1. Introduction

With the development of human civilization, plastic pollution has caused serious ecological and health problems [

1]. Waste plastics can be broken down into polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs) with a diameter of less than 1000 nm through various physical and chemical processes. Microplastics, defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 mm, include a subset known as nanoplastics(<100 nm), which are less than 1 μm in size [

2,

3,

4]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most widespread neurodegenerative disease and a major cause of dementia among the elderly. The main pathological features include intracellular aggregates containing phosphorylated tau protein that form neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and extracellular deposits of amyloid-β (Aβ) that induce the formation of senile plaques [

5]. Polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs) can damage the central nervous system through the blood-brain barrier (BBB). However, it is still unclear whether exposure to PS-NPs contributes to BBB disruption and the underlying mechanisms [

6].

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) in the brain, primarily due to the overexpression of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and beta-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1). Additionally, reduced activity of Aβ-degrading enzymes such as neprilysin (NEP) and insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), as well as impaired Aβ transport across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCB), contribute to Aβ accumulation. Transport proteins such as low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) play crucial roles in Aβ transport across these barriers and have been associated with AD pathology [

7,

8].

When nanoparticles (NPs) reach brain regions, they can stimulate inflammatory responses and oxidative stress, which are considered common denominators of CNS diseases

[9]. Therefore, many studies have been devoted to explaining the neurotoxic effects of various NP components and their association with CNS diseases. It is widely known that β-amyloid (Aβ) plays an important role in the development of AD. Misprocessing of Aβ peptides in the brain leads to amyloidogenic Aβ peptides and amyloid plaques. Amyloid plaques can activate glial cells, leading to the release of inflammatory mediators

[10]. Epidemiological studies suggest that exposure to air pollution may be associated with the accumulation of Aβ in the brains of humans and dogs

[11], but the molecular mechanisms by which NPs regulate Aβ levels in the brain are currently unknown. Although the pathways by which NPs enter the brain through the bloodstream are not yet clearly understood, recent studies have proposed hypotheses related to the disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [

12,

13].

In recent years, awareness and concern about the potential impact of microplastic exposure on human health have been increasing. Recent studies have found that microplastics, as environmental pollutants, can activate microglial pyroptosis, promoting the progression of cognitive impairment in Alzheime

r’s disease, and that inhibiting pyroptosis can antagonize the effects of PS. These findings may help to better understand the relationship between environmental pollution and AD. However, it is still unclear whether microplastics are the exact cause of AD, and more research is needed

[14].

