1. Introduction

The relationship between agriculture and electronics is often narrated through the lens of digital transformation, and more recently big data, AI, and IoT (Internet-of-Things) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, both beneath and above this computational layer exist two pivotal interfaces that make possible the interaction between digital systems and the non-digital domains. One of these layers encompasses the continuous substrate of analog circuitry responsible for transducing natural physical phenomena (such as light intensity [

11], temperature [

12], soil moisture [

13], ionic concentration [

14], and pH [

15]) into measurable electrical signals. Conversely, the other layer involves the utilization of electronic systems to actuate physical processes, such as those employed in weed management [

16] and control systems. Without these analog interfaces, the so called “digital” farms would be incapable of perceiving or interacting with the environment.

From the 1950s through the early 1980s, agricultural instrumentation evolved primarily through analog signal processing. Bridge circuits, op-amp-based amplifiers, Wheatstone networks, and RC feedback systems were used to condition transducer signals for irrigation control, greenhouse automation, and soil monitoring [

18]. These technologies laid the foundation for closed-loop control long before digital microcontrollers were available. Indeed, analog control loops remain vital today, particularly in rural contexts where cost, robustness, and low power consumption outweigh the benefits of high-level computation [

19,

20].

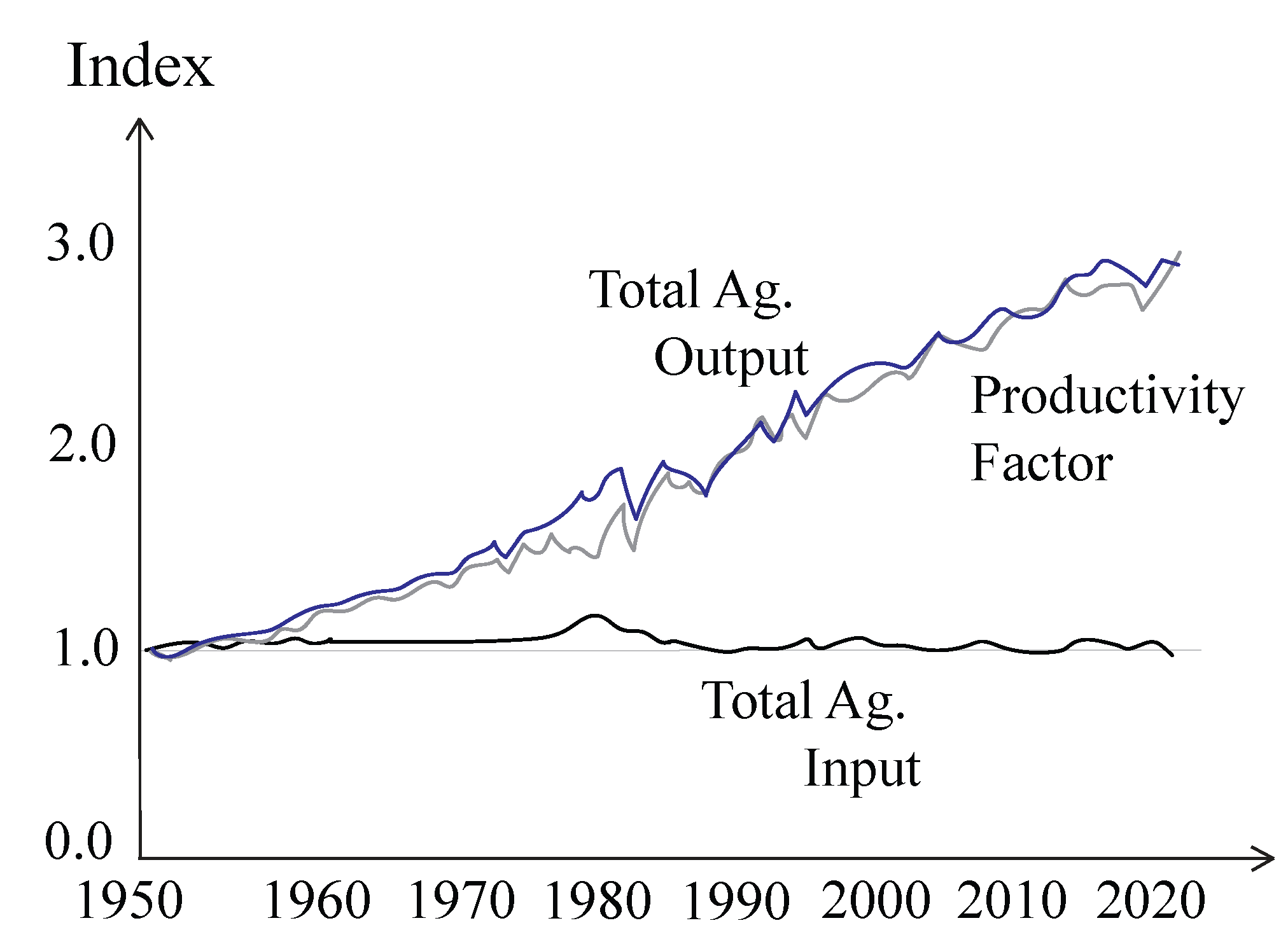

Figure 1 shows that despite relatively constant total input levels, agricultural output has nearly tripled since the mid-twentieth century. This divergence reflects the steady rise in total factor productivity (y-axis, i.e., Index in

Figure 1), an aggregate measure capturing technological progress, which was for some extent enabled by analog electronics that played an important role advancing mechanization, electrification, sensing, digital electronics and automation. Source: USDA, Economic Research Service,

Agricultural Productivity in the U.S. Data Product, data as of January 2024. [

21].

