Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion

2.2.2. Exclusion

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Organisation Process

2.6. Risk of Bias

3. Results

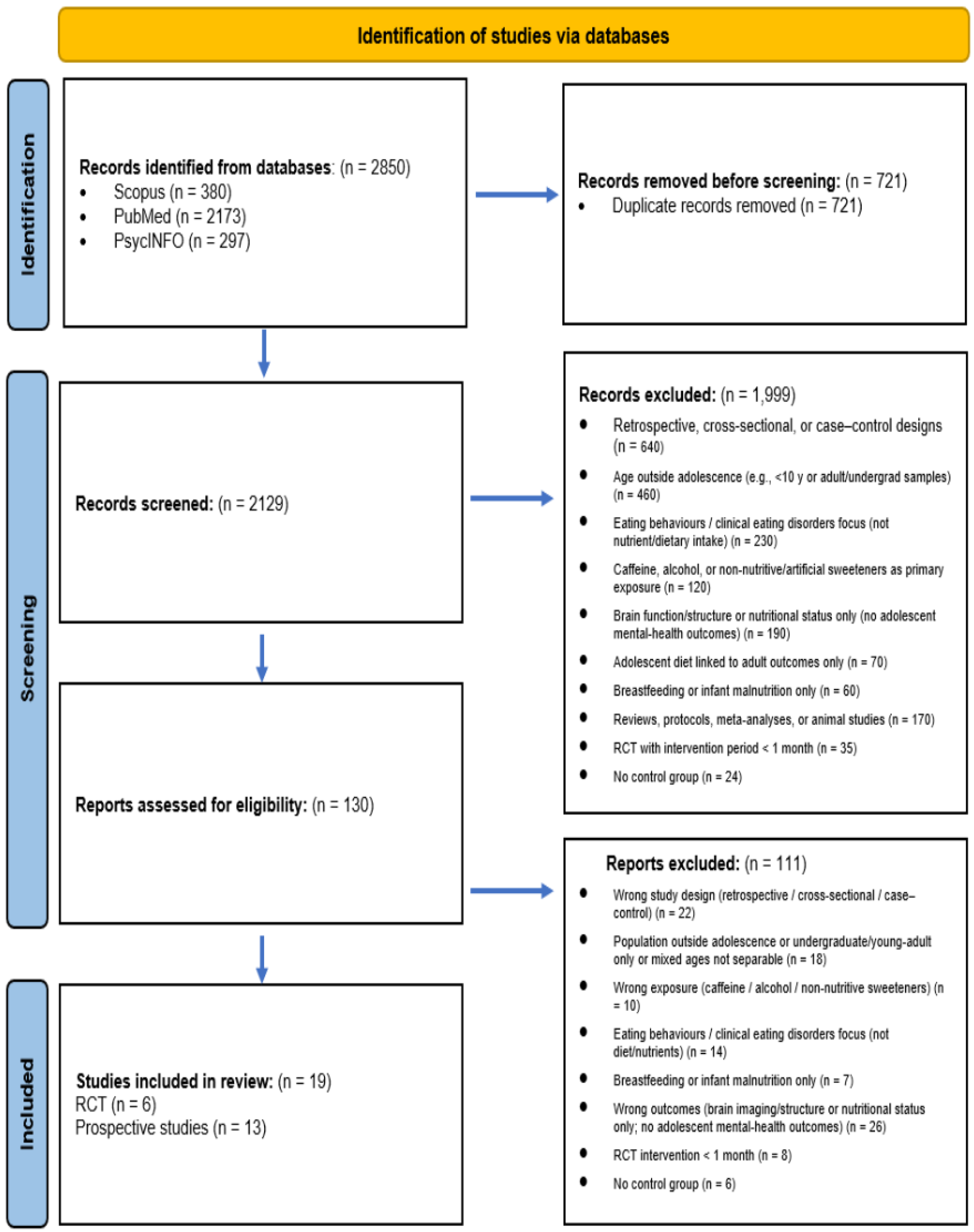

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs)

3.2.1. Vitamin D Supplementation

3.2.2. Fatty Acids

3.2.3. Polyphenols/Wild Blueberry

3.2.4. Summary of Randomized Controlled Trials

3.3. Prospective Studies

3.3.1. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet (MD)

3.3.2. Macronutrient Intake

3.3.3. Micronutrient Intake

3.3.4. Soft Drink Consumption

3.3.5. Quality of Dietary Patterns

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Randomised Controlled Trials

