1. Introduction

In December 2019, Wuhan, China, saw a surge in pneumonia cases that spread globally. Due to their similarity to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 [

1] virus, these cases were attributed to a new virus, SARS-CoV-2. Since then, around 770 million cases and over 7 million deaths have been confirmed.[

2] The World Health Organization defines Long-COVID (LC) as the persistence or emergence of new symptoms lasting more than three months after the initial infection, with no apparent cause.[

3] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes LC as a range of new, returning, or ongoing health issues that last more than four weeks after a person has been infected with SARS-CoV-2.[

4]

In the United States, survey data indicate that approximately 7% of adults have experienced LC, impacting millions globally.[

5] Initially, symptoms like cognitive impairment, neuromuscular issues, depression, and fatigue were attributed to post-intensive care syndrome. However, this theory faced challenges when similar symptoms arose in tens of thousands of patients from the pandemic's first wave, many of whom had mild symptoms and never required hospitalization.[

5]

LC is a multifactorial condition characterized by debilitating new or persistent symptoms, including post-exertional malaise (PEM), fatigue, and cognitive impairment ("

brain fog"). Pathological features in LC, such as changes in the immune, cardiovascular, metabolic, gastrointestinal, nervous, and autonomic systems, overlap with those of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Given current evidence, many LC patients may eventually meet the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS.[

6,

7]

ME/CFS is primarily characterized by PEM, severe fatigue, cognitive impairment, unrefreshing sleep, myalgia, polyarthralgia, headache, and autonomic dysfunction, all of which significantly affect daily life.[

8,

9,

10] The potential link to LC is widely speculated, as not all LC patients meet the criteria for ME/CFS.[

8] Symptoms, such as PEM, fatigue, and sleep disturbances in LC may also result from viral infections, known as post-viral fatigue syndrome (PVFS). Given these overlaps, it's unsurprising that LC symptoms may either represent an isolated condition or align with PVFS or ME/CFS.[

11]

LC and ME/CFS share significant overlaps in symptoms and underlying mechanisms. These similarities are so pronounced that many researchers now hypothesize that LC may serve as a trigger for ME/CFS in susceptible individuals or might even represent a post-viral subset within the broader ME/CFS spectrum.

Several criteria exist for diagnosing ME/CFS. The Fukuda criteria [

12], used for many years, omit some common symptoms. The more recent International Consensus Criteria (ICC) [

8], based on the Canadian Consensus Criteria, offer a more comprehensive approach by emphasizing the condition's multi-system nature and removing the 6-month symptom duration requirement, which addresses these gaps.

The aim was to apply the ICC criteria [

8] to a group of subjects without known SARS-CoV-2 infection and compare it with two groups of SARS-CoV-2 patients: one without symptoms and the other with new or persistent symptoms after 6 months.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and Patients

From July 2021 to June 2024, we randomly selected and evaluated adult control subjects and patients of both sexes from our medical school and teaching hospital. Patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection were divided into two gender-balanced groups: the LC-no (asymptomatic) group and the LC-yes group (with persistent or new symptoms six months after the acute infection). Inclusion criteria required a symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test or the presence of antibodies. Exclusion criteria for the patients included: (a) ICU admission for ventilatory support, (b) a history of neuromuscular diseases, (c) prior persistent fatigue, and (d) chronic systemic conditions such as diabetes or chronic kidney disease.

2.2. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Score

ME/CFS was diagnosed according to the ICC [

8] (

Table 1) if the individual experienced PEM (domain A) and showed at least one symptom from each of the domains B, C, and D. The severity of PEM was evaluated by scoring the five subcategories (

Table 1) as follows: (0) no symptoms, (1) occasionally, (2) about half the time, (3) most of the time, and (4) continuous symptoms. The ICC [

8] aids in identifying severe cases of ME/CFS by outlining the clinical benchmarks used to assess fatigue, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairments, and dysfunctions in the autonomic nervous, neuroendocrine, and immune systems.

As this study investigated a medical condition (ME/CFS) that lacks a definitive biological marker, it relied on structured questionnaires based on the ICC.[

8] To ensure consistency and accuracy, all interviews were conducted in person by the same researcher (one of the authors, CRG). Each interview took place in a comfortable setting, lasted approximately 30 minutes, and followed a standardized set of questions that were applied uniformly across all participant groups. The interviewer ensured that each participant clearly understood the questions before responding. All participants had an educational level sufficient to comprehend and accurately answer the questionnaire.

