Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Groundnut is an essential legume crop vital for global food security, especially in resource-limited areas. However, poor soil fertility and climate change often hinder crop growth in Africa, resulting in low yields, particularly on smallholder farms. This study systematically evaluates, for the first time in the North West Province of South Africa, the inter-annual variations in symbiotic nitrogen fixation and water use efficiency among four major groundnut varieties during the 2023 and 2024 cropping seasons, using 15N and 13C natural abundance techniques. Significant differences were observed in plant growth, nitrogen content, δ15N, %Ndfa, N-fixed, soil N uptake, and grain yield across both years. Groundnut varieties derived 35.51% to 85.77% of their nitrogen from symbiotic fixation, contributing 22.13 to 168.48 kg of nitrogen fixed per hectare. The grain yield was much higher (4305.45 to 7465.91 kg ha−1) in 2024 cropping season compared to (514.73 to 1207.95 kg ha−1) in the 2023 cropping season. The shoot 13C values for the groundnut varieties ranged from −28.57‰ to −28.19‰ in 2023 and −30.17‰ to −28.34‰ in 2024. Notably, varieties Kwarts (85.77%) and Shubert (82.95% demonstrated higher symbiotic dependency in 2023 cropping season, whiles varieties ARC K6 (106.86 kg ha−1) and PC 474 (164.48 kg ha−1) fixed the most N in the 2024 cropping season, along with better water-use efficiency. These varieties namely Kwarts, Shubert, and PC 474 show promise for inclusion in future breeding programs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Sampling and Processing

2.2. Measurement of Shoot N2 Fixation and C Accumulation

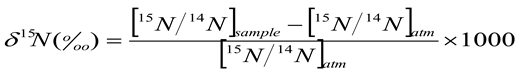

2.2.1. 15N/14N Isotopic Analysis

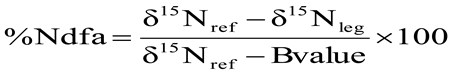

2.2.2. Nitrogen Derived from the Atmosphere (%Ndfa)

2.2.3. Shoot N Content

2.2.4. Amount of N-Fixed

2.2.5. Soil N Uptake

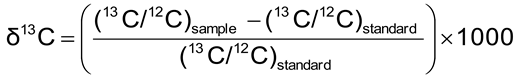

2.2.6. 13C/12C Isotopic Analysis

2.2.7. Carbon Content

2.2.8. C/N Ratio

2.2.9. Determination of Grain Yield

2.2.10. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Properties of Soil Analysis

3.2. Shoot δ15N of Reference Plants

3.3. Plant Growth and Nodulation

3.4. N Concentration and N Content

3.5. Shoot δ15N, %Ndfa and N-Fixed

3.6. Soil N Uptake and Grain Yield

3.7. Shoot C Concentration (%C) and C Content

3.8. Shoot C/N Ratio and δ13C

3.9. Correlation Analysis of Groundnut Varieties in 2023 and 2024

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARC-GCI | Agricultural Research Council-Grain Crops Institute |

| Ca | Calcium |

| Cu | Copper |

| Fe | Iron |

| K | Potassium |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| Mn | Manganese |

| N | Nitrogen |

| N2 | Di-Nitrogen |

| Na | Sodium |

| %Ndfa | Nitrogen derived from the atmosphere |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| NRF | National Research Foundation |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| P | Phosphorus |

| Ph | Potential Hydrogen |

| RCBD | Randomised Complete Design Block |

| S | Sulphur |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| TUT | Tshwane University of Technology |

| WUE | Water-use efficiency |

| Zn | Zinc |

References

- Abady, S.; Shimelis, H.; Janila, P.; Mashilo, J. Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) improvement in sub-Saharan Africa: A review. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2019, 69, 528–545. [Google Scholar]

