Submitted:

27 September 2024

Posted:

29 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. CMFs and BBB-NET Preparation

2.4. Astrocyte (HASTR/ci35) Labelling

2.5. Blocking the CMF–Integrin Interaction in Astrocytes

2.6. Immunostaining

2.7. Analysis of Protein Expression in the 3D BBB Models

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Collagen I Microfibers in BBB-NET Hydrogel Enhanced Autonomous Brain Capillary Network Formation

3.2. CMFs Supported Astrocyte (HASTRs/ci35) Survival

3.3. Astrocytes Promote the Formation and Maturation of Capillary Networks

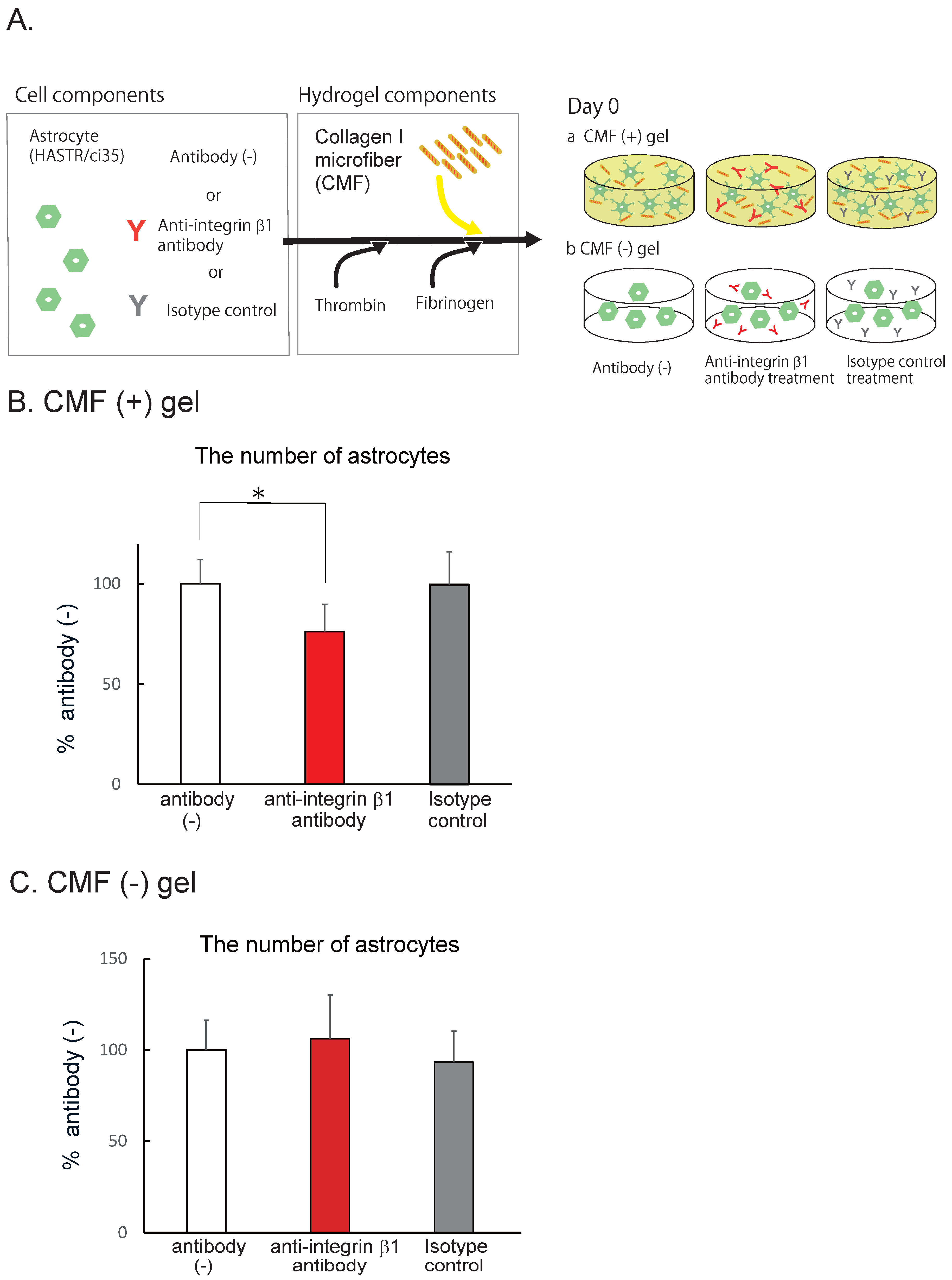

3.4. CMFs Enhanced Astrocyte (HASTR/ci35) Survival by Interacting with Integrin b1

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| BBB | blood-brain barrier; |