2.3. Clinical Summary

Thirteen symptoms of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection were documented, including fever, cough, sore throat, runny nose, shortness of breath, phlegm, muscle pain, tiredness, fatigue, headache, diarrhea, and loss of smell and taste.

Tiredness is a nonspecific term that refers to a subjective feeling of lacking energy or experiencing exhaustion. It can stem from various physiological, psychological, or environmental causes. Fatigue is a persistent and subjective sensation of physical, mental, or emotional exhaustion that is disproportionate to recent activity and is not relieved by rest. Unlike tiredness, it often indicates an underlying medical, psychological, or physiological condition. However, in clinical anamnesis, it appears to be the same. We consider fatigue when there is no relief from rest.

2.4. Statistics

Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data and as the median and percentiles for non-normally distributed data. Normality was assessed using the Anderson-Darling, D'Agostino-Pearson, Shapiro-Wilk, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. For variable comparisons: (1) the parametric unpaired Student's t-test was used for normally distributed variables; (2) the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was applied for non-normally distributed variables; (3) Z-scores were calculated for two population proportions. All comparison tests were conducted with a 95% confidence interval. Statistical analysis was performed using Minitab® Statistical Software (State College, Pennsylvania, USA).

3. Results

The mean age of the 37 adult control subjects, representing both sexes, was 40.9 years. For the 32 patients matched by sex, the mean age was 36.6 years for the LC-no group (16 cases) and 42.4 years for the LC-yes group (16 cases). The mean body mass index was 27.3 in the control group, 27.6 in the LC-no group, and 28.7 in the LC-yes group. The average time between SARS-CoV-2 acute infection and the interview was 11.9 months for the LC-no group (ranging from 6 to 24 months) and 15.5 months for the LC-yes group (ranging from 7 to 29 months).

During the acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, the most frequently reported symptoms were tiredness (75%), loss of taste (68.8%), fatigue (62.5%), loss of smell (59.4%), headache (56.3%), fever (46.9%), cough (43.8%), myalgia (43.8%), sore throat (37.5%), dyspnea (34.4%), rhinorrhea (28.1%), and diarrhea (25%). Notably, no patients reported phlegm. Tiredness and/or fatigue were reported by 93.7% of the LC-yes group, compared to 62.5% in the LC-no group. Additionally, 68.8% of individuals in the LC-yes group experienced six or more symptoms during the acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared to only 31.3% in the LC-no group. A Z-test for two population proportions yielded a p-value of 0.034, indicating statistical significance (p < 0.05).

SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by PCR test in 87.5% of cases and by antibodies in 12.5%. Regular daily medications were used by 50% of the control group, 25% of the LC-no group, and 45.3% of the LC-yes group. However, no evidence was found to suggest that the use of these medications affected the ICC [

8] score.

Table 2 presents the ICC [

8] scores for all groups. ME/CFS was diagnosed in 10.8% of the control group (with a 3:1 female-to-male ratio), 6.7% of the LC-no group (all female), and 18.8% of the LC-yes group (all male). The symptoms are listed in order of frequency, from most to least common. No significant differences were observed in the rates of ME/CFS diagnosis among the groups.