- Liliane, T.N.; Charles, M.S. Factors affecting yield of crops. Agron.—Clim. Change Food Secur. 2020, 9, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede, E. Contribution, utilization, and improvement of legumes-driven biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 767998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A.; Ibañez, F.; Wang, J.; Guo, B.; Sudini, H.K.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; DasGupta, M. Molecular basis of root nodule symbiosis between Bradyrhizobium and ‘crack-entry’legume groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plants 2020, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.; Adzawla, W.; Pandey, R.; Atakora, W.K.; Kouame, A.K.; Jemo, M.; Bindraban, P.S. Fertilizers for food and nutrition security in sub-Saharan Africa: An overview of soil health implications. Front. Soil Sci. 2023, 3, 1123931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiemann, T.; Douxchamps, S. Opportunities and challenges for integrated smallholder farming systems to improve soil nutrient management in Southeast Asia. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snapp, S.; Silim, S. Farmer preferences and legume intensification for low nutrient environments. Plant Soil 2002, 245, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyemba, R.C.; Dakora, F.D. Evaluating N2 fixation by food grain legumes in farmers’ fields in three agro-ecological zones of Zambia, using 15 N natural abundance. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2010, 46, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgehle, S.N.; Dakora, F.D.; Mathews, C. Variation in N2 fixation and N contribution by 25 groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) varieties grown in different agro-ecologies, measured using 15N natural abundance. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 195, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngmenzuma, T.Y.; Oteng-frimpong, R.; Dakora, F.D. N2 fixation, grain mineral accumulation, and water-use efficiency in 30 field-grown groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes in Mpumalanga, South Africa, measured using 15N and 13C natural abundance techniques. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1483741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteng-Frimpong, R.; Dakora, F.D. Multienvironment testing for trait stability and G× E interaction on N2 Fixation, plant development, and water-use efficiency of 21 elite groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes in the Guinea Savanna. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 446640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.S.; Das, A.; Yadav, G.S.; Lal, R. (Eds.) Legumes for Soil Health and Sustainable Management; Springer: Singapore, 2018; p. 541. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Nakar, R.; Goswami, N.; Kalariya, K.; Chakraborty, K.; Singh, M. Water deficit stress and its management in groundnut. Physiol. Nutr. Environ. Stress. Crop Product. 2013, 14, 371–465. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, B.M.; Layek, J.; Das, A.; Choudhary, A.K.; Bahar, F.A.; Singh, S.; Mahdi, S. Agronomic interventions for increasing crop productivity and farmer’s income in Indian Himalayas. Indian J. Agron. 2023, 68, S177–S197. [Google Scholar]

- Keteku, A.K.; Yeboah, P.A.; Yeboah, S.; Dormatey, R.; Agyeman, K.; Brempong, M.B.; Ghanney, P.; Poku, S.A.; Danquah, E.O.; Frimpong, F.; et al. Plant nutrition in relation to water-use efficiency in crop production: A review. Agrica 2024, 17, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, M.; Sarkar, S.; Era, F.M.; Islam, A.M.; Anwar, M.P.; Fahad, S.; Datta, R.; Islam, A.A. Drought stress in grain legumes: Effects, tolerance mechanisms and management. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DWAF. Report of the Department of Water Affair and Forestry; Department of Water Affair and Forestry: Pretoria, South Africa, 2002; Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/dwaf-ar-2002.pdf(accessed on).

- DAFF. A Profile of the South African Groundnut; Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015; Available online: http://webapps1.daff.gov.za/AmisAdmin/upload/Groundnut%20profile%2014/2015.pdf(accessed on).