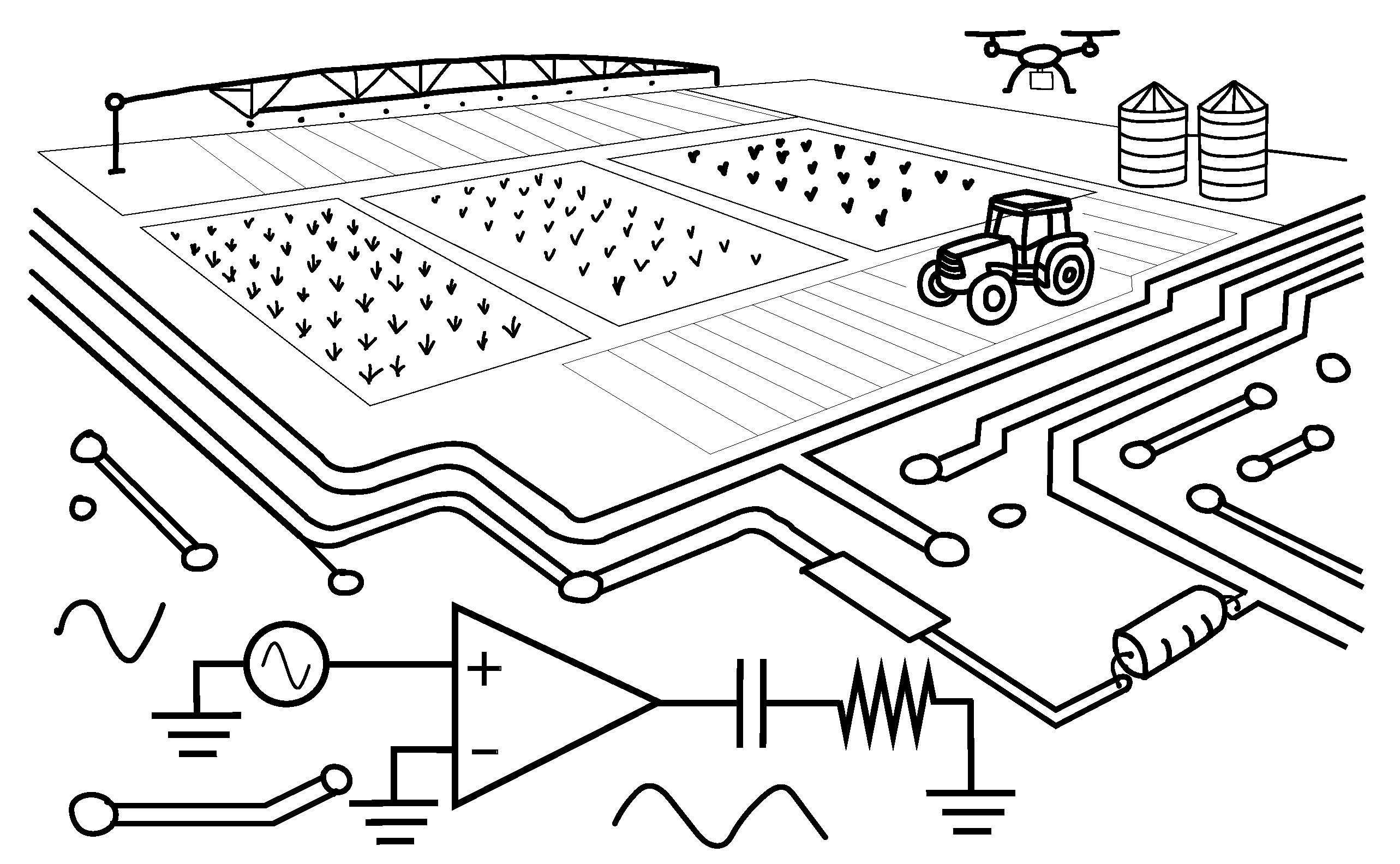

This state-of-the-art paper re-centers analog electronics as a central enabling technology of modern agricultural porcesses, as shown schematically in

Figure 2, which visually merges the imagery of a cultivated landscape with the structure of an electronic circuit board. The figure suggests that beneath every agricultural process (from sensing soil conditions to powering irrigation) there exists an electronic substrate where analog signals continuously interact with natural phenomena to enable intelligent and responsive cultivation. This paper highlights key milestones in (i) electroculture and plant-response circuits, (ii) analog sensing and instrumentation amplifiers, (iii) analog signal conditioning in environmental and soil monitoring, (iv) electronics for energy conversion and actuation, and (v) hybrid analog-digital architectures for resource-constrained precision agriculture.

2. Historical Evolution of Analog Electronics in Agriculture

2.1. Early Electroculture and Electrical Plant Stimulation

The first experiments linking electricity and plant growth date back to Pierre Bertholon de Saint-Lazare in the 18th century, who hypothesized that atmospheric electricity influenced crop vigor [

22]. Subsequent 19th-century investigations by Lemström and Lodge tested high-voltage electrostatic fields on crop productivity. Although the mechanisms were poorly understood, they established the conceptual foundation for what was known as electroculture, i.e., the direct application of electrical energy to plants or soil [

23,

24].

By the early 20th century, field researchers employed spark-gap generators, Wimshurst machines and variable transformers to impose high-voltage electrostatic or oscillatory fields on crops. A 2021 review by Christianto and Smarandache collated early work on electroculture [

25], while a 2025 controlled study by Chier et al. demonstrated that passive antenna- or rod-based methods (e.g., copper-wrapped dowels) show no consistent yield benefit, thereby emphasising the need for actively controlled electrical stimulation systems to generate reliable plant responses [

26].

2.2. Analog Measurement of Soil and Water Properties

Analog circuits found their first enduring agricultural home in soil and irrigation management. Resistance-type tensiometers and capacitance-based probes became the earliest soil moisture sensors [

27]. These pioneer devices relied on Ohm’s and Kirchhoff’s laws (i.e., analog principles) to translate water content into measurable resistance or dielectric changes. Phene and Howell (1984) later integrated such sensors into feedback controllers for automated irrigation [

28].

Time-domain reflectometry (TDR) extended this into the electromagnetic domain, exploiting the propagation velocity of analog pulses in coaxial lines to infer soil permittivity. Though now often digitized, TDR’s foundation remains analog, rooted in signal reflection and impedance matching [

29].

In essence, resistive sensors monitor soil conductivity through current flow, capacitive sensors infer moisture from dielectric behavior under alternating fields, and TDR systems extend this concept into the electromagnetic time domain, timing analog pulse reflections to quantify permittivity with high precision. While modern implementations often digitize the signal, the underlying physics of all three remains inherently analog, rooted in the continuous interaction between electric fields and the soil–water matrix. A summary of the main characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

