Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

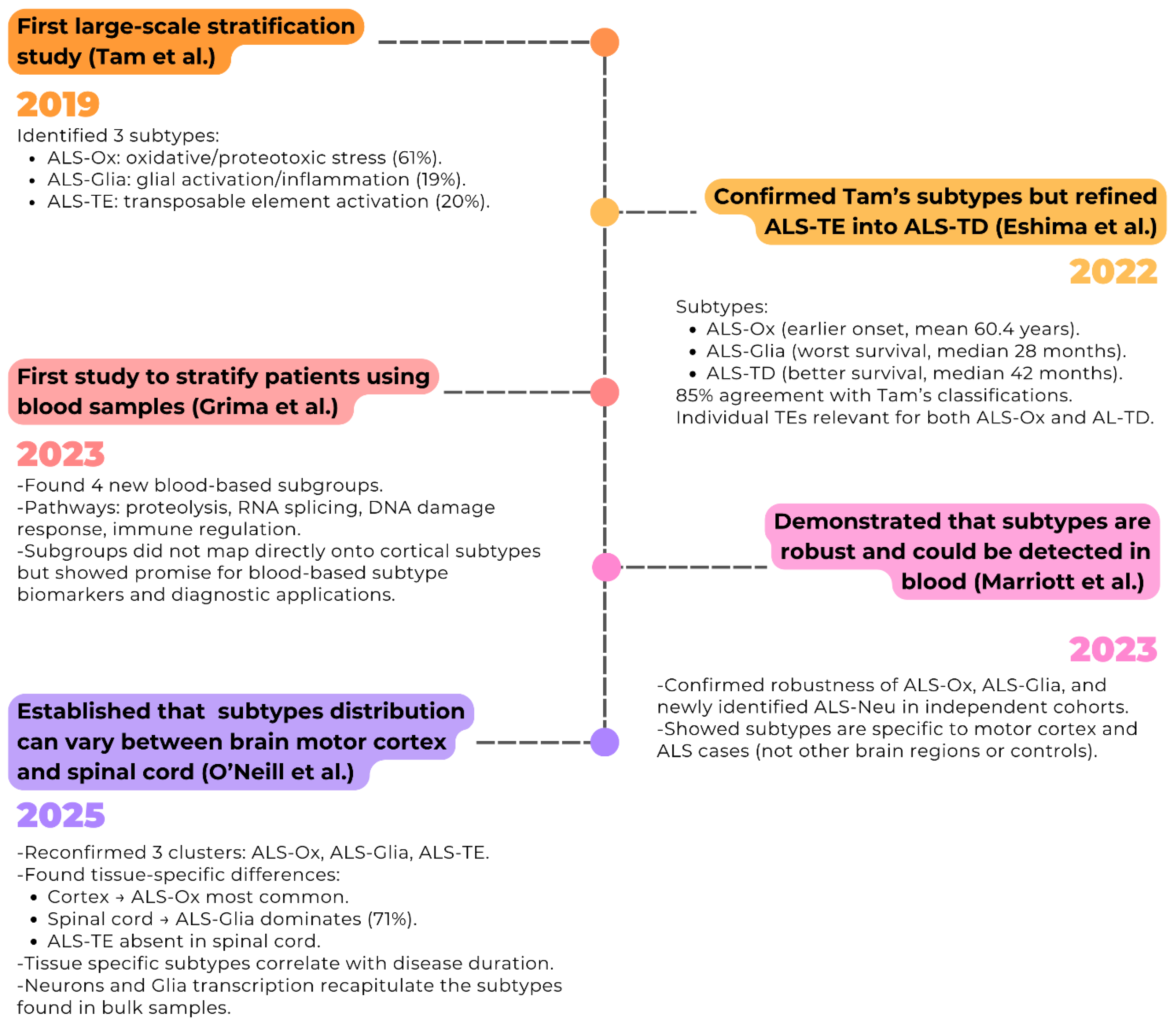

Chronology of Identification of ALS Molecular Subtype in the ALS Transcriptome

Brain Molecular Subtypes and Clinical Relevance

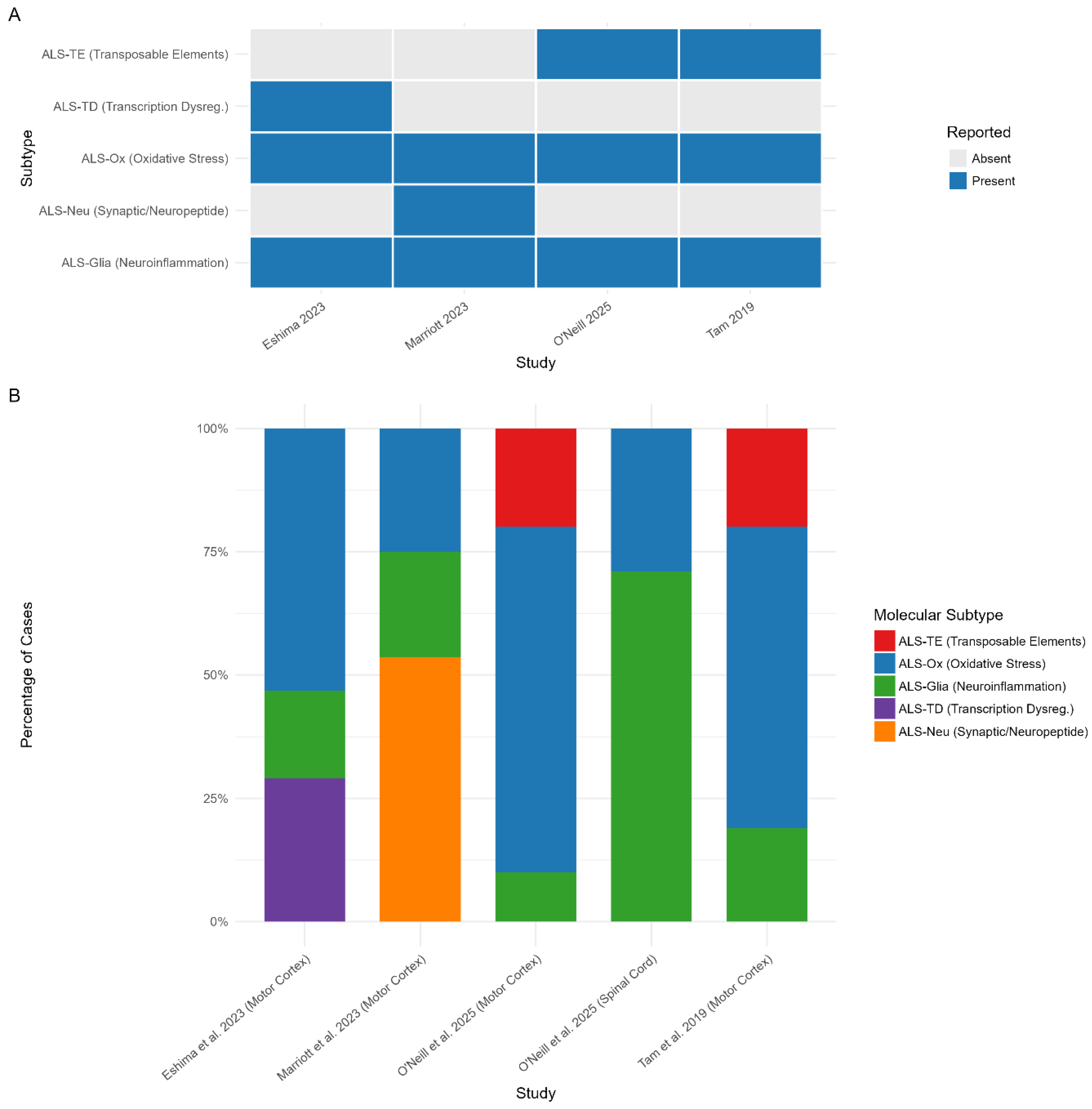

Consistency of the Molecular Subtypes Across Studies

ALS-TE: Increase in Transposable Element Expression Subtype

ALS-Ox: Oxidative Stress Subtype

ALS-Glia: Neuroinflammation/Glial Activation Subtype

ALS-TD: Transcription Dysregulation in ALS

ALS-Neu: Synaptic and Neuropeptide signalling Subtype

Tissue Specific Differences in Molecular Signatures

Biomarkers of Molecular Subtype

| Study | Tissue Type | Subtype | Cell Types | Proportion of pwALS | Replicated in Independent Samples | Tested on Pre-mortem Samples | Molecular characteristics | Clinical Feature Correlation | Code and Data Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tam, et al., 2019 | Frontal and motor cortex tissue |

Increased Transposable element expression (ALS-TE) |

n/a | 20% | Yes | No | ↑ Retrotransposon activation ↑ TDP-43 dysfunction ↑ Transposable elements ↓ Spliceosome components ↓ Protein export pathways |