- Lottering, S.; Mafongoya, P.; Lottering, R. Drought and its impacts on small-scale farmers in sub-Saharan Africa: A review. South Afr. Geogr. J. 2021, 103, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settaluri, V.; Kandala, C.; Puppala, N.; Sundaram, J. Peanuts and their nutritional aspects—A review. Food Nutr. Sci. 2012, 3, 1644–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querejeta, J.I.; Ren, W.; Prieto, I. Vertical decoupling of soil nutrients and water under climate warming reduces plant cumulative nutrient uptake, water-use efficiency and productivity. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1378–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusiba, S.G.; Maseko, S.T.; Odhiambo, J.J.O.; Adeleke, R. Biological N2 fixation, C accumulation and water-use efficiency (δ13C) of chickpea grown in three different soil types: Response to the addition of biochar from poultry litter and acacia. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2022, 72, 931–944. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, G.D.; Ehleringer, J.R.; Hubick, K.T. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1989, 40, 503–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Schnyder, H.; Cuntz, M.; Keitel, C.; Zeeman, M.J.; Dawson, T.; Badeck, F.-W.; BrugnolI, E.; Ghashghaie, J.; Grams, T.E. Progress and challenges in using stable isotopes to trace plant carbon and water relations across scales. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 3083–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Macko, S.A.; Shugart, H.H. Patterns in N dynamics and N isotopes during primary succession in Glacier Bay, Alaska. Chem. Geol. 1998, 152, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaschuk, G.; Kuyper, T.W.; LeffelaaR, P.A.; Hungria, M.; Giller, K.E. Are the rates of photosynthesis stimulated by the carbon sink strength of rhizobial and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J.; Asakawa, N. Decomposition of leaf litter from tropical forage grasses and legumes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1993, 25, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchobanoglous, G.; Theisen, H.; Vigil, S. Integrated Solid Waste Management, Engineering Principles and Management Issues; McGraw-Hill Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Norbu, T.; Visvanathan, C.; Basnayake, B. Pretreatment of municipal solid waste prior to landfilling. Waste Manag. 2005, 25, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, S.E. Effects of plant species on nutrient cycling. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1992, 7, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cui, Z.; Fan, M.; Vitousek, P.; Zhao, M.; Ma, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yan, X.; Yang, J. Producing more grain with lower environmental costs. Nature 2014, 514, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeh, E.L.; Ngmenzuma, T.Y.; Maseko, S.T.; Nyila, M.A.; Kanu, S.A.; Mohale, K.C. Gas exchange and carbon assimilation of Bambara groundnut landraces co-inoculated with Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Bacillus subtilis under simulated drought stress. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, e01823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, A.T. The synergic effects of climate variability on rainfall distribution over Hare catchment of Ethiopia. Adv. Meteorol. 2023, 1175426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, A.; Zapata, F.; Kumarasinghe, K.S. Carbon isotope discrimination as indicator of water-use efficiency of spring wheat as affected by salinity and gypsum addition. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1999, 30, 2681–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Cai, T. Mechanisms for the relationships between water- use efficiency and carbon isotope composition and specific leaf area of maize (Zea mays L.) under water stress. Plant Growth Regulation 2015, 77, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SANBI. 2024. Available online: https://www.sanbi.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2021_NECS-Handbook.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Mariotti, A.; Germon, J.C.; Hubert, P.; Kaiser, P.; Letolle, R.; Tardieux, A.; Tardieux, P. Experimental determination of nitrogen kinetic isotope fractionation: Some principles; illustration for the denitrification and nitrification processes. Plant Soil 1981, 62, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unkovich, M.; Herridge, D.; Peoples, M.; Cadisch, G.; Boddey, B.; Giller, K.; Alves, B.; Chalk, P. Measuring Plant-Associated Nitrogen Fixation in Agricultural Systems; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR): Canberra, Austalia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer, G.; Kohl, D.H. N2-fixation in field settings: Estimations based on natural 15N abundance. Funct. Plant Biol. 1986, 13, 699–756. [Google Scholar]

