Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Abbreviations

1. Introduction

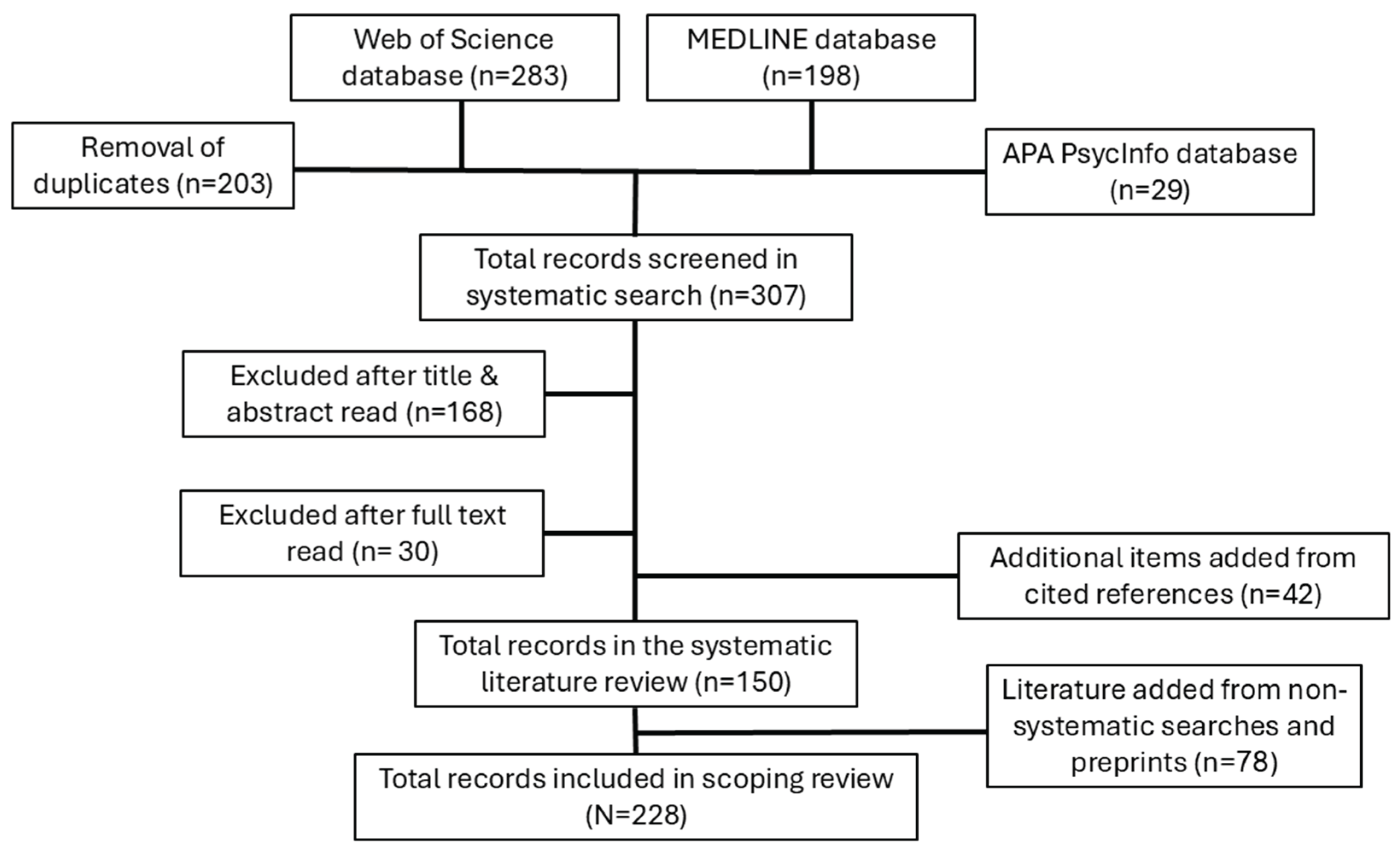

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data Charting

2.3. Additional Non-Systematic Searches for Subtopics and Preprints

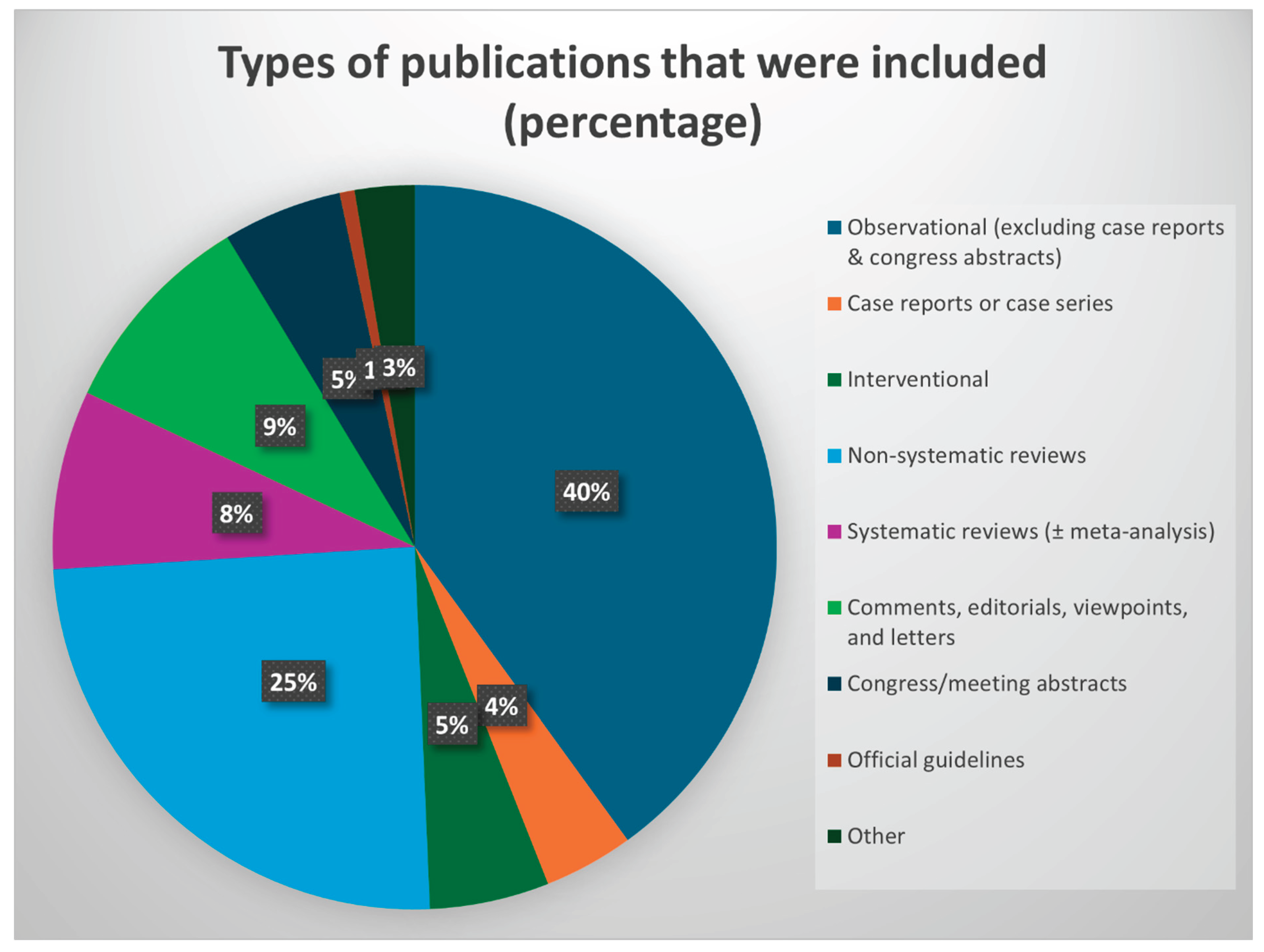

3. Part One- Findings from the Systematic Scoping Review

- Observational human studies (excluding case series, case reports, and conference abstracts) (n=60) [2,10,16,48,49,52,61,64,65,67,68,69,75,77,81,85,88,91,93,99,100,101,104,105,108,111,112,113,114,115,118,121,127,128,129,130,132,133,134,135,136,137,140,141,144,145,146,148,154,155,163,167,170,173,177,178,179,182,183,185]

- Official clinical guidelines (n=1) [186]

3.1. Definitions, Research Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria in LC studies, and Measurement Tools

3.1.1. Definitions & Research Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

-

COVID-19 individuals: COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals were seen defined differently across studies and involved different inclusion and exclusion criteria. A “COVID-19” individual was established either by self-report of the participant (e.g., based on symptoms consistent with COVID-19, a self-reported physician diagnosis of COVID-19, or self reported positive COVID-19 test), positive immunoglobulin response, a documented positive test in healthcare databases or COVID registries (e.g., PCR test), or by logical combinations of these conditions, for example. To give a specific example, in a study by Peterson et al. [75], symptomatic COVID-19 individuals were those who self-reported the symptoms that they had experienced during active COVID-19 infection from a list modified from the CDC and provided evidence of a previous positive PCR or antibody ELISA test indicating infection. On the other hand, the asymptomatic COVID-19 group consisted of those participants who self-reported no symptoms and had a previous positive PCR and/or positive antibody test (or self-reported that they had no symptoms but had a positive antibody test).In case of a non-LC (i.e., recovered COVID-19) infected individual, absence of persistent symptoms beyond a certain timeframe or the absence of symptoms altogether defined the convalescent group [91,185]. Such participants may have undergone a brief verbal screening to confirm no active symptomatology.Severity of acute illness: few studies stratified the COVID-19 group based on the severity of their acute COVID-19 illness (e.g., hospitalized vs. non-hospitalized).Additionally, unclear onset of symptoms was sometimes used as an exclusion criteria for self-reported COVID-19 [153].

- Controls and Healthy controls: were also seen defined differently across studies, depending on the study [81,91,104,115]. The heterogeneity in defining these crucial comparator groups has significant implications for interpreting research findings and understanding the true impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Healthy uninfected controls were often defined as individuals who have no prior history of COVID-19 infection, often confirmed through PCR and antibody testing, while other studies defined control groups as those with no active symptomatology or implementing both conditions [91]. Naturally, the longer the duration into the pandemic the more difficult it would have been for investigators to find non-infected individuals. Damasceno et al. (2023) [115] chose adults who had COVID-19 for at least 3 months prior to the data collection and without a chronic pain syndrome. Examples of inclusion criteria are (i) individuals that reported they did not have a confirmed objective COVID-19 test (e.g., PCR or home kit) [127], (ii) individuals that do not have a previous history of medical conditions as self-reported, (iii) no previous symptoms self-reportedly and negative result on the PCR and antibody test [75,118], and (iv) based on (absence of) diagnoses in medical records or healthcare registries. The non-infection healthy control group in Peterson et al., for example, were those who self-reported no previous symptoms and were negative on the PCR and antibody test administered immediately prior to carrying out the study’s investigation [75].

