Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Triggering Immune Response—An infection-induced immune response acts as the initial trigger, with B cells, plasma cells, and autoantibodies playing a role in the underlying pathology.

- Vascular and Autoantibody-Mediated Dysfunction—Autoantibodies, particularly those targeting GPCRs, may affect the vascular system, leading to endothelial dysfunction, impaired neurovascular control, and autonomic small nerve fiber involvement. These autoantibodies—whether pathogenic IgGs or functional autoantibodies that persist beyond the usual resolution—disrupt homeostasis. This disturbance manifests as endothelial dysfunction in both large and small arteries, impaired venous return, preload failure, and arteriovenous shunting, ultimately contributing to blood flow dysregulation and exertion-induced tissue hypoxia.

- Secondary Compensatory Mechanisms—In response, the body adopts compensatory adaptations, including increased sympathetic tone and metabolic shifts aimed at maintaining energy supply. These adaptations further shape the clinical presentation and symptomatology of ME/CFS.

-

Interfere with the pathological immune response:

- with B-cell depletion therapy (anti-CD20 antibody)

- use of cytotoxic drugs (cyclophosphamide)

- modulate the plasma cell survival factors (Anti BAFF antibody)

- Plasma cell inhibition (Anti-CD38 antibody, proteasome inhibition)

- or through Immunoglobulin manipulation (neonatal fragment crystallizable receptor (FcRn) targeting, immunoadsorption, IVIG)

- Address the vascular dysregulation: endothelial dysfunction, arteriovenous shunting, impaired autoregulation (plasmapheresis had been proven to improve endothelial dysfunction in critically ill patients with Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [12])

- Support the patient’s compensatory adaptation by pacing therapy [13], acetylcholinesterase inhibition or cognitive techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Study Procedure and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Patient Selection

- Reasons for IVIG-administration

- Plasma exchange for removing micro-clots

4.2. Data Collection and Patient Compliance

4.3. Subjective Experience of Patients

4.4. Vascular Access

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 6MWT | 6-minute walk test |

| ACTH | adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| AT1-R | angiotensin-1 receptor |

| CO | carbon monoxide |

| CRH | corticotropin releasing hormone |

| CT | computed tomography |

| DIC | Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| EBV | Epstein-Barr virus |

| EQ-5D-5L | European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 Level Version |

| ETA-R-AAB | Endothelin-1 type A receptor antibody |

| FcRn | neonatal fragment crystallizable receptor |

| FSS | Fatigue Severity Scale |

| GPCRs | G protein-coupled receptors |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IGF-2 | Insulin-like growth factor 2 |

| ISI | Insomnia Severity Index |

| IVIG | intravenous immunoglobulin |

| LMM | linear mixed-effects models |

| ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |

| MLM | multilevel model |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| PCS | Long-Covid / post-COVID-19 Syndrome |

| PE | plasmapheresis/ plasma exchange |

| PEM | post-exertional malaise |

| POTS | postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SNRIs | Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| SSRIs | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| alpha1/2-AdR-AAB | anti-adrenergic α1/2 receptor antibody |

Appendix A

| 1. | Outpatient Clinic of Department of Internal Medicine Consultation of Long COVID |

Relevant laboratory results:β1-adrenergic receptor antibody, β2-adrenergic receptor antibody, M3-muscarinic acetylcholine-receptor-antibody, M4-muscarinic acetylcholine-receptor-antibody, Standardized tests Schellong test, 6MWT with Borg-Score, echocardiography, pulmonal functional tests, psychiatric evaluation, EQ-5D-5L Health VAS, EQ-5D-5L, HADS Anxiety, HADS Depression, ISI, FSS, IES-R If the detected autoantibodies showed a relevant elevation, the patients had been assigned to the apheresis consultation. |

| 2. | Consultation Apheresis at the Clinic of Nephrology and Transplant Medicine | The patients were informed about all side effects and complications of the plasma exchange and albumin application. |

| 3. | 1st plasma exchange | Clinical visit Nephrology |

| 4. | 2nd plasma exchange after 5 days | Clinical visit Nephrology |

| 5. | Back to Consultation of Long COVID within 2 weeks | Clinical visit and standardized tests Internal Medicine |

