1. Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal degenerative disorder in brain that progresses with age [

1,

2], resulted from the mutation in the huntingtin (HTT) gene in chromosome 4p16.3, where an expansion of CAG trinucleotide repeats (more than 35 CAG) in exon1 of the HTT gene onsets the disease by expressing a toxic HTT protein having expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) amino acids [1-3]. The symptoms of HD can be characterized by a triad of progressive motor, cognitive, and psychiatric/behavioral disturbances [

1,

4], and are typically categorized into three stages, which are presymptomatic, prodromal, and manifest [

5]. The presymptomatic stage is a prolonged stage during which individuals do not demonstrate any indications or symptoms regarding HD despite having expanded CAG trinucleotide mutations [

5]. Perhaps, individuals with HD often maintain a typical lifestyle, similar to those without HD, until the onset of the prodromal stage, where individuals with expanded CAG begin to exhibit unspecified or potential motor impairments upon examination and minor but notable cognitive alterations [

5]. In the manifest stage, individuals display the triad symptoms of HD, including progressive motor, cognitive, and psychiatric/behavioral alterations [

5].

HD is diagnosed based on confirmed motor, cognitive, and behavioral signs and symptoms [

6]. These signs and symptoms, specifically, the motor function of HD, are most widely assessed using the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS), which is based on the diagnostic confidence level (DCL) [

6]. The DCL value varies from 1 to 4, where a DCL value of 4 indicates 99% confidence that the motor impairments are due to HD [

6]. However, a DCL score of 4 reflects the advanced stage of the disease, indicating that by that time the disease has already progressed to the advanced stage [

6]. Hence, detecting any early abnormalities and diagnosing HD during the prolonged presymptomatic stage utilizing DCL score is insufficient [

6], as during this stage, individuals do not demonstrate any of the triad of HD symptoms, which would appear as notable clinical signs after decades [

5]. Thus, owing to the prolonged duration of the presymptomatic stage [

5], clinical staging standards could fail to identify any subtle changes during this stage, highlighting the need for a robust and efficient way to monitor the disease onset as well as the progression and stage of the disease.

Recent research has focused on developing an efficient HD staging approach that could precisely diagnose HD from birth until the medical diagnosis [

6]. In 2022, Tabrizi et al. proposed an alternative HD diagnosis system, the Huntington’s Disease Integrated Staging System (HD-ISS), which harnesses biomarkers, besides HD pathophysiology for HD staging [

6]. In brief, the HD-ISS systems consist of four stages, 0 to 3, where individuals with stage 0 carry the HTT mutation, but no detectable clinical symptoms [

6]. Individuals in stage 1 possess early pathological alterations, whereas stage 2 represents a clinical phenotype, and functional deterioration is associated with stage 3 [

6]. However, owing to the stringent landmark assessment criteria of the HD-ISS system, which categorizes HD stages by assessing a measure in at least 100 cohorts, no HD biomarkers have been identified till now [

6]. This makes it indispensable to develop novel biomarkers that may satisfy the HD-ISS system. Moreover, developing a prognostic biomarker offers not only a way of diagnosing HD during the presymptomatic stage but also an approach to monitor the disease progression, allowing individuals to take necessary actions to prevent and/or slow down the manifestation of HD [

7]. They can also be utilized to monitor the efficacy of a therapy, select additional therapy, and monitor recurrent diseases [8-10].

One effective method for identifying HD-related gene-expression signatures is high-throughput transcriptome profiling. Over the decades, many RNA microarray studies on HD patients and controls using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurones, peripheral blood, and postmortem brain tissue have been published in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Indeed, some recent studies have already approached integrative bioinformatics analysis on some of those datasets, particularly from the blood [

11,

12], to identify the potential HD biomarkers using conventional statistical methods. However, identifying biomarkers from all genomic datasets is often unsuitable through conventional statistical methods [

13], particularly due to the unsuitability of these methods to elucidate the intricate relationship among gene expressions [

13]. Moreover, the large dimensional datasets are complex to visualize using these methods, making it hard to interpret the results [

13]. In order to overcome these limitations, scientists have recently utilized an integration approach of machine learning (ML) algorithms with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and nomogram analysis, which can systematically prioritize the genes and hence improve the efficiency of identifying a novel prognostic biomarker [

14]. Besides, this integrated approach can also predict if the features (genes) positively or negatively correlate with the disease [

14].

