Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. NGS Techniques

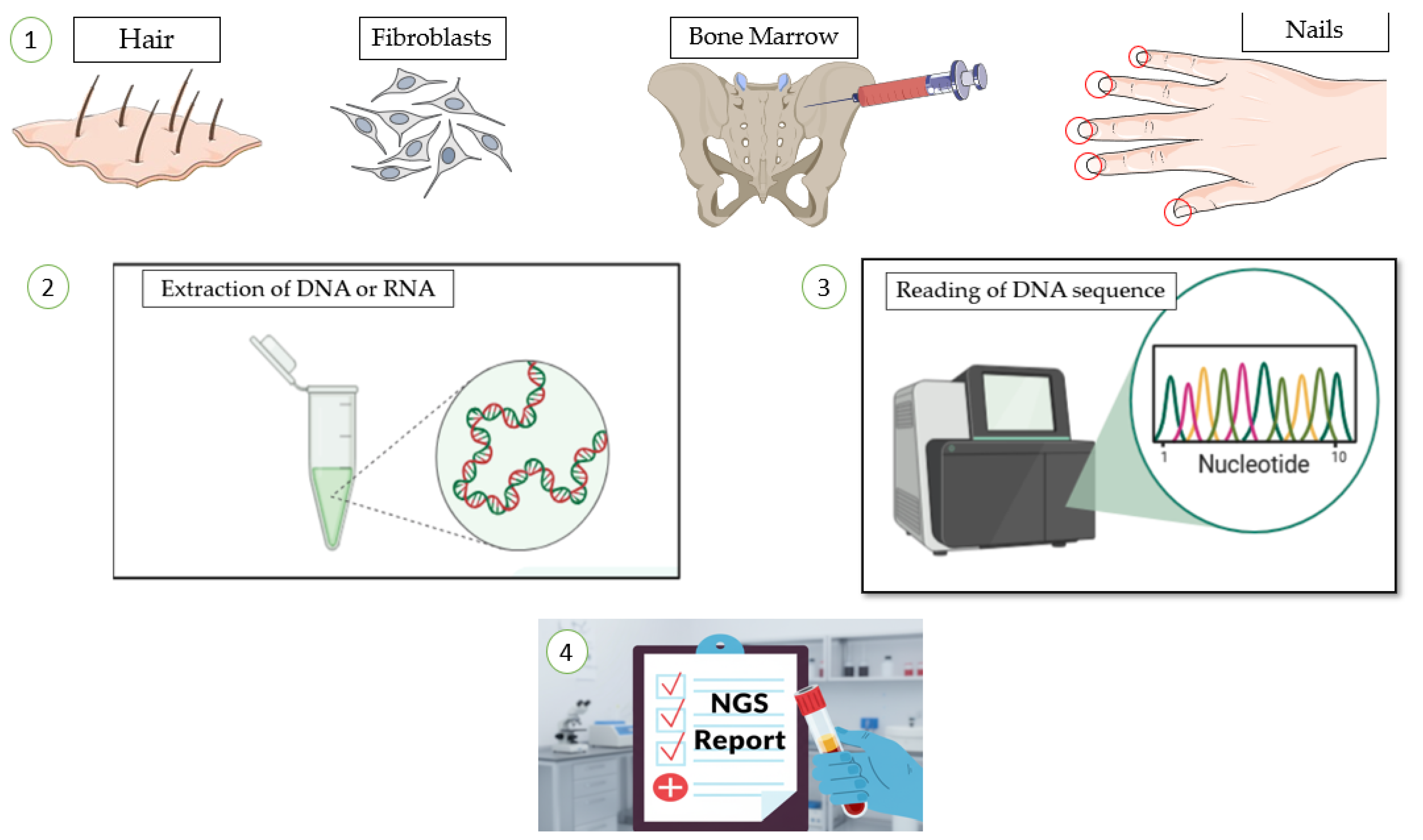

2.1. NGS Workflow

2.2. NGS Types in Clinical Practice

2.3. Sample Type and Quantity

2.4. Results Validation

2.5. Standardization

2.6. Type of Alterations

2.7. Result Interpretation

2.8. Useful Database

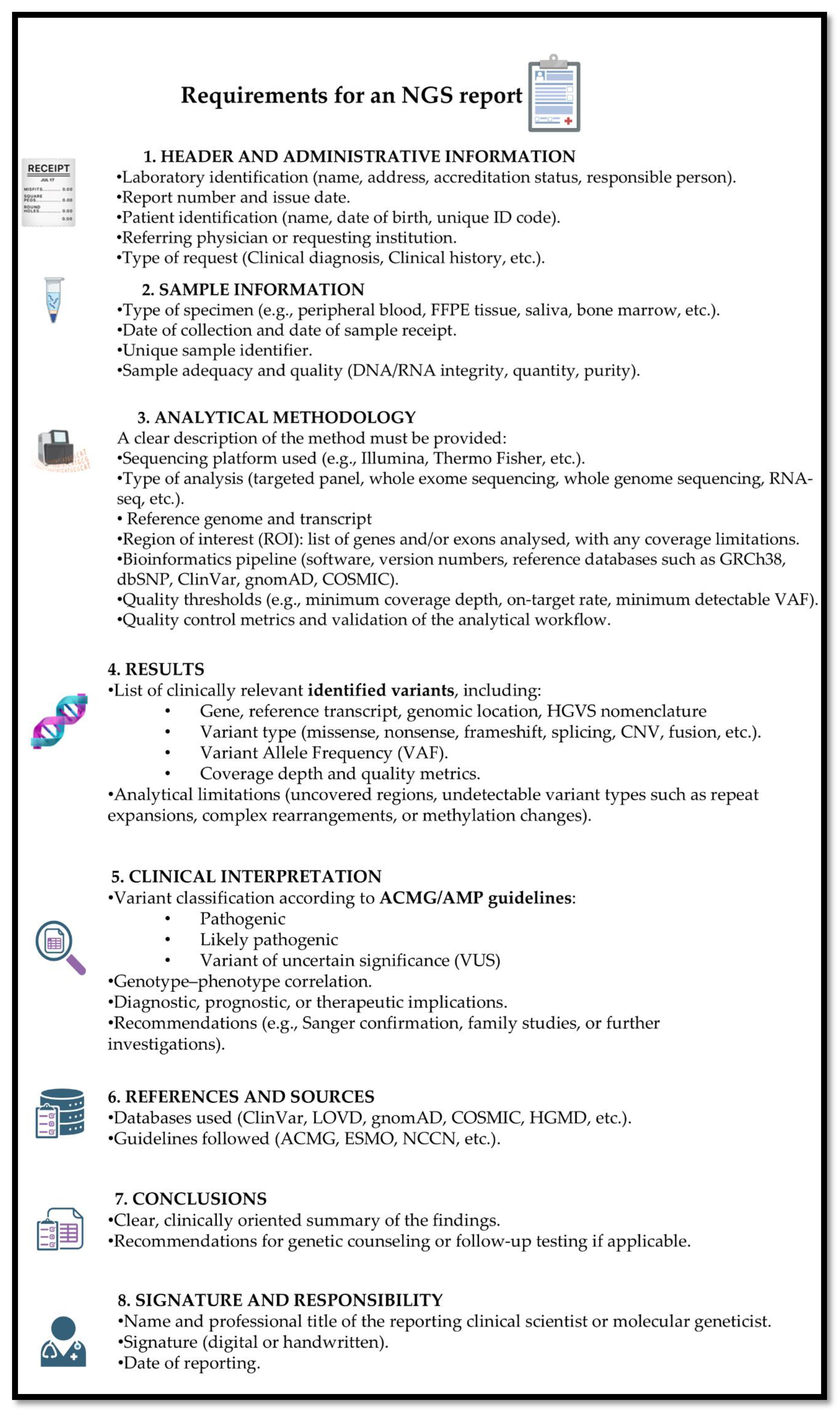

2.9. Report Structure

2.10. NGS vs. Quantitative-PCR vs. Digital-PCR

3. NGS and Impact on Diagnosis and Classification

3.1. NGS Role in MDS: From Diagnosis to Classification

3.2. CHIP and CCUS, the Role of NGS

3.3. Novel Genetically-Based Categories in MDS

3.3.1. SF3B1 in MDS

3.3.2. TP53 in MDS

3.4. Impact of NGS in the Definition of AML, Novel Genetic Classifications

3.4.1. TP53 Mutations in AML

3.4.2. MDS-Related Mutations

3.4.3. RUNX1

3.4.4. AML-Defining Mutations

3.5. AML Mutations Driving Target Therapies (IDH1/2 and FLT3)

4. NGS and Impact on Risk Stratification

4.1. Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Prognostic Impact of Molecular Data

