1. Introduction

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease that affects 1.5% of the global population over the age of 65 years [

1]. Despite years of focused research, current treatments are not fully effective and are generally associated with substantial side effects. Some of the motor disorders manifested in patients diagnosed with PD are bradykinesia, hypokinesia, impaired balance, rigidity, resting tremors and smooth muscle spasms [

2,

3]. Axial rigidity and postural instability may contribute to turning difficulty, one motor hallmark symptom commonly found in PD patients [

4]. All these symptoms are due to dopaminergic neuron loss in substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), consequently leading to the disruption of dopamine input to the striatum and finally motor impairment [

5,

6]. While the initial symptoms of PD are motor, the progression of the disease is frequently associated with psychiatric symptoms, with PD psychosis (PDP) occurring in 40-80% of the patients [

7]. The etiology of PD is complex and along with genetic factors, various environmental contributors have been linked with the increased risk of the disease manifestation. Extensive research over the years has revealed that several genes, like SNCA, PINK1, LRRK2 and PARK2 are involved in PD pathogenesis, with number of other genes being under consideration and further studies [

8,

9,

10]. Some of the non-genetic risk factors related to PD are exposure to pesticides and heavy metals, as well as exposure to some naturally occurring substances (rotenone) or recreational drugs [

2,

8,

9,

10].

Animal models of PD are invaluable tools for understanding the mechanisms underlying the development of this pathology and for testing chemical compounds either inducing or protecting against it. Different zebrafish models of PD, both genetic and chemical, have been proposed, due to the genetic preservation and high homology of the central nervous system found between humans and zebrafish. Specifically related with PD, the dopaminergic system, including both the enzymes involved in the synthesis and degradation of dopamine and the receptors mediating the response to this neurotransmitter, is also highly similar between both species [

11,

12]. Up to date, zebrafish has been successfully used as a model for studying many neurodegenerative diseases, in different life stages – from embryonic to adult individuals [

10,

13]. PD research in zebrafish has been predominantly focused on zebrafish larvae, with increasing interest in the adult zebrafish model in recent years, as the aging interplays as an important factor in PD pathogenesis. To date, a number of chemicals has been applied in order to induce PD-like symptoms in animal models [

14].

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) is a neurotoxic chemical that can be accidentally produced during the synthesis of the opioid analgesic drug desmethylprodine (1-methyl-4-phenyl-4-propionoxypiperidine or MPPP) [

15]. This lipophilic substance easily crosses the blood-brain barrier, leading to a cascade of events finally resulting in dopaminergic neuron degeneration at SNpc and manifestation of motor disfunctions, and as such is one of the most widely used substances to develop chemical models of PD [

5,

16]. Studies focusing on determining PD-like symptoms in adult zebrafish exposed to MPTP are scarce and inconsistent in terms of methodologies. Although most of them reported significant hypokinesia in treated animals [

3,

11,

12,

17,

18,

19], turning disturbance, a relevant motor hallmark symptom of PD affecting the kinematics of the movement, has not yet been determined in MPTP-treated zebrafish yet. Moreover, it is still unclear whether an acute exposure of adult zebrafish to MPTP results in neurodegeneration of dopaminergic neurons or only in a decrease in the dopamine levels [

6]. Finally, no studies are currently available about the suitability of using MPTP-based chemical models of PD in adult zebrafish to reproduce PDP.

In our study we have analyzed some components of the construct and face validity of a MPTP-based chemical model of PD developed in adult zebrafish. First, the effect of an acute (3 days) exposure to this neurotoxic compound on the levels of dopamine and norepinephrine, as well as their main precursors and degradation products has been determined in the brain. Moreover, the expression level of the main genes involved in the synthesis (

th1, th2, dbh), metabolism (mao, comtb), and transport (

slc6a3 and slc18a2) of catecholamines has also been assessed to better understand whether the changes at neurotransmitter level were reflecting regulation or neurodegeneration. Next, the potential hypokinesia of the exposed animals has been evaluated by assessing the basal locomotor activity in the open field test. For the analysis of turning difficulties, the kinematic of the acoustic startle response (ASR) has been analyzed on the automated Zebra_K platform [

20], since during ASR a sharp turn, known as C-bend, is performed [

20,

21]. Finally, in order to assess the presence of PDP, the effect of MPTP exposure on the prepulse inhibition (PPI) has been determined, as a measure of sensorimotor gating.