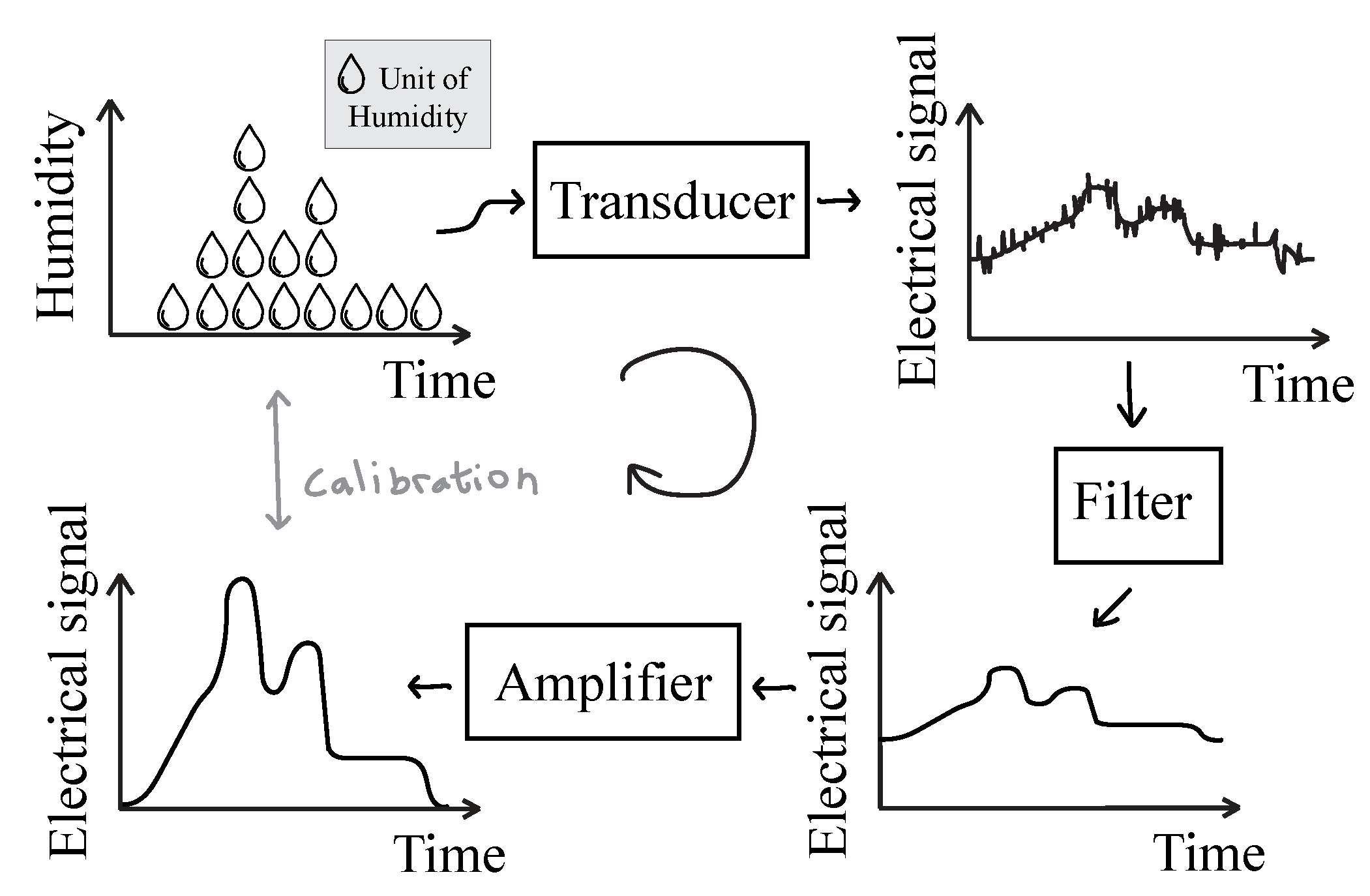

Regardless of the technology employed, i.e., resistive, capacitive, or TDR,

Figure 3 presents a block diagram illustrating the operational principles of these sensors. This figure illustrates an analog sensing and signal-conditioning chain for a humidity measurement example. Notice that the physical variable (humidity vs. time, upper left) is converted by a transducer into a low-level electrical signal (upper right) that is contaminated by noise and interference. An analog filter attenuates high-frequency components and drift (right, middle→bottom), yielding a smoother waveform that preserves the underlying dynamics of the original variable (i.e., humidity). The conditioned signal is then amplified (bottom left) to a level appropriate for subsequent digitization or thresholding. A bidirectional “calibration” link indicates the required mapping between the physical domain and the electrical domain (gain, offset, linearization), highlighting that transducer characteristics and downstream conditioning must be tuned together and periodically re-verified.

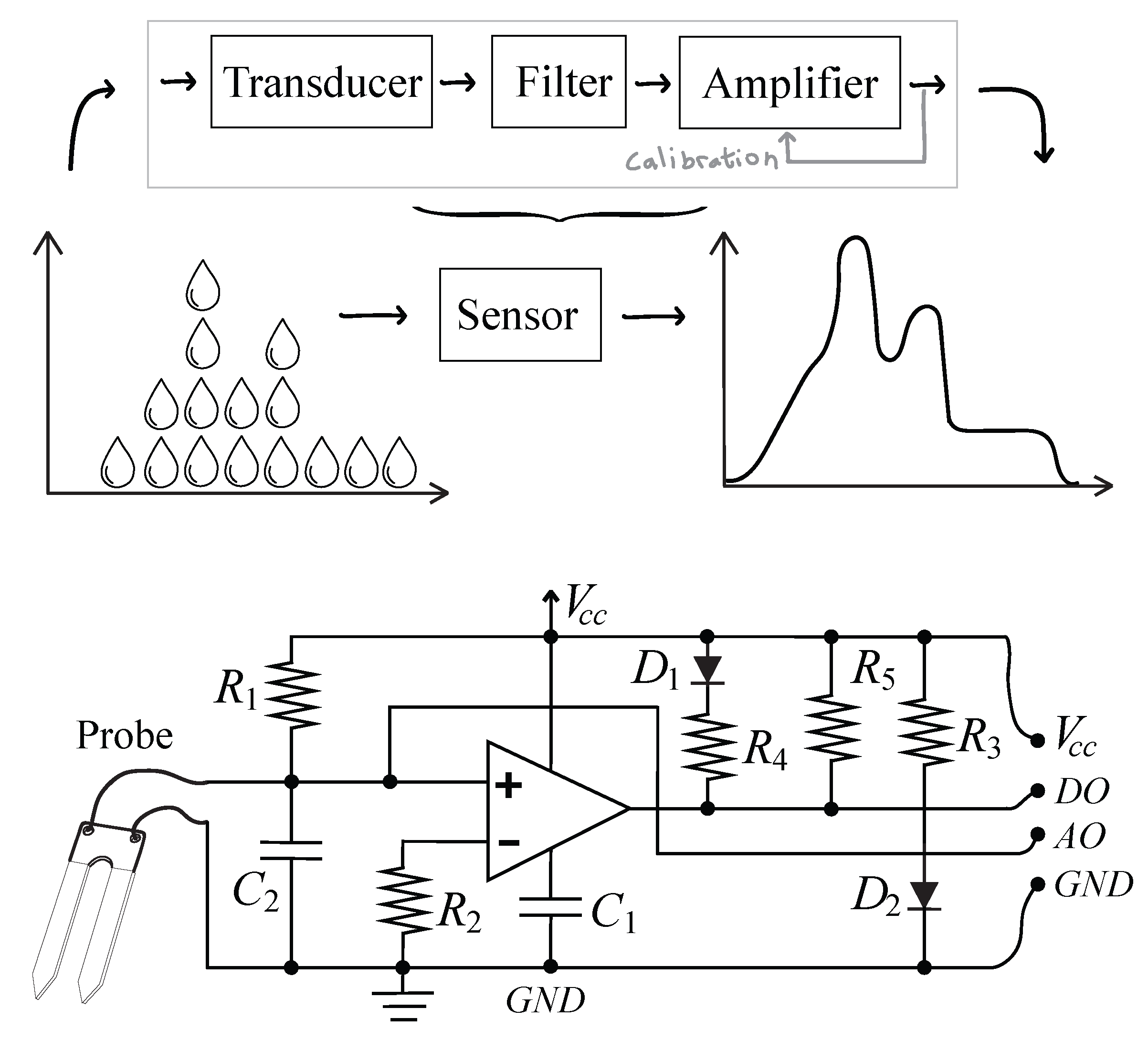

All the blocks shown in

Figure 3 (namely the transducer, filter, and amplifier) together constitute what is referred to as the sensor, as shown in

Figure 4 (top).

