1. Introduction

Previous research has established that calcium-permeable kainate and AMPA receptors (CP-KARs and CP-AMPARs) are predominantly expressed in hippocampal GABAergic neurons of adult rats [

1]. These receptors define two major subgroups of neurons, which together constitute over 55% of the GABAergic population [

1,

2]. One group expresses CP-KARs, and the other expresses CP-AMPARs [

1,

2,

3,

4]. CP-AMPAR-expressing GABAergic neurons innervate those expressing CP-KARs, and to a lesser extent, the reverse is also true [

1,

2,

5]. Functionally, these receptors act as low-threshold ion channels, enabling neurons to be excited by weak depolarizations or low concentrations of agonists like domoic acid (DoA) [

1,

3]. For instance, GABAergic neurons expressing these receptors generate a sodium current at approximately -55 mV, a potential requiring only minimal depolarization. In contrast, glutamatergic neurons typically require a stronger depolarization to reach their excitation threshold of around -42 mV [

3]. Agonists like ATPA (targeting GluR5 subunits of CP-KARs) or SYM2081 selectively increase intracellular calcium in CP-KAR-expressing neurons, induce GABA release, and consequently suppress the activity of downstream neurons [

5,

6,

7,

8]. These properties have even been leveraged to develop methods for visualizing these specific neurons in culture [

3,

9]. Notably, during DoA exposure, these GABAergic neurons exhibit a unique response: they are not fully excited to fire action potentials. Instead, calcium influx through CP-KARs reaches a subthreshold level that is sufficient to trigger GABA release directly.

This functional profile aligns with that of low-threshold spiking (LTS) interneurons, which are known to provide advanced inhibition and are excited by small shifts in membrane potential [

10,

11]. While classic feedforward inhibition in LTS interneurons is often attributed to T-type calcium channels (also activated at -55 mV), the receptor-mediated mechanism described here provides an alternative pathway. It is important to note a discrepancy in the population size: while LTS interneurons are estimated to comprise 4.5-15% of hippocampal GABAergic neurons [

25], our data indicate that over 55% express CP-KARs or CP-AMPARs in culture [

1]. This suggests that these low-threshold receptor phenotypes may be more widespread among GABA neurons than the defined LTS interneuron subtype.

This study demonstrates that GABAergic neurons expressing CP-KARs and CP-AMPARs respond earlier than glutamatergic neurons, both to depolarization and to glutamate receptor agonists in slices of the hippocampus from adult two-month-old animals. Thus, the mechanisms of the preliminary reaction of GABAergic neurons and the delay in the excitation of other neurons are realized in the brains of adult animals.

3. Discussion

The present work is devoted to demonstrating the existence of a leading reaction to excitation of GABAergic neurons in slices of the adult animal hippocampus and to investigating the role of GABAergic neurons expressing CP-AMPARs or CP-KARs in the early signal to glutamate receptor agonists and depolarization.

It is believed that the level of excitation of glutamatergic neurons is controlled by inhibitory neurons. However, for effective control, a feedforward response mechanism by inhibitory neurons to excitation is required.

Evidence for such a feedforward response in GABAergic neurons has been demonstrated upon application of glutamate receptor agonists or depolarization [

1,

3]

.

Several studies have described a minor subtype of low-threshold spiking (LTS) interneurons in the hippocampus that provide feedforward inhibition [

11]. These neurons are also considered low-threshold. The authors believe that the feedforward action of LTS interneurons is mediated by the response of T-type Ca

2+ channels (which are activated at -55mV and cause slow calcium spikes). When DoA acts, initial excitation of GABAergic neurons does not occur, but [Ca

2+]

i increases due to influx through the CP-KARs receptor, which induces GABA release. LTS interneurons constitute 4,5-15% of all GABAergic neurons in the hippocampus [

25]. Whereas GABAergic neurons expressing CP-KARs and CP-AMPARs (according to our data, constitute more than half of GABAergic neurons in hippocampal culture [

1]. Therefore, it can be argued that the vast majority of inhibitory neurons exhibit a feedforward response to excitation, using low-threshold CP-KARs and CP-AMPARs.

This study aims to demonstrate the existence of a rapid, feedforward response in adult hippocampal GABAergic neurons and to investigate the role of calcium-permeable AMPARs and KARs (CP-AMPARs/CP-KARs) in mediating this response.

