Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Nomenclature

| temperature rise | |

| density of crude oil | |

| density (bulk) of crude oil reservoir | |

| AHU | air handling unit |

| AL | artificial lift |

| AOR | assisted oil recovery |

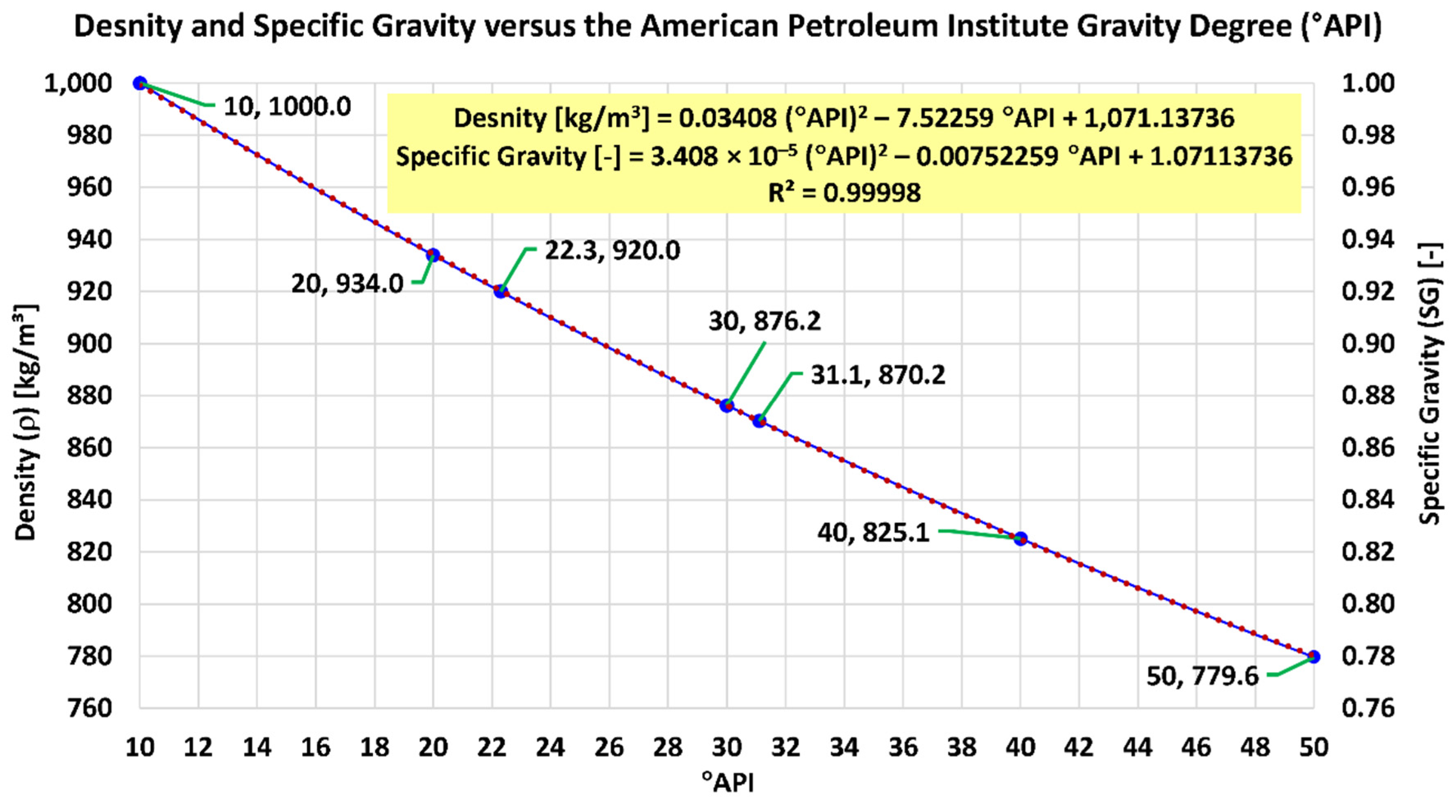

| °API | American Petroleum Institute gravity degree |

| Bcf | billion standard cubic feet of natural gas (approximately equivalent to 1,000,000 MMBtu lower heating value “LHV”) |

| CaCO3 | calcium carbonate |

| CF | capacity factor |

| representative specific heat capacity of a crude oil reservoir | |

| DNI | direct normal irradiance |

| EOR | enhanced oil recovery (same as tertiary oil recovery, TOR) |

| ESEOR | enclosed solar enhanced oil recovery |

| GCR | ground coverage ratio |

| GHG | greenhouse gas |

| GWh | gigawatt-hour (equivalent to 3.6 TJ or 3.6 × 106 MJ) |

| HAPP | hydraulically activated pipeline pigging |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| reference length of a reservoir zone to be heated | |

| LFR | linear Fresnel reflectors |

| LHV | lower heating value |

| MJ | megajoule (106 J) |

| MMBtu | million British thermal unit (equivalent to 1,055.1 MJ or 10 therms) [1,2] |

| MNm3 | million normal cubic meters of natural gas (approximately 35,000 MMBtu or 36,930 GJ lower heating value “LHV”) 3 |

| MWth | megawatt of thermal power |

| number of moles | |

| NG | natural gas |

| NL | normal liter |

| Nm3 | normal cubic meter of natural gas (approximately 35,000 Btu or 36,930 kJ lower heating value “LHV”) |

| OIIP | oil-initially-in-place |

| OOIP | original oil-in-place |

| OTSG | once-through steam generator [4,5,6] |

| absolute pressure | |

| PDC | parabolic dish collector |

| PDO | Petroleum Development Oman |

| PJ | petajoule (quadrillion joules, 1015 J or 1,000 TJ) |

| ppb | part per billion |

| ppm | part per million |

| PTC | parabolic trough collector |

| heat needed to increase the temperature of a reservoir zone | |

| universal (molar) gas constant, 8.3145 J/mol.K [7] | |

| SCC | stress corrosion cracking |

| SEOR | solar enhanced oil recovery |

| specific gravity | |

| SHIP | solar heat for industrial processes |

| SOR | steam-oil ratio |

| absolute temperature | |

| TDS | total dissolved solids |

| TEOR | thermal enhanced oil recovery |

| TES | total energy supply |

| TFC | total final consumption of energy |

| therm | 105 Btu (equivalent to 0.1 MMBtu) [8,9] |

| TJ | terajoule (1012 J) |

| volume |

2. Introduction

2.1. Importance of Sustainability for Oman

2.2. Enclosed Solar Enhanced Oil Recovery (ESEOR)

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Objectives and Contributions

- Providing an example (a case study) of sustainable business operation in the oil industry. The current study is considered unique in terms of the provided independent technical and performance analysis of successful and flagship projects of enclosed solar enhanced oil recovery (ESEOR).

- Contrasting the three enclosed solar enhanced oil recovery (ESEOR) project designs in Oman, to derive best practices.

- Validating public data against first-principles models in a simple and reproducible way. Such validated data include avoided emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2).

- Discussing general aspects and challenges of solar enhanced oil recovery (SEOR).

3.2. Approach and Data Sources

- (1)

- The GlassPoint website.

- (2)

- Research publications by GlassPoint staff.

- (3)

- Personal communications with GlassPoint staff, through which further proprietary information was obtained.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. The Choice of Parabolic Trough Collectors

- Maturity: Parabolic trough collectors are a very reliable technology that has been proven to be successful for many years, including large commercial-scale plants operating with stable conditions and low technological risks. A good example is the Mojave Solar project is a 250-megawatt solar electric generating facility (280 MW gross) in California, USA [158,159]. This commercial-scale PTC power plant has been operational for more than a decade (commissioned at the beginning of December 2014) [160].

- Modularity: Parabolic trough collectors are very scalable. They can be installed under a wide range of thermal capacities, ranging from a few kilowatts to hundreds of megawatts [161]. This makes them attractive for a diverse spectrum of industrial applications, including solar enhanced oil recovery.

- Simple construction: Parabolic trough collectors can be viewed as composed primarily of repetitive components (mirrors and receiver tube) and common materials (steel and glass) [162]. No large construction is needed (as in the case of the solar towers or the linear Fresnel reflectors). Also, the one-dimensional solar tracking in the case of parabolic trough collectors [163] tends to be easier to maintain and install than the two-dimensional (two-angles) solar tracking in the case of parabolic dish collectors or the heliostats of a solar tower.

- Low cost: The structural simplicity and the maturity of parabolic trough collectors make them one of the lowest-cost solar options [164].

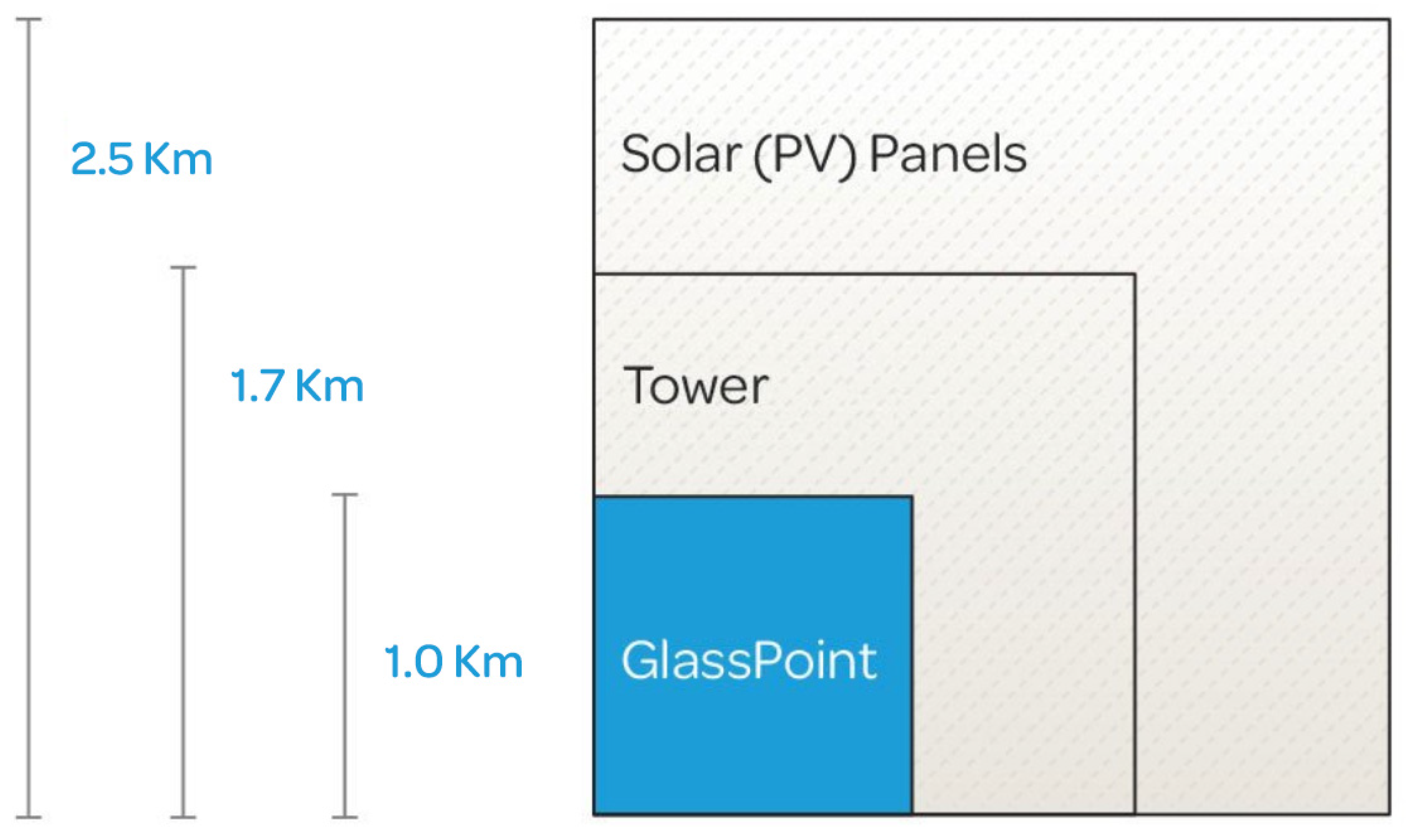

- Effective land use: Compared to linear Fresnel reflectors (LFR) and solar towers, parabolic trough collectors (PTC) can permit better utilization of the available land area for the same power capacity.