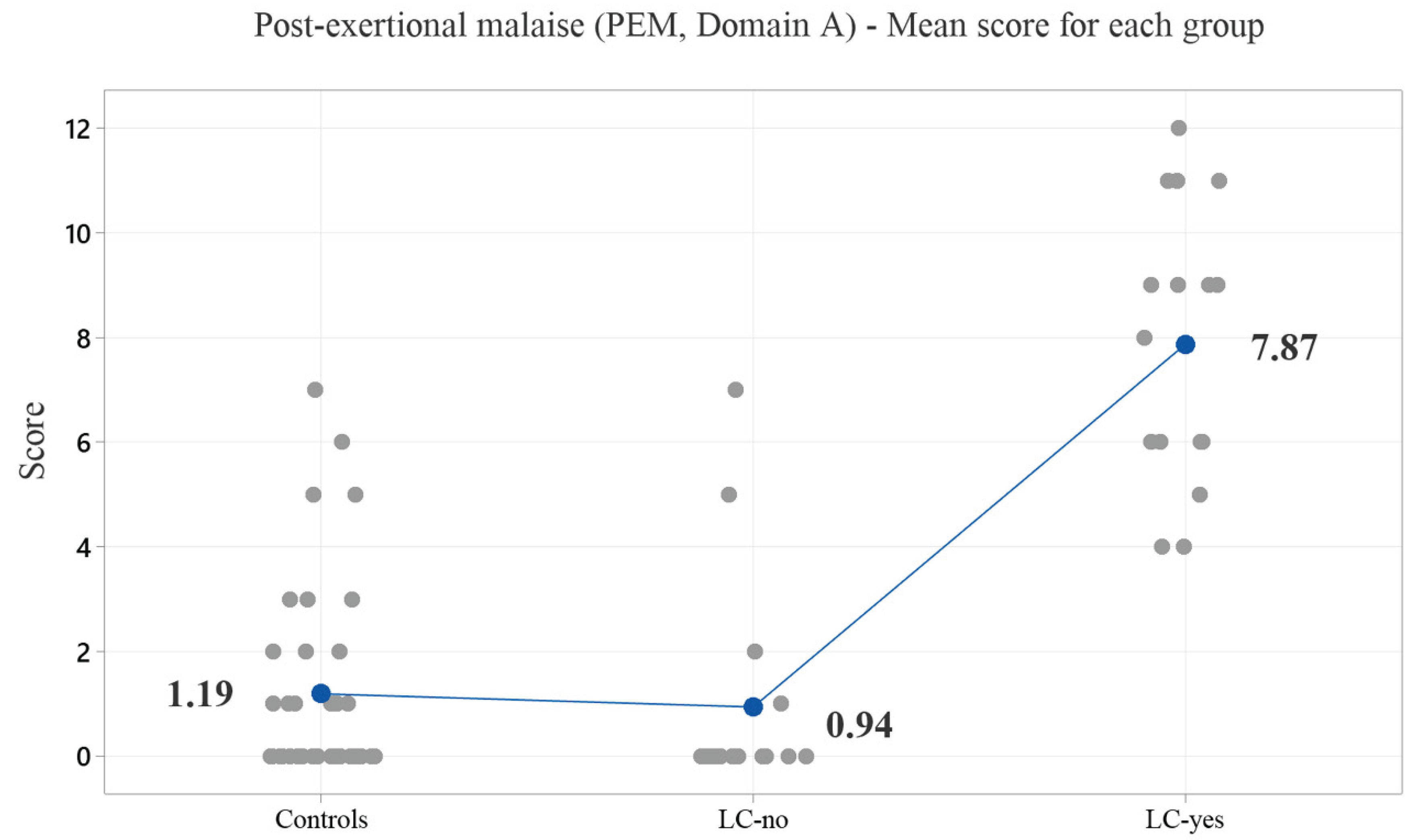

Figure 1 illustrates the average symptom scores across the five PEM subcategories.

4. Discussion

4.1. Our Findings

The mean time between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the ICC [

8] assessment was over six months for both COVID groups. PEM was reported in 100% of the LC-yes group and 25% of the LC-no group. The mean scores for the five domain A subcategories were 1.19 for the control group, 0.94 for the LC-no group, and 7.94 for the LC-yes group, with the LC-yes group showing a highly significant difference (p = 0.000) compared to the other groups. PEM, neurosensory/perceptual/motor disturbances, neurocognitive impairments, sleep disturbances, pain, and loss of thermoregulatory stability were present in over 50% of the LC-yes group, which differed significantly from the LC-no group (

Table 2). The time that elapsed between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the interview for completing the ME/CFS questionnaire varied slightly among participants, but this did not affect the results. All individuals with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection responded clearly and without any uncertainty regarding the type, duration, intensity, and sequence of their symptoms. In the LC-yes group, the majority of individuals continued to experience the same symptoms that were present during the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as fatigue. In a smaller proportion of cases, new symptoms that were not present during the acute phase emerged, such as PEM or sleep disturbances. These symptoms could not be explained by any underlying medical condition. Since SARS-CoV-2 infection was a global public health issue (pandemic), the likelihood that a control subject—i.e., someone without a history of acute infection—had been infected was minimal. During that period, any flu-like symptoms were investigated with high suspicion, and they were rarely forgotten within just a few months, so no bias was registered. None of the cases exhibited indicators of severe disease during the acute infection, as evidenced by the absence of hospital stays exceeding one day for routine evaluations for acute flu-like illness. As outlined in the methods, no cases were included if the individual required admission to an intensive care unit for ventilatory support.