In this study, we developed a rigorous, multi-phase pipeline to identify reliable biomarkers for HD, integrating meta-analysis with interpretable ML (

Figure 1). We first identified a core collection of consistently dysregulated genes by meta-analysis of publicly accessible three postmortem HD-affected brain tissue microarray datasets from the GEO database using a lenient threshold to capture moderate yet consistent expression changes across samples. Subsequently, 19 supervised ML algorithms comprising tree-based classifiers including Decision Tree (DT), ExtraTrees (ET), Random Forest (RF), Gradient boosting (GB), Catboost (CB), ExtremeGradientBoosting (XGB), Adaptive Boosting (AB), Histogram Gradient Boosting (HGB), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM), as well as other classifiers consisting of Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Logistic Regression (LR), Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Support Vector Machine (SVM) with different kernels, Naive Bayes (NB), and Bernoulli Naive Bayes (BNB) have been used on the selected gene list to select features that best distinguish HD cases from controls. Finally, by combining the robustness of meta-analyses (stringent criteria) with the power of ML to choose features with high dimensions, we identified two potential biomarkers that obtained excellent predictive performance in independent validation and were strongly associated with HD risk.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have utilized three HD microarray datasets studied postmortem brain tissue to disclose a potential biomarker with prognostic value that can detect disease progression during the prolonged presymptomatic stage and monitor the treatment efficacy. Although efforts from previous studies on biomarker identification mostly rely on analyzing blood transcriptome profiling, the most reliable way to understand the molecular basis of disease processes specific to a particular tissue is by analyzing RNA expression in postmortem tissue, because of its sensitivity to local pathology, superiority to cell type resolution and lack of systemic confounding [25-27].

To find reliable biomarkers for HD, we used a two-step workflow in this study: first, a thorough meta-analysis of HD microarray datasets; and second, supervised ML. In many disease contexts, meta-analysis of microarray data has increased statistical power and reproducibility, providing a more meaningful understanding of the underlying biological processes [

28]. Our findings extend this paradigm to the discovery of HD biomarkers. In addition, this approach addresses sample heterogeneity by employing data aggregation, stringent quality control, and statistical modelling that explicitly considers inter-study variations [29-31]. We used two criteria for sorting the candidate DEGs (a relaxed and stringent), where a relaxed criterion (adjusted

p-value < 0.05, and absolute log2 fold change ≥ 0.85), which identifies 41 genes subjected to ML modeling. A lowered threshold (relaxed criterion) ensures the model picks up weak but biologically significant signals, keeping a broader range of potentially informative features. These genes may not meet stringent statistical cut-offs but could contribute meaningfully to classification performance. Perhaps, analysis of GO enrichment suggests that the dysregulation of these 41 genes is responsible for alterations in some essential signaling pathways, including synapse function and dendritic arborization, which are known to exacerbate HD pathophysiology [32-36] and contribute to motor and cognitive symptoms. Furthermore, striatal neurones, which are particularly affected in HD, show alterations in action potentials and membrane potentials, including changes in the patterns of action potential firing and a shift towards the depolarisation of resting membrane potentials, which are also associated with motor and cognitive symptoms [37-39].