| 6. | 3rd plasma exchange after 1 month | Clinical visit Nephrology |

| 7. | Back to Consultation of Long COVID within 8 weeks | Clinical visit and standardized tests Internal Medicine |

| 8. | 4th plasma exchange after 1 month | Clinical visit Nephrology |

| 9. | Back to Consultation of Long COVID within 2 weeks | Clinical visit, laboratory and standardized tests, follow up |

| Outcome | Questionnaire / reference | Score building / range / cut-off / (sub)scale |

| Insomnia | ISI (Insomnia Severity Index) [20,21] | Sum score / 0 to 28 / ≥ 15 / global |

| Fatigue | FSS (Fatigue Severity Scale) / [22,23] | Sum score / 9 to 63 / ≥ 36 / global |

| Depression and anxiety | HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) / [24,25] | Sum score / 0 to 21 / ≥ 8 / depression Sum score / 0 to 21 / ≥ 8 / anxiety |

| Health-related quality of life | EQ-5D-5L (European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 Level Version) / [26] | Visual analogue scale score / 0 to 100 / no cut-off / current health Index score / -0.59 to 1 / no cut-off / Quality of life consisting of five dimensions; mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression |

References

- E. Stein u. a., „Observational Study of Repeat Immunoadsorption (RIA) in Post-COVID ME/CFS Patients with Elevated ß2-Adrenergic Receptor Autoantibodies—An Interim Report“, J. Clin. Med., Bd. 12, Nr. 19, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Scheibenbogen u. a., „Fighting Post-COVID and ME/CFS—development of curative therapies“, Front. Med., Bd. 10, S. 1194754, Juni 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ø. Fluge, K. J. Tronstad, und O. Mella, „Pathomechanisms and possible interventions in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)“, J. Clin. Invest., Bd. 131, Nr. 14, S. e150377. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Sandvik u. a., „Endothelial dysfunction in ME/CFS patients“, PloS One, Bd. 18, Nr. 2, S. e0280942, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Zawilska und K. Kuczyńska, „Psychiatric and neurological complications of long COVID“, J. Psychiatr. Res., Bd. 156, S. 349–360, Dez. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Wong und D. J. Weitzer, „Long COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)—A Systemic Review and Comparison of Clinical Presentation and Symptomatology“, Medicina (Mex.), Bd. 57, Nr. 5, S. 418, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Morita u. a., „Phase-dependent trends in the prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) related to long COVID: A criteria-based retrospective study in Japan“, PLOS ONE, Bd. 19, Nr. 12, S. e0315385, Dez. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Komaroff und W. I. Lipkin, „ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: road map to the literature“, Front. Med., Bd. 10, S. 1187163, Juni 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Freitag u. a., „Autoantibodies to Vasoregulative G-Protein-Coupled Receptors Correlate with Symptom Severity, Autonomic Dysfunction and Disability in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome“, J. Clin. Med., Bd. 10, Nr. 16, S. 3675, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Szewczykowski u. a., „Long COVID: Association of Functional Autoantibodies against G-Protein-Coupled Receptors with an Impaired Retinal Microcirculation“, Int. J. Mol. Sci., Bd. 23, Nr. 13, S. 7209, Juni 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kruger u. a., „Proteomics of fibrin amyloid microclots in long COVID/post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) shows many entrapped pro-inflammatory molecules that may also contribute to a failed fibrinolytic system“, Cardiovasc. Diabetol., Bd. 21, Nr. 1, S. 190, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Weng, M. Chen, D. Fang, D. Liu, R. Guo, und S. Yang, „Therapeutic Plasma Exchange Protects Patients with Sepsis-Associated Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation by Improving Endothelial Function“, Clin. Appl. Thromb. Off. J. Int. Acad. Clin. Appl. Thromb., Bd. 27, S. 10760296211053313, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. E. M. Sanal-Hayes u. a., „A scoping review of ‚Pacing‘ for management of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): lessons learned for the long COVID pandemic“, J. Transl. Med., Bd. 21, Nr. 1, S. 720, Okt. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Fox u. a., „Plasmapheresis to remove amyloid fibrin(ogen) particles for treating the post-COVID-19 condition“, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., Bd. 7, Nr. 7, S. CD015775, Juli 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Cervantes, E. M. Bloch, und C. J. Sperati, „Therapeutic Plasma Exchange: Core Curriculum 2023“, Am. J. Kidney Dis., Bd. 81, Nr. 4, S. 475–492, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Kiprov u. a., „Case Report: Therapeutic and immunomodulatory effects of plasmapheresis in long-haul COVID“, F1000Research, Bd. 10, S. 1189, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Nunes, M. Vlok, A. Proal, D. B. Kell, und E. Pretorius, „Data-independent LC-MS/MS analysis of ME/CFS plasma reveals a dysregulated coagulation system, endothelial dysfunction, downregulation of complement machinery“, Cardiovasc. Diabetol., Bd. 23, Nr. 1, S. 254, Juli 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. B. Arumugham und A. Rayi, „Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)“, in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. Zugegriffen: 22. Januar 2025. [Online]. Verfügbar unter: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554446/.