| MPS | microphysiological system; |

| CNS | central nervous system; |

| PKPD | pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics; |

| TKTD | toxicokinetics/toxicodynamics; |

| CoU | context of use; |

| TfR | transferrin receptor; |

| CMF | collagen microfiber; |

| QC | quality control; |

| EC | endothelial cell; |

| AC | astrocyte; |

| PC | pericyte; |

| BM | basement membrane; |

| ECM | extracellular matrix; |

| SOP | standard operating procedure |

References

- Pardridge, W.M. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, D.; Xu, C.; Sun, P.; Wu, J.; Yan, C.; Hu, M.; Yan, N. Crystal structure of the human glucose transporter GLUT1. Nature. 2014, 510, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, M.S.; Krizanac-Bengez, L.; Macchia, F.; Naftalin, R.J.; Pedley, K.C.; Mayberg, M.R.; Marroni, M.; Leaman, S.; A Stanness, K.; Janigro, D. Mechanisms of glucose transport at the blood-brain barrier: an in vitro study. Brain Res. 2001, 904, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.; Kim, H. Characterization of a microfluidic in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (μBBB). Lab. Chip. 2012, 12, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicker, J.; Alves, G.; Fortuna, A.; Falcão, A. Blood-brain barrier models and their relevance for a successful development of CNS drug delivery systems: a review. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 87, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. Consideration for future in vitro BBB models - technical development to investigate the drug delivery to the CNS. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2018, 152, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, Y.; Ohtsuki, S.; Katsukura, Y.; Ikeda, C.; Suzuki, T.; Kamiie, J.; Terasaki, T. Quantitative targeted absolute proteomics of human blood-brain barrier transporters and receptors. J. Neurochem. 2011, 117, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, M.S.; Zerangue, N.; Woodford, K.; Roberts, L.M.; Tate, E.H.; Feng, B.; Li, C.; Feuerstein, T.J.; Gibbs, J.; Smith, B.; et al. Comparative gene expression profiles of ABC transporters in brain microvessel endothelial cells and brain in five species including human. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 59, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potjewyd, G.; Kellett, K.A.B.; Hooper, N.M. 3D hydrogel models of the neurovascular unit to investigate blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Neuronal Signal 2021, 5, Ns20210027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, A.; Sivandzade, F.; Archie, S.R.; Chowdhury, E.A.; Noorani, B.; Cucullo, L. In vitro modeling of the neurovascular unit: advances in the field. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Hui, H.; Cai, T.; Huang, H.; Yang, F.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X. CD146 coordinates brain endothelial cell-pericyte communication for blood-brain barrier development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2017, 114, E7622–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agathe, F.; Yasuhiro, N.; Yukari, S.M.; Tomomi, F.; Kaoru, S.; Matsusaki, M. An in vitro self-organized three-dimensional model of the blood-brain barrier microvasculature. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 16, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piantino, M.; Kang, D.H.; Furihata, T.; Nakatani, N.; Kitamura, K.; Shigemoto-Mogami, Y.; Sato, K.; Matsusaki, M. Development of a three-dimensional blood-brain barrier network with opening capillary structures for drug transport screening assays. Mater. Today Bio. 2022, 15, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.R.; Ceccarelli, J.; Vigen, M.L.; Gudur, M.; Singh, R.; Deng, C.X.; Putnam, A.J.; Stegemann, J.P. Effects of hydroxyapatite on endothelial network formation in collagen/fibrin composite hydrogels in vitro and in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 3091–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.R.; Peterson, A.W.; Ceccarelli, J.; Putnam, A.J.; Stegemann, J.P. Matrix composition regulates three-dimensional network formation by endothelial cells and mesenchymal stem cells in collagen/fibrin materials. Angiogenesis 2012, 15, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedhassantehrani, N.; Li, Y.; Yao, L. Dynamic behaviors of astrocytes in chemically modified fibrin and collagen hydrogels. Integr. Biol. (Camb). 