2. Materials and Methods

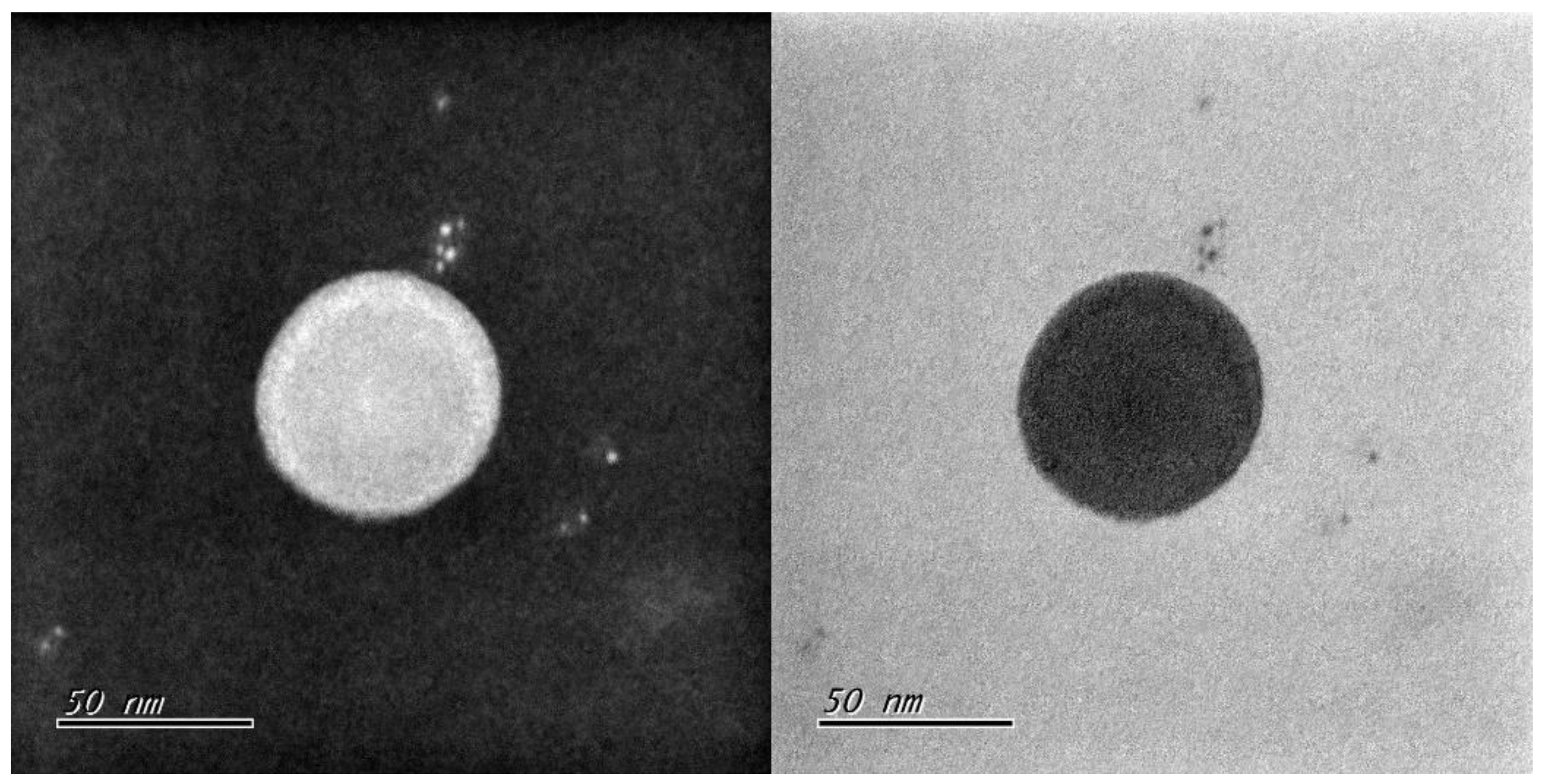

2.1. Polystyrene Microplastics

The polystyrene nanoplastics (50 nm) were obtained from HCT, Co.Ltd (Icheon, Republic of Korea). It was a cer-tified reference material (CRM) with an ISO 17034 certificate. Completely spherical poly-styrene monodisperse particles are manufactured through radical polymerization, and only the final qualified products are sold after undergoing homogeneity and stability evaluation according to ISO Guide 35, and are officially registered with COMAR, the In-ternational Center for Standard Materials. The certified values of HCT Polystyrene certified standard materials have been traceable to METAS (Federal Institute of Metrology), the Swiss national measurement institute. To investigate the self-assembled struc-tures in aqueous solution, a drop of each sample solution was placed on a carbon-coated copper grid [Carbon Type B (15–25 nm) on 200 mesh, with Formvar; Ted Pella, Inc.], and the solution was allowed to evaporate under ambient conditions.These samples were stained by depositing a drop of uranyl acetate aqueous solution (0.4 wt %) on the surface of the sample-loaded grid. The dried specimen was observed using a Hitachi H-7100 op-erated at 100 kV (

Figure 1).