Associated with limb onset (56% of patients) No survival differences or significant correlations |

Data: All data is provided by the Gene Expression Omnibus database: Motor cortex RNA-seq datasets from CSHL motor cortex: Accession Numbers: GSE122649 CLIP-seq and RNA-seq datasets from SH-SY5Y cells: Accession Numbers: GSE122650 RNA-seq datasets provided by the NYGC ALS Consortium: Accession Numbers: GSE124439 Code is unavailable |

|

Oxidative stress (ALS-Ox) |

n/a | 61% | Yes | No | ↑ Oxidative stress markers ↑ Proteotoxic stress ↑ Autophagy pathways ↑ Oxidative phosphorylation |

No survival differences or significant correlations | |||

|

Glial markers (ALS-Glia) |

- Astrocytes (markers) - Microglia (markers) Oligodendrocytes (markers) |

19% | Yes | No | ↑ Glial activation markers ↑Neuroinflammation |

No survival differences or significant correlations | |||

| Eshima, et al., 2022 | Frontal and motor cortex tissue |

Dysregulation in Transcription (ALS-TD) |

n/a | 29.1% | No | No | ↑ Transcriptional dysregulation ↑ Pseudogenes ↑ lncRNAs, miRNAs ↑ Nonsense-mediated decay |

Better prognosis Median survival: 42 months Mean age of Onset: (62.7 ± 1.68 years) |

Data: Raw data from NCBI Run Selector: Accession code: PRJNA644618 The RSEM processed gene count matrix from Gene Expression Omnibus: Accession code: GSE153960 Processed RNA-seq count files: https://figshare.com/authors/Jarrett_Eshima/13813720 Code: Code for the analysis available in the Barbara Smith Lab GitHub repository: https://github.com/BSmithLab/ALSPatientStratification Scripts used for supervised Classification: https://github.com/plaisier-lab/U5_hNSC_Neural_G0 Classification models are unavailable. |

|

Oxidative stress (ALS-Ox) |

Cell Deconvolution analysis: - Excitatory neurons - Inhibitory neurons |

53.2% | No | No | ↑ Oxidative stress ↓ Oxidative phosphorylation ↑ Proteotoxic stress ↑ Synaptic alterations |

Intermediate survival: 36 months Mean age of Onset: (60.4 ± 1.16 years) |

|||

|

Glial markers (ALS-Glia) |

Cell Deconvolution analysis: - Microglial - Glial progenitor - Vascular cell - Inhibitory neurons |

17.7% | No | No | ↑ Glial activation ↑ Neuroinflammation ↑ MHC Class II ↑ Complement cascade ↓ Transposable elements |