- „EQ-5D-5LUserguide-23-07.pdf“. Zugegriffen: 16. Februar 2025. [Online]. Verfügbar unter: https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/EQ-5D-5LUserguide-23-07.pdf.

- C. M. Morin u. a., „Effect of Psychological and Medication Therapies for Insomnia on Daytime Functions: A Randomized Clinical Trial“, JAMA Netw. Open, Bd. 6, Nr. 12, S. e2349638, Dez. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dieck, C. M. Morin, und J. Backhaus, „A German version of the Insomnia Severity Index: Validation and identification of a cut-off to detect insomnia“, Somnologie, Bd. 22, Nr. 1, Art. Nr. 1, März 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. B. Krupp, „The Fatigue Severity Scale: Application to Patients With Multiple Sclerosis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus“, Arch. Neurol., Bd. 46, Nr. 10, Art. Nr. 10, Okt. 1989. [CrossRef]

- P. O. Valko, C. L. Bassetti, K. E. Bloch, U. Held, und C. R. Baumann, „Validation of the Fatigue Severity Scale in a Swiss Cohort“, Sleep, Bd. 31, Nr. 11, Art. Nr. 11, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Zigmond und R. P. Snaith, „The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale“, Acta Psychiatr. Scand., Bd. 67, Nr. 6, Art. Nr. 6, Juni 1983. [CrossRef]

- Petermann, „Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Deutsche Version (HADS-D)“, Z. Für Psychiatr. Psychol. Psychother., Bd. 59, Nr. 3, Art. Nr. 3, Juli 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Herdman u. a., „Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L)“, Qual. Life Res., Bd. 20, Nr. 10, Art. Nr. 10, Dez. 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. Green und C. J. MacLeod, „SIMR : an R package for power analysis of generalized linear mixed models by simulation“, Methods Ecol. Evol., Bd. 7, Nr. 4, Art. Nr. 4, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Stein u. a., „Efficacy of repeated immunoadsorption in patients with post-COVID myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and elevated β2-adrenergic receptor autoantibodies: a prospective cohort study“, Lancet Reg. Health - Eur., Bd. 49, S. 101161, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Hendrix u. a., „Adrenergic dysfunction in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis“, Eur. J. Clin. Invest., Bd. 55, Nr. 1, Art. Nr. 1, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Cocks und D. J. Torgerson, „Sample size calculations for pilot randomized trials: a confidence interval approach“, J. Clin. Epidemiol., Bd. 66, Nr. 2, S. 197–201, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Team R. Core. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Online: http://www. R-project. org. 2013;201. .

- M. Templ, A. Kowarik, A. Alfons, G. De Cillia, und W. Rannetbauer, „VIM: Visualization and Imputation of Missing Values“. S. 6.2.2, 11. Oktober 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. V. Buuren und K. Groothuis-Oudshoorn, „mice : Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R“, J. Stat. Softw., Bd. 45, Nr. 3, Art. Nr. 3, 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. B. Rubin und N. Schenker, „Multiple imputation in health-are databases: An overview and some applications“, Stat. Med., Bd. 10, Nr. 4, Art. Nr. 4, Apr. 1991. [CrossRef]

- Field, Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics, 6th edition. Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Melbourne: Sage, 2024.