To refine these candidates, we leveraged the strength of 19 ML classifiers, as not all models are suitable for all data types. For example, training a deep neural network with high-dimensional data of a few hundred patient samples will likely result in a highly overfitted model. Hence, it is necessary to carefully choose the right types of models a priori and not purely rely on brute force computational power [

40]. When estimating a model’s generalization performance from observational data, the variability in biomedical datasets is often high, due to both technical and biological sources of variation. To address this challenge, we evaluated each model using cross-validation to avoid hyperparameter-tuning bias and obtain nearly unbiased performance estimates [

41]. AUC selected the top three models from these ML models, providing consistent model evaluation. AUC evaluates the model using all thresholds, effectively addressing the effect of changing prevalence (proportion of positive cases). Models’ feature rankings were interpreted using SHAP, a game-theoretically grounded method that provides consistent, locally accurate attributions for any model class [

24]. By intersecting the top features across these three models, we distilled a consensus list of six genes, thereby reducing algorithm-specific selection biases and focusing on features with broad predictive relevance. Next, we reinforced reproducibility by re-applying meta-analysis with a stringent fold-change cut-off of 1.0, yielding 13 DEGs. The intersection of these 13 genes with our six consensus ML-selected genes produced a core set of five candidates. Crucially, this set was subjected to an external validation cohort by building a nomogram and ROC curve analysis, in which the final two biomarkers

GABRD and

PHACTR1, achieved AUCs of 1.00 and 0.98, respectively, confirming their high discriminative power and generalizability. Such performance in an external cohort underscores the robustness of our integrative approach and parallels outcomes seen in other ML biomarker studies with rigorous external testing.

The GABAAR δ subunit,

GABRD, was consistently given priority by the ML models, which aligns with the recognised role of GABAergic dysfunction in the development of HD. A previous study identified that

GABRD is abundantly expressed in the cerebellum, cortex, and hippocampus, localized in the cytosol and membranes of the neurons [

42]. Santhakumar et al observed that animals deficient in tonic GABA currents had decreased survival after an in vitro excitotoxic challenge with quinolinic acid, indicating a neuroprotective function against excitotoxic damage in the adult striatum [

43]. More importantly, in experimental settings,

GABRD is identified as a blood biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) detection by untargeted proteomics profiling, where

GABRD-positive neuronal extracellular vesicles represent synaptic dysfunction and neuronal death [

42].

On the other hand,

PHACTR1, which is implicated in dendritic arborization in the gene enrichment analysis, was repeatedly selected, highlighting novel facets of HD biology that warrant further mechanistic study.

PHACTR1 encodes protein phosphatase and actin regulator 1 that binds actin and protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) and plays a critical role in the actin cytoskeleton and dynamics.

PHACTR1 has been identified in the synaptosome, co-localizing with the synaptic marker synaptophysin, detectable in dendrites at DIV21, and strongly expressed in differentiated neurons within the adult mouse cerebral cortex [

44,

45]. Dendritic spine formation and synaptic plasticity are processes known to be impaired in HD, and they are supported by actin dynamics in neurons. Although there is a lack of direct mechanistic studies on

PHACTR1 in HD, a recent investigation revealed that

PHACTR1 is among a limited number of genes that are more prevalent in the striatum and whose dysregulation correlates with the emergence of somatic CAG repeats and neurodegeneration in HD murine models [

46].

