physiology to neurobehavioral outcomes and molecular responses—within a unified experimental framework. Previous research on synthetic cathinones in zebrafish has primarily focused on behavioral alterations [

20,

21] or general developmental toxicity [

22], whereas the combined analysis of cardiotoxicity, neurobehavioral, and transcriptional effects remains relatively unexplored. Such integrative approaches are essential to understand how MDPV simultaneously affects neural and cardiac systems and to identify early molecular signatures of its toxic action.

The present study aimed to provide a comprehensive assessment of MDPV toxicity in zebrafish embryos and larvae by integrating physiological, behavioral, and molecular endpoints. First, acute cardiotoxicity and lethality were evaluated in 3 dpf to determine the concentration-dependent effects of MDPV on heart rate, atrioventricular conduction, and ventricular mechanical performance, including fractional shortening (FS), stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF), and cardiac output (CO). Neurobehavioral effects were subsequently investigated by quantifying basal locomotor activity at 5 dpf and sensorimotor gating through prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle response (ASR) at 7 dpf, a developmental stage at which dopaminergic modulation of startle behavior is functionally established [

23]. Finally, the transcriptional response of a panel of early-response genes involved in dopaminergic signaling, stress response and neuronal activation was analyzed following short-term MDPV exposure to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying its behavioral and physiological effects.

Together, these complementary approaches provide an integrated evaluation of the cardiotoxic and neurobehavioral consequences of acute MDPV exposure in zebrafish and identify key molecular pathways associated with its psychostimulant-like activity and developmental toxicity. By comparing the effective concentrations producing locomotor suppression and atrioventricular conduction block, the study also defines an approximate functional safety margin between neurobehavioral and cardiotoxic effects, thereby refining the toxicodynamic profile of MDPV.

2. Results

2.1. Lethality Test

After 24 h of exposure, MDPV induced a clear concentration-dependent increase in lethality in 3 dpf zebrafish embryos (

Supplementary Figure S1). At 540 and 600 µM, mortality reached 100%, while concentrations of 420 and 480 µM resulted in lethality over 85% (individual data are available at Supplementary Dataset 1).

Dose–response fitting using a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model constrained between 0 and 100% lethality confirmed the steep concentration dependence of MDPV-induced mortality. The model yielded an LC₅₀ of 343.8 µM (95% bootstrap CI: 318.1–369.4 µM) and a Hill slope of 9.81 (95% CI: 6.75–10.00), indicating an abrupt transition between sublethal and lethal concentrations.

These results demonstrate that MDPV exerts a potent, sharply concentration-dependent lethality in zebrafish embryos following 24 h of exposure, with complete mortality observed from 540 µM upward.

2.2. Cardiotoxicity Assessment

2.2.1. Chronotropic and Conduction Effects of MDPV

Figure 1 shows the main effects of 2 h waterborne exposure to 60-480 mM MDPV on the beat frequency of the atrium and ventricle of 3 dpf embryos (individual data are available at Supplementary Dataset 2). A mixed repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of heart chamber (

F(1,174) = 642.42,

p = 2.65 × 10⁻⁶⁰,

ηp² = 0.79), MDPV concentration [

F(4,174) = 355.21,

p = 1.54 × 10⁻⁸²,

ηp² = 0.89], and their interaction [

F(4,174) = 122.91,

p = 1.32 × 10⁻⁴⁹,

ηp² = 0.74] on normalized beat frequencies.

Control embryos, exhibited the expected 1:1 atrioventricular (AV) conduction pattern (

Figure 2 MDPV induced a concentration-dependent disruption of this synchrony. At 60 µM, cardiac rhythm slowed without loss of coordination, indicating a predominantly chronotropic effect. From 120 µM onward, ventricular contractions became progressively dissociated from the atrial rhythm, giving rise to 2:1 AV block that advanced to higher-degree block at 240–480 µM.

Post-hoc comparisons confirmed that all concentrations significantly reduced atrial beat frequency relative to controls (all p < 0.001), whereas ventricular rate exhibited a much steeper decline, with 480 µM producing near-complete suppression of ventricular activity (92% reduction vs. control, p < 0.001). These differential responses account for the marked interaction effect and demonstrate preferential vulnerability of ventricular conduction to MDPV.

To quantify the onset of conduction failure, the atrioventricular conduction ratio was converted into % AV block using % block = 100 × (1 − 1/R), where R = AV ratio. A logistic concentration–response model (

Supplementary Figure S2) revealed a monotonic increase in AV block with an EC₅₀ of 228.3 µM (95% bootstrap CI: 208.1–253.3 µM; Hill slope 1.45). This parameter defines the midpoint of the transition from rhythmic entrainment to high-degree AV block, confirming that MDPV induces a sharp, concentration-dependent collapse of ventricular conduction at high micromolar levels.

Together, these findings demonstrate that MDPV causes dose-dependent bradycardia driven by preferential suppression of ventricular excitability, culminating in complete AV block at the highest concentrations tested.

2.2.2. Mechanical Cardiac Performance

To further characterize the cardiac effects of MDPV, quantitative analysis of ventricular motion was performed to determine fractional shortening (FS), stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF), and cardiac output (CO) in 3 dpf zebrafish embryos after a 2 h exposure to 120–480 µM MDPV (

Figure 3). These parameters provide integrated measures of ventricular contractility and overall pump performance (individual data are available at Supplementary Dataset 3).

MDPV exposure produced a concentration-dependent decline in overall cardiac function. A one-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of treatment on CO (F(3, 39) = 67.6, p = 1.6 × 10⁻¹⁵) and EF (F(3, 39) = 6.9, p = 7.8 × 10⁻⁴), whereas effects on SV and FS were less pronounced. Post hoc Dunnett comparisons against controls confirmed that CO was significantly reduced at all tested MDPV concentrations (p < 0.001 for all), while EF was only significantly decreased at 480 µM (p < 0.01). FS and SV values did not differ significantly from controls (all p > 0.05).

The observed reduction in CO closely paralleled the concentration-dependent bradycardia and progressive atrioventricular conduction block described above, indicating that MDPV primarily affects cardiac performance through chronotropic and conduction mechanisms. The significant decrease in EF at 480 µM suggests an additional contractile impairment emerging at higher concentrations. These results demonstrate that MDPV exerts concentration-dependent negative chronotropic and, at high concentrations, inotropic effects in zebrafish embryos, leading to substantial reductions in overall cardiac output.

