1. Introduction

The concept of proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) represents contemporary and innovative therapeutic modalities, first established by Crews and colleagues in 2001 [

1]. PROTACs’ catalytic mode of action (MOA) potentially offers several advantages over small molecule inhibitors (SMIs), such as the accessibility of previously undruggable targets, enhanced protein isoform selectivity, or reduced dosing frequency [

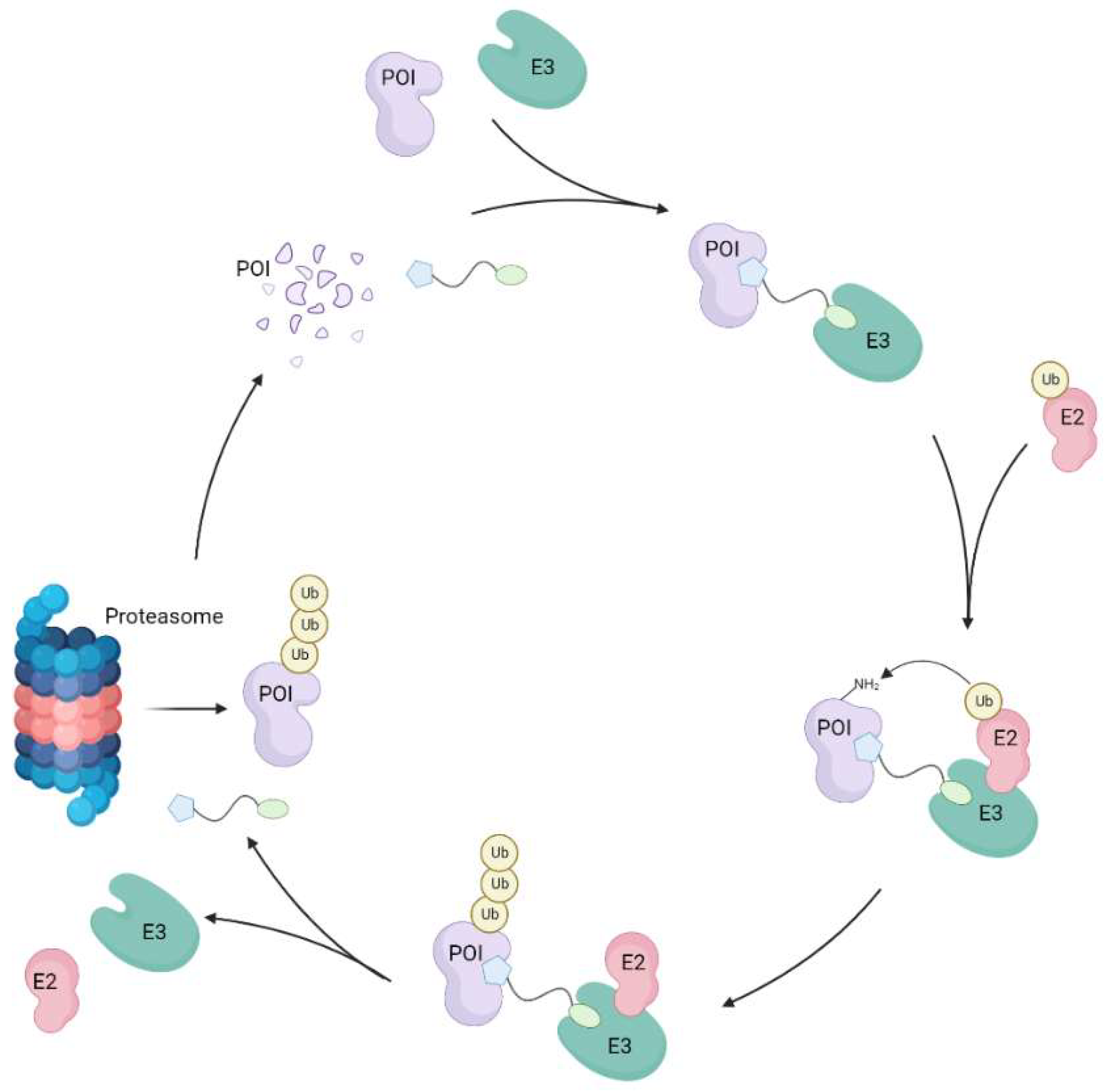

2]. PROTACs induce the degradation of a protein of interest (POI) by hijacking the intrinsic cellular ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), thereby triggering a conditional POI-knockdown phenotype [

1,

3]. The UPS itself is an essential pathway in cells that physiologically regulates the life cycle of proteins. Hence, while regulating the degradation of damaged or misfolded proteins in general, it plays major roles, e.g., in the regulation of the cell cycle, as well as inflammatory and immune responses [

4,

5,

6]. Dysregulation of the UPS is often associated with diseases, including different forms of cancer as well as neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, or Huntington’s disease [

7,

8,

9]. Compared to SMIs, the alternative MOA of PROTACs correlates to their nature as heterobifunctional molecules. Typical PROTAC compounds, e.g., consist of both an E3 ligase ligand and a POI ligand, which are connected via different types of linkers [

10]. These chimeric molecules are therefore able to simultaneously recruit the respective E3 ligase and the POI, forming ternary complexes. Consecutively, due to the induced spatial proximity, the E3 ligase is able to bind an E2 ligase that transfers ubiquitin moieties to lysine residues on the POI surface, thereby labelling that protein for cellular waste disposal [

11,

12]. Consequently, lysine polyubiquitination is then recognized by the 26S proteasome, and the targeted POI is degraded, while the PROTAC itself is released and able to form another ternary complex (

Figure 1) [

13,

14]. In this regard, PROTACs are able to go through multiple cycles of complexing with POI and E3 ligase, facilitating catalytic degradation of the POI in sub-stoichiometric amounts [

15].

When designing and developing novel, effective PROTAC compounds, picking the right linker motif plays a major role (“linkerology”). Since both the POI- and E3 ligase-addressing ligands are mostly set in their physicochemical properties, variation in the used linker is often key to influencing PROTAC features, such as biological activity, physicochemical parameters coding for solubility, cellular permeability, and metabolic stability [

16,

17,

18]. Of note, empirically finding the right linker length is often key, and the absence or presence of a single atom within the linker moiety can differentiate whether a PROTAC is bioactive or not. In line with this notion, linkers too short may not allow each ligand to interact with their respective protein due to steric hindrance, which makes it impossible to form the required ternary complexes. As a result, respective compounds do not lead to polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation. If the linker is too long, ternary complexes may be formed, although POI-degradation may still not occur due to the formation of “non-ideal” proximity between POI and E3 ligase being insufficient to result in ubiquitination [

14,

19].

1.1. CK1 isoforms as proteins of interest for PROTAC design

The highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed CK1 family of serine/threonine kinases consists of 7 members (α, β, γ1, γ2, γ3, δ, and ε). CK1 isoforms and various splice variants in humans are known to be linked to several regulatory roles such as DNA processing and repair, proliferation, apoptosis, cell differentiation, and circadian rhythm [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. One of the most researched and best-characterised CK1-regulated mechanisms to date is the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which mainly controls cell proliferation. If Wnt receptors are stimulated through binding of respective Wnt ligands, β-catenin is translocated to the nucleus, which ultimately leads to transcription and expression of Wnt-dependent target genes. However, if Wnt ligands are absent, a “destruction complex” consisting of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), AXIN, CK1α, and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is formed in the cytoplasm to capture β-catenin and induce its degradation through phosphorylation of CK1α and GSK3 [

23,

25,

26]. Additionally, CK1δ/ε control Wnt signalling via phosphorylation of Dishevelled (DVL1/2/3) proteins [

27]. Dysregulation of the CK1δ isoform is known to be linked to various forms of diseases, e.g., cancer (i.e., colon, pancreatic, breast, and ovarian cancer), as well as neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases, rendering this isoform a highly attractive target for medicinal chemistry-based approaches [

28,

29,

30].

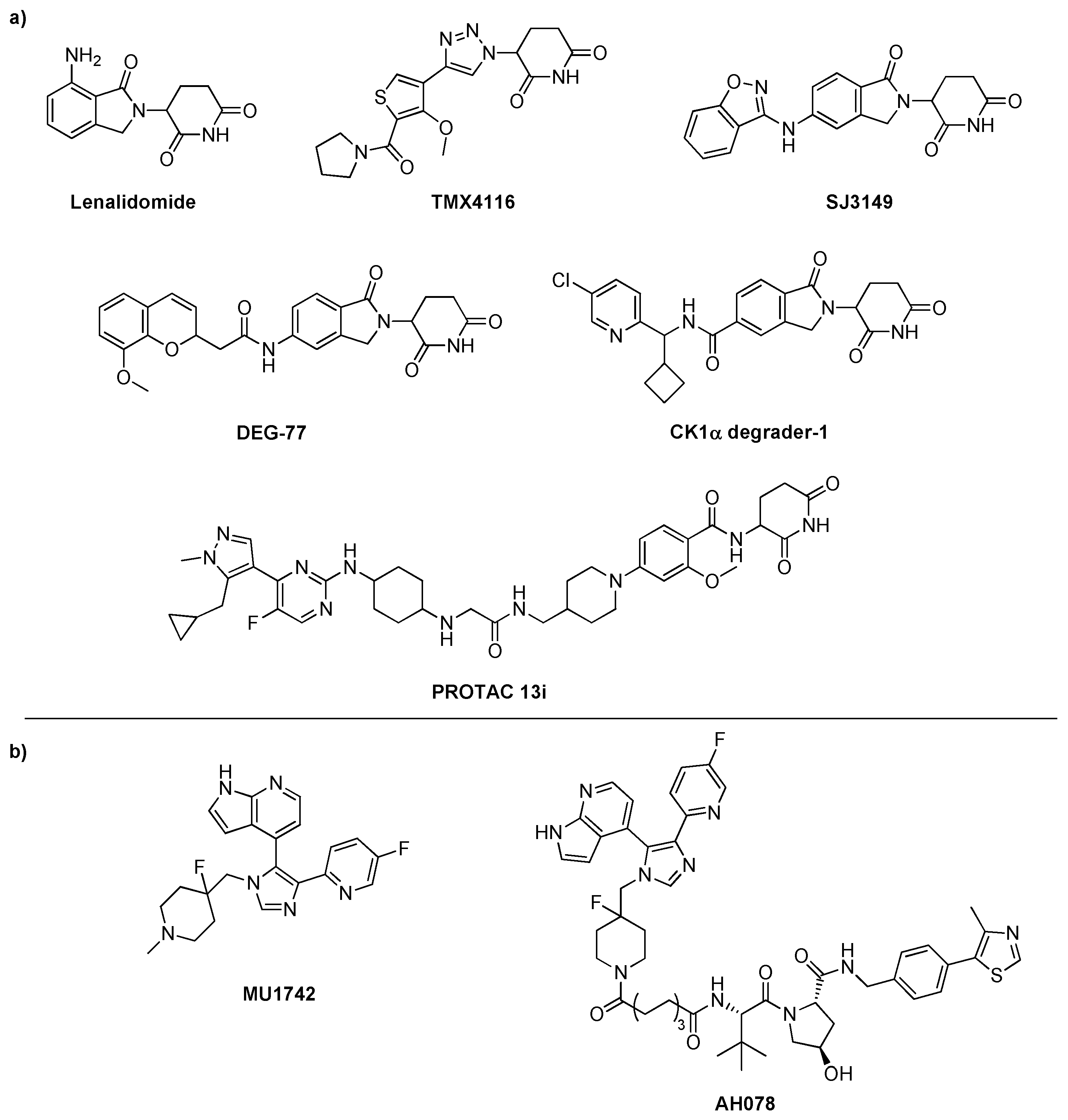

When it comes to CK1 targeted protein degradation (TPD), so far, compounds targeting CK1α have been reported, including CK1 molecular glue degraders like lenalidomide, TMX4116, SJ7095/SJ3149, DEG-77 [