Although our study, using an integrated bioinformatics and ML model, discloses GABRD and PHACTR1 as novel key biomarkers for HD, it still has certain constraints. Firstly, our work lacked any in vivo and/or in vitro validation experiments; instead, it exploited data from a public database to identify potential biomarkers. Secondly, further research is yet to be completed to understand intricately how these genes contribute to HD progression and corroborate their viability as diagnostic markers. Thirdly, the selected datasets had a limited sample size and were only collected from the GEO database. Finally, the selected datasets were processed using different platforms, and although we removed the batch effects using the “sva” package, they could still contain some degree of noise.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm their contributions to this manuscript as follows: Conceptualization, N.D. and R.D.; methodology, N.D. and M.A.B.; software, N.D.; validation, N.D. and M.A.B.; formal analysis, N.D. and M.A.B.; investigation, N.D. M.A.B., J.L., and R.D.; resources, R.D.; data curation, N.D. and M.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.D., M.A.B., and R.D.; writing—review and editing, N.D., M.A.B., and R.D.; visualization, N.D., M.A.B., J.L.; and R.D.; supervision, R.D.; project administration, R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the study for identifying key biomarkers in Huntington’s disease (HD). The study comprises three main steps: (1) Meta-analysis: Three brain tissue-related GSE datasets from distinct platforms were retrieved using the GEOquery package in R, preprocessed, and batch-corrected. Meta-analysis was performed using limma and MetaVolcanoR under both relaxed and stringent criteria. (2) Machine learning: Normalized batch corrected data is split into training and test sets. 19 ML classifiers were evaluated, and the top three models (based on AUC) were selected. SHAP analysis of these models identified six candidate genes. Five genes are considered robust biomarkers that overlap with candidate genes from ML, with the stringent meta-analysis DEGs. (3) Validation: A nomogram based on the five biomarkers was trained on the training data and validated using an external dataset. ROC curve analysis on the external set was performed, and the selected final biomarkers with strong discriminative power for HD were identified.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the study for identifying key biomarkers in Huntington’s disease (HD). The study comprises three main steps: (1) Meta-analysis: Three brain tissue-related GSE datasets from distinct platforms were retrieved using the GEOquery package in R, preprocessed, and batch-corrected. Meta-analysis was performed using limma and MetaVolcanoR under both relaxed and stringent criteria. (2) Machine learning: Normalized batch corrected data is split into training and test sets. 19 ML classifiers were evaluated, and the top three models (based on AUC) were selected. SHAP analysis of these models identified six candidate genes. Five genes are considered robust biomarkers that overlap with candidate genes from ML, with the stringent meta-analysis DEGs. (3) Validation: A nomogram based on the five biomarkers was trained on the training data and validated using an external dataset. ROC curve analysis on the external set was performed, and the selected final biomarkers with strong discriminative power for HD were identified.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis involves identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from GSE3790 and GSE26927. (a) Principal component analysis (PCA) plots illustrating the uniformity of datasets before and after batch effect removal, where the upper panel and lower panel represent the PCA plots before and following batch effect removal, respectively. (b) Volcano plot displaying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of the meta-analysis. Genes were considered significantly differentially expressed with an adjusted p-value (FDR) < 0.05 and an absolute log₂ fold change > 0.85. Genes that are significantly upregulated are represented in red, while downregulated genes are shown in blue, and non-significant genes are highlighted in grey. (c) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the normal and HD subjects found in the combined datasets.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis involves identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from GSE3790 and GSE26927. (a) Principal component analysis (PCA) plots illustrating the uniformity of datasets before and after batch effect removal, where the upper panel and lower panel represent the PCA plots before and following batch effect removal, respectively. (b) Volcano plot displaying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of the meta-analysis. Genes were considered significantly differentially expressed with an adjusted p-value (FDR) < 0.05 and an absolute log₂ fold change > 0.85. Genes that are significantly upregulated are represented in red, while downregulated genes are shown in blue, and non-significant genes are highlighted in grey. (c) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the normal and HD subjects found in the combined datasets.

Figure 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of 41 DEGs. (a) Gene enrichment analysis of the 41 genes identified the top enriched gene ontology terms, biological process (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular function (MF).

Figure 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of 41 DEGs. (a) Gene enrichment analysis of the 41 genes identified the top enriched gene ontology terms, biological process (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular function (MF).

Figure 4.

Performance assessment of 19 machine learning (ML) classifiers and selection of the top three classifiers for biomarker selection. (a) Heatmap showing the performance of 19 ML classifiers on the train and test sets, where each row represents a classifier and each column corresponds to a metric. Color intensity ranging from 0 to 1 (blue to red) reflects the relative performance of each model. (b) Confusion matrices of the top-performing models showcased how accurately each model classified HD and control by comparing the model’s predicted and actual labels. (c, d) The ROC curve of the top-performing classifier on the train and test datasets shows its ability to distinguish between HD and Control.

Figure 4.

