1. Introduction: Microplastics as Disruptive Structures of Biological Systems

Microplastics (MPs), consisting of plastic particles, fibers, and films with a diameter of less than 5 mm, can persist in the environment for extended periods [

1]. Humans can be exposed to them through inhalation of airborne particles, ingestion of contaminated food and water via the food chain [

2], or dermal contact [

3].

In vitro studies on the effects of MPs in mammals have demonstrated their potential to induce cytotoxic, inflammation, genotoxicity, oxidative stress, embryotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and carcinogenicity. Similarly,

in vivo studies in rodents have confirmed the bioaccumulation of MPs in various organs, including the liver, spleen, kidney, brain, lungs, and intestines, which is associated with reproductive toxicity and transgenerational effects [

4].

MPs have also been detected in various human fluids and tissues, including feces [

2], urine [

5], sputum [

6], blood [

7], thrombi [

8], placenta [

9], lung tissue [

10], intestines [

11], and liver [

12]. Raman spectroscopy was the primary detection method used in most of these studies. The evidence suggests that MPs may enter the body through translocation mechanisms that are not yet fully understood [

13]. While some particles may be eliminated through biological processes, a fraction can persist in organs for extended periods, triggering the release of inflammatory cytokine. Additionally, compromised immunological and systemic conditions may contribute to the increased accumulation of MPs in specific tissues [

12].