2. Results

2.1. Acute MPTP Exposure Reduces Brain Catecholamine Levels

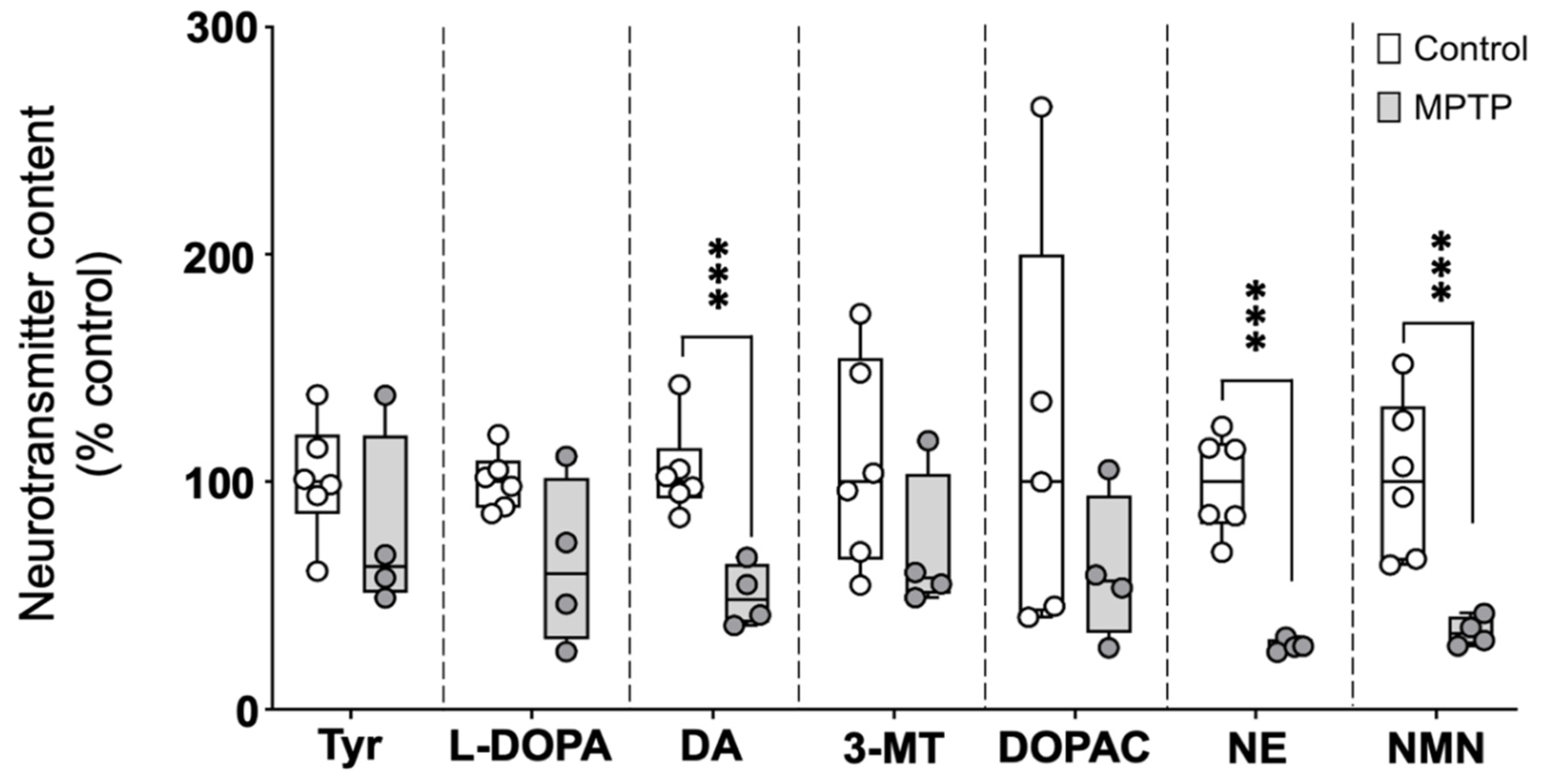

The catecholaminergic neurotransmitters profile was evaluated in brains of control and MPTP-treated fish, 24 h after the three injections. As shown in

Figure 1 and

Supplementary Table S1, brain levels of the catecholamine neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine (NE), as well as the NE metabolite normetanephrine, were significantly reduced in MPTP-treated fish. The observed reductions relative to the control values were 51.8% (IQR: 36.1-62.0%) for dopamine, 72.4% (IQR: 69.2-74.3%) for NE, and 66.9% (IQR: 59.4-71.6%) for normetanephrine [

U(

Ncontrol=6,

NMPTP=4) = 0.0,

z=-2.56,

P= 0.009]. Although the levels of the dopamine precursors (tyrosine and L-DOPA) and metabolites (3-MT and DOPAC) were also lower in MPTP-treated animals compared to controls, in this case the differences were not statistically significant.

2.2. Gene Expression of Catecholaminergic-Related Genes Is Not Altered by MPTP

In order to determine if the acute exposure to MPTP was producing degeneration of the catecholaminergic neurons, the expression of seven genes involved in the synthesis (

th1, th2), degradation (

mao, comtb, dbh) and transport (

slc6a3, slc18a2) of dopamine were determined in the brain of control and MPTP-treated fish. As shown in

Supplementary Figure S1 and

Supplementary Table S2, the expression of none of these genes was significantly altered in the brain 24 hours after the third MPTP injection.