Figure 4 (bottom) shows a typical circuit representing the analog front-end of a soil moisture sensor based on the LM393 comparator. The two soil probes act as a variable resistor whose resistance decreases as moisture increases, producing a voltage that reflects soil humidity. The LM393 compares this probe voltage with a fixed reference set by resistors R1 and R2. When the sensed voltage crosses this threshold, the comparator switches its output, providing a binary signal that distinguishes between “wet” and “dry” conditions. The surrounding components stabilize and condition the signal. Resistors R3–R5 set current limits and pull-up levels, while capacitors C1 and C2 filter electrical noise, ensuring smooth transitions and preventing false switching. Diodes D1 and D2 serve as indicator LEDs: one shows the output state, and the other confirms power. The circuit produces both a digital output (DO), used for triggering irrigation or control systems, and an analog output (AO), which varies continuously with soil moisture and can be read by a microcontroller.

2.3. Early Feedback Control In Agriculture

Feedback control is fundamental in maintaining the stability and precision of dynamic systems by continuously regulating a specific variable toward its desired value [

30]. In this mechanism, a system’s output is fed back and compared with a reference input; any deviation between the two generates an error signal that drives the controller to counteract the disturbance. This process effectively minimizes fluctuations, ensuring the controlled variable, such as temperature, voltage, or motor speed, remains within acceptable limits despite external or internal perturbations [

31].

Early greenhouse climate regulation relied on continuous-time, analog feedback loops built from comparators, op-amps, and relay/triac power stages. Thermostats, humidistats, and CO2 controllers produced error signals (setpoint minus measured value) that drove proportional or PI actions to actuate vents, heaters, fans, and CO2 valves. Historical surveys and handbooks document the evolution from such analog loops to supervisory computers/PLCs layered on top, while sensors and power actuation remained essentially analog in their interface and energy delivery.

Irrigation offered some of the earliest, clearest examples of closed-loop control using analog transduction. For instance, tensiometers coupled to pressure transducers produced an analog voltage proportional to soil water tension; that signal was compared to setpoints to switch pumps/valves, creating a feedback loop on substrate water potential. Seminal horticultural studies by Lieth and Burger (1989) [

33] and Kiehl, Lieth and Burger (1992) [

34] used automated (computer-supervised) but fundamentally analog-sensed control to maintain prescribed moisture regimes; a later review by Shock (2011) explicitly notes that tensiometer + transducer systems were successfully used to automate greenhouse irrigations, evidencing the durability of analog feedback in practice [

35].

3. Analog Front-Ends, Signal Conditioning, and Energy Systems for Agricultural Sensing

3.1. Sensor Interfacing

As mentioned before, modern precision agriculture relies on accurate analog front-ends (AFEs) to bridge the physical domain of transducers with the computational world of microcontrollers and digital processing units. In these systems, analog electronics perform the essential task of converting original variables from electrochemical, photometric, or capacitive sensors (among other types of signals) into measurable voltages or currents that can be faithfully digitized [

36].

Among early implementations, ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) demonstrated the indispensable role of analog circuitry in field chemistry. Munter’s pioneering work in the 1980s showed that reliable determination of ionic species such as nitrate, ammonium, and potassium in soil extracts required high-impedance amplifier stages and stable reference potentials to prevent drift and polarization errors in electrode measurements. These analog front-ends maintained linearity and precision even when the sensed potentials were on the order of microvolts and the currents were in the nanoampere range, which are levels that remain below the resolution of purely digital devices [

37]. More recently, Riedel et al. (2024) developed ISFET-based measurement modules for in-field nutrient analysis that still rely on analog buffers and transimpedance amplifiers for reliable potentiometric readouts, underscoring the continued importance of analog interfaces in agrochemical sensing [

40].

Similarly, chlorophyll meters introduced by Monje and Bugbee (1992) integrated analog photometric circuits to quantify leaf greenness based on optical transmission and absorption. Their design relied on transimpedance amplifiers and analog filters to convert low-level photocurrents into usable voltages while minimizing noise, emphasizing that signal conditioning must occur in the analog domain before any digital sampling or processing [

38]. Subsequent designs, such as the low-cost chlorophyll meter developed by Kamarianakis et al. (2023), continue this principle, embedding analog current-to-voltage converters and LED driver circuits within modern sensor nodes to maintain accuracy under fluctuating light conditions [

39].

Analog measurement techniques also remain central in the development of soil conductivity and permittivity sensors. For instance, Song and Zhang (2024) presented an in-situ soil electrical conductivity sensor that employs a precision analog front-end (Analog Devices AD5941) to measure impedance variations caused by changing ion concentrations, combining high-resolution analog circuitry with digital calibration routines [

41].

Even as data-acquisition systems migrate toward embedded microcontrollers and wireless nodes, the front-end interface (responsible for impedance matching, noise suppression, and transduction linearity) remains fundamentally analog. This technological continuity illustrates a recurring need across decades of agri-electronic development: digital precision is only as reliable as the analog circuitry that precedes it.

3.2. Amplifiers, Filters, and Converters

Instrumentation amplifiers (INAs) remain the default front end for low-level agricultural transducers because they provide precise gain set by often changing a single resistor, and excellent common-mode rejection (CMRR) in the presence of large ground shifts along long field cables, and high input impedance. Three-op-amp IN topologies are preferred for bridge-type sensors (e.g., load/pressure cells for axle weight, sap flow, or soil compaction) and for differential electrochemical probes, where millivolt-level signals must be extracted in the presence of tens to hundreds of millivolts of common-mode and substantial line-induced noise. Practical implementations must control input bias currents and 1/ƒ noise; modern auto-zero/chopper-stabilized architectures suppress offset and drift to the microvolt range without sacrificing low-frequency fidelity, which is critical for slowly varying agro-environmental signals, i.e., nutrient concentration [

42].

Analog filtering remains essential even as ADC resolutions and oversampling ratios. Field wiring can behave like an antenna that couples narrowband and broadband RF interference from pumps, inverters, and radios. Accordingly, most nodes employ active low-pass anti-alias filters, typically Sallen–Key or multiple-feedback topologies, placed ahead of the converter to band-limit the signal and to provide out-of-band attenuation commensurate with the ADC’s sampling rate. For multiplexed sensor hubs, unity-gain buffers are added to isolate the filter from channel-to-channel loading and to drive the sampler/hold capacitance of successive-approximation (SAR) converters without settling errors. Where delta–sigma ADCs are used, their internal digital filtering does not obviate the need for an external analog RC: a modest pre-filter reduces wideband EMI and prevents out-of-band energy from folding into the passband through nonidealities [

45,

46]. Input protection (series resistors, TVS diodes) and RC “RF stop” networks at each INA input are also standard practice to tame conducted and radiated emissions on multi-meter cables while keeping thermal noise low.