2.3. Behavioral Assessment

2.3.1. Basal Locomotor Activity

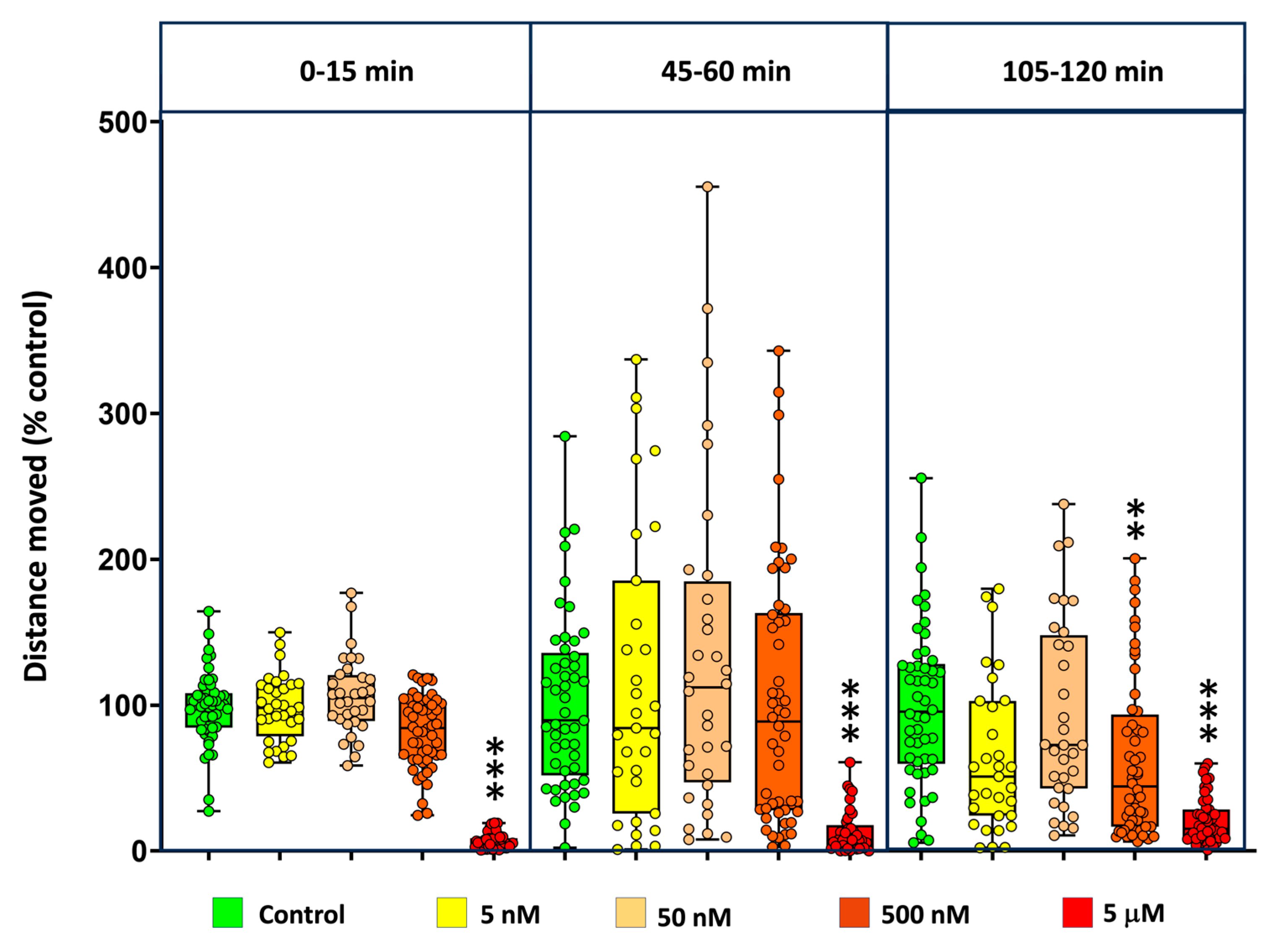

Basal locomotor activity (BLA) was assessed in 5 dpf zebrafish embryos exposed to a range of concentrations from 5 nM to 5 mM MDPV. Locomotor behavior was recorded during three 15-min observation windows: 0–15 min, 45–60 min, and 105–120 min after the onset of exposure. Individual data are available at Supplementary Dataset 4.

As shown in

Figure 4, MDPV exposure induced a concentration-dependent decrease in BLA relative to controls. The effect was particularly evident at the highest concentration tested (5 µM), where activity was significantly reduced in all three periods analyzed. Kruskal–Wallis analyses confirmed significant treatment effects for each observation window: 0–15 min [

H(4) = 127.4,

p < 0.001], 45–60 min [

H(4) = 50.18,

p < 0.001], and 105–120 min [

H(4) = 54.90,

p < 0.001]. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that at the last observation window (105-120 min), only the 0.5 µM and 5 µM groups differed significantly from the control (p < 0.05), whereas lower concentrations (0.005 and 0.05 µM) had no detectable effect.

To further characterize the concentration–response relationship, replicate-level data from the 105–120 min interval were fitted to a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model. As shown in

Supplementary Figure S3, the best-fit curve described a monotonic, sigmoidal inhibition of locomotor activity, with an estimated EC₅₀ of 2.51 µM (95 % bootstrap CI: 0.38–5.08 µM) and a Hill slope of −0.98. The top and bottom plateaus of the curve corresponded to approximately 80.7 % and 7.3 % of control activity, respectively, while the calculated EC₁₀ and EC₉₀ were 0.27 µM and 23.4 µM. These quantitative results are consistent with the nonparametric analyses, confirming that MDPV produces a concentration-dependent and sustained suppression of locomotor behavior, with half-maximal inhibition occurring at low micromolar concentrations.

2.3.2. Prepulse Inhibition

The disruptive effects of amphetamine-type stimulants on prepulse inhibition (PPI) are well established in mammals and humans, where they are mediated by dopaminergic activation of D₂ receptors. However, to our knowledge, the effects of amphetamine-like psychostimulants on PPI have not yet been investigated in zebrafish. Therefore, dextroamphetamine was first used as a reference compound to validate the assay before assessing the potential effects of MDPV.

As shown in

Supplementary Figure S4, exposure of 7 dpf zebrafish larvae to 5 µM dextroamphetamine for 30 min produced a robust increase in PPI relative to controls at both 50 ms and 500 ms prepulse–pulse intervals. To confirm the dopaminergic basis of this effect, co-exposure with the D₂ receptor antagonist haloperidol (0.5 µM) was performed, which completely prevented the enhancement of PPI induced by dextroamphetamine, restoring responses to control levels.

In the 50 ms interval, the median (IQR) PPI values were 80.0 % (71.4–100.0) in controls, 100.0 % (100.0–100.0) in dextroamphetamine-treated larvae, and 77.8 % (55.6–87.5) in the haloperidol co-treated group. In the 500-ms interval, the corresponding values were 77.1 % (61.5–81.5), 100.0 % (86.1–100.0), and 50.0 % (33.3–77.8), respectively. Statistical analysis confirmed significant differences among the experimental groups [50 ms interval: H(2) = 27.93, p = 8.4 × 10⁻⁷; 500 ms interval: H(2) = 34.06, p = 4.0 × 10⁻⁸]. These results demonstrate that dextroamphetamine exposure enhances PPI in zebrafish larvae and that this effect is mediated by D₂ receptors.

In contrast, MDPV exposure did not significantly alter PPI. In the 50 ms interval, median (IQR) PPI values were 80.0 % (63.9–100.0) in controls, 79.2 % (61.3–100.0) in 5 nM MDPV-treated larvae, 82.5 % (52.6–95.7) in 500 nM MDPV-treated larvae, and 83.3 % (66.7–100.0) in 5 µM MDPV-treated larvae. In the 500 ms interval, the corresponding values were 66.7 % (46.4–83.9), 58.3 % (36.0–71.7), 73.8 % (48.3–82.8), and 82.5 % (64.3–100.0), respectively (individual data are available at Supplementary Dataset 5). Statistical analysis confirmed that the differences among control and MDPV-treated groups were non-significant.