- D. W. Bates, S. Saria, L. Ohno-Machado, A. Shah, und G. Escobar, „Big data in health care: using analytics to identify and manage high-risk and high-cost patients“, Health Aff. Proj. Hope, Bd. 33, Nr. 7, S. 1123–1131, Juli 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Armstrong, „When to use the B onferroni correction“, Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt., Bd. 34, Nr. 5, Art. Nr. 5, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Warnes u. a., „gplots: Various R Programming Tools for Plotting Data“. S. 3.2.0, 30. Mai 2005. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, „ggplot2“, WIREs Comput. Stat., Bd. 3, Nr. 2, Art. Nr. 2, März 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. Morton und J. S. Nijjar, „eq5d: Methods for Analysing ‚EQ-5D‘ Data and Calculating ‚EQ-5D‘ Index Scores“. S. 0.15.6, 22. Mai 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Ludwig, J.-M. Graf von der Schulenburg, und W. Greiner, „German Value Set for the EQ-5D-5L“, PharmacoEconomics, Bd. 36, Nr. 6, S. 663–674, Juni 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Barahona Afonso und C. M. P. João, „The Production Processes and Biological Effects of Intravenous Immunoglobulin“, Biomolecules, Bd. 6, Nr. 1, S. 15, März 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Ludwig u. a., „Mechanisms of Autoantibody-Induced Pathology“, Front. Immunol., Bd. 8, S. 603, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Xu u. a., „Modulation of endothelial cell function by normal polyspecific human intravenous immunoglobulins: a possible mechanism of action in vascular diseases“, Am. J. Pathol., Bd. 153, Nr. 4, S. 1257–1266, Okt. 1998. [CrossRef]

- E. Pretorius u. a., „Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin“, Cardiovasc. Diabetol., Bd. 20, Nr. 1, S. 172, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

| Main symptom by category | ME/CFS | PCS |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive impairment | attention, reaction time, which worsens after physical/cognitive exertion | memory, attention, executive functions |

| cerebral hypometabolism | up to 10 months* | |

| reduced cerebral blood flow | reduced cerebral blood flow (up to 10 months post-infection) | |

| Hypothalamic-pituitary growth hormon abnormalities | reduced peripheral CRH, ACTH, cortisol and IGF1 and IGF2 levels* | reduced peripheral CRH, ACTH, cortisol and IGF1 and IGF2 levels* |

| Autonomic dysfunction | a variety of autonomic testing showed impairments, autonomic dysfunction correlates with symptom severity* | similar findings to ME/CFS-group |

| Pain | lowered treshold | central sensitisation possible |

| small fiber neuropathy | ||

| Sleep disturbances | insomnia, non-restorative sleep*, irregular sleep patterns | chronic insomnia, hypersomnia, irregular sleep patterns |

| Autoantibodies | anti-adrenergic α1 receptor antibody (gastrointestinal symptoms)[9] anti-adrenergic α2- receptor antibody (gastrointestinal symptoms)[9] Mas-receptor antibody against angiotensin-II T1 receptor Endothelin-1 type A receptor antibody (cognitive impairment)[9] |

anti-adrenergic α1 receptor antibody [10] anti-adrenergic β2 receptor antibody [10] Mas-R antibody against angiotensin-II T1 receptor [10] |

| Clotting abnormalities | microclots, hyperactivated platelets | fibrin amyloid microclots, with entrapped pro-inflamatory molecules ↓ plasma Kallikrein, ↑ platelet factor 4,, ↑ von Willebrand factor, marginally increased level of α-2 antiplasmin [11] |