4.2. Contrasting the Three Enclosed Solar EOR Projects

4.3. Thermal and Emissions Validation Model

4.4. Illustrative Sketches

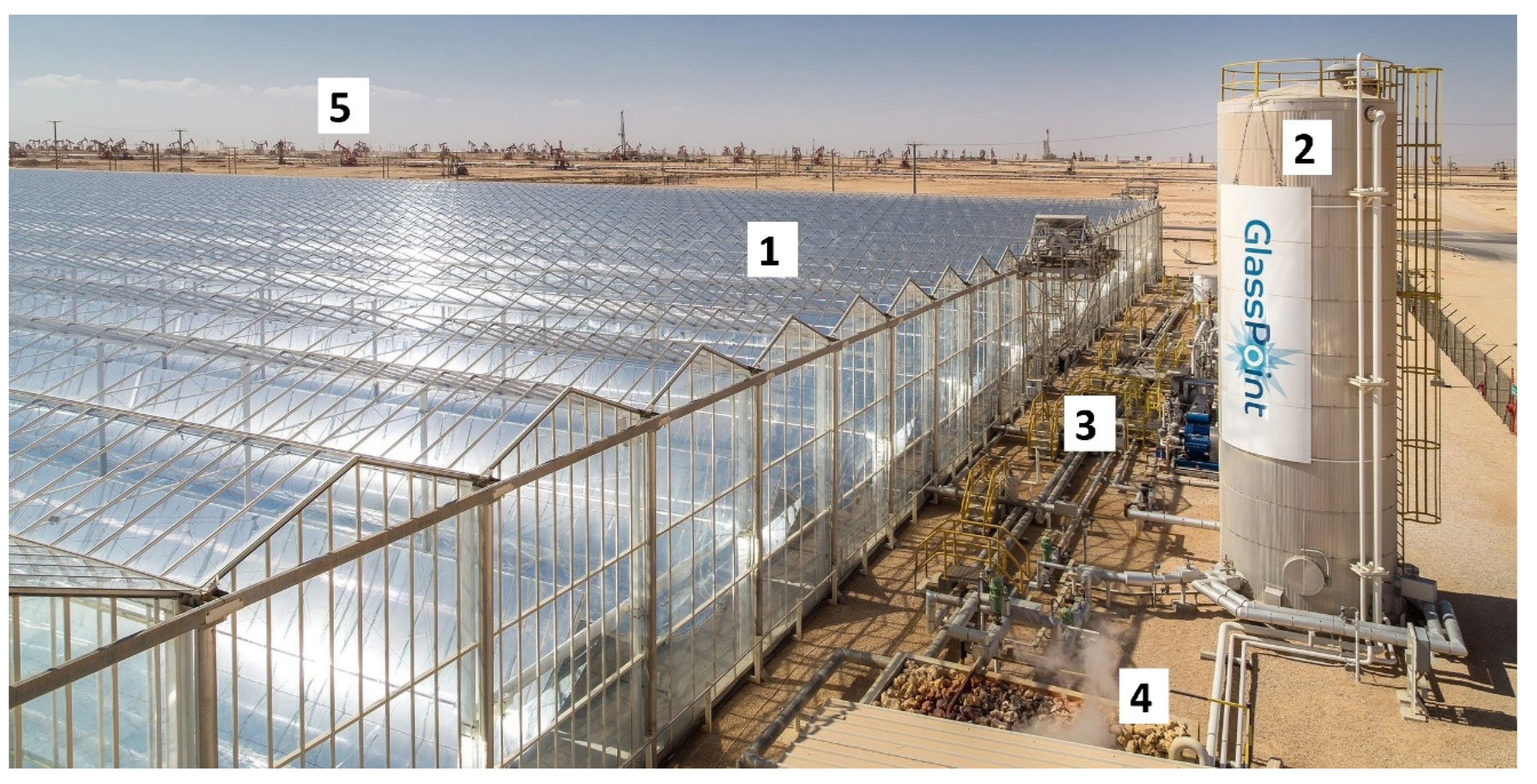

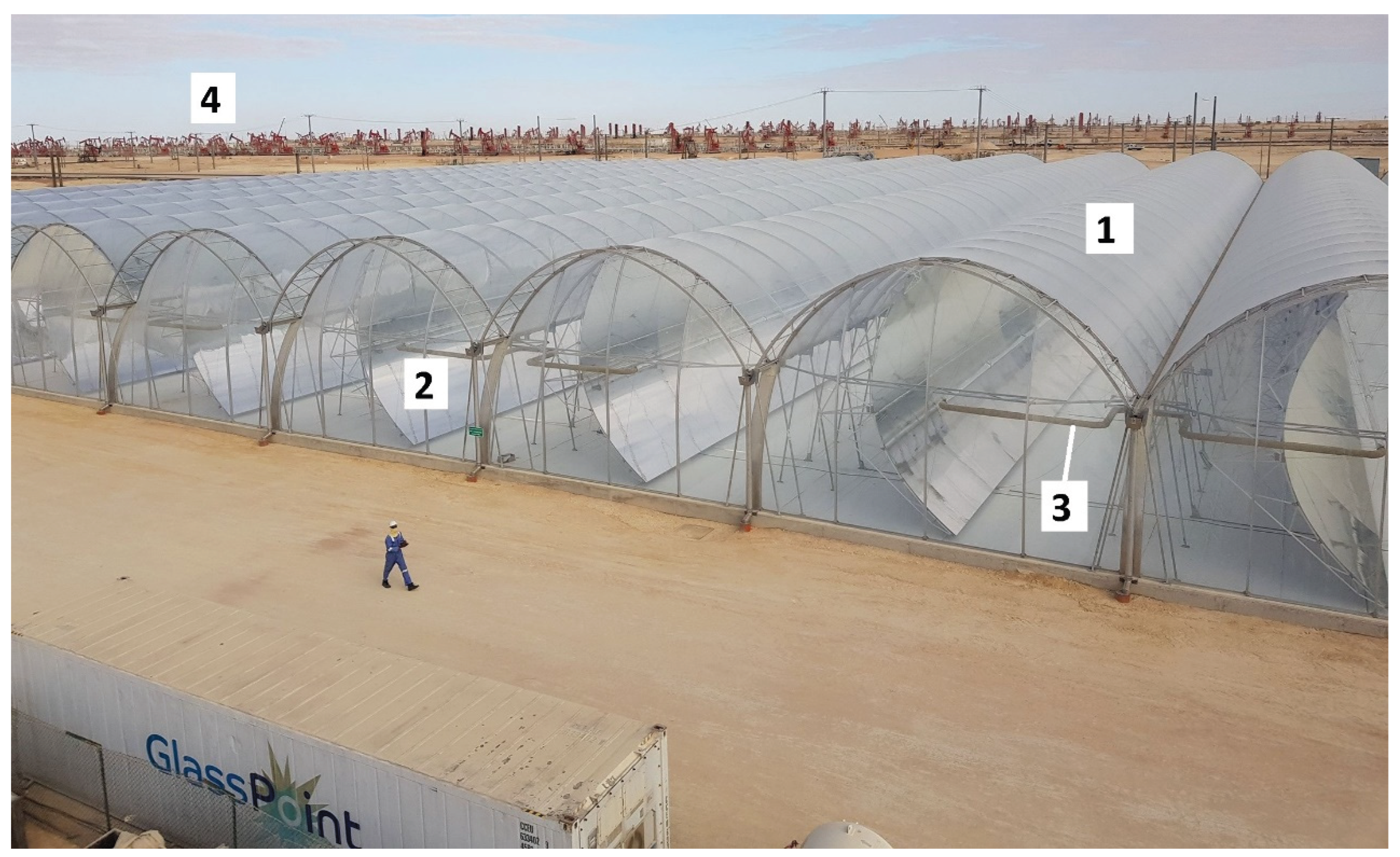

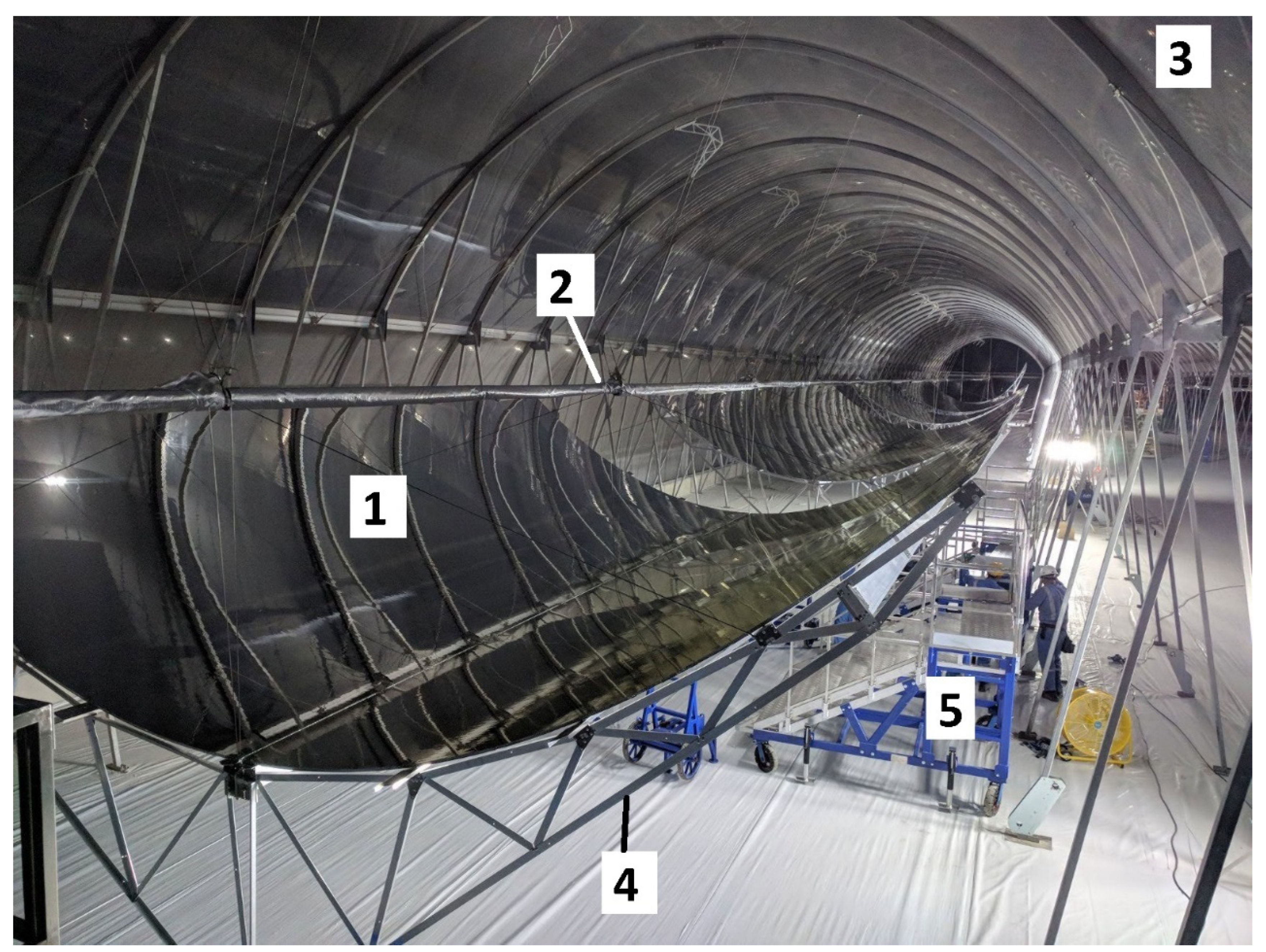

4.5. Selected Photos

4.6. Challenges

4.7. Steam-Oil Ratio (SOR)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Declaration of Competing Interests Statement

References

- Williams, A. E. Industrial Energy Systems Handbook, 1st ed.; River Publishers: New York, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, G.; Moretti, S.; Conti, A. Units and Conversion Factors. In Fin Shape Thermal Optimization Using Bejan’s Constructal Theory; Synthesis Lectures on Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2011; pp 41–46. [CrossRef]

- NewMed Energy. NewMed Energy │ Energy Calculator. https://newmedenergy.com/energy-calculator/ (accessed 2025-08-02).

