1. Introduction

Knee ligament injuries are among the most common musculoskeletal traumas in sports and orthopedics, generally resulting from external forces that exceed the joint’s physiological range of motion or from reduced ligament integrity. Such weakening may occur due to factors including advanced age, prolonged immobilization, systemic disease, corticosteroid use, or vascular insufficiency, making even minor trauma potentially damaging [

1]. Depending on severity, lesions may range from mild stretching to complete rupture, classified as grade I (mild sprain), grade II (partial tear), or grade III (complete rupture). Once weakened, a ligament requires approximately 10 months to regain its mechanical integrity after the removal of the etiological factor. Among these injuries, rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is the most frequent, particularly in young and physically active individuals [

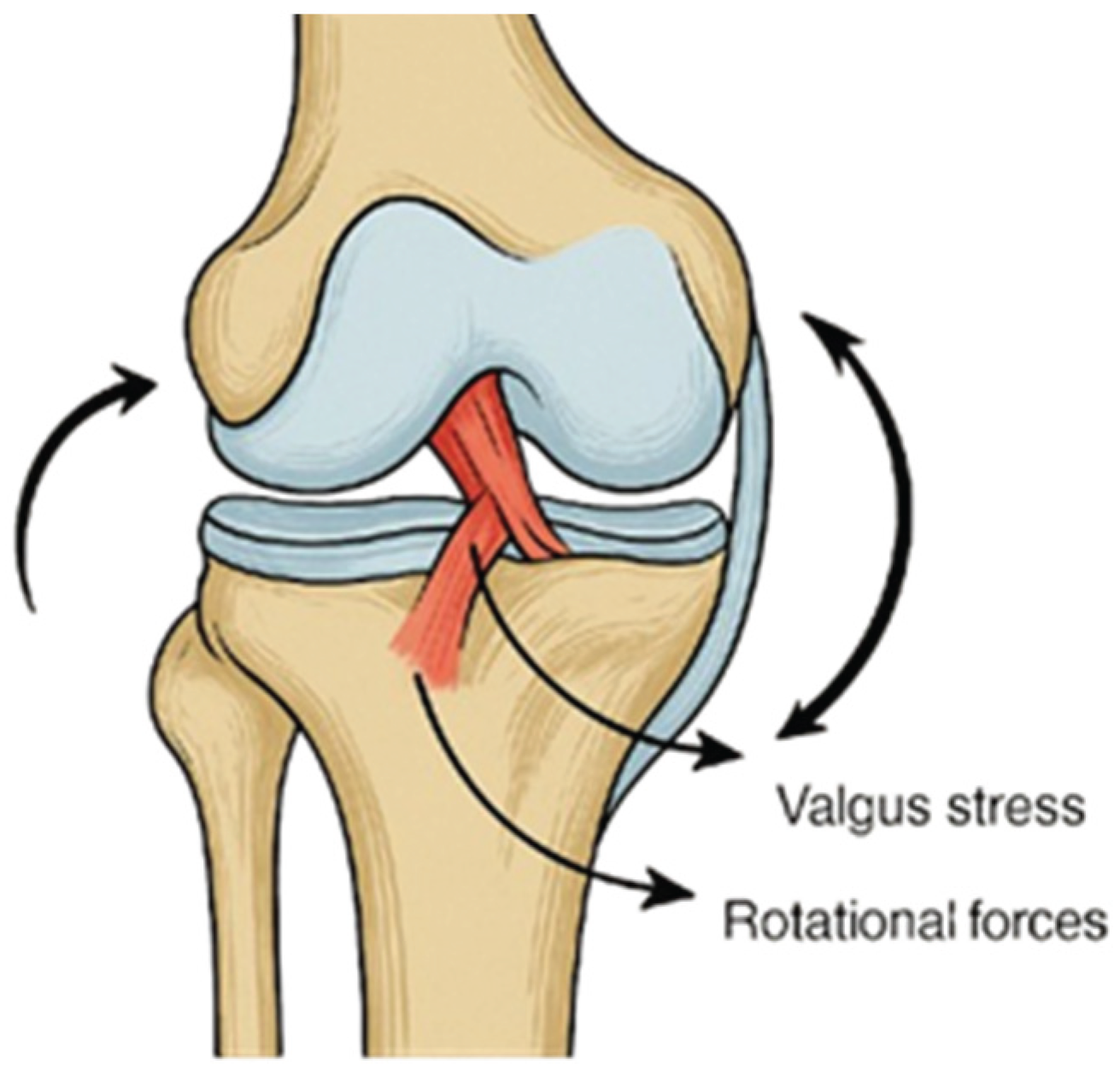

2]. It typically occurs during sports requiring rapid deceleration, pivoting, or direct contact, including soccer, American football, alpine skiing, basketball, etc (see