4.2. Acute Myeloid Leukemia

4.2.1. Stratification of AML for Patients Treated with less-Intensive Therapy

6. The Role of NGS in the Detection of Germline Predisposition [132]

6.1. DDX41

6.2. TP53

6.3. GATA2

6.4. RUNX1

6.5. ETV6

7. The Impact of NGS in the Detection of Druggable Mutations at Relapse

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

10. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| CCUS | Clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance |

| CHIP | Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential |

| HSCT | Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| ICC | International Consensus Conference |

| MDS | Myelodysplastic neoplasms |

| MN | Myeloid neoplasms |

| MRD | Measurable residual disease |

| NGS | Next generation sequencing |

| SBS | Sequencing by synthesis |

| VAF | Variant allele frequencies |

| VUS | Variants of uncertain significance |

| WES | Whole exome sequencing |

| WGS | Whole genome sequencing |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Papaemmanuil, E.; Gerstung, M.; Bullinger, L.; Gaidzik, V.I.; Paschka, P.; Roberts, N.D.; Potter, N.E.; Heuser, M.; Thol, F.; Bolli, N.; et al. Genomic Classification and Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 374, 2209–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, J.D.; Solary, E.; Abla, O.; Akkari, Y.; Alaggio, R.; Apperley, J.F.; Bejar, R.; Berti, E.; Busque, L.; Chan, J.K.C.; et al. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of AML in Adults: 2022 Recommendations from an International Expert Panel on Behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooptu, M.; Murdock, H.M.; Soiffer, R.J. How I Treat AML Relapse after Allogeneic HSCT. Blood 2025, 145, 2128–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.; Jochum, W.; Padberg, B.; Demmer, I.; Mertz, K.D.; Joerger, M.; Britschgi, C.; Matter, M.S.; Rothschild, S.I.; Omlin, A. How to Read a Next-Generation Sequencing Report—What Oncologists Need to Know. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, M.F.; Westphalen, C.B.; Stenzinger, A.; Barlesi, F.; Bayle, A.; Bièche, I.; Bonastre, J.; Castro, E.; Dienstmann, R.; Krämer, A.; et al. Recommendations for the Use of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for Patients with Advanced Cancer in 2024: A Report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Annals of Oncology 2024, 35, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Takahashi, K. Emerging Technologies of Single-Cell Multi-Omics. Haematologica 2025, 110, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, L.J.; Arcila, M.E.; Corless, C.; Kamel-Reid, S.; Lubin, I.M.; Pfeifer, J.; Temple-Smolkin, R.L.; Voelkerding, K.V.; Nikiforova, M.N. Guidelines for Validation of Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Oncology Panels: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology and College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn 2017, 19, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncavage, E.J.; Bagg, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; DiNardo, C.D.; Godley, L.A.; Iacobucci, I.; Jaiswal, S.; Malcovati, L.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Patel, K.P.; et al. Genomic Profiling for Clinical Decision Making in Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemia. Blood 2022, 140, 2228–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, S.R.; Komori, H.K.; LaMere, S.A.; Whisenant, T.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.; Salomon, D.R.; Ordoukhanian, P. Library Construction for Next-Generation Sequencing: Overviews and Challenges. Biotechniques 2014, 56, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y. The Principles and Applications of High-Throughput Sequencing Technologies. Dev Reprod 2023, 27, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, S.; McPherson, J.D.; McCombie, W.R. Coming of Age: Ten Years of next-Generation Sequencing Technologies. Nat Rev Genet 2016, 17, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peroni, E.; Randi, M.L.; Rosato, A.; Cagnin, S. Acute Myeloid Leukemia: From NGS, through scRNA-Seq, to CAR-T. Dissect Cancer Heterogeneity and Tailor the Treatment. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2023, 42, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.E.; Shaw, R.; Madero-Marroquin, R.; Roloff, G.W. Clinical Considerations at the Intersection of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and Hereditary Hematopoietic Malignancy. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1180439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Sukhai, M.A.; Zhang, T.; Dolatshahi, R.; Harbi, D.; Garg, S.; Misyura, M.; Pugh, T.; Stockley, T.L.; Kamel-Reid, S. Integration of Technical, Bioinformatic, and Variant Assessment Approaches in the Validation of a Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Panel for Myeloid Malignancies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017, 141, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akabari, R.; Qin, D.; Hussaini, M. Technological Advances: CEBPA and FLT3 Internal Tandem Duplication Mutations Can Be Reliably Detected by Next Generation Sequencing. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumbo, C.; Minervini, C.F.; Orsini, P.; Anelli, L.; Zagaria, A.; Minervini, A.; Coccaro, N.; Impera, L.; Tota, G.; Parciante, E.; et al. Nanopore Targeted Sequencing for Rapid Gene Mutations Detection in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, P.E.; Sebra, R.P. Long-Read DNA Sequencing: Recent Advances and Remaining Challenges. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2023, 24, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakli, E.; Christopoulos, P.; Potiris, A.; Zikopoulos, A.; Mavrogianni, D.; Karampas, G.; Kathopoulis, N.; Anagnostaki, I.; Domali, E.; Tzallas, A.T.; et al. Long-Read Sequencing and Structural Variant Detection: Unlocking the Hidden Genome in Rare Genetic Disorders. Diagnostics (Basel) 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.; Sudbery, I.; Ilott, N.E.; Heger, A.; Ponting, C.P. Sequencing Depth and Coverage: Key Considerations in Genomic Analyses. Nat Rev Genet 2014, 15, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anu, R.I.; Patel, A.; Pathak, N.; Mehta, P.; Chougule, A.; Sheth, H.; Veldore, V.; Suryavanshi, M.; Gupta, V.G.; Disel, U.; et al. Uniform Reporting of Next Generation Sequencing: Indian Society of Medical and Pediatric Oncology. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2025, 46, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, A.; Madrigal, P.; Tarazona, S.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Cervera, A.; McPherson, A.; Szczesniak, M.W.; Gaffney, D.J.; Elo, L.L.; Zhang, X.; et al. A Survey of Best Practices for RNA-Seq Data Analysis. Genome Biol 2016, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, L.W.; Hayati, S.; Roloff, G.W.; Tunc, I.; Pirooznia, M.; Mitrofanova, A.; Hourigan, C.S. Targeted RNA-Sequencing for the Quantification of Measurable Residual Disease in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Haematologica 2019, 104, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, A.C.C.; Sadee, W.; Johnson, J.A. Whole Transcriptome Profiling: An RNA-Seq Primer and Implications for Pharmacogenomics Research. Clin Transl Sci 2018, 11, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarella, A.; Williams, C.R.; Parrish, J.Z.; Kim, C.C. Empirical Assessment of the Impact of Sample Number and Read Depth on RNA-Seq Analysis Workflow Performance. BMC Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.T.; Choi, Y.L.; Yun, J.W.; Kim, N.K.D.; Kim, S.Y.; Jeon, H.J.; Nam, J.Y.; Lee, C.; Ryu, D.; Kim, S.C.; et al. Prevalence and Detection of Low-Allele-Fraction Variants in Clinical Cancer Samples. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrackova, A.; Vasinek, M.; Sedlarikova, L.; Dyskova, T.; Schneiderova, P.; Novosad, T.; Papajik, T.; Kriegova, E. Standardization of Sequencing Coverage Depth in NGS: Recommendation for Detection of Clonal and Subclonal Mutations in Cancer Diagnostics. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.R. Target Enrichment Approaches for Next-Generation Sequencing Applications in Oncology. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kateb, H.; Knight, S.M.; Sivasankaran, G.; Voss, J.S.; Pitel, B.A.; Blommel, J.H.; Jerde, C.R.; Rumilla, K.M.; Lee, J.L.; Mattson, N.R.; et al. Clinical Validation of the TruSight Oncology 500 Assay for the Detection and Reporting of Pan-Cancer Biomarkers. J Mol Diagn 2025, 27, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahajpal, N.S.; Mondal, A.K.; Ananth, S.; Njau, A.; Ahluwalia, P.; Jones, K.; Ahluwalia, M.; Okechukwu, N.; Savage, N.M.; Kota, V.; et al. Clinical Performance and Utility of a Comprehensive Next-Generation Sequencing DNA Panel for the Simultaneous Analysis of Variants, TMB and MSI for Myeloid Neoplasms. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0240976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrati, S.; De Summa, S.; Pilato, B.; Petriella, D.; Lacalamita, R.; Tommasi, S.; Pinto, R. Next-Generation Sequencing: Advances and Applications in Cancer Diagnosis. Onco Targets Ther 2016, 9, 7355–7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koboldt, D.C. Best Practices for Variant Calling in Clinical Sequencing. Genome Med 2020, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.Y.; Ding, L.W.; Tan, K.T.; Chien, W.; Mayakonda, A.; Lin, D.C.; Loh, X.Y.; Xiao, J.F.; Meggendorfer, M.; Alpermann, T.; et al. Ordering of Mutations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia with Partial Tandem Duplication of MLL (MLL-PTD). Leukemia 2017, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, D.H.; Abel, H.J.; Lockwood, C.M.; Payton, J.E.; Szankasi, P.; Kelley, T.W.; Kulkarni, S.; Pfeifer, J.D.; Duncavage, E.J. Detection of FLT3 Internal Tandem Duplication in Targeted, Short-Read-Length, next-Generation Sequencing Data. J Mol Diagn 2013, 15, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Diaz, A.; Vazquez, I.; Ariceta, B.; Manu, A.; Blasco-Iturri, Z.; Palomino-Echeverria, S.; Larrayoz, M.J.; Garcia-Sanz, R.; Prieto-Conde, M.I.; Del Carmen Chillon, M.; et al. Assessment of the Clinical Utility of Four NGS Panels in Myeloid Malignancies. Suggestions for NGS Panel Choice or Design. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, M.; Shi, W.; Chang, K.; Laing, C.; Pollner, R.; Gocke, C.; Adams, E.; Berisha, F.; Lameh, J.; Lesegretain, A. FLT3 Inhibitors Added to Induction Therapy Induce Deeper Remissions. Blood 2020, 135, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keegan, A.; Bridge, J.A.; Lindeman, N.I.; Long, T.A.; Merker, J.D.; Moncur, J.T.; Montgomery, N.D.; Nagarajan, R.; Rothberg, P.G.; Routbort, M.J.; et al. Proficiency Testing of Standardized Samples Shows High Interlaboratory Agreement for Clinical Next Generation Sequencing-Based Hematologic Malignancy Assays With Survey Material-Specific Differences in Variant Frequencies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, T.G.; Lee, S.; Shin, S.; Lee, S.T. A Comparative Study of Next-Generation Sequencing and Fragment Analysis for the Detection and Allelic Ratio Determination of FLT3 Internal Tandem Duplication. Diagn Pathol 2022, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Chaudhary, P.; Ahmad, F.; Arora, N. Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Next-Generation Sequencing Panels for Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2024, 46, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobeck, A.D.; Wendt, S.; Krohn, S.; Knuebel, G.; Bartels, S.; Schipper, E.; Junghanss, C.; Murua Escobar, H. Comparative Analyses of Targeted Myeloid Cancer Next-Generation Sequencing Panel in Fresh Blood, Bone Marrow and FFPE Material. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenaux, P.; Haase, D.; Santini, V.; Sanz, G.F.; Platzbecker, U.; Mey, U.; Esmo Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo. org Myelodysplastic Syndromes: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up(Dagger☆). Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumniensuk, C.; Nobori, A.; Lee, T.; Senaratne, T.N.; Rao, D.; Pullarkat, S. Concordance of Peripheral Blood and Bone Marrow Next-Generation Sequencing in Hematologic Neoplasms. Adv Hematol 2022, 2022, 8091746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, F.; Michaels, P.D.; Wang, D.; Kim, A.S. Mutational Analysis of Hematologic Neoplasms in 164 Paired Peripheral Blood and Bone Marrow Samples by Next-Generation Sequencing. Blood Adv 2020, 4, 4362–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wu, J. NGS Panel Enhance Precise Diagnosis of Myeloid Neoplasms under WHO-HAEM5 and International Consensus Classification: An Observational Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e38556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.M.; Datto, M.; Duncavage, E.J.; Kulkarni, S.; Lindeman, N.I.; Roy, S.; Tsimberidou, A.M.; Vnencak-Jones, C.L.; Wolff, D.J.; Younes, A.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation and Reporting of Sequence Variants in Cancer: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and College of American Pathologists. J Mol Diagn 2017, 19, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.-M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating Morphologic, Clinical, and Genomic Data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, R.; Yeung, C.C.S. Advances in Next-Generation Sequencing and Emerging Technologies for Hematologic Malignancies. Haematologica 2024, 109, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, D.; Curigliano, G.; Riess, O.; Hofman, P.; Buttner, R.; Conte, P.; Cufer, T.; Gallagher, W.M.; Georges, N.; Kerr, K.; et al. Identifying the Steps Required to Effectively Implement Next-Generation Sequencing in Oncology at a National Level in Europe. J Pers Med 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlington, M.; Sujobert, P.; Kosmider, O.; Luque Paz, D.; Kaltenbach, S.; Figeac, M.; Hayette, S.; Mezaour, N.; Coquerelle, S.; Alary, A.S.; et al. Targeted High-Throughput Sequencing for Hematological Malignancies: A GBMHM Survey of Practice and Cost Evaluation in France. Hemasphere 2023, 7, e943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horak, P.; Griffith, M.; Danos, A.M.; Pitel, B.A.; Madhavan, S.; Liu, X.; Chow, C.; Williams, H.; Carmody, L.; Barrow-Laing, L.; et al. Standards for the Classification of Pathogenicity of Somatic Variants in Cancer (Oncogenicity): Joint Recommendations of Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen), Cancer Genomics Consortium (CGC), and Variant Interpretation for Cancer Consortium (VICC). Genetics in Medicine 2022, 24, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christinat, Y.; Hamelin, B.; Alborelli, I.; Angelino, P.; Barbié, V.; Bisig, B.; Dawson, H.; Frattini, M.; Grob, T.; Jochum, W.; et al. Reporting of Somatic Variants in Clinical Cancer Care: Recommendations of the Swiss Society of Molecular Pathology. Virchows Arch 2024, 485, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galimberti, S.; Balducci, S.; Guerrini, F.; Del Re, M.; Cacciola, R. Digital Droplet PCR in Hematologic Malignancies: A New Useful Molecular Tool. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindson, C.M.; Chevillet, J.R.; Briggs, H.A.; Gallichotte, E.N.; Ruf, I.K.; Hindson, B.J.; Vessella, R.L.; Tewari, M. Absolute Quantification by Droplet Digital PCR versus Analog Real-Time PCR. Nat Methods 2013, 10, 1003–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher, U.; Shumilov, E.; Flach, J.; Porret, N.; Joncourt, R.; Wiedemann, G.; Fiedler, M.; Novak, U.; Amstutz, U.; Pabst, T. Challenges in the Introduction of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for Diagnostics of Myeloid Malignancies into Clinical Routine Use. Blood Cancer J 2018, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuzzo, C.; Jovanovski, A.; Ali, M.S.; Cilloni, D.; Pergolizzi, B. Revealing the Mysteries of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: From Quantitative PCR through Next-Generation Sequencing and Systemic Metabolomic Profiling. JCM 2022, 11, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, S.; Waltersdorfer, M.; Loindl, S.; Moritz, J.M.; Herzog, S.A.; Bachmaier, G.; Berghold, A.; Kashofer, K.; Beham-Schmid, C.; Hoefler, G.; et al. Acute Myeloid Leukemia in the Next-Generation Sequencing Era: Real-World Data from an Austrian Tertiary Cancer Care Center. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rosa, S.E.A.; de Lima, L.B.; Silveira, C.N.; Cortes, L.G.F.; de Oliveira Filho, J.B.; de Souza Reis, R.; Cervato, M.C.; Rodrigues, P.H.S.; de Oliveira Pelegrino, K.; Petroni, R.C.; et al. Real-World Genomic Profiling of Acute Myeloid Leukemia and the Impact of European LeukemiaNet Risk Stratification 2022 Update. Clin Transl Oncol 2023, 25, 3431–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Le Beau, M.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Cazzola, M.; Vardiman, J.W. The 2016 Revision to the World Health Organization Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemia. Blood 2016, 127, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Qin, T.; Xu, Z.; Qu, S.; Pan, L.; Li, B.; Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; Yan, X.; et al. Comparison of the Revised 4th (2016) and 5th (2022) Editions of the World Health Organization Classification of Myelodysplastic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 2875–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.; Fontanillas, P.; Flannick, J.; Manning, A.; Grauman, P.V.; Mar, B.G.; Lindsley, R.C.; Mermel, C.H.; Burtt, N.; Chavez, A.; et al. Age-Related Clonal Hematopoiesis Associated with Adverse Outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, G.; Kähler, A.K.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lindberg, J.; Rose, S.A.; Bakhoum, S.F.; Chambert, K.; Mick, E.; Neale, B.M.; Fromer, M.; et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis and Blood-Cancer Risk Inferred from Blood DNA Sequence. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 2477–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeZern, A.E.; Malcovati, L.; Ebert, B.L. CHIP, CCUS, and Other Acronyms: Definition, Implications, and Impact on Practice. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Natarajan, P.; Silver, A.J.; Gibson, C.J.; Bick, A.G.; Shvartz, E.; McConkey, M.; Gupta, N.; Gabriel, S.; Ardissino, D.; et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuermans, A.; Honigberg, M.C. Clonal Haematopoiesis in Cardiovascular Disease: Prognostic Role and Novel Therapeutic Target. Nat Rev Cardiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Komrokji, R.; Al Ali, N.; Regelson, A.; Geyer, S.; Patel, A.; Saygin, C.; Zeidan, A.M.; Bewersdorf, J.P.; Mendez, L.; et al. Risk Prediction for Clonal Cytopenia: Multicenter Real-World Evidence. Blood 2024, 144, 2033–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.; Baer, C.; Hutter, S.; Wossidlo, N.; Hoermann, G.; Pohlkamp, C.; Walter, W.; Meggendorfer, M.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, T.; et al. Genomic Landscape of CCUS Compared to MDS and Its Implications on Risk Prediction. Leukemia 2024, 38, 1634–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcovati, L.; Gallì, A.; Travaglino, E.; Ambaglio, I.; Rizzo, E.; Molteni, E.; Elena, C.; Ferretti, V.V.; Catricalà, S.; Bono, E.; et al. Clinical Significance of Somatic Mutation in Unexplained Blood Cytopenia. Blood 2017, 129, 3371–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaemmanuil, E.; Cazzola, M.; Boultwood, J.; Malcovati, L.; Vyas, P.; Bowen, D.; Pellagatti, A.; Wainscoat, J.S.; Hellstrom-Lindberg, E.; Gambacorti-Passerini, C.; et al. Somatic SF3B1 Mutation in Myelodysplasia with Ring Sideroblasts. N Engl J Med 2011, 365, 1384–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcovati, L.; Papaemmanuil, E.; Bowen, D.T.; Boultwood, J.; Della Porta, M.G.; Pascutto, C.; Travaglino, E.; Groves, M.J.; Godfrey, A.L.; Ambaglio, I.; et al. Clinical Significance of SF3B1 Mutations in Myelodysplastic Syndromes and Myelodysplastic/Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Blood 2011, 118, 6239–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haferlach, T.; Nagata, Y.; Grossmann, V.; Okuno, Y.; Bacher, U.; Nagae, G.; Schnittger, S.; Sanada, M.; Kon, A.; Alpermann, T.; et al. Landscape of Genetic Lesions in 944 Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Leukemia 2014, 28, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Nannya, Y.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Devlin, S.M.; Tuechler, H.; Medina-Martinez, J.S.; Yoshizato, T.; Shiozawa, Y.; Saiki, R.; Malcovati, L.; et al. Implications of TP53 Allelic State for Genome Stability, Clinical Presentation and Outcomes in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, S.A.; Lee, L.A.; Seegmiller, A.C.; Mason, E.F. Diagnosis of TP53 -Mutated Myeloid Disease by the ICC and WHO Fifth Edition Classifications. Blood Advances 2025, 9, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejar, R.; Stevenson, K.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Galili, N.; Nilsson, B.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Kantarjian, H.; Raza, A.; Levine, R.L.; Neuberg, D.; et al. Clinical Effect of Point Mutations in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. N Engl J Med 2011, 364, 2496–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsley, R.C.; Mar, B.G.; Mazzola, E.; Grauman, P.V.; Shareef, S.; Allen, S.L.; Pigneux, A.; Wetzler, M.; Stuart, R.K.; Erba, H.P.; et al. Acute Myeloid Leukemia Ontogeny Is Defined by Distinct Somatic Mutations. Blood 2015, 125, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, H.; Visconte, V.; Sakaguchi, H.; Jankowska, A.M.; Abu Kar, S.; Jerez, A.; Przychodzen, B.; Bupathi, M.; Guinta, K.; Afable, M.G.; et al. Mutations in the Spliceosome Machinery, a Novel and Ubiquitous Pathway in Leukemogenesis. Blood 2012, 119, 3203–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconte, V.; O. Nakashima, M.; J. Rogers, H. Mutations in Splicing Factor Genes in Myeloid Malignancies: Significance and Impact on Clinical Features. Cancers 2019, 11, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschka, P.; Schlenk, R.F.; Gaidzik, V.I.; Herzig, J.K.; Aulitzky, T.; Bullinger, L.; Spath, D.; Teleanu, V.; Kundgen, A.; Kohne, C.-H.; et al. ASXL1 Mutations in Younger Adult Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Study by the German-Austrian Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group. Haematologica 2015, 100, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasik, S.; Middeke, J.M.; Kramer, M.; Röllig, C.; Krämer, A.; Scholl, S.; Hochhaus, A.; Crysandt, M.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Naumann, R.; et al. EZH2 Mutations and Impact on Clinical Outcome: An Analysis in 1,604 Patients with Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Haematologica 2020, 105, e228–e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramil, G.; Pratcorona, M.; Nomdedéu, J.F. Be Aware of the X: BCOR Mutations in Myeloid Neoplasms. haematol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, J.-N.; Stasik, S.; Röllig, C.; Sauer, T.; Scholl, S.; Hochhaus, A.; Crysandt, M.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Naumann, R.; Steffen, B.; et al. Alterations of Cohesin Complex Genes in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Differential Co-Mutations, Clinical Presentation and Impact on Outcome. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molica, M.; Perrone, S.; Mazzone, C.; Cesini, L.; Canichella, M.; de Fabritiis, P. CPX-351: An Old Scheme with a New Formulation in the Treatment of High-Risk AML. Cancers 2022, 14, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidzik, V.I.; Bullinger, L.; Schlenk, R.F.; Zimmermann, A.S.; Röck, J.; Paschka, P.; Corbacioglu, A.; Krauter, J.; Schlegelberger, B.; Ganser, A.; et al. RUNX1 Mutations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Results From a Comprehensive Genetic and Clinical Analysis From the AML Study Group. JCO 2011, 29, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taube, F.; Georgi, J.A.; Kramer, M.; Stasik, S.; Middeke, J.M.; Röllig, C.; Krug, U.; Krämer, A.; Scholl, S.; Hochhaus, A.; et al. CEBPA Mutations in 4708 Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Differential Impact of bZIP and TAD Mutations on Outcome. Blood 2022, 139, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Cai, Y.; Lai, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Clinical Features and Monitoring of Germline CEBPA -Mutated Carriers. Blood 2023, 142, 1366–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falini, B.; Sorcini, D.; Perriello, V.M.; Sportoletti, P. Functions of the Native NPM1 Protein and Its Leukemic Mutant. Leukemia 2025, 39, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falini, B.; Brunetti, L.; Sportoletti, P.; Martelli, M.P. NPM1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: From Bench to Bedside. Blood 2020, 136, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, G.C.; Aldoss, I.; Thirman, M.J.; DiPersio, J.; Arellano, M.; Blachly, J.S.; Mannis, G.N.; Perl, A.; Dickens, D.S.; McMahon, C.M.; et al. Menin Inhibition With Revumenib for KMT2A-Rearranged Relapsed or Refractory Acute Leukemia (AUGMENT-101). JCO 2025, 43, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dali, S.A.; Al-Mashdali, A.F.; Kalfah, A.; Mohamed, S.F. Menin Inhibitors in KMT2A-Rearranged and NPM1-Mutated Acute Leukemia: A Scoping Review of Safety and Efficacy. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2025, 213, 104783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arellano, M.L.; Thirman, M.J.; DiPersio, J.F.; Heiblig, M.; Stein, E.M.; Schuh, A.C.; Žučenka, A.; de Botton, S.; Grove, C.S.; Mannis, G.N.; et al. Menin Inhibition with Revumenib for NPM1-Mutated Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia: The AUGMENT-101 Study. Blood 2025, 146, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severina, N.; Sidorova, Y.; Risinskaya, N.; Biderman, B.; Pshenychnyy, A.; Ryzhikova, N.; Lukianova, I.; Kashlakova, A.; Sudarikov, A. PB1792: NGS VS PCR FOR THE DETECTION OF NPM1 GENE MUTATIONS IN ACUTE MYELOID LEUKEMIA. Hemasphere 2022, 6, 1672–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonk, C.M.; Grob, T.; Rijken, M.; Kavelaars, F.G.; Konijnenburg, J.M.L.; Ossenkoppele, G.J.; Manz, M.G.; Havelange, V.; Fløisand, Y.; Löwenberg, B.; et al. Advantages of a Genomic DNA-Based next-Generation Sequencing Assay for Detection of Mutant NPM1 Measurable Residual Disease in AML. Blood Adv 2025, 9, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluda, B.; Rodriguez-Veiga, R.; Sargas, C.; Ayala, R.; Larráyoz, M.J.; Chillón, M.C.; Soria-Saldise, E.; Bilbao, C.; Prados De La Torre, E.P.; Navarro, I.; et al. Conventional PCR Versus Next Generation Sequencing for Diagnosis of FLT3, IDH and NPM1 Mutations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Results of the PETHEMA PCR-LMA Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akabane, H. How Often Do Cytogenetics and NGS Information Impact Upfront Treatment in AML? Blood 2022, 140, 11607–11608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimony, S.; Stahl, M.; Stone, R.M. Acute Myeloid Leukemia: 2025 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-Stratification, and Management. American Journal of Hematology 2025, 100, 860–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research, C. for D.E. and FDA Approves Ivosidenib for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. FDA 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, R.M.; Mandrekar, S.J.; Sanford, B.L.; Laumann, K.; Geyer, S.