- Fanaritis, J. P.; Warren, Pa.; Kimmel, J. D. Review of Once-Through Steam Generators. J Pet Technol 1965, 17 (04), 409–416. [CrossRef]

- Tzanos, C. P. A Movable Boundary Model for Once-Through Steam Generator Analysis. Nuclear Technology 1988, 82 (1), 5–17. [CrossRef]

- YOON, J.; KIM, J.-P.; KIM, H.-Y.; LEE, D. J.; CHANG, M. H. Development of a Computer Code, ONCESG, for the Thermal-Hydraulic Design of a Once-Through Steam Generator. Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology 2000, 37 (5), 445–454. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. O.; Williams, W. C.; McFarlane, J.; Kropaczek, D.; de Wet, D. Semi-Empirical Model for Henry’s Law Constant of Noble Gases in Molten Salts. Sci Rep 2024, 14 (1), 12847. [CrossRef]

- Brown, N. L. Renewable Energy Resources And Rural Applications In The Developing World, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- EIA, [United States Energy Information Administration]. EIA │Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) = What are Ccf, Mcf, Btu, and therms? https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=45&t=8 (accessed 2025-08-02).

- Khaledi, C. K. A.; Khosravi, M.; Tavousi, T.; Hamidianpour, M.; Moghadam, M. K. Future Warming of the Gulf of Oman: SST Trends under Contrasting Climate Scenarios by 2050. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2024, 77, 103682. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. CCKP │ Climate Change Knowledge Portal - Oman (Historical Trends). https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/oman/trends-variability-historical (accessed 2025-06-07).

- Dreyfus, G. B.; Xu, Y.; Shindell, D. T.; Zaelke, D.; Ramanathan, V. Mitigating Climate Disruption in Time: A Self-Consistent Approach for Avoiding Both near-Term and Long-Term Global Warming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119 (22), e2123536119. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Simulation of a Swirling Gas-Particle Flow Using Different k-Epsilon Models and Particle-Parcel Relationships. Engineering Letters 2010, 18 (1).

- Pall, P.; Allen, M. R.; Stone, D. A. Testing the Clausius–Clapeyron Constraint on Changes in Extreme Precipitation under CO2 Warming. Clim Dyn 2007, 28 (4), 351–363. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T. J.; Farukh, Murad. A.; Fukushima, T.; Inatsu, M.; Sato, T.; Pokhrel, Y. N.; Oki, T. Extreme Precipitation Intensity in Future Climates Associated with the Clausius-Clapeyron-like Relationship. Hydrological Research Letters 2014, 8 (4), 108–113. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A. M.; Hennessy, K. J. Potential Impacts of Global Warming on the Frequency and Magnitude of Heavy Precipitation. Nat Hazards 1995, 11 (3), 283–303. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Xie, S.-P.; Hu, K.; Huang, G.; Huang, R. Patterns of the Seasonal Response of Tropical Rainfall to Global Warming. Nature Geosci 2013, 6 (5), 357–361. [CrossRef]

- Radwan, N.; Halder, B.; Ahmed, M. F.; Refadah, S. S.; Khan, M. Y. A.; Scholz, M.; Sammen, S. S.; Pande, C. B. Seasonal Precipitation and Anomaly Analysis in Middle East Asian Countries Using Google Earth Engine. Water 2025, 17 (10), 1475. [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.; Fonseca, R.; Nelli, N.; Cherif, C.; Yarragunta, Y.; Zittis, G.; Jan de Vries, A. From Cause to Consequence: Examining the Historic April 2024 Rainstorm in the United Arab Emirates through the Lens of Climate Change. npj Clim Atmos Sci 2025, 8 (1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- GDACS, [Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System]. Overall Green Alert Flood in Oman (GDACS ID: FL 1102566). https://www.gdacs.org/report.aspx?eventtype=FL&eventid=1102566 (accessed 2025-05-25).

- Marzouk, O. A. Assessment of Global Warming in Al Buraimi, Sultanate of Oman Based on Statistical Analysis of NASA POWER Data over 39 Years, and Testing the Reliability of NASA POWER against Meteorological Measurements. Heliyon 2021, 7 (3), e06625. [CrossRef]

- Bruhwiler, L.; Basu, S.; Butler, J. H.; Chatterjee, A.; Dlugokencky, E.; Kenney, M. A.; McComiskey, A.; Montzka, S. A.; Stanitski, D. Observations of Greenhouse Gases as Climate Indicators. Climatic Change 2021, 165 (1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Temperature-Dependent Functions of the Electron–Neutral Momentum Transfer Collision Cross Sections of Selected Combustion Plasma Species. Applied Sciences 2023, 13 (20), 11282. [CrossRef]

- Szulejko, J. E.; Kumar, P.; Deep, A.; Kim, K.-H. Global Warming Projections to 2100 Using Simple CO2 Greenhouse Gas Modeling and Comments on CO2 Climate Sensitivity Factor. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2017, 8 (1), 136–140. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Combined Oxy-Fuel Magnetohydrodynamic Power Cycle. In Conference on Energy Challenges in Oman (ECO’2015); DU [Dhofar University]: Salalah, Dhofar, Oman, 2015.

- Lindholt, L.; Glomsrød, S. Phasing out Coal and Phasing in Renewables – Good or Bad News for Arctic Gas Producers? Energy Economics 2018, 70, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Shindell, D.; Smith, C. J. Climate and Air-Quality Benefits of a Realistic Phase-out of Fossil Fuels. Nature 2019, 573 (7774), 408–411. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Recommended LEED-Compliant Cars, SUVs, Vans, Pickup Trucks, Station Wagons, and Two Seaters for Smart Cities Based on the Environmental Damage Index (EDX) and Green Score. In Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 7; Ben Ahmed, M., Boudhir, A. A., El Meouche, R., Karaș, İ. R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Vol. 906, pp 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Nadimuthu, L. P. R.; Victor, K. Socio-Techno-Economic-Environmental Analysis of Vehicle-to-Grid-Integrated E-Mobility in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: A Case Study. In Handbook on New Paradigms in Smart Charging for E-Mobility; Kumar, A., Bansal, R. C., Kumar, P., He, X., Eds.; Elsevier, 2025; pp 447–480. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Urban Air Mobility and Flying Cars: Overview, Examples, Prospects, Drawbacks, and Solutions. Open Engineering 2022, 12 (1), 662–679. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Dai, L.; Ali, S.; Nazar, R.; Anser, M. K. Zero-Emission Vision: The Role of E-Mobility Technology Budgets in Carbon Mitigation. Transport Policy 2025, 164, 265–280. [CrossRef]

- Vavouris, A.; Guasselli, F.; Stankovic, L.; Stankovic, V.; Gram-Hanssen, K.; Didierjean, S. A Complex Mixed-Methods Data-Driven Energy-Centric Evaluation of Net-Positive Households. Applied Energy 2024, 367, 123404. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, W.; Luo, W.; Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y. Application of Hybrid Machine Learning Algorithm in Multi-Objective Optimization of Green Building Energy Efficiency. Energy 2025, 316, 133581. [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, E. M.; Okonkwo, P. C.; Ben Belgacem, I.; Zghaibeh, M.; Tlili, I. Optimal Sizing of Photovoltaic Systems Based Green Hydrogen Refueling Stations Case Study Oman. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47 (75), 31964–31973. [CrossRef]

- Elkelawy, M.; Draz, A. M.; Antar, A. M.; Seleem, H. E. Enhancing Diesel Generator Efficiency and Emissions with CNG and Green Hydrogen: A Sustainable Solution for Power Plants. Pharos Engineering Science Journal 2025. [CrossRef]

- Squadrito, G.; Maggio, G.; Nicita, A. The Green Hydrogen Revolution. Renewable Energy 2023, 216, 119041. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Levelized Cost of Green Hydrogen (LCOH) in the Sultanate of Oman Using H2A-Lite with Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) Electrolyzers Powered by Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Electricity. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 469, 00101. [CrossRef]

- Mio, A.; Barbera, E.; Massi Pavan, A.; Bertucco, A.; Fermeglia, M. Sustainability Analysis of Hydrogen Production Processes. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 54, 540–553. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.; Treyer, K.; Antonini, C.; Bergerson, J.; Gazzani, M.; Gencer, E.; Gibbins, J.; Mazzotti, M.; T. McCoy, S.; McKenna, R.; Pietzcker, R.; P. Ravikumar, A.; C. Romano, M.; Ueckerdt, F.; Vente, J.; Spek, M. van der. On the Climate Impacts of Blue Hydrogen Production. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2022, 6 (1), 66–75. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Detailed and Simplified Plasma Models in Combined-Cycle Magnetohydrodynamic Power Systems. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 2023, 10 (11), 96–108. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. High-Efficiency Power Generation – Review of Alternative Systems; IEA Clean Coal Centr: London, UK, 2015; pp 1–120. https://usea.org/sites/default/files/032015_High-efficiency%20power%20generation%20-%20review%20of%20alternative%20systems_ccc247.pdf (accessed 2025-05-26).

- Marzouk, O. A. Detailed Derivation of the Scalar Explicit Expressions Governing the Electric Field, Current Density, and Volumetric Power Density in the Four Types of Linear Divergent MHD Channels Under a Unidirectional Applied Magnetic Field. Contemporary Mathematics 2025, 6 (4), 4060–4100. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. New Weighted Sum of Gray Gases (WSGG) Models for Radiation Calculation in Carbon Capture Simulations: Evaluation and Different Implementation Techniques. In 7th U.S. National Technical Meeting of the Combustion Institute; Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2011; Vol. 4, pp 2483–2496.

- Marzouk, O. A. Reduced-Order Modeling (ROM) of a Segmented Plug-Flow Reactor (PFR) for Hydrogen Separation in Integrated Gasification Combined Cycles (IGCC). Processes 2025, 13 (5), 1455. [CrossRef]

- IEA, [International Energy Agency]. IEA │ World Energy Statistics and Balances. IEA. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/world-energy-statistics-and-balances (accessed 2025-07-31).

- GEM, [Global Energy Monitor]. Dhofar II Wind Farm - Global Energy Monitor Profile. https://www.gem.wiki/Dhofar_II_wind_farm (accessed 2024-08-08).

- MEM, [Minister of Energy and Minerals in the Sultanate of Oman]. MEM │ Dhofar wind farm. https://mem.gov.om/en-us/Our-Business/Renewable-Energy-and-Hydrogen/Renewable-Energy-and-Hydrogen-Projects/ArtMID/732/ArticleID/1325/Dhofar-wind-farm (accessed 2024-10-28).

- Masdar. Dhofar Wind Power Project; Public Announcement; 2022. https://masdar.ae/-/media/corporate/projects/downloads/dhofar-wind-power/dhofar-wind-power-project_eng.pdf (accessed 2023-10-30).

- Marzouk, O. A. OpenFOAM Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Solver for Magnetohydrodynamic Open Cycles, Applied to the Sakhalin Pulsed Magnetohydrodynamic Generator (PMHDG). Discover Applied Sciences 2025, 7 (10), 1108. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Changes in Fluctuation Waves in Coherent Airflow Structures with Input Perturbation. WSEAS Transactions on Signal Processing 2008, 4 (10), 604–614.

- York, R. How Much Can We Expect the Rise in U.S. Domestic Energy Production to Suppress Net Energy Imports? Social Currents 2015. [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, T.; Bórawski, P.; Szeberényi, A. The Impact of the 2020–2022 Crises on EU Countries’ Independence from Energy Imports, Particularly from Russia. Energies 2023, 16 (18), 6629. [CrossRef]

- Yufenyuy, M.; Addai, K.; Kirikkaleli, D. Assessing the Effect of Transport Infrastructure Investments and Total Energy Supply on Material Footprint: Insights from France. Energy & Environment 2025, 0958305X251326183. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Assessment of Syngas Kinetic Models for the Prediction of a Turbulent Nonpremixed Flame. In Fall Meeting of the Eastern States Section of the Combustion Institute; College Park, Maryland, USA, 2009; pp 726–751.

- Kazem, H. A. Renewable Energy in Oman: Status and Future Prospects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15 (8), 3465–3469. [CrossRef]

- GEM, [Global Energy Monitor]. GEM │ Ibri 2 Solar - Profile. https://www.gem.wiki/Ibri_2_Solar (accessed 2024-08-07).

- MEM, [Sultanate of Oman Minister of Energy and Minerals]. MEM │ Ibri 2 Solar IPP. https://mem.gov.om/en-us/Our-Business/Renewable-Energy-and-Hydrogen/Renewable-Energy-and-Hydrogen-Projects/ArtMID/732/ArticleID/1324/Ibri-2-Solar-IPP (accessed 2025-06-09).