Figure 1). Anterior cruciate ligament injuries are often associated with concomitant damage to other intra-articular structures, most notably the medial collateral ligament and the medial meniscus, which together constitute the so-called “unhappy triad”. This combined injury pattern not only complicates surgical management but also prolongs rehabilitation, as it further compromises joint stability and functional recovery [

1,

2].

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries are among the most common ligamentous injuries of the knee, particularly in physically active individuals under the age of 65. They are often associated with substantial functional limitations, including pain, swelling, reduced range of motion, muscle hypotrophy, and impaired gait symmetry. Even after surgical reconstruction, many patients experience persistent deficits that may compromise return to activity and long-term joint health [

3].

From a functional perspective, the ACL provides up to 85% of the restraint against anterior tibial translation, and its deficiency results in joint instability, pain, and recurrent “giving way” episodes, particularly during rotational or cutting movements. In addition, secondary changes, such as joint swelling, reduced patellar mobility, and quadriceps inhibition, further limit the range of motion and compromise gait. Consequently, even minor deficits in knee extension can prevent full joint “locking,” altering pelvic alignment, disturbing gait mechanics, and contributing to compensatory strategies such as trunk tilt, pelvic drop, or circumduction. These compensations affect not only the knee but also the hip and ankle, placing additional stress on adjacent joints and increasing the risk of secondary injury [

2,

4].

Therapeutic strategies for ACL rupture vary depending on age, activity level, and severity. While conservative treatment may be considered in older or less active patients, surgical reconstruction is the standard for young and active individuals. Over the years more than 400 reconstruction techniques have been described, with arthroscopic procedures now preferred due to their minimal invasiveness, improved graft placement, and faster recovery [

5]. Autografts, particularly from the patellar tendon or hamstring tendons, remain the gold standard because of their superior biological integration and reduced risk of rejection compared to allografts [

6].

Rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction is therefore a critical component of recovery, with clinical monitoring traditionally relying on measures such as joint range of motion, pain scales, thigh circumference, and swelling. While these tools provide valuable local information about knee function, they do not fully capture the global dynamics of gait recovery. In particular, pelvic symmetry and oscillations during walking reflect the integration of lower limb function into coordinated locomotion, yet remain underexplored in ACL rehabilitation research [

7]. Taken together, ACL injuries represent not only a localized ligamentous disruption but also a broader biomechanical problem that affects lower-limb kinematics, pelvic symmetry, and functional independence. This highlights the need for comprehensive assessment tools that integrate both clinical measurements and modern wearable technologies to better monitor recovery, guide rehabilitation, and optimize long-term outcomes [

1,

3,

8].

Wearable inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensors have emerged as accessible and reliable tools for quantifying spatiotemporal gait parameters and pelvic motion in real-world settings [

9]. When combined with established clinical assessments, IMU-derived data can provide a more comprehensive picture of rehabilitation progress, supporting individualized protocols and potentially improving outcomes [

10].

The present study investigates pelvic oscillations in the sagittal, transverse, and frontal planes during standardized walking in patients undergoing ACL rehabilitation, using pelvic-mounted IMUs in conjunction with clinical assessments of pain, swelling, thigh circumference, and knee range of motion. This integrated approach aims to enhance monitoring precision and to demonstrate the value of technology-supported evaluation in guiding rehabilitation strategies after ACL reconstruction [

11,

12].

The aim of this study was to investigate the recovery of gait dynamics and lower-limb morphometric parameters following ACL reconstruction by integrating pelvic-mounted wearable sensors with established clinical assessment tools during a structured rehabilitation program. By tracking both digital gait biomarkers and conventional clinical metrics, this study sought to provide objective insights into functional recovery and the effectiveness of individualized rehabilitation interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This observational study investigated functional recovery ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon autografts. The study population consisted of 32 individuals (9 women, 23 men; aged 19–64 years) who sought physiotherapeutic and rehabilitative treatment at the University Hospital “Dr. G. Stranski” – Pleven, Bulgaria.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria required patients to have a confirmed ACL injury treated with reconstructive surgery, followed by enrollment in a standardized rehabilitation program progressing from crutch-assisted ambulation to independent walking. Patients were excluded if they were older than 65 years, presented with concomitant severe lower-limb conditions such as multiple ligament ruptures, fractures, advanced osteoarthritis, or had neurological or systemic disorders that could affect gait or had an ACL rupture that had not been surgically treated within a clinically relevant time frame. Individuals who refused or were unable to provide informed consent were also excluded.