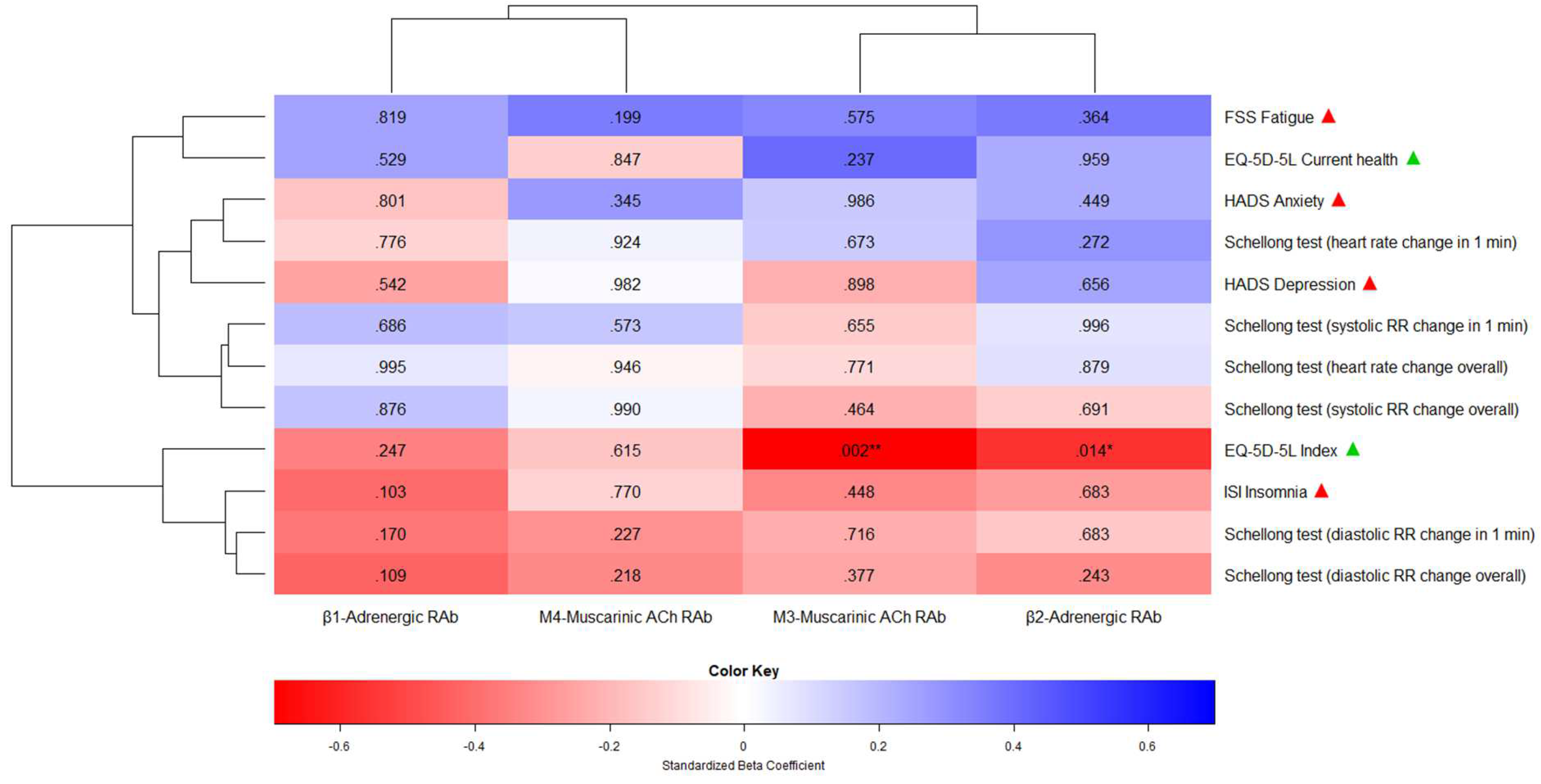

| Independ. variable / predictor | Depend. variable / endpoint | Point estimate | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | Std. error | T-stat. | Degrees of freedom | P-val. | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β1-Adrenergic Receptor Antibody | ISI Insomnia | -0.30 | -0.67 | 0.06 | 0.19 | -1.63 | 2910.66 | .103 | 0.17 |