2.3. Acute MPTP Exposure Induces Reversible Hypokinesia

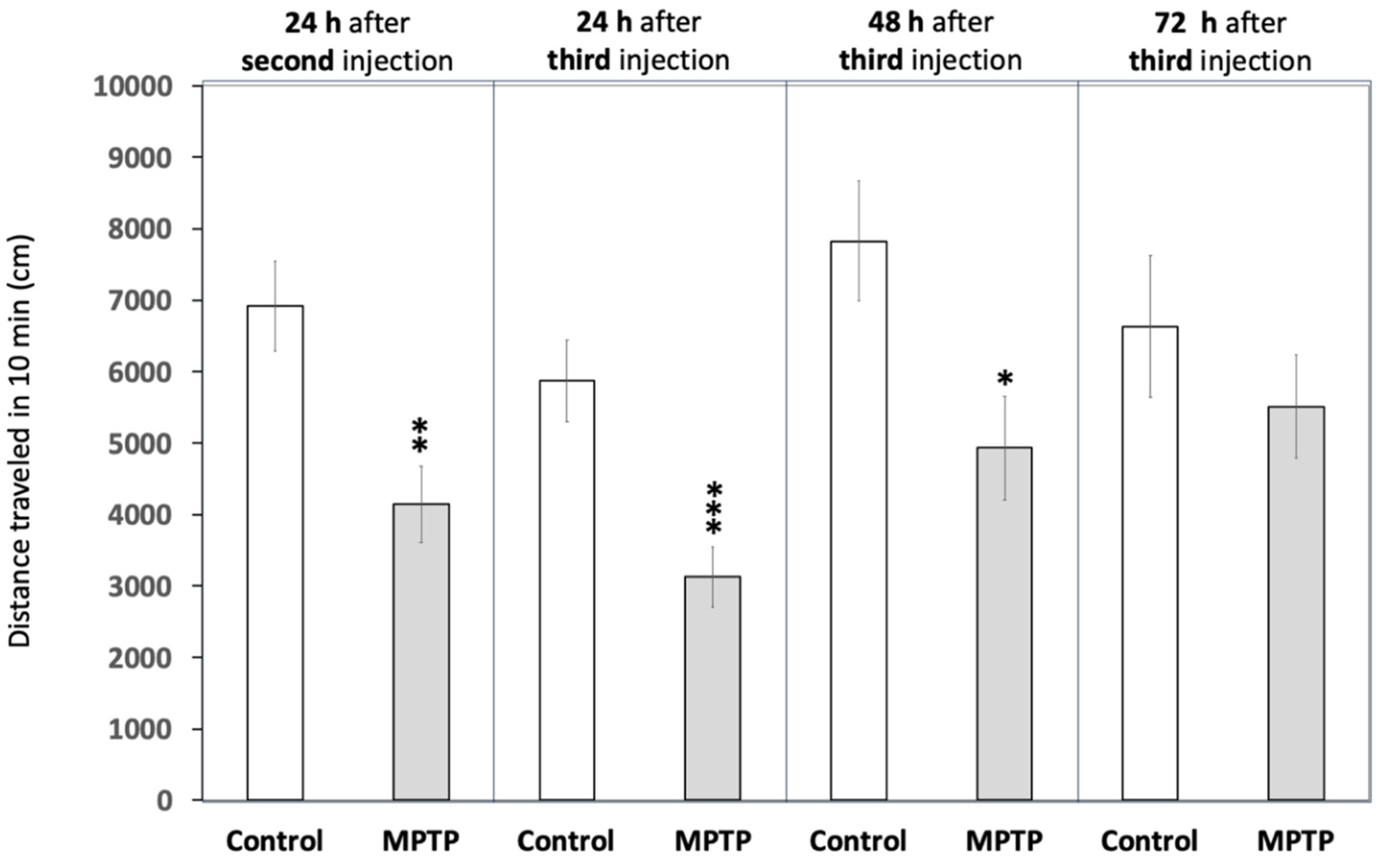

Figure 2 and

Supplementary Table S3 demonstrate that MPTP exposure significantly reduced locomotor activity in the fish, an effect consistent with hypokinesia. Activity decreased to 57.9 ± 6.7% of control values 24 hours after the second injection (

t(45) = 3.941,

P = 0.0016) and further declined to 53.4 ± 7.2% after the third injection (

t(44) = 3.808,

P = 0.00043). To evaluate whether the observed hypokinesia was irreversible, as expected in PD, locomotor activity was also measured at 48 and 72 hours after the final injection. Although still reduced compared to control values, a mild recovery of locomotor activity was observed 48 hours after the third injection (63.0 ± 9.2% of control values;

t(22) = 2.615,

P = 0.0158), with a more pronounced recovery evident at 72 hours (83.1 ± 10.9% of control values;

t(18) = 0.829,

P = 0.418).

2.4. Kinematic Parameters During a Sharp Turn Remain Unaltered After MPTP Exposure

The acoustic startle response (ASR) in adult zebrafish is characterized by a ballistic, short-latency C-bend, providing a unique framework to evaluate whether MPTP exposure induces turning difficulties similar to those characterizing PD. As shown in

Table 1 and

Supplementary Table S4, no statistically significant differences were observed in any of the kinematic parameters between control and MPTP-treated fish. However, the MPTP-treated group exhibited a non-significant trend toward a mild increase in the duration and magnitude of the C-bend. No evidence of loss balance was observed during the C-bend responses.