4.2. Prospective Studies

4.2.1. The Influence of Sex and Socioeconomic Status (SES)

4.2.2. Sex-Specific Associations

4.2.3. Socioeconomic Status

4.3. General Methodological Considerations

4.4. Limitations and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dimov, S.; Mundy, L.K.; Bayer, J.K.; Jacka, F.N.; Canterford, L.; Patton, G.C. Diet quality and mental health problems in late childhood. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 24, 62–70. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, L.; A Savel, K.; Madigan, S.; Colasanto, M.; Korczak, D.J. Dietary patterns and internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2021, 56, 617–641. [CrossRef]

- Wickersham, A.; Sugg, H.V.; Epstein, S.; Stewart, R.; Ford, T.; Downs, J. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: The Association Between Child and Adolescent Depression and Later Educational Attainment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 105–118. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Amminger, G.P.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Lee, S.; Üstün, T.B. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 359–364. [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.E., et al., Adult functional outcomes of common childhood psychiatric problems: a prospective, longitudinal study. JAMA psychiatry, 2015. 72(9): p. 892-899.

- Kazdin, A.E.; Rabbitt, S.M. Novel Models for Delivering Mental Health Services and Reducing the Burdens of Mental Illness. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 1, 170–191. [CrossRef]

- Benton, D. The influence of dietary status on the cognitive performance of children. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 457–470. [CrossRef]

- Craigie, A.M.; Lake, A.A.; Kelly, S.A.; Adamson, A.J.; Mathers, J.C. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 70, 266–284. [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship Between Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e31–e42. [CrossRef]

- Lassale, C.; Batty, G.D.; Baghdadli, A.; Jacka, F.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Akbaraly, T. Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 965–986. [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Travica, N.; Dissanayaka, T.; Ashtree, D.N.; Gauci, S.; Lotfaliany, M.; O’neil, A.; Jacka, F.N.; Marx, W. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2568. [CrossRef]

- Pruneti, C.; Guidotti, S. Need for Multidimensional and Multidisciplinary Management of Depressed Preadolescents and Adolescents: A Review of Randomized Controlled Trials on Oral Supplementations (Omega-3, Fish Oil, Vitamin D3). Nutrients 2023, 15, 2306. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.E.M., et al., Dietary Pattern and Depressive Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Nutr Rev, 2025. 83(9): p. 1725-1742.

- Fried, E.I. The 52 symptoms of major depression: Lack of content overlap among seven common depression scales. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 191–197. [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Flake, J.K.; Robinaugh, D.J. Revisiting the theoretical and methodological foundations of depression measurement. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 358–368. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J., et al., The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Revista panamericana de salud pública, 2022. 46.

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [CrossRef]

- Grung, B.; Sandvik, A.M.; Hjelle, K.; Dahl, L.; Frøyland, L.; Nygård, I.; Hansen, A.L. Linking vitamin D status, executive functioning and self-perceived mental health in adolescents through multivariate analysis: A randomized double-blind placebo control trial. Scand. J. Psychol. 2017, 58, 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Isaac, H.A.; Hemamalini, A.J.; Seshadri, K.; Ravichandran, L. Impact of vitamin D fortified food on quality of life and emotional difficulties among adolescents – A randomized controlled trial. Indian J. Child Heal. 2019, 6, 56–60. [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, P.T.; Suryanarayana, R.; Ty, S.; Reddy, S.; Ag, N. Does Vitamin D3 Supplementation Improve Depression Scores among Rural Adolescents? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 2024. 16(12): p. 1828.

- van der Wurff, I.; von Schacky, C.; Bergeland, T.; Leontjevas, R.; Zeegers, M.; Kirschner, P.; de Groot, R. Effect of one year krill oil supplementation on depressive symptoms and self-esteem of Dutch adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2020, 163, 102208. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.O.; Jackson, P.A.; Elliott, J.M.; Scholey, A.B.; Robertson, B.C.; Greer, J.; Tiplady, B.; Buchanan, T.; Haskell, C.F. Cognitive and mood effects of 8 weeks' supplementation with 400 mg or 1000 mg of the omega-3 essential fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in healthy children aged 10–12 years. Nutr. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 48–56. [CrossRef]