- MEM, [Ministry of Energy and Minerals in the Sultanate of Oman]. MEM │ The Sultanate of Oman’s National Strategy for an Orderly Transition to Net Zero; MEM [Ministry of Energy and Minerals in the Sultanate of Oman]]: Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2022; pp 1–42. https://www.ea.gov.om/media/xdvpdu1w/oman-net-zero-report-2022_screen.pdf (accessed 2024-05-13).

- Marzouk, O. A. University Role in Promoting Leadership and Commitment to the Community. In Inaugural International Forum on World Universities; Davos, Switzerland, 2008.

- Al. Shibli, S. ICAO │ Oman Vision 2040: A National Blueprint for Sustainable Environment and Clean Energy. In ICAO 2025 Environmental Report - Skyward Action - Realizing Aviation’s Sustainable Future; ICAO [International Civil Aviation Organization]: Montreal, Canada, 2025; pp 257–259.

- Marzouk, O. A. Benchmarking Retention, Progression, and Graduation Rates in Undergraduate Higher Education Across Different Time Windows. Cogent Education 2025, 12 (1), 2498170. [CrossRef]

- OAAAQA, [Oman Authority for Academic Accreditation and Quality Assurance of Education]. Institutional Standards Assessment Manual (ISAM) - Institutional Accreditation: Stage 2, Version 1; Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2016. https://oaaaqa.gov.om/getattachment/c63fde93-150b-430d-a58f-9f68e6dc2390/Institutional%20Standards%20Assessment%20Manual.aspx (accessed 2024-10-08).

- Marzouk, O. A. English Programs for Non-English Speaking College Students. In 1st Knowledge Globalization Conference 2008 (KGLOBAL 2008); Sawyer Business School, Suffolk University: Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 2008; pp 1–8.

- OAAAQA, [Oman Authority for Academic Accreditation and Quality Assurance of Education]. Programme Standards Assessment Manual (PSAM) - Programme Accreditation, Version 1; Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2023. https://oaaaqa.gov.om/getattachment/4359b83e-5ab9-4147-8e73-1ff0f9adcfae/Programme%20Standards%20Assessment%20Manual.aspx (accessed 2024-10-08).

- Marzouk, O. A. Benchmarking the Trends of Urbanization in the Gulf Cooperation Council: Outlook to 2050. In 1st National Symposium on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Management (NSETEM’2017); WCAS [Waljat College of Applied Sciences], Muscat, Oman, 2017; pp 1–9.

- Om2040U, [Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit]. Oman Vision 2040 │ Follow-up System. https://www.oman2040.om/organization?lang=en (accessed 2024-07-30).

- Om2040U, [Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit]. Oman 2040 Vision Document; Om2040U [Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit]: Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2020. https://www.oman2040.om/VisionDocument?lang=en (accessed 2023-10-06).

- Om2040U, [Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit]. Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit Website A Platform Promoting Transparency, Participation and Direct Communication. https://www.oman2040.om/news/6?lang=en (accessed 2025-06-29).

- Denney, D. EOR Potential in the Middle East: Current and Future Trends. J Pet Technol 2012, 64 (01), 70–73. [CrossRef]

- Oxford Analytica. Oman Will Innovate to Meet Growing Energy Needs. Expert Briefings 2017. [CrossRef]

- Nellist, M. D. Integration of Solar Steam Facilities with Existing Steam Generation Systems; OnePetro, 2018. [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, R. Q&A with Rod MacGregor, Chief Executive Officer and President, GlassPoint Solar. J Pet Technol 2013, 65 (10), 62–63. [CrossRef]

- Shell. Shell │ Petroleum Development Oman (PDO). https://www.shell.com.om/about-us/what-we-do/qalhat-lng-saoc.html (accessed 2025-06-28).

- PDO, [Petroleum Development Oman]. PDO │ A Shining Beacon: Miraah Solar Project. https://www.pdo.co.om/en/Pages/Sustainability/EnvironmentalProjects.aspx?proID=3 (accessed 2025-08-02).

- PDO, [Petroleum Development Oman]. PDO │ EcOman Centre. https://www.pdo.co.om/knowledgeworld/Pages/ecoman.aspx (accessed 2025-08-02).

- .

- Sammy, T. D.; Ehirim, E. O.; Ugi, F. B. Modeling the Effect of Temperature for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) Using Steam Injection Technique. Journal of Newviews in Engineering and Technology 2023, 5 (1), 22–31.

- Lee, K. S. The Effects of Temperature-Dependent Fluids’ Viscosity on the Performance of a Polymer Flood in Reservoir Systems with an Elevated Temperature. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2011, 33 (18), 1706–1714. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. S. Nonisothermal Assessment on the Performance of Polymer Flood in the Reservoir with Elevated Temperature; OnePetro, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Askarova, A.; Turakhanov, A.; Markovic, S.; Popov, E.; Maksakov, K.; Usachev, G.; Karpov, V.; Cheremisin, A. Thermal Enhanced Oil Recovery in Deep Heavy Oil Carbonates: Experimental and Numerical Study on a Hot Water Injection Performance. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 194, 107456. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. J. Chapter 2 - Rock Physical and Mechanical Properties. In Applied Petroleum Geomechanics; Zhang, J. J., Ed.; Gulf Professional Publishing, 2019; pp 29–83. [CrossRef]

- Beyer, L. A.; Clutsom, F. G. USGS │ Density and Porosity of Oil Reservoirs and Overlying Formations from Borehole Gravity Measurements, Gebo Oil Field, Hot Springs County, Wyoming; USGS [United States Geological Survey], United States Department of the Interior: Reston, Virginia, USA, 1978; pp 1–24. https://pubs.usgs.gov/oc/088/report.pdf (accessed 2025-08-02).

- Sun, J.; Wang, B.; Shu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Tian, C. The Numerical Simulation Study on the Heat Transfer Mechanism in Heavy Oil Reservoirs During In-Situ Combustion. Processes 2025, 13 (1), 56. [CrossRef]

- Sumeru, K.; Pramudantoro, T. P.; Setyawan, A. Experimental Investigation on the Performance of Residential Air Conditioning System Using Water Condensate for Subcooling. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 197, 08002. [CrossRef]

- Tamainot-Telto, Z.; Metcalf, S. J.; Yande, N. N. Adsorption Solar Air Conditioning System for Singapore Climate. Energies 2022, 15 (18), 6537. [CrossRef]

- Kuma, Y.; Ozaki, A. Development of Central Air Conditioning Circulation System for Condominium Unit and Evaluation of the Indoor Environment in Summer. In Advances in Computer Science and Ubiquitous Computing; Park, J. S., Yang, L. T., Pan, Y., Park, J. J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Negara, I. G. A.; Temaja, I. W.; Midiani, L. P. I.; Santosa, I. D. M. C.; Wirajati, I. G. A. B.; Arsana, M. E. Experimental Analysis of Thermodynamic Performance for 2.5 kW Split Inverter Air Conditioning Unit with R-410A. International Journal of Automotive and Mechanical Engineering 2025, 22 (2), 12388–12403. [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. A.; Cheah, L. Uncertainty Quantification in Life Cycle Assessments: Interindividual Variability and Sensitivity Analysis in LCA of Air-Conditioning Systems. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2017, 21 (5), 1103–1114. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Prakash, O.; Kausher, R.; Kumar, G.; Pandey, S.; Hasnain, S. M. M. Parabolic Trough Solar Collectors: A Sustainable and Efficient Energy Source. Materials Science for Energy Technologies 2024, 7, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Bees Group. Solar Heat for Industrial Process - SHIP. https://www.beesgroup.energy/en/services/solar-heat-for-industrial-process-ship (accessed 2025-04-20).

- EPA, [United States Environmental Protection Agency]. Solar Heating and Cooling Technologies. https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/rhc/solar-heating-and-cooling-technologies (accessed 2025-04-19).

- Marzouk, O. A.; Al Kamzari, A. A.; Al-Hatmi, T. K.; Al Alawi, O. S.; Al-Zadjali, H. A.; Al Haseed, M. A.; Al Daqaq, K. H.; Al-Aliyani, A. R.; Al-Aliyani, A. N.; Al Balushi, A. A.; Al Shamsi, M. H. Energy Analyses for a Steam Power Plant Operating under the Rankine Cycle. In First International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences and Management (UoB-IEASMA 2021); Al Kalbani, A. S., Kanna, R., EP Rabai, L. B., Ahmad, S., Valsala, S., Eds.; IEASMA Consultants LLP: Virtual, 2021; pp 11–22.

- Perez Cordoba, J. H.; Gonzalez Sanchez, E. D.; Martinez Vertel, J. J.; Muñoz Navarro, S. F. Surface Facilities Development for Steam Flue Gas Injection in a Colombian Heavy Oil Reservoir; OnePetro, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J. R.; Naranjo, P. A. L.; Molina, J. W.; Molina, J. D.; Molina, F.; Matute, A. K. Unveiling Success From Cyclic Steam Injections for Heavy Oil Recovery in India and the Orinoco Oil Belt; OnePetro, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Jul, W. A. M. H. R.; Al Jabri, A. M. K.; Al-ghaithi, H. A. M. A. Construction of a Small-Scale Vacuum Generation System and Using It as an Educational Device to Demonstrate Features of the Vacuum. International Journal of Contemporary Education 2018, 1 (2), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.-F. Empirical Correlations of Saturated Steam Properties. SPE Res Eng 1992, 7 (02), 295–303. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. A Two-Step Computational Aeroacoustics Method Applied to High-Speed Flows. Noise Control Engineering Journal 2008, 56 (5), 396. [CrossRef]

- Egerton, A. C.; Callendar, G. S. On the Saturation Pressures of Steam (170° to 374° C.). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical or Physical Character 1997, 231 (694–706), 147–205. [CrossRef]

- Struchtrup, H. Thermodynamics and Energy Conversion, 1st ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2014.

- ASME, [American Society of Mechanical Engineers]. ASME Steam Tables, Compact Edition; ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers]: New York City, New York, USA, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Verma, M. P. Steam Tables for Pure Water as an ActiveX Component in Visual Basic 6.0. Computers & Geosciences 2003, 29 (9), 1155–1163. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Thermo Physical Chemical Properties of Fluids Using the Free NIST Chemistry WebBook Database. Fluid Mechanics Research International Journal 2017, 1 (1). [CrossRef]

- Babita; Pant, U.; Meena, H.; Gupta, G.; Bapna, K.; Shivagan, D. D. Improved Realization of Ensemble of Triple Point of Water Cells at CSIR-NPL. MAPAN 2021, 36 (3), 615–628. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meijer, H. A. J. Ice–Liquid Isotope Fractionation Factors for 18O and 2H Deduced from the Isotopic Correction Constants for the Triple Point of Water. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies 2018, 54 (3), 304–311. [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, D. The New Hot Ticket [Concentrating Solar Thermal Power]. Engineering & Technology 2009, 4 (15), 48–51. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. A Flight-Mechanics Solver for Aircraft Inverse Simulations and Application to 3D Mirage-III Maneuver. Global Journal of Control Engineering and Technology 2015, 1, 14–26.

- Núnez Bootello, J. P.; Mier-Torrecilla, M.; Doblaré, M.; Silva Pérez, M. Aerodynamics of New Solar Parametric Troughs: Two Dimensional and Three Dimensional Single Module Numerical Analysis. Solar Energy 2016, 135, 742–749. [CrossRef]

- Roschke, E. J. Wind Loading on Solar Concentrators: Some General Considerations; Contractor Report (CR) JPL-PUB-83-101; JPL [Jet Propulsion Laboratory]: Pasadena, California, USA, 1984; pp 1–174. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19840024844/downloads/19840024844.pdf (accessed 2025-08-02).

- Marzouk, O. A. Contrasting the Cartesian and Polar Forms of the Shedding-Induced Force Vector in Response to 12 Subharmonic and Superharmonic Mechanical Excitations. Fluid Dynamics Research 2010, 42 (3), 035507. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, E. C.; Chilingarian, G. V.; Yen, T. F. Enhanced Oil Recovery, I: Fundamentals and Analyses; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985.

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/s/steam-assisted_gravity_drainage (accessed 2025-10-31).

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Steamflood. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/s/steamflood (accessed 2025-10-31).

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Huff and Puff. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/h/huff_and_puff (accessed 2025-10-31).

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Cyclic Steam Injection. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/c/cyclic_steam_injection (accessed 2025-10-31).