Neural circuit stability requires inhibitory neurons to control glutamatergic excitation. For maximum effectiveness, this control must involve a feedforward response, where inhibitory neurons are among the first to be activated. Evidence for such a feedforward response in GABAergic neurons has been shown in culture models [

1,

3]. A known candidate for this role is the low-threshold spiking (LTS) interneuron, which constitutes 4.5-15% of GABAergic neurons and operates via T-type calcium channels [

11,

25]. While LTS interneurons has been implicated in feedforward inhibition via T-type calcium channels [

11,

25], this mechanism cannot account for the widespread rapid responses we and others have observed in culture [

1,

3].

In contrast, we propose a more widespread mechanism: GABAergic neurons expressing CP-AMPARs and CP-KARs, which our data indicate represent over half of the GABAergic population in culture [

1]. In our proposed model, CP-KARs on GABAergic neurons are activated at resting potentials. This allows for direct calcium influx through receptors like CP-KARs upon agonist binding, triggering immediate GABA release without requiring prior depolarization. Therefore, we suggest that the predominant mechanism for feedforward inhibition involves CP-KARs, enabling a rapid response from the majority of inhibitory neurons and presents a fundamental and widespread mechanism for rapid inhibitory control.

GABAergic neurons in hippocampal culture can be classified into two subtypes based on their expression of either calcium-permeable KARs (CP-KARs) or CP-AMPARs [

1,

9,

12]. These receptors are characterized by their high agonist affinity and sensitivity to depolarization, making them low-threshold sensors for excitation [

1,

3]. This property enables GABAergic neurons to generate a rapid, feedforward response to excitatory stimuli. Depolarization and agonist binding triggers a selective Ca²⁺ rise in these neurons, leading to immediate GABA release [

5,

6,

7] and subsequent inhibition of downstream neuronal activity. The resulting delay in network excitation is primarily mediated by postsynaptic hyperpolarization via GABA(A) receptors, a conclusion supported by the abolition of the delay with the antagonist bicuculline (Fig. 2A). Thus, the feedforward inhibitory capability of these GABAergic neurons stems directly from the low-threshold properties of CP-KARs and CP-AMPARs.

The duration of the delay in glutamatergic neuron excitation varies significantly across the population (

Figure 2B). This heterogeneity may be explained by differences in the chloride ion gradient among target neurons, which determines whether GABA(A) receptor activation results in hyperpolarization or depolarization [

19]. Variations in this gradient would lead to differing degrees of GABA(A)R-dependent inhibition, thus accounting for the observed spectrum of delays and potentially contributing to neuronal desynchronization. Furthermore, the specific neural circuit involving the two GABAergic subtypes is critical. We previously showed that GABAergic neurons expressing CP-AMPARs innervate and inhibit those expressing CP-KARs [

1,

2,

5]. Therefore, when NBQX blocks CP-AMPARs, it likely

disinhibits the CP-KAR-expressing GABAergic neurons. This disinhibition enhances GABA release from these neurons onto their glutamatergic targets, thereby

increasing the excitation delay (

Figure 3A). This mechanism indicates that while both GABAergic subtypes respond early to DoA, the delay in glutamatergic excitation is predominantly controlled by the activity of CP-KAR-expressing neurons. This conclusion is supported by the observation that NBQX-mediated inhibition of CP-AMPARs, which removes a source of inhibition from the CP-KAR-expressing neurons, results in a longer delay.

The delay in glutamatergic excitation is primarily determined by the duration of GABAergic inhibition, as evidenced by its abolition with bicuculline. The latency is influenced by several factors, including the timing of GABA reuptake, individual neuronal chloride gradients, and the strength of the concurrent depolarizing current. DoA induces a biphasic response: an initial hyperpolarization via GABA release followed by a slow depolarization, likely mediated by calcium-impermeable AMPA receptors. Excitation occurs when this slow depolarization eventually reaches the threshold for sodium and calcium channel activation. Consequently, the net latency depends on the balance between the inhibitory GABAergic force and the magnitude of the slow depolarizing current, which is agonist concentration-dependent (Fig. 3C). This explains the inverse relationship between agonist concentration and delay duration observed in

Figure 3; higher concentrations produce a stronger depolarizing current, overcoming the inhibition more quickly. A second mechanism influencing delay may involve a calcium-buffering system within CP-AMPAR-expressing GABAergic neurons. We propose that these neurons exhibit a delayed response until their intrinsic calcium-binding proteins are saturated. Once saturated, these neurons would then inhibit the CP-KAR-expressing GABAergic neurons. This

disinhibition of the glutamatergic neurons targeted by CP-KAR cells, combined with the ongoing slow depolarization, would render them highly excitable and capable of generating low-amplitude, high-frequency oscillations. This represents a form of short-term plasticity that enhances the activity of a specific neuronal population.