31], CK1α degrader-1 [

32], and PROTAC 13i [

33] (

Scheme 1). While our work was in progress, in December 2024, Haag et al. reported their degrader compounds targeting CK1δ and CK1ε. They demonstrated that although compound AH078 showed a reported DC

50 value of 0.55 μM and D

max of 70 % towards CK1δ, all compounds lacked isoform selectivity regarding CK1δ/ε, likely due to the high homology between their respective kinase ATP-binding domains [

23,

28,

34].

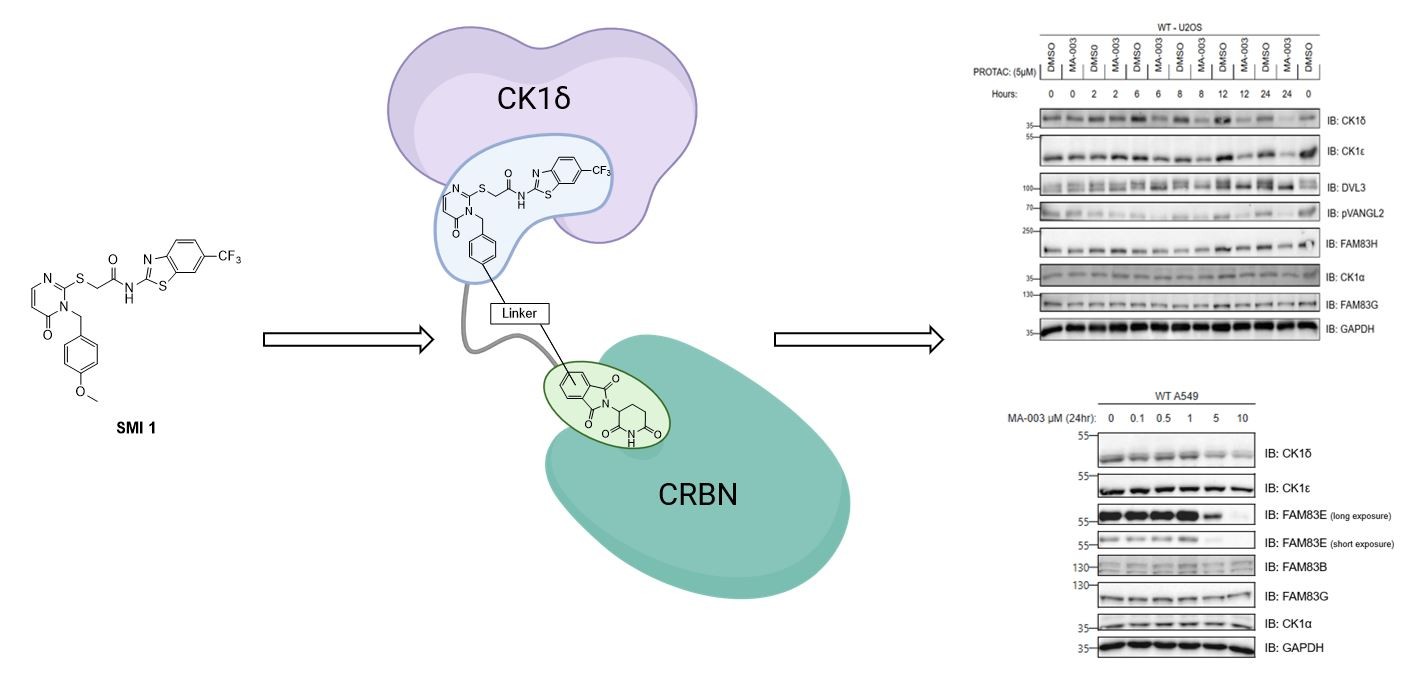

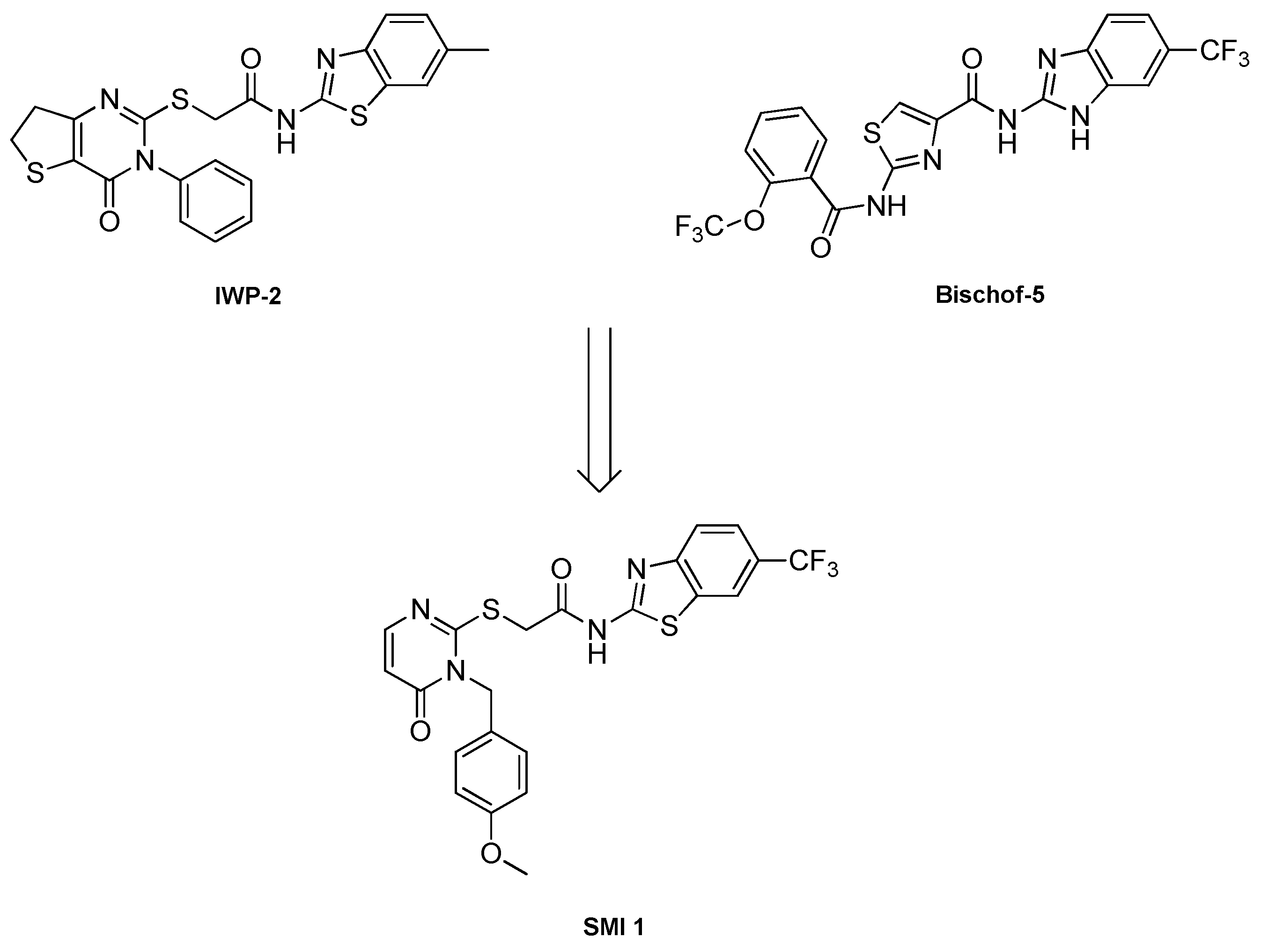

Motivated especially by the lack of CK1δ-specific degraders at the inception of our project, we started a synthetic project towards the development of a platform containing various types of linker motifs of different lengths and variable types of E3 ligase ligands. In contrast to the “tear drop” type of CK1δ inhibitor used by Haag et al [

34] in their recently reported CK1 PROTACs, we set out to employ a “linear” CK1δ inhibitor moiety in our project, since former efforts towards “linear” CK1δ/ε-specific inhibitors in our group led to the discovery of

SMI 1 (

Scheme 2) [

35,

36]. The CK1δ-specific inhibitor is based on the scaffold of established IWP compounds (i.e.,

IWP-2) [

37,

38] and known CK1-specific benzimidazole-based inhibitors such as

Bischof-5 [

39]

. Such degrader probes would be highly useful to further study CK1 isoform-dependent processes, e.g., in cancer cells. Based on strong SAR data and having structural data of a ligand-protein complex for

SMI 1 in hand, we first aimed to identify a suitable linker-attachment position at the CK1δ-specific inhibitor scaffold.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we established a flexible synthetic platform for the modular preparation of designed CK1δ-PROTACs following the ternary scheme CK1δ-ligand - linker - E3 ligase ligand. We applied this platform to generate two different sets of projected PROTAC degrader compounds towards CK1δ. The synthetic route previously published by our group in 2019 was applied and extended to generate an inhibitor compound (I9) containing an aniline moiety, facilitating linker attachment via amide coupling. All dimeric intermediate compounds (L6a-d, L8a-d) were generated in sufficient quantities to be employed in the final amide coupling in order to generate the PROTAC compounds.