2.3. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University – Pleven, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted at the University Hospital “Dr. G. Stranski” – Pleven and adhered to the provisions of Ordinance No. 14 of 27.09.2007, which governs the conditions and procedures for conducting therapeutic and non-therapeutic scientific research involving human subjects in Bulgaria.

All participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the study and provided written informed consent prior to enrollment using a standardized clinical consent form.

2.4. Instrumentation

Pelvic-mounted inertial measurement units (IMUs; G-Walk, BTS Bioengineering, Italy) were used to record three-dimensional oscillations of the pelvis during gait. The device operates at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz, weighs 37 g, and was positioned at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) using an elastic belt, in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Complementary clinical assessments were used to evaluate functional recovery, including knee range of motion (flexion and extension) measured with a goniometer, thigh circumference and knee swelling measured with a centimeter tape, and self-assessed pain intensity using a visual analogue scale (VAS). Together, these instrumentation methods provided a comprehensive assessment of both objective biomechanical parameters and patient-reported functional outcomes, allowing for a detailed evaluation of early recovery following ACL reconstruction.

2.5. Rehabilitation Protocol

The rehabilitation protocol was structured into three progressive phases, spanning the initial five to six weeks after ACL reconstruction. All patients were enrolled in a standardized program, beginning with crutch-assisted ambulation and progressing toward independent gait.

2.5.1. Early Phase (Weeks 1–2)

The primary focus was pain and edema control, restoration of passive and active range of motion, and prevention of muscle atrophy. Patients performed isometric quadriceps contractions, ankle pumps, and straight leg raises in supine position. Assisted knee flexion and extension exercises were introduced gradually, within the pain-free range, using goniometric guidance. Ambulation was carried out with two crutches, with partial weight bearing as tolerated. IMU recordings were synchronized with the initiation of basic gait and joint mobility exercises to track early changes in pelvic stability during crutch-assisted ambulation [

13,

14].

2.5.2. Intermediate Phase (Weeks 3–4)

During this stage, progression to full weight bearing was encouraged, with crutch support maintained until a stable gait was observed. Exercises included closed kinetic chain movements, mini-squats, step training, and resistance-band exercises targeting the quadriceps and hamstrings. Proprioceptive training was introduced through balance-board activities and single-leg stance with external support. Patellar mobilization and soft tissue techniques were applied to reduce residual swelling and enhance joint mobility. Sensor data were used to quantify improvements in pelvic oscillations as patients progressed to full weight-bearing and performed proprioceptive and closed-chain exercises [

14].

2.5.3. Transition Phase (Weeks 4–5)

Patients began walking without assistive devices as stability and confidence improved. Gait training emphasized symmetrical loading and pelvic control. Proprioceptive challenges were advanced through dynamic balance tasks, side-stepping, and light perturbation exercises. Knee flexion typically exceeded 110–120°, allowing for greater exercise variability. By the end of this phase, most patients were able to ambulate independently with minimal gait asymmetry [

13,

14,

15]. IMU measurements captured changes in gait symmetry and pelvic control as patients transitioned to independent walking and more dynamic exercises.

This structured rehabilitation protocol ensured that patients achieved sufficient range of motion, muscle activation, and balance control before discontinuing assistive devices. The program provided a consistent foundation for subsequent evaluation of pelvic oscillations and gait symmetry.

2.6. Data Collection, Management and Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Data Collection

Data collection occurred throughout the rehabilitation period, with particular focus on the transition from crutch-assisted ambulation to independent walking. Assessments were conducted at the start of rehabilitation and finalized around Weeks 5–6, depending on patient progress. Patients performed walking trials along a 10-meter walkway at a self-selected pace (see

Figure 2). IMU data provided digital biomarkers for pelvic oscillations in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes, while clinical evaluations monitored range of motion, muscle hypotrophy, swelling, and pain.

