Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

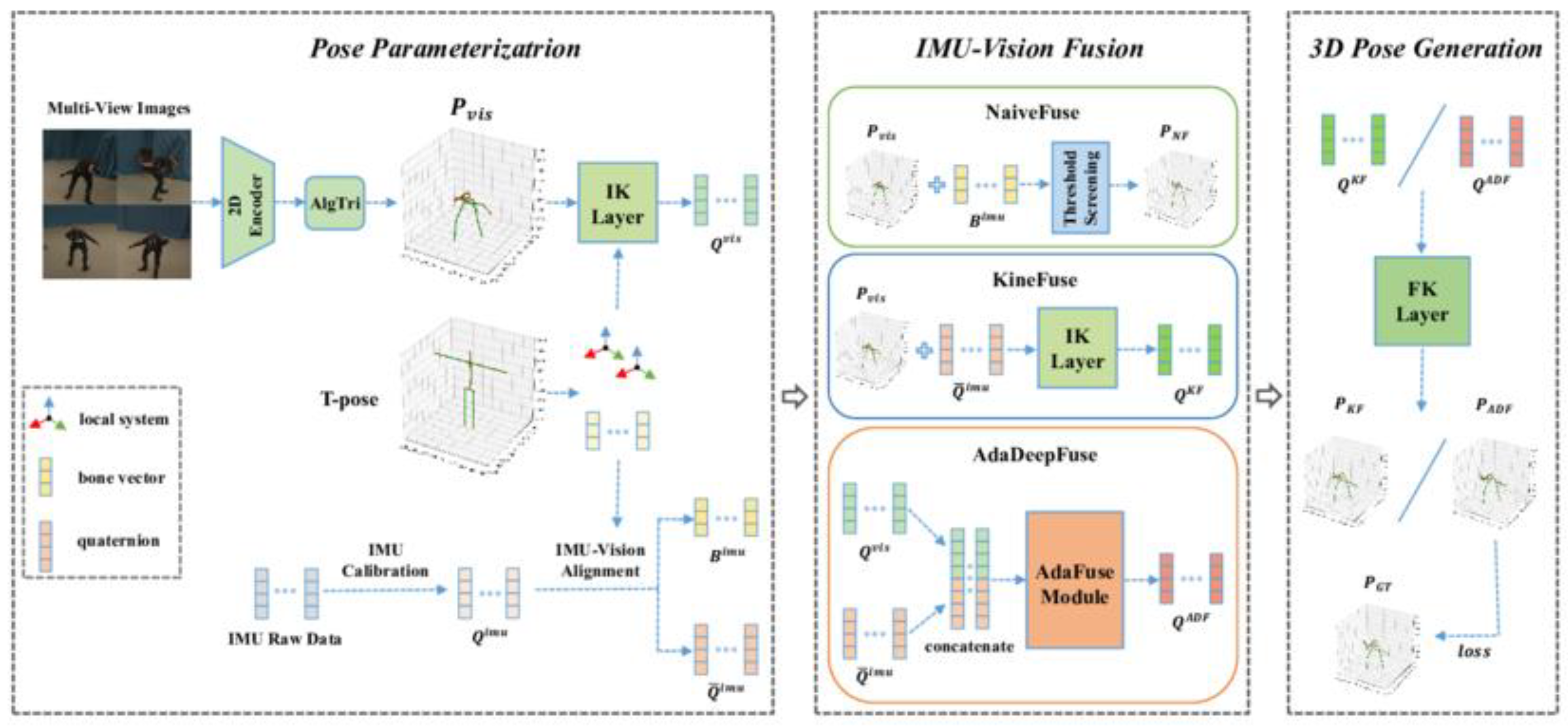

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Test Environment

2.2. Experimental Setup and Comparison

2.3. Measurement Method and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Equations

2.5. Repeatability and Error Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Multimodal Fusion Improves Pose Accuracy