2.5. Acute MPTP Exposure Leads Sensorimotor Gating Changes Consistent with Psychosis

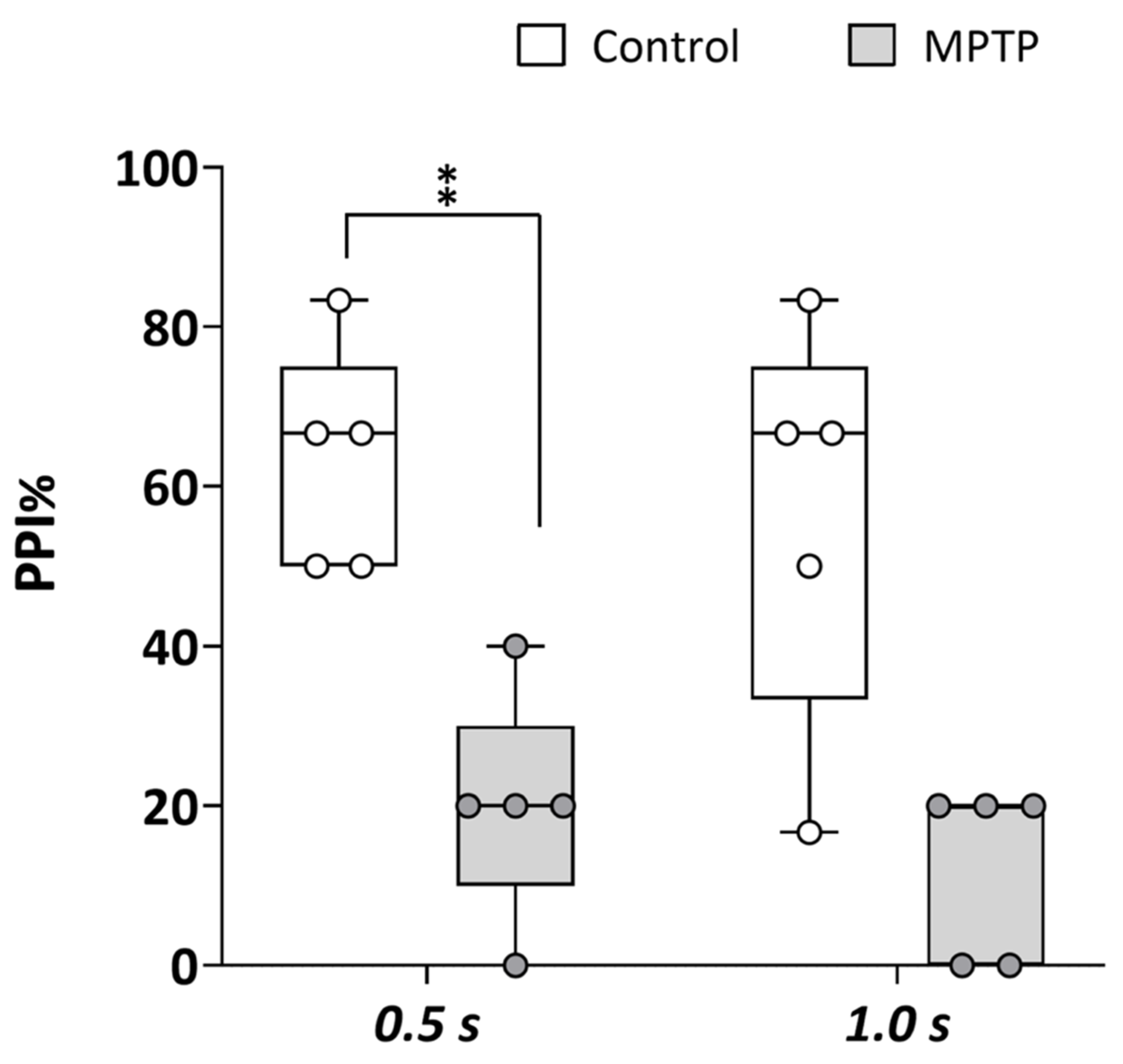

The prepulse inhibition (PPI) paradigm, a well-established measure of sensorimotor gating, is commonly used to assess disruptions in neural processes associated with psychosis. Therefore, to determine if the chemical model of PD developed in adult zebrafish by acute exposure to MPTP presented symptoms of PDP, PPI was analyzed in both control and MPTP-exposed adult zebrafish by using the automated platform Zebra_K. As shown in

Figure 3, a significant decrease in PPI% was evident [

t(8) = 3.776,

P = 0.0054] in the MPTP-treated fish [20% (IQR: 10-30%)] respect to the corresponding controls [67% (IQR: 42-75%)] when the interval between prepulse and pulse was 0.5 s. Although no statistically significant [

U(N

control=5, N

MPTP=5) = 3.9, z = -2.015,

P = 0.056], PPI% was also lower in the MPTP-treated [20% (IQR: 0-20%)] relative to the corresponding controls [50% (IQR: 25-75%)] when the interval between prepulse and pulse was 1 s.