- Pausch, R.C.; Mulchi, C.L.; Lee, E.H.; Forseth, I.N.; Slaughter, L.H. Use of 13C and 15N isotopes to investigate O3 effects on C and N metabolism in soybeans. Part I. C fixation and translocation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1996, 59, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, M.J.; Sinclair, T.R.; Vadez, V. Genotypic variability among peanut (Arachis hypogea L.) in sensitivity of nitrogen fixation to soil drying. Plant Soil 2010, 330, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, J.M.; Rowland, D.L.; Payton, P.; Faircloth, W.; Sinclair, T.R. Nitrogen fixation tolerance to soil water deficit among commercial cultivars and breeding lines of peanut. Field Crops Res. 2013, 149, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, A.; Llanes, A.; Luna, V.; Castro, S. Physiological and biochemical responses to drought stress and subsequent rehydration in the symbiotic association peanut-Bradyrhizobium sp. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimratch, S.; Jogloy, S.; Vorasoot, N.; Toomsan, B.; Kesmala, T.; Patanothai, A.; Holbrook, C.C. Effect of drought stress on traits related to N2 fixation in eleven peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes differing in degrees of resistance to drought. Asian J. of. Plant Sci. 2008, 4, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Chen, Y. The physiological response of photosynthesis to nitrogen deficiency. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimratch, S.; Jogloy, S.; Vorasoot, N.; Toomsan, B.; Kesmala, T.; Patanothai, A.; Holbrook, C.C. Heritability of N2 fixation traits, and phenotypic and genotypic correlations between N2 fixation traits with drought resistance traits and yield in peanut. Crop Sci. 2009, 49, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.H.; Marschner, P. Respiration, available N and microbial biomass N in soil amended with mixes of organic materials differing in C/N ratio and decomposition stage. Geoderma 2018, 319, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Macko, S.A.; Williams, M. Correlations between foliar δ15N and nitrogen concentrations may indicate plant-mycorrhizal interactions. Oecologia 2000, 122, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, C.Y.; Dang, P.; Carter, J.; Zhao, S.; Lamb, M.C.; Chu, Y.; Holbrook, C.; Ozias-akins, P.; Isleib, T.G. Variabilities in symbiotic nitrogen fixation and carbon isotope discrimination among peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes under drought stress. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2023, 209, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature | Rainfall | Relative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | (mm) | Humidity | |||

| % | |||||

| 2023 | Min | Max | Min | Max | |

| October | 11.19 | 30.89 | 45.47 | 25.26 | 82.82 |

| November | 14.88 | 32.32 | 52.32 | 29.09 | 88.57 |

| December | 15.91 | 31.49 | 40.39 | 35.66 | 90.61 |

| January | 15.69 | 31.39 | 63.3 | 38.22 | 96.72 |

| Average | 14.42 | 31.51 | 50.37 | 32.06 | 89.68 |

| 2024 | Min | Max | Min | Max | |

| October | 15.43 | 34.06 | 17.78 | 32.11 | 96.82 |

| November | 14.49 | 33.74 | 51.31 | 29.18 | 93.79 |

| December | 9.92 | 27.95 | 161.80 | 35.84 | 97.75 |

| January | 5.29 | 29.26 | 87.12 | 21.26 | 93.38 |

| Average | 11.28 | 31.25 | 79.50 | 29.60 | 95.44 |

| Soil Properties | Units | Measurements | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 2024 | ||

| pH (H2O) | 5.68 | 6.15 | |

| SOC | % | 0.85 | 0.83 |

| Total N | % | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| P | mg kg−1 | 17 | 22 |

| K | mg kg−1 | 200 | 218 |

| Na | mg kg−1 | 13 | 18 |

| Ca | mg kg−1 | 900 | 923 |

| Mg | mg kg−1 | 358 | 410 |

| S | mg kg−1 | 22 | 6 |

| Fe | mg kg−1 | 9.20 | 9.60 |

| Cu | mg kg−1 | 2.44 | 2.40 |

| Mn | mg kg−1 | 28.26 | 31.60 |

| Zn | mg kg−1 | 4.84 | 6.44 |

| 2023 Cropping Season | 2024 Cropping Season | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Names | Scientific Names | δ15N (‰) | Common Names | Scientific Names | δ15N (‰) |

| Purple Nutsedge | Cyperus rotundus L. | +5.05 | |||

| Dock | Rumex obtusifolius | +5.82 | PurpleNutsedge | Cyperus rotundusL. | +4.06 |

| RoughCocklebur | Xanthiumstrumarium | +5.12 | Goosegrass | Eleusine indica L. | +6.09 |

| Nightshade | Solanum nigrum | +5.39 | Smooth pigweed | Amaranthus hybridus | +5.76 |

| Pigweed | Amaranthus Spp. | +5.95 | Goosegrass | Eleusine indica L. | +5.89 |

| Downy thorn apple | Datura stramonium | +4.57 | Grondsel | Senecio valgaris | +6.27 |

| Horsenette | Solanum Carolinen L. | +5.12 | |||

| Average | 5.145 | Average | 5.814 | ||

| Varieties | Nodule No. | Shoot DM | N Concentration |

N Content | N-Fixed | Ndfa | δ15N | Soil N Uptake | Grain Yield | C Concentration |