2016, 8, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critser, P.J.; Kreger, S.T.; Voytik-Harbin, S.L.; Yoder, M.C. Collagen matrix physical properties modulate endothelial colony forming cell-derived vessels in vivo. Microvasc. Res. 2010, 80, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Piantino, M.; Zeng, J.; Louis, F.; Xie, Z.; Furihata, T.; Matsusaki, M. Control of blood capillary networks and holes in blood-brain barrier models by regulating elastic modulus of scaffolds. Mater. Today Bio. 2023, 21, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornev, V.A.; Grebenik, E.A.; Solovieva, A.B.; Dmitriev, R.I.; Timashev, P.S. Hydrogel-assisted neuroregeneration approaches towards brain injury therapy: A state-of-the-art review. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wevers, N.R.; Kasi, D.G.; Gray, T.; Wilschut, K.J.; Smith, B.; van Vught, R.; Shimizu, F.; Sano, Y.; Kanda, T.; Marsh, G.; et al. A perfused human blood-brain barrier on-a-chip for high-throughput assessment of barrier function and antibody transport. Fluids Barriers CNS 2018, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiichi, A.; Furihata, T.; Kishida, S.; Ohta, Y.; Saito, K.; Kawamatsu, S.; Chiba, K. Establishment of a new conditionally immortalized cell line from human brain microvascular endothelial cells: a promising tool for human blood-brain barrier studies. Brain Res. 2012, 1488, 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furihata, T.; Kawamatsu, S.; Ito, R.; Saito, K.; Suzuki, S.; Kishida, S.; Saito, Y.; Kamiichi, A.; Chiba, K. Hydrocortisone enhances the barrier properties of HBMEC/ciβ, a brain microvascular endothelial cell line, through mesenchymal-to-endothelial transition-like effects. Fluids Barriers CNS 2015, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umehara, K.; Sun, Y.; Hiura, S.; Hamada, K.; Itoh, M.; Kitamura, K.; Oshima, M.; Iwama, A.; Saito, K.; Anzai, N.; et al. A New Conditionally Immortalized Human Fetal Brain Pericyte Cell Line: Establishment and Functional Characterization as a Promising Tool for Human Brain Pericyte Studies. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 5993–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furihata, T.; Ito, R.; Kamiichi, A.; Saito, K.; Chiba, K. Establishment and characterization of a new conditionally immortalized human astrocyte cell line. J. Neurochem. 2016, 136, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, R.; Umehara, K.; Suzuki, S.; Kitamura, K.; Nunoya, K.I.; Yamaura, Y.; Imawaka, H.; Izumi, S.; Wakayama, N.; Komori, T.; et al. A Human Immortalized Cell-Based Blood-brain Barrier Triculture Model: Development and Characterization as a Promising Tool for Drug-Brain Permeability Studies. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 4461–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, Y.; Kitano, S.; Irie, S.; Matsusaki, M. Wholly vascularized millimeter-sized engineered tissues by cell-sized microscaffolds. Mater. Today Bio. 2020, 6, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamoto, T.; Hikida, M.; Sato, S.; Oyama, S.; Tachi, Y.; Kuroda, S.; Mazuka, T.; Ebina, K.; Nakai, T.; Nakata, K. Integrin α2β1 plays an important role in the interaction between human articular cartilage-derived chondrocytes and atelocollagen gel. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Bihan, D.; Chang, F.; Huang, P.H.; Farndale, R.W.; Leitinger, B. Discoidin domain receptors promote α1β1- and α2β1-integrin mediated cell adhesion to collagen by enhancing integrin activation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Duan, H.; Feng, J.; Xiang, J.; Feng, L.; Liu, D.; Chen, X.; Jing, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, D.; et al. Soluble CD146, a cerebrospinal fluid marker for neuroinflammation, promotes blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Theranostics 2020, 10, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemoto-Mogami, Y.; Nakayama-Kitamura, K.; Sato, K. The arrangements of the microvasculature and surrounding glial cells are linked to blood-brain barrier formation in the cerebral cortex. Front. Neuroanat. 