Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

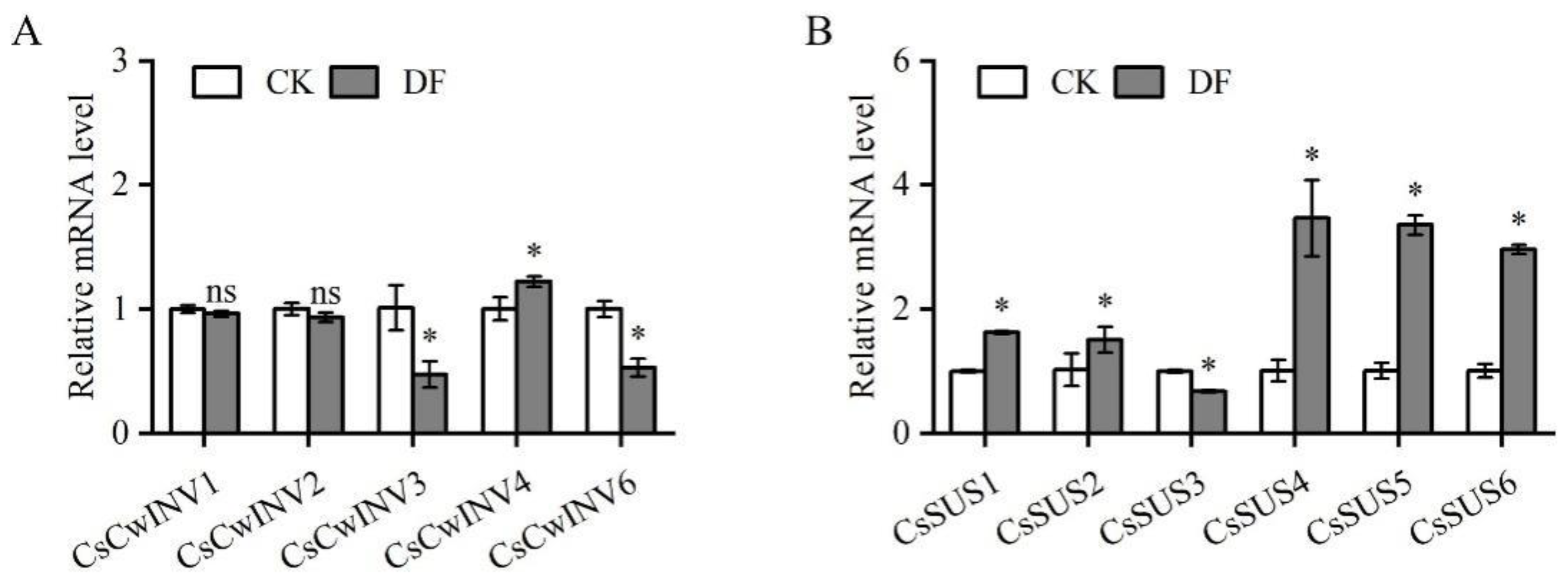

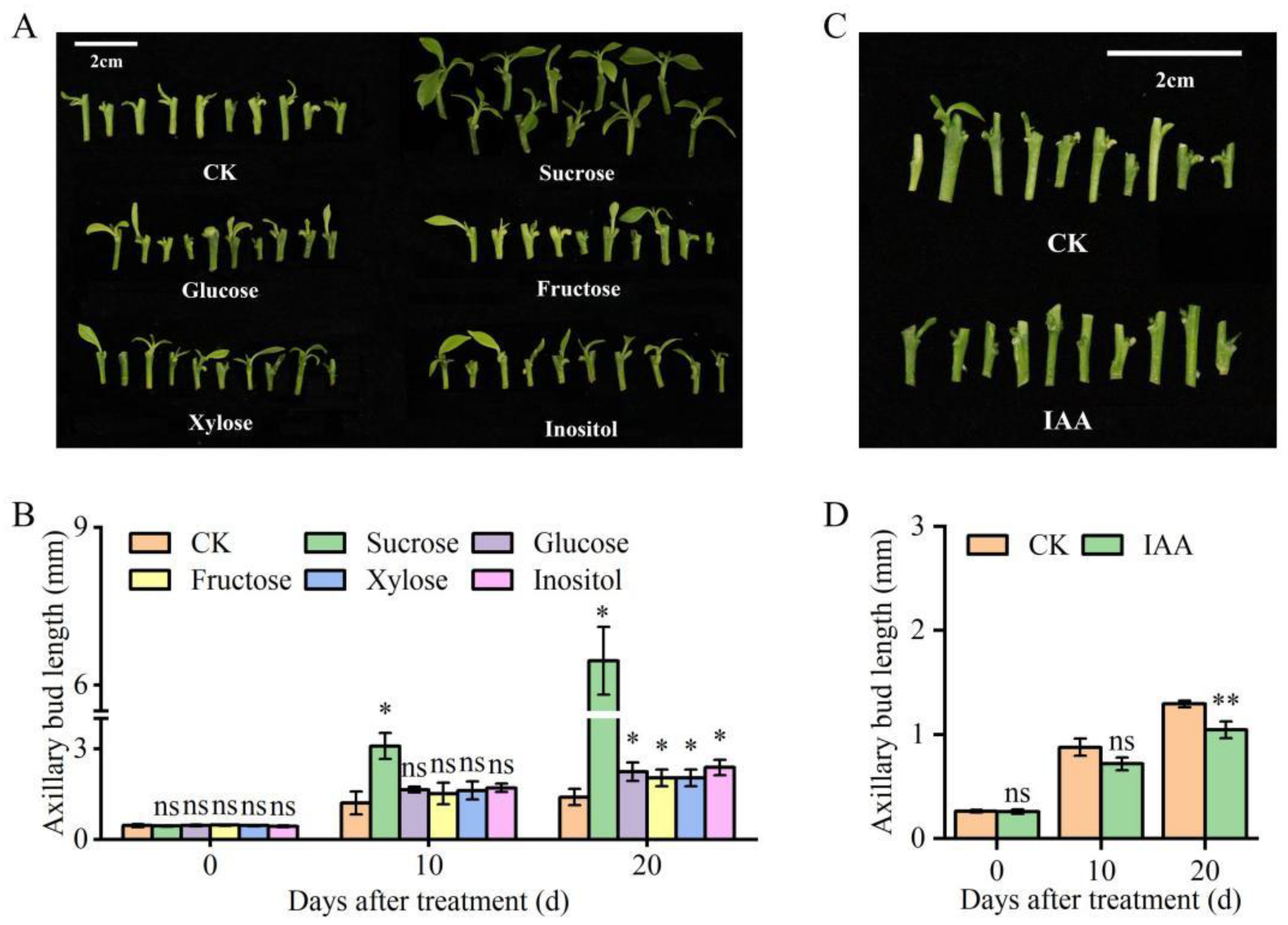

Excessively and randomly producing summer shoots will lead to difficulty in citrus orchard management, specially in pest and disease control. Heavy fruit load can reduce the summer shoot number. However, the mechanism is still unclear. In this study, field investigation and de-fruiting treatment confirmed that heavy fruit load reduces the number of citrus summer shoots, which is zero when the yield surpasses 3.3 kg per 125 dm3 of tree canopy. Metabolite analysis indicated that fruits at the cell expansion stage attract more soluble sugars and de-fruiting significantly increase the content of sugars and the transcript levels of sink strength-related genes, CsSUS4/5/6 to over 3.0 fold in the axillary buds. Moreover, exogenous application of some sugar-related DAMs (differently accumulated metabolites) such as sucrose obviously promoted axillary bud outgrowth. Taken together, these results confirmed that heavy fruit load plays a role in inhibiting axillary bud outgrowth or shoot branching primarily through competing for soluble sugars, which provides the basis for the inhibition of summer shoots by increasing the fruit load in citrus orchard and for the improvement of pest and disease management effectiveness.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Microscopic Observation of Axillary Bud Morphology and Length Calculation