C Content |

δ13C | C/N Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| per plant | g plant−1 | % | g plant−1 | kg ha−1 | % | ‰ | kg ha−1 | kg ha−1 | % | g plant−1 | ‰ | g g−1 | |

| Schubert | 14.0 ± 0.65 d | 16.05 ± 1.19 b | 1.76 ± 0.14 a | 0.33 ± 0.01 ab | 35.61 ± 1.74 a | 82.95 ± 0.99 ab | −1.64 ± 0.06 b | 6.42 ± 0.74 b | 1207.95 ± 62.92 a | 39.01 ± 0.50 a | 6.09 ± 0.68 a | −28.30 ± 0.26 a | 22.60 ± 1.65 b |

| Kwarts | 28.0 ± 1.49 a | 18.55 ± 037 a | 1.60 ± 0.22 a | 0.35 ± 0.01 a | 33.05 ± 1.06 ab | 85.77 ± 1.84 a | −0.88 ± 0.78 c | 10.67 ± 1.26 a | 514.73 ± 57.66 d | 35.58 ± 1.79 a | 6.59 ± 0.35 a | −28.19 ± 0.22 a | 23.13 ± 2.22 ab |

| ARC K6 | 25.0 ± 0.65 b | 12.65 ± 0.78 c | 1.22 ± 0.03 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 b | 27.13 ± 0.90 b | 76.56 ± 0.79 b | −2.14 ± 0.17 ab | 2.40 ± 0.08 c | 785.82 ± 20.53 c | 37.49 ± 0.83 a | 4.74 ± 0.31 b | −28.57 ± 0.22 a | 30.76 ± 0.77 a |

| PC 474 | 17.0 ± 1.49 c | 7.27 ± 0.56 d | 1.65 ± 0.05 a | 0.11 ± 0.00 c | 22.13 ± 0.87 c | 58.18 ± 1.53 c | −2.67 ± 0.08 a | 0.41 ± 0.061 d | 812.73 ± 20.33 b | 38.75 ± 0.71 a | 2.82 ± 0.24 c | −28.41 ± 0.16 a | 23.49 ± 0.46 ab |

| F-statistics | 34.03 *** | 38.60 *** | 3.05 ns | 153.66 *** | 25.55 *** | 14.35 *** | 3.60 * | 38.46 *** | 40.16 *** | 2.094 ns | 15.31 *** | 0.54 ns | 7.047 ** |

| Varieties | Nodule No. | Shoot DM | N | N Content | N-Fixed | Ndfa% | δ15N | Soil N Uptake | Grain Yield | C | C Content | δ13C | C/N Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| per plant | g plant−1 | % | g plant−1 | kg ha−1 | ‰ | kg ha−1 | kg ha−1 | % | g plant−1 | ‰ | g g−1 | ||

| Schubert | 13.0 ± 0.63 b | 17.74 ± 0.92 d | 1.56 ± 0.12 b | 0.28 ± 0.02 c | 29.24 ± 1.27 c | 58.63 ± 0.79 a | 3.12 ± 0.65 a | 27.72 ± 1.61 c | 4305.45 ± 365.8 c | 34.76 ± 0.69 b | 6.17 ± 0.35 c | −28.34 ± 0.97 a | 21.23 ± 0.82 a |

| Kwarts | 35.0 ± 0.85 a | 30.64 ± 3.46 c | 1.73 ± 0.08 ab | 0.58 ± 0.07 b | 44.49 ± 1.48 b | 56.24 ± 1.33 ab | 1.46 ± 0.32 b | 64.23 ± 1.49 b | 6349.55 ± 375.7 ab | 39.05 ± 0.39 a | 12.22 ± 1.12 b | −30.17 ± 0.25 a | 21.53 ± 1.65 a |

| ARC K6 | 32.0 ± 1.11 ab | 85.87 ± 3.80 a | 1.75 ± 0.09 ab | 1.44 ± 0.07 ab | 106.86 ± 4.99 ab | 35.51 ± 0.79 c | 3.18 ± 0.06 a | 141.84 ± 2.98 ab | 5424.09 ± 392.9 b | 35.98 ± 1.56 ab | 29.89 ± 1.10 ab | −30.05 ± 0.30 a | 19.18 ± 0.72 a |