| FSS Fatigue | 0.16 | -1.31 | 1.63 | 0.70 | 0.23 | 17.10 | .819 | 0.04 | |

| HADS Anxiety | -0.03 | -0.30 | 0.23 | 0.14 | -0.25 | 86.63 | .801 | 0.02 | |

| HADS Depression | -0.11 | -0.47 | 0.25 | 0.18 | -0.61 | 64.73 | .542 | 0.06 | |

| EQ-5D-5L Index | -0.01 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -1.16 | 156.69 | .247 | 0.12 | |

| EQ-5D-5L Current health | 0.39 | -0.84 | 1.62 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 52.83 | .529 | 0.06 | |

| Schellong test | |||||||||

| Heart rate change (1 min) |

-0.20 | -1.57 | 1.17 | 0.70 | -0.28 | 424.78 | .776 | 0.01 | |

| Heart rate change (overall) | 0.004 | -1.32 | 1.33 | 0.67 | 0.01 | 1300.64 | .995 | 0.003 | |

| Systolic RR change (1 min) |

0.11 | -0.41 | 0.62 | 0.26 | 0.41 | 106.71 | .686 | 0.03 | |

| Systolic RR change (overall) | 0.06 | -0.71 | 0.83 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 68.47 | .876 | 0.02 | |

| Diastolic RR change (1 min) | -0.07 | -0.45 | 0.31 | 0.16 | -0.42 | 7.30 | .683 | 0.06 | |

| Diastolic RR change (overall) | 0.44 | -0.66 | 1.54 | 0.44 | 0.99 | 5.75 | .364 | 0.09 | |

| β2-Adrenergic Receptor Antibody | ISI Insomnia | -0.07 | -0.45 | 0.31 | 0.16 | -0.42 | 7.30 | .683 | 0.06 |

| FSS Fatigue | 0.44 | -0.66 | 1.54 | 0.44 | 0.99 | 5.75 | .364 | 0.09 | |

| HADS Anxiety | 0.06 | -0.10 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 72.77 | .449 | 0.05 | |

| HADS Depression | 0.06 | -0.21 | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.46 | 12.24 | .656 | 0.04 | |

| EQ-5D-5L Index | -0.01 | -0.02 | -0.002 | 0.003 | -2.46 | 504.26 | .014* | 0.32 | |

| EQ-5D-5L Current health | 0.02 | -0.99 | 1.04 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 15.92 | .959 | 0.04 | |

| Schellong test | |||||||||

| Heart rate change (1 min) |

0.49 | -0.39 | 1.38 | 0.45 | 1.10 | 147.33 | .272 | 0.08 | |

| Heart rate change (overall) | 0.07 | -0.87 | 1.01 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 685.47 | .879 | 0.01 | |

| Systolic RR change (1 min) |

0.00 | -0.34 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 763.25 | .996 | 0.004 | |

| Systolic RR change (overall) | -0.09 | -0.54 | 0.36 | 0.23 | -0.40 | 342.55 | .691 | 0.02 | |

| Diastolic RR change (1 min) | -0.05 | -0.28 | 0.19 | 0.11 | -0.41 | 26.13 | .683 | 0.02 | |

| Diastolic RR change (overall) | -0.28 | -0.75 | 0.19 | 0.24 | -1.17 | 312.92 | .243 | 0.11 | |

| M3-Muscarinic Acetyl-choline Receptor Antibody | ISI Insomnia | -0.18 | -0.72 | 0.35 | 0.23 | -0.80 | 7.23 | .448 | 0.09 |

| FSS Fatigue | 0.43 | -1.34 | 2.21 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 6.40 | .575 | 0.06 | |

| HADS Anxiety | 0.00 | -0.27 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 48.48 | .986 | 0.01 | |

| HADS Depression | -0.02 | -0.40 | 0.35 | 0.18 | -0.13 | 17.53 | .898 | 0.03 | |

| EQ-5D-5L Index | -0.02 | -0.02 | -0.01 | 0.01 | -3.17 | 110.29 | .002** | 0.46 | |

| EQ-5D-5L Current health | 0.72 | -0.50 | 1.94 | 0.60 | 1.21 | 30.06 | .237 | 0.15 | |