2.6.2. Data Management

All sensor and clinical data were securely recorded in a centralized database. Individual patient data were anonymized to ensure confidentiality. Any missing or inconsistent values were addressed using standard data-cleaning protocols to maintain accuracy and reliability. This multi-modal approach allowed comprehensive monitoring of early functional recovery, integrating quantitative digital metrics from wearable sensors with traditional clinical parameters to reflect the effectiveness of the rehabilitation protocol.

2.6.3. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Raw IMU data were processed using BTS G-Studio software, from which pelvic oscillation indices in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes were extracted. Clinical parameters, including knee range of motion, thigh circumference, knee swelling, and pain scores (VAS), were recorded in a standardized datasheet. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all sensor-derived and clinical parameters. Paired-sample t-tests were performed separately for each plane of pelvic oscillation (sagittal, frontal, and transverse) and for each clinical measure (knee range of motion, thigh circumference, knee swelling, and VAS pain scores) to compare baseline values at the start of rehabilitation with follow-up measurements at Weeks 4–6. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

2.7. Integration of Rehabilitation and Sensor Data

The rehabilitation protocol and sensor measurements were closely coordinated to capture meaningful changes in gait and pelvic dynamics throughout the early recovery period. IMU-derived pelvic oscillations were analyzed in relation to specific rehabilitation milestones, including the transition from crutch-assisted ambulation to independent walking, progression through closed and open kinetic chain exercises, and the introduction of proprioceptive challenges.

This integration allowed quantification of functional improvements in parallel with clinical recovery markers. Changes in pelvic oscillations in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes were compared with knee range of motion, thigh circumference, knee swelling, and pain scores, providing a comprehensive view of the patient’s recovery trajectory. By aligning objective digital biomarkers with structured rehabilitation phases, it was possible to identify the stages at which significant improvements in gait symmetry and stability occurred, supporting evidence-based decisions for individualized therapy progression.

2.8. Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

2.9. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT, OpenAI, GPT-5 Mini) was used exclusively for grammar refinement and organization of ideas in the drafting of this section. All study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation were conducted by the authors.

3. Results

This section presents the outcomes of the rehabilitation process following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, comparing key clinical and gait parameters recorded at two primary time points: initially during crutch-assisted ambulation, and subsequently after patients transitioned to independent walking, typically by Weeks 4–5. The results focus on pelvic motion in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes, as well as complementary clinical parameters including knee range of motion, thigh circumference, knee swelling, and pain intensity, providing an integrated view of functional recovery.

Clinical assessments demonstrated progressive improvement in knee range of motion, reduction in thigh circumference differences, decreased knee swelling, and lower self-reported pain scores across the rehabilitation phases. Sensor-derived pelvic oscillations reflected enhanced gait symmetry and postural control, with gradual reductions in lateral and rotational deviations as patients transitioned from assisted to independent walking. Integration of these data highlights the correspondence between objective biomechanical measurements and traditional clinical recovery markers, demonstrating the effectiveness of the structured rehabilitation protocol in promoting functional mobility and stability.

