Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

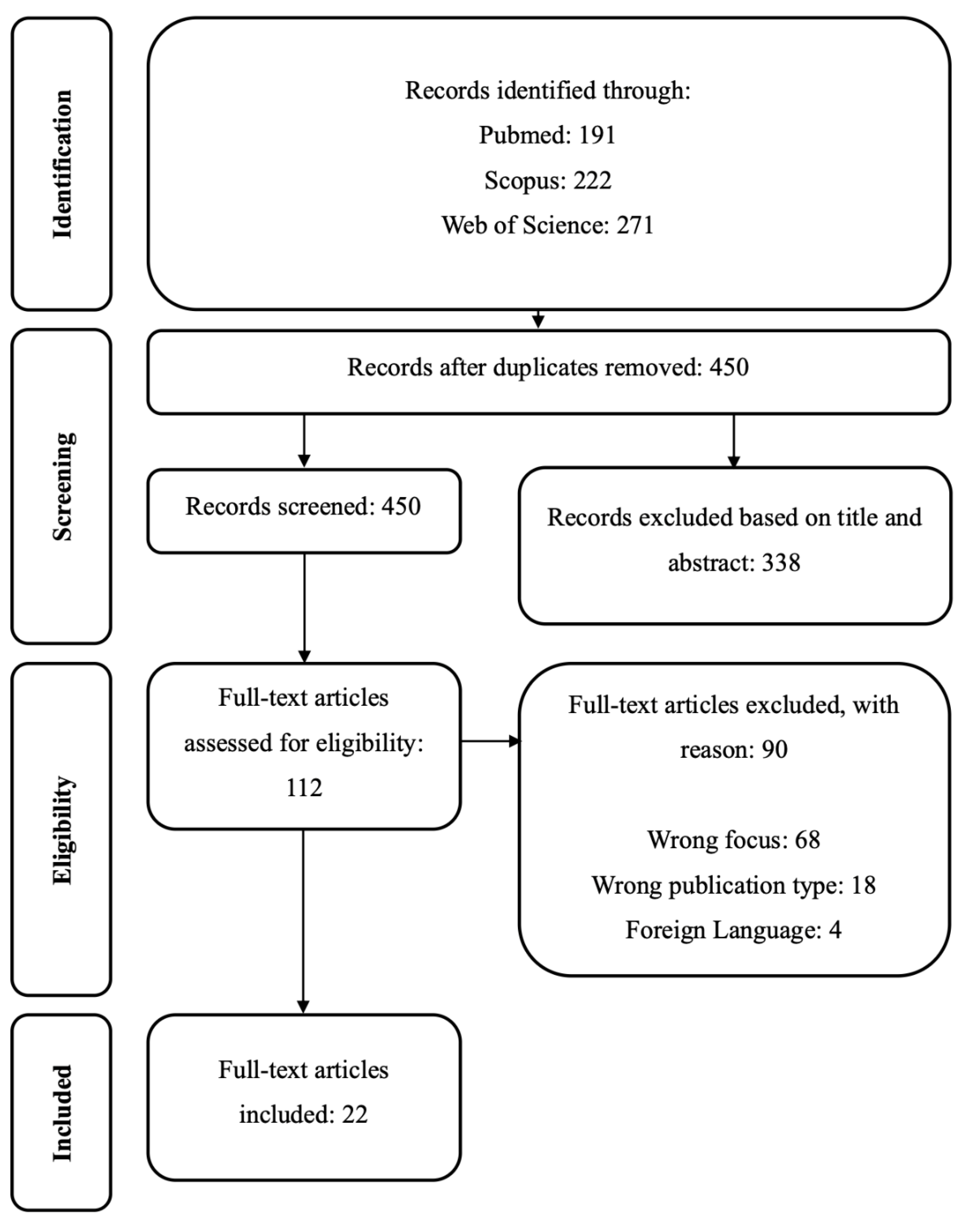

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Descriptive Mapping of Selected Papers

2.6. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Discrimination Manifestations

3.1.1. Structural and Overt Discrimination

3.1.2. Interpersonal and Subtle Discrimination

3.1.3. Implicit Bias and Stereotyping Mechanisms

3.2. Theme 2: Health and Professional Outcomes

3.2.1. Mental Health Consequences

3.2.2. Physical Health Implications

3.2.3. Professional and Social Functioning

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Other statements and declaration