Worse prognosis Median survival: 28 months Mean age of Onset: (63.2 ± 1.83 years) |

|||

| Grima, et al., 2023 | Peripheral blood tissue | Cluster 0 | n/a | 44% | No | n/a | ↑ Translation & Adaptive immune response ↓ Inflammatory / Innate immune response |

n/a |

Data: Raw Fastq files, raw gene counts and offset matrix are available at NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus: Accession code: GSE234297 Code: Code for the analysis is available in the Gitlab repository: https://gitlab.com/mq-mnd/grp_williams/sals_blood_rnaseq |

| Cluster 1 | n/a | ~10.5% | No | n/a |

↓ Proteolysis, Metabolic and RNA-splicing pathways |

n/a | |||

| Cluster 2 | n/a | ~10.5% | No | n/a | ↑ Proteolysis, Metabolic and RNA-splicing pathways (opposite to Cluster 1) | n/a | |||

| Cluster 3 | n/a | 35% | No | n/a | Intermediate profile between Clusters 1 and 2 with few unique genes | n/a | |||

| Marriott, et al., 2023 | Frontal and motor cortex tissue |

Synaptic and neuropeptide signalling (ALS-Neu) |

Cell Deconvolution analysis: - Motor Neurons |

53.6% | Yes | No | ↑ Synaptic signalling ↑ Neuropeptide activity ↑ Mitochondrial ATP synthesis ↑ cAMP signalling ↑ Neuroactive ligand binding |

Youngest mean age of onset: (58.8 ± 11.6) Disease duration in years (median(IQR)): 3.16 (1.96) |

Data: The RNA- seq validation set generated by Zucca et al. [38] can be found via the NCBI Sequence Read Archive: Accession numbers: PRJNA416880 PRJNA474387 The gene expression microarray data generated by Van Rheenan [37] are available via the Gene Expression Omnibus database: Accession number: GSE112681 The KCL Brain Bank data is available upon reasonable request. Target ALS dataset is available upon approval by the TargetALS Post-mortem Tissue Core. Code: The code used for the analyses performed: https://github.com/KHP-Informatics/HierarchicalClusteringALS/ Class Assignment models are available to use via the link: https://alsgeclustering.er.kcl.ac.uk |

|

Oxidative stress and apoptosis (ALS-Ox) |

Cell Deconvolution analysis: - Astrocytes - Endothelial cells |

25% | Yes | No | ↑ Oxidative stress ↑ Apoptosis signalling ↑ Muscle contraction ↑ Anti-inflammatory processes ↑ Metalloproteinase activity |

Oldest mean age of onset: (65.7 ± 12.3) Disease duration in years (median(IQR)): 2.30 (1.81) |

|||

|

Neuroinflammation (ALS-Glia) |

Cell Deconvolution analysis: - Microglial - Oligodendrocytes |

21.4% | Yes | No | ↑ Neuroinflammation ↑ MHC class II complex ↑ Complement cascade ↑ Interferon signalling ↑ M1 activated microglia |

Mean age of onset: (61.7 ± 15.7) Disease duration in years (median(IQR)): 2.38 (1.75) No significant correlations |

|||

| O’Neill, et al., 2025 | Frontal and motor cortex tissue |

Increased Transposable element expression (ALS-TE) |

Single cell Composition: - L5ET Neurons (TDP-43 dysfunction) - Excitatory neurons - Inhibitory neurons |

20% | No | No | ↑ TDP-43 pathology L5ET Neurons ↑Transposable elements expression in L5ET Neurons ↑ TDP-43 splicing defects |

↓Disease duration against Eigengene score (r=-0.25, P<0.05) |

Data: The RNA- seq and snRNA- seq data are available via the Gene Expression Omnibus: Accession Numbers: GSE271156 Post-mortem frontal/motor cortex and spinal cord RNA- seq was provided by the NYGC ALS Consortium: Accession Numbers: GSE137810 Code: The software developed that can quantify transposable elements from single-cell and single-nuclei datasets: https://github.com/mhammell-laboratory/CellRangerTE Class Assignment DANCer model is available via the study’s GitHub link: https://github.com/mhammell-laboratory/DANcer |