- Fisk, J.; Khalid, S.; Reynolds, S.A.; Williams, C.M. Effect of 4 weeks daily wild blueberry supplementation on symptoms of depression in adolescents. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 181–188. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, E.; Canals, J.; Voltas, N.; Valenzano, A.; Arija, V. Emotional Symptoms and Dietary Patterns in Early Adolescence: A School-Based Follow-up Study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 405–414.e1. [CrossRef]

- Hayek, J.; de Vries, H.; Tueni, M.; Lahoud, N.; Winkens, B.; Schneider, F. Increased Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Higher Efficacy Beliefs Are Associated with Better Academic Achievement: A Longitudinal Study of High School Adolescents in Lebanon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 6928. [CrossRef]

- Winpenny, E.M.; van Harmelen, A.-L.; White, M.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Goodyer, I.M. Diet quality and depressive symptoms in adolescence: no cross-sectional or prospective associations following adjustment for covariates. Public Health Nutr 2018, 21, 2376–2384. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Jakowski, S.; Kellmann, M.; Cody, R.; Gygax, B.; Ludyga, S.; Müller, C.; Ramseyer, S.; Beckmann, J. Macronutrient intake as a prospective predictor of depressive symptom severity: An exploratory study with adolescent elite athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 67. [CrossRef]

- Swann, O.G.; Breslin, M.; Kilpatrick, M.; O’sullivan, T.A.; Mori, T.A.; Beilin, L.J.; Lin, A.; Oddy, W.H. Dietary fibre intake and its associations with depressive symptoms in a prospective adolescent cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 125, 1166–1176. [CrossRef]

- Black, L.J.; Allen, K.L.; Jacoby, P.; Trapp, G.S.; Gallagher, C.M.; Byrne, S.M.; Oddy, W.H. Low dietary intake of magnesium is associated with increased externalising behaviours in adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2014, 18, 1824–1830. [CrossRef]

- Tolppanen, A.M., et al., The association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D 3 and D 2 with depressive symptoms in childhood – a prospective cohort study. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 2012. 53(7): p. 757-766.

- Mrug, S.; Jones, L.C.; Elliott, M.N.; Tortolero, S.R.; Peskin, M.F.; Schuster, M.A. Soft Drink Consumption and Mental Health in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Examination. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2021, 68, 155–160. [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F.N.; Rothon, C.; Taylor, S.; Berk, M.; Stansfeld, S.A. Diet quality and mental health problems in adolescents from East London: a prospective study. Chest 2012, 48, 1297–1306. [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F.N.; Kremer, P.J.; Berk, M.; De Silva-Sanigorski, A.M.; Moodie, M.; Leslie, E.R.; Pasco, J.A.; Swinburn, B.A. A Prospective Study of Diet Quality and Mental Health in Adolescents. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e24805. [CrossRef]

- Oddy, W.H.; Allen, K.L.; Trapp, G.S.; Ambrosini, G.L.; Black, L.J.; Huang, R.-C.; Rzehak, P.; Runions, K.C.; Pan, F.; Beilin, L.J.; et al. Dietary patterns, body mass index and inflammation: Pathways to depression and mental health problems in adolescents. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2018, 69, 428–439. [CrossRef]

- Trapp, G.S.A.; Allen, K.L.; Black, L.J.; Ambrosini, G.L.; Jacoby, P.; Byrne, S.; Martin, K.E.; Oddy, W.H. A prospective investigation of dietary patterns and internalizing and externalizing mental health problems in adolescents. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 888–896. [CrossRef]

- Dabravolskaj, J.; Patte, K.A.; Yamamoto, S.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Veugelers, P.J.; Maximova, K. Association Between Diet and Mental Health Outcomes in a Sample of 13,887 Adolescents in Canada. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2024, 21, E82. [CrossRef]

- Howe, L.D., et al., Loss to follow-up in cohort studies: bias in estimates of socioeconomic inequalities. Epidemiology, 2013. 24(1): p. 1-9.

- Varni, J.W., M. Seid, and P.S. Kurtin, PedsQL™ 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical care, 2001. 39(8): p. 800-812.

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [CrossRef]

- Angold, A., et al., Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents: factor composition and structure across development. International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 1996. 5(4): p. 251-262.

- Beck, J.S., Beck youth inventories of emotional & social impairment: Depression inventory for youth, anxiety inventory for youth, anger inventory for youth, disruptive behavior inventory for youth, self-concept inventory for youth: Manual. 2001: Psychological Corporation New York, NY, USA.