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Thiede, C.; Prior, T.W.; Döhner, K.; Marcucci, G.; et al. Midostaurin plus Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia with a FLT3 Mutation. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erba, H.P.; Montesinos, P.; Kim, H.-J.; Patkowska, E.; Vrhovac, R.; Žák, P.; Wang, P.-N.; Mitov, T.; Hanyok, J.; Kamel, Y.M.; et al. Quizartinib plus Chemotherapy in Newly Diagnosed Patients with FLT3-Internal-Tandem-Duplication-Positive Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (QuANTUM-First): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1571–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesinos, P.; Recher, C.; Vives, S.; Zarzycka, E.; Wang, J.; Bertani, G.; Heuser, M.; Calado, R.T.; Schuh, A.C.; Yeh, S.-P.; et al. Ivosidenib and Azacitidine in IDH1-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petermichl, V.; Fuchs, S.; Weber, M.; Gobat, K.; Micheloud, C.; Graf, L.; Gerth, Y.; Goede, J.S.; Lehmann, T.; Driessen, C.; et al. Prognostic Impact of the AML60+ Score for Elderly Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treated with Hypomethylating Agents: A Retrospective Multicentric Analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bérard, E.; Röllig, C.; Bertoli, S.; Pigneux, A.; Tavitian, S.; Kramer, M.; Serve, H.; Bornhäuser, M.; Platzbecker, U.; Müller-Tidow, C.; et al. A Scoring System for AML Patients Aged 70 Years or Older, Eligible for Intensive Chemotherapy: A Study Based on a Large European Data Set Using the DATAML, SAL, and PETHEMA Registries. Blood Cancer J. 2022, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clichet, V.; Boyer, T. Artificial Intelligence-Based Myelodysplastic Syndromes Score, 2022 Classifications, and the Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System: A Perfect Match. haematol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; Estey, E.; Grimwade, D.; Amadori, S.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Büchner, T.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Larson, R.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of AML in Adults: 2017 ELN Recommendations from an International Expert Panel. Blood 2017, 129, 424–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Manero, G. Myelodysplastic Syndromes: 2023 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-Stratification, and Management. Am J Hematol 2023, 98, 1307–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, P.L.; Tuechler, H.; Schanz, J.; Sanz, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Solé, F.; Bennett, J.M.; Bowen, D.; Fenaux, P.; Dreyfus, F.; et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Blood 2012, 120, 2454–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voso, M.T.; Fenu, S.; Latagliata, R.; Buccisano, F.; Piciocchi, A.; Aloe-Spiriti, M.A.; Breccia, M.; Criscuolo, M.; Andriani, A.; Mancini, S.; et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) Predicts Survival and Leukemic Evolution of Myelodysplastic Syndromes Significantly Better Than IPSS and WHO Prognostic Scoring System: Validation by the Gruppo Romano Mielodisplasie Italian Regional Database. JCO 2013, 31, 2671–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Tuechler, H.; Greenberg, P.L.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Arango Ossa, J.E.; Nannya, Y.; Devlin, S.M.; Creignou, M.; Pinel, P.; Monnier, L.; et al. Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. NEJM Evidence 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Jonas, B.A.; Pullarkat, V.; Thirman, M.J.; Garcia, J.S.; Wei, A.H.; Konopleva, M.; Döhner, H.; Letai, A.; Fenaux, P.; et al. Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröger, N.; Bacigalupo, A.; Barbui, T.; Ditschkowski, M.; Gagelmann, N.; Griesshammer, M.; Gupta, V.; Hamad, N.; Harrison, C.; Hernandez-Boluda, J.C.; et al. Indication and Management of Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation in Myelofibrosis: Updated Recommendations by the EBMT/ELN International Working Group. The Lancet Haematology 2024, 11, e62–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenaux, P.; Gobbi, M.; Kropf, P.L.; Issa, J.-P.J.; Roboz, G.J.; Mayer, J.; Krauter, J.; Robak, T.; Kantarjian, H.; Novak, J.; et al. Guadecitabine vs Treatment Choice in Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Global Phase 3 Randomized Study. Blood Adv 2023, 7, 5027–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackmon, A.L.; Grunwald, M.R. Editorial: Molecular MRD Testing in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2025, 60, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahasrabudhe, K.D.; Mims, A.S. MRD in AML: Who, What, When, Where, and How? Blood 2024, 143, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, M.; Freeman, S.D.; Ossenkoppele, G.J.; Buccisano, F.; Hourigan, C.S.; Ngai, L.L.; Tettero, J.M.; Bachas, C.; Baer, C.; Béné, M.-C.; et al. 2021 Update on MRD in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Consensus Document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood 2021, 138, 2753–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivey, A.; Hills, R.K.; Simpson, M.A.; Jovanovic, J.V.; Gilkes, A.; Grech, A.; Patel, Y.; Bhudia, N.; Farah, H.; Mason, J.; et al. Assessment of Minimal Residual Disease in Standard-Risk AML. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 374, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höllein, A.; Meggendorfer, M.; Dicker, F.; Jeromin, S.; Nadarajah, N.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, C.; Haferlach, T. NPM1 Mutated AML Can Relapse with Wild-Type NPM1: Persistent Clonal Hematopoiesis Can Drive Relapse. Blood Adv 2018, 2, 3118–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocciardi, S.; Dolnik, A.; Kapp-Schwoerer, S.; Rücker, F.G.; Lux, S.; Blätte, T.J.; Skambraks, S.; Krönke, J.; Heidel, F.H.; Schnöder, T.M.; et al. Clonal Evolution Patterns in Acute Myeloid Leukemia with NPM1 Mutation. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, F.; Cardoso, R.; Chen, C.L.; Douglas, G.R.; Elloway, J.; Escobar, P.A.; Harper, T.; Heflich, R.H.; Kidd, D.; Lynch, A.M.; et al. Error-Corrected next Generation Sequencing – Promises and Challenges for Genotoxicity and Cancer Risk Assessment. Mutation Research - Reviews in Mutation Research 2023, 792, 108466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yu, F.; Lu, D.; Huang, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, B.; Shu, K.; Pu, D. Enhanced Error Suppression for Accurate Detection of Low-Frequency Variants. Electrophoresis 2025, 46, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer-Seibert, J.S.; Meyer, S.E. Genetic Heterogeneity and Clonal Evolution in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol 2021, 28, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuringa, J.J.; Bonifer, C. Dissecting Clonal Heterogeneity in AML. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 782–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C.M.; Ferng, T.; Canaani, J.; Wang, E.S.; Morrissette, J.J.D.; Eastburn, D.J.; Pellegrino, M.; Durruthy-Durruthy, R.; Watt, C.D.; Asthana, S.; et al. Clonal Selection with RAS Pathway Activation Mediates Secondary Clinical Resistance to Selective FLT3 Inhibition in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discovery 2019, 9, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, R.B. Perspective on Measurable Residual Disease Testing in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Leukemia 2024, 38, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, M.J.; Hamadani, M.; Logan, B.R.; Jones, R.J.; Singh, A.K.; Litzow, M.R.; Wingard, J.R.; Papadopoulos, E.B.; Perl, A.E.; Soiffer, R.J.; et al. Measurable Residual Disease and Posttransplantation Gilteritinib Maintenance for Patients with FLT3-ITD-Mutated AML. Blood 2025, 145, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Tang, J.-L.; Tien, F.-M.; Kuo, Y.-Y.; Wu, D.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Tseng, M.-H.; Peng, Y.-L.; Hou, M.-F.; Chuang, Y.-K.; et al. Clinical Implications of Sequential MRD Monitoring by NGS at 2 Time Points after Chemotherapy in Patients with AML. Blood Advances 2021, 5, 2456–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnittger, S.; Schoch, C.; Dugas, M.; Kern, W.; Staib, P.; Wuchter, C.; Löffler, H.; Sauerland, C.M.; Serve, H.; Büchner, T.; et al. Analysis of FLT3 Length Mutations in 1003 Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Correlation to Cytogenetics, FAB Subtype, and Prognosis in the AMLCG Study and Usefulness as a Marker for the Detection of Minimal Residual Disease. Blood 2002, 100, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thol, F.; Kölking, B.; Damm, F.; Reinhardt, K.; Klusmann, J.