|

Oxidative stress (ALS-Ox) |

Single cell Composition: - L5ET Neurons |

70% | No | No | ↑Oxidative stress ↑Mitochondrial dysfunction |

No significant correlations | |||

|

Glial markers (ALS-Glia) |

Single cell Composition: - L5ET Neurons - Microglial |

10% | No | No | ↑Neuroinflammation ↑Microglial activation |

No significant correlations | |||

| Spinal Cord |

Oxidative stress (ALS-Ox) |

n/a | 29% | No | No | ↑Oxidative stress ↑Neuroactive ligands |

↓ Disease duration against Eigengene score (r=-0.29, P<3e-5) |

||

|

Glial markers (ALS-Glia) |

- Astrocytes (markers) - Microglia (markers) |

71% | No | No | ↑Inflammatory signatures ↑ TDP-43 dysfunction |

↓Disease duration against Eigengene score (r=-0.35, P<2e-10) |

Discussion and Future Directions

Funding

References

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçimen, F.; Lopez, E.R.; Landers, J.E.; Nath, A.; Chiò, A.; Chia, R.; Traynor, B.J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: translating genetic discoveries into therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chio, A.; Corr, E.M.; Logroscino, G.; Robberecht, W.; Shaw, P.J.; Simmons, Z.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2017, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, S.; Goizet, C.; Soulages, A.; Vallat, J.-M.; Le Masson, G. Genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A review. J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 399, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacoangeli, A.; Al Khleifat, A.; Sproviero, W.; Shatunov, A.; Jones, A.R.; Opie-Martin, S.; Naselli, E.; Topp, S.D.; Fogh, I.; Hodges, A.; et al. ALSgeneScanner: a pipeline for the analysis and interpretation of DNA sequencing data of ALS patients. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2019, 20, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacoangeli, A.; Lin, T.; Al Khleifat, A.; Jones, A.R.; Opie-Martin, S.; Coleman, J.R.; Shatunov, A.; Sproviero, W.; Williams, K.L.; Garton, F.; et al. Genome-wide Meta-analysis Finds the ACSL5-ZDHHC6 Locus Is Associated with ALS and Links Weight Loss to the Disease Genetics. Cell Rep. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rheenen, W.; van der Spek, R.A.A.; Bakker, M.K.; van Vugt, J.J.F.A.; Hop, P.J.; Zwamborn, R.A.J.; de Klein, N.; Westra, H.-J.; Bakker, O.B.; Deelen, P.; et al. Common and rare variant association analyses in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identify 15 risk loci with distinct genetic architectures and neuron-specific biology. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1636–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoangeli, A.; A Dilliott, A.; Al Khleifat, A.; Andersen, P.M.; A Başak, N.; Cooper-Knock, J.; Couratier, P.; Decarvalho, M.; E Drory, V.; Glass, J.D.; et al. Oligogenic structure of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis has genetic testing, counselling and therapeutic implications. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.R.; Iacoangeli, A.; Opie-Martin, S.; A van Vugt, J.J.F.; Al Khleifat, A.; Bredin, A.; Ossher, L.; Andersen, P.M.; Hardiman, O.; Mehta, A.R.; et al. The impact of age on genetic testing decisions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2022, 145, 4440–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshima, J.; O’Connor, S.A.; Marschall, E.; Bowser, R.; Plaisier, C.L.; Smith, B.S. Molecular subtypes of ALS are associated with differences in patient prognosis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriott, H.; Kabiljo, R.; Hunt, G.P.; Khleifat, A.A.; Jones, A.; Troakes, C.; Pfaff, A.L.; Quinn, J.P.; Koks, S.; Dobson, R.J.; Schwab, P.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Iacoangeli, A. Unsupervised machine learning identifies distinct ALS molecular subtypes in post-mortem motor cortex and blood expression data. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’nEill, K.; Shaw, R.; Bolger, I.; Tam, O.H.; Phatnani, H.; Hammell, M.G. ALS molecular subtypes are a combination of cellular and pathological features learned by deep multiomics classifiers. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, O.H.; Rozhkov, N.V.; Shaw, R.; Kim, D.; Hubbard, I.; Fennessey, S.; Propp, N.; Phatnani, H.; Kwan, J.; Sareen, D.; et al. Postmortem Cortex Samples Identify Distinct Molecular Subtypes of ALS: Retrotransposon Activation, Oxidative Stress, and Activated Glia. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 1164–1177.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, N.; Liu, S.; Southwood, D.; Henden, L.; Smith, A.; Lee, A.; Rowe, D.B.; D’SIlva, S.; Blair, I.P.; Williams, K.L. RNA sequencing of peripheral blood in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis reveals distinct molecular subtypes: Considerations for biomarker discovery. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2023, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacoangeli, A.; Fogh, I.; Selvackadunco, S.; Topp, S.D.; Shatunov, A.; van Rheenen, W.; Al-Khleifat, A.; Opie-Martin, S.; Ratti, A.; Calvo, A.; et al. SCFD1 expression quantitative trait loci in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are differentially expressed. Brain Commun. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.R.; Iacoangeli, A.; Adey, B.N.; Bowles, H.; Shatunov, A.; Troakes, C.; Garson, J.A.; McCormick, A.L.; Al-Chalabi, A. A HML6 endogenous retrovirus on chromosome 3 is upregulated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis motor cortex. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, H.; Garcon, G.; Patin, F.; Veyrat-Durebex, C.; Boyer, J.; Devos, D.; Vourc’h, P.; Andres, C.R.; Corcia, P. Panel of Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Biomarkers in ALS: A Pilot Study. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 2016, 44, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wen, J.; Liu, J.; Li, L. The roles of free radicals in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: reactive oxygen species and elevated oxidation of protein, DNA, and membrane phospholipids. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 2318–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calma, A.D.; Pavey, N.; Menon, P.; Vucic, S. Neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: pathogenic insights and therapeutic implications. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2024, 37, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geloso, M.C.; Corvino, V.; Marchese, E.; Serrano, A.; Michetti, F.; D’aMbrosi, N. The dual role of microglia in ALS: Mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.C.; Scotter, E.L. Transcriptional targets of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia protein TDP-43 – meta-analysis and interactive graphical database. Dis. Model. Mech. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, S.; Kitaoka, Y.; Kawata, S.; Nishiura, A.; Uchihashi, T.; Hiraoka, S.-I.; Yokota, Y.; Isomura, E.T.; Kogo, M.; Tanaka, S. Characteristics of Sensory Neuron Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Potential for ALS Therapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccaro, E.; Piol, D.; Basso, M.; Pennuto, M. Motor Neuron Diseases and Neuroprotective Peptides: A Closer Look to Neurons. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prudencio, M.; Gonzales, P.K.; Cook, C.N.; Gendron, T.F.; Daughrity, L.M.; Song, Y.; Ebbert, M.T.; van Blitterswijk, M.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Jansen-West, K.; et al. Repetitive element transcripts are elevated in the brain of C9orf72 ALS/FTLD patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 3421–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdebenito-Maturana, B.; Arancibia, E.; Riadi, G.; Tapia, J.C.; Carrasco, M. Locus-specific analysis of Transposable Elements during the progression of ALS in the SOD1G93A mouse model. PLOS ONE 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westarp, M.E.; Ferrante, P.; Perron, H.; Bartmann, P.; Kornhuber, H.H. Sporadic ALS/MND: a global neurodegeneration with retroviral involvement? J. Neurol. Sci. 1995, 129, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, P.; Westarp, M.; Mancuso, R.; Puricelli, S.; Westarp, M.; Mini, M.; Caputo, D.; Zuffolato, M. HTLV tax-rex DNA and antibodies in idiopathic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995, 129, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westarp, M.; Bartmann, P.; Rossler, J.; Geiger, E.; Westphal, K.P.; Schreiber, H.; Fuchs, D.; Westerp, M.P.; Kornhuber, H.H. Antiretroviral therapy in sporadic adult amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. NeuroReport 1993, 4, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, W.; Tuke, P.