2.4. Gene Expression Analysis

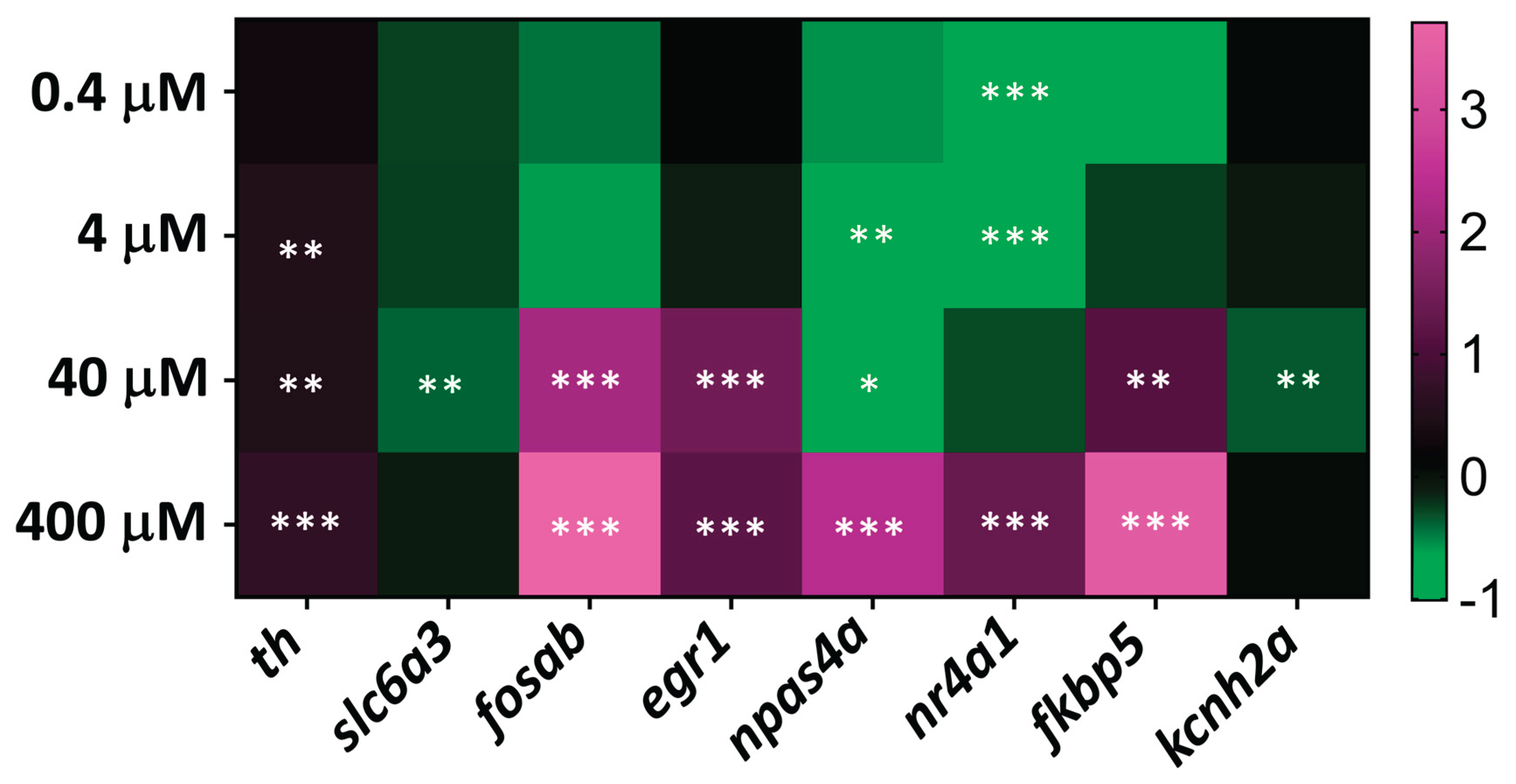

To explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the behavioral effects of MDPV, we assessed the transcriptional response of a set of early-response genes potentially modulated by psychostimulants such as dextroamphetamine or synthetic cathinones. A 2 h exposure period was selected to capture rapid gene expression changes induced by acute MDPV exposure. The analyzed genes included th (tyrosine hydroxylase), slc6a3 (DAT), kcnh2a (potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 2a), kcnh6a (potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 6a, hERG-like IKr), kcnq1 (potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1, IKs), fosab (v-fos murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog Ab), egr1 (early growth response 1), npas4a (neuronal PAS domain protein 4a), nr4a1 (nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1), and fkbp5 (fkb propyl isomerase 5).

Three-day-old zebrafish embryos were exposed to MDPV concentrations ranging from 0.4 to 400 µM for 2 h. As shown in

Figure 5, the expression profile revealed distinct transcriptional modulation depending on the concentration. Exposure to 4-400 µM MDPV led to a mild but significant upregulation of

th, suggesting enhanced dopaminergic activity. In contrast,

slc6a3 and

kcnh2a were significantly downregulated only at 40 µM.

Among immediate-early genes, fosab, npas4a, and fkbp5 were markedly upregulated in the 40–400 µM range, consistent with neuronal activation and stress-related signaling. nr4a1 displayed a biphasic response, being downregulated at low concentrations (0.4–4 µM) and upregulated at 400 µM. Similarly, npas4a showed downregulation at 4-40 µM and strong upregulation at 400 µM.

No significant transcriptional modulation was detected for kcnh6a (IKr) and kcnq1 (IKs) at any of the MDPV concentrations tested.

3. Discussion

This study provides an integrated evaluation of the cardiotoxic and neurobehavioral effects of the synthetic cathinone 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in zebrafish embryos and larvae. By combining physiological, behavioral, and molecular analyses across developmental stages, we demonstrated that MDPV exerts a potent negative chronotropic effect and concentration-dependent transcriptional modulation of early-response genes, while producing no significant alterations in sensorimotor gating. These findings highlight the value of the zebrafish model for characterizing both the direct and system-level consequences of emerging psychostimulants.

3.1. Cardiotoxicity of MDPV in Zebrafish Embryos

3.1.1. Chronotropic and Conduction Effects of MDPV in Zebrafish Embryos

Psychostimulant drugs, including methamphetamine, cocaine, and synthetic cathinones, are known to induce tachycardia, conduction and repolarization disturbances, and QT interval prolongation [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Compounds that cause repolarization abnormalities in humans or mammalian models typically produce bradycardia and atrioventricular (AV) block in zebrafish embryos [

17,

28,

29]. Consistent with this, the present study found that acute exposure to MDPV produced a marked, concentration-dependent depression of cardiac activity in 3 dpf embryos. Both atrial and ventricular beating frequencies decreased significantly, but ventricular suppression was more pronounced, resulting in AV conduction blocks at higher concentrations. These findings align with the severe arrhythmias and cardiac arrest reported in mammalian models [

7,

12], clinical intoxications [

5,

8], and previous zebrafish studies with MDPV [

17].

The preferential vulnerability of ventricular tissue suggests interference with repolarizing potassium currents mediated by the zebrafish orthologs of KCNH2 (hERG) [

28,

29,

30,

31] or KCNQ1 channels [

27], which represent known molecular targets of synthetic cathinones. The absence of hyperthermic confounding in zebrafish reinforces the interpretation that MDPV can directly impair cardiac excitability through ion-channel modulation rather than systemic thermal effects. Interestingly, a recent study using human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes—another model that avoids hyperthermia as a confounding variable—reported that MDPV caused a concentration-dependent reduction in spike amplitude and beat rate, together with prolongation of the field potential duration (FPD), a parameter analogous to the QT interval [

32]. These findings are fully consistent with those obtained in the present zebrafish model.

The 24-h LC₅₀ value determined in the present study (344 µM) was higher than that previously reported by Teixidó

et al. [

17] (135 µM). This discrepancy may reflect differences in the developmental stages of the embryos used for LC₅₀ determination, namely 3 dpf in the current study versus 4 dpf in Teixidó

et al. Importantly, the observed lethality at high MDPV concentrations cannot be directly ascribed to cardiac failure. Zebrafish heart mutants usually survive until 7 dpf with limited or no functional circulation, because during the embryonic period, oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange occur largely through the skin [

33]. Consequently, mortality likely reflects systemic cellular toxicity rather than hemodynamic collapse per se. Future work should include the evaluation of cell death and oxidative stress markers in the exposed embryos.

3.1.2. Effects of MDPV on Cardiac Mechanical Performance

In addition to the pronounced bradycardia and atrioventricular conduction blocks, quantitative analysis of ventricular mechanics revealed a clear concentration-dependent reduction in cardiac output (CO), with significant decreases at all MDPV concentrations tested. Ejection fraction (EF) was also reduced at the highest concentration (480 µM), whereas fractional shortening (FS) and stroke volume (SV) remained statistically unchanged relative to controls. These results indicate that MDPV primarily impairs cardiac performance through chronotropic and conduction mechanisms, while ventricular contractility is affected only at higher exposure levels.

The selective reduction of CO across all concentrations is consistent with the severe bradycardia observed, since CO integrates both stroke volume and heart rate. Even moderate slowing of cardiac rhythm or partial atrioventricular block can substantially diminish effective blood flow without requiring a parallel reduction in contractile strength. The further decline in EF at 480 µM suggests that, beyond a certain threshold, MDPV also compromises ventricular contractility, possibly through interference with ion-channel activity, particularly KCNQ1-mediated repolarizing currents, which are highly sensitive to synthetic cathinones and structurally related stimulants [

27]. It is important to consider that a significant decrease in EF is considered an indicator of heart failure [

34]. Such dual chronotropic and inotropic impairment aligns with reports of arrhythmias and pump failure in mammalian models and human MDPV intoxications [

7,

24,

25,

26,

27].