2.3. Sugar Content Measurement

2.4. Hormone Content Measurement

2.5. The Application of Metabolites

2.6. RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fruit Load Affects the Number of Summer Shoots

3.2. Effects of De-Fruiting on the Development of Axillary Buds

3.3. Comparison of Sugar- and Hormone-Related Metabolites Between Fruits and Axillary Buds on Fruit-Bearing Shoots

3.4. Influence of De-Fruiting on Sugar and Hormone Levels in Axillary Buds

3.5. Influence of De-Fruiting on Sink Strength-Related Genes in the Axillary Buds

3.6. Influence of Applying Sugar-Related DAMs and IAA on Axillary Bud Outgrowth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Talon, M.; Caruso, M.; Gmitter, F.G. The Genus Citrus, 1 ed.; Talon, M., Caruso, M., Gmitter, F.G., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: 2020; ISBN 978-0-12-812163-4.

- Dawood Ahmed; Ranjan Sapkota, M. C., Manoj Karkee. Estimating optimal crop-load for individual branches in apple tree canopies using YOLOv8. Comput Electron Agric 2025, 229, 109697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doke, A.; Kakade, V.D.; Patil, R.A.; Morade, A.S.; Chavan, S.B.; Salunkhe, V.N.; Nangare, D.D.; Boraiah, K.M.; Thorat, K.S.; Reddy, K.S. Enhancing plant growth and yield in dragon fruit (Hylocereus undatus) through strategic pruning: A comprehensive approach for sunburn and disease management. Sci Hortic 2024, 337, 113562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.R.; Gossen, B.D.; Kora, C.; Parker, M.; Boland, G. Using crop canopy modification to manage plant diseases. Eur J Plant Pathol 2013, 135, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, J.B.; van der Krol, A.R.; Vos, J.; Struik, P.C. Understanding shoot branching by modelling form and function. Trends Plant Sci 2011, 16, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busov, V.B. Manipulation of growth and architectural characteristics in trees for increased woody biomass production. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, F.F.; Dun, E.A.; Kerr, S.C.; Chabikwa, T.G.; Beveridge, C.A. An update on the signals controlling shoot branching. Trends Plant Sci 2019, 24, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiao, Y. Axillary meristem initiation—a way to branch out. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2018, 41, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameau, C.; Bertheloot, J.; Leduc, N.; Andrieu, B.; Foucher, F.; Sakr, S. Multiple pathways regulate shoot branching. Front Plant Sci 2015, 5, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Khourchi, S.; Li, S.; Du, Y.; Delaplace, P. Unlocking the multifaceted mechanisms of bud outgrowth: advances in understanding shoot branching. Plants 2023, 12, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, S.R. The bud awakens: Interplay among hormones and sugar controls bud release. Plant Physiol 2023, 192, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Shi, L.; Wang, L.; Li, W. Interaction of phytohormones and external environmental factors in the regulation of the bud dormancy in woody plants. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 17200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Godin, C.; Boudon, F.; Demotes-Mainard, S.; Sakr, S.; Bertheloot, J. Light regulation of axillary bud outgrowth along plant axes: An overview of the roles of sugars and hormones. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, M.G. Concepts and terminology of apical dominance. Am J Bot 1997, 84, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, C.A.; Rameau, C.; Wijerathna-Yapa, A. Lessons from a century of apical dominance research. J Exp Bot 2023, 74, 3903–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-T.; Liu, D.-H.; Luo, Y.; Khan, M.A.; Alam, S.M.; Liu, Y.