Citation Diversity Statement

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Obodo, C. A. (2021). Gender-Related Discrimination. In W. Leal Filho, A. Marisa Azul, L. Brandli, A. Lange Salvia, P. Gökçin Özuyar, & T. Wall (A c. Di), Reduced Inequalities (pp. 289–299). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- De Vries, A. L. C. , Kreukels, B. P. C., Steensma, T. D., & McGuire, J. K. (2014). Gender Identity Development: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. In B. P. C. Kreukels, T. D. Steensma, & A. L. C. De Vries (A c. Di), Gender Dysphoria and Disorders of Sex Development (pp. 53–80). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Eckes, T. , & Trautner, H. M. (A c. Di). (2012). The Developmental social psychology of gender. [CrossRef]

- Egan, S. K. , & Perry, D. G. Gender identity: A multidimensional analysis with implications for psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology 2001, 37, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibbi, R. , Midtbøen, A. H., & Simon, P. (2021). Concepts of Discrimination. In R. Fibbi, A. H. Midtbøen, & P. Simon, Migration and Discrimination (pp. 13–20). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S. T. J. , Myer, A., & Berney, E. C. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination at the intersection of race and gender: An intersectional theory primer. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2024, 18, e12939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junça-Silva, A. , & Ferreira, N. (2025). Workplace micro-aggressions and affective consequences: The moderating role of emotional contagion. Current Psychology. [CrossRef]