While alkyl-linker PROTAC compounds P1a-d (three through six methylene groups respectively) were synthesized successfully with yields in the range from 6 to 22 %, compounds P2b and P2c (four and five methylene groups) of this series could not be generated by the method. Despite our efforts towards expanded variations regarding solvent, reaction time, temperature, and coupling reagents, all attempts were ineffective in yielding the desired compounds P2b and P2c.

The set of PROTACs containing PEG linker motifs, however, were synthesized successfully, possibly due to their length and higher conformational flexibility compared to alkyl linkers. Overall, we were successful in establishing a versatile and effective synthetic platform for the systematic synthesis of various PROTAC candidate compounds.

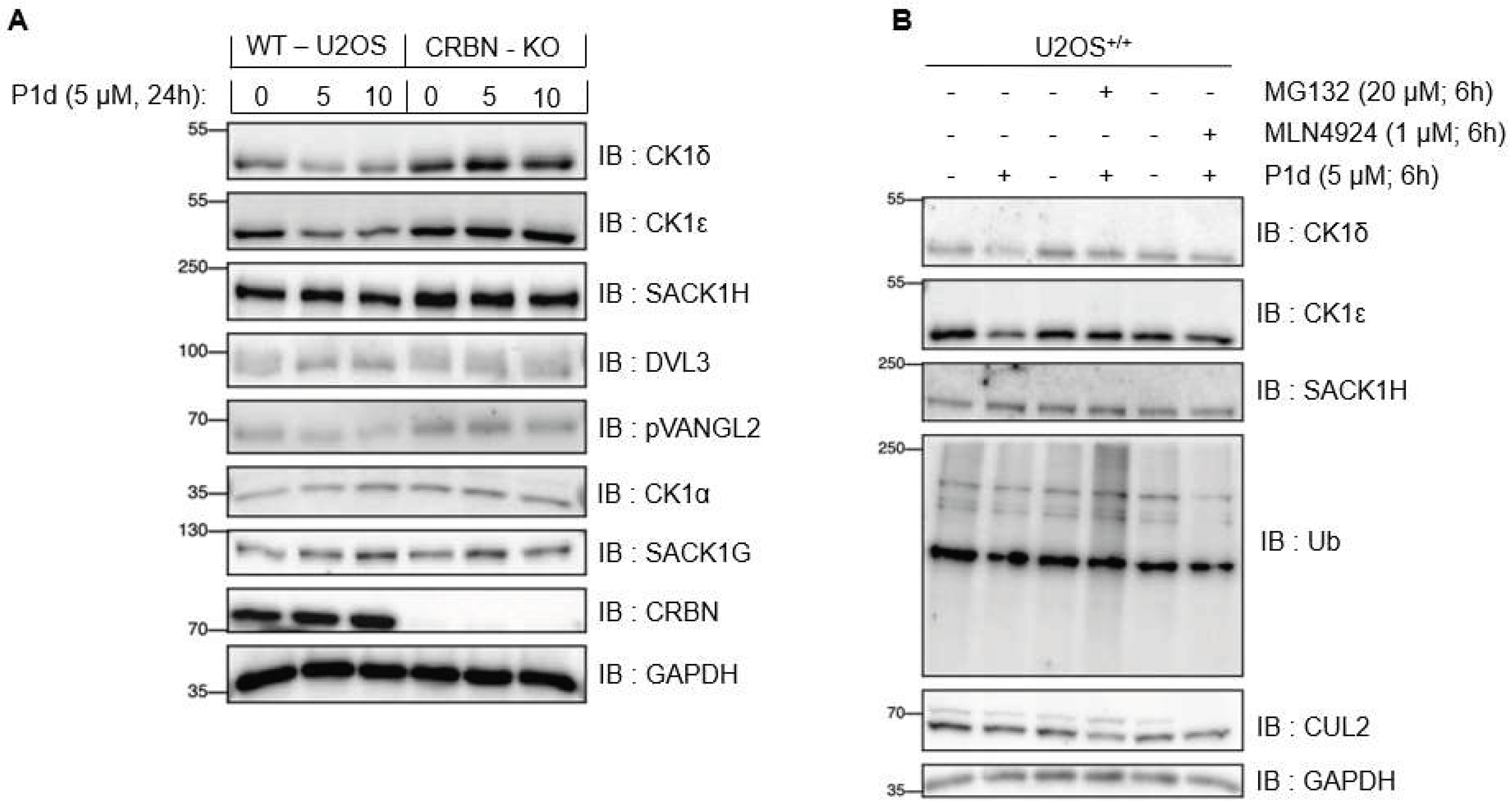

We were able to apply all our PROTAC candidate molecules in various cells to assess the potential degradation of CK1 isoforms, their interacting partners, and assess the impact on phosphorylation of downstream substrates. A few PROTACs induced a dose-dependent degradation of CK1δ and CK1ε but not the related kinase CK1α. P1d was the most potent CK1δ/ε degrader, robustly degrading these kinases at concentrations of 5 μM and 10 μM within 6 h in multiple cell lines, including U2OS and A549. We established that P1d degrades CK1δ/ε via the CUL4CRBN E3 ligase complex and the proteasome.

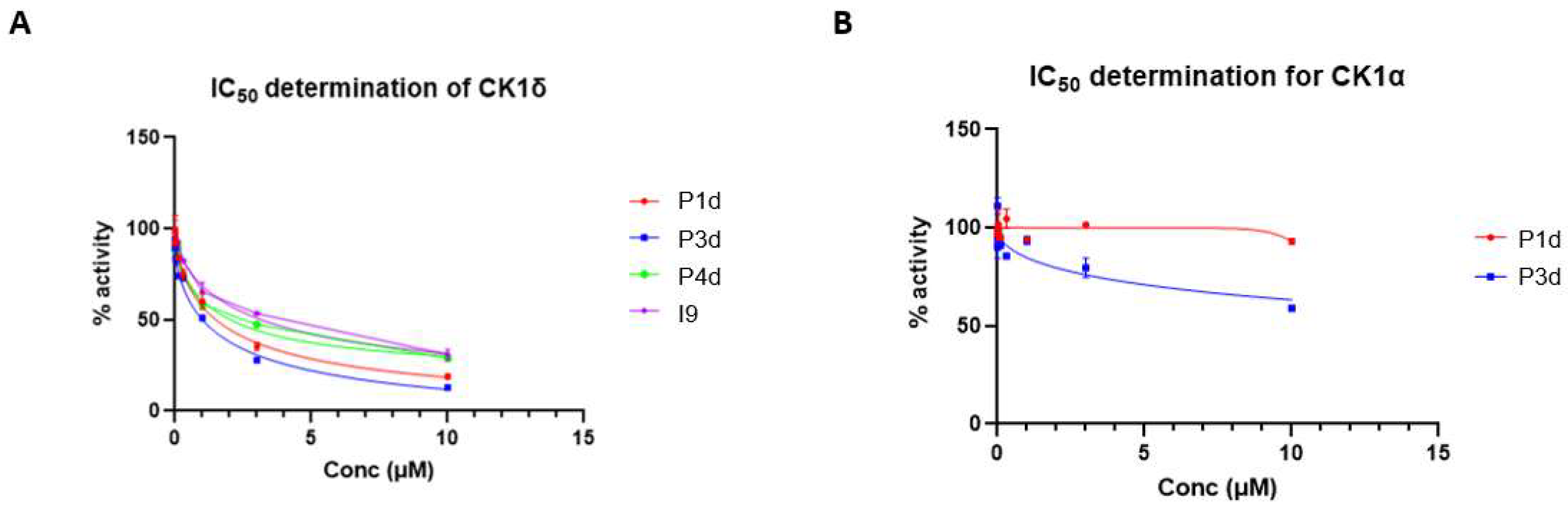

A key challenge in utilizing kinase inhibitors as warheads for PROTACs is that the PROTACs could still act as inhibitors even in the absence of degradation, and the effects of PROTACs on downstream biology might be due to inhibition, without the added benefit of degradation. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the relative contribution of inhibition vs degradation on downstream biology, as well as evaluate the potency of the kinase inhibition in vitro. For our top PROTAC P1d, an

in vitro kinase inhibition assay against CK1δ carried out in parallel with the inhibitor I9, showed IC

50 values of 2.16 μM compared to 3.43 μM for I9. These data suggested the potential of P1d to be a more potent cellular inhibitor of CK1δ/ε than I9. However, the superiority of P1d PROTAC at inhibiting downstream CK1δ/ε via degradation compared to inhibition comes from the observations when WT and CRBN-KO U2OS cells were treated with P1d. Here, P1d degrades CK1δ/ε in WT cells but not in CRBN-KO U2OS cells; however, it should still be able to inhibit CK1δ/ε activity in CRBN-KO cells. Excitingly, P1d-induced inhibition of both DVL3 and VANGL2 phosphorylation at both 5 μM and 10 μM in WT U2OS cells is much more potent than in CRBN-KO U2OS cells, suggesting that it is indeed the degradation of CK1δ/ε that accounts for the potent inhibition of downstream signalling. Nonetheless, 10 μM of P1d still potently inhibits DVL3 and VANGL2 phosphorylation in CRBN-KO U2OS cells, implying the compound enters the cells and inhibits CK1δ/ε, as no CK1δ/ε degradation is seen in CRBN-KO U2OS cells. Another exciting observation we made is that in A549 cells, P1d induced degradation of SACK1E (formerly FAM83E) but no other SACK1 proteins, although the functional significance of this needs further investigation. In cells it is known that CK1δ/ε exist in complex with SACK1A/FAM83A, SACK1B/FAM83B, SACK1E/FAM83E and SACK1H/FAM83H, but the function of SACK1E- CK1δ/ε complexes are unknown [

23].