-H.; Reinhardt, D.; von Neuhoff, N.; Brugman, M.H.; Schlegelberger, B.; Suerbaum, S.; et al. Next-Generation Sequencing for Minimal Residual Disease Monitoring in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients with FLT3-ITD or NPM1 Mutations. Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer 2012, 51, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, M.J.; Hamadani, M.; Logan, B.; Jones, R.J.; Singh, A.K.; Litzow, M.; Wingard, J.R.; Papadopoulos, E.B.; Perl, A.E.; Soiffer, R.J.; et al. Gilteritinib as Post-Transplant Maintenance for AML With Internal Tandem Duplication Mutation of FLT3. JCO 2024, 42, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, L.W.; Gui, G.; Page, K.M.; Ravindra, N.; Wong, Z.C.; Andrew, G.; Mukherjee, D.; Zeger, S.L.; El Chaer, F.; Spellman, S.; et al. DNA Sequencing to Detect Residual Disease in Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia Prior to Hematopoietic Cell Transplant. JAMA 2023, 329, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P.; Lambert, J.; Bucci, M.; Deswarte, C.; Boudry, A.; Lambert, J.; Fenwarth, L.; Micol, J.-B.; Terré, C.; Celli-Lebras, K.; et al. Multi-Target Measurable Residual Disease Assessed by Error-Corrected Sequencing in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: An ALFA Study. Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godley, L.A.; Shimamura, A. Genetic Predisposition to Hematologic Malignancies: Management and Surveillance. Blood 2017, 130, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio-Machin, A.; Vulliamy, T.; Hug, N.; Walne, A.; Tawana, K.; Cardoso, S.; Ellison, A.; Pontikos, N.; Wang, J.; Tummala, H.; et al. The Complex Genetic Landscape of Familial MDS and AML Reveals Pathogenic Germline Variants. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, J.; Chaparro, L.; Manzanares, A.; Xicoy, B.; Zamora, L.; Sole, F.; Calvete, O. Beyond Myeloid Neoplasms Germline Guidelines: Validation of the Thresholds Criteria in the Search of Germline Predisposition Variants. eJHaem 2024, 5, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliakas, P.; Tesi, B.; Wartiovaara-Kautto, U.; Stray-Pedersen, A.; Friis, L.S.; Dybedal, I.; Hovland, R.; Jahnukainen, K.; Raaschou-Jensen, K.; Ljungman, P.; et al. Nordic Guidelines for Germline Predisposition to Myeloid Neoplasms in Adults: Recommendations for Genetic Diagnosis, Clinical Management and Follow-Up. HemaSphere 2019, 3, e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawana, K.; Brown, A.L.; Churpek, J.E. Integrating Germline Variant Assessment into Routine Clinical Practice for Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Acute Myeloid Leukaemia: Current Strategies and Challenges. Br J Haematol 2022, 196, 1293–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godley, L.A.; DiNardo, C.D.; Bolton, K. Germline Predisposition in Hematologic Malignancies: Testing, Management, and Implications. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2024, 44, e432218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, M.; Bernardi, S.; Gandolfi, L.; Zanaglio, C.; Morello, E.; Turra, A.; Zollner, T.; Gramegna, D.; Rambaldi, B.; Cattina, F.; et al. Case Report: Late Onset of Myelodysplastic Syndrome From Donor Progenitor Cells After Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Which Lessons Can We Draw From the Reported Case? Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 564521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Yamashita, T.; Suzuki, R.; Matsumoto, K.; Nishimori, H.; Takahashi, S.; Iwato, K.; Nakaseko, C.; Kondo, T.; Imada, K.; et al. Donor Cell-Derived Hematological Malignancy: A Survey by the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1742–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.J.; Kim, H.T.; Zhao, L.; Murdock, H.M.; Hambley, B.; Ogata, A.; Madero-Marroquin, R.; Wang, S.; Green, L.; Fleharty, M.; et al. Donor Clonal Hematopoiesis and Recipient Outcomes After Transplantation. JCO 2022, 40, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speight, B.; Hanson, H.; Turnbull, C.; Hardy, S.; Drummond, J.; Khorashad, J.; Wragg, C.; Page, P.; Parkin, N.W.; Rio-Machin, A.; et al. Germline Predisposition to Haematological Malignancies: Best Practice Consensus Guidelines from the UK Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG), CanGene-CanVar and the NHS England Haematological Oncology Working Group. Br J Haematol 2023, 201, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, C.R.; Shimamura, A. Predisposition to Myeloid Malignancies in Shwachman-Diamond Syndrome: Biological Insights and Clinical Advances. Blood 2023, 141, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, T.S. Management of Fanconi Anemia beyond Childhood. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2023, 2023, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, N.R.; Cahill, H.; Diamond, Y.; McCleary, K.; Kotecha, R.S.; Marshall, G.M.; Mateos, M.K. Down Syndrome-Associated Leukaemias: Current Evidence and Challenges. Ther Adv Hematol 2024, 15, 20406207241257901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molica, M.; Perrone, S. Molecular Targets for the Treatment of AML in the Forthcoming 5th World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours. Expert Review of Hematology 2022, 15, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliakas, P.; Tesi, B.; Cammenga, J.; Stray-Pedersen, A.; Jahnukainen, K.; Andersen, M.K.; Ågerstam, H.; Creignou, M.; Dybedal, I.; Raaschou-Jensen, K.; et al. How to Manage Patients with Germline DDX41 Variants: Recommendations from the Nordic Working Group on Germline Predisposition for Myeloid Neoplasms. HemaSphere 2024, 8, e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Ross, S.R. Multifunctional Role of DEAD-Box Helicase 41 in Innate Immunity, Hematopoiesis and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, H.; Saiki, R.; Nannya, Y.; Korotev, S.; Gurnari, C.; Takeda, J.; Momozawa, Y.; Best, S.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Yoshizato, T.; et al. Germ Line DDX41 Mutations Define a Unique Subtype of Myeloid Neoplasms. Blood 2023, 141, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Qin, T.; Xu, Z.; Jia, Y.; Qu, S.; Li, B.; Pan, L.; Gao, Q.; Jiao, M.; et al. Combination Therapy with Venetoclax and Azacitidine for the Treatment of Myelodysplastic Syndromes with DDX41 Mutations. Hematology 2024, 29, 2338509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanaa, A.; He, R.; Foran, J.M.; Badar, T.; Gangat, N.; Pardanani, A.; Hogan, W.J.; Litzow, M.R.; Patnaik, M.; Al-Kali, A.; et al. Venetoclax plus Hypomethylating Agents in DDX41-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukaemia and Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Mayo Clinic Series on 12 Patients. British Journal of Haematology 2024, 204, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, H.B.; Nanaa, A.; Viswanatha, D.; Foran, J.M.; Badar, T.; Sproat, L.; He, R.; Nguyen, P.; Jevremovic, D.; Salama, M.E.; et al. Genetic Features and Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Isolated and Comutated DDX41-Mutated Myeloid Neoplasms. Blood Adv 2022, 6, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; White, T.; Xie, W.; Cui, W.; Peker, D.; Zeng, G.; Wang, H.-Y.; Vagher, J.; Brown, S.; Williams, M.; et al. AML with Germline DDX41 Variants Is a Clinicopathologically Distinct Entity with an Indolent Clinical Course and Favorable Outcome. Leukemia 2022, 36, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanaa, A.; He, R.; Viswanatha, D.; Nguyen, P.; Jevremovic, D.; Foran, J.M.; Yi, C.A.; Greipp, P.T.; Gangat, N.; Patnaik, M.; et al. Comparison between GATA2 and DDX41-Mutated Myeloid Neoplasms. Leuk Res 2022, 121, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, Y.P.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.A.; Loghavi, S.; DiNardo, C.D.; Gerstein, Y.; Hu, S.; Tang, Z.; Ilagan, C.J.L.; Thakral, B.; et al. The Spectrum of Hematologic Neoplasms in Patients with Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. American J Hematol 2024, 99, 2416–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikarami, F.; Xie, H.M.; Riedel, S.S.; Goodrow, H.T.; Barrett, D.R.; Mahdavi, L.; Lenard, A.; Chen, C.; Yamauchi, T.; Danis, E.; et al. GATA2 Links Stemness to Chemotherapy Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2025, 145, 2179–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, K.R.; Hickstein, D.D. The Spectrum of GATA2 Deficiency Syndrome. Blood 2023, 141, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wlodarski, M.W.; Hirabayashi, S.; Pastor, V.; Starý, J.; Hasle, H.; Masetti, R.; Dworzak, M.; Schmugge, M.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.; Ussowicz, M.; et al. Prevalence, Clinical Characteristics, and Prognosis of GATA2-Related Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Children and Adolescents. Blood 2016, 127, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Petitto, G.; El Boghdadly, Z.; Nicolet, D.; Cooper, J.; Eisfeld, A.