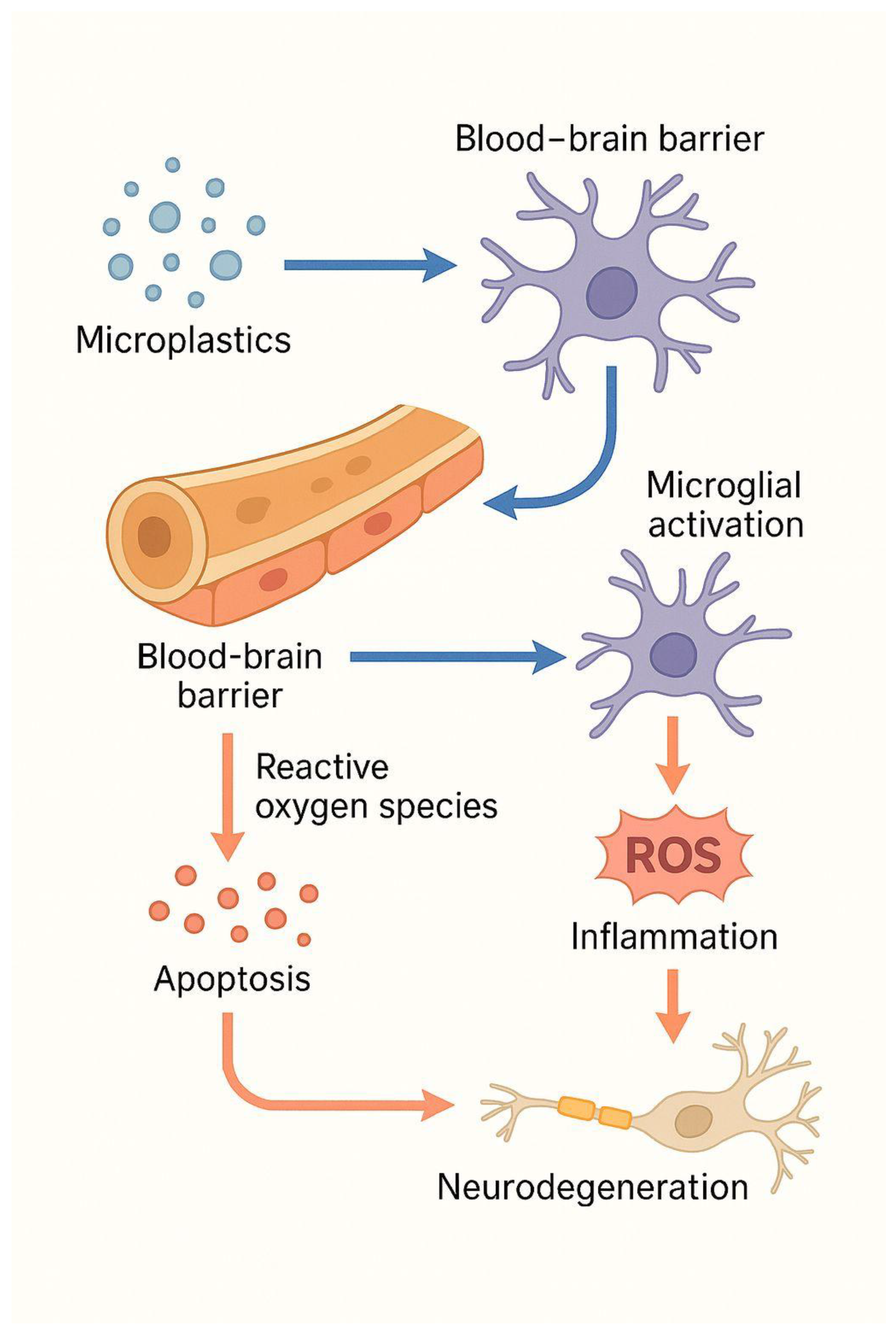

Tissues that function as physiological barriers to specialized organs can also be compromised, allowing MPs to cross. This has been demonstrated in studies showing MPs deposits traversing the hematotesticular [

14], intestinal, alveolo-capillary [

3], and placental barriers [

13]. In the central nervous system (CNS), the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a complex structure that plays a crucial role in maintaining neuronal homeostasis by selectively regulating molecular permeability. When this function is disrupted, cellular infiltration occurs, accompanied by aberrant molecular signaling and impaired clearance [

15].

The fragmentation of MPs into nanoplastics (NPs), defined as particles smaller than 1 μm [

16], raises particular concern due to their potential harm to biological systems. Studies suggest that NPs originating from cosmetic products, when ingested orally at sizes smaller than 100 nm, can reach the brain and induce neurotoxicity [

17]. This phenomenon has been observed in both aquatic and mammalian model organisms [

18]. Although there are no reports confirming the presence of MPs or NPs in the human brain, studies in terrestrial animals indicate that these particles can accumulate in brain structures and interact with microglial cells, a key component of neuroglia [

19].

Neuroglia comprises the non-neuronal cell types of the central, peripheral, enteric, and autonomic nervous systems, accounting for nearly half of the total volume of the human brain. Although their proportion varies across brain regions, individuals, and animal species, neuroglia plays critical roles in regulating ionic, neurotransmitter, and metabolite concentrations, defending against microbial agents and cellular debris, and producing myelin. These functions are essential for preventing neuropathological conditions [

20]. Glial cells are categorized into astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes (OLs), and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), each with specialized functions that collectively sustain synaptic integrity in the brain [

21].

This review examines the effects of MPs on neuroglia, cells with complex and essential functions, synthesizing findings from 18 studies that used both in vitro and in vivo experimental models. Understanding the interactions between MPs and neuroglial cells is crucial to elucidate their potential role as emerging environmental neurotoxicants that can disrupt neural homeostasis and contribute to the onset of neurodegenerative processes.

2. Microplastics and Neurodegenerative Diseases

Previous studies have reported the impact of exposure to plastics, which have a complex chemical composition, and to the associated chemical substances [

22]. MPs have been shown to induce oxidative stress, inflammation, and possible epigenetic modifications. Additionally, MPs have been linked to various health issues, including the onset of hepatic cirrhosis [

12], the development of neurodegenerative diseases [

17], infertility due to damage to male and female gonads [

23], and diarrheal diseases [

24]. MPs have also been found to exert both promoting and suppressive effects on cancer cells [

25] and have been associated with endothelial injury in the context of cerebrovascular accidents [

26]. This review focuses on the impact of MPs on neuroglia.

In the CNS, MPs may disrupt neuronal functions [

18], altering the interactions among different types of glial cells. These alterations include impaired glia-neuron metabolic coupling, neuroinflammation, and protein aggregation, which contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by progressive loss of neuronal structure and function [

27].

In Alzheimer's disease [

28], pyroptosis has been observed in BV2 microglial cell lines, which express nuclear oncogenes v-myc, cytoplasmic oncogenes v-raf, and the surface antigen env gp70. Similarly, pyroptosis has been detected in the adherent, tumorigenic RAW264.7 cell line [

28], a model used to investigate the activation of MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways in macrophages. This activation leads to the overexpression of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), providing further insight into immune dysfunction mechanisms [

29], particularly after GSDMD gene silencing [

28].