Finally, the early-response property of neurons expressing CP-KARs/CP-AMPARs is not specific to DoA. As shown in Figures 4A, C, and D, these neurons also respond ahead of the main population to glutamate itself. Interestingly, a small subpopulation of glutamatergic neurons also exhibits an early response to glutamate (Figs. 4A, C). In contrast to the GABAergic neurons, however, these glutamatergic cells display asynchronous oscillatory responses.

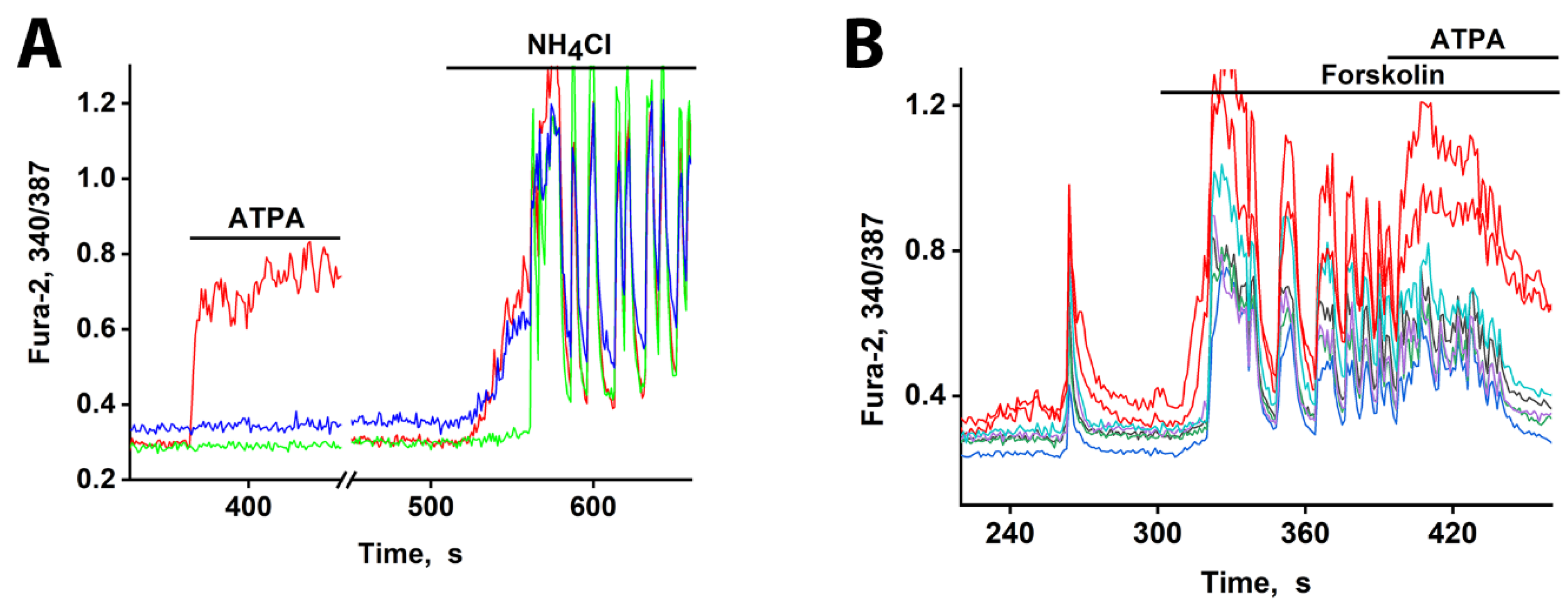

To confirm the low-threshold excitability of GABAergic neurons expressing CP-KARs and CP-AMPARs, we applied a moderate depolarization (10-12 mV) using NH₄Cl. As shown in

Figure 5A, both neuronal subtypes responded ahead of the general population, consistent with previous findings [

1,

3]. A key characteristic of these receptors is their low conductance, which allows subthreshold depolarization to elevate intracellular Ca²⁺ and trigger GABA release without necessarily generating action potentials.

We next tested neuronal responses under conditions of enhanced network excitability. Forskolin, a strong activator of adenylate cyclase, increases intracellular cAMP levels. This leads to PKA-dependent phosphorylation, which promotes depolarization by enhancing the activity of Ca²⁺ and Na⁺ channels while suppressing hyperpolarizing K⁺ channels. As expected, forskolin induced strong network-wide activation (increased firing frequency) in mature hippocampal cultures (

Figure 5B). Under these conditions, a subset of neurons responded more rapidly. The subsequent application of ATPA (200 nM) induced a [Ca²⁺]

i increase specifically in these early-responding cells, identifying them as GABAergic neurons expressing CP-KARs. This rapid response to forskolin looks like the effect of other weak depolarizing agents [

23,

26], confirming that CP-KAR-expressing neurons are capable for early activation under various excitatory conditions.