-

Long COVID, Post-COVID condition, Persistent COVID symptoms, and other parallel terms: A fundamental aspect of LC research is the definition used to identify affected individuals. Various studies employ different criteria, often aligning with guidelines from organizations like NICE and WHO, or developing their own definitions.A consistent inclusion criterion across many studies was, naturally, the persistence of symptoms for a defined duration following the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection (e.g., 4, 6, 12 weeks). Another additional inclusion condition often used for LC was confirmation of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection (by positive PCR, serology, self-reportedly, independent clinician, rapid antigen test with documentary proof from a health authority [159], or documentation in electronic health records). Some LC studies included only previously healthy individuals. Self-reported history of confirmed or probable COVID-19 infection according to WHO guidelines was also seen integrated into the inclusion criteria [91]. Certain studies focused on individuals experiencing a particular set of new persistent symptoms after acute COVID-19 [133], such as musculoskeletal pain [114] or neurological symptoms [182] whereas others focused on evident reduction in the level of functioning and activity or participation in daily life compared to before the infection [16]. Exclusion of alternative etiologies: some studies incorporated a process to rule out alternative medical etiologies for persistent symptoms, such as medical evaluations by physicians, or self-reportedly. Pre-existing chronic pain prior to COVID-19 infection, pre-existing chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia were sometimes part of the exclusion criteria [155].Examples of inclusion criteria for Post COVID/Long COVID/Chronic COVID/Subacute COVID/“persistent symptoms” or “non-recovery from COVID”: (i) participant self-reporting not to have been fully recovered after COVID-19 [146], (ii) participant self-reported physician-made diagnosis of LC [150], (iii) self-reported physician made diagnosis combined with a previous positive COVID-19 test [128], (iv) persistent symptoms beyond a specified interval of time (e.g., 12 weeks) [141,165], (v) presence of any persistent symptom since SARS-CoV-2 infection (or any persistent symptom among a predetermined list of symptoms) [93,99,185], (vi) persistent symptoms and negative Covid test for excluding active infection [75,154], (vii) based on the world health organization’s consensus definition [101], (viii) Bierle et al.’s (2021) criteria [144], (ix) fulfilling the official 2015 diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS [155], (x) persistent post-exertional malaise for 3 or more months verified by the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire [89], (xi) referral to- or diagnosis by- a post-Covid clinic, and more [137,156].A reader would notice correctly that some of the above examples can conflate “LC syndrome” and “persistent COVID symptoms,” which are not necessarily the same. Noteworthy, as opposed to simply including persistent symptoms, in case a syndrome is what investigators are aiming to investigate, defining LC for the purpose of a study as at least one persistent symptom, any symptom, even hyposmia, does not necessarily reflect a syndrome, in agreement with Phillips and Williams [8]. Lau et al. (2024) [159], for example, included individuals fulfilling the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for post-acute COVID condition and at least one of 14 symptoms included in their post-acute COVID-19 syndrome 14-item improvement questionnaire (PACSQ-14) for four weeks or more after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Matta et al. (2022) [185], in their widely cited publication of whether belief in having had COVID-19 and actually having had the infection (when verified by SARS-CoV-2 serology testing) were associated with persistent physical symptoms after COVID-19, in the context of LC, included individuals with at least one persistent symptom among a list of symptoms present for the past 4 weeks and lasting more than 8 weeks. That list consisted of headache, back pain, joint pain, muscular pain, sore muscles, sleep problems, fatigue, sensory symptoms such as pins and needles, tingling or burning sensation, skin problems, poor attention or concentration, hearing impairment, stomach pain, constipation, breathing difficulties, palpitations, chest pain, dizziness, cough, diarrhea, anosmia, and other symptoms.Eccles et al. (2024) [170] determined non-recovery from COVID-19 from a dichotomous self-reported response to the question “Thinking about the last or only episode of COVID-19 you have had, have you now recovered and are back to normal?” while Amsterdam et al. (2024) [133] recruited outpatients from a post-COVID clinic who, subsequent to non-hospitalized COVID-19, developed a prolonged illness, leading to a diagnosis of LC syndrome characterized by the persistence of one or more symptoms for over a month: dyspnea, cough, cognitive decline, brain fog, or fatigue, going by reference to the 2020 published NICE guidelines. Azcue et al. [141] took a similar approach and explicitly excluded respiratory symptoms persisting for 12 weeks post-infection, severe bilateral pneumonia, admission to an intensive care unit, or other manifestations necessitating hospitalization.

3.1.2. Assessment and Measurement Tools

- The visual analogue scale: for multiple measures such as pain and fatigue.

- Fatigue Severity Scale [128]: for assessing fatigue.

- Insomnia Severity Index: for the evaluation of insomnia [16].

- Fibromyalgia Symptom Scale (FSS) including the widespread pain index (WPI) and symptom severity scale (SSS) based on the ACR fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria and/or modified for self-administration [10,128], Fibromyalgia Rapid Screening (FIRST) questionnaire [135], and the central sensitization inventory (CSI) [146]: for assessment of fibromyalgia-type features, screening, or diagnosis. It is worth noting here that the CSI has not been validated to assess or measure central sensitization or neural activity [29], despite several studies using it for this purpose.

- Post-COVID-19 Functional Status (PCFS) self-reporting version: for assessing functional status post-COVID-19 infection.

- Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS) questionnaire: for assessing LC impact and need for rehabilitation in LC patients.

- Versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2, 8, 9): for depression assessment.

- Patient Health Questionnaire 15 (PHQ-15) for assessing somatic symptoms.

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [16] and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 scale: for anxiety assessment.

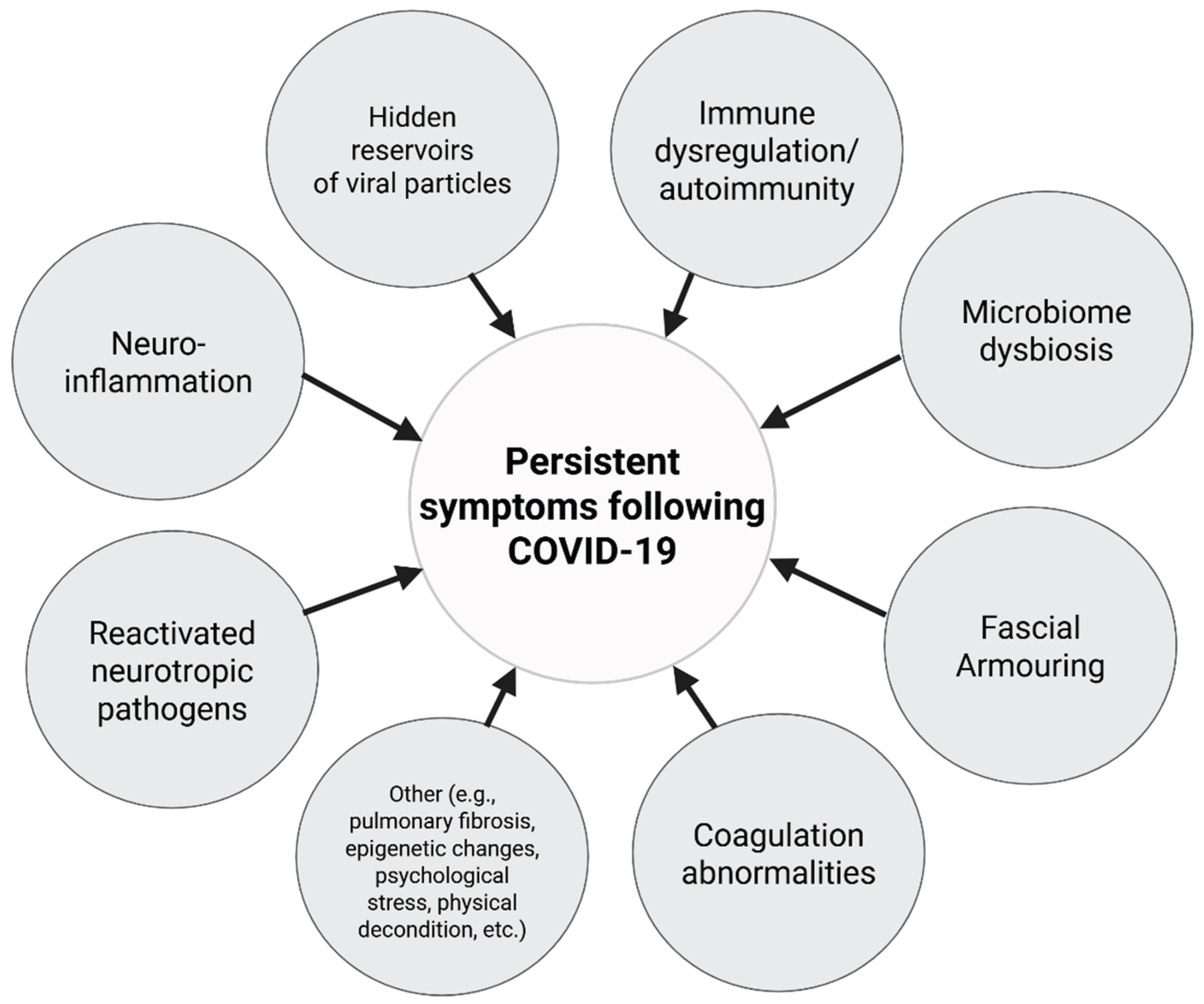

3.2. Long COVID-19 Mechanisms

3.3. Observational Studies on Widespread Musculoskeletal Pain and Fibromyalgia After SARS-CoV-2 Infection

3.3.1. Cross-Sectional and Cohort Studies on Post-Covid Fibromyalgia Prevalence and Incidence

3.3.2. Observational Studies on LC, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Overlapping Fibromyalgia (Molecular Mechanisms, Laboratory Investigations, and Others)