2024, 18, 1438190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, D. Three-dimensional remodeling of functional cerebrovascular architecture and gliovascular unit in leptin receptor-deficient mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2021, 41, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Hui, H.; Cai, T.; Huang, H.; Yang, F.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X. CD146 coordinates brain endothelial cell-pericyte communication for blood-brain barrier development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E7622–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, M.S.; Routhe, L.J.; Moos, T. The vascular basement membrane in the healthy and pathological brain. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 3300–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elango, J.; Hou, C.; Bao, B.; Wang, S.; Maté Sánchez de Val, J.E.; Wenhui, W. The Molecular Interaction of Collagen with Cell Receptors for Biological Function. Polymers 2022, 14, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilella, E.; Gas, C.; Garcia-Ruiz, B.; Rivera, F.J. Expression of DDR1 in the CNS and in myelinating oligodendrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 118483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; He, X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xie, R.; Liu, Z.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, N.; Xiang, Q.; Cui, Y. Targeting integrin pathways: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soles, A.; Selimovic, A.; Sbrocco, K.; Ghannoum, F.; Hamel, K.; Moncada, E.L.; Gilliat, S.; Cvetanovic, M. Extracellular Matrix Regulation in Physiology and in Brain Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauren, K.; Wareham, Robert O. Lauren K. Wareham, Robert O. Baratta, Brian J. Del Buono, Eric Schlumpf & David J. Calkins. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Twardowski, T.; Fertala, A.; Orgel, J.P.; San Antonio, J.D. Type I collagen and collagen mimetics as angiogenesis promoting superpolymers. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 3608–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Kitano, S.; Irie, S.; Levato, R.; Matsusaki, M. Collagen Microfibers Induce Blood Capillary Orientation and Open Vascular Lumen. Adv. Biosyst. 2020, 4, e2000038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezu-Ndubuisi, O.J.; Maheshwari, A. The role of integrins in inflammation and angiogenesis. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcor, J.D.; Mallein-Gerin, F. Biomaterial functionalization with triple-helical peptides for tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2022, 148, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, Y.; Kitazato, K.; Basaki, Y. Integrin-linked kinase regulates vascular morphogenesis induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117 Pt 3, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, L.; Venturino, M.; Bozzo, C.; Silengo, L.; Altruda, F.; Beguinot, L.; Tarone, G.; Defilippi, P. Integrins induce activation of EGF receptor: role in MAP kinase induction and adhesion-dependent cell survival. Embo J. 1998, 17, 6622–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabata, H.; Sasaki, M.; Agetsuma, M.; Sano, H.; Hirota, Y.; Miyajima, M.; Hayashi, K.; Honda, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Inaguma, Y.; et al. Erratic and blood vessel-guided migration of astrocyte progenitors in the cerebral cortex. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y. Discoidin domain receptors: Microenvironment sensors that promote cellular migration and invasion. Cell Adh. Migr. 2018, 12, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).