-Z. Transcriptome analysis reveals the key network of axillary bud outgrowth modulated by topping in citrus. Gene 2024, 926, 148623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, E.A.; Brewer, P.B.; Beveridge, C.A. Strigolactones: discovery of the elusive shoot branching hormone. Trends Plant Sci 2009, 14, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, D.; Leyser, O. Auxin, cytokinin and the control of shoot branching. Ann Bot. 2011, 107, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatfield, S.P.; Stirnberg, P.; Forde, B.G.; Leyser, O. The hormonal regulation of axillary bud growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J 2000, 24, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, P.B.; Dun, E.A.; Ferguson, B.J.; Rameau, C.; Beveridge, C.A. Strigolactone acts downstream of auxin to regulate bud outgrowth in pea and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2009, 150, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holalu, S.V.; Finlayson, S.A. The ratio of red light to far red light alters Arabidopsis axillary bud growth and abscisic acid signalling before stem auxin changes. J Exp Bot 2017, 68, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Finlayson, S.A. Abscisic acid is a general negative regulator of Arabidopsis axillary bud growth. Plant Physiol 2015, 169, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.J.; Dong, H.; Yin, Y.L.; Song, X.W.; Gu, X.H.; Sang, K.Q.; Zhou, J.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.H.; Foyer, C.H.; et al. Brassinosteroid signaling integrates multiple pathways to release apical dominance in tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118, e2004384118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robil, J.M.; Awale, P.; McSteen, P.; Best, N.B. Gibberellins: extending the Green Revolution. J Exp Bot 2025, 76, 1837–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Wang, J.G.; Wang, L.Y.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, Q.; Yu, P.; Bai, M.Y.; Fan, M. Gibberellin repression of axillary bud formation in Arabidopsis by modulation of DELLA-SPL9 complex activity. J Integr Plant Biol 2020, 62, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkilä, R.; Wybouw, B.; Smetana, O.; Vainio, L.; Solé-Gil, A.; Lyu, M.; Ye, L.L.; Wang, X.; Siligato, R.; Jenness, M.K.; et al. Gibberellins promote polar auxin transport to regulate stem cell fate decisions in cambium. Nat Plants 2023, 9, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Ende, W. Sugars take a central position in plant growth, development and, stress responses. A focus on apical dominance. Front Plant Sci 2014, 5, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Pérez-Garcia, M.D.; Davière, J.M.; Barbier, F.; Ogé, L.; Gentilhomme, J.; Voisine, L.; Péron, T.; Launay-Avon, A.; Clément, G.; et al. Outgrowth of the axillary bud in rose is controlled by sugar metabolism and signalling. J Exp Bot 2021, 72, 3044–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doidy, J.; Wang, Y.; Gouaille, L.; Goma-Louamba, I.; Jiang, Z.; Pourtau, N.; Le Gourrierec, J.; Sakr, S. Sugar transport and signaling in shoot branching. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 13214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, R.; La Camera, S.; Atanassova, R.; Dédaldéchamp, F.; Allario, T.; Pourtau, N.; Bonnemain, J.-L.; Laloi, M.; Coutos-Thévenot, P.; Maurousset, L.; et al. Source-to-sink transport of sugar and regulation by environmental factors. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelis, L.F.M. Sink strength as a determinant of dry matter partitioning in the whole plant. J Exp Bot 1996, 47, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K. Sucrose metabolism: regulatory mechanisms and pivotal roles in sugar sensing and plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2004, 7, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, F.; Barbier, F.F.; Feil, R.; Watanabe, M.; Annunziata, M.G.; Chabikwa, T.G.; Höfgen, R.; Stitt, M.; Beveridge, C.A.; Lunn, J.E. Trehalose 6-phosphate is involved in triggering axillary bud outgrowth in garden pea (Pisum sativum L.). Plant J 2017, 92, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, F.F.; Cao, D.; Fichtner, F.; Weiste, C.; Perez-Garcia, M.D.; Caradeuc, M.; Le Gourrierec, J.; Sakr, S.; Beveridge, C.A. HEXOKINASE1 signalling promotes shoot branching and interacts with cytokinin and strigolactone pathways. New Phytol 2021, 231, 1088–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stander, O.P.J.; Barry, G.H.; Cronjé, P.J.R. Fruit load limits root growth, summer vegetative shoot development, and flowering in alternate-bearing 'nadorcott' mandarin trees. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 2018, 143, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.M.; Samach, A. Constraints to obtaining consistent annual yields in perennial tree crops. I: Heavy fruit load dominates over vegetative growth. Plant Sci 2013, 207, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhai, G.; Li, X.; Tao, H.; Li, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Hong, G.; Zhu, Y. Metabolomics reveals nutritional diversity among six coarse cereals and antioxidant activity analysis of grain sorghum and sweet sorghum. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Deng, X.; Guo, L.; Gu, J. A novel bud mutation that confers abnormal patterns of lycopene accumulation in sweet orange fruit (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck). J Exp Bot 2007, 58, 4161–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, G.B.; Østergaard, L.; Chapman, N.H.; Knapp, S.; Martin, C. Fruit development and ripening. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2013, 64, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Magalhães, W.; Araújo, S.C.; Cecon, P.R.; Nogueira, M.A.; Martinez, H.E.P. Root growth, leaf and root chemical composition along coffee fruit development. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2025, 25, 1968–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadka, A.; Walker, C.H.; Haim, D.; Bennett, T. Just enough fruit: understanding feedback mechanisms during sexual reproductive development. J Exp Bot 2023, 74, 2448–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalom, L.; Samuels, S.; Zur, N.; Shlizerman, L.; Doron-Faigenboim, A.; Blumwald, E.; Sadka, A. Fruit load induces changes in global gene expression and in abscisic acid (ABA) and indole acetic acid (IAA) homeostasis in citrus buds. J Exp Bot 2014, 65, 3029–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.; Rabinovich, M.; Smith, H.M. The role of auxin and sugar signaling in dominance inhibition of inflorescence growth by fruit load. Plant Physiol 2021, 187, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Burgos, A.F.; Sáenz, J.R.R.; Quinchua, L.C.I.; Toro-Herrera, M.A.; Unigarro, C.A.; Osorio, V.; Balaguera-López, H.E. Increased fruit load influences vegetative growth, dry mass partitioning, and bean quality attributes in full-sun coffee cultivation. Front Sustain Food Syst 2024, 8, 1379207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.G.; Ross, J.J.; Babst, B.A.; Wienclaw, B.N.; Beveridge, C.A. Sugar demand, not auxin, is the initial regulator of apical dominance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111, 6092–6097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimann, K.V. Hormones and the analysis of growth. Plant Physiol 1938, 13, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertheloot, J.; Barbier, F.; Boudon, F.; Perez-Garcia, M.D.; Péron, T.; Citerne, S.; Dun, E.; Beveridge, C.; Godin, C.; Sakr, S. Sugar availability suppresses the auxin-induced strigolactone pathway to promote bud outgrowth. New Phytol 2020, 225, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.R.; Chen, Z.Q.; Zhang, K.Z.; Cui, J.T. The key role of sugar metabolism in the dormancy release and bud development of Lilium brownii var. viridulum Baker bulbs. Sci Hortic 2024, 336, 113453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, B. Auxin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 1997, 48, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, J.; Kalousek, P.; Reinöhl, V.; Friml, J.; Procházka, S. Competitive canalization of PIN-dependent auxin flow from axillary buds controls pea bud outgrowth. Plant J 2011, 65, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-Souza, L.; Yokoyama, R.; Sonnewald, U.; Fernie, A.R. Understanding source-sink interactions: Progress in model plants and translational research to crops. Mol Plant 2023, 16, 96–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, C.; Farina, V.; Mesejo, C.; Martínez-Fuentes, A.; Barone, F.; Agustí, M. Fruit regulates bud sprouting and vegetative growth in field-grown loquat trees (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.): Nutritional and hormonal changes. J Plant Growth Regul 2014, 33, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, C.; Mesejo, C.; Martínez-Fuentes, A.; Iglesias, D.J.; Agustí, M. Fruit load and root development in field-grown loquat trees (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl). J Plant Growth Regul 2013, 32, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinaga, K.; Imai, S.; Yakushiji, H.; Koshita, Y. Effects of fruit load on partitioning of 15N and 13C, respiration, and growth of grapevine roots at different fruit stages. Sci Hortic 2003, 97, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).