-K.; Klein, V.; Walker, M.C.; Mrózek, K.; Bezerra, E.; Brammer, J.E.; et al. GATA2-Mutated AML: Clinical Outcomes and Spectrum of Infections in Patients Undergoing or Not Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Blood 2024, 144, 7309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, M.; Liquori, A.; Such, E.; Zúñiga, Á.; Cervera, J. The Clinical Spectrum, Diagnosis, and Management of GATA2 Deficiency. Cancers 2023, 15, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruijn, M.; Dzierzak, E. Runx Transcription Factors in the Development and Function of the Definitive Hematopoietic System. Blood 2017, 129, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Deuitch, N.; Merguerian, M.; Cunningham, L.; Davis, J.; Bresciani, E.; Diemer, J.; Andrews, E.; Young, A.; Donovan, F.; et al. Genomic Landscape of Patients with Germline RUNX1 Variants and Familial Platelet Disorder with Myeloid Malignancy. Blood Adv 2024, 8, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif, P.A.; Konstandin, N.P.; Metzeler, K.H.; Herold, T.; Pasalic, Z.; Ksienzyk, B.; Dufour, A.; Schneider, F.; Schneider, S.; Kakadia, P.M.; et al. RUNX1 Mutations in Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia Are Associated with a Poor Prognosis and Up-Regulation of Lymphoid Genes. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, C.C.; Drazer, M.W.; Yu, K.; Lawrence, D.M.; Feng, J.; Arriola-Martinez, L.; Pozsgai, M.J.; McNeely, K.E.; Ha, T.; Venugopal, P.; et al. Somatic Mutational Landscape of Hereditary Hematopoietic Malignancies Caused by Germline Variants in RUNX1, GATA2, and DDX41. Blood Adv 2023, 7, 6092–6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noetzli, L.; Lo, R.W.; Lee-Sherick, A.B.; Callaghan, M.; Noris, P.; Savoia, A.; Rajpurkar, M.; Jones, K.; Gowan, K.; Balduini, C.L.; et al. Germline Mutations in ETV6 Are Associated with Thrombocytopenia, Red Cell Macrocytosis and Predisposition to Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Nat Genet 2015, 47, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Churpek, J.E.; Keel, S.B.; Walsh, T.; Lee, M.K.; Loeb, K.R.; Gulsuner, S.; Pritchard, C.C.; Sanchez-Bonilla, M.; Delrow, J.J.; et al. Germline ETV6 Mutations in Familial Thrombocytopenia and Hematologic Malignancy. Nat Genet 2015, 47, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noris, P.; Favier, R.; Alessi, M.-C.; Geddis, A.E.; Kunishima, S.; Heller, P.G.; Giordano, P.; Niederhoffer, K.Y.; Bussel, J.B.; Podda, G.M.; et al. ANKRD26-Related Thrombocytopenia and Myeloid Malignancies. Blood 2013, 122, 1987–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pippucci, T.; Savoia, A.; Perrotta, S.; Pujol-Moix, N.; Noris, P.; Castegnaro, G.; Pecci, A.; Gnan, C.; Punzo, F.; Marconi, C.; et al. Mutations in the 5’ UTR of ANKRD26, the Ankirin Repeat Domain 26 Gene, Cause an Autosomal-Dominant Form of Inherited Thrombocytopenia, THC2. Am J Hum Genet 2011, 88, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noris, P.; Perrotta, S.; Seri, M.; Pecci, A.; Gnan, C.; Loffredo, G.; Pujol-Moix, N.; Zecca, M.; Scognamiglio, F.; De Rocco, D.; et al. Mutations in ANKRD26 Are Responsible for a Frequent Form of Inherited Thrombocytopenia: Analysis of 78 Patients from 21 Families. Blood 2011, 117, 6673–6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenza, L.; Borelli, E.; Bigi, S.; Giusti, D.; Longo, G.; Odejide, O.; Porro, C.A.; Zimmermann, C.; Efficace, F.; Bruera, E.; et al. Early Palliative Care in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2022, 14, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.G.; Stein, A.; Fathi, A.T.; Pullarkat, V. Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory AML—Novel Treatment Options Including Immunotherapy. American Journal of Hematology 2025, 100, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molica, M.; Perrone, S.; Andriola, C.; Rossi, M. Immunotherapy with Monoclonal Antibodies for Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Work in Progress. Cancers 2023, 15, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, S.; Borsi, E.; Patuelli, A.; Bandini, L.; Mancini, M.; Forte, D.; Nanni, J.; Barone, M.; Grassi, A.; Cristiano, G.; et al. Tracking Response and Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia through Single-Cell DNA Sequencing Helps Uncover New Therapeutic Targets. IJMS 2024, 25, 10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, R.E.; Alfonso Pierola, A.; Kc, D.; Abaza, Y.M.; Abou Zahr, A.; Chamoun, K.; Montalban-Bravo, G.; Takahashi, K.; Jabbour, E.; Kadia, T.M.; et al. Impact of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) on Treatment Selection in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). JCO 2018, 36, 103–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay Banskota, S.; Khanal, N.; Bhatt, V.R. A Precision Medicine Approach to Management of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Older Adults. Current Opinion in Oncology 2020, 32, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snaith, O.; Poveda-Rogers, C.; Laczko, D.; Yang, G.; Morrissette, J.J.D. Cytogenetics and Genomics of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2024, 37, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Yu, H.; Ma, T.; Lei, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Yan, H.; Jiang, L.; Chen, B. The Application of Targeted RNA Sequencing for KMT2A-Partial Tandem Duplication Identification and Integrated Analysis of Molecular Characterization in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Mol Diagn 2021, 23, 1478–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawas, M.T.; Kosuri, S. Utility or Futility? A Contemporary Approach to Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for TP53-Mutated MDS/AML. Blood Advances 2024, 8, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Maiti, A.; Loghavi, S.; Pourebrahim, R.; Kadia, T.M.; Rausch, C.R.; Furudate, K.; Daver, N.G.; Alvarado, Y.; Ohanian, M.; et al. Outcomes of TP53-Mutant Acute Myeloid Leukemia with Decitabine and Venetoclax. Cancer 2021, 127, 3772–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimony, S.O.; Murdock, H.; Keating, J.; Reilly, C.R.; Tsai, H.K.; Gibson, C.J.; Faderl, S.; Wagner, T.; Dronamraju, N.; Lin, T.L.; et al. AML-MR Mutations Drive the Benefit of CPX-351 over 7+3 in the Pivotal Phase 3 AML Trial. Blood 2024, 144, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, T.; Nanaa, A.; Atallah, E.; Shallis, R.M.; Guilherme, S. de C.C.; Goldberg, A.D.; Saliba, A.N.; Patel, A.; Bewersdorf, J.P.; DuVall, A.S.; et al. Comparing Venetoclax in Combination with Hypomethylating Agents to Hypomethylating Agent-Based Therapies for Treatment Naive TP53-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Results from the Consortium on Myeloid Malignancies and Neoplastic Diseases (COMMAND). Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallman, D.A.; Stahl, M. TP53-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: How Can We Improve Outcomes? Blood 2025, 145, 2828–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassin, O.; Oren, M. Drugging P53 in Cancer: One Protein, Many Targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2023, 22, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, S.; Ottone, T.; Zhdanovskaya, N.; Molica, M. How Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Escapes from FMS-Related Tyrosine Kinase 3 (FLT3) Inhibitors? Still an Overrated Complication? Cancer Drug Resist 2023, 6, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Loghavi, S.; Daver, N.; Ravandi, F.; DiNardo, C.D.; Kadia, T.M.; Borthakur, G.; Jabbour, E.; Yilmaz, M.; Issa, G.C.; et al. Cytomolecular Mechanisms of Relapse and Post-Relapse Outcomes After Frontline FLT3 Inhibitor-Based Therapy in FLT3-Mutated AML. American Journal of Hematology n/a. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Takahashi, S.; Ouchi, K.; Otsuki, Y.; Wakayama, S.; Ishioka, C. Different Impacts of TP53 Mutations on Cell Cycle-Related Gene Expression among Cancer Types. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, N.; Ricker, C.; Messersmith, H.; Balmaña, J.; Domchek, S.; Stoffel, E.M.; Almhanna, K.; Arun, B.; Chavarri-Guerra, Y.; Cohen, S.A.; et al. Selection of Germline Genetic Testing Panels in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Guideline. JCO 2024, 42, 2599–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferlach, T.; Eckardt, J.-N.; Walter, W.; Maschek, S.; Kather, J.N.; Pohlkamp, C.; Middeke, J.M. AML Diagnostics in the 21st Century: Use of AI. Seminars in Hematology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Pu, X.; Hu, D.; Yang, M. Machine Learning-Based Biomarker Screening for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Prognosis and Therapy from Diverse Cell-Death Patterns. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 17874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Functional Category | Example Genes / Alterations | Consequences of Genetic Alteration |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Transduction | FLT3, NRAS, KRAS, c-KIT, PTPN11 | Confers proliferative advantages through the hyperactivation of signaling pathways like JAK/STAT, PI3K/AKT, and RAF/MEK/ERK. |