ME/CFS was diagnosed in 10.8% of the control group (four individuals), 6.7% of the LC-no group (one female), and 18.8% of the LC-yes group (three males). No significant differences were found in ME/CFS diagnosis rates among the groups. A notable finding that supports the distinction between LC and ME/CFS is the presence of expected epidemiological patterns for ME/CFS in the control group—that is, individuals without a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In these cases, the female-to-male ratio was 3:1, consistent with what is reported in the literature.[

13,

14,

15] However, in the group with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistent symptoms lasting more than six months, this pattern was not observed, suggesting distinct pathophysiological processes and potentially separate clinical entities for LC.

The most commonly reported symptoms during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection included tiredness (75%), loss of taste (68.8%), and fatigue (62.5%). In the LC-yes group, 87.5% reported fatigue and/or tiredness, compared to only 37.5% in the LC-no group. Additionally, 68.8% of individuals in the LC-yes group experienced six or more symptoms during their acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, while only 31.3% in the LC-no group did. This comparison suggests that the number of symptoms experienced during the acute phase may be a potential risk factor for developing LC.

4.2. Long-COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

ME/CFS and LC may present with similar symptoms [

16], but there is no consensus on the percentage of LC cases that meet the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS.[

9,

13,

17,

18,

19] ME/CFS is diagnosed when symptoms meet the ICC criteria[

8] and cannot be attributed to other clinical or psychiatric conditions.[

8,

9] Reports of LC fulfilling the ME/CFS diagnostic criteria vary widely, with figures ranging from as low as 5% to as high as 56.8% of patients months after SARS-CoV-2 infection.[

4,

18,

20] This wide variation could be explained by outdated diagnostic criteria, such as the Fukuda criteria, [

12] which do not account for many central nervous system dysfunctions. As a result, this can artificially increase the number of LC cases diagnosed with ME/CFS.[

21] Data analysis of 739 patients revealed only an 8.4% prevalence of ME/CFS among LC patients, with those infected during the Omicron phase showing a significantly lower prevalence of ME/CFS.[

22] Similarly, Tokumasu et al.[

19] found that 17.9% of LC cases were diagnosed with ME/CFS, which aligns closely with our findings of 18.8%.

4.3. Long-COVID

Regardless of the ME/CFS diagnosis, fatigue is the most common symptom of LC, affecting 50% to 70% of patients [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], and it is likely of central origin.[

28] This fatigue is often associated with "

brain fog," characterized by memory problems, lack of mental clarity, poor concentration, and an inability to focus.[

29] Other common symptoms include cough, dyspnea, sleep disturbances, adjustment disorders, headache, anosmia/ageusia, difficulty concentrating, memory loss, confusion, arthralgia, and cognitive impairments.[

13,

16,

23,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] In Latin America, the prevalence of LC has been estimated at 47.8%, with individuals reporting symptoms three months after contracting SARS-CoV-2 infection.[

34] In Brazil, a telephone-based survey in São Paulo, among hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, estimated the prevalence of LC at 47.1% and 49.5%, respectively.[

36] A Canadian study of 88 hospitalized patients found that 66.7% experienced fatigue three months after infection, with the rate dropping to 59.5% after six months.[

7] The overall pooled prevalence of LC among hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients is 43%, with higher rates in hospitalized patients (54%) compared to non-hospitalized individuals (34%). Additionally, females are more frequently affected than males (49% vs. 37%).[

37] Notably, the development of LC does not appear to be strictly correlated with the severity of the initial illness or the patient's age.[

3,

31,

38] Risk factors for LC include female sex, repeated infections, and more severe initial infection.[

5]

4.4. Fatigue

Although various muscle pathological abnormalities have been suggested as potential causes of LC myalgia and fatigue [

25], clinical inflammatory myopathy—characterized by limb-girdle weakness, dysphagia, and neck weakness—is rarely observed in LC cases. Given that millions of people experience LC symptoms, we face challenges in explaining it as a pathological muscle abnormality in any condition that presents with myalgia and fatigue. In a cohort of COVID-19 patients with mild to moderate acute symptoms, skeletal muscle injury—defined by elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels (>200 IU/L) and clinical score—was observed in 22.4% of cases.[