- Radloff, L.S., A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychol Measurements, 1977. 1: p. 385-401.

- Beck, A.; Dryburgh, N.; Bennett, A.; Shaver, N.; Esmaeilisaraji, L.; Skidmore, B.; Patten, S.; Bragg, H.; Colman, I.; Goldfield, G.S.; et al. Screening for depression in children and adolescents in primary care or non-mental health settings: a systematic review update. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Mullarkey, M.C.; Marchetti, I.; Bluth, K.; Carlson, C.L.; Shumake, J.; Beevers, C.G. Symptom centrality and infrequency of endorsement identify adolescent depression symptoms more strongly associated with life satisfaction. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 289, 90–97. [CrossRef]

- Mullarkey, M.C.; Marchetti, I.; Beevers, C.G. Using Network Analysis to Identify Central Symptoms of Adolescent Depression. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 656–668. [CrossRef]

- Stevanovic, D.; Jafari, P.; Knez, R.; Franic, T.; Atilola, O.; Davidovic, N.; Bagheri, Z.; Lakic, A. Can we really use available scales for child and adolescent psychopathology across cultures? A systematic review of cross-cultural measurement invariance data. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 125–152. [CrossRef]

- Duinhof, E.L.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; van Dorsselaer, S.; Monshouwer, K.; Vollebergh, W.A.M. Ten-year trends in adolescents’ self-reported emotional and behavioral problems in the Netherlands. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 24, 1119–1128. [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Papanikolaou, F.; Epskamp, S. Mental Health and Social Contact During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 10, 340–354. [CrossRef]

- Young, H.A.; Cousins, A.L.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Benton, D.; Gershon, R.C.; Ghirardelli, A.; Latulippe, M.E.; Scholey, A.; Wagstaff, L. Alignment of Consumers’ Expected Brain Benefits from Food and Supplements with Measurable Cognitive Performance Tests. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1950. [CrossRef]

- Veal, C.; Tomlinson, A.; Cipriani, A.; Bulteau, S.; Henry, C.; Müh, C.; Touboul, S.; De Waal, N.; Levy-Soussan, H.; A Furukawa, T.; et al. Heterogeneity of outcome measures in depression trials and the relevance of the content of outcome measures to patients: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11, 285–294. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.J.; Moore, J.A.; Griffiths, A.R.; Cousins, A.L.; Young, H.A. Unveiling Dietary Complexity: A Scoping Review and Reporting Guidance for Network Analysis in Dietary Pattern Research. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3261. [CrossRef]

- A Young, H.; Geurts, L.; Scarmeas, N.; Benton, D.; Brennan, L.; Farrimond, J.; Kiliaan, A.J.; Pooler, A.; Trovò, L.; Sijben, J.; et al. Multi-nutrient interventions and cognitive ageing: are we barking up the right tree?. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2022, 36, 471–483. [CrossRef]

- Bánáti, D.; Hellman-Regen, J.; Mack, I.; Young, H.A.; Benton, D.; Eggersdorfer, M.; Rohn, S.; Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Krężel, W.; Rühl, R. Defining a vitamin A5/X specific deficiency – vitamin A5/X as a critical dietary factor for mental health. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2024, 94, 443–475. [CrossRef]

- Laube, C.; Bos, W.v.D.; Fandakova, Y. The relationship between pubertal hormones and brain plasticity: Implications for cognitive training in adolescence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2020, 42, 100753. [CrossRef]

- Opie, R.S.; O’neil, A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Jacka, F.N. The impact of whole-of-diet interventions on depression and anxiety: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutr 2015, 18, 2074–2093. [CrossRef]

- Benton, D.; Young, H.A. Early exposure to sugar sweetened beverages or fruit juice differentially influences adult adiposity. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 78, 521–526. [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F. N.; O'Neil, A.; Opie, R.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Cotton, S.; Mohebbi, M.; Castle, D.; Dash, S.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Chatterton, M. L. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’trial). BMC Med. 2017, 15, 23.