| Schellong test | |||||||||

| Heart rate change (1 min) | 0.29 | -1.07 | 1.66 | 0.70 | 0.42 | 322.16 | .673 | 0.02 | |

| Heart rate change (overall) | -0.20 | -1.57 | 1.17 | 0.70 | -0.29 | 822.55 | .771 | 0.01 | |

| Systolic RR change (1 min) | -0.11 | -0.60 | 0.38 | 0.25 | -0.45 | 635.23 | .655 | 0.02 | |

| Systolic RR change (overall) | -0.25 | -0.91 | 0.41 | 0.33 | -0.73 | 249.11 | .464 | 0.04 | |

| Diastolic RR change (1 min) | -0.08 | -0.55 | 0.39 | 0.21 | -0.37 | 10.23 | .716 | 0.04 | |

| Diastolic RR change (overall) | -0.31 | -0.99 | 0.38 | 0.35 | -0.88 | 503.73 | .377 | 0.06 | |

| M4-Muscarinic Acetyl-choline Receptor Antibody | ISI Insomnia | -0.08 | -0.61 | 0.45 | 0.27 | -0.29 | 216.60 | .770 | 0.01 |

| FSS Fatigue | 0.90 | -0.48 | 2.28 | 0.69 | 1.30 | 68.50 | .199 | 0.10 | |

| HADS Anxiety | 0.15 | -0.17 | 0.47 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 411.64 | .345 | 0.08 | |

| HADS Depression | 0.01 | -0.40 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 155263.9 | .982 | 0.0003 | |

| EQ-5D-5L Index | -0.004 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -0.50 | 585.01 | .615 | 0.03 | |

| EQ-5D-5L Current health | -0.15 | -1.63 | 1.34 | 0.75 | -0.19 | 180.80 | .847 | 0.01 | |

| Schellong test | |||||||||

| Heart rate change (1 min) |

0.09 | -1.70 | 1.87 | 0.91 | 0.10 | 96242.33 | .924 | 0.001 | |

| Heart rate change (overall) | -0.06 | -1.80 | 1.68 | 0.89 | -0.07 | 23644.78 | .946 | 0.001 | |

| Systolic RR change (1 min) |

0.17 | -0.43 | 0.78 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 905826.11 | .573 | 0.03 | |

| Systolic RR change (overall) | 0.01 | -0.88 | 0.90 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 40299.40 | .990 | 0.001 | |

| Diastolic RR change (1 min) | -0.30 | -0.78 | 0.19 | 0.25 | -1.21 | 609.36 | .227 | 0.10 | |

| Diastolic RR change (overall) | -0.51 | -1.33 | 0.30 | 0.42 | -1.23 | 9418.34 | .218 | 0.11 |