| Topic/Context | Study | Description of Study | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain after COVID-19 | Amsterdam et al. [133] | A cross-sectional survey via self-reported questionnaires explored the association between distinctive personality profiles, particularly type D personality, and LC among convalescent asymptomatic to mild acute-COVID-19 cases without a need for hospitalization or oxygen supplementation. Adult participants were recruited from a pool of 750 individuals undergoing follow-up at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center post-COVID-19 clinic as outpatients. | 31% completion rate yielded 114 respondents (74.6% women), mean age was 44.5 years. 68.4% were healthy prior to contracting COVID-19 and developing LC. 37 of 114 met diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, and in 28 (24.5%) it was a new diagnosis after COVID-19. None of the patients reported experiencing prior mental health issues, nor did they have previous psychiatric diagnoses. Clustering into two groups showed an association between more pronounced fibromyalgia features, a higher burden of depression and anxiety, diffuse pain, attention deficit, memory problems, headaches, perception of lower quality of life, and type D personality, as well as a trend towards poor sleep quality. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Damasceno et al. [115] | A case control study form Brazil that aimed to establish etiological factors associated with chronic pain syndromes in adult patients with post-COVID-19 conditions during 2021. Participants were adults who had COVID-19 at least 3 months prior to data collection with and without chronic pain syndromes. CSI was used to assess “central sensitivity” (i.e., fibromyalgia-type manifestations) | In total, 120 individuals were recruited (51 patients and 69 controls, average age ~30 years). CSI scores differed significantly between the groups with average scores of 50.51 in patients vs. 24 in controls (p < 0.001). |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Ebbesen et al. [105] | A nationwide cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence and risk factors of de novo widespread musculoskeletal pain after COVID-19 in non-hospitalized COVID-19 survivors. Demographic and medical data were collected through an online questionnaire from Danish adults with a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection at least 6 months prior to the study, between March 2020 and December 2021. Widespread pain was defined as participants experiencing pain in at least 2 sites of the body, in the upper part of the body and 1 site on the lower part. | Among 130,443 nonhospitalized respondents (58.2% women, mean age was 50.2 years), 5.3 percent (n=6,875) of nonhospitalized COVID-19 survivors had new-onset widespread musculoskeletal pain at approximately 14 ± 6.0 months after infection, which was rated as moderate to severe in its intensity in 75.6% of cases. In a multivariate analysis, female sex, age, higher BMI, and previous history of migraine, whiplash, stress, type-2 diabetes, and comorbid chronic neurological disorders, were found as risk factors for de novo widespread LC pain, with adjusted odds ratio of 1.549, 1.003, 1.043, 1.554, 1.562, 1.47, 1.56, and 1.532, respectively. Also, among a few other factors found to be significant, higher income was associated with less development of widespread pain. Time elapsed since infection was also significantly positively correlated. Rates differed according to stratification by SARS-CoV-2 variant. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Ketenci et al. [111] | A multicenter cross-sectional survey that was conducted during 2021 in physical and rehabilitative medicine outpatient clinics in Turkey categorized chronic pain after COVID-19 into predetermined categories. Diagnosis of pain phenotypes (nociceptive, neuropathic, or nociplastic/central sensitization) was made by physicians according to data from outcome measures including Pain Numerical Rating Scale, CSI, BDI, and HADS, Self-Report Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs, clinical examination, and their experience in musculoskeletal diseases. Patients with overlapping phenotypes were excluded. | In total, 437 patients were grouped by diagnosis into predetermined chronic pain phenotypes, and subjects with overlapping clinical features were excluded. 66.13% of the patients were diagnosed with nociceptive pain, 11.67% with neuropathic pain, and 22.20% with central sensitization based on the CSI (i.e., fibromyalgia-type features). According to the authors, central sensitization was associated with females, hypertension, physical activity, and pre-existing chronic disease prior to COVID-19. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Khoja et al. [112] | As part of a larger UK longitudinal study on musculoskeletal pain in LC (MUSLOC), cross-sectional data was reported on 30 adults with a history of COVID-19 with a diagnosis of LC and new onset musculoskeletal pain. The COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS) was used to capture the overall impact and health state before and after COVID-19 infection and the symptoms and their effect on individuals functioning. Other outcomes measures and self-assessment tools included QST and time up and go test, PHQ-9, GAD-7, PCS, EuroQol, and additional other tools. Central sensitization in participants was recognized if there was one of the three specific criteria: abnormally increased mechanical pain sensitivity, a reduced mechanical pain threshold, or presence of dynamic mechanical allodynia. | 30 participants in total (19 female) were included. The mean duration from the onset of musculoskeletal pain to evaluation in the study was 519.1 days (± 231.7). Only three participants were hospitalized due to COVID-19. Forty percent had no pre-existing medical condition. New-onset chronic musculoskeletal pain was mostly reported by the participants as generalized widespread pain (90%), characterized predominantly as joint pain. Ninety percent of the participants experienced continuous pain that always remains present, though its intensity may vary. 82.8% reported a high interference score, 19 participants stated that their employment status was affected by the health consequences associated with LC. QST indicated mechanical hyperalgesia and gain of function for wind up ratio, suggesting enhanced temporal summation of pain. In total, 25 participants (83%) showed central sensitization signs. There was a variability in the cytokine profiles. Investigation into individual cytokine levels using univariate analysis revealed no association between pain scores and any individual cytokines or C-reactive protein (CRP). The authors conclude that chronic new-onset musculoskeletal pain in LC tends to be generalized, widespread, continuous and is associated with central sensitization, elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, weakness, reduced function and physical activity, depression, anxiety, and reduced quality of life. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Khoja et al. [114] | An observational study that was conducted as part of a larger Musculoskeletal Pain in Long COVID (MUSLOC) UK study. Participants were adults (18 years or older) that tested positive for COVID-19 or had COVID-19 symptoms confirmed by an independent clinician, received a clinical diagnosis of post-COVID-19 syndrome according to the NICE guidelines, and experienced new-onset musculoskeletal pain since COVID-19. LC-associated symptoms were assessed using the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS) questionnaire. The assessment of fibromyalgia was conducted as part of the standard clinical examination and using the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 2010 criteria. | In total 18 patients were recruited, mean age was 49.6 (± 11.8) years, comprising 12 females (66.7%), mean duration since the onset of COVID-19 infection to the data collection point was 27.9 (± 6.97) months. Fourteen (77.8%) patients reported experiencing generalized widespread pain, while the remaining patients, who did not report widespread pain, still experienced pain in at least four distinct body areas. LC symptoms interfered with daily living activities for 17 (94.4%) patients, 13 (72.2%) of the evaluated patients met the diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia as defined by the ACR. The average WPI score among the patients was 8.8, indicating a high level of pain spread across multiple body regions. Additionally, the average SS score was 8.2, reflecting significant symptom severity related to fatigue, waking unrefreshed, cognitive symptoms, and the extent of other somatic symptoms. Patients that did not meet the high cut-off of the ACR criteria for diagnosis still had fibromyalgia features of widespread pain. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Kim et al. [127] | A 2022 cohort study that used data from electronic medical records from a nationwide population of all persons with COVID-19 in South Korea. Included were only individuals who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 during the first four months of the pandemic (February to May 2020) by means of real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Individuals in the control group were chosen as those who did not receive PCR testing. The authors investigated incidence rates of pain diagnoses of unspecified or idiopathic pain (e.g., fibromyalgia, headache, etc.), using diagnostic codes of the international classification, as well as prescription of medication as the outcome measures. | The diagnoses of fibromyalgia, temporomandibular joint disorders, and atypical facial pain did not occur at any time during 90 days from the index date. Opioid prescribed medications were higher in the COVID-19 group. When performing subgroup analysis the results were reversed, indicating higher rates of idiopathic pain in the control group. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Kim et al. [163] | A population-based cohort study to determine changes in the level of incidence of musculoskeletal disorders among the Korean population in pre-pandemic and during the pandemic (through the periods of 2018-2021), using electronic medical record registries of the Korean National Health Insurance Service. The incidence of orthopedic diseases was evaluated based on diagnostic codes of the international classification of diseases. | The incidence of myofascial pain had decreased during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels, while gout and frozen shoulder increased.. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Patel and Javed [19] | Case series from a pain clinic | Medical records of individuals who developed myofascial pain after a diagnosis of COVID-19 between March 2020 and December 2020 were obtained. Three patients with considerable pre-existing chronic pain conditions experienced worsening musculoskeletal symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection. The first patient, a 68-year-old female, developed post-COVID-19 myalgia and muscle spasms, which improved by 75% following trigger point injections and physical therapy. The second patient, a 35-year-old female with congenital scoliosis, developed bilateral shoulder pain post-COVID-19, with taut bands in the infraspinatus muscle, showing moderate improvement with conservative treatment but refusing intervention. The third patient, a 71-year-old male with a substantial orthopedic lumbar medical history, developed new-onset neck pain and headaches post-COVID-19, with palpable taut bands in the trapezius bilaterally (a total of six) referring pain to the occipital region, achieving 40–50% immediate pain relief after myofascial trigger point injections, resulting in a numerical pain rating scale rating of 3/10 (compared to 6/10 pre-intervention) during the 4 week follow-up. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Zha et al. [162] | Case report | A 59-year-old previously healthy Hispanic male developed persistent myalgia following COVID-19, with pain localized to trigger points in the neck, shoulders, upper back, arms, and legs, consistent with myofascial pain syndrome. Wet needling with lidocaine provided immediate but temporary relief, requiring multiple sessions over months. After experiencing a relapse associated with psychological stress, dry needling was introduced, leading to rapid and sustained pain reduction. |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Gouraud et al. [68] | A retrospective observational study from France investigated the characteristics, medical conclusions, and satisfaction of 286 patients with persistent symptoms after COVID-19 who attended a multidisciplinary day-hospital program. Evaluation was done by medical workup as recommended by official guidelines. | A total of 286 patients (of which 12.7% were hospitalized) were included in the study. The most common symptoms were fatigue, breathlessness, and joint/muscle pain. Cognitive and behavioral features that may contribute to the maintenance of physical symptoms were identified in 75.5% of patients after clinical evaluation and were considered as positive arguments in favor of a diagnosis of functional somatic disorder. Among these patients, 95.6% did not present any abnormal clinical findings or test results that could potentially explain the symptoms, and a diagnosis of functional somatic disorder was established for 72.2% of the patients after the multidisciplinary assessment. Patients with a diagnosis of functional somatic disorder had similar rates of major depression (32.8%) and anxiety disorders (25.0%) than in the whole sample, with no significant difference compared to those without (χ2 = 0.24, p = 0.63 and χ2 = 2.22, p = 0.14). |

| Pain after COVID-19 | Bakilan et al. [121] | A retrospective cross-sectional study aiming to evaluate frequency of musculoskeletal problems in post-acute COVID-19 patients. The study used medical records of LC adult patients who were admitted to the physical medicine and rehabilitation outpatient clinic in Tukey between December 2020 and May and who reported musculoskeletal symptoms. | 280 LC patients were included in the study (65% women, mean age 47.45±13.92, 70% not hospitalized). At admission to the outpatient clinic the frequency of symptoms of widespread myalgia was 3.9%, back pain 28.6%, and fatigue was 12.1%. Muscle pain in more than one site that was initiated or aggravated with COVID-19 was 51.1%. |