Performance assessment of 19 machine learning (ML) classifiers and selection of the top three classifiers for biomarker selection. (a) Heatmap showing the performance of 19 ML classifiers on the train and test sets, where each row represents a classifier and each column corresponds to a metric. Color intensity ranging from 0 to 1 (blue to red) reflects the relative performance of each model. (b) Confusion matrices of the top-performing models showcased how accurately each model classified HD and control by comparing the model’s predicted and actual labels. (c, d) The ROC curve of the top-performing classifier on the train and test datasets shows its ability to distinguish between HD and Control.

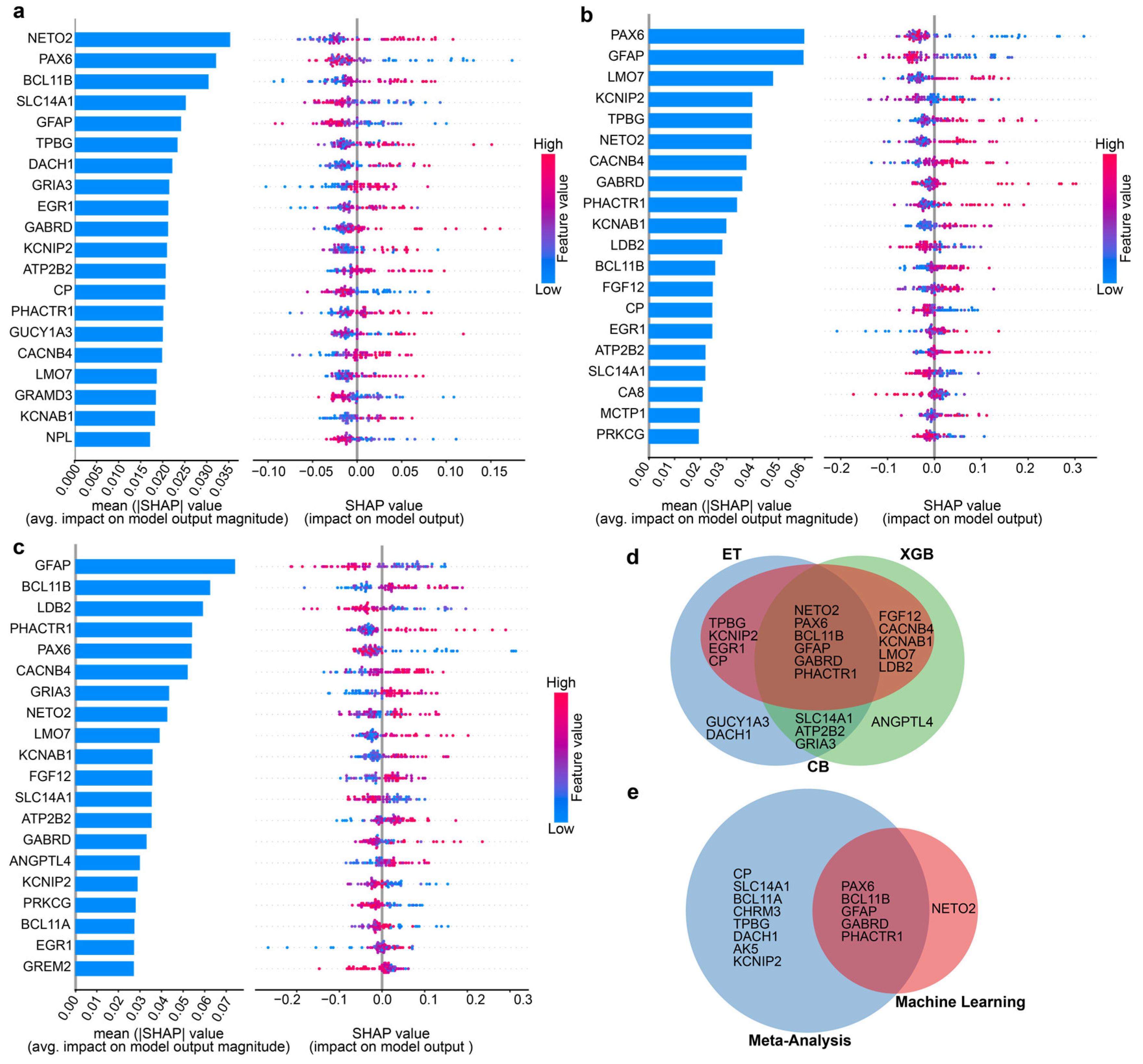

Figure 5.