| Myeloid Transcription Factors | RUNX1, CEBPA, or fusions like RUNX1::RUNX1T1, PML::RARA, CBFB::MYH11 | Causes transcriptional deregulation, which impairs or blocks normal hematopoietic differentiation. |

| Tumor Suppressor Genes | TP53, WT1, PHF6 | Deregulates normal transcription and alters cell cycle checkpoints and responses to cellular stress, often leading to increased proliferation. |

| Spliceosome Complex | SRSF2, SF3B1, U2AF1, ZRSR2 | Alters the proper maturation of mRNA, causing events like intron retention or exon skipping, which can lead to dysfunctional proteins. |

| Multifunctional Protein | NPM1 | Nucleophosmin, causes the protein to be abnormally located in the cytoplasm, affecting ribosome biogenesis and the stability of tumor suppressors like p53. |

| Cohesin Complex | SMC1A, SMC3, STAG2, RAD21 | Affects chromosomal segregation and gene expression by altering chromatin accessibility, leading to increased proliferation and decreased differentiation. |

| DNA Methylation | DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1/2 | Leads to global changes in the epigenetic landscape by altering DNA methylation patterns, which affects gene expression. |

| Chromatin Modifiers | ASXL1, EZH2, or fusions involving KMT2A | Perturbs epigenetic homeostasis through aberrant histone modifications, leading to widespread changes in gene transcription. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).