| Somatic symptoms in LC | Kachaner et al. [182] | A single-centre observational study from France that assessed the diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder (SSD) in patients with unexplained long-lasting neurological symptoms after mild COVID-19. Consecutive patients referred to a neurologist for post-COVID-19 consultation were reviewed. Main outcome was positive diagnosis of SSD according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders- 5 (DSM- 5). Brain MRI findings were extracted from patient records | 32 of 50 patients (64%) met the DSM-5 criteria for SSD. In the remaining 36%, SSD was considered possible given the high scores on diagnostic scales. Physical examinations were normal for all patients. Brain MRI showed unspecific minor white matter hyperintensities in 17% (8/46) of patients, considered non-specific findings, consistent with prevalence in the general population of that age range. Neuropsychological assessment (in 15 patients) showed exclusively mild impairment of attention in 93% (14/15), in discrepancy with their major subjective complaint. A high proportion of patients (90%, n=45/50) met criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome. A significant number of patients screened positive for mood-anxiety disorders (32%, n=17/50), had a history of prior SSD (38%, n=19/50), and reported past trauma (54%, n=27/50). Self-survey results highlighted post-traumatic stress disorder in 28% (12/43), high levels of alexithymia traits (42%, n=18/43), and high levels of self-oriented perfectionism (79%, n=33/42) |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | Das et al. [61] | A study that investigated genetic risk factors associated with ME/CFS using combinatorial analysis on genotype data from 2,382 ME/CFS patients reporting a diagnosis in the UK Biobank Pain Questionnaire, matching them against 4,764 controls. | The study stratifies ME/CFS patients genetically and correlates this stratification with clinical criteria. Biological analysis of identified genes reveals links to key cellular mechanisms hypothesized to underpin ME/CFS, such as vulnerabilities to stress and infection, mitochondrial dysfunction, sleep disturbance, and autoimmune development. |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Akel et al. [132] | A 2022 web-based cross-sectional study “to investigate the prevalence and predictors” (associated factors) of fibromyalgia in individuals recuperating from COVID-19, based on the study of Ursini et al. (2021). The ACR survey criteria were used with a cutoff score ≥ 13. | Out of 404 respondents (75% women, mean BMI 26.6, mean duration of COVID-19 infection was 12.8 ± 5.3 days) 89% were treated at home, while only six (1.5%) patients needed a ward admission and one (0.2%) an intensive care unit admission. 80 individuals (19.8%) satisfied the ACR survey criteria for fibromyalgia (out of them 93.8% were women). Females (OR: 6.557, 95% CI: 2.376 - 18.093, p = 0.001) and dyspnea (OR: 1.980, 95% CI: 1.146 - 3.420, p = 0.014) were associated with post-COVID-19 fibromyalgia. The fibromyalgia group had more pre-existing comorbidities. In bivariate correlation analysis age (r = 0.200, p = 0.001) and duration of COVID-19 infection (r = 0.121, p = 0.015) were said to be weakly correlated with fibromyalgia symptom score. |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Bileviciute-Ljungar et al. [16] | A Swedish web-based survey combined with face-to-face interviews, using several questionnaires inquiring into mood, pain, fibromyalgia criteria, functional status, and quality of life. The study included adults who had COVID-19 according to anamnesis or a positive test, and self-reported a significantly reduced level of functioning and persistent symptoms for more than 12 weeks. | A total of 100 individuals (82% female), at a mean of 47 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection, 90% were not hospitalized for COVID-19. Irritable stomach, pain in varied sites, and widespread pain were reported by 75%, 15%, and 50%, respectively (30 out of the 50 with widespread pain were healthy prior to their infection) with a mean pain intensity of 5.16 in the latter. 40 out of 100 fulfilled fibromyalgia criteria, of them 22 indicated being healthy before their infection. Previous comorbidities were found to be associated with generalized pain and with fibromyalgia. Health-related quality of life was decreased in more than 80 percent of individuals, not surprising considering the study’s inclusion criteria. |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Ganesh et al. [52] | Descriptive paper of 108 patients seen at a Post-COVID clinic at Mayo Clinic during 2021. Clinical symptoms were analyzed and assigned to one of six phenotypes: dyspnea, chest pain, myalgia, orthostasis, fatigue, and headache predominant. Patients with no evidence of tissue damage on testing were determined as likely to have a central sensitization phenotype, which was treated with a virtual treatment program aimed at patient education with elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, health coaching, and paced rehabilitation. The fatigue-predominant, myalgia-predominant, and orthostasis-predominant phenotypes were considered together as central sensitization phenotypes. | 108 fibromyalgia-type patients were seen (75% female, median age of 46 years, 16% were admitted for acute COVID-19). Patients were evaluated on average 148.5 days after the onset of symptoms (interquartile range, 111.5 to 179.3 days). The most common comorbidities were obesity (39%), anxiety (33%), depression (28%), and gastrointestinal disease (25%), while only 5% had irritable bowel syndrome. At the time of evaluation, the most common symptoms were fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog, anxiety, and unrefreshing sleep. Patients were classified into six phenotypes: fatigue predominant (n=69), dyspnea predominant (n=23), myalgia predominant (n=6), orthostasis predominant (n=6), chest pain predominant (n=3), and headache predominant (n=1), with more women being predominant for fatigue, orthostasis, and chest pain. The “central sensitization” phenotype (n=82) had statistically significantly higher IL-6 levels (P=.01), and higher proportion of women (82%) compared to other phenotypes of post-covid symptoms (54%; P<.0001). Age was not significantly different. |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Jennifer et al. [129] | A 2022 population based retrospective cohort study using data from electronic healthcare database and a COVID registry, during March 2020 and May 2021, investigating incidence rates of several medical conditions following COVID-19 (including deep vein thrombosis, lung disease, fibromyalgia, diabetes, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, acute kidney disease, hypertension, use of antidepressants/anxiolytics as an indication of depression/anxiety, and use of benzodiazepines as an indication of sleep disturbance). Records for out-patient and community-based physician or other health profession visits were used. Diagnosis of fibromyalgia was based on hospital and community-based physician visit diagnoses. | Slightly higher crude incidence rates were found for depression/anxiety, sleep disturbance, fibromyalgia (0.28% new cases compared to 0.24% in controls p = 0.034 in non-hospitalized cases), deep vein thrombosis, lung disease, and diabetes among convalescent persons after COVID-19. |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Martin et al. [125] | Patients recruited from a post-COVID-19 infection clinic were assessed at 6 months using the widespread pain index (WPI), symptom severity scale (SSS), 10 point visual analogue scale for fatigue severity (VAS-F) and a 9-item, 7-point fatigue severity scale. (congress abstract) | At six months following infection, five patients out of 25 recruited in total met criteria for fibromyalgia based on the WPI and SSS. Female patients and patients younger than 60-years-old had higher scores. |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Miladi et al. [131] | A web-based cross sectional survey during February 2022 to estimate the prevalence of fibromyalgia in patients who recovered from COVID-19 and to identify associated factors. ACR Survey Criteria and the Fibromyalgia Rapid screening Tool (FIRST) questionnaire were used. (meeting abstract) |

A total of 150 respondents (66% women) at an average of 6 ± 3 months after the COVID-19 diagnosis, majority in the age group of 21-30, 31% of responders had comorbidities, median BMI was 24.7. Median COVID-19 duration was 7 days with 0,7% of patients requiring hospital admission. ~19% screened positive with the FIRST questionnaire for fibromyalgia. Seven of the 29 subjects with fibromyalgia had seen a physician after the occurrence of widespread pain. Post-COVID-19 fibromyalgia was significantly associated with females (p = 0.003), comorbidities (p = 0.01) and obesity (0.03). |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Scherlinger et al. [118] | A prospective observational study from France that aimed to describe the clinical and biologic characteristics of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Consecutive patients seeking medical help for persistent symptoms self-attributed to COVID-19 during the first wave (February to April 2020) of the pandemic underwent a multimodal evaluation. Results were compared to convalescent COVID-19 individuals without persistent symptoms. The study also aimed to investigate the potential underlying mechanisms, including autoimmunity and psychological distress. | 30 patients (60% women) were included in total (7 visited the emergency department, 1 was hospitalized for COVID-19). Patients were clinically evaluated after a median of 152 days following the reported onset of initial symptoms (symptom persistence was median of 6 months duration). Seventeen (56.7%) reported a resolution of initial symptoms after a median of 21 days (IQR 15–33), followed by a resurgence at a median of 21 days later (IQR 15–44). Persistent symptoms had a cyclical pattern in 28 (93.3%) patients and were mostly represented by fatigue, myalgia and thoracic oppression Fatigue was severe for most patients and rated at a median of 7 (IQR 5–8) on a 10-point scale, with pain rated at 5 (IQR 2–6). The DN4 questionnaire screening neuropathic pain was positive (≥ 4/10) for 50% (15/30) of patients, and the FiRST questionnaire screening for fibromyalgia-like symptoms was positive (≥ 5/6) for 56.7%. For most clinical features there was no significant difference between immunized and non-immunized individuals. A clinical examination, including neurologic examination, was unremarkable. Nasopharyngeal and stool samples for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR tests were negative. Routine biologic test results were within normal limits for all but one patient (iron-deficiency anemia). Screening for autoimmunity revealed low (1/160) and medium (1/320 to 1/640) titers of anti-nuclear antibodies in 12 and 3 patients, respectively. Low to medium anti-nuclear antibody titers were numerically more prevalent in SARS-CoV-2 immunized than non-immunized patients (66.7% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.067). 10% (3/30) and 26.7% (8/30) of patients had a previous history of depression and anxiety disorders, respectively. HADS screening for anxiety and depression was positive for 11 (36.7%) and 13 (43.3%) of patients, respectively. Only half of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome patients had cellular and humoral immunity for SARS-CoV-2. |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Shani et al. [134] | A retrospective cohort study that investigated the associations between the BNT162b2 vaccine, infection with coronavirus, and the incidence of new registered diagnosis of autoimmune disease within ~1 year follow-up using electronic medical records of a large healthcare database. Vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals were compared as a cohort, and infected and uninfected as another cohort. The minimum follow-up time was four months, during the first phase of the pandemic. Included were individuals 12 years of age and above. Findings were reported in hazard ratios (HR) and incidence rates per 100,00 person years. Statistical analysis included incidence rate ratio tests (univariate), and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models with time-dependent exposure status. Correction for multiple comparisons was applied using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method to account for the investigation of multiple clinical outcomes. | More than 3 million were included with considerable differences between group characteristics. Vaccination did not influence rates of new registered diagnosis of fibromyalgia in any age group within the timeframe of the study. Infection with COVID-19 increased the risk for fibromyalgia (HR=1.72 95 % CI: 1.36–2.19 in individuals aged 18–44, HR = 1.71, 95 % CI: 1.31–2.22 in individuals aged 45–64) and hypothyroidism (in individuals aged 65 or older). The authors note that the process of reaching diagnoses in the primary care setting in many circumstances is not immediate, therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Sørensen et al. [65] | A nation-wide cross-sectional survey collecting data on self-reported symptoms using web-based questionnaires in Denmark via national e-Boks system (with access to 92% of all residents aged 15 years and above). Cases were chosen based on RT-PCR positive tests that were recorded in the national COVID-19 tracking system. Data were collected from August 1, 2021 to December 11, 2021. Questionnaires evaluated post-COVID symptoms and register-based information supplemented data on risk differences in new onset diagnoses of anxiety, chronic fatigue syndrome, depression, fibromyalgia and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) confirmed by a medical doctor since the test (onset between time of testing and questionnaire completion). | 153,412 individuals fully completed the questionnaire, 61,002 participants tested positive for sars-cov-2. There were significant differences in population characteristics between the study groups (in age, sex, physical activity, and more). Based on the statistical analysis of the findings, at least one diagnosis of depression, anxiety, chronic fatigue symptom (CFS), fibromyalgia, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) of new onset within the first 6, 9, or 12 months after the test was reported by 7.2% of individuals with a positive COVID test, compared to 3.3% of negatives. Risk for fibromyalgia was not found to be significantly different between the groups, amounting at 1% in COVID positive compared to 1.1% in COVID negatives (risk difference 0.02 95% CI: -0.09-0.14). |

| Fibromyalgia after COVID-19 | Ursini et al. [10] | A cross-sectional online survey via social network among Italian speaking adult individuals (≥18 years) who developed COVID-19 three or more months prior to the study, with the objective of estimating fibromyalgia prevalence after COVID-19. The Fibromyalgia Symptom Scale, based on the ACR 2016 criteria, was used to identify fibromyalgia by a cutoff score of 13. | 616 eligible individuals completed the survey, (77.4% women). In total, 30.7% fulfilled criteria appropriate for classifying fibromyalgia, 6 months on average after contracting COVID-19. Fibromyalgia was associated with a more severe acute infection, obesity, and with males. |

| Fibromyalgia and LC | Calvache-Mateo et al. [104] | A cross-sectional study from Spain aiming to assess clinical and psychological variables among non-hospitalized adult patients with LC, compared to recovered patients after COVID-19 and healthy controls. Outcomes were assessed using questionnaires such as the brief pain inventory, CSI, insomnia severity index, Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia, Pain Catastrophizing Scale, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, and Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, and analyzed using chi-squared and ANOVA tests to identify group differences. | 170 participants in total (healthy control group n = 58, successfully recovered group n = 57, and LC group n = 55, mean age ~45 years for all groups). Mean CSI (indicating fibromyalgia-type features with a conventional cutoff score of 40) for the LC group was 54.53 ± 17.10 at 105 ± 12 weeks since infection on average, which was significantly higher compared to recovered patients (18.81 ± 16.24) and healthy controls (17.69 ± 14.30). Brief pain inventory and insomnia severity index were also significantly higher in the LC group, as well as rates of pharmacological treatment. Scores for the pain catastrophizing scale components relating to helplessness were 9.93 ± 5.70 compared to 2.16 ± 3.09 in the COVID-19 recovered group. No statistically significant differences were found between the healthy control group and the successfully recovered COVID-19 patients in any variable. |