The apparent discrepancy between the bradycardia observed in zebrafish embryos and the tachycardia typically reported in mammals following exposure to psychostimulants such as MDPV [

4,

7,

24,

25,

26,

27] likely reflects developmental differences in cardiac autonomic regulation. Zebrafish studies have shown that the sympatho-vagal balance develops gradually between 2 and 15 days post-fertilization, with autonomic reflexes still incomplete at 5 dpf [

35]. At 3 dpf, sympathetic innervation of the heart is just beginning to form, and the cardiac rhythm remains predominantly myogenic, with limited catecholaminergic modulation [

36]. As a result, MDPV cannot trigger the systemic sympathetic activation that underlies tachycardia in mammals. Instead, its effects in zebrafish are dominated by direct electrophysiological interference with cardiac ion channels—particularly hERG- and KCNQ1-like repolarizing currents—leading to conduction delay and bradyarrhythmia. Therefore, the zebrafish phenotype most likely reflects direct cardiotoxicity in the absence of mature autonomic compensation, rather than a true pharmacological opposition to mammalian outcomes.

Together, these results confirm that MDPV has intrinsic cardiotoxic potential at micromolar concentrations, manifesting as conduction failure rather than simple bradycardia.

3.2. Behavioral Effects: Locomotion and Sensorimotor Gating

Increases in locomotor activity following administration of MDPV and other synthetic cathinones have been reported in multiple experimental paradigms [

37,

38]. In the present study, however, MDPV induced a significant decrease in basal locomotor activity in 5 dpf larvae, an effect consistent with an overall suppressive rather than stimulatory action of this compound. A similar reduction in locomotor activity was recently reported in 5–6 dpf zebrafish larvae exposed for 3 h to 10–100 mM of the synthetic cathinone pyrovalerone, a compound belonging to the same structural family as MDPV [

21]. In contrast, exposure of 5 dpf larvae to mephedrone for 3 h resulted in a mild but significant increase in locomotor activity [

39]. Variations in exposure duration, cathinone subtype, or zebrafish strain may account for these divergent outcomes. The divergent locomotor effects of MDPV observed between zebrafish and mammalian models likely reflect species- and developmental stage–specific differences in neurophysiology and pharmacokinetics.

Some psychoactive compounds, including dextroamphetamine, affect sensorimotor gating in a species-dependent manner, producing enhanced PPI in humans [

40] but decreased PPI in rodents [

41], consistent with divergent dopaminergic sensitivities between species. The effects of MDPV and related pyrrolidine-containing cathinones derivatives on sensorimotor gating remain poorly characterized and inconsistent [

38,

42]. Although the dopaminergic agonist apomorphine has been shown to impair PPI in zebrafish larvae via D₂ receptor activation [

43], no previous studies have examined whether psychostimulant compounds can modulate PPI in this model organism. Our results demonstrate for the first time that exposure to dextroamphetamine, a DA releaser agent inducing phasic increases of extracellular DA [

44] enhances PPI in 7 dpf larvae, and that this effect is fully reversed by co-exposure with the D₂ antagonist haloperidol. Thus, the zebrafish response to dextroamphetamine parallels that reported in humans [

40]. In contrast, MDPV did not significantly alter PPI across the tested concentration range. Notably, Horsley and colleagues (2018) [

45] demonstrated that only at the higher dose tested (4 mg/kg), MDPV decreased PPI in rats, but transiently, when plasma and brain levels were at their peak. Altogether, these findings suggest that MDPV primarily acts through a cocaine-like mechanism as a DAT blocker, producing tonic and sustained elevations in extracellular DA [

46,

47]. Given its limited direct D₂ receptor activity [

3], MDPV may therefore elicit weaker or more complex receptor-mediated signaling [

48] under acute exposure conditions.

3.3. Early Gene Expression Responses

Gene expression profiling revealed that short-term MDPV exposure (0.4–400 µM, 2 h) elicited distinct transcriptional signatures depending on concentration. The mild but significant up-regulation of

th (tyrosine hydroxylase) observed between 4 and 400 µM suggests enhanced dopaminergic synthetic activity, likely reflecting a compensatory response to DA reuptake blockade induced by MDPV. Similar transient increases in TH mRNA have been described following acute methamphetamine (METH) administration in discrete dopaminergic nuclei of the rodent brain [

49,

50].

th up-regulation was detected in the brain of adult zebrafish after 3 h of METH exposure [

19], and in

Carassius auratus following treatment with d-amphetamine [

51], supporting the view that increased dopaminergic turnover is an early adaptive response to psychostimulant challenge in vertebrates.

Conversely, a transient down-regulation of

slc6a3 (dopamine transporter, DAT) was detected in embryos exposed for 3 h to 40 µM MDPV. This finding is consistent with the negative feedback mechanisms reported in mammalian systems, where sustained elevations of extracellular dopamine or prolonged transporter blockade led to decreased

slc6a3 transcription. Reduced DAT expression has been documented in the brains of postnatal rats after repeated amphetamine administration [

52], and in rats chronically exposed to cocaine [

53], suggesting that compensatory down-regulation of the transporter constitutes a conserved homeostatic mechanism limiting dopaminergic overstimulation. The concordance between zebrafish and rodent data indicates that even brief MDPV exposure is sufficient to engage transcriptional feedback loops regulating DA synthesis and reuptake.

Acute MDPV exposure triggered rapid and concentration-dependent transcriptional changes typical of psychostimulant action. The marked up-regulation of the immediate-early genes

fosab and

egr1 at ≥40 µM parallels the activity-dependent genomic response described for dopaminergic and glutamatergic drugs [

54,

55]. Both genes, induced through Ca²⁺/MAPK signaling, are classical markers of neuronal activation and synaptic remodeling [

56].

npas4a and

nr4a1 showed biphasic regulation, with the expression down-regulated at low doses and up-regulated at 400 µM, indicating distinct activation thresholds. NPAS4 maintains excitatory–inhibitory balance and limits excitotoxic and inflammatory stress [

57,

58], whereas NR4A1 integrates dopamine receptor activation with mitochondrial and inflammatory signaling, balancing adaptation and apoptosis [

54,

58]. Their coordinated induction at high concentrations likely represents recruitment of homeostatic and protective transcriptional pathways in response to intense neuronal activation.

The co-chaperone

fkbp5, a well-known glucocorticoid-responsive gene, was also significantly up-regulated at 40–400 µM MDPV. FKBP5 is tightly connected with NR4A nuclear receptors and participates in the regulation of inflammatory and neurodegenerative processes [

58,

59]. The parallel induction of

fkbp5 and

nr4a1 observed here likely reflects coordinated activation of GR- and NR4A-dependent transcriptional networks, linking dopaminergic overactivity with endocrine and immune stress signaling.

Although

kcnh2a was transiently down-regulated at 40 µM, MDPV did not change the expression of

kcnh6a or

kcnq1 at any concentration tested. This finding is mechanistically relevant, as

kcnh6a, rather than

kcnh2a, encodes the functionally dominant ventricular hERG-like channel mediating IKr in zebrafish [

60]. Acute IKr blockade has been reported to produce AV-block phenotypes comparable to those observed here [

61], and KCNQ1-dependent IKs contributes to ventricular repolarization and arrhythmia susceptibility [

61,

62]. Thus, the modest

kcnh2a down-regulation does not appear to drive the observed cardiotoxic effects, which are more consistent with direct functional interference with repolarizing K

+ channels than with early genomic remodeling of their expression.

Overall, the combined upregulation of

fosab,

egr1,

npas4a,

nr4a1, and

fkbp5 defines a conserved transcriptional program integrating neuronal activation, stress adaptation, and inflammatory control. These early molecular events parallel those reported for other psychostimulants in zebrafish and mammals [

54,

55], underscoring the suitability of the model for elucidating the mechanistic basis of MDPV neurotoxicity.