Other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, are also associated with neuroinflammatory processes regulated by microglia and astrocytes. Studies have shown that the activation of these cells can be neurotoxic (M1 microglia and A1 astrocytes) or neuroprotective (M2 microglia and A2 astrocytes), depending on the surrounding environment and the stimulus involved [

30]. MPs, particularly polystyrene NPs, are among the factors capable of inducing such activation. In a study, oral administration of these materials at doses ranging from 0.5 to 50 mg/kg of body weight for seven days significantly increased blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability and promoted dose-dependent accumulation in the brains of mice. This led to microglial activation and neuronal damage. In the same study, in vitro experiments with immortalized human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3) showed that MPs internalized into cells, induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, activated nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), triggered TNF-α secretion, and caused necroptosis of hCMEC/D3 cells. Additionally, these particles disrupted tight junctions by decreasing occludin expression and activating murine BV2 microglial cells [

31].

Microglia require functional balance to maintain homeostasis. Studies have demonstrated that polystyrene microplastics (PS-MPs) deposited in microglial cells of mouse brains after oral administration of three types of fluorescent PS-MPs (0.2, 2, and 10 μm) cause morphological changes, immune alterations, and microglial apoptosis induced by phagocytosis of the 0.2- and 2-μm particles. Similar alterations were observed in the expression of microglial differentiation markers, NF-κB activation, increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, and apoptotic markers in both human microglial cells treated with PS-MPs and mouse brain tissue. These findings suggest that smaller PS-MPs pose a significant risk by promoting microglial immune activation and apoptosis in murine and human brains [

19]. Microglial apoptosis plays a crucial role in responding to injury, infection, and cellular debris clearance, as well as maintaining homeostasis. Its susceptibility appears to be influenced by factors such as sex, developmental stage, and local microenvironment, which should be considered in future research approaches [

32].

Neurodegenerative diseases associated with cognitive decline may be triggered or exacerbated by environmental factors, including exposure to NPs, which can induce excessive microglial activation and a neuroinflammatory response. These alterations may vary depending on particle morphology, chronic exposure, particle size, and the combination of various microplastic types and exposure routes [

17]. A study in male mice, in which synthesized NPs were administered at doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg/day for seven weeks, found that the particles, once internalized, activated microglia, and triggered inflammatory responses, ultimately leading to hippocampal dysfunction [

17].