The current minimum effective dose of P1d of 5 μM required to degrade CK1δ/ε does not compare favourably with more potent PROTACs against other targets that work at low nanomolar concentrations. This limitation is most likely due to the utilized CK1δ inhibitor moiety, which inhibits CK1δ in vitro with an IC50 of 3.43 μM. We aim to develop new series of compounds with a more potent inhibitor warhead, and alternative linkers as well as other E3 ligands, including those recruiting VHL, KLHDC2, and cIAP2. Based on the established procedures providing dimers containing E3 ligase ligands and linkers of varying motifs and lengths readily available, we aim to apply the modular platform for the preparation of further PROTAC sets towards various proteins of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., G.P.S. and C.P.; methodology, M.A., M.H., L.G. and T.T.; software, C.P.; validation, M.A., G.P.S. and C.P.; formal analysis, M.A., M.H., L.G. and T.T.; investigation, M.A., L.G. and T.T.; resources, M.A., G.P.S. and C.P.; data curation, M.A., M.H. L.G. and T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., G.P.S. and C.P; writing—review and editing, M.H., T.T., G.P.S. and C.P; visualization, M.A., G.P.S. and C.P.; supervision, G.P.S. and C.P.; project administration, M.A., G.P.S. and C.P.; funding acquisition, G.P.S. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the mechanism of action of PROTAC compounds. PROTACs hijack the UPS by forming ternary complexes with the POI and an E3 ligase, and therefore artificially inducing proximity between these proteins. The latter then recruits an E2 ligase, which transfers its ubiquitin molecules onto the POI. The polyubiquitinated POI is then marked for degradation by the 26S proteasome. Due to its catalytic nature, PROTACs can undergo this cycle of inducing polyubiquitination and degradation of a targeted POI in sub-stoichiometric amounts. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the mechanism of action of PROTAC compounds. PROTACs hijack the UPS by forming ternary complexes with the POI and an E3 ligase, and therefore artificially inducing proximity between these proteins. The latter then recruits an E2 ligase, which transfers its ubiquitin molecules onto the POI. The polyubiquitinated POI is then marked for degradation by the 26S proteasome. Due to its catalytic nature, PROTACs can undergo this cycle of inducing polyubiquitination and degradation of a targeted POI in sub-stoichiometric amounts. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Scheme 1.

a) Chemical structures of CK1α degrader probes, including both molecular glue (lenalidomide, TMX4116, SJ3149, DEG-77, CK1α degrader-1) and PROTAC (PROTAC 13i) compounds. b) Chemical structure of the CK1-“tear drop” inhibitor (MU1742) utilized to synthesize degrader compound AH078 containing an alkyl linker as well as a VHL ligand.

Scheme 1.

a) Chemical structures of CK1α degrader probes, including both molecular glue (lenalidomide, TMX4116, SJ3149, DEG-77, CK1α degrader-1) and PROTAC (PROTAC 13i) compounds. b) Chemical structure of the CK1-“tear drop” inhibitor (MU1742) utilized to synthesize degrader compound AH078 containing an alkyl linker as well as a VHL ligand.

SCHEME 2.

Combining relevant moieties from the chemical structures of IWP-2 and Bischof-5 led to the discovery of SMI 1, a highly CK1δ-specific and cellular effective inhibitor with an CK1δ IC50 value of 0.09 ± 0.01 μM.

SCHEME 2.

Combining relevant moieties from the chemical structures of IWP-2 and Bischof-5 led to the discovery of SMI 1, a highly CK1δ-specific and cellular effective inhibitor with an CK1δ IC50 value of 0.09 ± 0.01 μM.

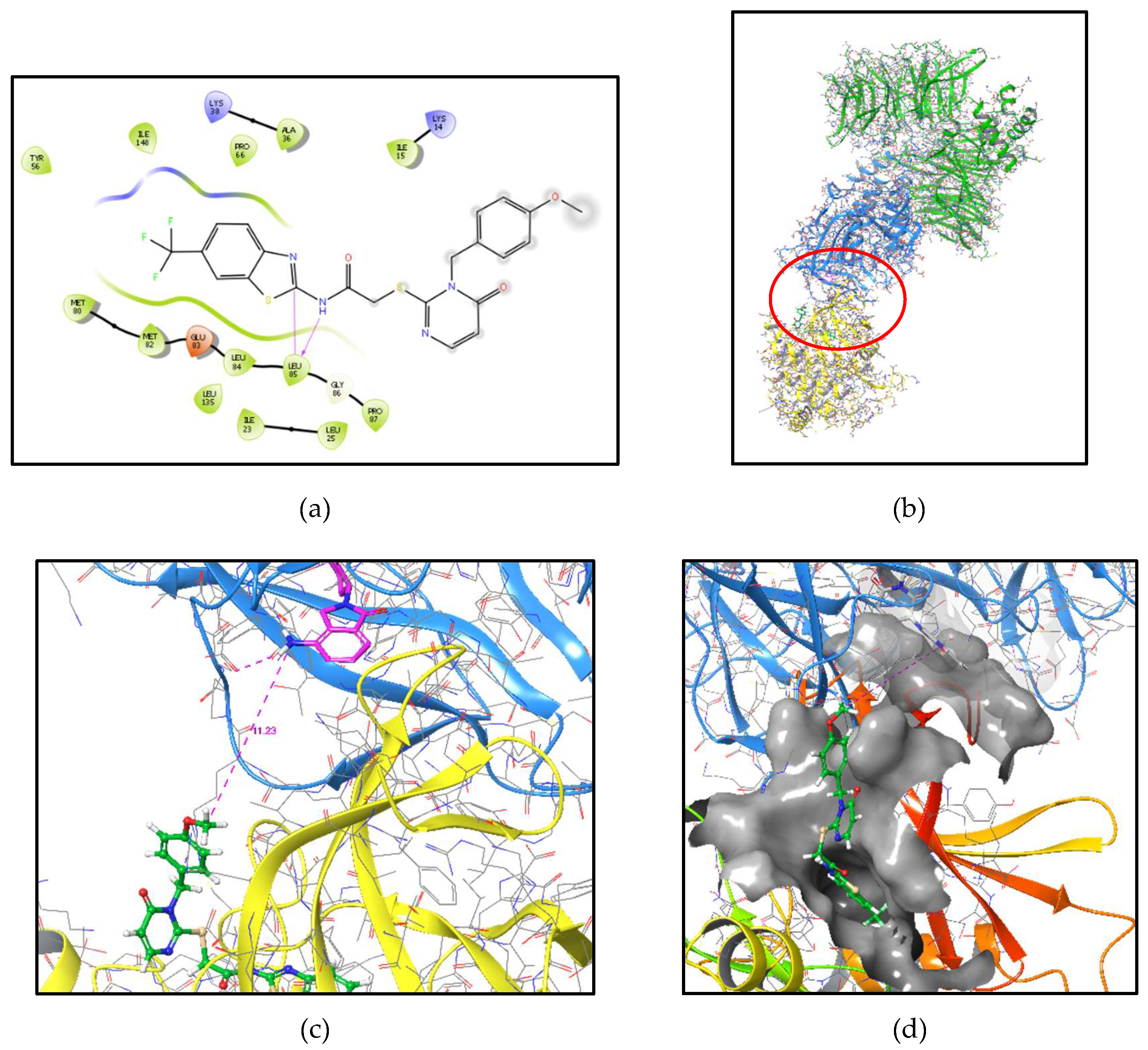

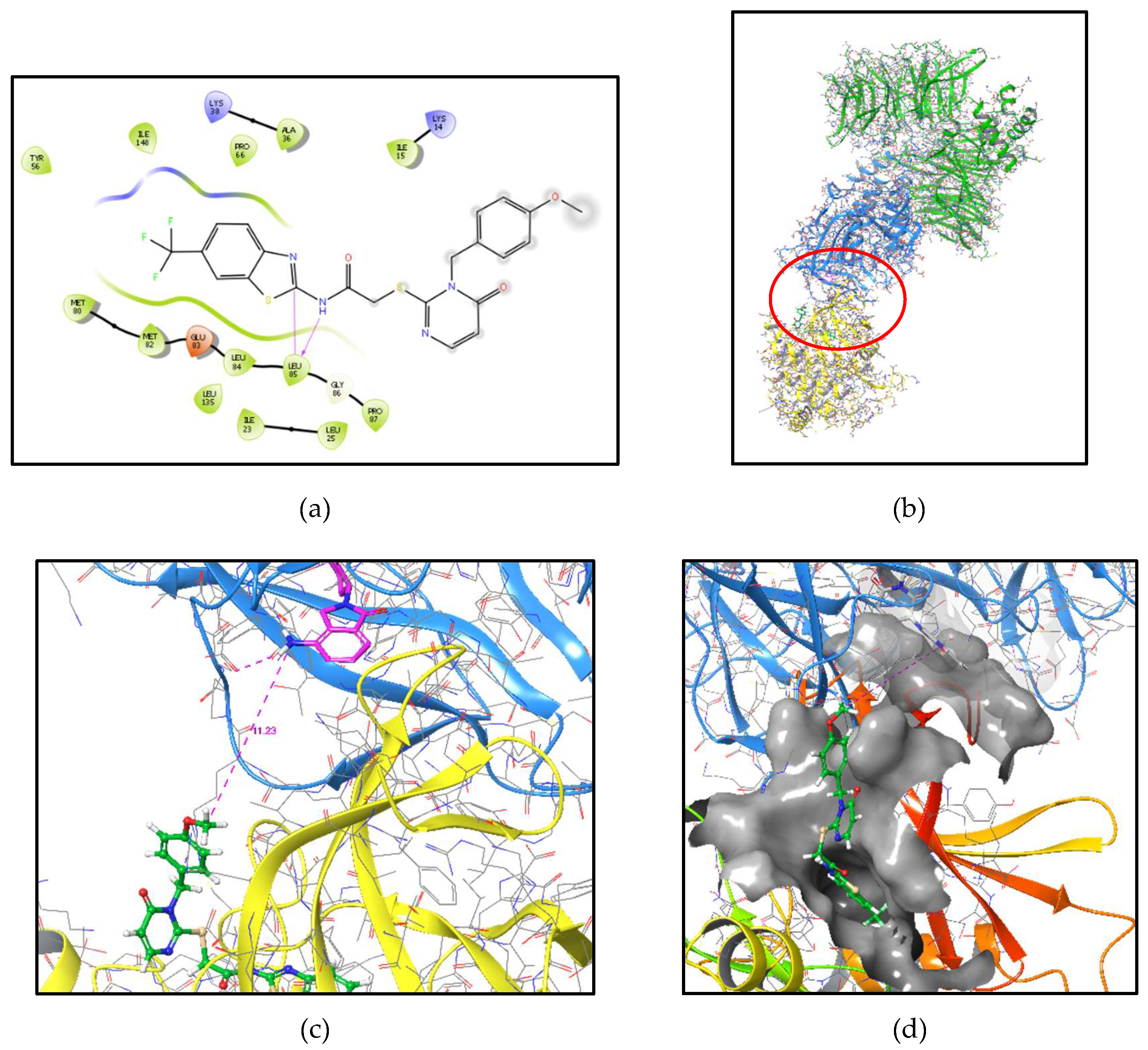

FIGURE 2.