2.2. Cell Culture

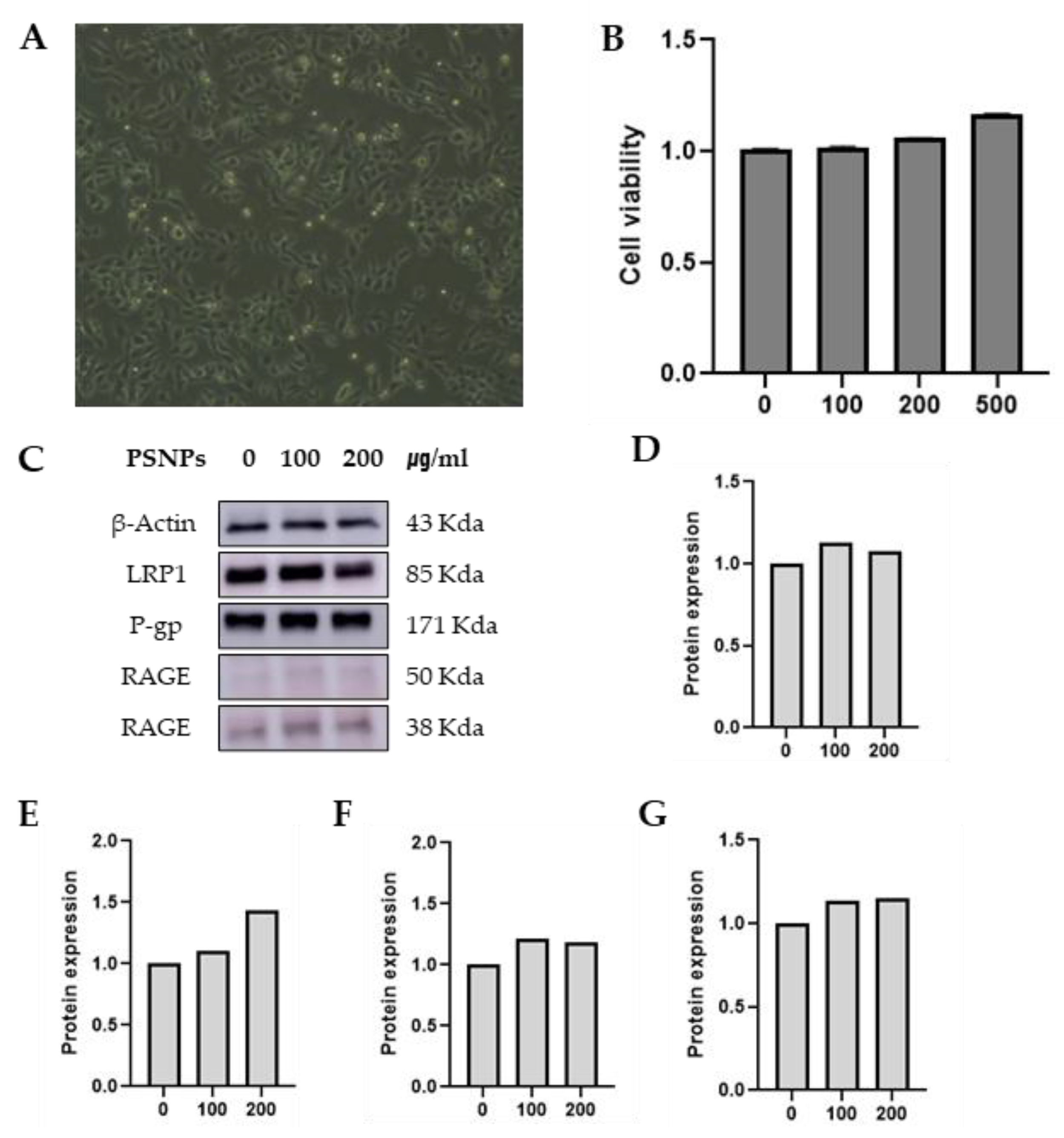

RBE4 Cell

RBE4 cells are the main cells that constitute the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Rat brain endothelial (RBE4) cells were provided by Dr. Wei Zheng (School of Health Sciences, Purdue University). Cells were maintained in a medium containing a 1 : 1 mixture of α-MEM (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) and DMEM/F-12 (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) supplemented with 10 % (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Welgene, Daegu, Korea), 1 % penicillin-streptomycin (PS) (Welgene, South Korea) and 1 ng/ml bFGF (Cell Signaling, MA, USA) at 37 ℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO₂. (

Figure 2a).