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Gaudin, P.; Ijaz, S.; Parton, M.; Garson, J. Detection of reverse transcriptase activity in the serum of patients with motor neurone disease. J. Med Virol. 2000, 61, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douville, R.; Liu, J.; Rothstein, J.; Nath, A. Identification of active loci of a human endogenous retrovirus in neurons of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 69, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.; Rowe, D.B.; Kiernan, M.C.; Vucic, S.; Mathers, S.; van Eijk, R.P.A.; Nath, A.; Montojo, M.G.; Norato, G.; Santamaria, U.A.; et al. Safety and tolerability of Triumeq in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the Lighthouse trial. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2019, 20, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, A.L.; Schumann, G.G.; Breen, G.; Bubb, V.J.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Quinn, J.P. Retrotransposons in the development and progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018, 90, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S.; Saxena, S.; Sierra-Delgado, J.A. Microglia in ALS: Insights into Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Cells 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensimon, G.; Leigh, P.N.; Tree, T.; Malaspina, A.; Payan, C.A.; Pham, H.-P.; Klaassen, P.; Shaw, P.J.; Al Khleifat, A.; Amador, M.D.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose IL-2 as an add-on therapy to riluzole (MIROCALS): a phase 2b, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2025, 405, 1837–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camu, W.; Mickunas, M.; Veyrune, J.-L.; Payan, C.; Garlanda, C.; Locati, M.; Juntas-Morales, R.; Pageot, N.; Malaspina, A.; Andreasson, U.; et al. Repeated 5-day cycles of low dose aldesleukin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (IMODALS): A phase 2a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. EBioMedicine 2020, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanese, A.; Rajkumar, S.; Sommer, D.; Masrori, P.; Hersmus, N.; Van Damme, P.; Witzel, S.; Ludolph, A.; Ho, R.; Boeckers, T.M.; et al. Multiomics and machine-learning identify novel transcriptional and mutational signatures in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2023, 146, 3770–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rheenen, W.; Diekstra, F.P.; Harschnitz, O.; Westeneng, H.-J.; Van Eijk, K.R.; Saris, C.G.J.; Groen, E.J.N.; A Van Es, M.; Blauw, H.M.; Van Vught, P.W.J.; et al. Whole blood transcriptome analysis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A biomarker study. PLOS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, S.; Gagliardi, S.; Pandini, C.; Diamanti, L.; Bordoni, M.; Sproviero, D.; Arigoni, M.; Olivero, M.; Pansarasa, O.; Ceroni, M.; et al. RNA-Seq profiling in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and controls. Sci. Data 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdebenito-Maturana, B.; Rojas-Tapia, M.I.; Carrasco, M.; Tapia, J.C. Dysregulated Expression of Transposable Elements in TDP-43M337V Human Motor Neurons That Recapitulate Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prudencio, M.; Humphrey, J.; Pickles, S.; Brown, A.-L.; Hill, S.E.; Kachergus, J.M.; Shi, J.; Heckman, M.G.; Spiegel, M.R.; Cook, C.; et al. Truncated stathmin-2 is a marker of TDP-43 pathology in frontotemporal dementia. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 6080–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakral, S.; Purohit, P.; Mishra, R.; Gupta, V.; Setia, P. The impact of RNA stability and degradation in different tissues to the determination of post-mortem interval: A systematic review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Belyadi and A. Haghighat, “Chapter 3 - Machine learning workflows and types,” in Machine Learning Guide for Oil and Gas Using Python, Gulf Professional Publishing, 2021, pp. 97-123.