Molecular modelling to guide the design of candidate CK1δ-PROTAC compounds.

a)

SMI 1 docked in the ATP binding pocket of CK1δ (pdb 5OKT) [

35] illustrated as a 2D-Ligand-interaction-diagram showing key interactions of the binding pose of

SMI 1 within the ATP pocket of CK1δ (bidental hinge-binding motif to Leu85 is highlighted). The benzyl moiety of

SMI 1 with the

p-MeO position is sitting in the solvent open area (grey dots), indicating this position to be suitable for linker attachment.

b) Molecular modelling based on a x-ray defined apoCK1α/CRL4(CRBN)/lenalidomide complex (pdb 5FQD) [

40]. We aligned CK1δ (pdb 5OKT, yellow) with docked

SMI 1 (green) in the ATP binding pocket on the original CK1α structure (not shown anymore) to generate a CK1δ (yellow) -

SMI 1 (green)/Crl4(CRBN) (blue/green) - lenalidomide (magenta) complex as a model system. The protein-interaction site of CK1δ-

SMI 1/CRBN-lenalidomide is highlighted

c) Close-up view of the highlighted area with the measured distance (dotted purple line) between the methyl group of the

p-MeO function of

SMI 1 (green) and the amino nitrogen atom of lenalidomide bound to CRL4(CRBN) (blue) revealed a linker length of approximately

d = 11 Å used for estimating the linker length of the designed CK1δ PROTACs in this study.

d) Close-up view of the highlighted area (side-perspective) also showing the solvent accessible protein surface.

FIGURE 2.

Molecular modelling to guide the design of candidate CK1δ-PROTAC compounds.

a)

SMI 1 docked in the ATP binding pocket of CK1δ (pdb 5OKT) [

35] illustrated as a 2D-Ligand-interaction-diagram showing key interactions of the binding pose of

SMI 1 within the ATP pocket of CK1δ (bidental hinge-binding motif to Leu85 is highlighted). The benzyl moiety of

SMI 1 with the

p-MeO position is sitting in the solvent open area (grey dots), indicating this position to be suitable for linker attachment.

b) Molecular modelling based on a x-ray defined apoCK1α/CRL4(CRBN)/lenalidomide complex (pdb 5FQD) [

40]. We aligned CK1δ (pdb 5OKT, yellow) with docked

SMI 1 (green) in the ATP binding pocket on the original CK1α structure (not shown anymore) to generate a CK1δ (yellow) -

SMI 1 (green)/Crl4(CRBN) (blue/green) - lenalidomide (magenta) complex as a model system. The protein-interaction site of CK1δ-

SMI 1/CRBN-lenalidomide is highlighted

c) Close-up view of the highlighted area with the measured distance (dotted purple line) between the methyl group of the

p-MeO function of

SMI 1 (green) and the amino nitrogen atom of lenalidomide bound to CRL4(CRBN) (blue) revealed a linker length of approximately

d = 11 Å used for estimating the linker length of the designed CK1δ PROTACs in this study.

d) Close-up view of the highlighted area (side-perspective) also showing the solvent accessible protein surface.

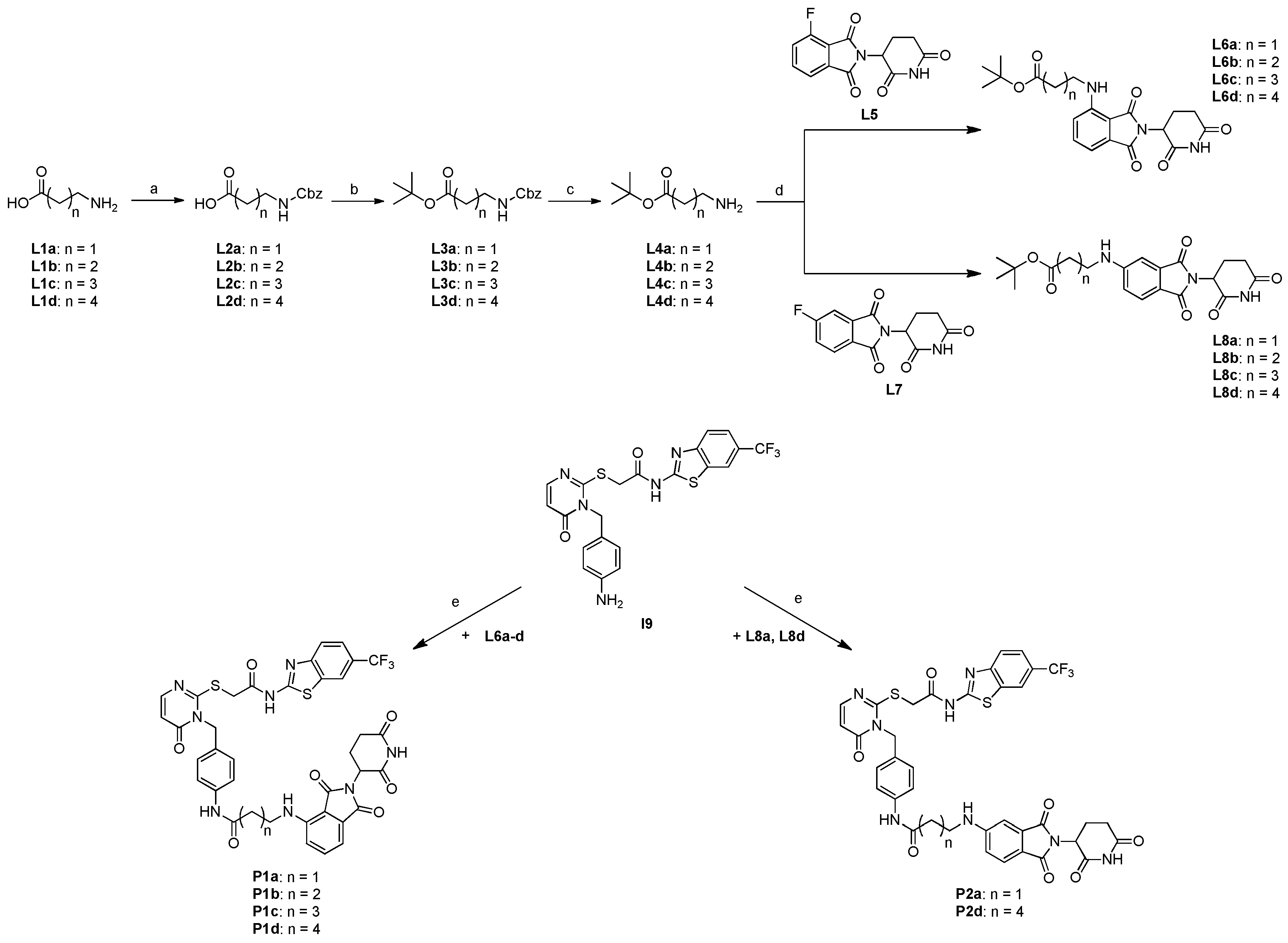

SCHEME 3.

Synthesis of POI ligand and intermediate I9. (a) 1.1 equiv. TEA in CH2Cl2, rt, 24 h; (b) 1.5 equiv. KOH and nano iron (cat.) in abs. DMSO under inert atmosphere, 110 °C, 2 h; (c) (i) 2.5 equiv. phenyl chlorothionoformate and 1.1 equiv. sodium bicarbonate in ethyl acetate/water (1:1), rt, overnight; (ii) 6.0 equiv. TEA in methanol, 80 °C, 4 h; (d) 3.0 equiv. TEA in abs. DMF, 80 °C, 2 h; (e) H2 (3 bar) and 10 % (m/m) Pd/C in methanol, rt, 24 h.

SCHEME 3.

Synthesis of POI ligand and intermediate I9. (a) 1.1 equiv. TEA in CH2Cl2, rt, 24 h; (b) 1.5 equiv. KOH and nano iron (cat.) in abs. DMSO under inert atmosphere, 110 °C, 2 h; (c) (i) 2.5 equiv. phenyl chlorothionoformate and 1.1 equiv. sodium bicarbonate in ethyl acetate/water (1:1), rt, overnight; (ii) 6.0 equiv. TEA in methanol, 80 °C, 4 h; (d) 3.0 equiv. TEA in abs. DMF, 80 °C, 2 h; (e) H2 (3 bar) and 10 % (m/m) Pd/C in methanol, rt, 24 h.

SCHEME 4.

Synthesis of the first set of PROTAC compounds P1a-d, as well as P2a and P2d containing alkyl linker motifs. (a) 1.1 equiv. benzyl chloroformate in 2 N sodium hydroxide solution, rt, overnight; (b) 1.1 equiv. phosphoryl chloride in tBuOH/Pyridine (3:2), rt, overnight; (c) H2 and 10 % (m/m) Pd/C in methanol, rt, overnight; (d) 3.0 equiv. DIPEA in DMSO, 90 °C, 14 h; (e) (i) 1 mL TFA in CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h; (ii)1.0 equiv. EDC x HCl, 0.1 equiv. HOBt, 1.0 equiv. DMAP and 5.0 equiv. DIPEA in MeCN, rt, 48 h.

SCHEME 4.

Synthesis of the first set of PROTAC compounds P1a-d, as well as P2a and P2d containing alkyl linker motifs. (a) 1.1 equiv. benzyl chloroformate in 2 N sodium hydroxide solution, rt, overnight; (b) 1.1 equiv. phosphoryl chloride in tBuOH/Pyridine (3:2), rt, overnight; (c) H2 and 10 % (m/m) Pd/C in methanol, rt, overnight; (d) 3.0 equiv. DIPEA in DMSO, 90 °C, 14 h; (e) (i) 1 mL TFA in CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h; (ii)1.0 equiv. EDC x HCl, 0.1 equiv. HOBt, 1.0 equiv. DMAP and 5.0 equiv. DIPEA in MeCN, rt, 48 h.