3.1. Analysis of Pelvic Oscillation in the Sagittal, Frontal, and Transverse Planes after ACL Reconstruction

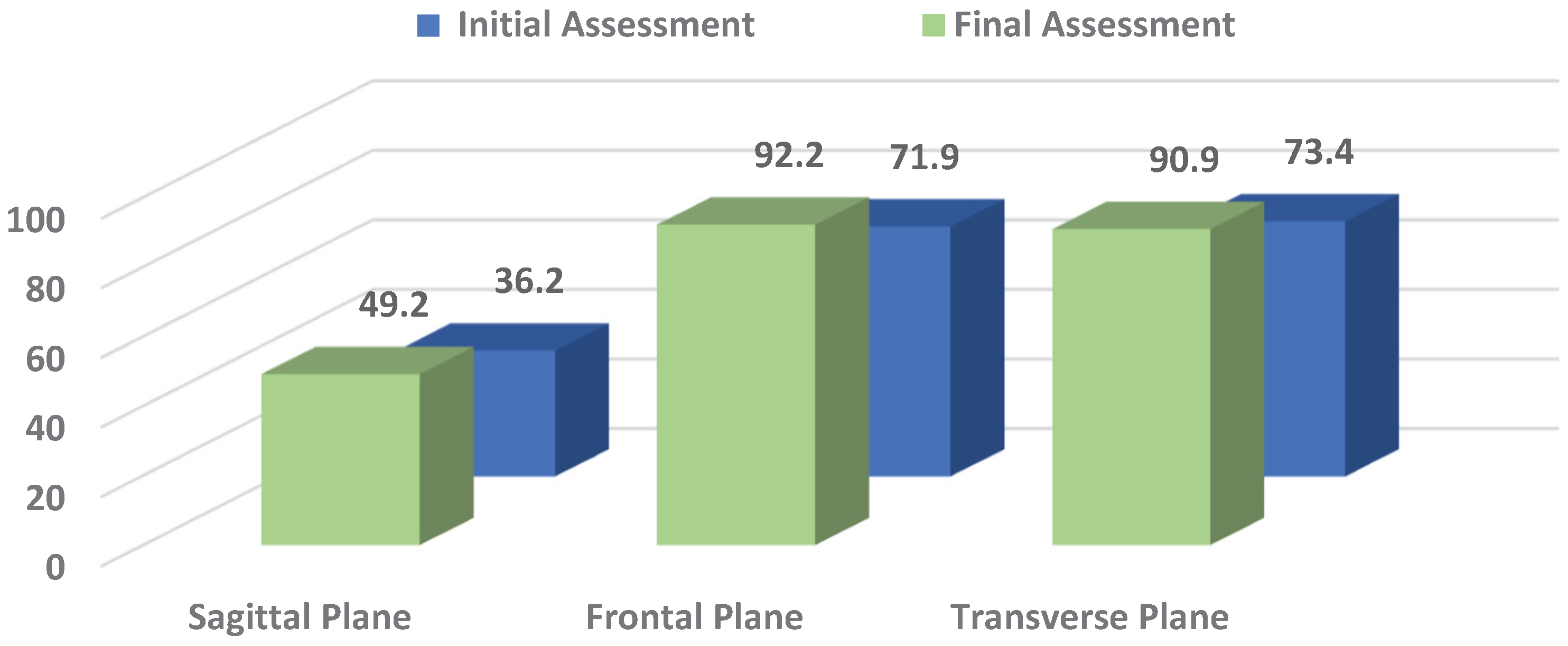

The statistical data on pelvic oscillations in the sagittal (S), frontal (F), and transverse (T) planes are summarized in

Table 1. Values were recorded at two key time points: initially during crutch-assisted ambulation and at the end of the rehabilitation period, when patients had generally achieved independent walking. Pelvic oscillation indices were expressed as percentages (%), reflecting the relative amplitude and symmetry of movement in each plane. These measurements provide an objective assessment of postural control and gait recovery following ACL reconstruction.

From

Table 1 it can be seen that pelvic oscillation at the start of rehabilitation was lowest in the S plane, while values in the F and T planes were comparatively higher. This pattern reflects the typical difficulty patients experience in generating forward propulsion and achieving full knee extension after ACL trauma.

By the end of the rehabilitation period, pelvic oscillations improved across all planes. The most substantial recovery was recorded in the F (p = 0.000) and T planes (p = 0.001), where values approached the normal reference range (100%), reflecting marked gains in lateral stability and rotational control of the pelvis. In contrast, improvement in the S plane, though present, was less pronounced and reached only borderline statistical significance (p = 0.032). This indicates that anterior–posterior control and propulsion remain more challenging to restore during the early stages of recovery.

Overall, these results highlight that rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction leads to significant improvements in pelvic control, particularly in the frontal and transverse planes, while S stability requires longer time and further functional training to normalize (see

Figure 3).

3.2. Knee Range of Motion, Thigh Circumference, and Swelling

The statistical data on knee range of motion (ROM), thigh circumference (TC), and knee swelling (KS) are summarized in

Table 2. Measurements were recorded at two key time points: initially during crutch-assisted ambulation and at the end of the rehabilitation period, after patients generally achieved independent walking. ROM was assessed using a goniometer, while thigh and knee circumferences were measured with a centimeter tape. These clinical parameters provide objective insight into joint mobility, muscle mass preservation, and residual swelling, reflecting the effectiveness of the rehabilitation program.

Table 2 summarizes the clinical outcomes for knee joint mobility, TC, and KS following ACL reconstruction. At baseline, goniometric assessment revealed a combined extension–flexion contracture, with an extension deficit of 9.38° and flexion limited to 61.56°. These restrictions were primarily associated with pain and joint effusion in the immediate postoperative period, despite the brace permitting full extension. By the end of rehabilitation, extension was nearly restored, with only a minimal deficit of 2.03°, while flexion improved to 98.75°, representing approximately 70% of normal values and sufficient for performing basic daily activities.