- Young, H.A.; Benton, D. Heart-rate variability: a biomarker to study the influence of nutrition on physiological and psychological health?. Behav. Pharmacol. 2018, 29, 140–151. [CrossRef]

- A Young, H.; Freegard, G.; Benton, D. Mediterranean diet, interoception and mental health: Is it time to look beyond the ‘Gut-brain axis’?. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 257, 113964. [CrossRef]

- Gaylor, C.M.; Brennan, A.; Blagrove, M.; Tulip, C.; Bloxham, A.; Williams, S.; Tucker, R.; Benton, D.; Young, H.A. Low and high glycemic index drinks differentially affect sleep polysomnography and memory consolidation: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Res. 2025, 134, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Sparling, T.M.; Deeney, M.; Cheng, B.; Han, X.; Lier, C.; Lin, Z.; Offner, C.; Santoso, M.V.; Pfeiffer, E.; Emerson, J.A.; et al. Systematic evidence and gap map of research linking food security and nutrition to mental health. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Romijn, A.R.; Latulippe, M.E.; Snetselaar, L.; Willatts, P.; Melanson, L.; Gershon, R.; Tangney, C.; Young, H.A. Perspective: Advancing Dietary Guidance for Cognitive Health—Focus On Solutions to Harmonize Test Selection, Implementation, and Evaluation. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2023, 14, 366–378. [CrossRef]

| Author (year) | Country | Sub-Category | Dose & Duration | Sample Size (N) | Sample Characteristics | Measures | Sex-Specific Analysis? | SES/Deprivation Adjusted? | Key Findings | Biomarker Verified? |

| Fisk et al. (2020) | UK | Polyphenols | ~253 mg anthocyanins/day for 4 weeks | 64 | 12–17 y, Mixed sex | MFQ, RCADS, PANAS | No | NR | ↓ Depressive symptoms NS Anxiety & Affect |

No |

| Grung et al. (2017) | Norway | Vitamin D | 1,520 IU/day for ~3 months | 50 | 13–14 y, Mixed sex | YSR-CBCL, ToH, ToL | No | NR | NS Internalising/Externalising ↑ Executive function (ToH) |

Yes (25(OH)D) |

| Isaac et al. (2019) | India | Vitamin D | 1,000 IU/day for 12 weeks | 71 | 11–16 y, Mixed sex, Vit D deficient | WHOQOL-BREF, DASS-21 | No | NR | NS Quality of Life NS Anxiety/Stress |

Yes (25(OH)D) |

| Kennedy et al. (2009) | UK | Omega-3 | 400 or 1,000 mg/day (DHA) for 8 weeks | 90 | 10–12 y, Healthy, Mixed sex | CDR battery, VAS mood | No | NR | NS Mood & Cognition | No |

| Satyanarayana et al. (2024) | India | Vitamin D | ~2,250 IU/day for 9 weeks | 451 | 14–19 y, Rural, Mixed sex | BDI-II | No | NR | ↓ Depressive symptoms | Yes (25(OH)D) |

| van der Wurff et al. (2020) | Netherlands | Omega-3 | 400→800 mg/day (EPA+DHA) for 12 months | 256 | 14–15 y, Low O3I, Mixed sex | CES-D, RSE | No | Yes (parental education). Did not affect results. | NS Depressive symptoms NS Self-esteem |

Yes (O3I) |

| Aparicio et al. (2017) | Spain | Mediterranean Diet | MD adherence & patterns; 3-year follow-up | 165 | ~13.5 y, School cohort | SCARED, CDI, YI-4 | Yes. Emotional symptoms linked to poorer diet in females only. | Yes (Hollingshead index). Association remained significant after adjustment; SES was also a predictor. | ↑ Emotional symptoms → ↓ MD adherence (Females only, reverse causality tested) |

| Author (year) | Country | Sub-Category | Dietary Exposure & Follow-up | Sample Size (N) | Sample Characteristics | Measures | Sex-Specific Analysis? | SES/Deprivation Adjusted? | Key Findings |

| Black et al. (2015) | Australia | Micronutrients | Zinc & Magnesium intake; 3-year follow-up | 684 | 14 & 17 y, General pop. | YSR | No (Interactions tested, NS). | Yes (Family income). Association was significant only after adjustment. | ↑ Magnesium → ↓ Externalising problems |

| Dabravolskaj et al. (2024) | Canada | Overall Diet Quality | Frequency of fruit/veg, SSB, junk food, breakfast intake; 1-year follow-up | 13,887 | Adolescents (grades 9–12); mean age 15 y; 52% female; general pop. | “Diet: COMPASS survey items | Yes. SSB associations stronger in males. | Yes (Adjusted for weekly spending money, plus lifestyle & psychosocial factors). | ↑ SSB intake → ↑ Depressive (β=0.04) & Anxiety symptoms (β=0.02), ↓ Well-being (β=-0.03). ↑ F&V intake → ↑ Well-being (β=0.06), NS Depressive/Anxiety symptoms (after full adjustment) |