3. Possible Mechanisms Involved in the Development of Neurodegenerative Diseases Induced by Microplastics

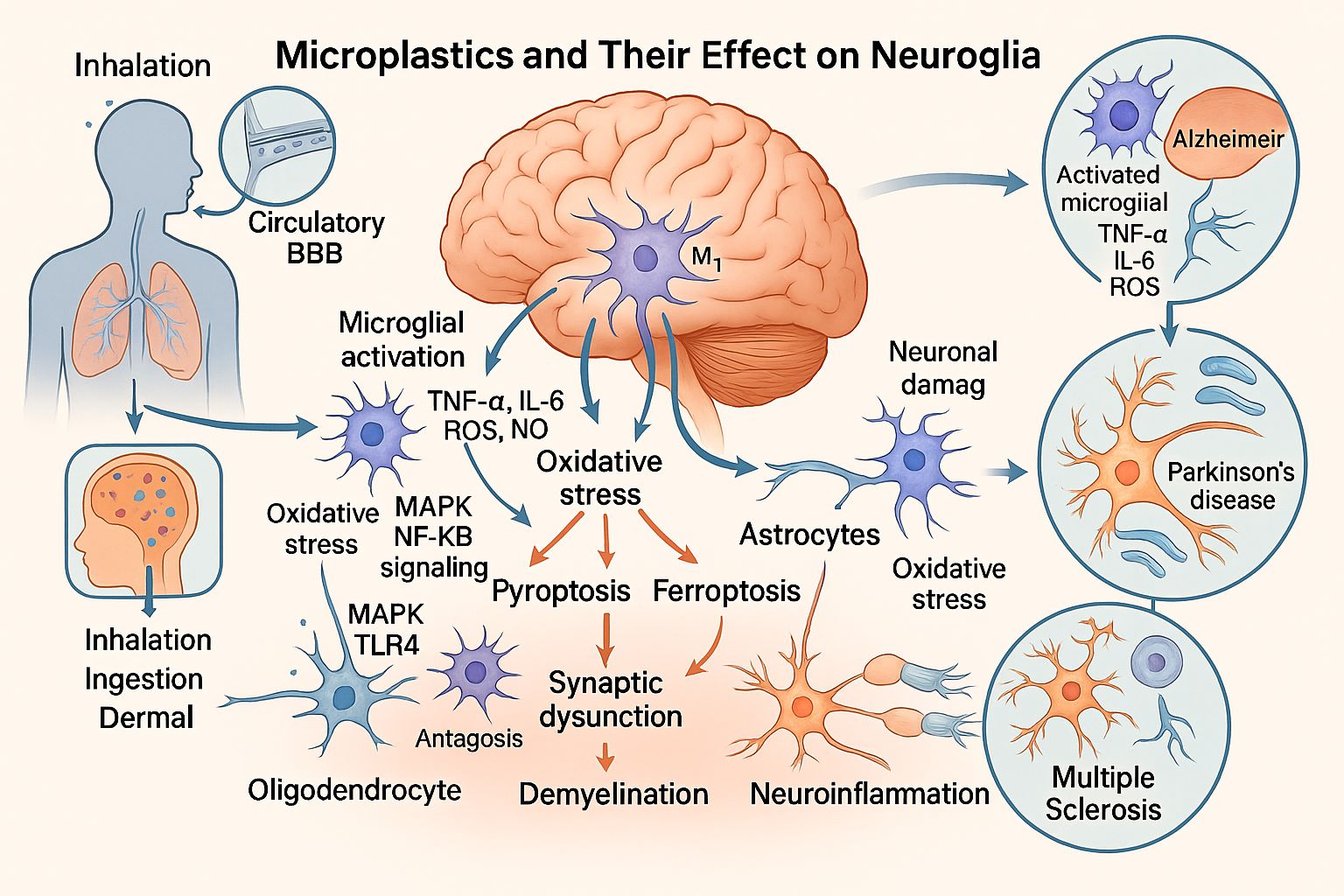

Previous studies have identified mechanisms involved in the development of diseases potentially caused by exposure to MPs and NPs (

Table 1).

A growing body of experimental evidence links exposure to MPs and NPs with several neurodegenerative diseases through distinct but overlapping mechanisms of neurotoxicity.

Research has shown that MPs and NPs can trigger Alzheimer's-like pathology through various mechanisms. Studies have found that polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs) can induce microglial activation and memory impairment, mimicking the pathology of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases [

17]. In contrast, PS-MPs have been shown to trigger microglial phagocytosis and immune dysregulation, contributing to the development of Alzheimer's disease and multiple sclerosis [

19]. Furthermore, exposure to PS-MPs has been linked to microglial pyroptosis and cognitive decline, hallmark features of Alzheimer's disease [

28]. Other research has demonstrated that PS-NPs can penetrate the BBB, activate microglia, and promote Alzheimer's and Parkinson's-related changes [

31]. Additionally, studies have revealed that NPs exposure can lead to proteomic changes in brain tissue [

38], activation of the JNK/HO-1/FTH1 signaling pathway and associated inflammation and ferroptosis [

39], and accumulation of NPs in fetal rat brains, resulting in myelin damage [

40]. Moreover, the accumulation of MPS after cerebral ischemia has been shown to cause neuronal death, suggesting a potential degenerative mechanism linked to Alzheimer's disease [

45].

Similar pathophysiological mechanisms have been implicated in Parkinson's disease models. Research has shown that NPS exposure can activate the JNK/HO-1/FTH1 signaling pathway, leading to ferroptosis and neuroinflammation [

39]. A recent study found that PS-NPs can exacerbate dopaminergic neurodegeneration through the gut-brain axis, worsening Parkinson's pathology [

46]. Furthermore, studies have consistently reported microglial activation, synaptic dysfunction, and oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease models, resulting in neuronal damage [

17,

31,

33].

Evidence suggests that microglial and astrocytic activation are key targets of MPs toxicity. Studies have linked polystyrene microplastics to immune dysregulation and glial activation [

19], while research on NPs has shown that they can activate a TLR4/p38-mediated proinflammatory pathway, leading to demyelination and glial overactivation, similar to the pathology observed in multiple sclerosis [

37].