| Fibromyalgia and LC | Hackshaw et al. [135] | A pilot study aiming to develop a metabolic fingerprint approach for diagnosing clinically similar LC and fibromyalgia using Fourier-transform mid-infrared spectroscopic techniques for analysis. Fifty fibromyalgia and 50 LC patients were recruited. Spectral data were split into two sets randomly to train and externally-validate a predictive algorithm for making diagnosis. The relative percentage area of each IR band in the region of 1500 to 1700 cm−1 was taken. Chemometric analysis was then done to analyze the spectral data. | 50 subjects in the LC group (64% female) and 50 in the fibromyalgia group (100% female), and 6 controls. The deconvolution analysis of spectral data identified a unique spectral band at 1565 cm−1, linked to glutamate which was present only in fibromyalgia patients. The Orthogonal Signal Correction Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis classified spectra with high accuracy and specificity in the subgroup of external validation. Differences in the population demographic characteristics and medication history potentially introduced confounding factors. |

| Fibromyalgia and LC | Haider et al. [128] | A cross-sectional study to characterize pain, fatigue, and function in individuals reporting post-COVID-19 and compare the clinical phenotype to those with fibromyalgia and ME/CFS. Included were adult individuals that self-reported a physician diagnosis of LC, fibromyalgia, and/or CFS, and were given self-report outcome measures to assess fatigue, dyspnea, pain, quality of sleep, catastrophizing, kinesiophobia, depression, anxiety, cognitive function, and physical function. The study’s survey was distributed by e-mail and research websites targeting patients, faculty, and staff through the University of Iowa. | 707 respondents included in the final analysis: 203 had LC, 99 fibromyalgia, and 87 ME/CFS, while the rest had more than one of these diagnoses in combination. Individuals with post-COVID-19 reported mild to moderate fibromyalgia symptom severity, with 8.4% scoring 13 or higher on the fibromyalgia severity score. The fibromyalgia severity score was significantly lower in the post-COVID-19 group when compared to all groups with fibromyalgia and was similar to those with ME/CFS. Individuals with post-COVID-19 reported lower multisensory sensitivity compared to fibromyalgia and fibromyalgia+ME/CFS (p<.001). Overall LC respondents reported multiple symptoms that overlap with fibromyalgia and ME/CFS, but with less severe fatigue compared to ME/CFS and less severe pain compared to fibromyalgia. |

| Fibromyalgia and LC | Hyland et al. [64] | A study that conducted a symptom network analysis of LC, ME/CFS irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), fibromyalgia, severe asthma, and a healthy control group to provide insight into the etiology of medically unexplained symptoms. Participants completed a 65-item questionnaire assessing psychological and somatic symptoms, and a network analysis was conducted taking the 22 symptoms that best discriminated between the six groups. Connectivity, fragmentation, and the number of symptom clusters were then assessed to determine relationships between symptoms and underlying causes. | Among 2,164 subjects, the symptom networks of LC and ME/CFS differed. When compared to LC, there was significantly lower connectivity, greater fragmentation and more symptom clusters in ME/CFS, IBS, and fibromyalgia. Although the symptom networks of LC and ME/CFS differed, the variation of cluster content across the groups was inconsistent with a modular causal structure but rather consistent with a connectionist biological basis of medically unexplained symptoms. |

| Fibromyalgia and LC | Nuguri et al. [136] | A follow-up study of the 2023 Hackshaw et al. [135] study to differentiate fibromyalgia from LC based on a metabolic signature. Venous blood samples were collected from LC and fibromyalgia patients using both dried bloodspot cards and volumetric absorptive micro-sampling tips. Data were acquired using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). | Amide groups, aromatic and acidic amino acids patterns could help discriminate between fibromyalgia and LC. The study demonstrates the potential of SERS in identifying unique metabolites that can be used as spectral biomarkers to differentiate fibromyalgia from “LC”. |

| Fibromyalgia and LC | Saito et al. [81] | A study of immunological dysregulation, chronic inflammation, and impaired erythropoiesis in LC individuals compared to recovered and healthy individuals, that used two independent cohorts of LC patients. Cohort 1 was from a previous study, while participants in cohort 2 were chosen if they had LC with ME/CFS symptoms. Clinical evaluation involved serial assessments using questionnaires such as the De Paul Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ), FACIT Fatigue scale, and Cognitive Failure Questionnaire (CFQ) Fibromyalgia (FM) diagnosis was based on ACR criteria, using the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and Symptom Severity (SS) scale. The study used peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated for flow cytometry analysis, clinical tests (CBC, CRP, autoantibodies), cytokine and chemokine multiplex analysis, and ELISA assays. Statistical analysis included Wilks-Shapiro test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA | The LC and recovered (R) groups were well-matched in age. Hospitalization rates during acute phase were 22.6% LC vs.16.6% R in cohort 1 and 11.8% LC vs. 11.7 % R in cohort 2. Comorbidities in cohort 1 were 15.9% and 16.6 % for LC and R, respectively. In cohort 2, co-morbidities were 8.8% for LC and 5.8% for R. The odds of females having LC were 3 times higher than males in both cohorts. The study noted that the majority of patients with LC suffered from comorbid fibromyalgia (72.7% in cohort 1 and 67.6% in cohort 2) and cognitive dysfunction. The LC group showed a relative increase in absolute neutrophils and monocytes but a decrease in lymphocyte counts. There was a significant reduction in the absolute number of naïve T cells in the LC cohorts, indicating selective T cell exhaustion with reduced naïve but increased terminal effector T cells. Pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines were significantly elevated in both LC cohorts. LC was associated with elevated levels of plasma pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, Galectin-9 (Gal-9), and artemin (ARTN). The presence of autoantibodies was found in 54.5% of the first LC cohort and approximately 55.8% of the second LC cohort. Multiple regression model revealed an increase in CD4TE, ARTN, CEC, Gal-9, CD8TE, and MCP1, and a decrease in TGF-β1 and MAIT cells that distinguished LC from the recovered group. |

| Fibromyalgia and LC | Zhang et al. [77] | Using microarray data of blood transcriptome from 75 fibromyalgia patients (GSE67311 dataset) and 29 covid-19 patients (GSE177477 dataset), authors sought to identify differential expression among the groups and potential drug targets. Machine learning was used for identifying key diagnostic genes for COVID-related fibromyalgia (LASSO algorithm and random forest in packages of R software) | Pathways of neuroactive ligand receptor interaction, ECM receptor interaction, and calcium signalling were significantly activated in the fibromyalgia group. The authors of the study concluded that these findings provide new evidence for the central sensitization hypothesis. Further analysis linked the differentially expressed genes to multiple various signalling pathways. Some commonality in differentially expressed genes between fibromyalgia and covid-19 was found. A diagnostic nomogram was developed (area under the curve of the receiver operating characteristic was 0.746) but was not validated on a new external sample of patients. |

| Fibromyalgia in rheumatoid arthritis during pandemic | Foti et al. [122,183] | A population of Italian patients diagnosed with pre-existing rheumatological disease (rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or psoriatic arthritis) was screened for fibromyalgia via The Fibromyalgia Rapid Screening Tool questionnaire and assessed for pain, depression, anxiety, and disease impact using questionnaires, during the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic via telemedicine. | High rates of fibromyalgia (21.1% in RA and 24% psoriatic arthritis) were found. Patients with a fibromyalgia positive screening had a higher median RA impact of disease. These figures are similar to those known in literature regarding fibromyalgia’s increased prevalence in RA populations. |

| Fibromyalgia in rheumatoid arthritis patients during pandemic | Upadhyaya et al. [130] | A cross-sectional study aimed to evaluate the rates of depression, anxiety, and fibromyalgia using questionnaires, among a group of RA adult patients in New Delhi, India, between June 2020 and June 2021. Fibromyalgia was assessed using the Polysymptomatic Distress Scale (range 0–31) (as the sum of the WPI and SSS). | 200 patients were included. Comorbid fibromyalgia with RA was associated with more disease activity, less remission, more functional disability, and poorer quality of life. Although it is known that fibromyalgia is more common in populations with rheumatological diseases, the study found that 31% of RA patients had fibromyalgia compared to 4% of the control group, which is higher than the 15-21% prevalence reported in pre-pandemic literature for RA [130]. |

| LC in rheumatoid arthritis patients | Michaud et al. [120] | A study of RA patients with physician-diagnosed RA and self-reported COVID infections evaluated at 6-month intervals. Database used for medical and demographic data. Questionnaires were used to assess depression, anxiety, fibromyalgia, fatigue, pain, and sleep problems. (Congress abstract) | LC in the RA population was found to be associated with severe acute COVID-19, use of antibiotics, more severe RA disease, fibromyalgia prior to infection, other comorbidities, and hospitalization for COVID-19. Pre-existing fibromyalgia was not found to be statistically significant in the multivariate regression model while age, number of infections, pain, and depression were significantly associated with LC. |

| Vaccination | Di Stefano et al. [167] | Due to reports that vaccination might trigger harmful effects on the somatosensory nervous system, the authors investigated the relationship between adverse effects of coronavirus vaccination, quantitative sensory testing (QST), autonomic symptoms, and small fiber pathology on skin biopsy. They recruited adult female patients between January and June of 2022 that experienced generalized sensory symptoms and pain as long-term complications after COVID-19 vaccination (for more than 6 months). Skin biopsy was taken from the distal leg to calculate intraepidermal nerve fibre density according to the European Federation of Neurological Societies and Peripheral Nerve Society guidelines. | 15 female individuals (mean age 48.5 years), most of them had received mRNA vaccine and did not have a previous diagnosis of chronic pain or fibromyalgia, or concomitant peripheral or central nervous system diseases, experienced generalized sensory symptoms and pain and fibromyalgia-type features after vaccination. eleven met diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. Orthostatic intolerance was found in the majority. Nerve conduction studies were unremarkable, and most participants had normal QST. They were also found to have a normal skin biopsy. |

3.4. Central and Peripheral Nervous System Abnormalities

3.5. Generalized Joint Hypermobility

3.6. Studies on Interventions

3.7. Reviews (Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Narrative Reviews)

- Fowler-Davis et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review of studies of interventions for post-viral fatigue [59]. They found a range of treatment modalities that have been studied so far but conclude that more research involving heterogenous populations is needed to properly assess their effectiveness in the context of post-viral fatigue syndromes.

- Cohen and colleagues (2022) published a comprehensive review on the relationship between chronic pain and infections, elaborating on mechanisms that could be relevant to LC-associated pain [92].

- Rao et al. (2022) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis (41 studies, 9,362 patients in total) to evaluate the prevalence and prognosis of post-COVID-19 fatigue [60]. They found that fatigue prevalence was 44.9% (95% CI 0.329 - 0.575, I2 = 70.57%) within the first 3 months post-recovery according to a small number of relevant studies, but substantial differences existed among studies. Female patients, inpatient setting, and individuals recruited through social media and in Europe had a higher prevalence of fatigue.

- A systematic review and meta-analysis by Kerzhner et al. (2024) [124] sought to evaluate rates of LC’s persistent pain manifestations, as well as the impairment to health-related quality of life and data on laboratory inflammatory markers in LC. In their analysis, a substantial level of heterogeneity was found and funnel plots demonstrated considerable asymmetry. The pooled proportion of individuals experiencing general body pain symptoms up to one year after COVID-19 acute phase resolution was found to be higher in the nonhospitalized compared to hospitalized individuals (0.306 vs. 0.089, respectively, I2 = 95%, p(subgroup) = 0.009). They also discuss the increased associations related to young age, females, and less severe acute COVID-19, as well as a progressive temporal-proportional trend instead of the usual subsiding nature of most other symptoms [124]. On that note, Ebbesen et al. witnessed a similar trend in their findings from a nationwide cross-sectional study [105].