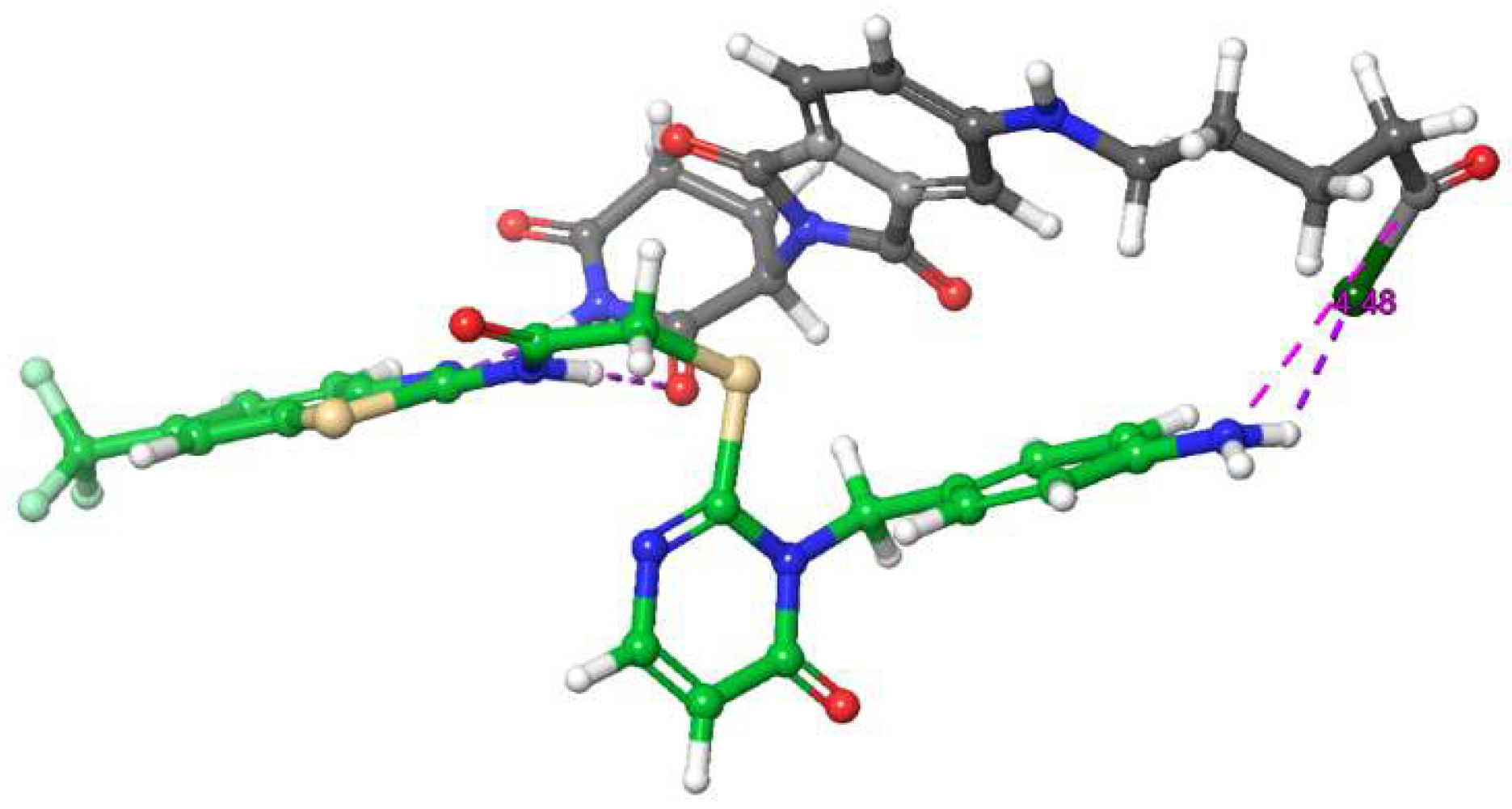

FIGURE 3.

Exemplary molecular modelling suggesting complex-forming interactions between I9 and L8c, thereby potentially preventing the amide coupling reaction.

FIGURE 3.

Exemplary molecular modelling suggesting complex-forming interactions between I9 and L8c, thereby potentially preventing the amide coupling reaction.

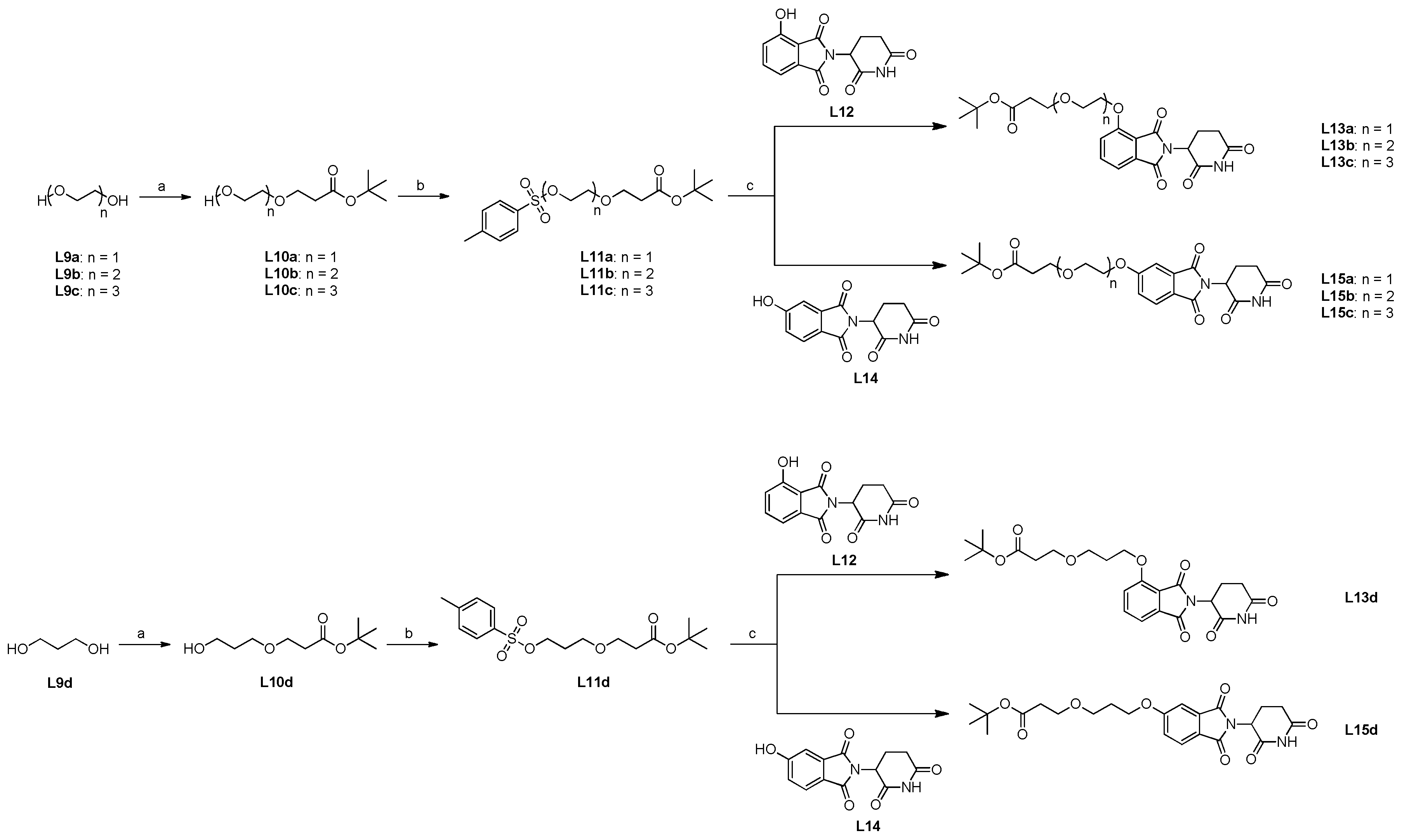

Scheme 5.

Synthesis for compounds L13a-d and L15a-d containing PEG linker motifs. (a) 1.0 equiv. tert-butyl acrylate and 0.04 equiv. Triton B solution (40 % in water), rt, 120 h; (b) 1.5 equiv. 3.0 equiv. TEA and 0.1 equiv. DMAP in CH2Cl2, rt. 24 h; (c) 1.5 equiv. potassium bicarbonate and 0.1 equiv. sodium iodide in DMF, 80 °C, 16 h.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis for compounds L13a-d and L15a-d containing PEG linker motifs. (a) 1.0 equiv. tert-butyl acrylate and 0.04 equiv. Triton B solution (40 % in water), rt, 120 h; (b) 1.5 equiv. 3.0 equiv. TEA and 0.1 equiv. DMAP in CH2Cl2, rt. 24 h; (c) 1.5 equiv. potassium bicarbonate and 0.1 equiv. sodium iodide in DMF, 80 °C, 16 h.

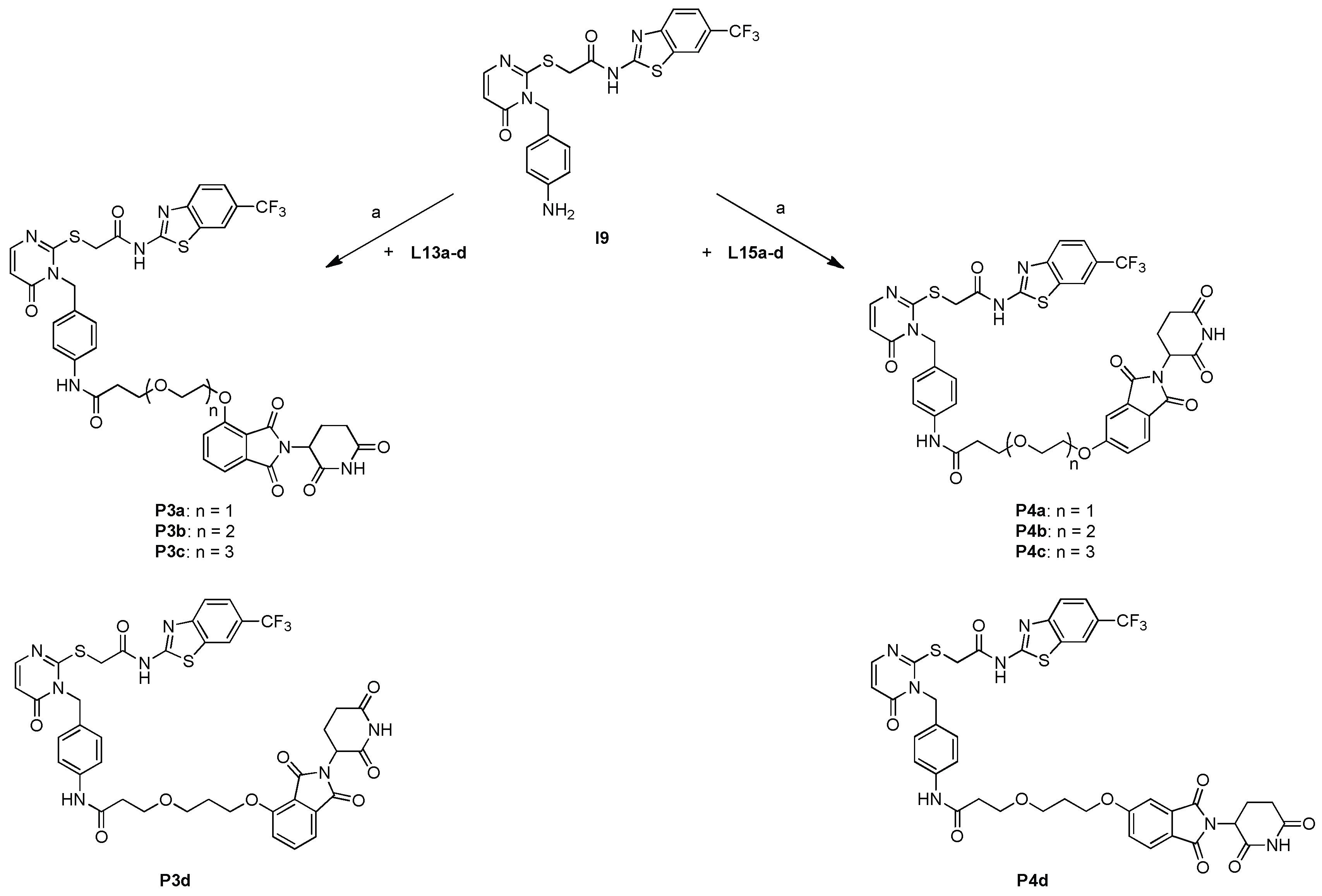

SCHEME 6.