Converter selection is dictated by signal dynamics and power budget. SAR ADCs paired with dedicated ADC driver amplifiers are favored for multi-channel soil and climate nodes requiring deterministic latency and moderate sample rates (kS/s), whereas delta–sigma converters excel in high-resolution, low-bandwidth measurements such as pH, EC, and weigh-scale signals with intrinsic 1/ƒ content. In both cases, reference quality is as important as the converter core: low-noise, low-drift voltage references (with proper decoupling and Kelvin connections) set the absolute accuracy of nutrient-probe and chlorophyll-meter measurements [

46]. Finally, because many agricultural instruments must operate from solar-battery supplies, amplifiers are frequently chosen for rail-to-rail operation and nanoamp-to-microamp quiescent currents while maintaining noise densities below a few nV/sqrt(Hz); chopper techniques allow these goals without periodic field recalibration [

42,

43]. In sum, robust analog front ends—INAs that reject common-mode contamination, filters that set the measurement bandwidth, and converters matched to signal statistics are indispensable to transform fragile transducer outputs into data of metrological quality in harsh farm environments [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

3.3. Analog Biosensing and Plant Physiology

Analog front-ends are increasingly applied to bioimpedance and plant electrophysiology, extending agricultural electronics from soil and environmental sensing to the plant itself. Variable-frequency excitation circuits measure the complex impedance of stems and leaves to infer changes in intracellular water and ion transport, providing indicators of water stress and nutrient status [

47,

48,

49]. Lock-in amplifiers and synchronous demodulators isolate the small in-phase and quadrature components of these signals, enabling high-fidelity impedance spectroscopy under noisy field conditions.

In plant electrophysiology, analog amplifiers record endogenous voltage changes triggered by mechanical or light stimuli. Such bioelectrical potentials, often in the microvolt range, require ultra-low-noise instrumentation amplifiers and sub-hertz active filters to prevent drift and interference [

50,

51,

52,

53]. These circuits permit the observation of slow action potentials and signaling waves that reveal stress responses and systemic communication within plants.

Optical and electrochemical biosensors likewise rely on analog signal conditioning. Transimpedance amplifiers convert femtoamp-level photocurrents from photodiodes into voltages for chlorophyll and fluorescence monitoring [

54,

55], while potentiostatic front-ends capture ion currents in nitrate and potassium sensors [

14,

40]. Finally, hybrid analog impedance–optical circuits enable non-destructive nitrogen estimation, combining modulated LED spectroscopy with phase-sensitive detection to quantify leaf nitrogen and chlorophyll content under ambient light [

56,

57]. Nitrogen measurement is further discussed in the following section.

3.4. Using Optical Sensors for Assessing Crop Nitrogen Nutrition

Nitrogen (N) is one of the most impactful nutrients for crop growth and productivity, as it is an essential constituent of proteins, chlorophyll, nucleotides, and nucleic acids in DNA and RNA [

58]. The early assessment of N deficiency is a key factor that can significantly contribute to proper nitrogen fertilization management, especially considering the low use efficiency of N by crops [

59]. The accurate identification of N deficiency, before the plant exhibits any visible symptoms, allows for the recommendation of appropriate dosages at phenological stages of higher crop demand when properly calibrated. This reduces the potential for losses and increases the efficiency of N fertilization [

60]. The use of portable optical sensors, such as SPAD (Soil-Plant Analysis Development) meters or similar devices [

60], has become increasingly important in this regard, given the promising results obtained across various crops [

61,

62,

63]. These findings have contributed to the growing popularity and widespread adoption of this technology in agriculture [

61,

63].

Regarding the operating principle, SPAD readings, for instance, are calculated based on two light transmission values: the transmission of red light at 650 nm, which is absorbed by chlorophyll, and the transmission of infrared light at 940 nm, at which no chlorophyll absorption occurs [

64]. Since nitrogen is a central component of the chlorophyll molecule, a lower light absorbance indicates a lower chlorophyll content and, consequently, a potential nitrogen deficit in the plant. This enables an early diagnosis prior to the appearance of visual symptoms [

61,

62]. Therefore, while the underlying principle of this technique is relatively straightforward, it requires careful calibration for more widespread and accurate use [

65].

Together, these biosensing approaches illustrate how analog electronics (through impedance measurement, low-noise amplification, and synchronous detection) form the indispensable interface between plant physiology and precision agriculture.

3.5. Power Electronics and Energy Interfaces in Agri-Systems

Power electronics represents another non-digital branch of electronics that is also critical for modern agricultural systems. It functions as the intermediary that converts electrical energy from diverse sources (such as solar, wind, batteries, and the power grid) into precise voltage, current, and frequency levels required by sensors, actuators, and automation units. Unlike digital control circuits that interpret and decide, power converters physically mediate the flow of energy through continuous, modulation of semiconductor switches. This continuous-time regulation is also used to regulate pumps, fans, lighting, thermal systems, and mobile agri-robots, allowing energy-efficient, precise, and responsive operation across widely varying field conditions [

1,

66].

In agricultural contexts, power electronics address three major challenges: energy conversion, energy storage, and distributed actuation. Energy conversion involves DC–DC and DC–AC (or AC-DC) interfaces that connect renewable sources (e.g., photovoltaic modules or small wind turbines) to systems and loads. For instance, DC-DC boost converters and maximum power point tracking (MPPT) circuits ensure efficient solar energy harvesting for irrigation or greenhouse ventilation [

67,

68]. These converters rely on analog sensors to maintain stability under transient irradiance and temperature variations.

Energy storage and regulation depend on bidirectional DC–DC converters interfaced with batteries or supercapacitors, managing charge/discharge cycles through analog sensing of voltage, current, and temperature [

69,

70]. In off-grid or hybrid microgrid farms, such converters are coupled to inverters that synthesize sinusoidal voltages to drive induction or permanent-magnet motors for pumps and conveyors [

71,

72]. The electrification of agricultural machinery further amplifies the role of power electronics. Drones and autonomous ground vehicles now integrate motor drives normally using field-oriented control (FOC), which requires current sensing and rotor position [

73,

74].

Power conditioning also underlies controlled-environment agriculture. LED horticultural lighting systems employ constant-current drivers with analog dimming control to modulate photon flux density according to plant photoperiod requirements [

75,

76]. Temperature and humidity actuators in greenhouses operate through triac-based AC regulators and phase-control circuits that maintain fine-grained thermal stability with minimal electrical losses. Similarly, power-factor correction (PFC) and harmonic filters ensure grid compatibility and reduce electrical noise that could interfere with nearby sensing electronics [

77].