3. Discussion

The current study demonstrates that acute MPTP exposure in adult zebrafish induces significant hypokinesia and decreases brain dopamine and norepinephrine levels. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that zebrafish injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of MPTP exhibit reduced locomotor activity and swimming speed [

3,

11,

18,

22,

23,

24]. Studies that measured brain dopamine content in these models similarly reported significant neurotransmitter depletion [

22,

24]. In addition, a reduction in mobility alongside decreased brain dopamine and norepinephrine levels has been observed in adult zebrafish 24 h after the intramuscular injection of MPTP [

19]. Interestingly, in that study from Anichtchik et al., authors found that despite the observed significant decrease in brain catecholamines 24 h after injection, no effects on catecholaminergic neurons were found by using TH-immunohistochemistry, no changes in the total TH protein were found by western blotting and no signs of apoptosis/necrosis of catecholaminergic neurons were evident by using TUNEL staining and caspase 3 immunostaining and western blotting. All these results are consistent with our finding that despite the significant decrease in brain dopamine and norepinephrine observed 24 h after the last injection of MPTP, the expression of genes involved in catecholamine metabolism (

th1, th2, mao, comtb, dbh) and transport (

slc6a3 and slc18a2) remained unaltered. All these results strongly suggest that the decrease in brain catecholamines found in adult zebrafish after acute exposure to MPTP is not directly related to dopamine neurons degeneration. In fact, in this study it has been shown that the effect of MPTP on locomotion was fully recovered 72 h after injection, further supporting the absence of neurodegeneration in this model. It is also important to consider also that zebrafish is increasingly used as a translational neuroregeneration model, as their stems cell activity is able to re-activate, even in adults, the molecular programs required for a neuronal regenerative response [

25,

26]. Therefore, the remarkable neurogenic and repair capabilities of the adult zebrafish brain may partially counteract MPTP-induced damage.

One important point to discuss about the observed hypokinesia in this model is the fact that it is very well known that either dopamine receptor antagonists or a decrease in dopamine levels decrease locomotor activity in mammals and fish [

27]. Therefore, a phenotype consisting of reduced brain levels of dopamine with concomitant hypokinesia is not specific of PD, as is a common finding in animals exposed to different neuroactive and neurotoxic compounds that decrease the levels of dopamine [

28,

29].

There are aspects of human parkinsonism, such as bradykinesia and tremor at rest, occurring most prominently in appendicular muscle groups, that cannot be conveniently addressed in zebrafish [

27]. However, the difficulty in turning observed in PD patients is a suitable symptom to be determined in zebrafish, as it has been related to axial

rigidity and postural instability. During turning, in contrast to the normal craniocaudal sequence observed in healthy adults, PD patients use an en bloc turning pattern characterized by the simultaneous onset of the axial segment rotation rather than the normal craniocaudal sequence [

30]. To analyze the performance of a sharp turning in adult zebrafish following acute MPTP exposure, we have determined, for the first time, the kinematic parameters during the C-bend of the acoustic startle response. Although no statistically significant differences were observed in any of the kinematic parameters, the MPTP-treated group exhibited a non-significant trend toward a mild increase in the duration and magnitude of the C-bend. Additional efforts should be made to assess this endpoint also in genetic models of PD.

Finally, in this study MPTP-treated fish exhibited a significant decrease in PPI%, consistent with PDP in humans [

7,

31]. A similar reduction in PPI% has been reported in other animal models of PD. While this endpoint was not previously determined in MPTP-treated animals, a significant decrease in PPI% has been reported in 6-OHDA models of PD developed in rats [

32,

33,

34,

35] and mice [

35]. A genetic model of PD in mice, with reduced expression of Nurr1, also exhibited a a significant decrease in PPI% [

36].

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine hydrochloride (MPTP; CAS 23007-85-4) was purchased at Sigma Aldrich (M0896, purity 100%) and dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 15 mg/ml before the start of the experiment.

4.2. Fish Husbandry

Adult zebrafish (standard length: 2.09 ± 0.01 cm) were obtained from Pisciber (Barcelona, Spain). Fish were maintained in zebrafish recirculating system (Aquaneering Inc., San Diego, United States) at the Research and Development Center (CID-CSIC) for two months prior to experiments. Fish were reared in 2.8 L tanks with fish water (reverse-osmosis purified water enriched with 90 mg/L Instant Ocean® [Aquarium Systems, Sarrebourg, France], 0.58 mM CaSO4 · 2H2O, and 0.59 mM NaHCO3), at 28 ± 1°C and 12/12h (light/dark) photoperiod and were fed twice per day with dried food (TetraMin, Tetra, Germany).

4.3. Experimental Design

All applied procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the CID-CSIC (OH 1432/2023) and conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines under a license from the local government (agreement number 9820). For intraperitoneal (IP) injection fish were randomly selected from breeding tanks (average weight 0.40-0.45 g and dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 15 mg/ml before the start of the experiment. g) and subjected to hypothermia for the purpose of anesthetization. Fish were positioned dorsoventrally and each individual was injected 10 µl of the solution per gram of fish into the peritoneal cavity, using a glass Hamilton syringe (10 µL) with ultrafine needle [

37]. Based on the results of the preliminary testing with varying exposure (doses 80-200 mg/kg, 1-3-5 injections) the final experimental set-up was chosen. The total dose of MPTP administered per animal in our study was 450 mg/kg bw, as fish were injected during three consecutive days with 150 mg/kg bw. PBS solution was administered to the control group. Experiments were conducted in triplicates. During the experiments fish were kept in 2.8 L tanks, fed and water was changed daily. Tanks were kept in an acclimatized room at 28 °C with 12/12 h light/dark photoperiod. At the end of experimental period, fish were euthanized by inducing hypothermic shock in ice-cold water, brains were dissected and stored at -80 °C until further analysis.