| PC 474 | 19.0 ± 0.95 c | 81.57 ± 2.49 ab | 2.07 ± 0.12 a | 1.66 ± 0.09 a | 164.48 ± 1.64 a | 52.53 ± 0.38 b | 2.92 ± 0.41 ab | 177.76 ± 1.11 a | 7465.91 ± 747.3 a | 37.68 ± 0.96 ab | 33.48 ± 1.38 a | −29.17 ± 0.29 a | 21.00 ± 0.73 a |

| F-statistics | 134.87 *** | 144.87 *** | 4.29 * | 95.76 *** | 489.71 *** | 138.72 *** | 3.87 * | 1275.33 *** | 7.32 ** | 3.54 * | 157.66 *** | 22.46 ns | 1.009 ns |

| 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variety | Parameter | R-Value | p-Value |

| Schubert | Shoot DM vs. N content | 0.999 | 0.0001 |

| Shoot DM vs. N-fixed | 0.9592 | 0.041 | |

| Shoot DM vs. C content | 0.97 | 0.03 | |

| N concentration vs. C/N ratio | −0.9849 | 0.015 | |

| N content vs. N-fixed | 0.9659 | 0.034 | |

| N content vs. C content | 0.9708 | 0.029 | |

| Kwarts | N concentration vs. C/N ratio | −0.9807 | 0.019 |

| N content vs. C concentration | 0.9654 | 0.035 | |

| N content vs. C content | 0.9857 | 0.014 | |

| %Ndfa vs. Soil N uptake | 0.9666 | 0.033 | |

| %Ndfa vs. C content | 0.9798 | 0.02 | |

| N-fixed vs. δ13C | −0.9561 | 0.044 | |

| Soil N uptake vs. Grain yield | 0.9933 | 0.007 | |

| ARCK6 | Nodule no. vs. %Ndfa | −0.9802 | 0.02 |

| Nodule no. vs. Soil N uptake | −0.9581 | 0.042 | |

| %Nfa vs. Soil N uptake | 0.9828 | 0.017 | |

| PC474 | Shoot DM vs. N-fixed | 0.9918 | 0.008 |

| Shoot DM vs. Grain yield | −0.9996 | 0.0001 | |

| Shoot DM vs. C content | 0.9805 | 0.02 | |

| N content vs. δ15N | −0.9935 | 0.006 | |

| N-fixed vs. grain yield | −0.99 | 0.01 | |

| N-fixed vs. C content | 0.9702 | 0.03 | |

| Grain yield vs. C content | −0.975 | 0.025 | |

| 2024 | |||

| Variety | parameter | p-value | R-value |

| Shubert | N concentration vs. N-fixed | 0.9532 | 0.047 |

| N content vs. Soil N up take | 1.000 | 0.0001 | |

| N content vs. C concentration | −0.9912 | 0.009 | |

| N content vs. C/N ratio | −0.9723 | 0.028 | |

| %Ndfa vs. C content | −0.9522 | 0.048 | |

| C concentration vs. Soil N uptake | −0.9905 | 0.009 | |

| C concentration vs. C/N ratio | 0.9947 | 0.005 | |

| Kwarts | Shoot DM vs. C content | 0.9869 | 0.013 |

| Shoot DM vs. N content | 0.952 | 0.045 | |

| N content vs. C/N ratio | −0.9567 | 0.043 | |

| δ15N vs. %Ndfa | −0.9857 | 0.014 | |

| ARC K6 | Shoot DM vs. N content | 0.952 | 0.048 |

| N content vs. %Ndfa | −0.988 | 0.012 | |

| N content vs. C content | 0.9586 | 0.041 | |

| Grain yield vs. C/N ratio | 0.9721 | 0.028 | |

| δ13C vs. C content | 0.977 | 0.023 | |

| PC 474 | δ15N vs. Grain yield | −0.9982 | 0.002 |

| δ15 vs. C/N ratio | 0.9562 | 0.044 | |

| %Ndfa vs. Soil N uptake | 0.9815 | 0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).