In irrigation and fertigation systems, voltage analog electronics drive solenoid valves and proportional pumps. These actuators rely on analog pulse-width or current-control circuits for proportional response, minimizing water and nutrient waste [

78].

Recent advances in energy-autonomous agricultural systems have emphasized hybrid analog-digital controllers, where analog inner loops manage fast dynamics while digital supervisors optimize overall energy dispatch [

79]. This dual-layer design allows for local analog stability and global adaptive control, essential for farms operating under variable renewable energy inputs and intermittent wireless connectivity.

Ultimately, power electronics enable the sustainable electrification of agriculture by providing the dynamic energy interfaces through which analog and digital systems converge. Every actuation (whether the spin of a drone motor, the dimming of a horticultural LED, or the pulse of an irrigation pump) depends on the power processing made possible by modern power converters.

4. Other Analog Applications – Future Perspectives

Beyond their well-established role in transduction and signal conditioning, analog circuits are expanding into frontiers that integrate physics-based sensing with chemical, biological, and microfluidic domains. Particularly promising directions, i.e., miniaturized nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, as well as microfluidic and electrochemical sensing, highlight the continuing relevance of analog design principles in emerging agricultural and environmental technologies.

Miniaturized NMR and EPR systems have recently benefited from the convergence of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) integration, and low-noise analog front-end circuitry. Traditional benchtop spectrometers rely on bulky superconducting magnets and digital signal processing; however, the latest portable analog architectures employ resonant LC circuits, low-phase-noise oscillators, and transimpedance amplifiers to detect the faint magnetic resonance signals from nuclei or unpaired electron spins. For example, Aiello

et al. demonstrated a low-field NMR platform using analog frequency mixing and phase-sensitive detection that achieved spectral resolution sufficient for chemical identification in small-volume samples, paving the way for in-field soil and plant metabolomics applications [

80]. Similarly, Kazemi

et al. reported a miniaturized EPR spectrometer employing analog lock-in amplification to detect free radicals in agricultural matrices, emphasizing that analog demodulation can outperform digital sampling under low-signal, high-noise conditions typical of open-field environments [

81]. Such systems could enable in situ monitoring of soil organic matter oxidation, nitrogen transformations, or plant stress metabolites without laboratory infrastructure—an essential step toward precision nutrient management and sustainable crop production.

Another rapidly evolving field lies in microfluidic and electrochemical sensing, where analog front-ends are indispensable for maintaining signal fidelity in microscale liquid environments. Recent developments in ion-sensitive field-effect transistor (ISFET) arrays and microfluidic impedance sensors rely heavily on analog readout circuits capable of sub-picoampere current measurement and noise suppression through chopper stabilization and correlated double sampling. Riedel

et al. presented an ISFET-based measurement module for in-field soil nutrient and hydroponic analysis that integrated analog buffering and drift-compensated amplifiers, achieving real-time detection of nitrate and potassium ions with high accuracy under fluctuating environmental conditions [

40]. In another example, Yuan

et al. engineered a CMOS analog interface for a lab-on-chip electrochemical sensor designed to quantify phytohormones in sap flows, emphasizing that precision analog filtering and gain control were critical for maintaining linearity across temperature and ionic strength variations [

82]. The synergy between microfluidics, electrochemistry, and analog signal conditioning offers a foundation for next-generation agricultural analytics systems capable of autonomously assessing soil chemistry, plant physiology, and water quality in distributed field networks.

Together, these emerging domains demonstrate that analog electronics remain not only relevant but indispensable in translating physical and chemical phenomena into actionable agricultural data. As sensor platforms become smaller and more integrated, the analog core (comprising amplifiers, filters, oscillators, and resonators) continues to define the system’s sensitivity, selectivity, and robustness. The future of precision agriculture thus depends on advancing these analog architectures to operate in ultra-low-power regimes, maintain calibration in harsh field conditions, and interface seamlessly with hybrid analog–digital intelligence for adaptive environmental decision-making.

5. Comparison and Overview

Analog electronics in agriculture encompasses a wide spectrum of technologies, from early electroculture experiments and resistive moisture sensors to sophisticated biosensing, energy systems, and microfluidic devices. Despite their diversity, all these systems share a unifying principle: the manipulation of continuously varying electrical quantities that directly correspond to the physical parameters being measured or actuated. This section provides a comparative analysis of the principal analog domains discussed throughout this paper, i.e., namely, soil and water sensing, analog front-ends for chemical and optical detection, biosensing and plant physiology circuits, and power electronics for actuation and energy conversion.

Table 2 summarizes the essential operational characteristics, performance trade-offs, and practical application contexts of these technologies.

From the comparative analysis, it becomes evident that the complexity, precision, and cost of analog systems scale with the degree of physical abstraction they handle. Resistive and capacitive soil probes remain highly affordable and adequate for irrigation management, yet their calibration drift and salinity sensitivity restrict their utility in research-grade monitoring. Conversely, TDR and impedance-based sensors provide metrological accuracy but at the expense of circuit complexity and energy consumption. Analog front-ends for electrochemical and optical measurements deliver a critical bridge between chemical processes and electronic interpretation, allowing in-situ monitoring of ions, pigments, and metabolites, i.e., applications increasingly relevant to nutrient management and crop physiology.

Biosensing and plant electrophysiology circuits occupy an even more delicate analog regime, operating with femtoampere currents and microvolt potentials. Their success depends on low-noise amplification, precise impedance matching, and synchronous detection, i.e., all inherently analog operations that digital systems can only approximate. Similarly, power electronics serve as the analog “muscles” of agricultural automation, transforming energy and controlling actuators through continuous-time modulation of voltage and current waveforms. At the frontier, miniaturized NMR/EPR and microfluidic systems extend analog sensing into molecular and micro-scale domains, where phase coherence, resonance, and electrochemical transduction dominate, requiring ultra-stable analog circuits.

The table below compares these representative analog technologies across criteria such as physical principle, signal domain, typical frequency range, primary application, analog circuitry type, strengths, and limitations. The summary highlights that while digital computation is essential for data storage and analysis, the sensory and actuation backbone of agriculture will remain firmly analog in nature.

The comparison reinforces that analog circuits form the indispensable foundation of every sensing, actuation, and energy conversion process in agriculture. Whether managing soil-water balance, monitoring biochemical pathways, or powering autonomous field robots, these technologies operate in continuous domains where the subtleties of voltage, current, and phase encode the physical reality of life itself. Future agricultural electronics will therefore not replace analog systems but rather deepen their integration with digital intelligence—creating hybrid architectures where analog precision and digital adaptability coexist to sustain the world’s growing need for food, energy, and environmental stewardship.