4.4. Neurotransmitters Assessment

For the extraction of neurotransmitters, their precursors and degradation products from adult zebrafish brain a procedure described in Mayol-Cabré et al. [

38] was followed. This procedure consisted of the homogenization of the samples using a TyssueLyser and subsequent centrifugation and filtration of the supernatant with a 0.22 μm Nylon filter directly into the chromatographic vial.

An internal standard mixture was added to all samples to be able to quantify by means of internal standard calibration curve. Also, quality controls (QCs) were prepared spiking samples with a native standard mixture at a concentration of 5 ppm of the compounds of interest. The QCs were used to evaluate the performed extraction procedure as well.

The solvents used for the extraction were acetonitrile HPLC-MS grade supplied by VWR chemicals (Leuven, Belgium); formic acid LC-MS/MS grade from Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, UK) and ammonium formate from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ultra-pure water was daily obtained from the Millipore Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

Neurochemical analysis was performed by UHPLC-MS/MS. Separation and elution were achieved with the use of a BEH Amide column, and detection was performed in MRM mode with ESI+, guaranteeing specificity in detection and quantification.

To quantify the compounds of interest, a mixture of the following reference standards was used: tyrosine, L-DOPA, dopamine, 3-metoxytyramine (3-MT), 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), norepinephrine (NE), and normetanephrine. These standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Moreover, an internal standard mixture containing DL-norepinephrine-d6 (NE-d6), 3-methoxytyramine-d4 hydrochloride (3-MT-d4) and dopamine-1,1,2,2-d4 hydrochloride (DA-d4) was also used in the quantification. These standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Toronto Research Chemicals (TRC, Toronto, Canada).

4.5. Gene expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from whole brains of control and MPTP exposed adult zebrafish (3 x 150 mg/kg fish bw, 24 h after the last injection) using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), as described elsewhere [

39]. RNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometric absorption in a NanoDrop™️ ND-8000 spectrophotometer (Fisher Scientific). After DNase I treatment (Ambion, Austin, TX), first strand of cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using First Strand cDNA synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and oligo(dT), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Changes in expression of target genes were confirmed by qRT-PCR, performed in a LightCycler ®️ 480 Real-Time PCR System with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Cycling parameters were: 95°C for 15 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C, 10 s and 60°C, 30 s.

Nine biological replicates were analyzed for each group, and three technical replicates were run in parallel for each individual sample.

Primer sequences of the seven selected genes: monoamine oxidase (

mao), tyrosine hydroxylases (

th1 and

th2), dopamine transporter (

slc6a3), dopamine-β-hydroxilase (

dbh), catechol-O-methyltransferase b (

comtb) and vesicular monoamine transporter (

vmat2) as well as the reference gene 2-peptidylprolyl isomerase A (

ppiaa) are listed in

Supplementary Table S5. Efficiency and specificity of all primers were checked before the analyses.

The mRNA expression of each target gene was normalized to the housekeeping

ppiaa. The relative abundance of mRNA was calculated following the ΔΔCt method [

40] deriving fold-change ratios from these values.

4.6. Neurobehavioral Assessment

All behavioral experiments were conducted in a room with controlled environmental conditions (28 °C, darkness), in the timeframe of 10-17h. All fish were acclimated for one hour in the behavioral room prior to testing.

4.6.1. Locomotor Activity

To evaluate a potential hypokinesia in the MPTP-treated fish, the basal locomotor activity was determined by using the open field test, as described elsewhere [

19,

41]. Locomotor assessment was performed 24 h after the second injection (total dose: 300 mg/kg bw) and 24, 48 and 72 h after the third injection (450 mg/kg bw). Briefly, fish were placed in the center of a circular arena uniformly illuminated and recorded for 10 min. Total distance traveled was determined by video tracking analysis, using EthoVisionXT 16 (Noldus, Wageningen, Netherlands).

4.6.2. Kinematic Analysis of the Acoustic Startle Response

Kinematic parameters of a sharp turn, the initial C-bend of the ASR in adult zebrafish, were determined by using the Zebra_K platform, as recently described [

20]. Effects of MPTP on sensorimotor gating were additionally addressed by assessing the pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) in the same platform. Nine experimental arenas were recorded simultaneously (115 ms, 1000 fps) using a high-speed camera (Photron Farcam Mini UX100). The analysis of the videos with the analysis software, provided information on the main kinematic parameters of the initial C-bend: latency, duration (time between the latency and the moment of reaching the maximum bending), curvature (difference between the maximum body curvature during the C-bend and the initial curvature at the latency time), and maximal angular velocity. For PPI analysis, a low-intensity stimuli (1000 Hz, 10 μs and 72.9 dB re 20 μPa), typically eliciting 0–10 % startle responses, was selected for the prepulse, and a startle-inducing stimulus (1000 Hz, 1 ms, 103.9 dB re 20 μPa) was selected for the pulse. A series of 5 prepulse stimuli (interstimulus interval (ISI): 120 s), then a series of pulse stimuli (ISI: 120 s), and finally, a series of 5 sequences “prepulse+pulse” acoustic stimuli (ISI: 120 s) were delivered. For these sequences, the effect of different times between the prepulse and the pulse (0.5 and 1 s) was tested. The PPI percentage was calculated as described elsewhere [

21].