Additional studies have identified broader, or early-stage neurotoxic mechanisms associated with MPs exposure. Research has shown that PS-NPs can cause neurotoxicity and genetic damage in marine invertebrates [

34]. Furthermore, exposure to MPs has been linked to abnormal expression of neurodevelopmental genes and neuronal apoptosis in larvae, indicating developmental neurotoxicity [

35]. Another study found that polyethylene MPs can cause neurotoxicity, but supplementation with Lycopene, Citric Acid, and Chlorella significantly mitigated these effects [

36].

Microplastic exposure has been linked to a range of neurotoxic effects and underlying mechanisms. Recent findings include activation of the lung-brain axis and microglial reactivity as mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction [

41]. Additionally, NPs have been shown to disrupt hippocampal synaptogenesis, leading to anxiolytic-like behavior and spatial memory loss [

42]. PS-NPs have also been found to be internalized by human neural stem cells, causing cytotoxicity [

43]. Another study revealed that polystyrene nanoparticles accumulate in astrocytes, implicating them in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [

44].

These eighteen studies collectively reveal that MPS, and NPs induce a range of neurotoxic effects, including microglial activation, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, ferroptosis, and synaptic dysfunction, which converge to contribute to the pathogenesis of various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, ALS, and related neurological disorders.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanisms by which microplastics damage neuroglia.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanisms by which microplastics damage neuroglia.

4. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

The cumulative evidence shows that MPs, and NPs are biologically active pollutants that can cause significant neurotoxic effects. Upon internalization, these particles can cross physiological barriers, including the blood-brain barrier, triggering microglial activation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators. These mechanisms collectively lead to neuronal apoptosis, synaptic alterations, and impaired neuroglial communication, processes that are characteristic of major neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The overlap of these molecular pathways suggests that chronic exposure to MPs and NPs may be a previously underappreciated environmental factor contributing to neurodegeneration.

Despite consistent findings in in vitro and in vivo experimental models, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding microplastic accumulation and their long-term neurobiological consequences in humans. Although MPs have been confirmed in various human tissues and fluids, their direct detection in the human brain has not yet been achieved. Furthermore, the impact of particle size, morphology, surface chemistry, and exposure duration on neurotoxic potential remains poorly characterized. The interaction between MPs and co-occurring environmental toxicants, such as heavy metals and endocrine disruptors, may further exacerbate their adverse effects through synergistic mechanisms that are not yet fully understood.

Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms by which MPs and NPs interact with neural and glial cells, utilizing advanced imaging, omics technologies, and single-cell analysis. Longitudinal and epidemiological studies are needed to evaluate behavioral and cognitive outcomes following chronic low-dose exposure, reflecting realistic environmental scenarios. Additionally, the development of improved detection methods, such as Raman spectroscopy, pyrolysis-GC/MS, and hyperspectral imaging, will be essential for identifying and quantifying MPs in neural tissues. Preventive strategies should also include the promotion of biodegradable materials, stricter environmental regulations, and therapeutic interventions aimed at mitigating oxidative and inflammatory damage.

Microplastics represent an emerging class of environmental neurotoxicants capable of disrupting neural homeostasis and triggering molecular events characteristic of neurodegenerative processes. Their pervasive presence in the environment, combined with the growing evidence of their systemic effects, underscores an urgent need for interdisciplinary research integrating neuroscience, toxicology, and environmental health. Understanding the neurobiological impact of microplastic exposure will be critical to redefining environmental determinants of neurodegenerative disease and guiding future public health and environmental protection strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C.-M. and C.M.-T.; investigation, E.C.-M., C.M.-T., V.M.-T., C.S.-M., N.D. and I.G.-P.; resources, C.M.-T. and E.C.-M.; writing original draft preparation, C.M.-T.,E.C.-M., and N.D., writing – review and editing, E.C.-M., C.M.-T., V.M.-T., C.S.-M., N.D. and I.G.-P.; funding acquisition, E.C.-M. and C.M.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A1 |