6. Conclusions

This review has presented analog electronics as the indispensable substrate upon which modern agricultural technologies are built. Long before (and inevitably beneath) digital analytics, analog circuits convert physical and biochemical phenomena into measurable electrical quantities and, in turn, deliver controlled energy back to the farm through precise actuation. From moisture sensing and ion-selective potentiometry to optical readouts, bioimpedance, and emerging NMR/EPR and microfluidic platforms, the evidence surveyed here shows that the fidelity, latency, and energy efficiency demanded by field conditions are fundamentally governed by analog design choices: impedance matching, noise and drift suppression, bandwidth selection, reference stability, and robust front-end architectures. Digital computation undoubtedly scales decisions and connectivity, but it is the continuous-time domain that grants agriculture its perception capability.

References

- Basso, B.; Antle, J. Digital agriculture to design sustainable agricultural systems. Nature Sustainability 2020, 3, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfert, S.; Ge, L.; Verdouw, C.; Bogaardt, M.J. Big Data in Smart Farming – A review. Agricultural Systems 2017, 153, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Jacob, F.; Duveiller, G. Remote sensing for agricultural applications: A meta-review. Remote Sensing of Environment 2020, 236, 111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Singh, A.; Sarkar, S. Deep learning for plant stress phenotyping. Trends in Plant Science 2018, 23, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfouche, A.L.; Nakhle, F.; Harfouche, A.H.; et al. A primer on artificial intelligence in plant digital phenomics. Trends in Plant Science 2023, 28, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.; Finger, R.; Huber, R.; Buchmann, N. Smart farming is key to developing sustainable agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 6148–6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vougioukas, S.G. Agricultural robotics. Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems 2019, 2, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajoie-O’Malley, A.; Bronson, K.; van der Burg, S.; Klerkx, L. The future(s) of digital agriculture and sustainable food futures: A review and research agenda. Global Food Security 2020, 23, 100326. [Google Scholar]

- Finger, R. Digital innovations for sustainable and resilient agricultural systems. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2023, 50, 1277–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Gao, P.; Ding, Y.; Li, X. Review of the Internet-of-Things communication technologies in smart agriculture and challenges. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 189, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, B.; Pasha, S.; Rao, S. S.; Kumar, K. S. IoT based light intensity and temperature monitoring for smart agricultural applications. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 33, 4246–4250. [Google Scholar]

- Mahan, J. R.; Yeater, K. M. Agricultural applications of a low-cost infrared thermometer. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2008, 64, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M., P.; Sarma, U. Analog Frontend for Fringe-Field Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensor. Journal of Basic and Applied Engineering Research 2015, 2, 1698–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.-Y.; Khuntia, S.; Ahn, C. H.; Zhang, B.; Tai, L.-C. Electrochemical Devices to Monitor Ionic Analytes for Healthcare and Industrial Applications. Chemosensors 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscarra Rossel, R. A.; Walter, C. Rapid, quantitative and spatial field measurements of soil pH using an ion sensitive field effect transistor. Geoderma 2004, 119, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, A.; Allam, A.; Abdel-Rahman, A.B.; El-Ansary, D. A novel microwave applicator for sandy soil disinfection. Proceedings of the 2018 Progress in Electromagnetics Research Symposium (PIERS-Toyama), 2018. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos Jr, E. C. Weed Control. Transactions of the ASAE 1973, 16, 773–776. [Google Scholar]

- Phene, C. J.; Hoffman, G. J.; Austin, R. S. Controlling automated irrigation with soil matric potential sensor. Transactions of the ASAE 1973, 16, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Hsu, C.-L.; Jafari, R.; Hall, D. A. A Dynamically Reconfigurable ECG Analog Front-End With a 2.5× Data-Dependent Power Reduction. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems 2021, 15, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petäjäjärvi, J.; Mikhaylov, K.; Vuohtoniemi, R.; Karvonen, H.; Inatti, J. On the Human Body Communications: Wake-Up Receiver Design and Channel Characterization. EURASIP Journal on Wireless Communications and Networking 2016, 2016, Article–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Economic Research Service. Agricultural Productivity in the U.S. Data Product. Data as of January 2024.

- Bertholon de Saint–Lazare, P. De l’électricité des végétaux: Ouvrage dans lequel on traite de l’électricité de l’atmosphère sur les plantes, de ses effets sur l’économie des végétaux, de leurs vertus médico & nutritivo–électriques, & principalement des moyens de pratique de l’appliquer utilement à l’agriculture, avec l’invention d’un électro–végétomètre, Ed.; Bernuset: Paris, France, 1783. [Google Scholar]

- Lemström, S. Electricity in Agriculture and Horticulture; The W. Heinemann: London, UK, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Lodge, O. Experiments on the Electrical Stimulation of Plants. The Electrician 1892, 28, 608–609. [Google Scholar]

- Christianto, V.; Smarandache, F. A Review on Electroculture, Magneticulture and Laserculture to Boost Plant Growth. Bulletin of Pure and Applied Sciences - Botany, 65-69 (2021). :contentReference[oaicite, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chier, M.; Oakey, A.; Budny, M.L.; Lemoine, N.P. Passive electroculture using copper rods does not improve yield in home container vegetable gardening. PLoS ONE, 1: (2025). :contentReference[oaicite, 0329. [Google Scholar]

- G. J. Bouyoucos and A. H. Mick, “An electrical resistance method for measuring the moisture content of soils,” Proc. Soil Sci. Soc. Am., vol. 4, pp. 65–71, 1939.

- C. J. Phene and T. A. Howell, “Soil sensor control of irrigation,” in Proc. 4th Nat. Irrigation Symp., ASAE, 1984, pp. 266–272.

- Topp, G.C.; Davis, J.L.; Annan, A.P. Electromagnetic determination of soil water content: Measurements in coaxial transmission lines. Water Resources Research 1980, 16, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Carlos, G.A.; Jacobina, C.B.; Méllo, J.P.R.A.; dos Santos, E.C. Cascaded Open-End Winding Transformer Based DVR. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2018, 54, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, K.J.; Murray, R.M. Feedback Systems: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers. Princeton University Press 2008. [Google Scholar]

- van Henten, E.J. Greenhouse Climate Management: An Optimal Control Approach; Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen Agricultural University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lieth, J.H.; Burger, D.W. Growth of chrysanthemum using an irrigation system controlled by soil moisture tension. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 1989, 114, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiehl, P.A.; Lieth, J.H.; Burger, D.W. Growth response of chrysanthemum to various container medium moisture tension levels (computer-controlled drip irrigation). Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 1992, 117, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shock, C.C.; Feibert, E.B.G.; Saunders, L.D. Soil water tension: a powerful measurement for productivity and stewardship. HortScience 2011, 46, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamchuk, V.I.; Hummel, J.W.; Morgan, M.T.; Upadhyaya, S.K. On-the-go soil sensors for precision agriculture: an overview of electrical and electrochemical measurement methods. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2004, 44, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, R.E. Ion-selective electrode determinations of exchangeable NH4+ and Ba2+–K+ in soil extracts. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1987, 51, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, O.A.; Bugbee, B. Inherent limitations of nondestructive chlorophyll meters: a comparison of two types of meters. HortScience 1992, 27, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarianakis, Z.; et al. Development of a low-cost chlorophyll meter: exploring analog photometric circuits for plant health monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, Article. [Google Scholar]