39] Their findings were primarily based on clinical presentation and serum CK levels, without incorporating needle electromyography, muscle biopsy, or muscle-specific antibodies for a more comprehensive evaluation. This limitation hampers the ability to differentiate muscle injury from acute post-viral syndromes or peripheral neuropathy. It is also important to note that both LC and ME/CFS patients may experience sensory or autonomic small-fiber neuropathy,[

40] which can manifest as impaired heat detection and increased tortuosity of tiny fibers in the central corneal subbasal plexus.[

10] However, these characteristics do not provide distinct diagnostic criteria to differentiate between LC patients and those with ME/CFS unrelated to LC. A recent study found normal values for isolated muscle fiber conduction velocity

in situ and jitter parameters in the

Tibialis Anterior muscle in cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection, both with and without LC-related fatigue.[

28] This suggests that fatigue may be more accurately attributed to the central nervous system (CNS). Central fatigue occurs when the CNS reduces its ability to activate or sustain muscle contractions. As found in our previous study, [

28] while jitter and muscle fiber conduction velocity tests showed no dysfunction at the neuromuscular junction or within the muscle fibers themselves, researchers argue that fatigue may originate centrally, meaning the CNS is not sending strong enough signals to maintain muscle performance.

4.5. Limitations

Several limitations should be considered: 1. The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the results. 2. While both controls and patients on medication were included, the proportions were similar across groups, with the LC-yes group using fewer medications than the control group. 3. Evaluating any potential long-term improvement in symptoms following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 was not within the scope of this study; however, it could theoretically shorten the duration of LC symptoms.

5. Conclusions

Many symptoms (six or more) during the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection appear to contribute to the development of LC. In most cases, LC-related PEM persists from the acute infection phase rather than emerging as a new symptom. The most common symptoms of LC include PEM, neurosensory, perceptual, or motor disturbances, cognitive impairments, sleep disturbances, pain, loss of thermoregulatory stability, and flu-like symptoms, with significant differences compared to other groups. In the LC-yes group, PEM was present in 100% of cases. Yet, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), as defined by the ICC [

8], was diagnosed in only 18.8%. These findings suggest that ME/CFS may not be the most appropriate diagnosis for most LC cases.

Author Contributions

J.A.K. and C.R.G. designed the study; C.R.G. and L.A.R.Y. assisted with patient interviews, data extraction, and preliminary analysis. J.A.K. performed the primary statistical analysis. J.A.K. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors reviewed the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil, supported this work (grant number 2022/02291-1 to J.A.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and approved by the ethics committee of the Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil, under the number 4904517, where the tests were performed.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's findings are openly available in the Data Center of the Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and can be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R. et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Feb 20;382(8):727-733. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Yong, S.J. Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect. Dis. (Lond). 2021 Oct;53(10):737-754. [CrossRef]

- Nikolich, J.Ž.; Rosen, C.J. Toward Comprehensive Care for Long Covid. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023 Jun 8;388(23):2113-2115. [CrossRef]

- Ely, E.W.; Brown, L.M.; Fineberg, H.V. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Committee on Examining the Working Definition for Long Covid. Long Covid Defined. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024 Nov 7;391(18):1746-1753. [CrossRef]

- Sukocheva, O.A.; Maksoud, R.; Beeraka, N.M.; Madhunapantula, S.V.; Sinelnikov, M.; Nikolenko, V.N.; Neganova, M.E.; Klochkov, S.G.; Amjad, K.M.; Staines, D.R. et al. Analysis of post COVID-19 condition and its overlap with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Adv. Res. 2022 Sep;40:179-196. [CrossRef]

- Magel, T.; Meagher, E.; Boulter, T.; Albert, A.; Tsai, M.; Muñoz, C.; Carlsten, C.; Johnston, J.; Wong, A.W.; Shah, A. et al. Fatigue presentation, severity, and related outcomes in a prospective cohort following post-COVID-19 hospitalization in British Columbia, Canada. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 2023 Jun 29;10:1179783. [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, B.M.; van de Sande, M.I.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Broderick, G., Mitchell, T.; Staines, D.; Powles, A.C.; Speight, N.; Vallings, R. et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J. Intern. Med. 2011 Oct;270(4):327-38. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. Epub 2011 Aug 22. Erratum in: J Intern Med. 2017 Oct;282(4):353. [CrossRef]