- A systematic review and meta-analysis by Hwang et al. (2023) [62] appraised viral infections as an etiology of ME/CFS.

3.8. Findings from Preprints and the Narrative Literature Search of Subtopics

4. Summary and Conclusions

- (1)

-

Etiopathogenesis and theoretical framework: unraveling the underlying pathobiology and disease mechanisms. These crucial knowledge gaps revolve around the fundamental mechanisms that drive fibromyalgia-type clinical features, the role of viral triggering, contribution of dysregulated immune pathways, genetic and epigenetic predisposition, environmental and lifestyle factors, neural mechanisms and their temporal dynamics, and the supposed role of emotional stress. Also, the current evidence concerning the impact of hospitalization history on the incidence of post-COVID fibromyalgia is inconclusive. This ambiguity is likely attributable to methodological inconsistencies, disparate definitions of fibromyalgia and LC, and variations in the selection criteria of study populations.A comprehensive theoretical framework for fibromyalgia (and LC) is needed that goes beyond explanations focused solely on pain and hyperalgesia or fatigue. It should enable robust theory-based predictions and potentially lead to the development of disease-modifying treatments. Common symptoms that are documented as associated with LC include fatigue, low mood, shortness of breath, persistent cough, autonomic symptoms such as postural orthostatic intolerance, cognitive dysfunction, brain fog, sleep difficulties, low grade fever, and joint pain [212,226,252,253,254]. Additional multiorgan manifestations as described in literature are myalgia, headache, chest pain or chest tightness, poor appetite, sicca, diarrhea, dizziness, sweating, alopecia, insomnia, restless legs, nightmares, and lucid dreams [252,255,256,257]. An online survey conducted across multiple countries found that approximately 85% of respondents with persistent illness reported relapses, primarily due to exercise, physical or mental activity, and stress [252].Besides chronic pain, other manifestations of fibromyalgia include easy bruising [27,258], urinary urgency [259], functional gastrointestinal disturbances, sleep disturbances, autonomic symptoms, wheezing, brain fog [27], a reportedly distinct brain pattern on functional magnetic resonance imaging [28,139,260], tingling, creeping or crawling sensations [259], reduced skin innervation [261], close association with gastroesophageal reflux disease [262], various autoantibodies among subgroups of patients [263,264], dry mouth, dry eyes, blurred vision, restless legs, multiple chemical sensitivity, fluid retention, and more [27,44,265]. In a 2023 meta-analysis that included 188,751 patients, an increased standardized mortality (SMR) ratio in fibromyalgia was found for mortality from infections (SMR 1.66, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.38), accidents (SMR 1.95, 95% CI 0.97 to 3.92), and suicide (SMR 3.37, 95% CI 1.52 to 7.50) [266].

- (2)

- Diagnosis and assessment: bridging the gap to objective measures. This includes the need for biomarkers, the standardization of diagnostic criteria, phenotyping, correlation between objective findings and symptom severity, and addressing symptomatic overlap of the related syndromes.

- (3)

- Phenotyping: can help clarify the varied underlying biological mechanisms and facilitate the development of subtype-specific therapies.

- (4)

- Patient experience and coping. This includes, among other things, the consequences of clinician dismissal of symptoms [8], factors associated with late diagnosis, addressing the problem of medical stigma, and factors associated with over/under-diagnosis.

- (5)

- Treatment/rehabilitation and interventions: moving towards effective strategies for treatment, including treatments for addressing specific symptoms (neurological, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, mood, etc.), non-pharmacological treatments, personalized medicine approaches, understanding mechanisms of treatments and how they relate to the pathophysiology, integration of digital therapeutics, and striving for more patient education. Future research into LC interventions shouldn’t neglect the role of a rehabilitative approach for treating LC and fibromyalgia.

- (6)

- Prevention: Need for better knowledge on evidence-based prevention strategies besides the obvious effort of avoiding infection.

- (7)

- Prognosis: Need for better knowledge regarding fibromyalgia and post-COVID fibromyalgia-type syndrome prognosis.

- (8)

- Methodological synchronization and harmonization in the field. As an evolving relatively amorphous field of research there is heterogeneity and inconsistency in fundamental aspects such as definitions, methods, and instruments used. Also, there are still limited systematic reviews, and there is a need for longitudinal studies.

- (9)

- Bridging basic science and clinical research.

- (10)

- Another significant knowledge gap concerns the extent to which clinicians are equipped with contemporary evidence-based knowledge regarding the evolving understanding of LC.

5. Recommendations for Future Research

-

First, accurate assessment of post-COVID symptom trajectories necessitates future research that stratifies analyses by acute phase severity and hospitalization status. An analysis of all patients without making a distinction between severities of COVID-19 can add confounding factors related to hospitalization, antibiotic use, intensive care admission, and cases with well-defined organ damage, which could make it difficult to draw meaning from their results in terms of “LC.” The number of infection episodes, immunization status, behaviour and environmental factors during the initial recovery from the acute phase, and variant type, are also variables that could potentially be relevant to further investigate in the future. During the review process, patient surveys were found that did not corroborate the presence of the outcome being measured prior to acute covid-19, which makes it difficult to infer anything about new-onset or worsening of symptoms, or other self-reported measures.Also, hypermobility syndrome appears to be another confounding factor that should be taken into account in future epidemiological studies of LC, as this seems to be an important variable for the phenomenon. It is important to emphasize that undiagnosed fibromyalgia and/or GJH may contribute to the development of LC but are frequently overlooked in the clinical setting. This can add confounding to studies that make use of official diagnostic codes and criteria for fibromyalgia. Due to the high cut-off set by the ACR criteria, the absence of fibromyalgia diagnosis, taken as an indicator for absence of fibromyalgia syndrome, may not suffice for choosing controls. For example, an individual with chronic widespread pain and somatic symptom severity score of 4 (that is, not eligible for official fibromyalgia diagnosis) in the control group could confound the results, as the cut-off chosen for fibromyalgia diagnosis by the ACR seems to be biologically arbitrary.

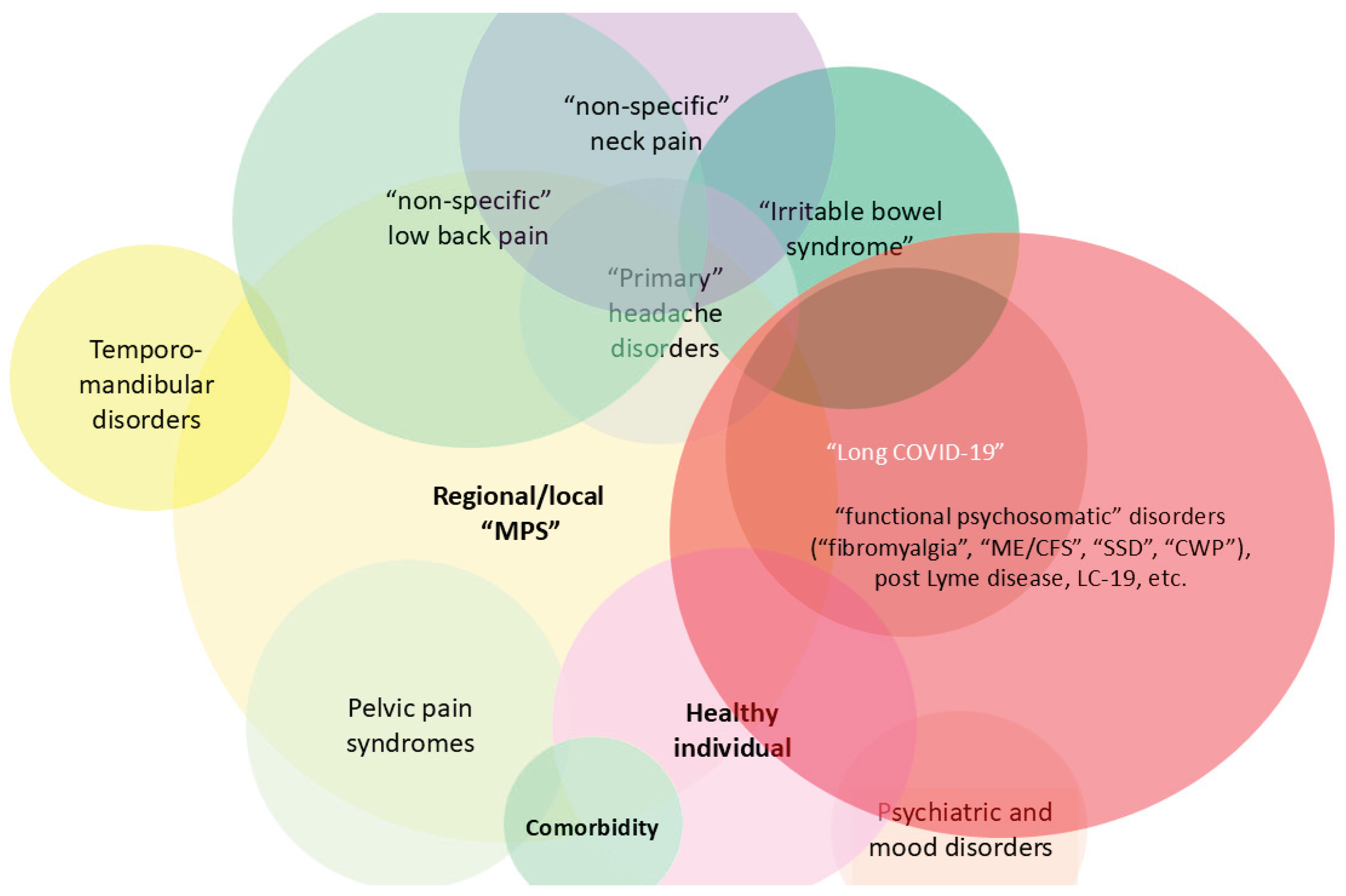

- Secondly, in studies using diagnostic criteria or diagnostic codes that distinguish functional psychosomatic syndromes, the investigator should recognize that making a distinction between chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia diagnosis (and even ME/CFS), or ignoring their overlap, may confound results if the mechanism is shared, as has been suggested by some authors [43,64]. Moreover, researchers conducting a correlation analysis between variables or outcome measures that represent overlapping constructs such as stress and fibromyalgia diagnosis or chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia-type symptoms, or CSI score and depression [108,120,243,267], will end up with results that seem redundant unless that is what the study was designed to do.

- Third, it’s worth noting that studies that recognize central sensitization as a phenomenon simply based on hypersensitivity in the palmar side of the participants’ dominant hand, for example [112], do not necessarily relate to a mechanism of nociplastic generalized central pain augmentation and sensory hypersensitivity. If the authors of a study conclude that generalized central hypersensitivity and allodynia were found, then they might like to demonstrate that it is, indeed, both central and generalized. A methodological issue [29]was evident in literature in relation to the “central sensitization inventory” questionnaire, which tries to capture the impact of chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia [268] or “fibromyalgia-type features.” Authors have mistaken the CSI for central sensitization [111,115,117,139,184].

- A multifaceted etiology.