- Johns, R. T. Oil Recovery. In Encyclopedia of Energy; Cleveland, C. J., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, 2004; pp 701–713. [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.; Vij, R. K.; Shah, S. Impact of Newly Implemented Enhanced Oil and Gas Recovery Screening Policy on Current Oil Production and Future Energy Supply in India. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2021, 207, 109196. [CrossRef]

- DOE, [United States Department of Energy]. DOE │ Enhanced Oil Recovery. https://www.energy.gov/fecm/enhanced-oil-recovery (accessed 2025-10-31).

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Miscible Displacement. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/m/miscible_displacement (accessed 2025-10-31).

- Kalita, P.; Sharma, V.; Pandey, L.; Tiwari, P. Secondary and Tertiary Oil Recovery Processes. In Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery: Principles and Potential; Pandey, L., Tiwari, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp 23–50. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, D.; Qin, J.; Lei, Z.; Tian, Y. Novel Approach to Enhancing Tight Oil Recovery Using N2-Assisted CO2 Flooding and Its Potential for CO2 Storage. Energy Fuels 2023, 37 (11), 7667–7678. [CrossRef]

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Secondary Recovery. https://glossary.slb.com/terms/s/secondary_recovery (accessed 2025-10-31).

- Mohan, K.; Gupta, R.; Mohanty, K. K. Wettability Altering Secondary Oil Recovery in Carbonate Rocks. Energy Fuels 2011, 25 (9), 3966–3973. [CrossRef]

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Primary Recovery. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/p/primary_recovery (accessed 2025-10-31).

- Solaimany-Nazar, A. R.; Zonnouri, A. Modeling of Asphaltene Deposition in Oil Reservoirs during Primary Oil Recovery. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2011, 75 (3), 251–259. [CrossRef]

- Hoy, M.; Derler, M.; Lobianco, L.; Knauhs, P.; Marschall, C. Artificial Lift Failures and Operational Challenges in a Chemical EOR Field - A Comparative Analysis of Sucker Rod Pumps and Electric Submersible Pumps; OnePetro, 2024. [CrossRef]

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Artificial Lift. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/a/artificial_lift (accessed 2025-10-31).

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Gas Lift. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/g/gas_lift (accessed 2025-10-31).

- Mokheimer, E. M. A.; Hamdy, M.; Abubakar, Z.; Shakeel, M. R.; Habib, M. A.; Mahmoud, M. A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Enhanced Oil Recovery: Techniques Evaluation. Journal of Energy Resources Technology 2018, 141 (030801). [CrossRef]

- Parshall, J. Challenges, Opportunities Abound for Artificial Lift. J Pet Technol 2013, 65 (03), 70–75. [CrossRef]

- Bucaram, S. M. Managing Artificial Lift. J Pet Technol 1994, 46 (04), 335–340. [CrossRef]

- von Flatern, R. Artificial Lift. Oilfield Review 2015, 27 (2), 1–2.

- Mahdi, M. A. A.; Amish, M.; Oluyemi, G. An Artificial Lift Selection Approach Using Machine Learning: A Case Study in Sudan. Energies 2023, 16 (6), 2853. [CrossRef]

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Injection Well. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/i/injection_well (accessed 2025-10-31).

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Gas Cap. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/g/gas_cap (accessed 2025-10-31).

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Gas Injection. https://glossary.slb.com/en/terms/g/gas_injection (accessed 2025-10-31).

- Khan, W. A.; Rui, Z.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, Y. Application of Machine Learning and Optimization of Oil Recovery and CO2 Sequestration in the Tight Oil Reservoir. SPE J. 2024, 29 (06), 2772–2792. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Xu, F.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Kang, C.; Lu, C.; Li, S.; Bai, L.; Du, S. A New Method of Predicting the Saturation Pressure of Oil Reservoir and Its Application. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45 (55), 30244–30253. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. D.; Ambastha, A.; Ayirala, S.; Bai, B.; Carreras, P.; Hampton, D.; Mohanty, K.; Rossen, W.; Schoeling, L.; Yousef, A. IOR and EOR Terminology Clarifications and Recommendations for the SPE Community; Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M.; Sagandykova, D.; Mukhtarov, A.; Dauyltayeva, A.; Maratbekkyzy, L.; Pourafshary, P.; Musharova, D. Maximizing Oil Recovery: Innovative Chemical EOR Solutions for Residual Oil Mobilization in Kazakhstan’s Waterflooded Sandstone Oilfield. Heliyon 2024, 10 (7). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. Enhanced Oil Recovery - An Overview. Oil & Gas Science and Technology - Rev. IFP 2008, 63 (1), 9–19. [CrossRef]

- Tirado, A.; Félix, G.; Trejo, F.; Varfolomeev, M. A.; Yuan, C.; Nurgaliev, D. K.; Sámano, V.; Ancheyta, J. Properties of Heavy and Extra-Heavy Crude Oils. In Catalytic In-Situ Upgrading of Heavy and Extra-Heavy Crude Oils; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2023; pp 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Huc, A.-Y. Heavy Crude Oils: From Geology to Upgrading : An Overview; Editions TECHNIP, 2011.

- El Bassoussi, A. A.; El-sabagh, S. M.; Harb, F. M.; El Nady, M. M. Characterization and Correlation of Crude Oils from Some Wells in the North Western Desert, Egypt. Petroleum Science and Technology 2018, 36 (5), 384–391. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, S.; Ta, S.; Ray, A. K.; Lakshminarayanan, S. Determination of Density and Viscosity of Crude Oil Samples from FTIR Data Using Multivariate Regression, Variable Selection and Classification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55 (7), 845–850. [CrossRef]

- Correa Pabón, R. E.; Souza Filho, C. R. de. Crude Oil Spectral Signatures and Empirical Models to Derive API Gravity. Fuel 2019, 237, 1119–1131. [CrossRef]

- Lammoglia, T.; Filho, C. R. de S. SATELLITE DETERMINATION OF API GRAVITY AND SARA COMPONENTS OF OFFSHORE PETROLEUM SEEPS. Brazilian Journal of Geophysics 2012, 30 (4), 419–430. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J. Y.; Mullins, O. C.; Freed, D.; Zhang, D. A Simple Relation between Solubility Parameters and Densities for Live Reservoir Fluids. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2010, 55 (9), 2964–2969. [CrossRef]

- Farkha, S. A.; Zangana, M. H. S.; Shoham, O. Evaluation of Compositional Models and PVT Correlations for Iraqi Light Crude Oils Properties. Energy Science & Engineering 2023, 11 (7), 2654–2667. [CrossRef]

- Poirier, L.; Nelson, J.; Leong, D.; Berhane, L.; Hajdu, P.; Lopez-Linares, F. Application of ICP-MS and ICP-OES on the Determination of Nickel, Vanadium, Iron, and Calcium in Petroleum Crude Oils via Direct Dilution. Energy Fuels 2016, 30 (5), 3783–3790. [CrossRef]

- Solar Thermal Conversion Technologies for Industrial Process Heating, 1st ed.; Arjunan, T. V., Selvaraj, V., Matheswaran, M. M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- GlassPoint. GlassPoint projects. https://www.glasspoint.com/projects (accessed 2025-05-24).

- GlassPoint. GlassPoint technology. https://www.glasspoint.com/technology (accessed 2025-05-24).

- SHC, [Solar Heating and Cooling Programme]. Solar Heat for Industrial Processes (SHIP); Technology Position Paper; IEA [International Energy Agency]: Paris, France, 2024; pp 1–9. https://www.iea-shc.org/Data/Sites/1/publications/IEA-SHC-Task64-Technology-Position-Paper-SHIP-2024-01.pdf (accessed 2025-04-18).

- Kalogirou, S. A. Solar Thermal Collectors and Applications. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2004, 30 (3), 231–295. [CrossRef]

- Barone, G.; Buonomano, A.; Forzano, C.; Palombo, A. Chapter 6 - Solar Thermal Collectors. In Solar Hydrogen Production; Calise, F., D’Accadia, M. D., Santarelli, M., Lanzini, A., Ferrero, D., Eds.; Academic Press, 2019; pp 151–178. [CrossRef]

- Goswami, D. Y. Principles of Solar Engineering, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M. Solar Thermal Systems and Applications: New Design Techniques for Improved Thermal Performance; Elsevier: London, UK, 2024.

- ASI, [Atlantica Sustainable Infrastructure ltd.]. ASI │ Powering the energy transition - Mojave. https://atlantica.com/business/assets/asset/mojave/ (accessed 2025-11-01).

- CEC, [California Energy. CEC │ Mojave Solar Project (Abengoa). https://www.energy.ca.gov/powerplant/solar-thermal/mojave-solar-project-abengoa (accessed 2025-11-01).

- Gallego, A. J.; Macías, M.; de Castilla, F.; Camacho, E. F. Mathematical Modeling of the Mojave Solar Plants. Energies 2019, 12 (21), 4197. [CrossRef]

- Tagle-Salazar, P. D.; Nigam, K. D. P.; Rivera-Solorio, C. I. Parabolic Trough Solar Collectors: A General Overview of Technology, Industrial Applications, Energy Market, Modeling, and Standards. Green Processing and Synthesis 2020, 9 (1), 595–649. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-García, A.; Zarza, E.; Valenzuela, L.; Pérez, M. Parabolic-Trough Solar Collectors and Their Applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2010, 14 (7), 1695–1721. [CrossRef]

- Paetzold, J.; Cochard, S.; Fletcher, D. F.; Vassallo, A. Wind Engineering Analysis of Parabolic Trough Collectors to Optimise Wind Loads and Heat Loss. Energy Procedia 2015, 69, 168–177. [CrossRef]

- NREL, [United States National Renewable Energy Laboratory]. NREL │ Parabolic Trough Solar Thermal Electric Power Plants; NREL [United States National Renewable Energy Laboratory], 2006. https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy06osti/40211.pdf (accessed 2025-11-01).

- Mishra, S. Solar Square │ Parabolic Trough Collector: Working, Benefits, And Drawbacks. Rooftop Solar for your home and more - Blog | SolarSquare. https://solarsquare.in/blog/parabolic-trough-collector/ (accessed 2025-11-01).

- Natraj; Rao, B. N.; Reddy, K. S. Wind Load and Structural Analysis for Standalone Solar Parabolic Trough Collector. Renewable Energy 2021, 173, 688–703. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Simulation, Analysis, and Explanation of the Lift Suppression and Break of 2:1 Force Coupling Due to in-Line Structural Vibration. In 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Schaumburg, Illinois, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-2309. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Directivity and Noise Propagation for Supersonic Free Jets. In 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-23. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Accurate Prediction of Noise Generation and Propagation. In 18th Engineering Mechanics Division Conference of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE-EMD); Zenodo: Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, 2007; pp 1–6.

- Marzouk, O. A. Solar Heat for Industrial Processes (SHIP): An Overview of Its Categories and a Review of Its Recent Progress. Solar 2025, 5 (4), 46. [CrossRef]

- GlassPoint. GlassPoint │ Maaden Solar I. https://www.glasspoint.com/projects/maaden-solar (accessed 2025-08-11).

- Kar, M. K.; Ӧnal, M. A. R.; Borra, C. R. Alumina Recovery from Bauxite Residue: A Concise Review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2023, 198, 107158. [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, A. M.; Frisch, N.; Olney, D. Bauxite Mining and Alumina Refining: Process Description and Occupational Health Risks. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2014, 56, S12. [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, S. A.; Gulhane, N. P. Optical Evaluation of Compound Parabolic Collector with Low Acceptance Angle. Optik 2017, 149, 359–371. [CrossRef]

- Schizas, C. N.; Kalogirou, S.; Neocleous, C. A Comparative Study of Methods for Estimating Intercept Factor of Parabolic Trough Collectors. In Engineering Applications of Neural Networks Conference; London, UK, 1996.

- Christian, J. M.; Ho, C. K. Finite Element Modeling and Ray Tracing of Parabolic Trough Collectors for Evaluation of Optical Intercept Factors With Gravity Loading; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2012; pp 577–585. [CrossRef]

- Kosić, T.; Svetel, I. Technological and Economical Analysis of Curved Glass Structure. Structural Integrity and Life 2022, 22 (2), 175–181.

- Louter, C.; Bos, F.; Belis, J.; Lebet, J.-P. Challenging Glass 4 & COST Action TU0905 Final Conference; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2014.