Identification of five robust biomarkers through the integration of machine learning (ML) and DEG meta-analysis. (a, b,c) SHAP summary plots highlighting the significance of the top 20 genes for three top-performing ML classifiers: (a) ET, (b) CB, and (c) XGB. The SHAP summary plot illustrates the contribution from each gene to the model prediction for HD. The left panel (beeswarm plot) displays individual gene expression contributions, where each dot represents a sample and its corresponding SHAP value. The color gradient indicates gene expression levels, with red denoting high expression and blue indicating low expression. The right panel (bar plot) presents the average absolute SHAP value for each gene, summarizing its overall impact across all samples. The plot showcases the contribution from each gene to the model prediction for HD, where each dot represents a single gene expression value. While the red color represents high expression, the blue color represents low. (d) Six genes were consistently ranked among the top 15 features across all three models in SHAP plots across all three classifiers. (e) Five genes were selected as robust biomarkers as they overlapped with the candidate genes identified by ML and the DEGs found in meta-analysis using strict criteria.

Figure 5.

Identification of five robust biomarkers through the integration of machine learning (ML) and DEG meta-analysis. (a, b,c) SHAP summary plots highlighting the significance of the top 20 genes for three top-performing ML classifiers: (a) ET, (b) CB, and (c) XGB. The SHAP summary plot illustrates the contribution from each gene to the model prediction for HD. The left panel (beeswarm plot) displays individual gene expression contributions, where each dot represents a sample and its corresponding SHAP value. The color gradient indicates gene expression levels, with red denoting high expression and blue indicating low expression. The right panel (bar plot) presents the average absolute SHAP value for each gene, summarizing its overall impact across all samples. The plot showcases the contribution from each gene to the model prediction for HD, where each dot represents a single gene expression value. While the red color represents high expression, the blue color represents low. (d) Six genes were consistently ranked among the top 15 features across all three models in SHAP plots across all three classifiers. (e) Five genes were selected as robust biomarkers as they overlapped with the candidate genes identified by ML and the DEGs found in meta-analysis using strict criteria.

Figure 6.

Construction of a nomogram using the features identified by machine learning (ML) models and validation using the calibration curve and external datasets. (a) Nomogram for predicting the risk of developing HD using five features identified by ML models. First, a point was identified for each feature of a patient using the uppermost rule, and subsequently, all points were summed together to obtain the total number of points, and using the total points, the corresponding predicted probability of developing HD was found using the lowest rule. (b, c) The horizontal axis of calibration curves (b and c) represents the predicted probability of HD, while the vertical axis denotes the observed proportion of events that occurred inside the expected probability range. (d) ROC curve of the nomogram prediction model using the external validation dataset, signifying the validity and reliability of the model. (e) Decision curve analysis (DCA) of the nomogram, where the left panel represents the DCA curve of the external validation dataset and the right panel indicates the DCA curve of the ML training dataset.

Figure 6.

Construction of a nomogram using the features identified by machine learning (ML) models and validation using the calibration curve and external datasets. (a) Nomogram for predicting the risk of developing HD using five features identified by ML models. First, a point was identified for each feature of a patient using the uppermost rule, and subsequently, all points were summed together to obtain the total number of points, and using the total points, the corresponding predicted probability of developing HD was found using the lowest rule. (b, c) The horizontal axis of calibration curves (b and c) represents the predicted probability of HD, while the vertical axis denotes the observed proportion of events that occurred inside the expected probability range. (d) ROC curve of the nomogram prediction model using the external validation dataset, signifying the validity and reliability of the model. (e) Decision curve analysis (DCA) of the nomogram, where the left panel represents the DCA curve of the external validation dataset and the right panel indicates the DCA curve of the ML training dataset.