3.4. Integrative Interpretation and Relevance

The combined physiological, behavioral, and molecular data depict a coherent framework of MDPV action in zebrafish embryos. At higher concentrations, MDPV directly compromises cardiac excitability, leading to conduction failure and mortality. However, causality between cardiotoxic endpoints and mortality cannot be inferred at 3 dpf zebrafish embryos, when cutaneous gas exchange allows survival without functional circulation [

33]. At sublethal levels, it suppresses locomotion and triggers dopaminergic and stress-related transcriptional responses without disrupting sensorimotor gating. This divergence suggests that the molecular activation of dopaminergic pathways precedes overt neurobehavioral deficits, possibly reflecting the predominance of transporter blockade over receptor-mediated signaling during acute exposure.

The preservation of kcnh6a and kcnq1 expression despite severe bradyarrhythmia reinforces the conclusion that MDPV acts as a direct cardiotoxicant targeting repolarization, while neurobehavioral effects emerge at much lower concentrations.

From a toxicodynamic perspective, comparison of concentration–response relationships across endpoints provides insight into MDPV’s functional safety margin. The EC₅₀ for suppression of basal locomotor activity (2.51 µM), a proxy for central behavioral or psychostimulant-related effects, was approximately 91-fold lower than the EC₅₀ for atrioventricular conduction block (228 µM). This difference indicates that functional cardiac toxicity occurs at concentrations far exceeding those producing neurobehavioral alterations, suggesting that acute exposures sufficient to elicit psychotropic effects remain well below the cardiotoxic threshold in zebrafish. Nonetheless, the steep concentration–response slopes observed for both endpoints imply a relatively narrow dynamic range between behavioral and cardiac domains, consistent with the abrupt cardiovascular collapse reported in severe MDPV intoxications in mammals.

The integration of cardiac, behavioral, and gene-expression endpoints highlights the zebrafish’s ability to disentangle the mechanistic layers of psychostimulant toxicity and to predict mammalian outcomes without confounding them with hyperthermia or systemic stress. Such a multi-level approach upgrades zebrafish from a screening model to a platform capable of identifying conserved signatures of neuro- and cardiotoxicity.

3.5. Conclusions and Perspectives

This study demonstrates that zebrafish provide a sensitive and integrative model for assessing the cardiotoxic and neurobehavioral effects of synthetic cathinones. MDPV induced concentration-dependent bradycardia and conduction block, reduced locomotor activity, and rapidly modulated dopaminergic and stress-related genes, without affecting sensorimotor gating. These findings reveal that zebrafish can distinguish between mechanistic components of psychostimulant action and toxicity, offering a valuable system for early hazard identification.

The preservation of kcnh6a and kcnq1 expression despite severe conduction disturbances supports a direct, functional interference of MDPV with repolarizing K⁺ currents rather than transcriptional remodeling, reinforcing its intrinsic cardiotoxic potential. Comparison of concentration–response relationships across endpoints further revealed that behavioral alterations occur at concentrations nearly two orders of magnitude lower than those producing cardiac conduction failure. This quantitative distinction defines a functional safety margin between neurobehavioral engagement and cardiotoxic risk and highlights the translational potential of zebrafish assays for evaluating relative thresholds of adverse drug effects.

Future studies should extend this framework to chronic exposures and in vivo imaging approaches to clarify how acute molecular responses evolve into long-term neurocardiac dysfunction.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Zebrafish Maintenance and Embryo Production

Wild-type short-fin adult zebrafish were obtained from a commercial supplier (Exopet, Madrid, Spain) and were maintained under a 12 h: 12 h light/dark cycle and a temperature of 28 ± 1°C at the Research and Development Center (CID-CSIC) in a recirculating water system (Aquaneering Inc., San Diego, United States).

The day before each experiment, three females and two males were transferred to a breeding tank. Fertilized eggs were collected within 30 min after lights-on. Only high-quality embryos at the 50 %-epiboly stage were selected under a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ1500, Champigny-sur-Marne, France). Embryos were transferred to a crystallizing dish containing embryo water [Milli-Q water with 90 mg/L Instant Ocean (Aquarium Systems, Sarrebourg, France) and 0.58 mM CaSO₄·2H₂O, pH 6.5–7.0, 750–900 μS/cm conductivity] and incubated at 28 ± 1°C in a climatic chamber (POL-EKO APARATURA KK350, Wodzisław Śląski, Poland) under a 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle until use.

4.2. Chemicals

MDPV (MW = 311.81 g/mol) was synthesized in the University of Barcelona (UB) as hydrochloride salts in a racemic form as previously published [

63]. Stock solutions (10 mM) were freshly prepared on the day of each experiment in Milli-Q water. Working solutions were obtained by dilution in embryo water, and the pH was then adjusted to 8.7–9.0 with 1 M NaHCO₃ to maintain it within the 8.4–9.5 range corresponding to the compound’s pKₐ, thereby ensuring its predominant ionized form throughout the exposure [

64]. Dextroamphetamine (or

d-amphetamine) sulfate was generously provided by Prof. Dr. Camarasa from the University of Barcelona.

4.3. Lethality Test

At 3 dpf, embryos were exposed for 24 h to 0, 60, 120, 240, 300, 360, 420, 480, 540, and 600 µM MDPV in 24-well plates (one embryo per well; n = 16 per group, four replicates per treatment) with 1.5 mL solution per well. Lethality was evaluated at the end of the exposure period, and mortality was expressed as percentage lethality for each concentration.

Concentration–response data were analyzed using a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model constrained between 0 and 100% lethality:

where Y is the percentage of lethality, X the MDPV concentration (µM), LC₅₀ the concentration producing 50% mortality, and Hill the slope factor.

Model fitting and parameter estimation were performed in Python (SciPy 1.11) using nonlinear least-squares regression. Uncertainty was assessed via nonparametric bootstrap resampling (n = 2000 resamples) to derive 95% confidence intervals (CI₉₅) for both LC₅₀ and Hill slope values.

The fitted model yielded an LC₅₀ of 343.8 µM (95% CI: 318.1–369.4 µM) and a Hill slope of 9.81 (95% CI: 6.75–10.00), indicating a steep transition between sublethal and lethal concentrations.

4.4. Cardiotoxicity Assessment

4.4.1. Heart Beating Analysis

Embryos at 3 dpf were exposed for 2 h to 60–480 µM MDPV in 48-well plates (one embryo per well, 1 mL solution). To minimize movement during imaging, embryos were briefly anesthetized (0.08 mg/mL tricaine methane-sulfonate [MS-222], 10 s) and embedded in 3 % methylcellulose on a depression microscope slide. Cardiac activity was recorded laterally with a high-speed camera (Basler ace U acA1440-220 um) attached to a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ1500) at 100 fps for 20 s using Pylon Viewer software at 28 ± 1 °C.

Atrial and ventricular beat frequencies were quantified using DanioScope v1.0 (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands), which derives heart rate from pixel-intensity fluctuations over time [

30]. Atrial and ventricular activity were analyzed separately to assess chamber-specific effects of MDPV. The atrioventricular (AV) ratio, defined as the ratio between atrial and ventricular beat frequencies, was calculated for each embryo as an indicator of conduction efficiency (1.0 = full AV conduction).

To quantify the degree of conduction impairment, the AV ratio was transformed into percentage AV block according to the expression:

where R is the AV ratio. This transformation yields values from 0% (normal conduction) to 100% (complete AV block).

Concentration–response analysis of AV block was performed using a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model constrained between 0 and 100%. The model was fitted to individual replicate data at concentrations ≥60 µM using nonlinear least-squares regression in Python (SciPy 1.11). The equation used was:

where Y is the percentage of AV block, X the MDPV concentration (µM), EC₅₀ the concentration eliciting 50% AV block, and Hill the slope parameter. Model performance and uncertainty were evaluated by nonparametric bootstrap resampling (n = 2000 resamples), from which 95% confidence intervals were calculated for both EC₅₀ and Hill slope.

The fitted model yielded an EC₅₀ of 228.3 µM (95% CI: 208.1–253.3 µM) and a Hill slope of 1.45 (95% CI: 1.30–1.62), defining the midpoint of the transition from synchronous atrial–ventricular conduction to high-degree AV block.