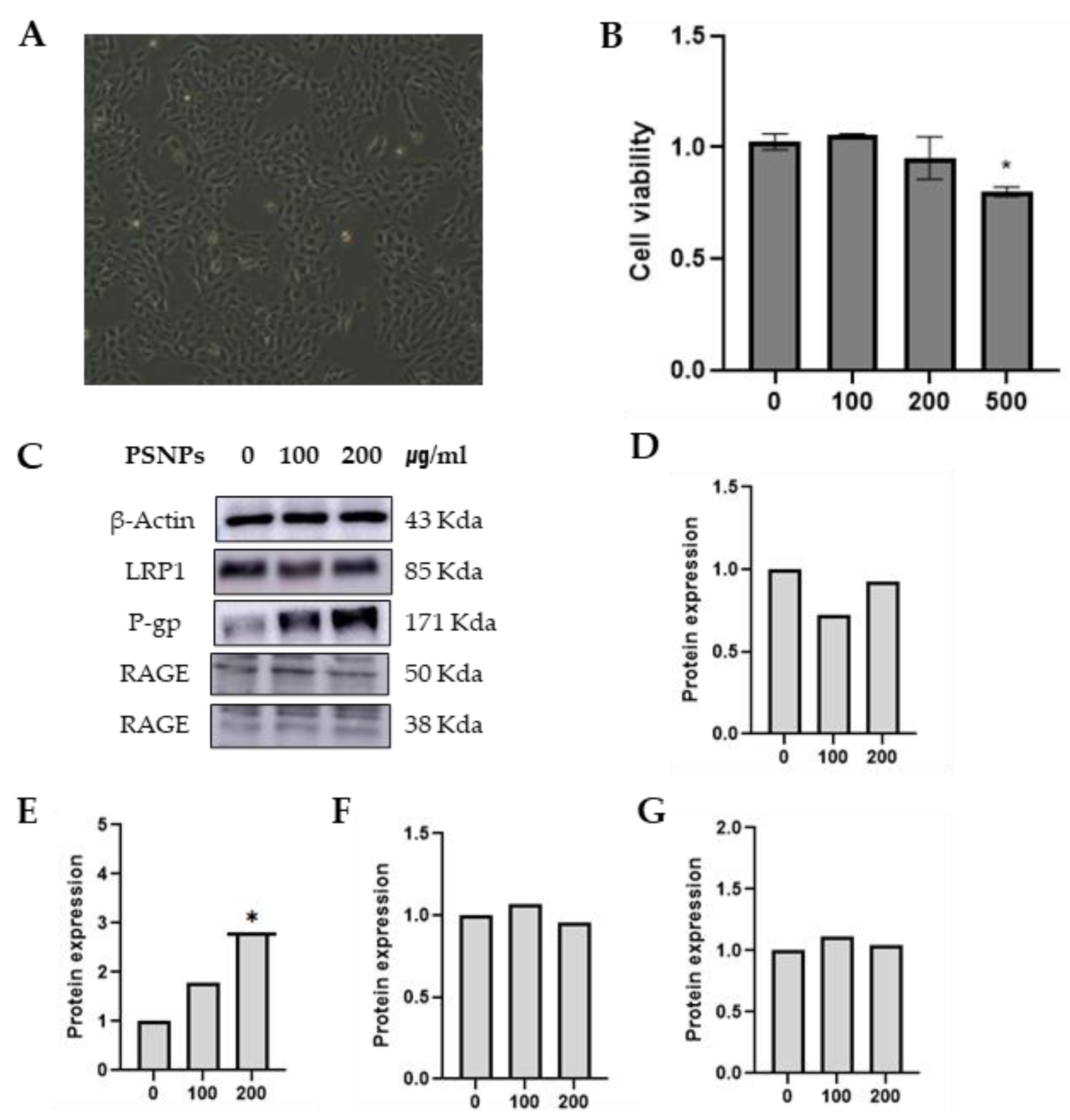

Z310 Cell

Z310 cells are the main cells that constitute the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCB). Rat choroidal epithelial (Z310) cell were provided by Dr. Wei Zheng (School of Health Sciences, Purdue University). Cells were grown in a Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) high glucose medium (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) supplemented with 10 % (v/v) FBS (Welgene, Daegu, Korea), 1 % PS (Welgene, South Korea) and 40 μg/ml Gentamicin (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) at 37 ℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO₂. (

Figure 2b)

2.3. Treatment PSNP

When needed, surfactant removal was performed using a 0.5–3 mL dialysis cassette with a 2,000 molecular weight cutoff (Slide-A-Lyzer®, Thermo Scientific, USA). Each dialysis cassette was filled with 3 mL of PSNP suspension and dialyzed against 1000 mL of DPBS for at least 18 h under continuous stirring at room temperature. The dialysis was conducted in three consecutive steps with renewal of the purification fluid in between.