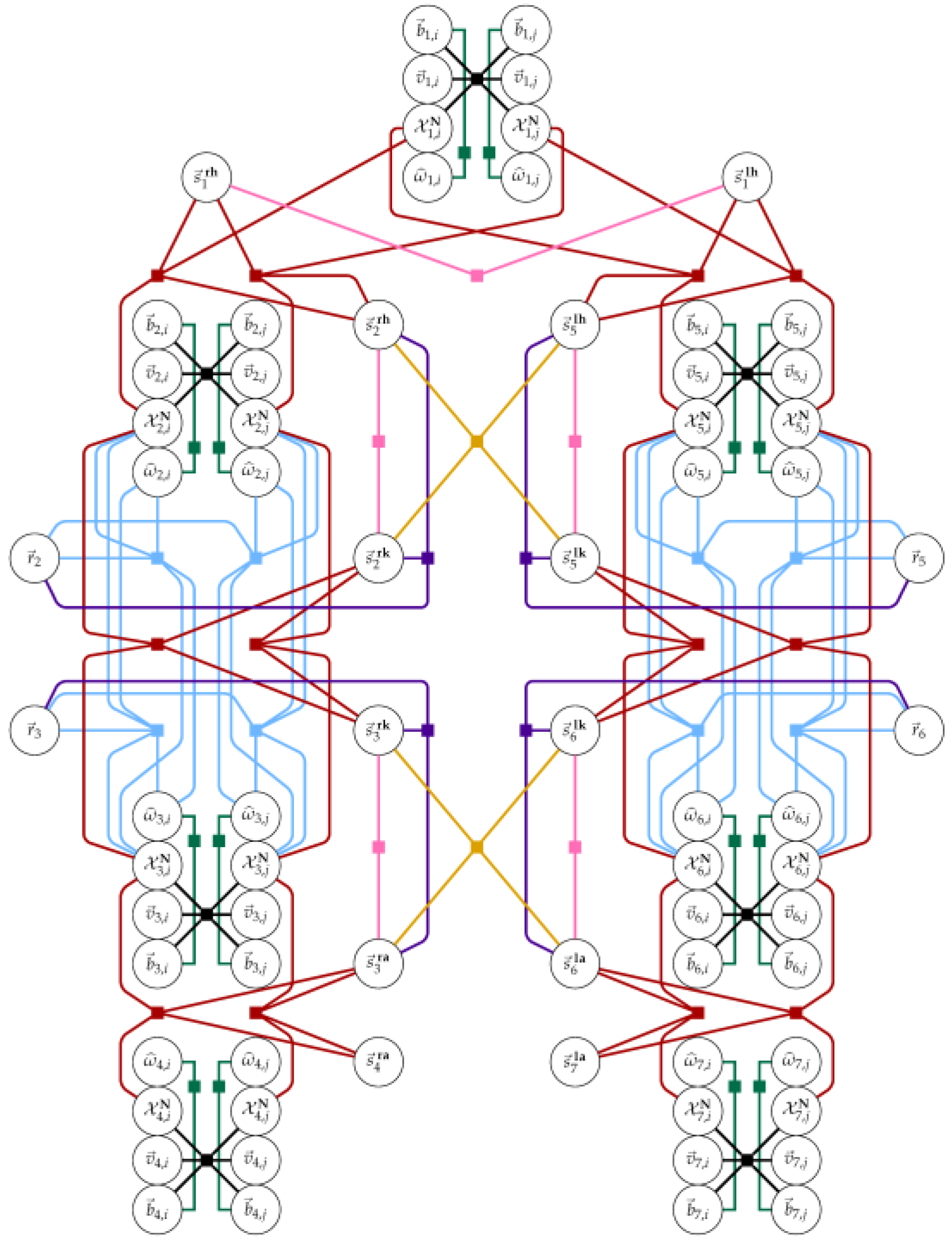

3.2. Drift Suppression via Graph-Based Optimization

3.3. Robustness under Occlusion and Missing Data

3.4. Comparison to Baseline Methods and Constraints

Conclusion

References

- Andrei, M.; Dulf, E.H.; Dénes-Fazakas, L.; Kovacs, L. (2024, July). Human Body Motion Tracking for Rehabilitation. In 2024 IEEE 28th International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems (INES) (pp. 000209–000214). IEEE.