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Lei, D. Vacuum Reliability Analysis of Parabolic Trough Receiver. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2012, 105, 302–308. [CrossRef]

- Pourbafrani, M.; Ghadamian, H.; Aminy, M.; Moghadasi, M.; Mardani, M.; Akrami, M.; Khaki, A. H.; Sadr, S. M. K. Improving the Energy Performance of an Evacuated Tube Solar Collector Water Heater Using Compound Parabolic Concentrator: An Experimental Study. Journal of Renewable Energy and Environment 2024, 11 (2), 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Bierman, B.; Treynor, C.; O’Donnell, J.; Lawrence, M.; Chandra, M.; Farver, A.; Von Behrens, P.; Lindsay, W. Performance of an Enclosed Trough EOR System in South Oman. Energy Procedia 2014, 49, 1269–1278. [CrossRef]

- GlassPoint. Amal I project in Oman. https://www.glasspoint.com/projects/amal (accessed 2025-05-24).

- Wilson, A. Pilot Steam Generator Uses Solar Energy Successfully for EOR Operations in Oman. J Pet Technol 2015, 67 (06), 111–113. [CrossRef]

- GlassPoint. Amal II project in Oman. https://www.glasspoint.com/projects/amal2 (accessed 2025-05-24).

- Bierman, B.; Al-Lawatia, H.; DiFilippo, M.; O’Donnell, J. Deploying Enclosed Trough for Thermal EOR at Commercial Scale. AIP Conference Proceedings 2018, 2033 (1), 030002. [CrossRef]

- GlassPoint. Miraah project in Oman. https://www.glasspoint.com/projects/miraah (accessed 2025-05-24).

- Madaeni, S. H.; Sioshansi, R.; Denholm, P. Estimating the Capacity Value of Concentrating Solar Power Plants With Thermal Energy Storage: A Case Study of the Southwestern United States. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2013, 28 (2), 1205–1215. [CrossRef]

- Falahati, B.; Kargarian, A.; Fu, Y. Timeframe Capacity Factor Reliability Model for Isolated Microgrids with Renewable Energy Resources. In 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting; 2012; pp 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kamnapure, N. R.; Reddy, K. S. Optical Analysis of Solar Parabolic Trough Collector with Flat Concentrating Photovoltaic Receiver. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2014, 592–594, 2396–2403. [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, F.; Horta, P. IEA SHC │ Comparison of Process Heat Collectors with Respect to Technical and Economic Conditions; Technical Report A.2.1; IEA SHC [International Energy Agency - Solar Heating and Cooling Programme]: Paris, France, 2016; pp 1–36. https://w.iea-shc.org/Data/Sites/1/publications/Task%2049%20Deliverable%20A2%201_End%20(3).pdf (accessed 2025-08-02).

- Quaschning, V.; Kistner, R.; Ortmanns, W. Influence of Direct Normal Irradiance Variation on the Optimal Parabolic Trough Field Size: A Problem Solved with Technical and Economical Simulations. J. Sol. Energy Eng 2002, 124 (2), 160–164. [CrossRef]

- Blanc, P.; Espinar, B.; Geuder, N.; Gueymard, C.; Meyer, R.; Pitz-Paal, R.; Reinhardt, B.; Renné, D.; Sengupta, M.; Wald, L.; Wilbert, S. Direct Normal Irradiance Related Definitions and Applications: The Circumsolar Issue. Solar Energy 2014, 110, 561–577. [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, O.; Lingfors, D. Oversizing Co-Locatedwind and Solar Parks to Increase the Capacity Factor. In 21st Wind & Solar Integration Workshop (WIW 2022); 2022; Vol. 2022, pp 546–552. [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, W.; Grossmann, I.; Steininger, K. W. Solar Electricity Supply Isolines of Generation Capacity and Storage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112 (12), 3663–3668. [CrossRef]

- Strickland, J. Space Solar vs Base Load Ground Solar and Wind Power. Online Journal of Space Communication 2021, 9 (16).

- Marzouk, O. A. Validating a Model for Bluff-Body Burners Using the HM1 Turbulent Nonpremixed Flame. Journal of Advanced Thermal Science Research 2016, 3 (1), 12–23. [CrossRef]

- Innovation Norway. Innovation Norway │ Conversion Guidelines - Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Innovation Norway: Oslo, Norway, 2019; pp 1–3. https://www.eeagrants.gov.pt/media/2776/conversion-guidelines.pdf (accessed 2025-08-25).

- Kvenvolden, K. A. A Review of the Geochemistry of Methane in Natural Gas Hydrate. Organic Geochemistry 1995, 23 (11), 997–1008. [CrossRef]

- Didmanidze, O. N.; Afanasev, A. S.; Hakimov, R. T. Natural Gas Methane Number and Its Influence on the Gas Engine Working Process Efficiency. Записки Гoрнoгo института 2021, 251 (eng), 730–737.

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. A Comparative Study of Eight Finite-Rate Chemistry Kinetics for CO/H2 Combustion. Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics 2010, 4 (3), 331–356. [CrossRef]

- Maia, J. L.; da Silva Neves, M. V. Method of Equivalent CO2 Emissions Sources Identification and Quantification of Offshore Petroleum Production Units; OnePetro, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Carroll, J. J. Carbon Dioxide Thermodynamic Properties Handbook: Covering Temperatures from -20 Degrees to 250 Degrees Celcius and Pressures up to 1000 Bar; John Wiley & Sons: Salem, Massachusetts, USA, 2011.

- NRG Energy. NRG Energy │ Energy conversion calculator. NRG Energy. https://www.nrg.com/resources/energy-tools/energy-conversion-calculator.html (accessed 2025-08-02).

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. Modeling Confined Jets with Particles and Swril. In Machine Learning and Systems Engineering; Ao, S.-I., Rieger, B., Amouzegar, M. A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2010; Vol. 68, pp 243–256. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. InvSim Algorithm for Pre-Computing Airplane Flight Controls in Limited-Range Autonomous Missions, and Demonstration via Double-Roll Maneuver of Mirage III Fighters. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 23382. [CrossRef]

- de Obeso, J. C.; Awolayo, A. N.; Nightingale, M. J.; Tan, C.; Tutolo, B. M. Experimental Study on Plagioclase Dissolution Rates at Conditions Relevant to Mineral Carbonation of Seafloor Basalts. Chemical Geology 2023, 620, 121348. [CrossRef]

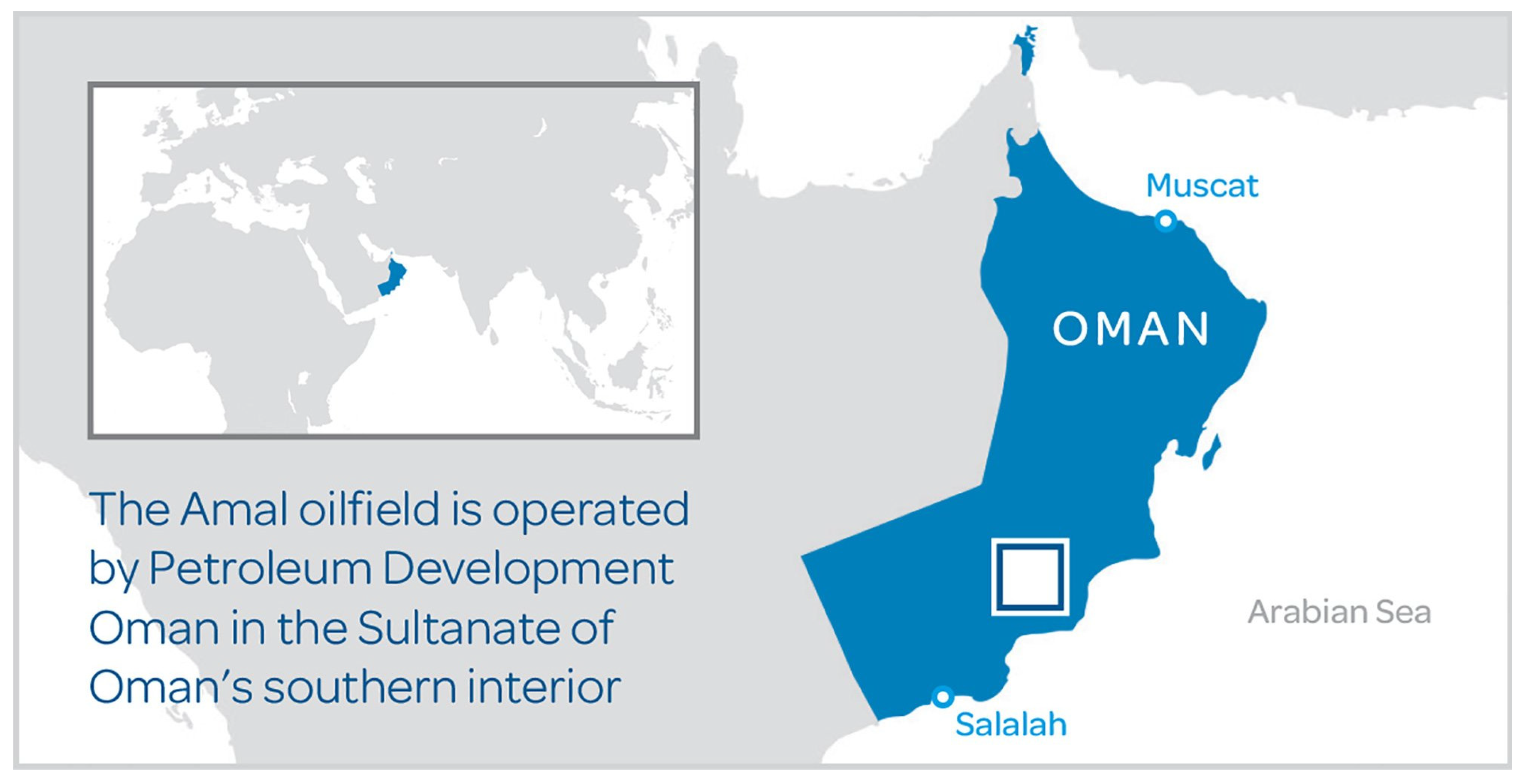

- GlassPoint. Map of the Amal Oil Field in Oman. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/59876962-14d9-4f99-9a6d-b0ada0043a4b/miraah_map.jpg (accessed 2025-05-22).

- Google. Google Maps │ Amal Oil Field. Google Maps. https://maps.app.goo.gl/WRdqNukjoiUs4RFt6 (accessed 2025-08-02).

- OSMF, [OpenStreetMap Foundation]. OpenStreetMap │ Miraah Solar Farm. OpenStreetMap. https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/18.349281/55.684590 (accessed 2025-08-02).

- OSMF, [OpenStreetMap Foundation]. OpenStreetMap │ Copyright and License - Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL). OpenStreetMap. https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright (accessed 2025-07-31).