2.4. Cell Viability

To determine the viability of RBE4 cells and Z310 cells, wst-8 assay was performed. Briefly, cells were seeded at 100 μl (5x10⁴ cells/well) with culture medium in falcon 96-well microplates. After 24 hours, the cells were treated with different concentration of PSNP in culture medium at 37 ℃ and 5 % CO₂ for 24 hours. Following, the cells were incubated MTT reagent (Quanti-Max™ WST-8 Cell Viability Assay Kit (Cat. QM1000) of 10 μl was added to each well and measured in a microplate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm.(Reference control 600-650 nm)

2.5. Western Blot

Total protein was extracted from cultured cells to use western blotting. Cells were incubated with RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific, Cat. 89900) for 20 minutes at 4 ℃ and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 mins at 4 ℃. Protein concentration was determined with BCA Asaay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of protein (10 μg) were loaded to Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel on a 12 % gel and subsequently transferred to PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare, USA). The membranes were blocked 5 % BSA in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1 % Tween 20 for 1 hours at room temperature. After blocking, the membranes were incubated in the primary antibodies; rabbit anti-LRP1 (1 : 50,000, Abcam, #EPR3724, Cambridge, UK), rat anti-RAGE (1 : 250, R&D systems #MAB1179, Minneapolis, MN, USA), rabbit anti-P-glycoprotein (1 : 50,000, Abcam, #ab170904, Cambridge, UK), for overnight at 4 ℃. HRP-conjugated - 10 -goat anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 2,500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad , CA, USA), goat anti-rat (1 : 500, R&D systems) were used as secondary antibodies for 1 hours at room temperature. Membranes were developed using ECL sol. (Clarity Western ECL Substrate, 500 ml #1705061) detected 30 sec by LAS-500 (GE Healthcare,USA). The density of each band was quantified using the ImageJ software. Each experiment was performed in triplicate to obtain the average.

2.6. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Graph pad prism (version 10). The comparison of the differences between groups was conducted by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and then multiple comparison test used Duncan’s test. The difference between the control values and the other values was considered to be significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the PSNPs 50 nm

The PSNP 50 nm (HCT-CRM-P0050) were packaged in 1 % (g/L, ppm) aqueous suspension at a concentration. These beads The certified mean diameter of the particles is within ± (3–5) % of the nominal diameter. The standard deviation of the particle size dis-tribution ranges from (0.5–5) % of the nominal diameter by TSI / SMPS(Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer) (

Supplementary Materials Figure S1). The density of the material is measured at 1.00 g/L. The index of refraction falls between 1.57 and 1.61 by Anton Paar / ABBEMAT 550 (

Supplementary Materials Figure S2). The approximate concentration of the solution is 1 %. The pH value of the solution ranges from 3 to 7(by TOADKK / HM-40X) (

Table 1).

3.2. Viability of the RBE4 Cells with Treatment PSNP

The viability of the RBE4 cells was examined to determine the potential cytotoxicity of the PSNP 50 nm. It was not found that PS-NPs could cause RBE4 cell death in a manner depend-ent on the maximum 500 ug/ml dose. The viability of the RBE4 cells was examined to determine the potential cytotoxicity of the PSNP 50 nm. It was not found that PSNPs could cause RBE4 cell death in a manner dependent on the maximum 500 ug/ml dose(

Figure 2B). The general population is not exposed to high doses greater than 200 ppb of PSNP per day [

15]. Therefore, 24 h of treatment with 100 and, 200 μg/mL PSNPs was selected for use.

3.3. Viability of the Z310 cells with Treatment PSNP

The viability of the Z310 cells was examined to determine the potential cytotoxicity of the PSNPs 50nm. It was found that PSNPs could cause Z310 cell death in a manner dependent on the dose. Notably, the viability of Z310 cells significantly decreased following 24 h of 500 μg/mL PSNPs treatment(

Figure 3B). Therefore, 24 h of treatment with 100 and 200 μg/mL PSNPs was selected for use.