4.7. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS v29 (Statistical Package 2010, Chicago, IL, USA) and data were plotted with GraphPad Prism 9 for Windows (GraphPad software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Normality of the data was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard error (SEM) for parametric data, and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric data. Data from locomotor activity (total distance traveled) and kinematic studies (latency, duration, curvature and maximum angular velocity) were analyzed by unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney test, with regard to the results of normality distribution. Significance was set at P<0.05.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Table S1. Profile of catecholaminergic neurochemicals in the brain of control and MPTP-treated (3 x 150 mg/kg bw. i.p.) adult zebrafish; Supplementary Table S2. Expression profile of tyrosine hydroxylases (th1 and th2), monoamine oxidase (mao), catechol-O-methyltransferase b (comtb), dopamine-β-hydroxilase (dbh), dopamine transporter (slc6a3), and vesicular monoamine transporter (slc18a2) in the brain of control (CN) and MPTP-treated (3 x 150 mg/kg bw. i.p) adult zebrafish; Supplementary Table S3. Total distance (cm) traveled by control (CN) and MPTP-treated adult zebrafish during 10 min in the Open Field Test; Supplementary Table S4. Kinematic parameters of the C-bend during the acoustic startle response in control and MPTP-treated adult zebrafish. Supplementary Table S5. List of primers used for qPCR; Supplementary Figure S1. No significant differences in the expression of catecholaminergic system-related genes 24 h after acute MPTP exposure (3 x 150 mg/kg bw, i.p.).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.R., L.M.G.O., C.G.C; Methodology: N.T., M.S., I.R.A.; Formal Analysis: D.R.; Investigation: N.T., M.S., I.R.A., G.A.E.V., S.E.H.V., E.P.; Resources, D.R., C.G.C.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: D.R., N.T., M.S., I.R.A., G.A.E.V., S.E.H.V., E.P., C.G.C., L.M.G.O.; Writing – Review & Editing: D.R., N.T., M.S., I.R.A., G.A.E.V., S.E.H.V., E.P., C.G.C., L.M.G.O.; Visualization, D.R., M.S.; Supervision, D.R., L.M.G.O., C.G.C.; Project Administration, D.R.; Funding Acquisition, D.R., C.G.C., M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out in the framework of the European Partnership for the Assessment of Risks from Chemicals (PARC) and has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No 101057014. The work was also funded by “Agencia Estatal de Investigación”, from the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2023-148502OB-C21 and C22), by IDAEA-CSIC, Severo Ochoa Centre of Excellence (CEX2018-000794-S), and by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Grant No. 451-03-66/2024-03/200214).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the CID-CSIC and conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines under a license from the local government (agreement number 11336).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript and its Supplementary Material file or will be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, Y.; Rong, Q. Effect of Different MPTP Administration Intervals on Mouse Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2022, 2022, 2112146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease. JAMA 2020, 323, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razali, K.; Mohd Nasir, M.H.; Othman, N.; Doolaanea, A.A.; Kumar, J.; Nabeel Ibrahim, W.; Mohamed, W.M.Y. Characterization of neurobehavioral pattern in a zebrafish 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced model: A 96-hour behavioral study. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0274844–e0274844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.C.; Hsu, W.L.; Wu, R.M.; Lu, T.W.; Lin, K.H. Motion analysis of axial rotation and gait stability during turning in people with Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture 2016, 44, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przedborski, S.; Vila, M. MPTP: a review of its mechanisms of neurotoxicity. Clin. Neurosci. Res. 2001, 1, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, E.; Larsen, J. A review of MPTP-induced parkinsonism in adult zebrafish to explore pharmacological interventions for human Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1451845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, K.; Price, D.L.; Bonhaus, D.W. Pimavanserin, a 5-HT2A inverse agonist, reverses psychosis-like behaviors in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Pharmacol. 2011, 22, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, C.M.; Kamel, F.; Ross, G.W.; Hoppin, J.A.; Goldman, S.M.; Korell, M.; Marras, C.; Bhudhikanok, G.S.; Kasten, M.; Chade, A.R.; et al. Rotenone, paraquat, and Parkinson’s disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.Y.-Y.; Ho, P.W.-L.; Liu, H.-F.; Leung, C.-T.; Li, L.; Chang, E.E.S.; Ramsden, D.B.; Ho, S.-L. The interplay of aging, genetics and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2019, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, J.M.; Croll, R.P. A Critical Review of Zebrafish Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 835827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.A.; Kumar, J.; Teoh, S.L. Parkinson’s disease model in zebrafish using intraperitoneal MPTP injection. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1236049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagwell, E.; Shin, M.; Henkel, N.; Migliaccio, D.; Peng, C.; Larsen, J. 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-treated adult zebrafish as a model for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2024, 842, 137991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babin, P.; Goizet, C.; Raldúa, D. Zebrafish models of human motor neuron diseases: advantages and limitations. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razali, K.; Othman, N.; Mohd Nasir, M.H.; Doolaanea, A.A.; Kumar, J.; Ibrahim, W.N.; Mohamed Ibrahim, N.; Mohamed, W.M.Y. The Promise of the Zebrafish Model for Parkinson’s Disease: Today’s Science and Tomorrow’s Treatment. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 655550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langston, J.W.; Ballard, P.; Tetrud, J.W.; Irwin, I. Chronic Parkinsonism in Humans Due to a Product of Meperidine-Analog Synthesis. Science (80-. ). 