Neurotoxic astrocyte phenotype |

| A2 |

Neuroprotective astrocyte phenotype |

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| ALS |

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| BBB |

Blood Brain Barrier |

| BV2 |

Murine microglial cell line (Balc/c-derived immortalized microglia) |

| CNS |

Central Nervous System |

| FTH1 |

Ferritin Heavy Chain 1 |

| GFAP |

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| GSDMD |

Gasdermin D |

| hCMEC/D3 |

Human Cerebral Microvascular Endothelial Cells (immortalized line) |

| HO-1 |

Heme Oxygenase 1 |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| JNK |

c-Jun N-terminal Kinase |

| M1 |

Proinflammatory microglial phenotype |

| M2 |

Antiinflammatory microglial phenotype |

| MAPK |

Mitogen activated protein kinase |

| MPs |

Microplastics |

| MS |

Multiple Sclerosis |

| NF-kB |

Nuclear Factor kappa B |

| NPs |

Nanoplastics |

| OCs/TJs |

Tight junctions |

| OLs |

Oligodendrocytes |

| OPCs |

Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells |

| PD |

Parkinson’s disease |

| PS-MPs |

Polystyrene Microplastics |

| RAW264.7 |

Murine macrophage cell line |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TLR4 |

Toll-like Receptor 4 |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

References

- Zhao B, Rehati P, Yang Z, Cai Z, Guo C, Li Y. The potential toxicity of microplastics on human health. Sci Total Environ. 2024;912:168946. [CrossRef]

- Cho YM, Choi KH. The current status of studies of human exposure assessment of microplastics and their health effects: a rapid systematic review. Environ Anal Health Toxicol. 2021;36(1):e2021004. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y, Tu C, Li R, et al. A systematic review of the impacts of exposure to micro- and nano-plastics on human tissue accumulation and health. Eco Environ Health. 2023;2(4):195-207. [CrossRef]

- Xu JL, Lin X, Wang JJ, Gowen AA. A review of potential human health impacts of micro- and nanoplastics exposure. Sci Total Environ. 2022;851(Pt 1):158111. [CrossRef]

- Pironti C, Notarstefano V, Ricciardi M, Motta O, Giorgini E, Montano L. First Evidence of Microplastics in Human Urine, a Preliminary Study of Intake in the Human Body. Toxics. 2022;11(1):40. [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Huang X, Bi R, et al. Detection and Analysis of Microplastics in Human Sputum. Environ Sci Technol. 2022;56(4):2476-2486. [CrossRef]

- Leslie HA, van Velzen MJM, Brandsma SH, Vethaak AD, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, Lamoree MH. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ Int. 2022;163:107199. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Feng Y, Wang R, et al. Pigment microparticles and microplastics found in human thrombi based on Raman spectral evidence. J Adv Res. 2023;49:141-150. [CrossRef]

- Ragusa A, Svelato A, Santacroce C, et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ Int. 2021;146:106274. [CrossRef]

- Amato-Lourenço LF, Carvalho-Oliveira R, Júnior GR, Dos Santos Galvão L, Ando RA, Mauad T. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J Hazard Mater. 2021;416:126124. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim YS, Tuan Anuar S, Azmi AA, et al. Detection of microplastics in human colectomy specimens. JGH Open. 2020;5(1):116-121. [CrossRef]

- Horvatits T, Tamminga M, Liu B, et al. Microplastics detected in cirrhotic liver tissue. EBioMedicine. 2022;82:104147. [CrossRef]

- Medley EA, Spratlen MJ, Yan B, Herbstman JB, Deyssenroth MA. A Systematic Review of the Placental Translocation of Micro- and Nanoplastics. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2023;10(2):99-111. [CrossRef]

- Marcelino RC, Cardoso RM, Domingues ELBC, Gonçalves RV, Lima GDA, Novaes RD. The emerging risk of microplastics and nanoplastics on the microstructure and function of reproductive organs in mammals: A systematic review of preclinical evidence. Life Sci. 2022;295:120404. [CrossRef]

- Cruz JVR, Batista C, Diniz LP, Mendes FA. The Role of Astrocytes and Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuroglia. 2023;4(3):209-221. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Zhang B, Yao Q, et al. Toxicological effects of micro/nano-plastics on mouse/rat models: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health. 2023;11:1103289. [CrossRef]

- Paing YMM, Eom Y, Song GB, et al. Neurotoxic effects of polystyrene nanoplastics on memory and microglial activation: Insights from in vivo and in vitro studies. Sci Total Environ. 2024;924:171681. [CrossRef]

- Prüst M, Meijer J, Westerink RHS. The plastic brain: neurotoxicity of micro- and nanoplastics. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2020;17(1):24. Published 2020 Jun 8. [CrossRef]