3.4. Effects of Membrane Transport Protein Expression of RBE4 Cells with PSNP

Western blot analysis revealed that treatment with PSNPs 50 nm was not change LRP1, P-gp, and RAGE (

Figure 2C–G) of RBE4 cells. Although a concentration-dependent increase in P-gp was observed, the difference was not statistically significant.

3.5. Effects of Membrane Transport Protein Expression of Z310 Cells with PSNP

Western blot analysis further revealed that treatment with PSNPs 50 nm upregulated P-gp protein to concentration-dependent increased statistically significant. but other proteins were not changed (

Figure 3C–G). The findings above suggest that PSNP 50 nm can imbalance P-gp protein in Z310 cells.

4. Discussion

A recent academic paper estimates that nearly 80 percent of the 8 billion metric tons of plastic ever produced have ended up in landfills or the environment [

16]. In addition, microplastics and nanoplastics are becoming a major issue as they act as sources of exposure in drinking water and food. In a study, tap water was filtered sequentially from 0.45 μm filter pore size to 200, 100, and 20 nm to screen for nanoplastics, and the main particle sizes were 255 nm, 148 nm, and 58 nm [

17]. Recent review paper suggested that the unique toxicity mechanisms of microplastics and nanoplastics (MPs/NPs) need to be studied in terms of (bio-accumulation) and pathway activation due to the differences in physical properties of Micro and Nano, and compared the toxicity risks of microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs) on digestive, reproductive, and nervous systems. In summary, it was reported that nanoplastics can cause higher reproductive toxicity and neurotoxicity than microplastics in terms of reproductive and neurotoxicity. This study systematically analyzed the differences in toxicity between MPs and NPs and suggested future research directions [

18]. Microplastics and nanoplastics have various components and shapes of plastic particles, and the reason why spherical Polystyrene Nanoplastics were chosen is that polystyrene is one of the most commonly used plastics in toothbrushes, toys, CDs, Styrofoam, etc., and can be broken down to nano-size, accumulated in organisms, and transmitted through the food chain. And we confirmed the neurotoxic effects on hippocampal neurogenesis by exposing neural progenitor cells and mice (C57BL) to particles of Polystyrene Nanoplastics (30, 50, and 2000 nm)[

19]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that microplastics and nanoplastics can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), affect protein folding at the molecular level in particular, and induce the formation of abnormal amyloid proteins, potentially leading to the development of systemic and local amyloidosis [

20].

In animal experiments where polystyrene nanoplastic particles were orally administered to 30-50 nm, PSNP particles were reported to pass through the BBB and accumulate in the brain, and a study was conducted using three types of cells derived from the brain of mice to confirm the effects of PSNP on cell function. As a result, MEFs cells and astrocytes cells were exposed to 100 nm PSNP at 0, 50, 100, and 200 ppm, suggesting that this could have a negative effect on neurogenesis and cognitive function. Our study also referred to this paper and explained the target concentration as control, 100, and 200 ppm, and the particle size was determined to be 50 nm [

21].

The RBE4 cells used in the experiment are the main cells that make up the BBB derived from rats, and the Z310 cells are the main cells that make up the BCB derived from rats. The polystyrene nanoplastic (50 nm) used in the experiment is a material manufactured by a domestic (Republic of Korea) company and is a certified standard material with an ISO 17034 certificate. It was manufactured according to ISO Guide 35 and is officially registered with COMAR, the International Standard Material Registration Center.

LRP1 (Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1) Lipoprotein Metabolism: LRP1 plays a crucial role in the metabolism of lipoproteins and helps remove lipids from the bloodstream. Endocytosis: It is involved in the endocytosis process, internalizing various molecules, including proteins and lipids. Cell Growth and Migration: LRP1 regulates cell growth, migration, and differentiation, which are essential for tissue development and repair. Inflammation and Apoptosis: It modulates inflammatory responses and apoptosis (programmed cell death), contributing to immune system function and cellular homeostasis. Blood-Brain Barrier: LRP1 maintains the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, protecting the brain from harmful substances. Disease Associations: LRP1 is associated with several diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, due to its roles in cellular processes and signaling pathways. Due to these diverse functions, LRP1 is considered an important protein in both normal physiology and disease states.