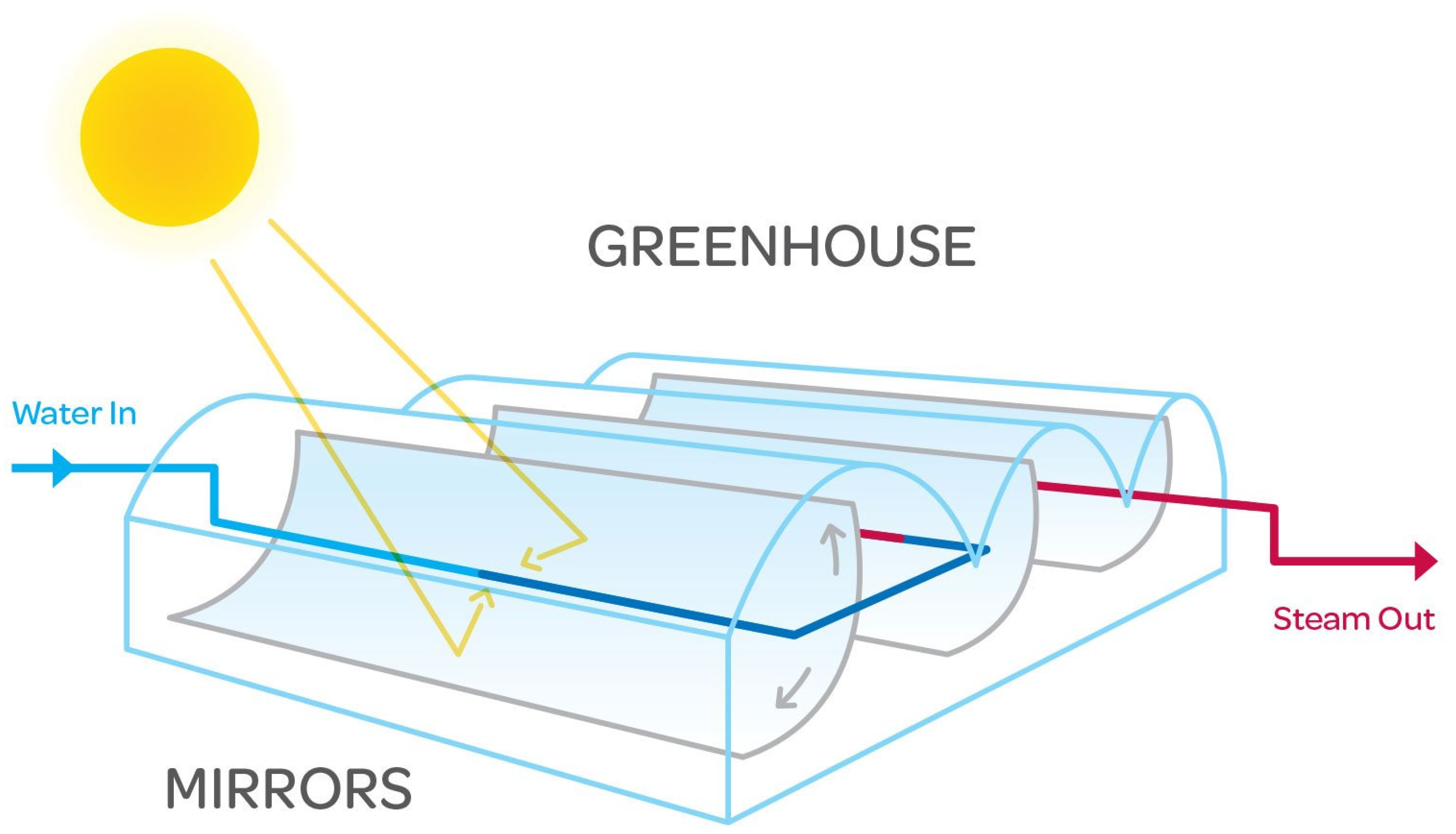

- GlassPoint. Sketch of looped enclosed parabolic troughs. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/c13e3a89-4a12-460b-bfaa-da0a71f3284a/tech1.jpg (accessed 2025-05-24).

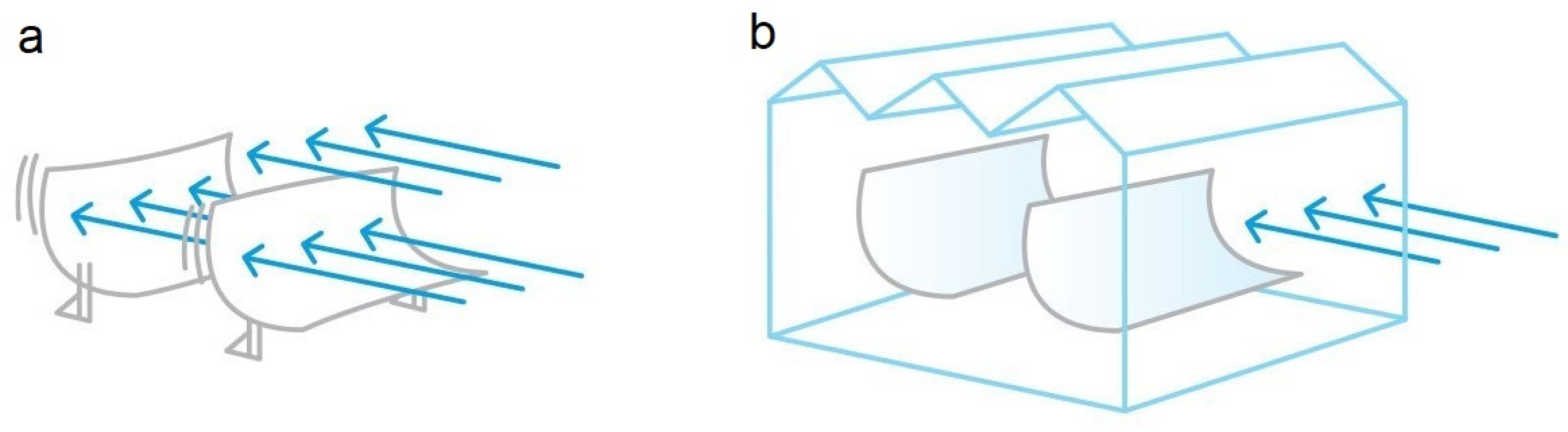

- GlassPoint. Sketch illustrating the structural advantage (wind protection) of enclosed troughs compared to open troughs. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/e732593b-4f97-4cfd-8c3d-877227f7a193/wind.jpg (accessed 2025-05-24).

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Wei, J. J. Multiphysics-Coupled Study of Wind Load Effects on Optical Performance of Parabolic Trough Collector. Solar Energy 2020, 207, 1078–1087. [CrossRef]

- Natraj; Rao, B. N.; Reddy, K. S. Wind Load and Structural Analysis for Standalone Solar Parabolic Trough Collector. Renewable Energy 2021, 173, 688–703. [CrossRef]

- GlassPoint. Comparison of area needs for PV solar system solar tower system or open trough, and enclosed parabolic troughs. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/225ab3da-e05a-488b-901f-b90f65a1a5ac/glasspoint-scale-graphic-revised.png (accessed 2025-05-24).

- Das, P.; V.p., C. A Review on Recent Advances in Hybrid Solar Updraft Tower Plants: Challenges and Future Aspects. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 55, 102978. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, Y. Solar Updraft Tower Power Generation. Solar Energy 2016, 128, 95–125. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Suolang, B.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Y. Novel Approach to Remote Rural Heating: Direct Coupled Photovoltaic Electric Heater Underfloor Heating System with Phase Change Materials. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 250, 123525. [CrossRef]

- GlassPoint. Photo of the Amal I project in Oman. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/1647980305001-LC69P8W8OWNV4OCSF1AD/project2.jpg (accessed 2025-05-24).

- GlassPoint. Photo of the Amal I greenhouse in Oman. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/a5903cf7-be4d-41f6-95fa-441bc534c460/GlassPoint-PDO-13.jpg (accessed 2025-05-24).

- PVsyst. PVsyst │ GCR - Ground coverage Ratio. https://www.pvsyst.com/help-pvsyst7/gcr.htm (accessed 2025-08-02).

- Jensen, A. R.; Sifnaios, I. Modeling, Validation, and Analysis of a Concentrating Solar Collector Field Integrated with a District Heating Network. Solar 2022, 2 (2), 234–250. [CrossRef]

- GlassPoint. Photo of the Amal II greenhouse in Oman. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/1647980963994-D2FX6CA6KIDJHJ7EL260/Advance_RD.jpg (accessed 2025-05-24).

- GlassPoint. Photo of the night installation at the Amal II project in Oman. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/a3f25ef3-1760-47fd-b34f-6b2d63716b3b/Advance_RD2.jpg (accessed 2025-05-24).

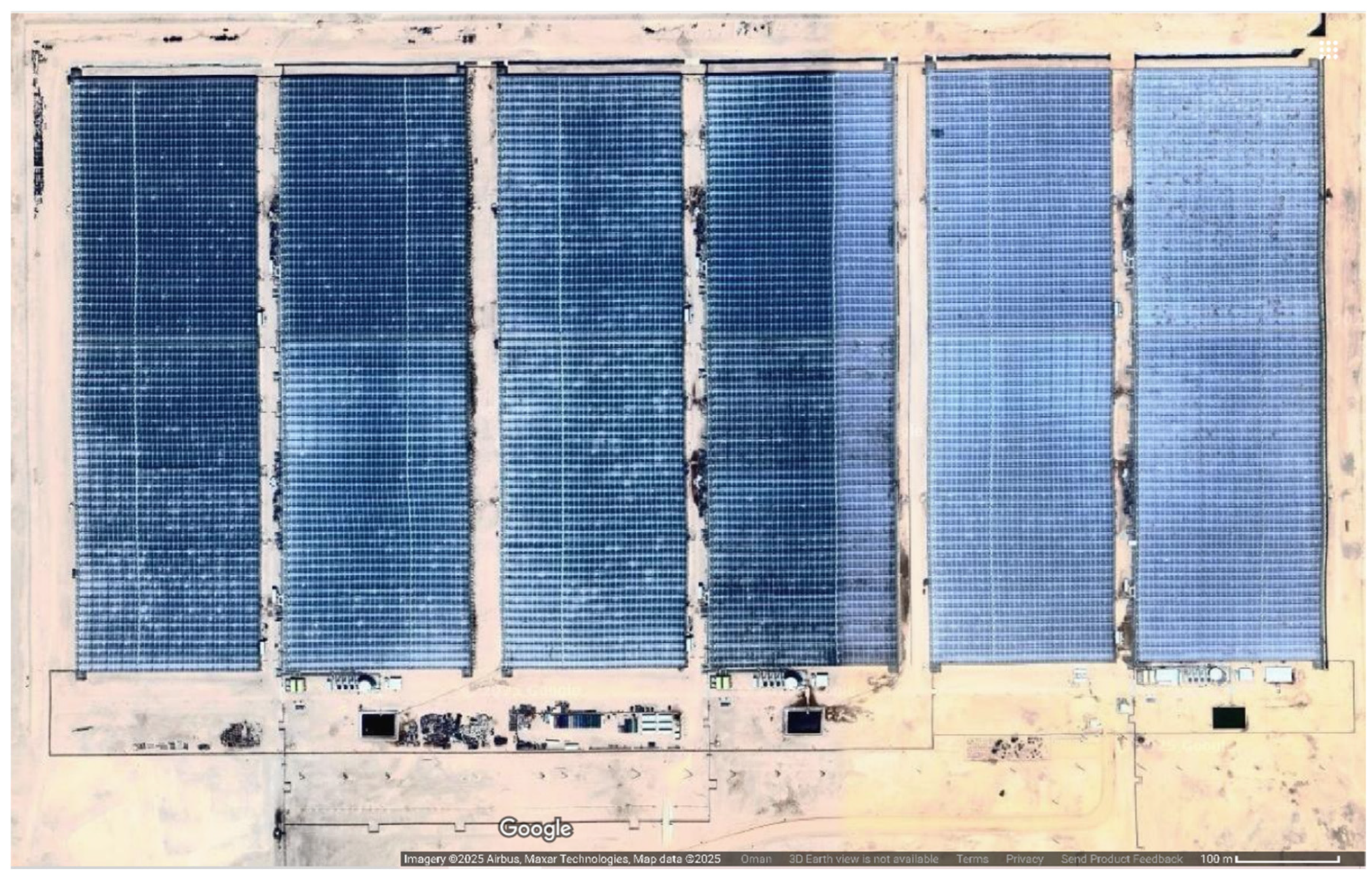

- Google Maps │ Miraah Project. Google Maps. https://maps.app.goo.gl/ZpMJPj7A2S2ZSNZL6 (accessed 2025-08-02).

- GlassPoint. Aerial drone photo of the Miraah project in Oman. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/91913927-47bf-43ab-af89-ce55b5ff5bce/Miraah_drone.jpg (accessed 2025-05-24).

- GlassPoint. Front photo of the Miraah project in Oman. https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/622ba70eb380531fbf6cb5df/1647368082815-T4QPLQM1BZGL3R2KXU2W/miraah_hero.jpg (accessed 2025-05-24).

- Google. Google │ Brand Resource Center -Products and Services - Geo Guidelines. Brand Resource Center. https://about.google/brand-resource-center/products-and-services/geo-guidelines (accessed 2025-08-02).

- DOE, [United States Department of Energy]. DOE │ Geothermal Basics (and footprint comparison for different power technologies). https://www.energy.gov/eere/geothermal/geothermal-basics (accessed 2025-06-27).