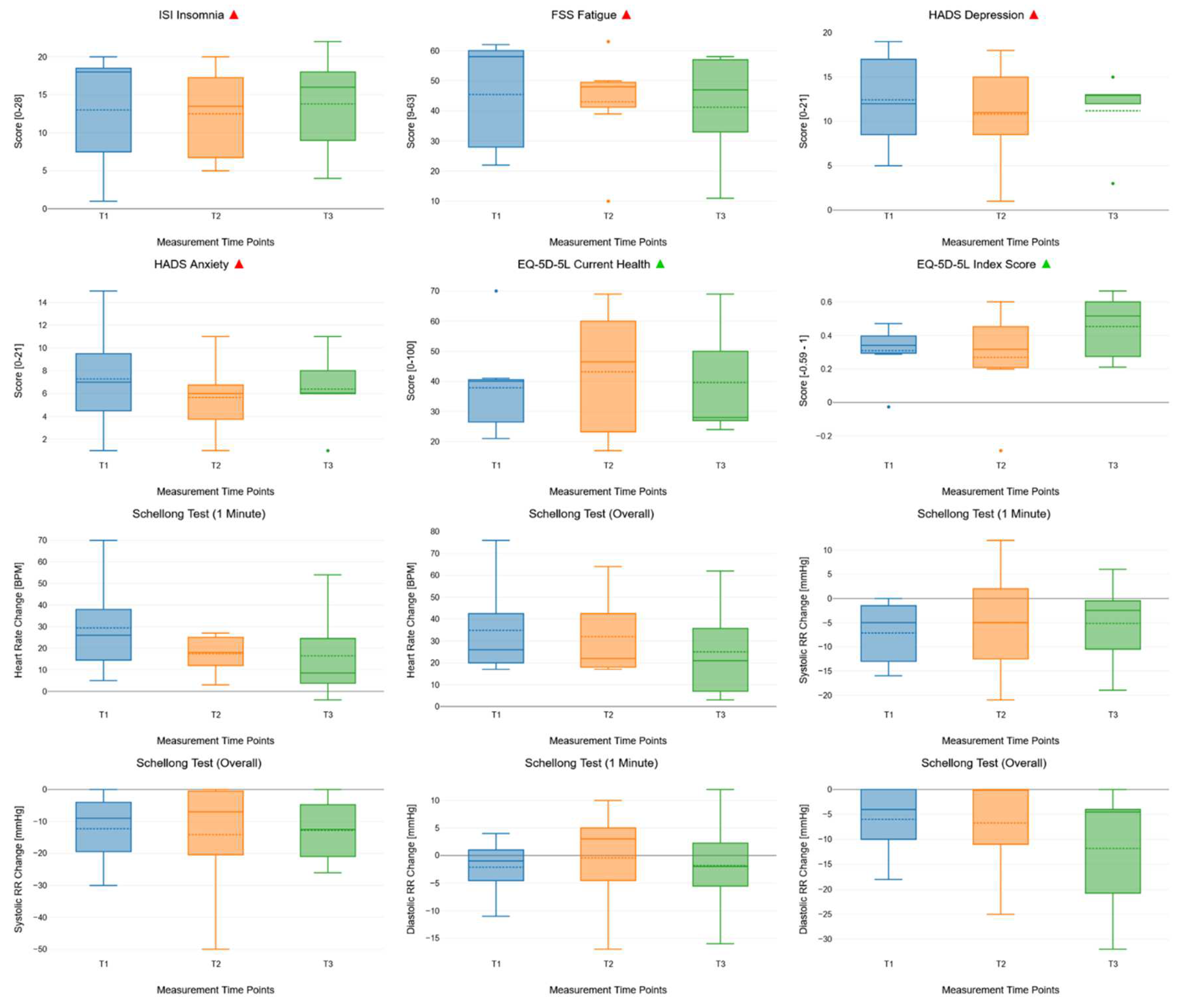

| Outcome | Effect | Degrees of freedom (nom.) | Degrees of freedom (denom.) | Mauchly’s test of sphericity | F | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISI | Time | 2 | 13.44 | Equal variances | 0.2 | 0.818 | 0.03 |

| Insomnia | |||||||

| FSS | Time | 2 | 24.43 | Equal variances | 0.41 | 0.667 | 0.04 |

| Fatigue | |||||||

| HADS | Time | 2 | 49.56 | Equal variances | 0.48 | 0.621 | 0.03 |

| Depression | |||||||

| HADS | Time | 2 | 293.17 | Equal variances | 0.65 | 0.521 | 0.04 |

| Anxiety | |||||||

| EQ-5D-5L | Time | 2 | 26.89 | Equal variances | 0.38 | 0.686 | 0.05 |

| Current health | |||||||

| Schellong test | |||||||

| Heart rate change | Time | 2 | 216.16 | Equal variances | 1.84 | 0.162 | 0.12 |

| (1 min) | |||||||

| Systolic RR change | Time | 2 | 198.57 | Equal variances | 0.16 | 0.853 | 0.02 |

| (1 min) | |||||||

| Systolic RR change (overall) | Time | 2 | 612.6 | Equal variances | 0.06 | 0.945 | 0.01 |

| Diastolic RR change | Time | 2 | 64.26 | Equal variances | 0.36 | 0.698 | 0.01 |

| (1 min) | |||||||

| Diastolic RR change (overall) | Time | 2 | 1232.92 | Equal variances | 1.59 | 0.204 | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).