- Twomey, R.; DeMars, J.; Franklin, K.; Culos-Reed, S.N.; Weatherald, J.; Wrightson, J.G. Chronic Fatigue and Postexertional Malaise in People Living With Long COVID: An Observational Study. Phys. Ther. 2022 Apr 1;102(4):pzac005. [CrossRef]

- Azcue, N.; Teijeira-Portas, S.; Tijero-Merino, B.; Acera, M.; Fernández-Valle, T.; Ayala, U.; Barrenechea, M.; Murueta-Goyena, A.; Lafuente, J.V.; de Munain, A.L. et al. R Small fiber neuropathy in the post-COVID condition and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Clinical significance and diagnostic challenges. Eur. J. Neurol. 2025 Feb;32(2):e70016. [CrossRef]

- Westermeier, F.; Sepúlveda, N. Editorial: On the cusp of the silent wave of the long COVID pandemic: why, what and how should we tackle this emerging syndrome in the clinic and population? Front. Public Health. 2024 Oct 23;12:1483693. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Straus, S.E.; Hickie, I.; Sharpe, M.C.; Dobbins, J.G.; Komaroff, A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994 Dec 15;121(12):953-9. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, L.; Bested, A.C.; Bonilla, H.F.; Chheda, B.V.; Chu, L.; Curtin, J.M.; Dempsey, T.T.; Dimmock, M.E.; Dowell, T.G.; Felsenstein, D. et al. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Essentials of Diagnosis and Management. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021 Nov;96(11):2861-2878. [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, A.V.; Jayadevan, R.; Sashidharan, S. Long COVID: An overview. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2021 May-Jun;15(3):869-875. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007. Erratum in: Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022 May;16(5):102504. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102504. Erratum in: Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022 Dec;16(12):102660. [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Khodayari, Y.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Zarei, H.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Akbari, H.; Mohammadi, M. Global prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome among long COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2022 October 23;16(1):21. [CrossRef]

- Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y. et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 Aug;38:101019. [CrossRef]

- Haffke, M.; Freitag, H.; Rudolf, G.; Seifert, M.; Doehner, W.; Scherbakov, N.; Hanitsch, L.; Wittke, K.; Bauer, S.; Konietschke, F. et al. Endothelial dysfunction and altered endothelial biomarkers in patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). J. Transl. Med. 2022 Mar 22;20(1):138. [CrossRef]

- Kedor, C.; Freitag, H.; Meyer-Arndt, L.; Wittke, K.; Hanitsch, L.G.; Zoller, T.; Steinbeis, F.; Haffke, M.; Rudolf, G.; Heidecker, B. et al. A prospective observational study of post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome following the first pandemic wave in Germany and biomarkers associated with symptom severity. Nat. Commun. 2022 Aug 30;13(1):5104. [CrossRef]

- Tokumasu, K.; Honda, H.; Sunada, N.; Sakurada, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakano, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Otsuka, Y. et al. Clinical Characteristics of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Diagnosed in Patients with Long COVID. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Jun 25;58(7):850. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.; Williams, M.A. Confronting Our Next National Health Disaster - Long-Haul Covid. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021 Aug 12;385(7):577-579. [CrossRef]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Bateman, L. Will COVID-19 Lead to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Front. Med. (Lausanne). 2021 Jan 18;7:606824. [CrossRef]

- Morita, S.; Tokumasu, K.; Otsuka, Y.; Honda, H.; Nakano, Y.; Sunada, N.; Sakurada, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Soejima, Y.; Ueda, K. et al. Phase-dependent trends in the prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) related to long COVID: A criteria-based retrospective study in Japan. PLoS One. 2024 Dec 9;19(12):e0315385. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, R.; Rahman, M.M.; Rassel, M.A.; Monayem, F.B.; Sayeed, S.K.J.B.; Islam, M.S.; Islam, M.M. Post-COVID-19 syndrome among symptomatic COVID-19 patients: A prospective cohort study in a tertiary care center of Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2021 Apr 8;16(4):e0249644. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ramirez, D.C.; Normand, K.; Zhaoyun, Y.; Torres-Castro, R. Long-Term Impact of COVID-19: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines. 2021 Jul 27;9(8):900. [CrossRef]