- Kwon W, Kim D, Kim HY, et al. Microglial phagocytosis of polystyrene microplastics results in immune alteration and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Sci Total Environ. 2022;807(Pt 2):150817. [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky A, Ho MS, Zorec R, Parpura V. The Concept of Neuroglia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1175:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Shen X, Zhang Y, et al. Interactions of glial cells with neuronal synapses, from astrocytes to microglia and oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Glia. 2023;71(6):1383-1401. [CrossRef]

- Symeonides C, Aromataris E, Mulders Y, et al. An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses Evaluating Associations between Human Health and Exposure to Major Classes of Plastic-Associated Chemicals. Ann Glob Health. 2024;90(1):52. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Meng J, Tian J, et al. Reproductive and developmental implications of micro- and nanoplastic internalization: Recent advances and perspectives. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024;286:117245. [CrossRef]

- Nwanaforo E, Obasi CN, Frazzoli C, Bede-Ojimadu O, Orisakwe OE. Exposure to Environmental Pollutants and Risk of Diarrhea: A Systematic Review. Environ Health Insights. 2024;18:11786302241304539. [CrossRef]

- Baspakova A, Zare A, Suleimenova R, et al. An updated systematic review about various effects of microplastics on cancer: A pharmacological and in-silico based analysis. Mol Aspects Med. 2025;101:101336. [CrossRef]

- Arba F, Rinaldi C, Caimano D, Vit F, Busto G, Fainardi E. Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and Hemorrhagic Transformation in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol. 2021;11:594613. [CrossRef]

- Dar NJ, Bhat JA, John U, Bhat SA. Neuroglia in Neurodegeneration: Exploring Glial Dynamics in Brain Disorders. Neuroglia. 2024;5(4):488-504. [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Lin Y, Shen H. Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics Promotes the Progression of Cognitive Impairment in Alzheimer's Disease: Association with Induction of Microglial Pyroptosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2024;61(2):900-907. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Chen X, Xuan Y, et al. Surface functionalization-dependent inflammatory potential of polystyrene nanoplastics through the activation of MAPK/ NF-κB signaling pathways in macrophage Raw 264.7. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023;251:114520. [CrossRef]

- Kwon HS, Koh SH. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl Neurodegener. 2020;9(1):42. [CrossRef]

- Shan S, Zhang Y, Zhao H, Zeng T, Zhao X. Polystyrene nanoplastics penetrate across the blood-brain barrier and induce activation of microglia in the brain of mice. Chemosphere. 2022;298:134261. [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi IR, Bordt EA. Sex and Region-Specific Differences in Microglial Morphology and Function Across Development. Neuroglia. 2025;6(1):2. [CrossRef]

- Jung BK, Han SW, Park SH, Bae JS, Choi J, Ryu KY. Neurotoxic potential of polystyrene nanoplastics in primary cells originating from mouse brain. Neurotoxicology. 2020;81:189-196. [CrossRef]

- Deidda I, Russo R, Bonaventura R, Costa C, Zito F, Lampiasi N. Neurotoxicity in Marine Invertebrates: An Update. Biology (Basel). 2021;10(2):161. [CrossRef]

- Zhou R, Yang H, Zhou D, et al. Interactive neurotoxicity of environmentally relevant concentrations of polystyrene nanoplastics and butyl methoxydibenzoyl methane on early zebrafish embryos. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022;9:1099984. [CrossRef]

- Hamed M, Soliman HAM, Eid Z, et al. Dietary Feeding Lycopene, Citric Acid, and Chlorella Alleviated the Neurotoxicity of Polyethylene Microplastics in African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Front. Environ. Sci. 2022;10:869727. [CrossRef]

- Antunes J, Sobral P, Martins M, Branco V. Nanoplastics activate a TLR4/p38-mediated pro-inflammatory response in human intestinal and mouse microglia cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2023;104:104298. [CrossRef]

- Kim HY, Ashim J, Park S, et al. A preliminary study about the potential risks of the UV-weathered microplastic: The proteome-level changes in the brain in response to polystyrene derived weathered microplastics. Environ Res. 2023;233:116411. [CrossRef]

- Sun J, Wang Y, Du Y, et al. Involvement of the JNK/HO-1/FTH1 signaling pathway in nanoplastic-induced inflammation and ferroptosis of BV2 microglia cells. Int J Mol Med. 2023;52(1):61. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Tian L, Chen J, et al. Selective bioaccumulation of polystyrene nanoplastics in fetal rat brain and damage to myelin development. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024;278:116393. [CrossRef]