Synthesis for the second and third set of PROTAC compounds P3a-d and P4a-d containing PEG linker motifs. (a) (i) 1 mL TFA in CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h; (ii)1.0 equiv. EDC x HCl, 0.1 equiv. HOBt, 1.0 equiv. DMAP and 5.0 equiv. DIPEA in MeCN, rt, 48 h.

SCHEME 6.

Synthesis for the second and third set of PROTAC compounds P3a-d and P4a-d containing PEG linker motifs. (a) (i) 1 mL TFA in CH2Cl2, rt, 1 h; (ii)1.0 equiv. EDC x HCl, 0.1 equiv. HOBt, 1.0 equiv. DMAP and 5.0 equiv. DIPEA in MeCN, rt, 48 h.

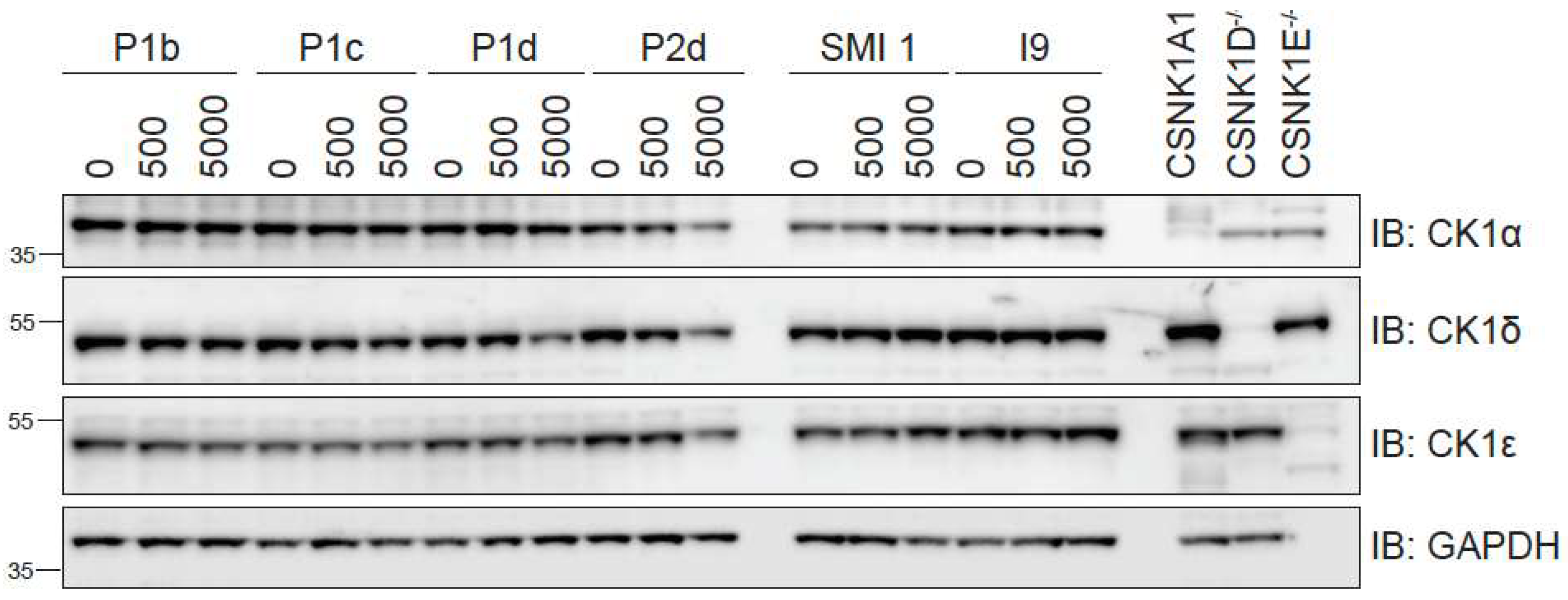

FIGURE 4.

Dose response of PROTAC compounds P1b, P1c, P1d & P2d at 0.5 and 5 μM. Wildtype (WT) U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, I9, SMI 1, or the indicated PROTACs at 0.5 and 5 μM for 24 h prior to lysis. Extracts (20 µg) were resolved by 4-20% Bis-Tris pre-cast SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was employed as a loading control. Extracts from DLD-1 CSNK1A1-/-, CSNK1D-/- and CSNK1E-/- cells were included to validate CK1α, CK1δ and CK1ε antibodies respectively. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

FIGURE 4.

Dose response of PROTAC compounds P1b, P1c, P1d & P2d at 0.5 and 5 μM. Wildtype (WT) U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, I9, SMI 1, or the indicated PROTACs at 0.5 and 5 μM for 24 h prior to lysis. Extracts (20 µg) were resolved by 4-20% Bis-Tris pre-cast SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was employed as a loading control. Extracts from DLD-1 CSNK1A1-/-, CSNK1D-/- and CSNK1E-/- cells were included to validate CK1α, CK1δ and CK1ε antibodies respectively. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

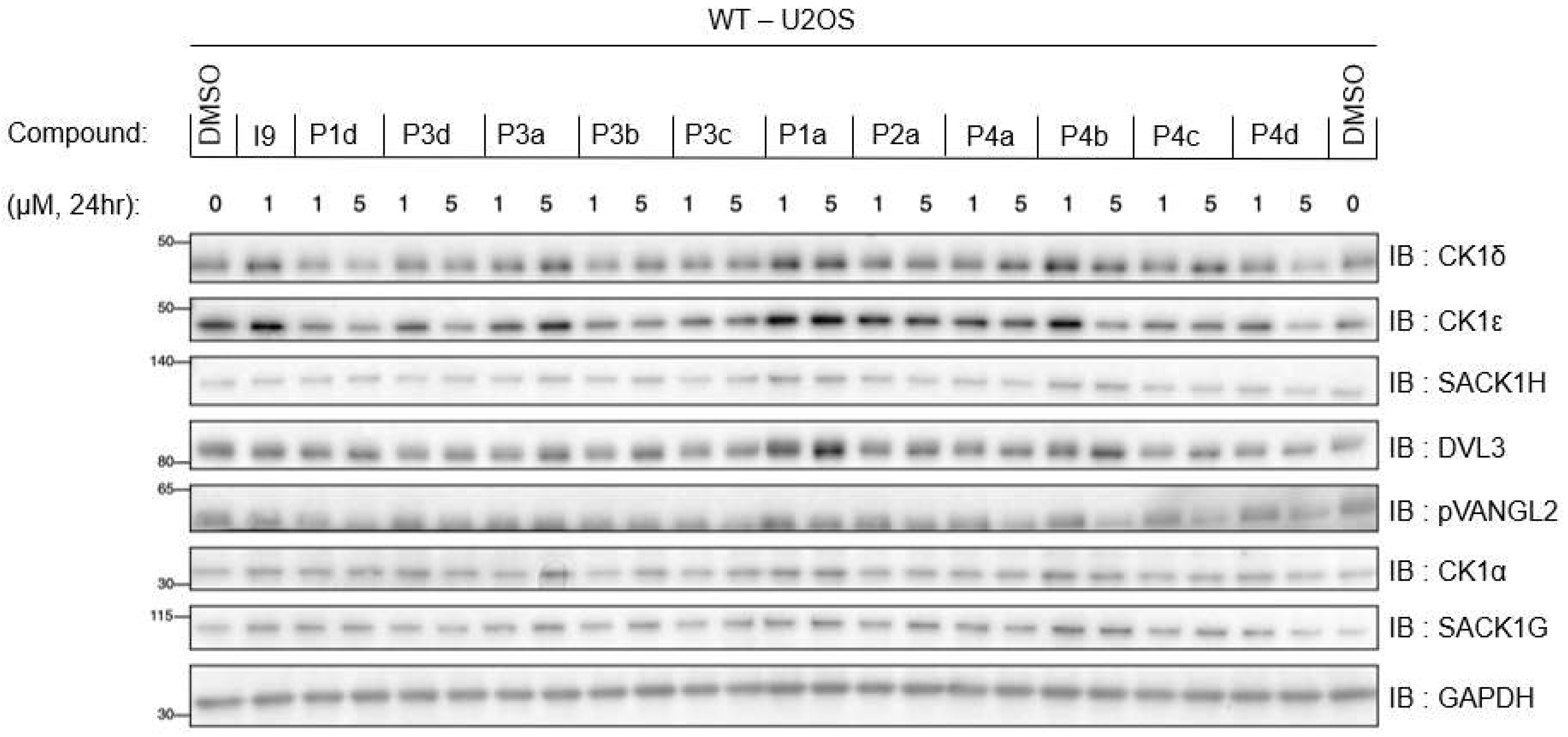

FIGURE 5.

Dose response of all PROTAC compounds at 1 and 5 μM. Wildtype (WT) U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, reference inhibitor I9 at 1 μM, or indicated PROTACs (P1d to P4d) at 1 and 5 μM for 24 h prior to lysis. Extracts (20 µg) were resolved by 4-20% Bis-Tris pre-cast SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was employed as a loading control. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

FIGURE 5.

Dose response of all PROTAC compounds at 1 and 5 μM. Wildtype (WT) U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, reference inhibitor I9 at 1 μM, or indicated PROTACs (P1d to P4d) at 1 and 5 μM for 24 h prior to lysis. Extracts (20 µg) were resolved by 4-20% Bis-Tris pre-cast SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was employed as a loading control. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

FIGURE 6.

In vitro IC50 determination for the indicated compounds in vitro against CK1δ (A) and CK1α (B) kinase activity using a peptide substrate. All assays performed by the MRC PPU International Centre for Kinase Profiling.