P-glycoprotein Metabolism: Biological Barrier: P-glycoprotein acts as a biological barrier by expelling toxins and foreign substances from cells, protecting tissues from potentially harmful compounds. Drug Absorption and Disposition: P-glycoprotein affects the pharmacokinetics of many drugs, influencing their absorption, distribution, and elimination. This can impact how well drugs are absorbed in the intestines, distributed throughout the body, and how quickly they are excreted. Blood-Brain Barrier: In the BBB, P-glycoprotein prevents neurotoxic substances from entering the brain, maintaining a protective environment by actively expelling these substances. Multidrug Resistance: In cancer treatment, P-glycoprotein plays a key role in multidrug resistance (MDR). It expels anticancer drugs from cancer cells, reducing their effectiveness and posing challenges for chemotherapy. Due to these roles, P-glycoprotein is a crucial factor in protecting the body from harmful substances and influencing the efficacy of various drugs.

RAGE (Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts)

Inflammation: RAGE plays a significant role in mediating inflammatory responses. It binds to advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) and other ligands, activating inflammatory signaling pathways. Cellular Stress Response: RAGE expression increases in response to cellular stress, regulating cell metabolism and survival. It enhances autophagy and reduces apoptosis, helping cells adapt to stress. Disease Associations: RAGE is associated with several diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer. For example, in Alzheimer’s disease, RAGE is involved in transporting amyloid-beta across the blood-brain barrier. Tissue Remodeling and Repair: RAGE regulates tissue remodeling and repair processes by interacting with various ligands, influencing matrix remodeling and cell migration. Immune Response: RAGE is involved in innate immune responses, contributing to immune cell activation and cytokine production. Due to these diverse functions, RAGE is considered an important protein in normal physiological processes and the development of various diseases. [

7]

The function of P-gp in the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is to protect the brain from the accumulation of toxic substances and maintain the homeostasis of the central nervous system (CNS).

The location of P-gp in the blood-brain barrier (BCB) is on the blood side and the CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) side, and it is not yet clear which side is more abundant.

Additional amylodextrin transport experiments are needed to confirm whether the results of this experiment on the increase in P-gp in Z310 cells(BCB) are due to the increase in P-gp caused by the influx of nanoplastics into the brain parenchyma or the increase in P-gp caused by the increase in Amyloid beta caused by nanoplastics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Byung-Sun Choi. and Young-Hun Kim.; methodology, Byung-Sun Choi. and Young-Hun Kim.; software, Young-Hun Kim.; validation, Byung-Sun Choi, Young-Hun Kim and Yulli Kim.; formal analysis, Eunhee Kim and Byungho moon.; investigation, Young-Hun Kim.; resources, Byung-Sun Choi.; data curation, Byung-Sun Choi.; writing—original draft preparation, Young-Hun Kim.; writing—review and editing, Byung-Sun Choi.; visualization, Young-Hun Kim.; supervision, Byung-Sun Choi.; project administration, Young-Hun Kim.; funding acquisition, Eunhee Kim and Byungho moon.

Funding

We supported as a trainee of the environmental health training program which was provided by the Environmental Health Centre of the Catholic University of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea (2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We supported the PSNP standard material from HCT Company and used it in our study. We also received the analysis results from the company.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kik, Kinga, Bożena Bukowska, and Paulina Sicińska. “Polystyrene nanoparticles: Sources, occurrence in the environment, distribution in tissues, accumulation and toxicity to various organisms.” Environmental Pollution 262 (2020): (p. 114297).

- Vethaak, A. Dick, and Juliette Legler. “Microplastics and human health.” Science 371.6530 (2021): (p. 672-674).

- Nguyen, Brian, et al. “Separation and analysis of microplastics and nanoplastics in complex environmental samples.” Accounts of chemical research 52.4 (2019): (p. 858-866).

- Jabbar, Abdullah Hasan, et al. “Green Synthesis of Silver/Polystyrene Nano Composite (Ag/PS NCs) via Plant Extracts Beginning a New Era in Drug Delivery.” Indian J. Sci. Technol 11.22 (2018): (p. 1-9).

- Rahman, Md Ataur, et al. “Exposure to environmental arsenic and emerging risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: Perspective mechanisms, management strategy, and future directions.” Toxics 9.8 (2021): (p. 188).