4.4.2. Cardiac Mechanical Performance

To comprehensively assess cardiac function, several parameters were quantified from the heart activity recordings, including fractional shortening (FS), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), and ejection fraction (EF). Together with heart rate, these parameters provide an integrated evaluation of cardiac performance and efficiency in the exposed embryos.

Recorded videos were imported into Fiji (ImageJ distribution), and cardiac parameters were calculated as described by Benslimane et al. [

18] (

Supplementary Figure S5). Three end-diastolic and three end-systolic frames were selected, and the ventricular long axis, short axis, and area were measured in each frame. The mean of the three measurements was then used for analysis. Since the values obtained were expressed in pixels, they were converted to real units (µm) using a calibration factor, according to the following equations:

Using these real unit values, the following cardiac parameters were calculated:

where D

d is the ventricular diameter in diastole, D

s the ventricular diameter in systole, D

L the long-axis ventricular diameter, and D

S the short-axis ventricular diameter.

4.5. Behavioral Assessment

4.5.1. Basal Locomotor Activity

Basal locomotor activity (BLA) was assessed in 5 dpf zebrafish larvae exposed for 2 h to 5 nM–5 µM MDPV. Untreated embryo water served as the control. Recordings were made on the DanioVision platform (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands) under near-infrared illumination with temperature maintained at 28°C. Video tracking was performed using EthoVision XT software (v13 for recording, v16 for analysis).

Locomotor behavior was quantified during three 15-min observation windows (0–15, 45–60, and 105–120 min). For each larva, BLA was defined as the total distance (cm) traveled within each window. Results are presented as percentage of the control values (0 µM).

Concentration–response relationships for the 105–120 min interval were analyzed using a four-parameter logistic (4PL) regression model, fitted to all individual replicates (excluding the 0 µM control, since log(0) is undefined). The model followed the equation:

where Y represents the locomotor response (% control), X the MDPV concentration (µM), Top and Bottom the asymptotic plateaus, Hill the slope, and EC₅₀ the half-maximal effective concentration.

Nonlinear regression was performed in Python (SciPy 1.11) using bounded least-squares fitting with a maximum of 20,000 iterations. The 95 % confidence interval for EC₅₀ was obtained by nonparametric bootstrap resampling (1,000 stratified resamples per concentration). Derived EC₁₀ and EC₉₀ values were calculated by inverting the fitted function at 10 % and 90 % of the response span, respectively. Model reliability was evaluated by inspection of fitted curves and 95 % bootstrap prediction bands.

Nonparametric group comparisons were conducted using Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by pairwise post-hoc analyses, identifying significant locomotor suppression at 0.5 µM and 5 µM (p < 0.05).

4.5.2. Prepulse Inhibition

Prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle response was assessed in 7 dpf larvae, either unexposed (control) or exposed for 30 min to MDPV concentrations ranging from 5 nM to 5 µM, using the Zebra_K+ platform (add-on module for embryos and larvae for Zebra_K [

65]). The 7 dpf developmental stage was selected because, at this age, zebrafish possess a fully functional dopaminergic modulatory circuit, allowing reliable measurement of sensorimotor gating [

23].

The PPI paradigm consisted of three sequential steps. In the prepulse step, five weak auditory stimuli (1000 Hz, 20 µs, 74.8 dB re 20 µPa) that typically elicited 0–10% startle responses were delivered at 120-s interstimulus intervals (ISI). After a 60-s pause, the pulse step comprised five startle-inducing stimuli (1000 Hz, 4 ms, 93.7 dB re 20 µPa) presented at the same 120-s ISI. Following another 60-s rest period, prepulse–pulse pairs were delivered in the PPI step, with 50-ms and 500-ms prepulse–pulse intervals, and a 120-s ISI between successive pairs.

Dextroamphetamine (5 µM) was included as a positive control, as it represents a prototypical amphetamine-type stimulant with well-documented disruptive effects on PPI mediated by enhanced dopaminergic transmission.

4.6. RNA Preparation and qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from pools of six 3 dpf embryos (control or exposed to 0.4–400 µM MDPV) using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) [

66]. RNA concentration and purity were determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop ND-8000, NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). After DNase I treatment (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), RNA was reverse-transcribed with the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

qRT-PCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 System (Roche) using SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) under the following conditions: 95 °C for 15 min, then 45 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Each condition included eight biological and three technical replicates. Primers for

th,

slc6a3,

fosab,

egr1,

npas4a,

nr4a1,

fkbp5,

kcnh2a, kcnh6a, and

kcnq1 were designed with Primer Express 2.0 (Applied Biosystems) and validated with Primer-BLAST (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast). Primer sequences and the reference gene

ppiaa (peptidyl-prolyl isomerase A) are listed in

Supplementary Table S2. Relative mRNA levels were normalized to

ppiaa and fold-changes calculated by the ΔΔCt method [

67].

4.7. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v29 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA), and visualizations with GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data normality was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Results are presented as mean ± SEM (parametric data) or median [IQR] (non-parametric data).

Nonparametric bootstrap resampling (stratified by concentration, 2000 iterations) was used to derive 95% percentile confidence intervals for nonlinear curve parameters (EC₅₀/LC₅₀ and Hill slope), providing robust estimation of uncertainty without relying on distributional assumptions for residuals or replicate values. Nonlinear regression was performed using a four-parameter logistic model fit by bounded least-squares minimization.

Cardiotoxicity data were analyzed by mixed repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test to evaluate concentration and chamber effects (atrium vs. ventricle). When appropriate, separate one-way ANOVAs were run for each chamber.