FIGURE 6.

In vitro IC50 determination for the indicated compounds in vitro against CK1δ (A) and CK1α (B) kinase activity using a peptide substrate. All assays performed by the MRC PPU International Centre for Kinase Profiling.

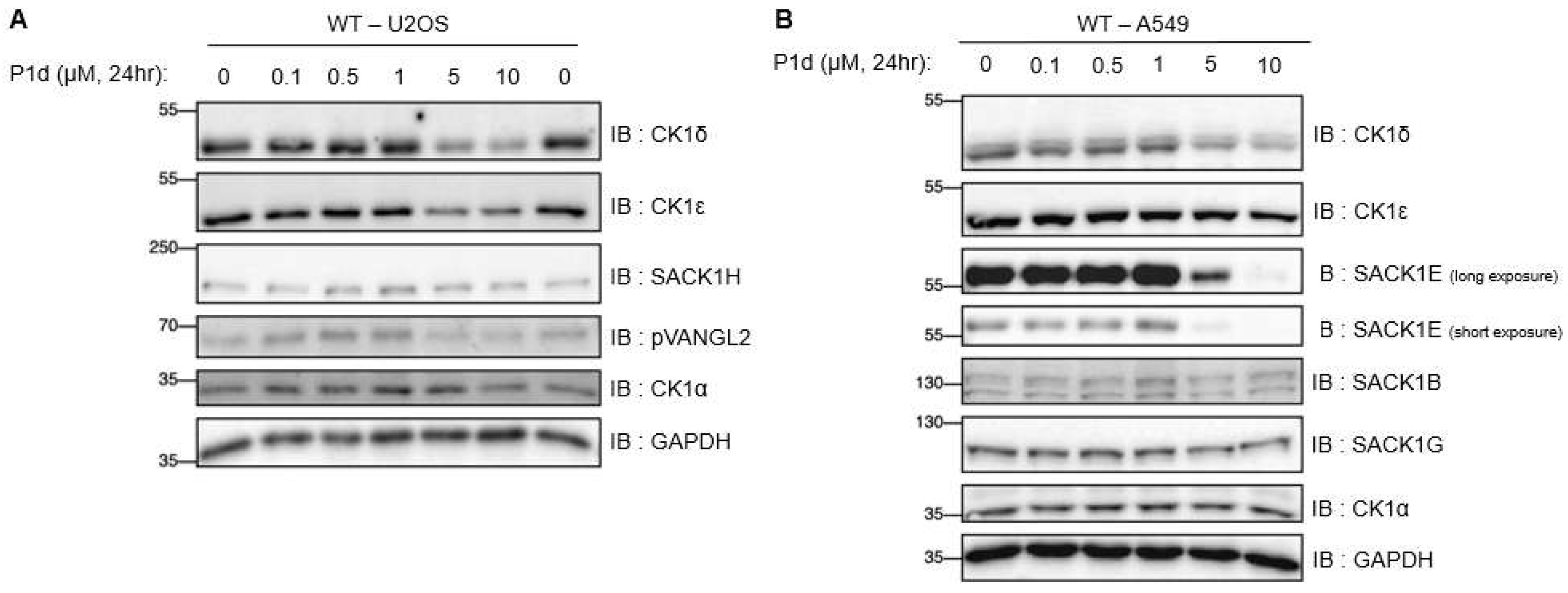

FIGURE 7.

Dose response of compound P1d at 0-10μM in various cell lines. (A) Wildtype (WT) U2OS, and (B) A549 adenocarcinoma cells were treated with DMSO or P1d (from 0.1-10 µM) for 24 h prior to lysis. Extracts (20 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

FIGURE 7.

Dose response of compound P1d at 0-10μM in various cell lines. (A) Wildtype (WT) U2OS, and (B) A549 adenocarcinoma cells were treated with DMSO or P1d (from 0.1-10 µM) for 24 h prior to lysis. Extracts (20 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

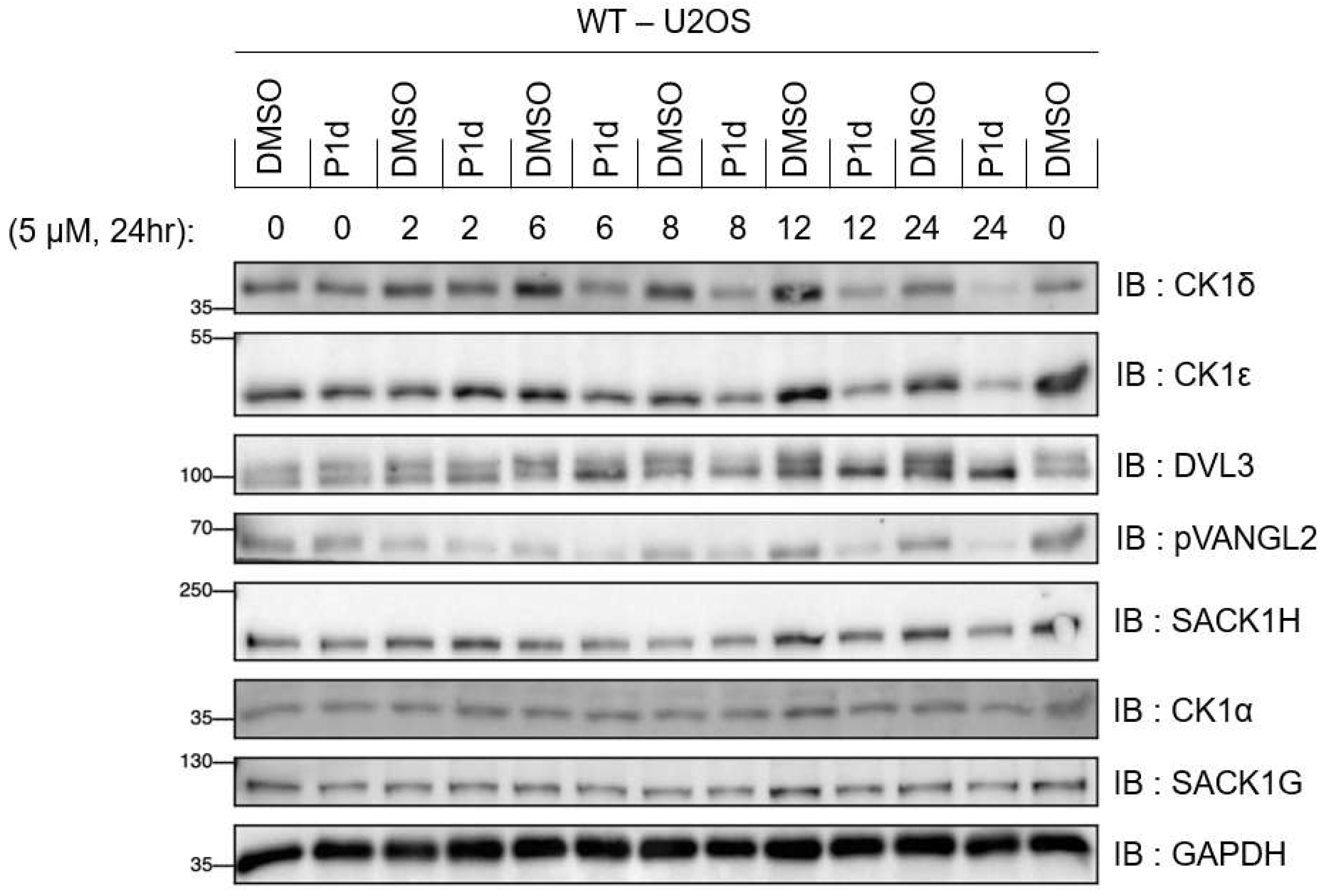

FIGURE 8.

Kinetic analysis of CK1δ/ε degradation by compound P1d at 5 μM. Wildtype (WT) U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, or 5 μM P1d for the indicated times prior to lysis. Extracts (20 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

FIGURE 8.

Kinetic analysis of CK1δ/ε degradation by compound P1d at 5 μM. Wildtype (WT) U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, or 5 μM P1d for the indicated times prior to lysis. Extracts (20 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

FIGURE 9.

Mode of E3 ligase action compound P1d at 5 and 10μM. A) Wildtype (WT) or CRBN-knock out (CRBN - KO) U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, or P1d at 5 and 10 µM for 24 h prior to lysis. (B) WT U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, or P1d at 5 µM without or together with 1 µM MLN4924 (NAE1 inhibitor) or 20 µM of MG132 (proteasome inhibitor). For A & B, extracts (20 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

FIGURE 9.

Mode of E3 ligase action compound P1d at 5 and 10μM. A) Wildtype (WT) or CRBN-knock out (CRBN - KO) U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, or P1d at 5 and 10 µM for 24 h prior to lysis. (B) WT U2OS cells were treated with DMSO, or P1d at 5 µM without or together with 1 µM MLN4924 (NAE1 inhibitor) or 20 µM of MG132 (proteasome inhibitor). For A & B, extracts (20 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies. All blots are representative of three independent biological repeats.

Table 1.

Employed conditions in order to try to generate compounds P2b-c.

Table 1.

Employed conditions in order to try to generate compounds P2b-c.

| I9 |

L8b-c |

Solvent |

Base

(5 equiv.) |

Coupling Reagents |

Temperature [° C] |

Reaction Time |

Additive |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

DMSO |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

DMF |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

THF |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

25 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

Potassium carbonate |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

TEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DBU |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

Mole sieve (3 Å) |

| 2 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

2 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

Glutarimide (5 equiv.) |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

EDC, HOBT, DMAP |

40 °C |

48 h |

Glutarimide (10 equiv.) |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

HATU |

40 °C |

5 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

Potassium carbonate |

HATU |

40 °C |

5 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

TEA |

HATU |

40 °C |

5 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DBU |

HATU |

40 °C |

5 h |

- |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

HATU |

40 °C |

5 h |

Mole sieve (3 Å) |

| 1 equiv. |

1 equiv. |

MeCN |

DIPEA |

HATU |

70 °C |

5 h |

- |

Table 1.

Overview of Compounds and Corresponding Linker Lengths.

Table 1.

Overview of Compounds and Corresponding Linker Lengths.

| PROTAC |

Linker length (Å)1

|

| P1a |

4.179 |

| P1b |

4.991 |

| P1c |

6.428 |

| P1d |

7.413 |

| P2a |

4.179 |

| P2d |

7.413 |

| P3a |

7.103 |

| P3b |

10.712 |

| P3c |

14.062 |

| P3d |

8.492 |

| P4a |

7.103 |

| P4b |

10.712 |

| P4c |

14.062 |

| P4d |

8.492 |