- Guo, Y.-T.; Li, Q.-Q.; Liang, C.-S. The rise of nonnegative matrix factorization: Algorithms and applications. Inf. Syst. 2024, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, P. Tamayo, V. K. Mootha, S. Mukherjee, B. L. Ebert, M. A. Gillette, A. Paulovich, S. L. Pomeroy, T. R. Golub, E. S. Lander and J. P. Mesirov, “Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles,” 2005.

- Mathur, R.; Rotroff, D.; Ma, J.; Shojaie, A.; Motsinger-Reif, A. Gene set analysis methods: a systematic comparison. BioData Min. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiani, A.; Martinelli, I.; Bello, L.; Querin, G.; Puthenparampil, M.; Ruggero, S.; Toffanin, E.; Cagnin, A.; Briani, C.; Pegoraro, E.; Soraru, G. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Neurofilament light chain levels in definite subtypes of disease. JAMA Neurolog 2017, 74, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiman-Patterson, T.D.; Sher, R.B.; Blankenhorn, E.A.; Alexander, G.; Deitch, J.S.; Kunst, C.B.; Maragakis, N.; Cox, G. Effect of genetic background on phenotype variability in transgenic mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A window of opportunity in the search for genetic modifiers. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2011, 12, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venneti, S.; Robinson, J.L.; Roy, S.; White, M.T.; Baccon, J.; Xie, S.X.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Simulated brain biopsy for diagnosing neurodegeneration using autopsy-confirmed cases. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 122, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.; Nowak, A.; Zhang, S.; Moll, T.; Weimer, A.K.; Barcons, A.M.; Souza, C.D.S.; Ferraiuolo, L.; Kenna, K.; Zaitlen, N.; et al. Evaluation of a biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis derived from a hypomethylated DNA signature of human motor neurons. BMC Med Genom. 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.C.; Hänzelmann, S.; Hausmann, F.; Khatri, R.; Oller, S.; Parvaz, M.; Tzeplaeff, L.; Pasetto, L.; Gebelin, M.; Ebbing, M.; et al. Multiomic ALS signatures highlight subclusters and sex differences suggesting the MAPK pathway as therapeutic target. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bild and P. George Febbo, “Application of a priori established gene sets to discover biologically important differential expression in microarray data,” 2005.

- Khatri, P.; Sirota, M.; Butte, A.J. Ten years of pathway analysis: Current approaches and outstanding challenges. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Agosta, F. Does neuroinflammation sustain neurodegeneration in ALS? Neurology 2016, 87, 2508–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.; Lee, S.; Jeon, Y.-M.; Kim, S.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, H.-J. The role of TDP-43 propagation in neurodegenerative diseases: integrating insights from clinical and experimental studies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakowski, S.A.; Schuyler, A.D.; Feldman, E.L. Insulin-like growth factor-I for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2009, 10, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lyashchenko, A.K.; Lu, L.; Nasrabady, S.E.; Elmaleh, M.; Mendelsohn, M.; Nemes, A.; Tapia, J.C.; Mentis, G.Z.; Shneider, N.A. ALS-associated mutant FUS induces selective motor neuron degeneration through toxic gain of function. Nature Communications 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandoorne, T.; Veys, K.; Guo, W.; Sicart, A.; Vints, K.; Swijsen, A.; Moisse, M.; Eelen, G.; Gounko, N.V.; Fumagalli, L.; Fazal, R.; Germeys, C.; Quaegebeur, A.; Fendt, S.M.; Carmeliet, P.; Verfaillie, C.; Van Damme, P.; Ghesquière, B.; De Bock, K.; Van Den Bosch, L. Differentiation but not ALS mutations in FUS rewires motor neuron metabolism. Nature Communications 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, C.A.; Neale, B.M.; Heskes, T.; Posthuma, D. The statistical properties of gene-set analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Endogenous retroviruses in ALS: A reawakening? Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. A. Garson, L. Usher, A. Al-Chalabi, J. Huggett, E. F. Day and A. L. McCormick, “Quantitative analysis of human endogenous retrovirus-K transcripts in postmortem premotor cortex fails to confirm elevated expression of HERV-K RNA in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” Acta neuropathologica communications, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 45, 3 2019. [CrossRef]

- McCormick, A.L.; Brown, R.H.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Garson, J.A. Quantification of reverse transcriptase in ALS and elimination of a novel retroviral candidate. Neurology 2008, 70, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, A.J.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Ferrante, K.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Brown, R.H.; Garson, J.A. Detection of serum reverse transcriptase activity in patients with ALS and unaffected blood relatives. Neurology 2005, 64, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. A. Garson, L. Usher, A. Al-Chalabi, J. Huggett, E. F. Day and A. L. McCormick, “Quantitative analysis of human endogenous retrovirus-K transcripts in postmortem premotor cortex fails to confirm elevated expression of HERV-K RNA in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” Acta neuropathologica communications, vol. 7, no. 102, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).