Initial measurements also demonstrated swelling of 2.88 cm at the knee joint line and quadriceps hypotrophy of 1.13 cm compared with the contralateral limb. The swelling was related to the surgical intervention, while the muscle deficit reflected the effects of immobilization and, in some patients, a prolonged interval between injury and reconstruction. At follow-up, swelling was reduced to 1.09 cm, but quadriceps hypotrophy progressed to 2.53 cm. This indicates that despite the resolution of edema and successful gait recovery without assistive devices, muscle wasting of the quadriceps, particularly the medial head, continued due to reduced loading during the early postoperative phase. Full restoration of muscle bulk typically requires a longer period of progressive weight-bearing and strengthening beyond the initial rehabilitation program.

All differences between baseline and follow-up values reached statistical significance (p < 0.005).

3.3. Pain Intensity

Pain intensity, as self-assessed by patients using a modified visual analogue scale (VAS, 0–20), is summarized in

Table 3. Measurements were recorded at the start of rehabilitation during crutch-assisted ambulation and at the final assessment, after most patients had achieved independent walking. These data provide an important subjective measure of patient comfort and the overall effectiveness of the rehabilitation protocol in reducing pain during early functional recovery.

The modified VAS scores for patients with knee injury and ACL reconstruction are presented in

Table 3. At the start of rehabilitation, the mean pain score was 13.6, indicating substantial discomfort that affected movement. By the end of the observation period, the mean score decreased to 3, reflecting a marked reduction in pain of 77.9% from baseline (p = 0.000). This significant decrease demonstrates the effectiveness of the rehabilitation protocol in alleviating pain and facilitating the recovery of independent gait without the need for assistive devices.

Overall, the results demonstrate progressive improvements across all measured domains of early functional recovery following ACL reconstruction. Pelvic oscillations in the S, F, and T planes showed marked gains, particularly in the frontal and transverse planes, while knee ROM, thigh circumference, and swelling measurements reflected corresponding restoration of joint mobility. Pain intensity decreased substantially, supporting the observed functional gains and highlighting the clinical relevance of the rehabilitation protocol. Together, these findings underscore the value of integrating objective sensor-based assessments with traditional clinical measurements, providing a comprehensive framework for monitoring recovery and enabling more precise, data-driven evaluation of rehabilitation outcomes.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the outcomes of early rehabilitation in patients who underwent ACL reconstruction, integrating traditional clinical measures with objective gait analysis through inertial sensor technology. The combined use of the G-Walk system and standard clinical assessments provided a detailed view of post-operative recovery, emphasizing both the biomechanical and symptomatic aspects of functional improvement [

16,

17].

The analysis of pelvic oscillations revealed distinct recovery patterns across the three anatomical planes. The most pronounced improvements were observed in the frontal and transverse planes, where oscillation values reached the lower limit of the normal range by the end of rehabilitation. These changes indicate a substantial restoration of postural control and symmetry during locomotion. In contrast, the sagittal plane demonstrated a less significant improvement (p = 0.032), which may reflect persistent quadriceps weakness and incomplete normalization of gait mechanics during terminal extension. This finding aligns with previous reports emphasizing that sagittal plane control is the last component to recover following ACL reconstruction due to residual neuromuscular deficits and altered proprioception [

18].

Clinical indicators of recovery followed a similarly positive trajectory. Knee flexion improved markedly, while the extension deficit was reduced to near-normal levels, indicating successful restoration of joint mobility. However, persistent thigh hypotrophy and residual swelling in the knee joint suggest that full muscular recovery requires a longer follow-up period [

19,

20]. These findings are consistent with studies demonstrating that despite restored range of motion, muscle strength and trophic balance often lag behind during early rehabilitation stages [

21].

Pain intensity, as assessed using a simplified version of the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, 0–20), showed a statistically significant reduction, confirming the overall effectiveness of the rehabilitation protocol. The marked decrease in pain not only reflects successful surgical and therapeutic intervention but also facilitates greater engagement in functional exercises and weight-bearing activities, which are essential for achieving optimal motor recovery [

22].