- Hosseini, M.; Bagheri, H. Improving the Resolution of Solar Energy Potential Maps Derived from Global DSMs for Rooftop Solar Panel Placement Using Deep Learning. Heliyon 2025, 11 (1). [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, R. Management of Solar Energy. Geomatics, Landmanagement and Landscape 2016, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Bierman, B.; O’Donnell, J.; Burke, R.; McCormick, M.; Lindsay, W. Construction of an Enclosed Trough EOR System in South Oman. Energy Procedia 2014, 49, 1756–1765. [CrossRef]

- Munirasu, S.; Haija, M. A.; Banat, F. Use of Membrane Technology for Oil Field and Refinery Produced Water Treatment—A Review. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2016, 100, 183–202. [CrossRef]

- Adjovu, G. E.; Stephen, H.; James, D.; Ahmad, S. Measurement of Total Dissolved Solids and Total Suspended Solids in Water Systems: A Review of the Issues, Conventional, and Remote Sensing Techniques. Remote Sensing 2023, 15 (14), 3534. [CrossRef]

- Heijerick, D. G.; Janssen, C. R.; Coen, W. M. D. The Combined Effects of Hardness, pH, and Dissolved Organic Carbon on the Chronic Toxicity of Zn to D. Magna: Development of a Surface Response Model. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2003, 44 (2), 0210–0217. [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, F.; Souza, M. P. de; Sterzelecki, F. C.; Cipriano, F. dos S.; Cerqueira, V. R.; Martins, M. L. Effect of total hardness of water on juvenile mullets (Mugil Liza) raised in fresh water. Acta Veterinaria Brasilica 2023, 17 (1). [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K. H.; Khadom, A. A. Sodium Sulfite as an Oxygen Scavenger for the Corrosion Control of Mild Steel in Petroleum Refinery Wastewater: Optimization, Mathematical Modeling, Surface Morphology and Reaction Kinetics Studies. Reac Kinet Mech Cat 2020, 129 (2), 1027–1046. [CrossRef]

- Javaherdashti, R.; Nwaoha, C.; Tan, H. Corrosion and Materials in the Oil and Gas Industries; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2016.

- Marzouk, O. A. Cantera-Based Python Computer Program for Solving Steam Power Cycles with Superheating. International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering 2023, 13 (3), 63–73.

- Redowan, M.; Sami, T. M.; Islam, A. Design and Implementation of Solar Heater System. Thesis, Bachelor of Science in Electrical and Electronic Engineering, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/10361/7727 (accessed 2025-08-03).

- Biencinto, M.; González, L.; Valenzuela, L. Using Time-Windowed Solar Radiation Profiles to Assess the Daily Uncertainty of Solar Thermal Electricity Production Forecasts. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 379, 134821. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Airfoil Design Using Genetic Algorithms. In The 2007 International Conference on Scientific Computing (CSC’07), The 2007 World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (WORLDCOMP’07); CSREA Press: Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2007; pp 127–132.

- Azzouzi, M. Control of Solar Water Heater Design. In 2011 10th International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering; 2011; pp 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Flow Control Using Bifrequency Motion. Theoretical and Computational Fluid Dynamics 2011, 25 (6), 381–405. [CrossRef]

- Alaskaree, E. H.; Breesam, Y. F. The Impact of Electronic Control Systems on Improving the Performance of the Solar Heater. Engineering and Technology Journal 2024, 42 (7), 869–884.

- Zou, Y.; Li, C. A Hydraulically Activated Power Launching Method for Pigs for Gas-Gathering Pipeline Networks in Gas Fields. Journal of Pipeline Systems Engineering and Practice 2022, 13 (2), 04022007. [CrossRef]

- Beavers, J.; Bubenik, T. A. 12 - Stress Corrosion Cracking. In Trends in Oil and Gas Corrosion Research and Technologies; El-Sherik, A. M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing: Boston, 2017; pp 295–314. [CrossRef]

- Katona, R. M.; Taylor, J. M.; McCready, T. A.; Bryan, C. R.; Schaller, R. F. Towards Understanding Stress Corrosion Cracking of Austenitic Stainless Steels Exposed to Realistic Sea Salt Brines. Corrosion Science 2024, 232, 111992. [CrossRef]

- SSINA, [Specialty Steel Industry of North America]. SSINA │ Chloride Stress Corrosion Cracking. https://www.ssina.com/education/corrosion/chloride-stress-corrosion-cracking/ (accessed 2025-08-03).

- Venkatramani, A. V.; Okuno, R. Steam-Oil Ratio in Steam-Solvent Coinjection Simulation for Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Bitumen Reservoirs. J. Energy Resour. Technol 2018, 140 (112903). [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J. O.; Adeniyi, A. G. Factor Effects and Interactions in Steam Reforming of Biomass Bio-Oil. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74 (5), 1459–1470. [CrossRef]

- Hart, A.; Leeke, G.; Greaves, M.; Wood, J. Downhole Heavy Crude Oil Upgrading Using CAPRI: Effect of Steam upon Upgrading and Coke Formation. Energy Fuels 2014, 28 (3), 1811–1819. [CrossRef]

- SLB, [Schlumberger Limited]. SLB │ Steam-Oil Ratio. https://glossary.slb.com/terms/s/steam-oil_ratio (accessed 2025-10-31).

- GER, [General Energy Recovery Inc.]. GER │ Steaming – Reducing Water Usage Through Improved Steam-to-Oil Ratio (SOR). https://www.geri.com/news/steam_to_oil_reduced_water_usage/ (accessed 2025-10-31).

- Goyal, K. L.; Kumar, S. Chapter 11 Steamflooding for Enhanced Oil Recovery. In Developments in Petroleum Science; Donaldson, E. C., Chilingarian, G. V., Yen, T. F., Eds.; Enhanced Oil Recovery, II; Elsevier, 1989; Vol. 17, pp 317–349. [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.-S.; Wang, Y.-M.; Kang, Y.-L.; Jia, Y.-L. A Steam Rising Model of Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage Production for Heavy Oil Reservoirs. Energy Exploration & Exploitation 2020, 38 (4), 801–818. [CrossRef]

- Adibhatla, S.; Kaushik, S. C. Energy, Exergy and Economic (3E) Analysis of Integrated Solar Direct Steam Generation Combined Cycle Power Plant. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2017, 20, 88–97. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Baeyens, J.; Cáceres, G.; Degrève, J.; Lv, Y. Thermal Energy Storage: Recent Developments and Practical Aspects. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2016, 53, 1–40. [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L. F. 2 - Advances in Thermal Energy Storage Systems: Methods and Applications. In Advances in Thermal Energy Storage Systems (Second Edition); Cabeza, L. F., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing, 2021; pp 37–54. [CrossRef]

- Werner, S. International Review of District Heating and Cooling. Energy 2017, 137, 617–631. [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P. A.; Chang, M.; Werner, S.; Svendsen, S.; Sorknæs, P.; Thorsen, J. E.; Hvelplund, F.; Mortensen, B. O. G.; Mathiesen, B. V.; Bojesen, C.; Duic, N.; Zhang, X.; Möller, B. The Status of 4th Generation District Heating: Research and Results. Energy 2018, 164, 147–159. [CrossRef]

- Karni, J. SOLAR-THERMAL POWER GENERATION. Annual Review of Heat Transfer 2012, 15. [CrossRef]

- Tsoutsos, T.; Gekas, V.; Marketaki, K. Technical and Economical Evaluation of Solar Thermal Power Generation. Renewable Energy 2003, 28 (6), 873–886. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Sharma, A. K.; Mullick, S. C.; Kandpal, T. C. Assessment of Solar Thermal Power Generation Potential in India. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 42, 902–912. [CrossRef]

- Kamfa, I.; Fluch, J.; Bartali, R.; Baker, D. Solar-Thermal Driven Drying Technologies for Large-Scale Industrial Applications: State of the Art, Gaps, and Opportunities. International Journal of Energy Research 2020, 44 (13), 9864–9888. [CrossRef]

- Eswara, A. R.; Ramakrishnarao, M. Solar Energy in Food Processing—a Critical Appraisal. J Food Sci Technol 2013, 50 (2), 209–227. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Goel, V.; Karakilcik, M. Solar Food Processing and Cooking Methodologies. In Applications of Solar Energy; Tyagi, H., Agarwal, A. K., Chakraborty, P. R., Powar, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp 251–294. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Hong, T.; Koo, C. An Economic Impact Analysis of State Solar Incentives for Improving Financial Performance of Residential Solar Photovoltaic Systems in the United States. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 58, 590–607. [CrossRef]

- Sarzynski, A.; Larrieu, J.; Shrimali, G. The Impact of State Financial Incentives on Market Deployment of Solar Technology. Energy Policy 2012, 46, 550–557. [CrossRef]

- Matisoff, D. C.; Johnson, E. P. The Comparative Effectiveness of Residential Solar Incentives. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 44–54. [CrossRef]

| Energy sector | Category 1 (largest) | Category 2 (intermediate) | Category 3 (smallest) |

| DEP (total: 3,759,259 TJ) |

crude oil | natural gas | wind and solar |

| 59.3% | 40.6% | 0.1% | |

| 2,230,003 TJ | 1,525,393 TJ | 3,863 TJ | |

| TES (total: 1,161,992 TJ) |

natural gas | crude oil | wind and solar |

| 88.1% | 11.5% | 0.3% | |

| 1,023,964 TJ | 134,165 TJ | 3,863 TJ | |

| Electricity generation (total: 42,771 GWh or 153,975.6 TJ) |

natural gas | crude oil | wind and solar |

| 94.7% | 2.8% | 2.5% | |

| 40,508 GWh (145,828.8 TJ) |

1,190 GWh (4,284 TJ) |

1,073 GWh (3,862.8 TJ) |

|

| TFC (total: 1,060,813 TJ) |

natural gas | oil products | electricity |

| 56.6% | 31.1% | 12.3% | |

| 600,340 TJ | 330,230 TJ | 130,243 TJ |

| Property | Values | ||

| Saturated Liquid | Saturated vapor | Wet steam, 80% quality | |

| Pressure | 100 bar | 100 bar | 100 bar |

| Temperature | 311.06 °C | 311.06 °C | 311.06 °C |

| Density | 688.7052 kg/m3 | 55.4754 kg/m3 | 67.9754 kg/m3 |

| Specific volume | 0.001452 m3/kg | 0.018026 m3/kg | 0.0147112 m3/kg |

| Specific internal energy* | 1393.04 kJ/kg | 2544.4 kJ/kg | 2314.128 kJ/kg |

| Specific enthalpy [102]* | 1407.56 kJ/kg | 2724.7 kJ/kg | 2461.272 kJ/kg |

| Specific entropy* | 3.3596 kJ/kg.K | 5.6141 kJ/kg.K | 5.1632 kJ/kg.K |

| Property | Amal I | Amal II | Miraah |

| 1. Scale/purpose | Pilot | Pilot | Commercial |

| 2. Thermal power capacity | 8 MWth | 8 MWth | 330 MWth (initially planned as 1,021 MWth) |

| 3. Annual heat energy output | 12 GWh/year | 12 GWh/year | 445 GWh/year |

| 4. Average daily steam output | 50 tonnes | 50 tonnes | 2,000 tonnes |

| 5. Solar field area | 17,280 m2 | 17,280 m2 | 622,080 m2 |

| 6. Total project area | 46,200 m2 | 46,200 m2 | 781,200 m2 |

| 7. Current status (as of mid-2025) | Dismantled | Dismantled | Operational (by PDO) |

| 8. Construction starting year | 2011 | 2018 | 2015 |

| 9. Steam production starting year | 2012 | 2020 | 2017 |

| 10. Receiver tube evacuation | No | Yes | No |

| 11. Number of trough rows and reflector mirrors |

12 rows (3 mirrors per row) |

16 rows (1 mirror per row) |

3 modules (18 loops per module) (8 rows and 24 mirrors per loop) Thus, total: 432 rows (3 mirrors per row; thus, 1,296 mirrors) |

| 12. Trough row size (length × aperture width) |

60 m × 7.65 m | 50 m × 7.32 m | 60 m × 7.65 m |

| 13. Shape of the greenhouse roof |

gable | curve | gable |

| 14. Annual natural gas savings | 47,437 MMBtu/year (474,370 therms/year) (13.902 GWh/year) (0.05005 PJ/year) (0.047437 Bcf/year) (1.3553 MNm3/year) |

47,437 MMBtu/year (474,370 therms/year) (13.902 GWh/year) (0.05005 PJ/year) (0.047437 Bcf/year) (1.3553 MNm3/year) |

1,897,461 MMBtu/year (18,974,610 therms/year) (556.091 GWh/year) (2.00193 PJ/year) (1.897461 Bcf/year) (54.2132 MNm3/year) |

| 15. Annual CO2 emissions avoided |

2,514 tonnes/year | 2,514 tonnes/year | 100,565 tonnes/year |

| References | [181,182,183] | [184] | [185,186] |

| Unit | Summed annual avoided NG (three projects together) |

| MMBtu/year | 1,992,335 |

| therms/year | 19,923,350 |

| GWh/year | 569.993 |

| PJ/year | 2.05198 |

| Bcf/year | 1.992335 |

| MNm3/year | 56.9238 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).