- Overlap between LC, chronic fatigue syndrome, related functional somatic syndromes and fibromyalgia symptomatology (including multiple medically unexplained multisystemic refractory symptoms, widespread myofascial discomfort and myofascial pain, hyperalgesia, itching, fatigue, post-exertional malaise, POT syndrome and autonomic symptoms, morning stiffness, spasms, irritable bowel, multiple chemical sensitivity, and more)

- Multisystem non-specific clinical findings (subclinical inflammation and immune dysregulation, metabolic abnormalities, low-grade hypoxia, muscle histopathological abnormalities, intraepidermal small fibre pathology, etc.)

- Unremarkable results on routine medical tests.

- The risk factors.

- Significant association with both hypermobility syndrome and low vitamin D.

- A relatively high prevalence of LC in mild and subclinical acute disease cases among previously healthy individuals.

- Insidious and heterogenous nature of the condition.

- Pain varying in anatomical location, and neuroanatomically illogical distributions.

- Other anomalies and counterinstances such as discrepancies between empirical findings and expected findings in nerve conduction studies and pressure pain threshold measurements, dissociation between measures of sensitization and subjective burden [249], low correlations between disease burden and conditioned pain modulation [269], autoantibodies and inconsistent findings regarding them [263,270], evidence of peripheral neuropathy in subgroups, disappointing and poor response to theory-based pharmacotherapies, symptomatic response to weather change [271], discordance between autonomic small fiber pathology and autonomic symptoms [272], and more [248,249,250].

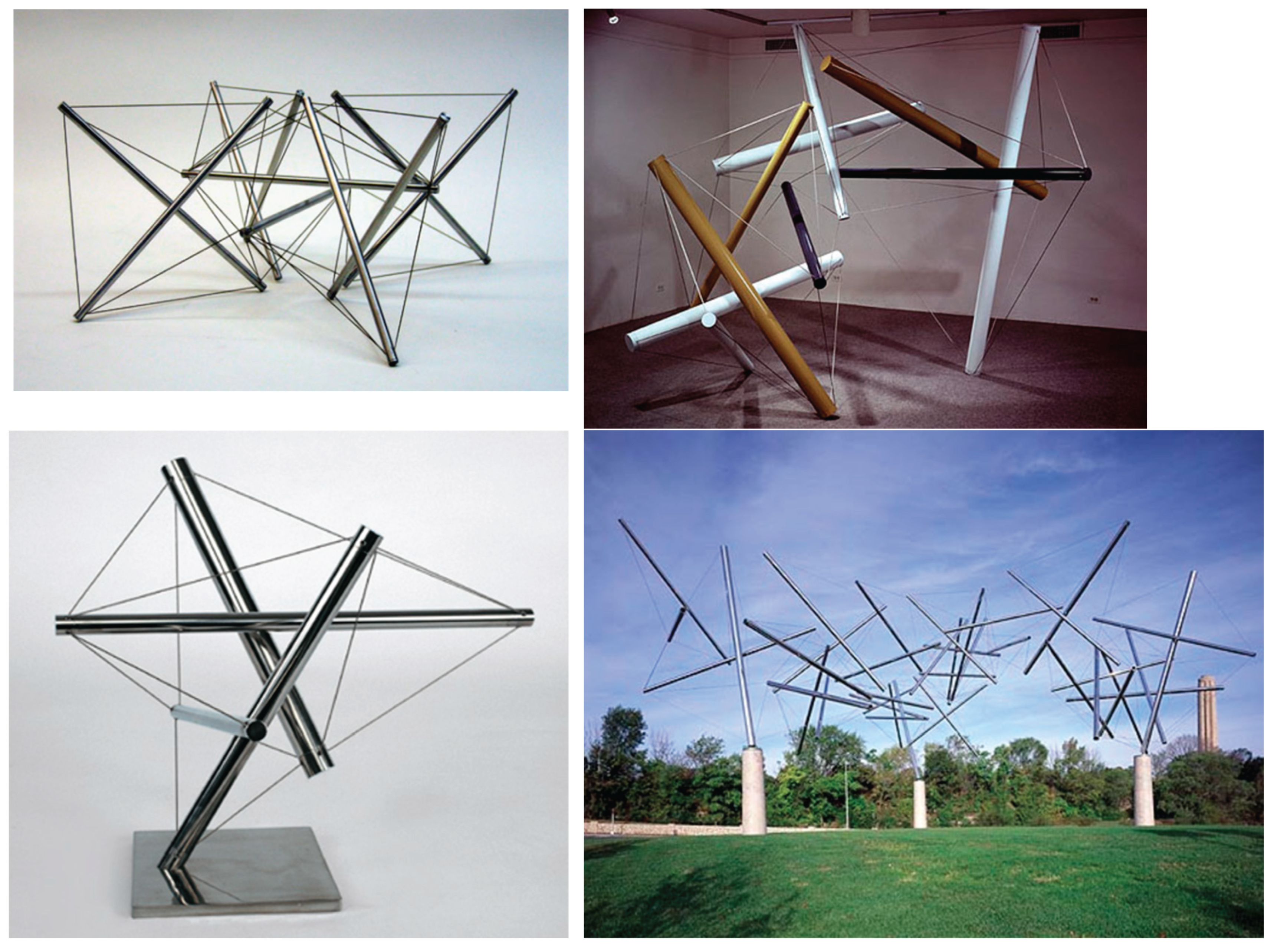

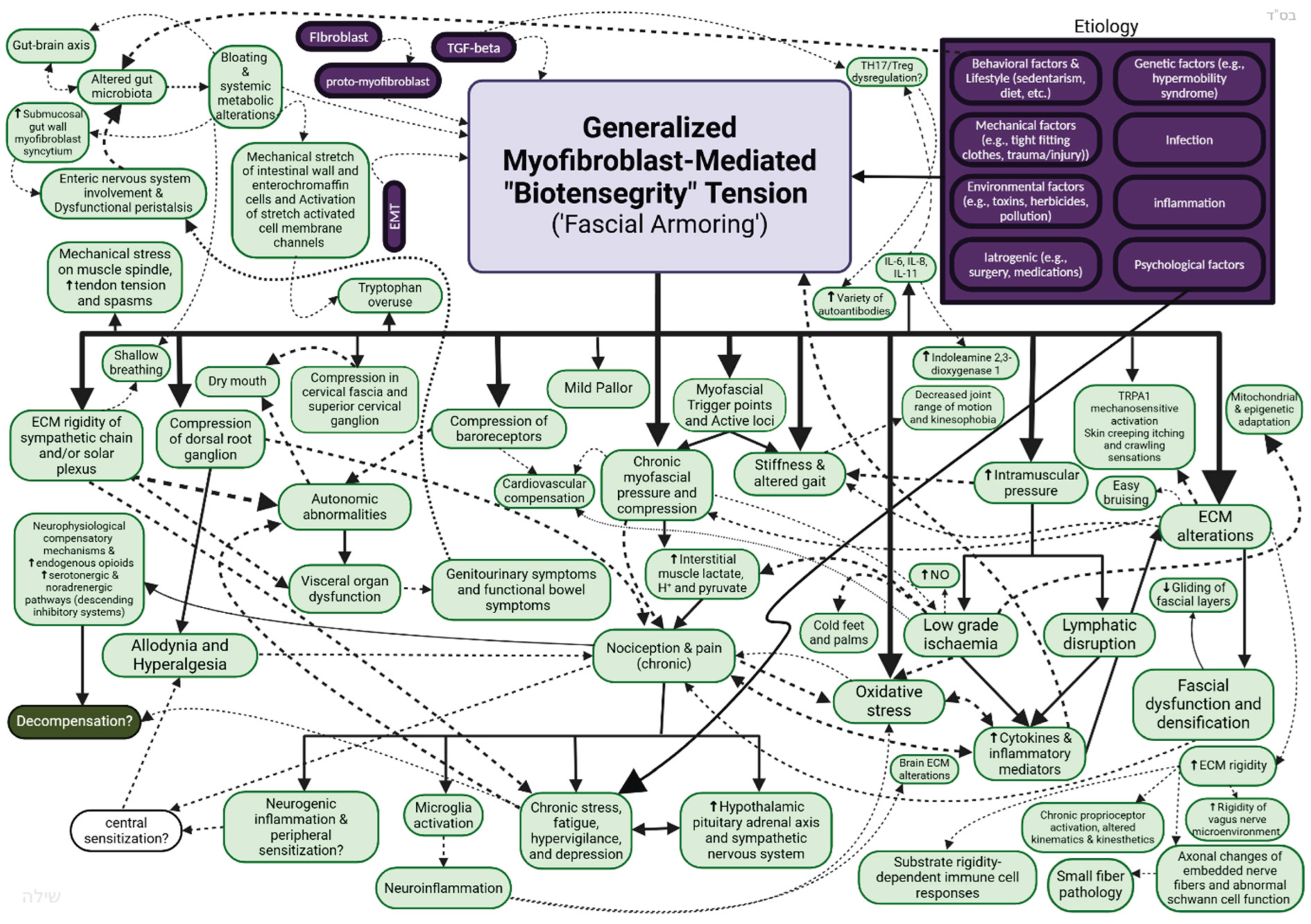

6. Part Two– Synthesis of Data and Formulating a Mechanism for “Fibromyalgia Syndrome” Pathophysiology

6.1. Fascial Armouring: A Conceptual Framework for the Etiopathogenesis and Cellular Pathway of ‘Primary Fibromyalgia Syndrome’

- (i)

- Normal mechanobiology of myofibroblasts

- (ii)

- Tensegrity qualities when superimposed on the interconnectedness of the fascio-musculo-skeletal system

- (iii)

- Myofascial chains

- (iv)

- Innervation and sensory functions of fascia

- (v)

- Substrate stiffness & rigidity of ECM

6.2.“. Fascial Armoring” as a Fascio-Musculoskeletal Medical Entity of Continuum Biomechanics