- Kang H, Huang D, Zhang W, et al. Pulmonary Flora-Derived Lipopolysaccharide Mediates Lung-Brain Axis through Activating Microglia Involved in Polystyrene Microplastic-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(47):e2404966. [CrossRef]

- Tian L, Zhang Y, Chen J, et al. Effects of nanoplastic exposure during pregnancy and lactation on neurodevelopment of rat offspring. J Hazard Mater. 2024;474:134800. [CrossRef]

- González-Caballero MC, de Alba González M, Torres-Ruiz M, et al. Internalization and toxicity of polystyrene nanoplastics on inmortalized human neural stem cells. Chemosphere. 2024;355:141815. [CrossRef]

- Adamiak K, Sidoryk-Węgrzynowicz M, Dąbrowska-Bouta B, Sulkowski G, Strużyńska L. Primary astrocytes as a cellular depot of polystyrene nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):6502. [CrossRef]

- Kim DY, Park MK, Yang HW, et al. Effects of Microplastic Accumulation on Neuronal Death After Global Cerebral Ischemia. Cells. 2025;14(4):241. [CrossRef]

- Liang X, Huang G, Wang Y, et al. Polystyrene Nanoplastics Hitch-Hike the Gut-Brain Axis to Exacerbate Parkinson's Pathology. ACS Nano. 2025;19(5):5475-5492. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Most common microplastics and Mechanisms involved in disease.

Table 1.

Most common microplastics and Mechanisms involved in disease.

| Country |

Microplastics type |

Mechanisms involved |

Disease |

| Korea [17] |

Polystyrene nanoplastics |

Microglial activation, memory impairment |

Alzheimer's, Parkinson's |

| Korea [19] |

Polystyrene microplastics |

Microglial phagocytosis, immune alteration |

Alzheimer's, Multiple Sclerosis |

| China [28] |

Polystyrene microplastics |

Microglial pyroptosis, cognitive impairment |

Alzheimer's |

| China [31] |

Polystyrene nanoplastics |

Blood-brain barrier penetration, microglial activation |

Alzheimer's, Parkinson's |

| Korea [33] |

Polystyrene nanoplastics |

Neurotoxic potential, damage to primary brain cells |

Alzheimer's, Parkinson's |

| Italy [34] |

Polystyrene nanoplastics |

Neurotoxicity in marine invertebrates |

Gene

Damage |

| China [35] |

Polystyrene nanoplastics |

Neurotoxicity, abnormal expression of developmental

genes neurogenin 1, glial fibrillary acidic protein |

Neuronal

apoptosis and behavioral abnormalities in larvae |

| Egypt [36] |

Polyethylene microplastics |

Neurotoxicity alleviated by Lycopene, Citric Acid, Chlorella |

Alzheimer's, Parkinson's |

| Portugal [37] |

Nanoplastics |

TLR4/p38-mediated pro-inflammatory response |

Alzheimer's, Multiple Sclerosis |

| Korea [38] |

Polystyrene microplastics |

Proteome-level changes in brain |

Alzheimer's |

| China [39] |

Nanoplastics |

JNK/HO-1/FTH1 signaling pathway, inflammation, ferroptosis |

Alzheimer's, Parkinson's |

| China [40] |

Polystyrene nanoplastics |

Bioaccumulation in fetal rat brain, myelin development damage |

Alzheimer's, Parkinson's |

| China [41] |

Polystyrene microplastics |

Lung-brain axis activation, microglial activation |

Alzheimer's, Cognitive dysfunction |

| China [42] |

Nanoplastics |

Effects on the formation of hippocampal

synapses |

Anxiolytic-like behaviors and decreased spatial memory |

| Spain [43] |

Polystyrene nanoplastics |

Internalization and toxicity on immortalized human neural stem cells |

Alzheimer's |

| Poland [44] |

Polystyrene nanoparticles |

Cellular depot in astrocytes |

Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, ALS |

| Korea [45] |

Microplastics |

Neuronal death after global cerebral ischemia |

Alzheimer's |

| China [46] |

Polystyrene nanoplastics |

Gut-brain axis to exacerbate Parkinson's pathology |

Parkinson's |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).