- Hejbøl, E.K.; Harbo, T.; Agergaard, J.; Madsen, L.B.; Pedersen, T.H.; Østergaard, L.J.; Andersen, H.; Schrøder, H.D.; Tankisi, H. Myopathy as a cause of fatigue in long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms: Evidence of skeletal muscle histopathology. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022 Sep;29(9):2832-2841. [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Patel, K.; Pinto, C.; Jaiswal, R.; Tirupathi, R.; Pillai, S.; Patel, U. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)-A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2022 Jan;94(1):253-262. [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.M.E.; Maffitt, N.J.; Del Vecchio, A.; McKeating, K.M.; Baker, M.R.; Baker, S.N.; Soteropoulos, D.S. Neural dysregulation in post-COVID fatigue. Brain Commun. 2023 Apr 12;5(3):fcad122. [CrossRef]

- Kouyoumdjian, J.A.; Yamamoto, L.A.R.; Graca, C.R. Jitter and muscle fiber conduction velocity in long COVID fatigue. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2025 Jan;83(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Tsampasian, V.; Elghazaly, H.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Debski, M.; Naing, T.K.P.; Garg, P.; Clark, A.; Ntatsaki, E.; Vassiliou, V.S. Risk Factors Associated With Post-COVID-19 Condition: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J.A.M.A. Intern. Med. 2023 Jun 1;183(6):566-580. [CrossRef]

- Buttery, S.; Philip, K.E.J.; Williams, P.; Fallas, A.; West, B.; Cumella, A.; Cheung, C.; Walker, S.; Quint, J.K.; Polkey, M.I. et al. Patient symptoms and experience following COVID-19: results from a UK-wide survey. B.M.J. Open Respir. Res. 2021 Nov;8(1):e001075. [CrossRef]

- Salamanna, F.; Veronesi, F.; Martini, L.; Landini, M.P.; Fini, M. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: The Persistent Symptoms at the Post-viral Stage of the Disease. A Systematic Review of the Current Data. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 2021 May 4;8:653516. [CrossRef]

- Alkodaymi, M.S.; Omrani, O.A.; Ashraf, N.; Shaar, B.A.; Almamlouk, R.; Riaz, M.; Obeidat, M.; Obeidat, Y,; Gerberi, D.; Taha, R.M. et al. Prevalence of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022 May;28(5):657-666. [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.M.W.; Lee, Y.; Gill, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Cao, B. et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022 Mar;101:93-135. [CrossRef]

- Angarita-Fonseca, A.; Torres-Castro, R.; Benavides-Cordoba, V.; Chero, S.; Morales-Satán, M.; Hernández-López, B.; Salazar-Pérez, R.; Larrateguy, S.; Sanchez-Ramirez, D.C. Exploring long COVID condition in Latin America: Its impact on patients' activities and associated healthcare use. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 2023 April 20;10:1168628. [CrossRef]

- Kisiel, M.A.; Lee, S.; Malmquist, S.; Rykatkin, O.; Holgert, S.; Janols, H.; Janson, C.; Zhou, X. Clustering Analysis Identified Three Long COVID Phenotypes and Their Association with General Health Status and Working Ability. J. Clin. Med. 2023 May 23;12(11):3617. [CrossRef]

- Malheiro, D.T.; Bernardez-Pereira, S.; Parreira, K.C.J.; Pagliuso, J.G.D.; de Paula Gomes, E.; de Mesquita Escobosa, D.; de Araújo, C.I.; Pimenta, B.S.; Lin, V.; de Almeida, S.M. et al. Prevalence, predictors, and patient-reported outcomes of long COVID in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients from the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Front. Public Health. 2024 Jan 22;11:1302669. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Mohan, A.; Upadhyay, V. Long COVID syndrome: An unfolding enigma. Indian J. Med. Res. 2024 Jun;159(6):585-600. [CrossRef]

- Abrams, R.M.C.; Zhou, L.; Shin, S.C. Persistent post-COVID-19 neuromuscular symptoms. Muscle Nerve. 2023 Oct;68(4):350-355. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.S.; Aghoram, R.; Wadwekar, V.; Nanda, N. Skeletal muscle injury in COVID infection: Frequency and patterns. Muscle Nerve. 2023 Nov;68(6):873-878. [CrossRef]

- Seeck, M.; Tankisi, H. Clinical neurophysiological tests as objective measures for acute and long-term COVID-19. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 2023;8:1-2. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).