- McAllister, A. , Fritzell, S., Almroth, M., Harber-Aschan, L., Larsson, S., & Burström, B. How do macro-level structural determinants affect inequalities in mental health? – A systematic review of the literature. International Journal for Equity in Health 2018, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, S. , & Embrick, D. G. Racial microaggressions: Bridging psychology and sociology and future research considerations. Sociology Compass 2020, 14, e12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. , Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Dovidio, J. How Does Stigma “Get Under the Skin”?: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. Psychological Science 2009, 20, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzina, R. , Gopikumar, V., Jenkins, J., Saraceno, B., & Sashidharan, S. P. Social Vulnerability and Mental Health Inequalities in the “Syndemic”: Call for Action. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13, 894370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurz, M. , Radua, J., Tholen, M. G., Maliske, L., Margulies, D. S., Mars, R. B., Sallet, J., & Kanske, P. Toward a hierarchical model of social cognition: A neuroimaging meta-analysis and integrative review of empathy and theory of mind. Psychological Bulletin 2021, 147, 293–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawronski, B. , Ledgerwood, A., & Eastwick, P. W. Implicit Bias ≠ Bias on Implicit Measures. Psychological Inquiry 2022, 33, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, P. , Luck, L., O’Reilly, K., & Peters, K. Workplace gender discrimination in the nursing workforce—An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2023, 32, 5693–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J. , Chinman, M., Tharp, A., Baker, J., Flaspohler, P., Fortson, B., Kerr, A., Lamont, A., Meyer, A., Smucker, S., Wargel, K., & Wandersman, A. Development and pilot test of criteria defining best practices for organizational sexual assault prevention. Preventive Medicine Reports 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, L. S. H. , Kerklaan, J., Clarke, S., Kohn, M., Baumgart, A., Guha, C., Tunnicliffe, D. J., Hanson, C. S., Craig, J. C., & Tong, A. Experiences and Perspectives of Transgender Youths in Accessing Health Care: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatrics 2021, 175, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M. , Hinton, J. D. X., & Anderson, J. R. A systematic review of the relationship between religion and attitudes toward transgender and gender-variant people. International Journal of Transgenderism 2019, 20, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. , Xie, H., Huang, Z., Zhang, Q., Wilson, A., Hou, J., Zhao, X., Wang, Y., Pan, B., Liu, Y., Han, M., & Chen, R. The mental health of transgender and gender non-conforming people in China: A systematic review. The Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e954–e969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, D. M. , & Molix, L. Social Stigma and Sexual Minorities’ Romantic Relationship Functioning: A Meta-Analytic Review. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2015, 41, 1363–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, A. , Maudsley, G., & Whitehead, M. The impacts of profound gender discrimination on the survival of girls and women in son-preference countries—A systematic review. Health & Place 2023, 79, 102942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van’t Foort-Diepeveen, R. A. , Argyrou, A., & Lambooy, T. Holistic and integrative review into the barriers to women’s advancement to the corporate top in Europe. Gender in Management: An International Journal 2021, 36, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, N. B. , Bernardi, K., Olavarria, O. A., Shah, P., Dhanani, N., Loor, M., Holihan, J. L., & Liang, M. K. Gender Disparity Among American Medicine and Surgery Physicians: A Systematic Review. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 2021, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogstad, E. T. Gender in eSports research: A literature review. European Journal for Sport and Society 2022, 19, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T. S. , Ali, S. S., Nadeem, S., Memon, Z., Soofi, S., Madhani, F., Karim, Y., Mohammad, S., & Bhutta, Z. A. Perpetuation of gender discrimination in Pakistani society: Results from a scoping review and qualitative study conducted in three provinces of Pakistan. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. , Thompson, J. C., Ringel, N. E., Kim-Fine, S., Ferguson, L. A., Blank, S. V., Iglesia, C. B., Balk, E. M., Secord, A. A., Hines, J. F., Brown, J., & Grimes, C. L. Sexual Harassment, Abuse, and Discrimination in Obstetrics and Gynecology: A Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2410706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmer, C. , Dorn, J., & Mata, J. The immediate effect of discrimination on mental health: A meta-analytic review of the causal evidence. Psychological Bulletin 2024, 150, 215–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, P. P. , & Quezada, L. Associations between microaggression and adjustment outcomes: A meta-analytic and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin 2019, 145, 45–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miano, P. , & Urone, C. What the hell are you doing? A PRISMA systematic review of psychosocial precursors of slut-shaming in adolescents and young adults. Psychology & Sexuality 2024, 15, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, A. , Fontanil, Y., & García-Izquierdo, A. “Why Can’t I Become a Manager?”—A Systematic Review of Gender Stereotypes and Organizational Discrimination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degner, J. , & Dalege, J. The apple does not fall far from the tree, or does it? A meta-analysis of parent–child similarity in intergroup attitudes. Psychological Bulletin 2013, 139, 1270–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, C. , & Hurst, S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics 2017, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M. , See, C., & Ignacio, J. Qualitative systematic review: The lived experiences of males in the nursing profession on gender discrimination encounters. International Nursing Review 2024, 71, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre-Pérez, L. , Oliver-Parra, A., Torres, X., & Bertran, M. J. How do we measure gender discrimination? Proposing a construct of gender discrimination through a systematic scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health 2022, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, G. A. , Puhl, R. M., Taylor, B. A., Zaleski, A. L., Livingston, J., & Pescatello, L. S. Links between discrimination and cardiovascular health among socially stigmatized groups: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0217623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, A. , Orton, L., Nayak, S., Ring, A., Petticrew, M., Sowden, A., White, M., & Whitehead, M. The health impacts of women’s low control in their living environment: A theory-based systematic review of observational studies in societies with profound gender discrimination. Health & Place 2018, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L. , Mari, V., Parini, S., Capelli, G., Tacconi, G., Chessa, A., De Santi, G., Verdi, D., Frigerio, I., Scarpa, M., Gumbs, A., & Spolverato, G. Discrimination Toward Women in Surgery: A Systematic Scoping Review. Annals of Surgery 2022, 276, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurn, P. , Bassett, D. S., & Rust, N. C. The Citation Diversity Statement: A Practice of Transparency, A Way of Life. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2020, 24, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Umbrella Categories | Dimensions | Papers |

| Discrimination manifestation | Structural and overt discrimination | [16,20,22,24,25] |

| Interpersonal and subtle discrimination | [16,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] | |

| Implicit biases and stereotyping mechanisms | [14,17,20,21,24,29,30,31,32] | |

| Health and professional outcomes | Mental health consequences | [16,18,19,26,33] |

| Physical health implications | [16,20,24,34,35] | |

| Professional and social functioning | [14,19,21,22,24,25,29,31,32,35,36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).