- Li, Chao, et al. “Inhibiting ferroptosis in brain microvascular endothelial cells: A potential strategy to mitigate polystyrene Nanoplastics‒Induced blood‒Brain barrier dysfunction.” Environmental Research (2024): (p. 118506).

- Jedlitschky, G., S. Vogelgesang, and H. K. Kroemer. “MDR1–P-glycoprotein (ABCB1)-Mediated Disposition of Amyloid-β Peptides: Implications for the Pathogenesis and Therapy of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 88.4 (2010): 441-443.

- Chai, Amanda B., et al. “P-glycoprotein: a role in the export of amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease?.” The FEBS journal 287.4 (2020): (p. 612-625).

- Ucar, A.; Parlak, V.; Ozgeris, F. B.; Yeltekin, A. C.; Arslan, M. E.; Alak, G.; Turkez, H.; Kocaman, E. M.; Atamanalp, M. Magnetic nanoparticles-induced neurotoxicity and oxidative stress in brain of rainbow trout: Mitigation by ulexite through modulation of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic activities. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, (p. 838), No. 155718.

- Tan, M. S.; Yu, J. T.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, X. C.; Tan, L. The NLRP3 inflammasome in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 48, (p. 875− 882). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Solt, A. C.; Henriquez-Roldan, C.; Torres-Jardon, R.; Nuse, B.; Herritt, L.; Villarreal-Calderon, R.; Osnaya, N.; Stone, I.; Garcia, R.; Brooks, D. M.; Gonzalez-Maciel, A.; Reynoso-Robles, R.; Delgado-Chavez, R.; Reed, W. Long-term air pollution exposure is associated with neuroinflammation, an altered innate immune response, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, ultrafine particulate deposition, and accumulation of amyloid beta-42 and alpha-synuclein in children and young adults. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008, 36, (p. 289−310).

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Azzarelli, B.; Acuna, H.; Garcia, R.; Gambling, T. M.; Osnaya, N.; Monroy, S.; Del Rosario Tizapantzi, M.; Carson, J. L.; Villarreal-Calderon, A.; Rewcastle, B. Air pollution and brain damage. Toxicol. Pathol. 2002, 30, (p. 373−389)

. [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Maronpot, R. R.; Torres-Jardon, R.; Henriquez-Roldan, C.; Schoonhoven, R.; Acuna-Ayala, H.; VillarrealCalderon, A.; Nakamura, J.; Fernando, R.; Reed, W.; Azzarelli, B.; Swenberg, J. A. DNA damage in nasal and brain tissues of canines exposed to air pollutants is associated with evidence of chronic brain inflammation and neurodegeneration. Toxicol. Pathol. 2003, 31, (p. 524− 538). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Genghuan, Yingcong Lin, and Heping Shen. “Exposure to polystyrene microplastics promotes the progression of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: association with induction of microglial pyroptosis.” Molecular Neurobiology 61.2 (2024): (p. 900-907).

- Xu, Jun-Li, et al. “A review of potential human health impacts of micro-and nanoplastics exposure.” Science of the Total Environment 851 (2022): (p. 158111).

- Ivleva, Natalia P. “Chemical analysis of microplastics and nanoplastics: challenges, advanced methods, and perspectives.” Chemical reviews 121.19 (2021): (p.11886-11936).

- Li, Yu, Zeqian Wang, and Baohong Guan. “Separation and identification of nanoplastics in tap water.” Environmental Research 204 (2022): (p. 112134).

- Yin, Kai, et al. “A comparative review of microplastics and nanoplastics: Toxicity hazards on digestive, reproductive and nervous system.” Science of the total environment 774 (2021): (p. 145758).

- Yang, Seonguk, et al. “Cationic nanoplastic causes mitochondrial dysfunction in neural progenitor cells and impairs hippocampal neurogenesis.” Free Radical Biology and Medicine 208 (2023): (p. 194-210).

- Windheim, Joseph, et al. “Micro-and nanoplastics’ effects on protein folding and amyloidosis.” International journal of molecular sciences 23.18 (2022): (p.10329).

- Paing, Yunn Me Me, et al. “Neurotoxic effects of polystyrene nanoplastics on memory and microglial activation: Insights from in vivo and in vitro studies.” Science of the Total Environment924 (2024): (p. 171681).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).