1983, 219, 979–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredith, G.E.; Rademacher, D.J. MPTP mouse models of Parkinson’s disease: an update. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2011, 1, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyn, M.; Ekker, M. Cerebroventricular Microinjections of MPTP on Adult Zebrafish Induces Dopaminergic Neuronal Death, Mitochondrial Fragmentation, and Sensorimotor Impairments. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 718244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarath Babu, N.; Murthy, C.L.N.; Kakara, S.; Sharma, R.; Brahmendra Swamy, C. V; Idris, M.M. 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine induced Parkinson’s disease in zebrafish. Proteomics 2016, 16, 1407–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anichtchik, O. V.; Kaslin, J.; Peitsaro, N.; Scheinin, M.; Panula, P. Neurochemical and behavioural changes in zebrafish Danio rerio after systemic administration of 6-hydroxydopamine and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. J. Neurochem. 2003, 88, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevanović, M.; Tagkalidou, N.; Multisanti, C.R.; Pujol, S.; Aljabasini, O.; Prats, E.; Faggio, C.; Porta, J.M.; Barata, C.; Raldúa, D. Zebra_K, a kinematic analysis automated platform for assessing sensitivity, habituation and prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response in adult zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, H.A.; Granato, M. Sensorimotor gating in larval zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 4984–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, V.; Venkatasubramanian, H.; Ilango, K.; Santhakumar, K. A simple method to study motor and non-motor behaviors in adult zebrafish. J. Neurosci. Methods 2019, 320, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretaud, S.; Lee, S.; Guo, S. Sensitivity of zebrafish to environmental toxins implicated in Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2004, 26, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellore, J.; Pauline, C.; Amarnath, K. Bacopa monnieri Phytochemicals Mediated Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles and Its Neurorescue Effect on 1-Methyl 4-Phenyl 1,2,3,6 Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Experimental Parkinsonism in Zebrafish. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, M.; Mariano, V.; Romano, N. Zebrafish as a translational regeneration model to study the activation of neural stem cells and role of their environment. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 30, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambusi, A.; Ninkovic, J. Regeneration of the central nervous system-principles from brain regeneration in adult zebrafish. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, E.A.; Burgess, H.A. A Critical Review of Zebrafish Neurological Disease Models−2. Application: Functional and Neuroanatomical Phenotyping Strategies and Chemical Screens. Oxford Open Neurosci. 2023, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedrossiantz, J.; Bellot, M.; Dominguez-García, P.; Faria, M.; Prats, E.; Gómez-Canela, C.; López-Arnau, R.; Escubedo, E.; Raldúa, D. A Zebrafish Model of Neurotoxicity by Binge-Like Methamphetamine Exposure. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, M.; Ziv, T.; Gómez-Canela, C.; Ben-Lulu, S.; Prats, E.; Novoa-Luna, K.A.; Admon, A.; Piña, B.; Tauler, R.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; et al. Acrylamide acute neurotoxicity in adult zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huxham, F.; Baker, R.; Morris, M.E.; Iansek, R. Head and trunk rotation during walking turns in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fénelon, G.; Alves, G. Epidemiology of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2010, 289, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubser, M.; Koch, M. Prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response of rats is reduced by 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1994, 113, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellenbroek, B.A.; Budde, S.; Cools, A.R. Prepulse inhibition and latent inhibition: The role of dopamine in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 1996, 75, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issy, A.C.; Padovan-Neto, F.E.; Lazzarini, M.; Bortolanza, M.; Del-Bel, E. Disturbance of sensorimotor filtering in the 6-OHDA rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. Life Sci. 2015, 125, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, K.; Price, D.L.; Davis, C.N.; Ma, J.N.; Bonhaus, D.W.; Burstein, E.S.; Olsson, R. AC-186, a selective nonsteroidal estrogen receptor β agonist, shows gender specific neuroprotection in a Parkinson’s disease rat model. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuillermot, S.; Feldon, J.; Meyer, U. Relationship between sensorimotor gating deficits and dopaminergic neuroanatomy in Nurr1-deficient mice. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 232, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.; Cachat, J.M.; Suciu, C.; Hart, P.C.; Gaikwad, S.; Utterback, E.; DiLeo, J.; Kalueff, A. V. Intraperitoneal Injection as a Method of Psychotropic Drug Delivery in Adult Zebrafish. In; 2011; pp. 169–179.

- Mayol-Cabré, M.; Prats, E.; Raldúa, D.; Gómez-Canela, C. Characterization of monoaminergic neurochemicals in the different brain regions of adult zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 141205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.; Bedrossiantz, J.; Ramírez, J.R.R.; Mayol, M.; García, G.H.; Bellot, M.; Prats, E.; Garcia-Reyero, N.; Gómez-Canela, C.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; et al. Glyphosate targets fish monoaminergic systems leading to oxidative stress and anxiety. Environ. Int. 2021, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2 C T Method. METHODS 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.; Fuertes, I.; Prats, E.; Abad, J.L.; Padrós, F.; Gomez-Canela, C.; Casas, J.; Estevez, J.; Vilanova, E.; Piña, B.; et al. Analysis of the neurotoxic effects of neuropathic organophosphorus compounds in adult zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).