| Gerber et al. (2023) | Switzerland | Macronutrients | Protein intake from food recall; 10-month follow-up | 79 | ~16.4 y, Elite athletes | PHQ-9 | No. | No. (Measured but excluded from the final model as it was not a significant predictor). | ↑ Protein → ↓ Depressive symptoms |

| Hayek et al. (2021) | Lebanon | Mediterranean Diet | MD adherence (KIDMED); 1-year follow-up | 563 | 15–18 y, School cohort | Academic Grade | No. | Yes (Parental education). Association remained significant after adjustment. | ↑ MD Adherence → ↑ Academic Achievement (Not MH symptoms) |

| Jacka (2013) | UK | Overall Diet Quality | Healthy vs. unhealthy diet; 2-year follow-up | 2,383 | 11–14 y, Socially deprived | SDQ, SMFQ | No (Interactions tested, NS). | Yes (e.g., free school meals). Overall adjustment attenuated the prospective link. | ↑ Unhealthy diet → ↑ MH problems (effect attenuated after full adjustment) |

| Jacka et al. (2011) | Australia | Overall Diet Quality | Healthful vs. unhealthful patterns; 2-year follow-up | 2,915 | 11–18 y, General pop. | PedsQL | No (Interactions tested, NS). | Yes (SEIFA area index). Associations remained significant after adjustment. | ↑ Healthy diet → ↑ Emotional functioning ↑ Unhealthy diet → ↓ Emotional functioning |

| Mrug et al. (2021) | USA | Soft Drinks | Soft drink frequency; 5-year follow-up (3 waves) | 5,147 | 11, 13 & 16 y, Diverse pop. | Aggression/Depression Scales | No. | Yes (Education & income). Associations remained significant after adjustment. | ↑ Soft Drinks → ↑ Aggression (bidirectional link found) |

| Oddy et al. (2018) | Australia | Overall Diet Quality | Western’ vs. ‘Healthy’ patterns; 3-year follow-up | 843 | 14 & 17 y, General pop. | BDI-Y, YSR | No (Interactions tested, NS). | Yes (Income & education). Associations remained significant after adjustment. | ↑ Western diet → ↑ Depressive symptoms & MH problems (mediated by inflammation) |

| Swann et al. (2021) | Australia | Macronutrients | Dietary fibre intake; 3-year follow-up | 1260 | 14 & 17 y, General pop. | BDI-Y | No (Interactions tested, NS). | Yes (Education & income). Association was significant after SES adjustment but was attenuated by overall dietary pattern. | ↑ Fibre → ↓ Depressive symptoms (attenuated by overall diet quality) |

| Tolppanen et al. (2012) | UK | Micronutrients | Serum Vitamin D₃ (biomarker); ~4-year follow-up | 2,752 | ~10 to ~14 y, General pop. | MFQ | No (Interactions tested, NS). | Yes (Occupation & education). Associations remained significant after adjustment. | ↑ Vitamin D₃ → ↓ Depressive symptoms |

| Trapp et al. (2016) | Australia | Overall Diet Quality | Healthy’ vs. ‘Western’ patterns; 3-year follow-up | 746 | 14 & 17 y, General pop. | YSR | Yes. Link between ‘Western’ diet & externalising found in females only. | Yes (Income & education). Association was significant only after full adjustment. | ↑ Western diet → ↑ Externalising problems (Females only) |

| Winpenny et al. (2018) | UK | Mediterranean Diet | MD score from diet diary; 3-year follow-up | 603 | 14.5 & 17.5 y, General pop. | MFQ | Yes. Stratified analysis; no significant associations found in either sex. | Yes (Postcode index). Associations became non-significant after full adjustment. | NS MD Adherence → Depressive symptoms (after full adjustment) |

| Priority area | Significance | Design implications | Measurement & biomarkers | Equity & implementation | Example research question |

| Symptom-based outcomes (beyond diagnoses) | Captures heterogeneity; avoids masking effects in composite totals | Pre-specify primary symptom domains; analyse subscales/items alongside total using appropriate statistical methods | Check that measures work the same across groups (measurement invariance); use multiple informants (young person, parent/carer, teacher, clinician) | Use culturally adapted, validated tools developed with young people | Does improving diet quality reduce anhedonia or irritability specifically in adolescents? |