Locomotor activity data (total distance traveled) were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test since normality assumptions were not met. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Table S1. Statistical analysis of gene expression after 2 h MDPV exposure in 3 dpf zebrafish embryos. ΔΔCt values were normalized within each experiment; Supplementary Table S2. List of primers used for the qPCR; Supplementary Figure S1. MDPV lethality in 3 dpf zebrafish embryos after 24 h exposure; Supplementary Figure S2. AV block induced by MDPV in 3 dpf zebrafish embryos after 2 h exposure; Supplementary Figure S3. Concentration-dependent effects of MDPV on basal locomotor activity (BLA) in 5 dpf zebrafish larvae; Supplementary Supplementary Figure S4. Effects on prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle response (ASR) in zebrafish 7 days post-fertilization zebrafish larvae exposed to d-amphetamine; Supplementary Figure S5 ImageJ user interface showing steps used for cardiac parameter measurement in 3 dpf zebrafish embryo; Supplementary Dataset 1. Results of lethality in 3 days post-fertilization zebrafish embryos exposed for 24 h to different concentrations of MDPV (60-600 mM); Supplementary Dataset 2. Beat frequency (beat per minute) in the atrium and ventricle of 3 days post-fertilizacion zebrafish embryos control and exposed for 2 h to different MDPV concentrations (60-480 mM); Supplementary Dataset 3. Effects of 2 h exposure MDPV (120-480 mM) on ventricular performance in 3 dpf zebrafish embryos; Supplementary Dataset 4. Basal locomotor activity (BLA) values at different exposure times (0-15 min, 45-60 min, and 105-120 min) and MDPV concentrations in 5 days post-fertilization zebrafish embryos; Supplementary Dataset 5. Sensorimotor gating in 7-days-post-fertilization zebrafish larvae, either untreated (control) or exposed for 30 min to different MDPV concentrations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.R., R.L.A.; Methodology: O.A., N.T.; Formal Analysis: D.R.; Investigation: O.A., N.T., J.B., E.P.; Resources: D.R., R.L.A.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: D.R., O.A., N.T., J.B., E.P., R.L.A.; Writing – Review & Editing: D.R., O.A., N.T., J.B., E.P., R.L.A.; Visualization: D.R., O.A., J.B.; Supervision: D.R., R.L.A.; Project Administration: D.R.; Funding Acquisition: D.R., R.L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (grant numbers PID2023-148502OB-C21 and PID2022-137541OB-I00), and Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas (2024I057). RLA belongs to 2021SGR0090 from Generalitat de Catalunya. O.A. and N.T. were supported by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, co-financed by the Spanish Government and the European Social Fund (grant numbers PREP2022-104748 and PREP2023-001814, respectively).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the CID-CSIC and conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines under a license from the local government (agreement number 11336, date 18 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript and its Supplementary Material file or will be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT v5 for the purpose of proofreading of English writing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pieprzyca, E.; Skowronek, R.; Nižnanský, Ľ.; Czekaj, P. Synthetic cathinones – From natural plant stimulant to new drug of abuse. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.H.; Partilla, J.S.; Lehner, K.R.; Thorndike, E.B.; Hoffman, A.F.; Holy, M.; Rothman, R.B.; Goldberg, S.R.; Lupica, C.R.; Sitte, H.H.; et al. Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive “bath salts” products. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmler, L.D.; Buser, T.A.; Donzelli, M.; Schramm, Y.; Dieu, L.H.; Huwyler, J.; Chaboz, S.; Hoener, M.C.; Liechti, M.E. Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 168, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, M.; Mondola, R. Synthetic cathinones: Chemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of a new class of designer drugs of abuse marketed as “ bath salts” or “ plant food. ” Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 211, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.M. Mephedrone and 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV): Synthetic Cathinones With Serious Health Implications. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyatkin, E.A.; Kim, A.H.; Wakabayashi, K.T.; Baumann, M.H.; Shaham, Y. Effects of Social Interaction and Warm Ambient Temperature on Brain Hyperthermia Induced by the Designer Drugs Methylone and MDPV. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClenahan, S.J.; Hambuchen, M.D.; Simecka, C.M.; Gunnell, M.G.; Berquist, M.D.; Owens, S.M. Cardiovascular effects of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 195, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, T.H.; Cline-Parhamovich, K.; Lajoie, D.; Parsons, L.; Dunn, M.; Ferslew, K.E. Deaths involving methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in upper east tennessee. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, 1558–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesha, K.; Boggs, C.L.; Ripple, M.G.; Allan, C.H.; Levine, B.; Jufer-Phipps, R.; Doyon, S.; Chi, P.; Fowler, D.R. Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (“Bath Salts”),Related Death: Case Report and Review of the Literature, J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, 1654–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, D.; Manfredi, A.; Zanon, M.; Fattorini, P.; Scopetti, M.; Neri, M.; Frisoni, P.; D’Errico, S. Synthetic Cannabinoids and Cathinones Cardiotoxicity: Facts and Perspectives. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 19, 2038–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, R.; Sun, M.; Li, Y.; Yin, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Wu, B.; Yang, G.; et al. The pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies of heat stroke-induced myocardial injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1286556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles Schindler, C.W.; Schindler, C.W.; Thorndike, E.B.; Suzuki, M.; Rice, K.C.; Baumann, M.H. Pharmacological mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular effects of the “bath salt” constituent 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, C.A.; Peterson, R.T. Zebrafish as tools for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Champagne, D.L.; Spaink, H.P.; Richardson, M.K. Zebrafish embryos and larvae: A new generation of disease models and drug screens. Birth Defects Res. Part C - Embryo Today Rev. 2011, 93, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainier, D.Y.R.; Fishman, M.C. The zebrafish as a model system to study cardiovascular development. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1994, 4, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkers, J. Zebrafish as a model to study cardiac development and human cardiac disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 91, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixidó, E.; Riera-Colomer, C.; Raldúa, D.; Pubill, D.; Escubedo, E.; Barenys, M.; López-Arnau, R. First-Generation Synthetic Cathinones Produce Arrhythmia in Zebrafish Eleutheroembryos: A New Approach Methodology for New Psychoactive Substances Cardiotoxicity Evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benslimane, F.M.; Zakaria, Z.Z.; Shurbaji, S.; Abdelrasool, M.K.A.; Al-Badr, M.A.H.I.; Al Absi, E.S.K.; Yalcin, H.C. Cardiac function and blood flow hemodynamics assessment of zebrafish (Danio rerio) using high-speed video microscopy. Micron 2020, 136, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedrossiantz, J.; Bellot, M.; Dominguez-García, P.; Faria, M.; Prats, E.; Gómez-Canela, C.; López-Arnau, R.; Escubedo, E.; Raldúa, D. A Zebrafish Model of Neurotoxicity by Binge-Like Methamphetamine Exposure. 2021, 12, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikova, T.O.; Khatsko, S.L.; Eltsov, O.S.; Shevyrin, V.A.; Kalueff, A. V. When fish take a bath: Psychopharmacological characterization of the effects of a synthetic cathinone bath salt ‘flakka’ on adult zebrafish. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2019, 73, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souders, C.L.; Davis, R.H.; Qing, H.; Liang, X.; Febo, M.; Martyniuk, C.J. The psychoactive cathinone derivative pyrovalerone alters locomotor activity and decreases dopamine receptor expression in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Atienza, P.; Sancho, E.; Ferrando, M.D.; Armenta, S. Danio rerio embryo as in vivo model for the evaluation of the toxicity and metabolism of pyrovalerone cathinones. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 286, 117174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagkalidou, N.; Aljabasini, O.; Pujol, S.; Prats, E.; Porta, J.M.; Barata, C.; Raldúa, D. Zebra_K + : High-Throughput Analysis of Acoustic Startle Response Plasticity in Zebrafish Embryos and Larvae in Neurotoxicity Testing.

- Havakuk, O.; Rezkalla, S.H.; Kloner, R.A. The Cardiovascular Effects of Cocaine. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, J.F.; Lavins, E.S.; Engelhart, D.; Armstrong, E.J.; Snell, K.D.; Boggs, P.D.; Taylor, S.M.; Norris, R.N.; Miller, F.P. Postmortem Tissue Distribution of MDPV Following Lethal Intoxication by “Bath Salts”*. [CrossRef]

- Al-Abri, S.A.; Woodburn, C.; Olson, K.R.; Kearney, T.E. Ventricular Dysrhythmias Associated with Poisoning and Drug Overdose: A 10-Year Review of Statewide Poison Control Center Data from California. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2015, 15, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, S.; Saitoh, H.; Kasahara, S.; Chiba, F.; Torimitsu, S.; Abe, H.; Yajima, D.; Iwase, H. Relationship between KCNQ1 (LQT1) and KCNH2 (LQT2) gene mutations and sudden death during illegal drug use. Sci. Reports 2018 81 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milan, D.J.; Peterson, T.A.; Ruskin, J.N.; Peterson, R.T.; MacRae, C.A. Drugs that induce repolarization abnormalities cause bradycardia in zebrafish. Circulation 2003, 107, 1355–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langheinrich, U.; Vacun, G.; Wagner, T. Zebrafish embryos express an orthologue of HERG and are sensitive toward a range of QT-prolonging drugs inducing severe arrhythmia. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003, 193, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvrit, S.; Bossaer, J.; Lee, J.; Collins, M.M. Modeling Human Cardiac Arrhythmias: Insights from Zebrafish. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genge, C.E.; Lin, E.; Lee, L.; Sheng, X.Y.; Rayani, K.; Gunawan, M.; Stevens, C.M.; Li, A.Y.; Talab, S.S.; Claydon, T.W.; et al. The zebrafish heart as a model of mammalian cardiac function. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 171, 99–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwartsen, A.; de Korte, T.; Nacken, P.; de Lange, D.W.; Westerink, R.H.S.; Hondebrink, L. Cardiotoxicity screening of illicit drugs and new psychoactive substances (NPS) in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes using microelectrode array (MEA) recordings. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2019, 136, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainier, D.Y.R.; Fouquet, B.; Chen, J.N.; Warren, K.S.; Weinstein, B.M.; Meiler, S.E.; Mohideen, M.A.P.K.; Neuhauss, S.C.F.; Solnica-Krezel, L.; Schier, A.F.; et al. Mutations affecting the formation and function of the cardiovascular system in the zebrafish embryo. Development 1996, 123, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.P.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Januzzi, J.L. Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerte, T.; Prem, C.; Mairösl, A.; Pelster, B. Development of the sympatho-vagal balance in the cardiovascular system in zebrafish (Danio rerio) characterized by power spectrum and classical signal analysis. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, K.D.; Hoyt, C.; Feldman, S.; Blunt, L.C.; Raymond, A.; Page-McCaw, P.S. Cardiac response to startle stimuli in larval zebrafish: Sympathetic and parasympathetic components. Am. J. Physiol. - Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 298, 1288–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotti, G.; Canazza, I.; Caffino, L.; Bilel, S.; Ossato, A.; Fumagalli, F.; Marti, M. The Cathinones MDPV and α-PVP Elicit Different Behavioral and Molecular Effects Following Acute Exposure. Neurotox. Res. 2017, 32, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, R.A.; Rawls, S.M. Behavioral pharmacology of designer cathinones: A review of the preclinical literature. Life Sci. 2014, 97, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O.; Ribeiro, C.; Félix, L.; Gaivão, I.; Carrola, J.S. Effects of acute metaphedrone exposure on the development, behaviour, and DNA integrity of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 49567–49576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitty, K.; Albrecht, M.A.; Graham, K.; Kerr, C.; Lee, J.W.Y.; Iyyalol, R.; Martin-Iverson, M.T. Dexamphetamine effects on prepulse inhibition (PPI) and startle in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014, 231, 2327–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, C.; Jackson, D.M.; Zhang, J.; Svensson, L. Prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle, a measure of sensorimotor gating: Effects of antipsychotics and other agents in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1995, 52, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinterova-Leca, N.; Horsley, R.R.; Danda, H.; Žídková, M.; Lhotková, E.; Šíchová, K.; Štefková, K.; Balíková, M.; Kuchař, M.; Páleníček, T. Naphyrone (naphthylpyrovalerone): Pharmacokinetics, behavioural effects and thermoregulation in Wistar rats. Addict. Biol. 2021, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, H.A.; Granato, M. Sensorimotor gating in larval zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 4984–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daberkow, D.P.; Brown, H.D.; Bunner, K.D.; Kraniotis, S.A.; Doellman, M.A.; Ragozzino, M.E.; Garris, P.A.; Roitman, M.F. Amphetamine paradoxically augments exocytotic dopamine release and phasic dopamine signals. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsley, R.R.; Lhotkova, E.; Hajkova, K.; Feriancikova, B.; Himl, M.; Kuchar, M.; Páleníček, T. Behavioural, Pharmacokinetic, Metabolic, and Hyperthermic Profile of 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in the Wistar Rat. Front. psychiatry 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heien, M.L.A.V.; Khan, A.S.; Ariansen, J.L.; Cheer, J.F.; Phillips, P.E.M.; Wassum, K.M.; Wightman, R.M. Real-time measurement of dopamine fluctuations after cocaine in the brain of behaving rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 10023–10028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, J.; Goyal, A.; Rusheen, A.E.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Berk, M.; Kim, J.H.; Tye, S.J.; Blaha, C.D.; Bennet, K.E.; Jang, D.P.; et al. Cocaine-Induced Changes in Tonic Dopamine Concentrations Measured Using Multiple-Cyclic Square Wave Voltammetry in vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyer, J.K.; Herrik, K.F.; Berg, R.W.; Hounsgaard, J.D. Influence of phasic and tonic dopamine release on receptor activation. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 14273–14283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrucci, M.; Busceti, C.L.; Nori, S.L.; Lazzeri, G.; Bovolin, P.; Falleni, A.; Mastroiacovo, F.; Pompili, E.; Fumagalli, L.; Paparelli, A.; et al. Methamphetamine induces ectopic expression of tyrosine hydroxylase and increases noradrenaline levels within the cerebellar cortex. Neuroscience 2007, 149, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A.A.; Herring, N.R.; Schaefer, T.L.; Hemmerle, A.M.; Dickerson, J.W.; Seroogy, K.B.; Vorhees, C. V.; Williams, M.T. Neurotoxic (+)-methamphetamine treatment in rats increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tropomyosin receptor kinase B expression in multiple brain regions. Neuroscience 2011, 184, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ne Volkoff, H.; Volkoff, H.; Ne Volkoff, H. The effects of amphetamine injections on feeding behavior and the brain expression of orexin, CART, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 39, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeboonngam, T.; Pramong, R.; Sae-ung, K.; Govitrapong, P.; Phansuwan-Pujito, P. Neuroprotective effects of melatonin on amphetamine-induced dopaminergic fiber degeneration in the hippocampus of postnatal rats. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 64, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letchworth, S.R.; Sexton, T.; Childers, S.R.; Vrana, K.E.; Vaughan, R.A.; Davies, H.M.L.; Porrino, L.J. Regulation of rat dopamine transporter mRNA and protein by chronic cocaine administration. J. Neurochem. 1999, 73, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zygmunt, M.; Piechota, M.; Rodriguez Parkitna, J.; Korostyński, M. Decoding the transcriptional programs activated by psychotropic drugs in the brain. Genes, Brain Behav. 2019, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M.T.; Jayanthi, S.; Wulu, J.A.; Beauvais, G.; Ladenheim, B.; Martin, T.A.; Krasnova, I.N.; Hodges, A.B.; Cadet, J.L. Chronic methamphetamine exposure suppresses the striatal expression of members of multiple families of immediate early genes (IEGs) in the rat: Normalization by an acute methamphetamine injection. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011, 215, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirnaru, M.D.; Melis, C.; Fanutza, T.; Naphade, S.; Tshilenge, K.T.; Muntean, B.S.; Martemyanov, K.A.; Plotkin, J.L.; Ellerby, L.M.; Ehrlich, M.E. Nuclear receptor Nr4a1 regulates striatal striosome development and dopamine D1 receptor signaling. eNeuro 2019, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechota, M.; Korostynski, M.; Solecki, W.; Gieryk, A.; Slezak, M.; Bilecki, W.; Ziolkowska, B.; Kostrzewa, E.; Cymerman, I.; Swiech, L.; et al. The dissection of transcriptional modules regulated by various drugs of abuse in the mouse striatum. Genome Biol. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Ma, D.; Zhuo, L.; Pang, X.; You, J.; Feng, J. Progress and Promise of Nur77-based Therapeutics for Central Nervous System Disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 19, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, F.C.; Klarić, T.S.; Koblar, S.A.; Lewis, M.D. The role of the neuroprotective factor Npas4 in cerebral ischemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 29011–29028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genge, C.E.; Muralidharan, P.; Kemp, J.; Hull, C.M.; Yip, M.; Simpson, K.; Hunter, D. V.; Claydon, T.W. Zebrafish cardiac repolarization does not functionally depend on the expression of the hERG1b-like transcript. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2024, 476, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vornanen, M.; Badr, A.; Haverinen, J. Cardiac arrhythmias in fish induced by natural and anthropogenic changes in environmental conditions. J. Exp. Biol. 2024, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverinen, J.; Hassinen, M.; Vornanen, M. Effect of Channel Assembly (KCNQ1 or KCNQ1 + KCNE1) on the Response of Zebrafish IKsCurrent to IKsInhibitors and Activators. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 79, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novellas, J.; López-Arnau, R.; Carbó, M.L.; Pubill, D.; Camarasa, J.; Escubedo, E. Concentrations of MDPV in rat striatum correlate with the psychostimulant effect. J. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 29, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Hartmann-Fischbach, P.; Krueger, T.R.; Wells, T.L.; Feineman, A.R.; Compton, J.C. Rapid and Sensitive Analysis of 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone in Equine Plasma Using Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2012, 36, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.; Tagkalidou, N.; Multisanti, C.R.; Pujol, S.; Aljabasini, O.; Prats, E.; Faggio, C.; Porta, J.M.; Barata, C.; Raldúa, D. Zebra_K, a kinematic analysis automated platform for assessing sensitivity, habituation and prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response in adult zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, M.; Bedrossiantz, J.; Ramírez, J.R.R.; Mayol, M.; García, G.H.; Bellot, M.; Prats, E.; Garcia-Reyero, N.; Gómez-Canela, C.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; et al. Glyphosate targets fish monoaminergic systems leading to oxidative stress and anxiety. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2 C T Method. METHODS 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).