The integration of inertial sensor-based analysis with standard rehabilitation metrics proved particularly valuable for understanding the dynamics of gait recovery. While clinical assessments such as goniometry, circumferential measurements, and VAS provide essential symptomatic and morphological data, wearable technologies offer complementary, quantitative insight into movement quality and interlimb coordination. The ability to objectively track pelvic kinematics enhances the interpretation of functional progress and supports individualized rehabilitation adjustments [

23,

24].

Taken together, these findings highlight that early post-operative rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction leads to significant pain reduction and measurable improvement in gait symmetry and joint mobility, although minor deficits in muscle mass and sagittal control remain. Future research with larger samples and extended follow-up could further clarify the timeline for full biomechanical recovery and the role of digital monitoring in optimizing rehabilitation outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that early rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft leads to significant improvements in pelvic control, knee joint mobility, and subjective pain perception. The observed decrease in pelvic asymmetry and the restoration of sagittal, frontal, and transverse plane oscillations indicate a progressive normalization of gait kinematics during the initial postoperative weeks. Improvements in knee range of motion and reduction in swelling further confirm the positive functional outcomes achieved through a structured, phase-based rehabilitation protocol.

Although mild hypotrophy of the quadriceps muscle persisted in some patients at the end of the observation period, the overall recovery trajectory demonstrated a clear trend toward restored stability and independent ambulation. These results underscore the critical role of early, well-supervised rehabilitation in facilitating safe load-bearing and efficient gait re-education following ACL reconstruction.

Importantly, the integration of wearable inertial measurement units (IMUs) with conventional clinical metrics enhanced the precision of functional assessment by quantifying subtle biomechanical adaptations that may not be fully captured through visual or manual evaluation alone. This hybrid methodology reinforces the value of combining standard physiotherapeutic evaluation with digital motion analysis to monitor rehabilitation progress and individualize treatment strategies.

In summary, the combined use of structured rehabilitation and objective sensor-based assessment represents a promising approach for optimizing functional recovery and improving evidence-based clinical decision-making in postoperative knee rehabilitation.

6. Patents

The present study utilized a commercially available inertial sensor system (G-Walk, BTS Bioengineering, Italy) for gait analysis. No patents or patent applications were generated from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.D. and D.E.V.; methodology, A.K.D.; software, A.K.D.; validation, A.K.D. and D.E.V.; formal analysis, D.E.V.; investigation, A.K.D.; resources, A.K.D.; data curation, A.K.D.; writing original draft preparation, A.K.D.; writing review and editing, D.E.V.; visualization, A.K.D.; supervision, D.E.V.; project administration, A.K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Medical University – Pleven, Bulgaria, under research project № 5/2023, which provided support for the acquisition of the inertial sensor.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Pleven. Approval was granted under institutional procedures related to project 5/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions related to patient confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Medical University of Pleven for providing the inertial sensor equipment crucial to this research. We also extend our sincere thanks to the university staff for their valuable technical support during data collection. Special appreciation is given to the funding provided through MU-Pleven research project № 5/2023, which facilitated the acquisition of the G-WALK sensor system employed in this study.

The present study is part of the doctoral dissertation recently defended by Atanas Drumev at the National Sports Academy “Vassil Levski” in Sofia.

This research is supported by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the national program "Young Scientists and Postdoctoral Students - 2."

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-4) for refining language and organization. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACL |

Anterior Cruciate Ligament |

| F |

Frontal |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurement Unit |

| KS |

Knee Swelling |

| ROM |

Range Of Motion |

| S |

Sagittal |

| T |

Transverse |

| TC |

Thigh Circumference |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

References

- Tolan, G.A.; Raducan, I.D.; Uivaraseanu, B.; Tit, D.M.; Bungau, G.S.; Radu, A.-F.; Furau, C.G. Nationwide Epidemiology of Hospitalized Acute ACL Ruptures in Romania: A 7-Year Analysis (2017–2023). Medicina 2025, 61, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo-Ortíz, N.K.; Sigala-González, L.R.; Ramos-Moctezuma, I.R.; Bermúdez Bencomo, B.L.; Gomez Salgado, B.A.; Ovalle Arias, F.C.; Leal-Berumen, I.; Berumen-Nafarrate, E. Standardizing and Classifying Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: An International Multicenter Study Using a Mobile Application. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motififard, M.; Akbari Aghdam, H.; Ravanbod, H.; Jafarpishe, M.S.; Shahsavan, M.; Daemi, A.; Mehrvar, A.; Rezvani, A.; Jamalirad, H.; Jajroudi, M.; Shahsavan, M. Demographic and Injury Characteristics as Potential Risk Factors for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: A Multicentric Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptaszyk, O.; Boutefnouchet, T.; Cummins, G.; Kim, J.M.; Ding, Z. Wearable Devices for the Quantitative Assessment of Knee Joint Function After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury or Reconstruction: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoepp, C.; Tennler, J.; Praetorius, A.; Dudda, M.; Raeder, C. From Past to Future: Emergent Concepts of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery and Rehabilitation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, F.; Rovere, G.; Giustra, F.; Masoni, V.; Cassaro, S.; Capella, M.; Risitano, S.; Sabatini, L.; Lucenti, L.; Camarda, L. Advancements in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair—Current State of the Art. Surgeries 2024, 5, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hušek, F.; Vitvar, J.; Mizera, R.; Horák, Z.; Čapek, L. Gait Analysis After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery Comparing Primary Repair and Reconstruction Techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneva-Georgieva, N.; Paskaleva, R. Integral rehabilitation for traumatic injuries of the stifle joint complex in the early recovery period. Knowledge International Journal 2021, 45(4), 861–866. [Google Scholar]

- Muro-de-la-Herran, A.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; Mendez-Zorrilla, A. Gait Analysis Methods: An Overview of Wearable and Non-Wearable Systems, Highlighting Clinical Applications. Sensors 2014, 14, 3362–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Lin, W.; He, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M. IMU-Based Motion Capture System for Rehabilitation Applications: A Systematic Review. Biomimetic Intelligence and Robotics 2023, 3, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayalapra, S.; Wang, X.; Qureshi, A.; Vepa, A.; Rahman, U.; Palit, A.; Williams, M.A.; King, R.; Elliott, M.T. Repeatability of Inertial Measurement Units for Measuring Pelvic Mobility in Patients Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty. Sensors 2023, 23, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Hogen, C.A.; Miller, E.J.; Kaufman, K.R. Validation of Pelvis and Trunk Range of Motion as Assessed Using Inertial Measurement Units. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmel, C.; Krutsch, W.; Szymski, D.; Pfeifer, C.; Henssler, L.; Frankewycz, B.; Angele, P.; Alt, V.; Koch, M. Current Standards of Early Rehabilitation after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in German Speaking Countries—Differentiation Based on Tendon Graft and Concomitant Injuries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneva-Georgieva, N. Proprioceptive training following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Trakia Journal of Sciences 2024, 22(4), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, D.; Ambrosio, L.; Za, P.; Maltese, G.; Russo, F.; Vadalà, G.; Papalia, R.; Denaro, V. Effective Prevention and Rehabilitation Strategies to Mitigate Non-Contact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-S.; Jang, S.-H.; Cho, J.-S.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, H. D.; Lee, S. Y.; Moon, S.-B. Evaluation of validity and reliability of inertial measurement unit-based gait analysis systems. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2020, 42, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Park, H.; Bonato, P.; Chan, L.; Rodgers, M. A review of wearable sensors and systems with application in rehabili-tation. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessi, G.C.; Serrão, F.V. Effects of Fatigue on Lower Limb, Pelvis and Trunk Kinematics and Lower Limb Muscle Activity During Single-Leg Landing After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 2550–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelbourne, K.D.; Benner, R.; Gray, T.; Bauman, S. Range of Motion, Strength, and Function After ACL Reconstruction Using a Contralateral Patellar Tendon Graft. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2022, 10, 23259671221138103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Efficacy of Repair for ACL Injury: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Sports Med. 2022, 43, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, J.T.; Powers, M. ACL Rehabilitation Progression: Where Are We Now? Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2017, 10, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oztekin, H.H.; Boya, H.; Ozcan, O.; Zeren, B.; Pinar, P. Pain and Affective Distress Before and After ACL Surgery: A Comparison of Amateur and Professional Male Soccer Players in the Early Postoperative Period. Knee 2008, 15, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, A.J.; Saatchi, R.; Ward, O.; Nwaizu, H.; Hawley, D.P. Proof-of-concept study of the use of accelerometry to quantify knee joint movement and assist with the diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Technologies 2022, 10(4), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obukhov, A.; Volkov, A.; Nikitnikov, Y. Development of a mobile application for musculoskeletal rehabilitation based on computer vision and inertial navigation technologies. Technologies 2024, 12(12), 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).