| Harmonised core outcome sets | Enables synthesis and comparison across studies | Build a consensus minimal set via Delphi with youth, carers, clinicians, educators to measure priority outcomes | Map existing tools to prioritised outcomes; Determine which priority outcomes lack adequate, validated measurement tools.; Develop and validate measures specifically designed to fill those identified gaps. | Co-produce outcomes that matter in schools, clinics and everyday life. | What minimal battery best balances burden and validity across settings? |

| Better exposure assessment | Reduces misclassification of diet | Combine repeated 24-hour recalls/diaries with food-frequency tools; include calibration subsamples | Add objective markers: vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D), omega-3 index, carotenoids; digital capture (meal photos, receipts) | Choose methods feasible in low-resource schools/ communities | How do repeated objective diet measures change effect estimates versus food-frequency tools alone? |

| Biomarker-informed trials | Strengthens causal inference | Target adolescents with low baseline status; stratify randomisation; ensure adequate duration and contrast | Verify exposure change (e.g., vitamin D and omega-3 indices); include inflammation, glycaemic control, neurotrophic factors, microbiome/metabolites | Low-burden sampling (dried blood spots; postal stool kits) | Do adolescents with low vitamin D show greater mood benefit from diet improvement than replete peers? |

| Dietary network methods (MRS-DN) | Tests synergy rather than single nutrients | Pre-register network models; compare with traditional indices | Report estimation, stability, and sensitivity per the checklist | Build analyst capacity; share code and data | Which food–nutrient constellations most robustly predict symptom improvement? |

| Longitudinal causal modelling | Clarifies direction of effects | Use within-person change or cross-lagged models; emulate target trials when randomisation is infeasibleᶜ | Align timing of diet and outcome waves | Plan for retention; minimise burden | Do changes in sugar-sweetened drink intake precede changes in externalising behaviours within individuals? |

| Mechanistic integration | Links biology to symptoms | Embed mechanistic sub-studies in trials and cohorts | Panels for inflammation, glycaemic control, lipidomics, metabolomics, microbiome, neurotrophic markers | Use affordable, standardised panels; control for batch effects | Are mood benefits mediated by reductions in systemic inflammation? |

| Early-life to adolescence | Tests timing and sensitive periods | Link infancy diet to adolescent outcomes with repeated measures | Include stable markers (e.g., ferritin), growth, and diet trajectories | Maintain diverse cohorts; consider attrition bias | Do infancy diet trajectories interact with adolescent diet to influence mood? |

| Multi-level context | Accounts for confounding and leverage points | Measure family, school, neighbourhood food environments | Include mealtime practices, food insecurity, marketing exposure | Oversample under-resourced and high-risk groups | Does family meal frequency change the effect of diet quality on anxiety? |

| Sex & Gender Analysis | Addresses findings that diet-mental health links may be stronger or exclusive to females; clarifies vulnerability. | Power studies adequately to test for sex/gender interactions; pre-specify stratified analyses rather than adding them post-hoc. | Collect data on sex assigned at birth and gender identity; consider hormonal status/pubertal stage as a potential moderator. | Ensure interventions and recommendations are relevant and communicated effectively to adolescents of all genders. | Is the prospective link between a ‘Western’ diet and externalising behaviours stronger in adolescent girls than in boys? |

| Socioeconomic & Environmental Context | Disentangles the independent effect of diet from the powerful confounding effects of deprivation, stress, and food insecurity. | Use robust, multi-domain SES measures (parental income, education, area-level deprivation); measure the food environment (e.g., food deserts). | Validated SES indices (e.g., SEIFA); household food insecurity scales; geospatial data on local food outlets. | Oversample low-SES and high-risk groups; co-design interventions that are affordable, accessible, and culturally appropriate. | Does the effect of a healthy diet on depressive symptoms persist after fully accounting for family income and food insecurity? |

| Implementation and scale-up | Ensures real-world impact | Hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs | Track fidelity, reach, cost, acceptability, and equity metrics | Co-design with schools and commissioners | What is the cost per meaningful gain in wellbeing for a school diet programme? |

| Open science and standardisation | Improves trust and synthesis | Register protocols; share data and code; use reporting checklists | Common data dictionaries; transparent preprocessing | Capacity building and training | Does pre-registration reduce outcome-reporting bias in diet–mental health trials? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).