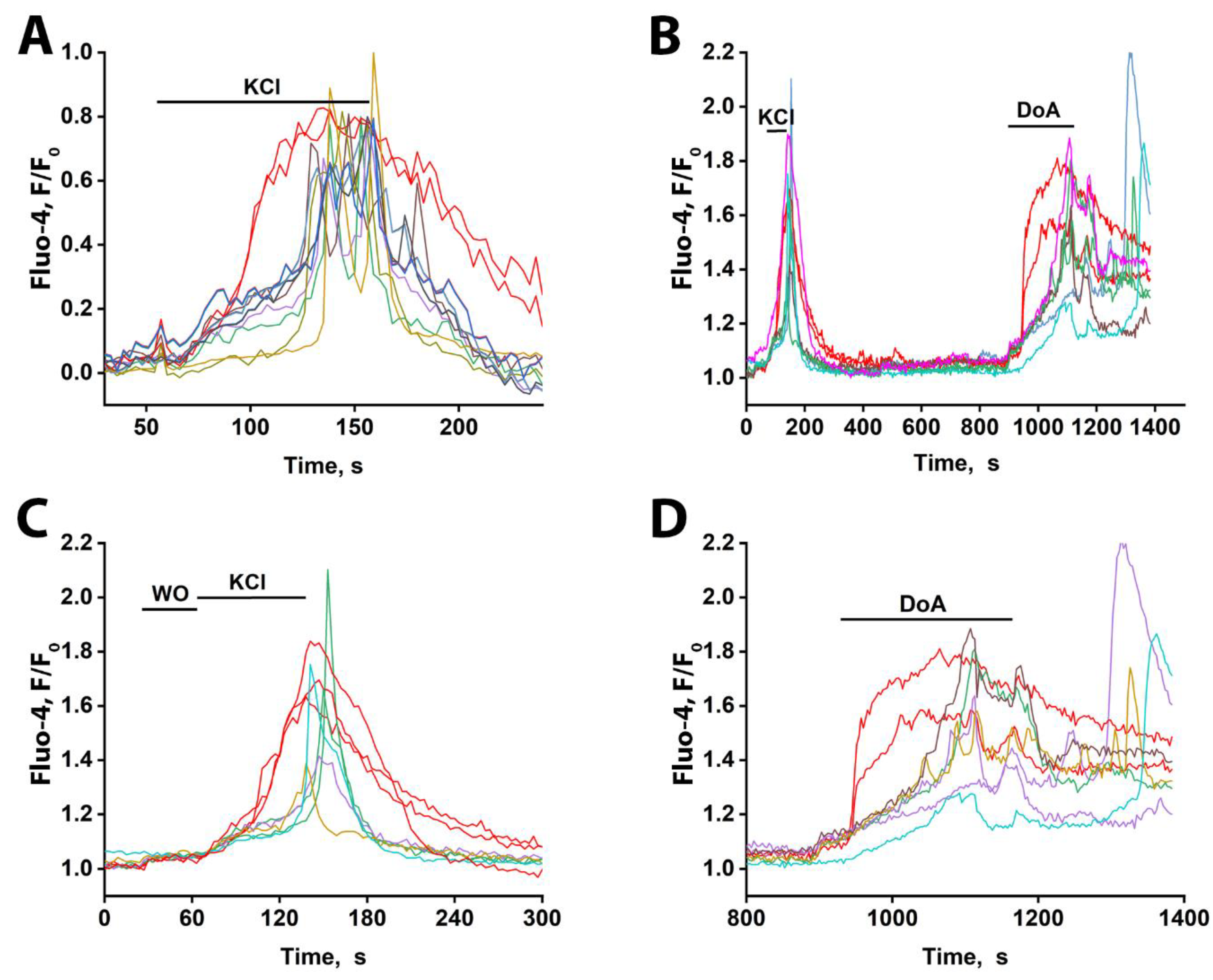

To determine if this mechanism of excitation control operates in a more native context, we performed experiments on hippocampal slices from two-month-old animals.