- Riedel, V.; Hinck, S.; Peiter, E.; Ruckelshausen, A. Concept and realisation of ISFET-based measurement modules for in-field soil nutrient analysis and hydroponic systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Zhang, M. Design and performance evaluation of an in-situ online soil electrical conductivity sensor prototype based on the high-performance integrated chip AD5941. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enz, C.C.; Temes, G.C. Circuit techniques for reducing the effects of op-amp imperfections: autozeroing, correlated double sampling, and chopper stabilization. Proceedings of the IEEE 1996, 84, 1584–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijsing, J.H. Operational Amplifiers: Theory and Design, 2nd ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pallàs-Areny, R.; Webster, J.G. Sensors and Signal Conditioning, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, R.; Temes, G.C. Understanding Delta–Sigma Data Converters; Wiley-IEEE Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kester, W. (Ed.). The Data Conversion Handbook; Newnes/Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Repo, T.; Korhonen, A.; Lim, C. C.; Sutinen, S. Electrical impedance spectroscopy of Scots pine needles during desiccation and freezing. Trees 2014, 28, 593–603. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ma, C.; Zhao, H.; et al. Frequency-domain bioimpedance for noninvasive plant water status assessment. Biosystems Engineering 2021, 202, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, D. A.; Chacón, A.; Chávez, R.; et al. Electrical impedance spectroscopy for plant water stress monitoring in field conditions. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 240, 106312. [Google Scholar]

- Volkov, A. G. Plant Electrophysiology: Signaling and Responses; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, J.; Lautner, S. Electrical signals and their physiological significance in plants. Plant, Cell & Environment 2019, 42, 611–623. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, M. A.; Furlan, C. M.; et al. Low-noise instrumentation amplifiers for long-term bioelectrical potential measurements in plants. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2018, 67, 2361–2370. [Google Scholar]

- Canales, J.; Gutiérrez, E.; Ochoa, J.; et al. Analog front-end design for electrophysiological signal acquisition in plants. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021, 341, 130015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; He, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Compact analog front-end for real-time chlorophyll fluorescence sensing in field crops. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 21078–21086. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, G.; Marini, D.; Facchi, A.; et al. Analog optical instrumentation for continuous plant photosynthesis monitoring under field conditions. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2023, 331, 109336. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J. A.; Ramírez, F.; Cifuentes, J. Development of an analog spectroscopic sensor for in-field nitrogen estimation in coffee plants. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 174, 105505. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Non-destructive nitrogen estimation in wheat using combined analog impedance and optical sensing techniques. Sensors 2023, 23, 9741. [Google Scholar]

- The, S.V.; Snyder, R.; Tegeder, M. Targeting nitrogen metabolism and transport processes to improve plant nitrogen use efficiency. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 11, 628366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Sanclemente, W.; Perez-Castillo, A.G.; Monge-Muñoz, M.; et al. Impact of urease inhibitor on greenhouse gas emissions and rice yield in a rainfed transplanting rice system in Costa Rica. Frontiers in Agronomy 2025, 7, 1518802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Shaloo; Bisht, H. ; et al. Nitrogen management sensor optimization, yield, economics, and nitrogen use efficiency of different wheat cultivars under varying nitrogen levels. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2023, 7, 1228221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, B.; Singha, P.; Roy Chowdhury, A.; et al. Optical sensor-based nitrogen management: an environmentally friendly and cost-effective approach for sustainable wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) production on Eastern plains of India. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2023, 7, 1153575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Khura, T.K.; Parray, R.A.; et al. The use of destructive and nondestructive techniques in concrete nitrogen assessment in plants. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2024, 47, 2271–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putti, F.F.; Guerrero, P.H.L.; Putti, J.P.B.; et al. Estimation of lettuce shoot nitrogen via a portable spectrophotometer. Discover Agriculture 2025, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddling, J.; Gelang-Alfredsson, J.; Piikki, K.; Pleijel, H. Evaluating the relationship between leaf chlorophyll concentration and SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter readings. Photosynthesis Research 2007, 91, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; et al. SPAD-based leaf nitrogen estimation is impacted by environmental factors and crop leaf characteristics. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 13389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, M. A.; Zahawi, B.; Atkinson, D. J. Analysis and design of analog MPPT controllers for photovoltaic systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2019, 34, 1235–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Esram, T.; Chapman, P. L. Comparison of photovoltaic array maximum power point tracking techniques. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2007, 22, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Abido, M. A. Hybrid analog–digital MPPT control for solar-powered irrigation systems. Renewable Energy 2023, 205, 484–496. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, D. Design of bidirectional DC–DC converter for energy storage in agricultural microgrids. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 212093–212104. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Choi, B. H. High-efficiency bidirectional converter for standalone PV-based irrigation systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2016, 63, 988–996. [Google Scholar]

- Meshram, P. M.; Borghate, V. B. A review on analog and digital control of DC–DC converters. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2017, 32, 7789–7805. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, A. C.; Gallo, C. A.; dos Santos, E. C. Jr. Modular inverter architectures for photovoltaic-based agricultural drives. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2019, 55, 5213–5223. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. J.; Eberle, W.; Rahman, K. M. Energy-efficient motor drives for agricultural electrification. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2021, 57, 2338–2349. [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez, J.; Guerrero, J. M. Analog-digital hybrid control for field-oriented agricultural motor drives. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2020, 67, 10145–10155. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, P.; Halonen, L. Analog dimming strategies for LED horticultural lighting systems. Lighting Research and Technology 2013, 45, 407–420. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. D.; Ibaraki, Y. Light quality and power electronics in controlled environment agriculture. Environmental Control in Biology 2017, 55, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Al-Haddad, K.; Chandra, A. A review of active filters for power quality improvement. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2003, 46, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, F.; Porras, A.; et al. Power electronics-based proportional control of irrigation valves for water-saving agriculture. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 149, 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, J.; Luo, F. Analog–digital hybrid control of renewable energy systems in precision agriculture. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 150, 111520. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, G.; Finocchio, E.; Alabiso, G.; et al. Portable low-field NMR spectrometer for chemical analysis using analog frequency mixing. Sensors 2023, 23, 7012. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, P.; Kashi, M.; Shafiee, A.; et al. Miniaturized EPR spectrometer with analog lock-in detection for low-field radical analysis. Review of Scientific Instruments 2022, 93, 064705. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; et al. CMOS analog interface for lab-on-chip electrochemical detection of phytohormones in plant sap. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 12458–12467. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).