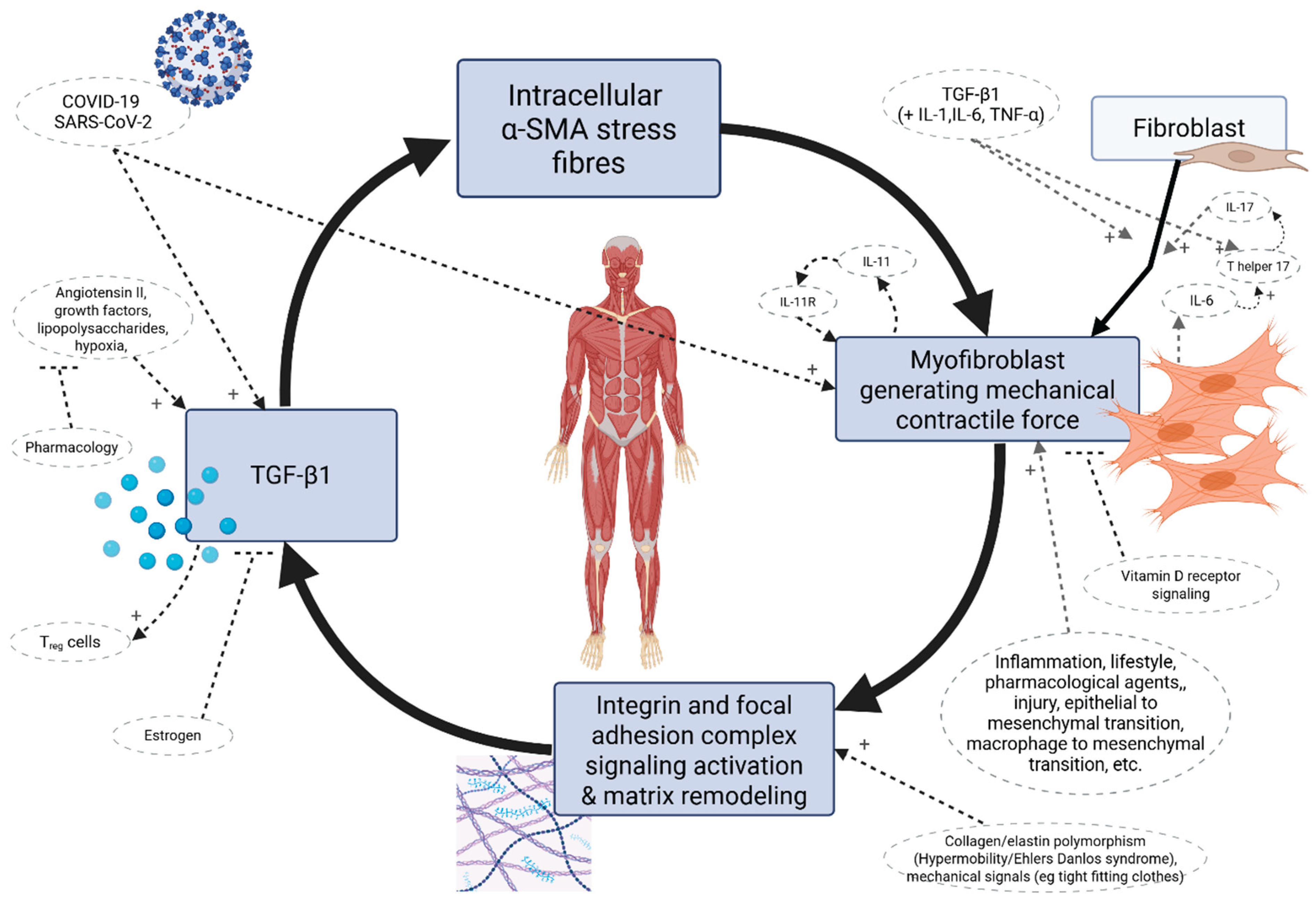

6.3. Soft Tissue Myofibroblasts in the Context of COVID-19

7. Interpreting LC Manifestations and Drawing Theory-Based Predictions

7.1. Mechanistic Predictions of 'Long COVID-19' Manifestations Based on the Suggested Biomechanical Model

- Hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: Collagen microarchitecture affects mechanosensitive signaling in cells followed by an induction of myofibroblasts and secretion of proangiogenic factors (vascular endothelial growth factor and IL-8) when studied in human adipose-derived stem cell culture [435]. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is associated with ECM disarray and increased myofibroblast phenotype when studied in vitro [436]. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorders are probably not separate entities but rather appear to be both on a continuum characterized by altered ECM homeostasis and a chronic inflammatory state [436]. If ECM microarchitecture augments myofibroblast activity in patients with hypermobility syndrome, it is mainly for this reason that GJH is expected to increase their risk for fibromyalgia-type symptoms, a relationship that should be weakly explained statistically by psychological stress levels alone [290].

- Mechanical tension on the skin has been shown to enhance myofibroblast activity [437]. The application of mechanical forces such as by use of splints further corroborates this finding [438]. The development of myofascial pain is linked to tight-fitting clothes [290,439,440]. Tight-fitting clothes and accessories are expected to predispose individuals to fibromyalgia due to input into the integrin-mediated yes-associated protein cascade of myofibroblast mechano-activity.

- Lifestyle and exercise (movement): Though not performed on myofascial tissue in vivo, a study showed that cyclical mechanical stretch reduces myofibroblast differentiation of primary lung fibroblasts [441]. Tissue stretch reduces TGF-β1 and type-1 procollagen in mouse subcutaneous connective tissue [442]. Immobility leads to fibrosis and an increase in myofibroblasts in knee joint capsule when studied in vivo [443]. Immobility allows for the development of abnormal cross linking between connective tissue fibres [444]. These findings provide, in general, the biological rationales for the role of exercise (movement) versus sedentarism according to the suggested myofascial-based mechanism. It is interesting in this respect that yoga involves cyclical stretching of almost all body parts as an integral aspect of the practice.

- The effect of taking hot showers during the acute induction phase of myofibroblasts following infection, and the long-term effect of a possible activation of heat shock proteins in a subcutaneous population of myofibroblast requires further investigation. It is not necessarily expected to be inert.

- The effect of weather changes on symptoms will be facilitated by the biophysical effects of temperature, electromagnetics and humidity on myofascial tissue and hyaluronic acid.

- If factors such as tattoo ink or smoking induce subcutaneous myofibroblasts, sedentary people with whole-body tattoos and smokers are expected to have worse and more prolonged psychosomatic symptoms after covid-19. A similar link is expected for those using cosmetics and topical creams containing substances that upregulate pathways of subcutaneous fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation.

- Diet and the gut brain axis [446] fit in the mechanism of LC from multiple angles and not only in relation to connective tissue.

- Obesity: in obesity, connective-tissue fibrosis is induced and mediated by mechano-transducing signaling pathways [447]. Fibrotic processes mediated by myofibroblasts can transform the mechanical properties of subcutaneous tissue, increasing its rigidity and connective tissue stiffness [447]. For this reason, obesity is predicted to be a significant risk factor for LC.

- Hair loss: adipocyte to myofibroblast transition is a possible cause of alopecia [448]. The connective tissue sheath and follicular papilla can use gap junctions to form a communicating network. During hair cycling, this network plays a part in the control of hair follicle dynamic structural changes [449]. Hair loss is therefore expected to occur and be weakly explained by psychological stress levels.

- Pallor: might be an overlooked manifestation, reflecting impaired peripheral perfusion due to autonomic and non-autonomic or hydrostatic causes.

- Explaining Morning stiffness: Tomasek et al. (2002) [291] describe the dynamics of fibroblast populations in three-dimensional collagen lattices and the process of generating traction and tension in their surrounding matrix of collagen fibrils. Over several hours the forces increase until a plateau is reached. If a similar process occurs in fascia in vivo, then a period of immobility would be comparable to this process of allowing the cells to reach the plateau of a higher tension state uninterrupted.

- (Fascio)Musculoskeletal: altered pendulousness of the legs. If the physician is searching for an objective mechanism-based sign of the disease to test bedside, this might be a relatively good one.

- Cardiovascular: A mild chronic compartment-like syndrome affecting multiple muscles should, by a chronic contraction of skeletal muscles, impair perfusion and lymph flow and alter starling forces which could exacerbate pre-existing subclinical cardiovascular issues. The typical presentation would, by reasoning, include changes in blood pressure regulation, fatigue on exertion or after a heavy meal, palpitations, higher resting heart rate, cold feet and palms, sub/clinical impairment of sexual function, and absence/impairment of morning erection in males, due to impaired blood flow to various organs. Chronic compressive forces in the periorbital fascia would lead to subclinical reduced optic disc perfusion. Idiopathic fluid retention might also be derived mechanistically.

- Active loci: possibly due to mechanical stress on the muscle spindles as well as sympathetic overactivity. Tonic slow adapting receptors in nuclear chain fibers of the muscle spindle would activate gamma motoneurons via the stretch reflex in prestressed myofascial tissue. Also, afferent input from gastrocnemius-soleus muscle C-fibres produces long-lasting excitability of the biceps femoris/semitendinosus α-motoneuron efferent fibers through the flexion reflex in an animal model [450]. A mechanistic discussion of myofascial pain syndrome and active loci in the context of this framework is available in a recent study [290].

- Immune system: based on a finding that substrate stiffness affects immune cell function [398]. Fibroblasts and inflammatory myofibroblasts secrete cytokines as part of their natural activity [295]. An overactive (or “irritable”) state of immune cells due to paracrine proinflammatory cytokine secretion, chronic low-grade inflammation, and increased substrate rigidity of the ECM would likely predispose the immune system to over-reacting in intolerance to “irritant” antigens. Such immune hyperirritability could be evident in the form of predisposition to gluten intolerance, multiple chemical sensitivity, association with autoinflammatory reactions, or other clinical or subclinical immune dysregulation. Fibromyalgia and LC are associated with mast cell dysregulation [451]. A mechanistic explanation, among several, can be related to findings [452] that tissue stiffness affects mast cell behavior and function.

- Metabolism: Myofibroblasts secrete IL-6, IL-8, and IL-11 [295,401]. The cytokine IL-6, besides its effect on CD4+ T lymphocytes, can activate indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, as shown in different cell types [84,453,454], and therefore is potentially intimately related to the metabolic balance of the tryptophan-indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1-kynurenine and serotonin pathway. Metabolites of this pathway (e.g., the neurotoxic metabolite quinolinic acid) [455], some of which can cross the blood brain barrier [456], were observed in altered systemic levels in fibromyalgia [457,458], and are linked to cognitive impairment and depression [84]. Besides cytokines, the gut microbiome has the capacity to modulate indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 too, for example via butyrate production [84,459].

- Mood and psychosomatic disorders: post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression are known manifestations of 'long COVID-19' [460]. “Post-traumatic stress disorder” in this framework (not only in the context of LC) is expected to have a bio-mechanical aspect involving the (fascio)musculoskeletal system. Any acute sympathetic or inflammatory reaction which leads to a simultaneous abrupt contraction of multiple muscles and of the osteomyofascial tensegrity structure would cause a sudden shift in its biomechanical and energetic elastic state. The energetic shift and the mechanical tension locked in the ECM by contracting cells would lead to an increase in widespread tension in the body irrespective of alpha motoneurons. Sympathetic nerve fibers embedded in fascia would also be affected, which is a relevant interface with emotion and cognition. If the musculoskeletal tension is not released after this acute event, overtime fascia and ECM will be remodeled in this higher-tension state which initially was supposed to be a temporary sympathetic defensive reaction. This is followed by myo/fibroblasts remodeling the ECM and stress shielding themselves to mask the tension while, importantly, they form “supermature” focal adhesions and upregulated expression of α-SMA. In their resolution phase, the balance of proliferative and apoptotic signals is crucial for the outcome of myofibroblast cells [296]. They can either undergo apoptosis (mediated by fibroblast growth factor 1, prostaglandin E2, and IL-1beta), evade apoptosis and persist in the tissue, or enter senescence (mediated by CCN1 with upregulated intracellular p16 and p21, and characterized by the acquisition of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype, specifically the secretion of TGF-β1 and pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-6, CCL2, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-8, PDGF, and ECM proteins), or other possible fates [296]. Myofibroblasts become much more active above a certain threshold of matrix rigidity [461]. Higher ECM pre-stress in the tensegrity-like structure crosses the threshold for myofibroblast activity and propels their cascade of mechanobiology and stress shielding, but once fascia is remodeled this way, it is much more difficult to resolve. Fibromyalgia does not typically erupt in patients overnight. The systemic implications aren't limited to myofascial tissue, and include changes in metabolism and secretory profile of myofascial cells, changes in vasculature, effects on the immune system, and more. Interestingly, circulating systemic fibroblast growth factors can deeply affect brain physiology [462]. Also, the intracranial ECM is suggested to be implicated in the pathophysiology of stress-induced depression [463].

- Overlap with “myofascial pain syndromes”: The clinical overlap of myofascial pain and associated psychosomatic and "non-specific" pain conditions (or “central sensitizations symptoms”) is likely to be evident in relation to LC. Figure 7 illustrates in general the clinical overlap reflected by the mechanistic overlap, as suggested by this conceptual framework (not all relationships are depicted in this scheme).

7.2. Predictions of Results on Investigations and Means for Testing the Hypotheses