- Yuan, M.; Wang, B.; Su, S.; Qin, W. Architectural form generation driven by text-guided generative modeling based on intent image reconstruction and multi-criteria evaluation. Authorea Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar]

- AMURRI, N. Evaluating Lifting Techniques: A Comparative Study of Kinematics and Dynamics Using IMU Sensors and the OpenCap Framework.

- Wu, C.; Zhu, J.; Yao, Y. (2025). Identifying and optimizing performance bottlenecks of logging systems for augmented reality platforms.

- Joseph, A.M.; Kian, A.; Begg, R. Enhancing Intelligent Shoes with Gait Analysis: A Review on the Spatiotemporal Estimation Techniques. Sensors 2024, 24, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Yasin, A.U.; Ul Haq, E.; Ali, M.; Kim, J.; Mehmood, A. Enhancing human activity recognition through integrated multimodal analysis: A focus on RGB imaging, skeletal tracking, and pose estimation. Sensors 2024, 24, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, T.; Nie, W.; Jiang, N.; Wang, J.; Su, W. Resilient Vision-Inertial Fusion Algorithm Based on the Depth of Feature Point. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, T.; Qin, F.; Lam, M.S.; Landay, J.A. (2022, April). Hybridtrak: Adding full-body tracking to vr using an off-the-shelf webcam. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Zhu, J.; Yao, Y. (2025). Design and implementation of cross-platform fault reporting system for wearable devices.

- Hu, W.; Huo, Z. (2025, July). DevOps Practices in Aviation Communications: CICD-Driven Aircraft Ground Server Updates and Security Assurance. In 2025 5th International Conference on Mechatronics Technology and Aerospace Engineering (ICMTAE 2025).

- Veesam, S. B. , Rao, B. T., Begum, Z., Patibandla, R. L., Dcosta, A. A., Bansal, S.,... & Al-Mugren, K. S. (). Multi-camera spatiotemporal deep learning framework for real-time abnormal behavior detection in dense urban environments. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 26813. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Smieszek, N.; Chakrapani, V. Unusually high electron affinity enables the high oxidizing power of layered birnessite. Chemistry of Materials 2021, 33, 7805–7817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewtz, M. (2025). Multi-Sensor and Multi-Modal Localization in Indoor Environments on Robotic Platforms (Doctoral dissertation, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT)).

- Chen, F.; Li, S.; Liang, H.; Xu, P.; Yue, L. (2025). Optimization Study of Thermal Management of Domestic SiC Power Semiconductor Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm.

- Rahimipour, M. (2025). Development of autonomous robot with multi-sensor fusion for visual-wheel-imu odometry.

- Sun, X.; Wei, D.; Liu, C.; Wang, T. Multifunctional Model for Traffic Flow Prediction Congestion Control in Highway Systems. Authorea Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Yang, J. (2025). Causal Assessment of Cross-Border Project Risk Governance and Financial Compliance: A Hierarchical Panel and Survival Analysis Approach Based on H Company’s Overseas Projects.

- Mahmood, A.S.; Al-Nuaimi, B.T.; Abdul-Wahab, A. Multi-cameras calibration system based deep learning approach and beyond: A survey. Bilad Alrafidain Journal for Engineering Science and Technology 2024, 3, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. (2025, September). Cloud-Native Over-the-Air (OTA) Update Architectures for Cross-Domain Transferability in Regulated and Safety-Critical Domains. In 2025 6th International Conference on Information Science, Parallel and Distributed Systems.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).