Figure 6 demonstrates that a small population of neurons in these slices exhibits a leading response to both depolarization and DoA, analogous to our culture findings. The same neurons responded more quickly to both stimuli, indicating the presence of an anticipatory GABAergic mechanism in vivo. This mechanism likely regulates hyperexcitability caused by depolarizing shifts and prevents the synchronization of glutamatergic networks.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture Preparation

Primary neuronal-glial co-cultures were prepared from the hippocampi of neonatal Wistar rats (postnatal days 0–2). Briefly, after decapitation, hippocampal tissue was rapidly dissected into cold Versene solution, minced, and digested with 1% trypsin for 10 minutes at 37 °C under continuous agitation (~500 rpm). The digested tissue was then washed with chilled Neurobasal medium and mechanically dissociated by gentle trituration. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 3 minutes, and the pellet was resuspended in culture medium (Neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B27, 0.5 mM glutamine, 1:250 penicillin-streptomycin). To optimize conditions for postnatal neurons, the NaCl concentration was adjusted to 4 g/L, matching that of Neurobasal-A medium.

For plating, 100 μL aliquots of the cell suspension were placed within glass cylinders (6 mm inner diameter, 7 mm height) positioned on polyethyleneimine-coated glass coverslips in Petri dishes. The cultures were incubated for 40 minutes (37°C, 5% CO₂, 95% humidity) to allow for cell attachment, after which the cylinders were carefully removed, and 2 mL of complete medium was added to each dish. Cultures were maintained with partial medium replacement (one-third volume) every four days and used for experiments after 13–14 days in vitro (DIV).

4.2. Hippocampal Sliсes

Hippocampal slices were obtained from two-month-old male Sprague-Dawley rats. The rats were subjected to terminal anesthesia by inhalation overdose of halothane, after which the brain was extracted and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal medium (aCSF) with the following composition: 124 mM NaCl, 26 mM NaHCO₃, 3 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl₂, 1.25 mM NaH₂PO₄, 1 mM MgSO₄, 10 mM glucose, saturated with a mixture of 95% O₂ and 5% CO₂ (pH 7.4) with 9 mM Mg²⁺.

Coronal slices of the CA1 region of the hippocampus, 300 μm thick, were obtained using a Leica VT1200 vibratome. The obtained slices were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in standard aCSF, saturated with a mixture of 95% O₂ and 5% CO₂.

Subsequently, the slices were transferred to a perfusion chamber and loaded with the fluorescent Ca²⁺-sensitive probe Fluo-4 AM at a final concentration of 5 μM with the addition of 0.02% Pluronic F-127 for 1 hour. To complete the de-esterification of the probe, the slices were washed for 15 minutes in a perfusion system with aCSF saturated with a mixture of 95% O₂ and 5% CO₂.

After loading with the fluorescent probe, the slices were transferred to a specialized chamber for visualization—an RC-26G Open Diamond Bath Imaging Chamber (Warner Instruments)—and placed on the stage of a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). An Achroplan 40x/0.8 W objective was used. The microscope settings for excitation and registration of Fluo-4 fluorescence were as follows: argon laser (488 nm), dichroic mirror HFT 488, emission filter BP 500–550 nm, gain 600–800, offset 0.1. The acquired image series were analyzed using ImageJ software (RRID: SCR_003070).

4.3. Fluorescent [Ca2+]i Measurements

Intracellular calcium dynamics were monitored using the ratiometric indicator Fura-2 AM. Hippocampal cultures were incubated with 2–3 μM of the dye for 40 min at 28–37 °C in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing (in mM): 136 NaCl, 3 KCl, 0.8 MgSO₄, 1.25 KH₂PO₄, 0.35 Na₂HPO₄, 1.4 CaCl₂, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.35. After loading, cells were washed several times with fresh HBSS to remove excess probe. Fluorescence was recorded on an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Leica DMI6000B, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a Hamamatsu CCD camera and an external excitation filter wheel. Sequential illumination at 340 and 387 nm was provided, and emission was collected at 510 ± 40 nm using the FU2 filter set. Time-lapse imaging was performed at 28–30 °C in HBSS. Calcium signals were analyzed by calculating the 340/387 fluorescence ratio from regions of interest drawn over neuronal somata. Background signals obtained from cell-free areas of the field were subtracted before ratio calculation. The resulting traces represent relative changes in intracellular Ca²⁺ concentration.

4.4. Reagents

Domoic acid, NASPM trihydrochloride, ATPA, NBQX, forskolin (Tocris Bioscience, UK), bicuculline (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), L-Glutamic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), NH4Cl (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany), Fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), Neurobasal-A medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), B-27 supplement (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), Trypsin 2.5% (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA).