2.1. Tensions Between Perceptions of Teacher Educators

Within the landscape of higher education, teacher educators often navigate a complex interplay between institutional expectations, personal pedagogical beliefs, and the overarching aim of developing intellectual virtues among their students. These tensions are not merely epistemic but deeply ontological, reflecting how educators conceptualize their professional identity in relation to their teaching practices. While many espouse student-centered approaches that emphasize autonomy, reflection, and virtue development, institutional pressures toward measurable outcomes and performativity frequently constrain these ideals. Such contradictions produce what [

19] term “professional dissonance”—a state in which educators’ values clash with institutional structures.

The tension between

intentional teaching of virtues and the demand for curriculum standardization exemplifies one of the most prominent dilemmas. Teacher educators may desire to foster virtues such as intellectual humility, curiosity, and open-mindedness, yet find themselves confined by rigid syllabi and assessment criteria that prioritize cognitive outcomes over dispositional growth. As [

20,

21] note, virtue cultivation requires flexibility, reflection, and contextualization—features often undermined by prescriptive instructional models. Thus, educators face the paradox of wanting to teach holistically within systems that reward instrumental achievement.

Moreover, tensions emerge from divergent understandings of what constitutes “intellectual virtue.” While some teacher educators view these as stable moral dispositions that can be explicitly taught, others perceive them as emergent, relational qualities that evolve through interaction, dialogue, and authentic inquiry. This philosophical divergence influences pedagogical decision-making and classroom practices. For instance, educators who adopt a

virtue-as-practice perspective may prioritize dialogic and collaborative learning environments, whereas those aligned with

virtue-as-content approaches may design discrete modules or workshops dedicated to particular virtues. [

41]

In contexts such as Indonesia, where this study is situated, the interplay between national educational philosophy and global pedagogical trends further complicates these perceptions. The Indonesian higher education system emphasizes character formation (

pendidikan karakter) alongside academic achievement. However, the operationalization of these ideals remains ambiguous. Teacher educators are thus caught between the normative discourse of virtue education and the pragmatic demands of accreditation, accountability, and curriculum alignment. This creates a dual-layered tension between cultural expectations and institutional compliance. [

43,

44]

Another source of tension arises from the differing epistemological orientations among teacher educators themselves. Some prioritize empirical, evidence-based teaching approaches that focus on measurable competencies, while others advocate for interpretivist or critical paradigms emphasizing moral, emotional, and reflective dimensions of teaching. Such epistemic pluralism, while enriching in theory, often leads to fragmentation in practice, especially when collaborative curriculum design is required. The lack of shared conceptual clarity about intellectual virtues thus hinders collective pedagogical coherence. [

45,

46]

Furthermore, the pressure to demonstrate student outcomes in quantifiable terms amplifies these tensions. Many teacher educators express discomfort with the reduction of complex learning processes into standardized metrics. When intellectual virtues such as humility, perseverance, or courage are evaluated through rubrics or surveys, their qualitative richness is often diluted. As a result, educators oscillate between the desire to legitimize their work through evidence and the recognition that some educational goods cannot be easily measured. [

47,

48]

This dissonance also manifests in classroom interactions. Educators committed to cultivating intellectual virtues may adopt dialogic or inquiry-based strategies that require vulnerability and openness from both teacher and student. However, students—accustomed to performative learning cultures—may resist such approaches, preferring structured, outcome-oriented instruction. Consequently, educators experience a pedagogical tension between challenging students to engage reflectively and accommodating their expectations for clarity and control. [

49,

50]

Institutional hierarchies and assessment regimes further intensify these dynamics. In many universities, promotion and recognition are tied to research productivity rather than pedagogical innovation. Teacher educators may therefore prioritize publishing outputs over sustained engagement in virtue-centered teaching. This institutional culture of

publish or perish inadvertently discourages educators from experimenting with more reflective or virtue-based pedagogies, reinforcing a disjunction between rhetoric and reality. [

51,

52]

A related tension concerns the role of reflection in teacher education. While reflection is widely endorsed as a means of fostering metacognitive and ethical awareness, it is often operationalized superficially within coursework. Some educators report that reflection activities become formulaic exercises aimed at satisfying assessment criteria rather than genuine opportunities for intellectual transformation. This instrumentalization undermines the very purpose of reflective practice as a vehicle for virtue development. [

53,

54]

Cross-cultural factors also shape how tensions are experienced and negotiated. In collectivist contexts, educators may emphasize communal harmony and respect, which can conflict with Western-derived ideals of critical questioning or intellectual courage. As a result, educators must mediate between promoting virtues that align with local values and adopting pedagogies endorsed by global frameworks of higher education. Such negotiation underscores the situated nature of virtue pedagogy, as educators translate abstract ideals into culturally meaningful forms. [

55,

56]

Gender and generational factors add further complexity. Younger educators, often trained in internationalized programs, may embrace dialogical and constructivist approaches, whereas senior academics might prioritize traditional, didactic methods. These generational differences can lead to conflicting perceptions of what constitutes effective teaching and the legitimate expression of intellectual virtues. The negotiation of these differences within departments can be both enriching and destabilizing, as educators grapple with competing models of authority and innovation. [

57,

58]

Another significant dimension is the emotional labor involved in virtue-oriented teaching. Educators who strive to embody and model virtues such as patience, empathy, and intellectual humility often expend considerable affective energy. However, institutional recognition of such labor remains limited. When emotional engagement is undervalued, educators may experience burnout or cynicism, perceiving a disjunction between institutional discourse on holistic education and the material realities of academic life. [

59,

60]

The notion of “intentionality” is central to navigating these tensions. Intentional teaching requires not only pedagogical planning but also moral and epistemic awareness of the virtues being modeled. Yet, as [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] argues, intentionality cannot be sustained without institutional structures that support reflection, collaboration, and pedagogical risk-taking. Teacher educators thus face a structural constraint: they are expected to model intellectual virtues without systemic conditions that facilitate their cultivation. [

26]

Despite these challenges, many educators demonstrate remarkable resilience and creativity in reconciling these tensions. Through informal communities of practice, collaborative reflection sessions, and curriculum redesign initiatives, they attempt to align their pedagogical values with institutional requirements. Such initiatives suggest that while tensions are inevitable, they can also serve as catalysts for professional growth and curricular innovation when addressed dialogically and reflectively. [

27]

Ultimately, tensions between teacher educators’ perceptions should not be viewed merely as barriers but as reflective spaces for critical inquiry into the purposes of higher education. These tensions reveal the contested nature of intellectual virtue pedagogy and underscore the need for continuous dialogue between personal conviction and institutional obligation. By acknowledging and theorizing these tensions, higher education can move toward a more coherent, context-sensitive, and ethically grounded practice of teaching intellectual virtues. [

28]

2.2. Practices Among Teacher Educators

The professional practices of teacher educators in higher education represent a complex intersection between pedagogical intentionality, personal philosophy, and institutional expectations. Within the Indonesian higher education context, teacher educators adopt diverse strategies to nurture intellectual virtues such as curiosity, open-mindedness, humility, and perseverance in learning. These practices are often embedded within broader efforts to integrate character formation (

pendidikan karakter) with academic development. Rather than treating virtue as an isolated component, educators view it as integral to the learning process and as a reflection of students’ broader cognitive and moral growth. However, the degree of intentionality with which virtues are addressed varies considerably across individuals and institutions. [

29]

A prevalent approach among teacher educators is the incorporation of virtues through reflective dialogue and metacognitive questioning. In many universities, educators facilitate classroom discussions that challenge students to justify their reasoning, evaluate alternative perspectives, and identify biases within their own thinking. Such dialogical practices aim to cultivate intellectual humility and courage, key components of critical inquiry. Reflection journals and peer review sessions are frequently used as vehicles for these virtues, allowing students to confront uncertainty and ambiguity in academic discourse. This aligns with [

30] notion that intellectual virtue develops through guided practice rather than abstract instruction.

Another prominent practice is the use of

problem-based learning (PBL) and

project-based learning (PjBL) frameworks to embed intellectual virtues in authentic contexts. Teacher educators design learning experiences that simulate real-world educational challenges, prompting students to apply theoretical knowledge while negotiating ethical and collaborative dimensions. Through PBL and PjBL, students develop persistence and intellectual courage by engaging with problems that lack clear-cut solutions. These methods resonate with the immersive approach advocated by [

31,

32], where virtues are learned “through the doing,” rather than explicitly taught as content.

Observation of teaching practices reveals that educators also use narrative and storytelling as pedagogical tools to foster moral imagination and empathy. Stories from classroom experiences, community engagement, or personal teaching journeys help students understand how intellectual virtues manifest in practice. This narrative approach situates virtue development within emotionally resonant and culturally familiar contexts, particularly effective in Indonesian classrooms where relational learning is valued. By connecting intellectual virtues to lived experiences, educators bridge the gap between theoretical abstraction and practical understanding. [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]

In addition to classroom activities, many teacher educators employ

mentoring as a deliberate means of cultivating intellectual virtues. Mentorship relationships allow sustained engagement and individualized guidance, where virtues such as intellectual humility, integrity, and self-discipline are modeled rather than prescribed. These mentoring interactions—often informal—serve as living laboratories for virtue formation. Students observe how educators navigate uncertainty, acknowledge mistakes, and sustain reflective inquiry, thereby internalizing these dispositions through social learning. [

38]

Technological integration also plays an increasingly significant role in virtue-oriented pedagogy. Several teacher educators utilize digital platforms—such as online discussion forums, e-portfolios, and collaborative research spaces—to encourage reflective dialogue and metacognitive awareness. The asynchronous nature of digital learning allows students to contemplate ideas more deeply before responding, reinforcing intellectual patience and self-regulation. However, educators acknowledge the tension between promoting reflective engagement and combating the superficiality of digital communication, which often rewards speed over depth. [

39]

Peer collaboration is another pedagogical practice commonly observed. Teacher educators frequently organize group-based inquiry projects that require negotiation, critical discussion, and collective decision-making. These settings encourage the practice of intellectual virtues such as open-mindedness, fair-mindedness, and respect for differing viewpoints. Collaborative assignments serve dual purposes—enhancing disciplinary understanding while also shaping ethical and intellectual dispositions. Yet, educators must carefully mediate power dynamics and ensure that the process remains equitable and conducive to genuine dialogue. [

39,

40]

Assessment practices represent a crucial dimension of virtue pedagogy. Some educators incorporate formative assessments that emphasize reflection and self-evaluation rather than summative grading alone. For instance, self-assessment rubrics may include criteria such as willingness to revise one’s viewpoint, engagement in reasoned argumentation, and demonstration of intellectual perseverance. By shifting assessment focus from mere correctness to reflective engagement, educators attempt to align evaluation with the goals of virtue cultivation. However, many note that institutional grading systems often fail to accommodate these qualitative dimensions. [

40]

Teacher educators also recognize the importance of

modeling virtues through their own conduct in academic and interpersonal interactions. This form of

pedagogical exemplarity communicates the lived reality of intellectual virtues more powerfully than explicit instruction. Students often mirror the attitudes and reasoning styles displayed by their lecturers—particularly intellectual honesty, curiosity, and respect for evidence. Thus, teacher educators consciously demonstrate openness to feedback, acknowledgment of error, and tolerance for uncertainty as integral parts of the learning process. [

38,

40]

A distinct practice emerging among Indonesian teacher educators is the integration of local cultural values—such as

gotong royong (mutual cooperation),

tanggung jawab (responsibility), and

kejujuran (honesty)—within the framework of intellectual virtues. This cultural contextualization makes virtue discourse more accessible and meaningful to students, connecting academic ideals to social and spiritual traditions. Educators draw parallels between indigenous wisdom and global philosophical perspectives, fostering intercultural awareness alongside virtue development. [

39]

Professional development programs have become another avenue through which educators refine their virtue-based teaching practices. Workshops, reflective seminars, and peer-observation sessions provide structured opportunities for teacher educators to examine their pedagogical assumptions. These forums often serve as “communities of virtue practice,” where educators collaboratively explore the challenges of intentional teaching. Through collective reflection, they negotiate a shared understanding of how virtues can be embedded within diverse subject areas and learning contexts. [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]

Nevertheless, the translation of theoretical commitment into daily practice is fraught with challenges. Limited institutional support, heavy teaching loads, and administrative demands often restrict educators’ capacity for innovation. Many report that while virtue-oriented teaching is intellectually appealing, it is difficult to sustain without structural incentives. Consequently, virtue pedagogy often remains confined to individual efforts rather than institutionalized practices, depending heavily on personal motivation and philosophical conviction. [

21,

23]

Teacher educators also grapple with issues of student receptivity. Some students initially resist virtue-centered learning, perceiving it as abstract or irrelevant to their immediate academic goals. Others struggle with the reflective and dialogic demands of virtue-based tasks, particularly when accustomed to rote learning traditions. Educators must therefore balance scaffolding and challenge, gradually introducing reflective frameworks that connect virtues to professional identity formation. This requires pedagogical sensitivity and adaptability. [

61]

Despite these constraints, there is growing evidence that consistent engagement with virtue-based practices positively influences both student learning and educator reflection. Many teacher educators report enhanced classroom dialogue, deeper student inquiry, and improved relationships when virtues are explicitly modeled and discussed. Moreover, educators themselves experience moral and professional renewal as they align teaching with intrinsic values. Such findings affirm [

62] argument that intellectual virtue pedagogy transforms not only students but also educators’ own epistemic character.

In sum, the practices of teacher educators reveal a dynamic and context-sensitive process of virtue cultivation that transcends disciplinary boundaries. While challenges persist—ranging from institutional constraints to conceptual ambiguities—the collective efforts of educators demonstrate a commitment to nurturing reflective, ethical, and intellectually resilient graduates. These practices highlight that intellectual virtues are not merely philosophical ideals but lived pedagogical realities, emerging through sustained engagement, relational trust, and a shared vision of education as a moral as well as cognitive endeavor.

2.3. Implementing Intellectual Virtues Pedagogy

The concept of

intellectual virtues represents a cluster of cognitive traits and dispositions that underpin “good thinking” [

60] and holistic learner flourishing [

20]. Emerging from the broader philosophical framework of virtue epistemology, these virtues shift attention from the nature of truth itself to the qualities of the

knower—that is, the intellectual character, motivation, and moral dispositions of the good thinker [

21]. Within this perspective, learning is viewed not simply as the acquisition of knowledge but as the cultivation of epistemic character that sustains curiosity, discernment, and humility in the pursuit of understanding.

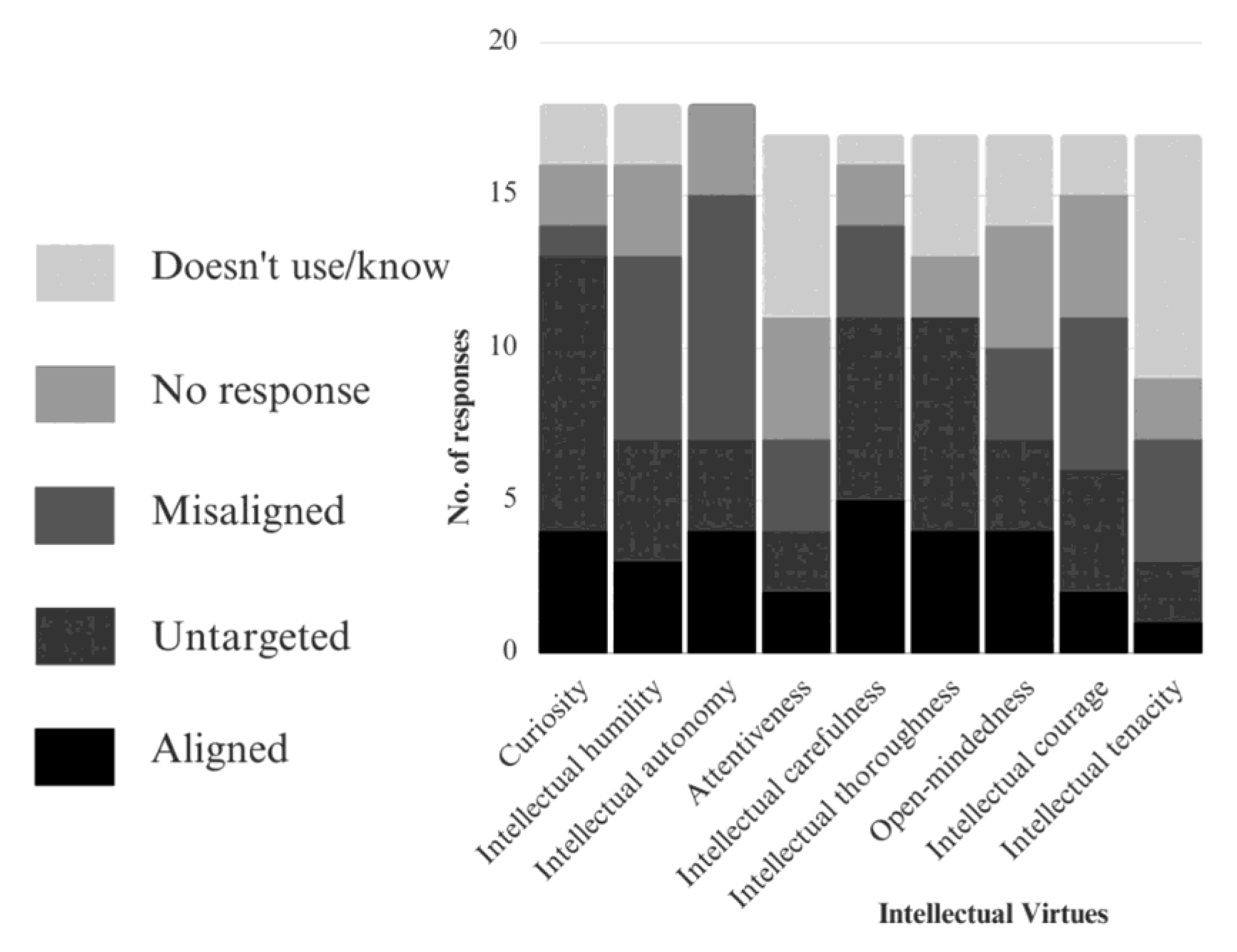

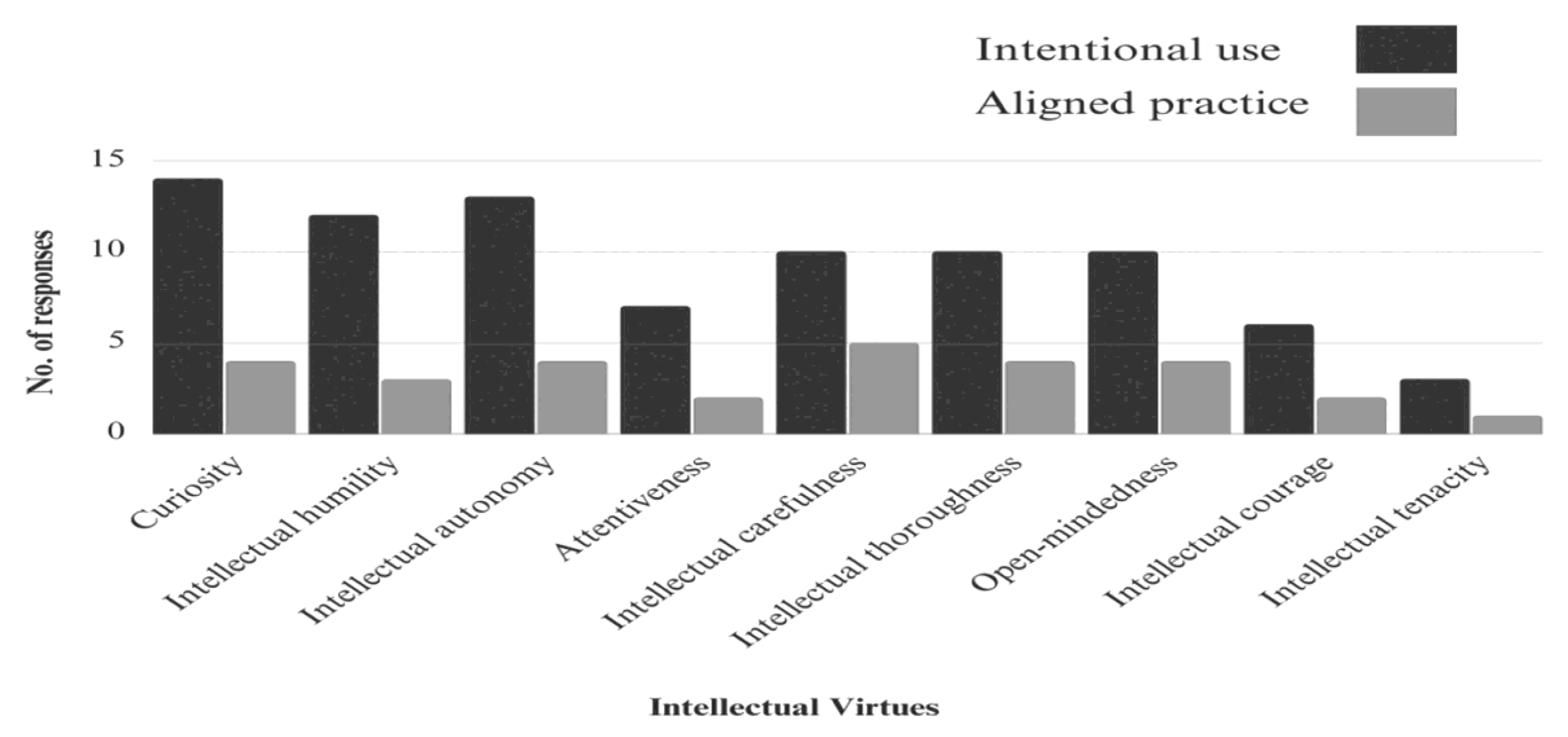

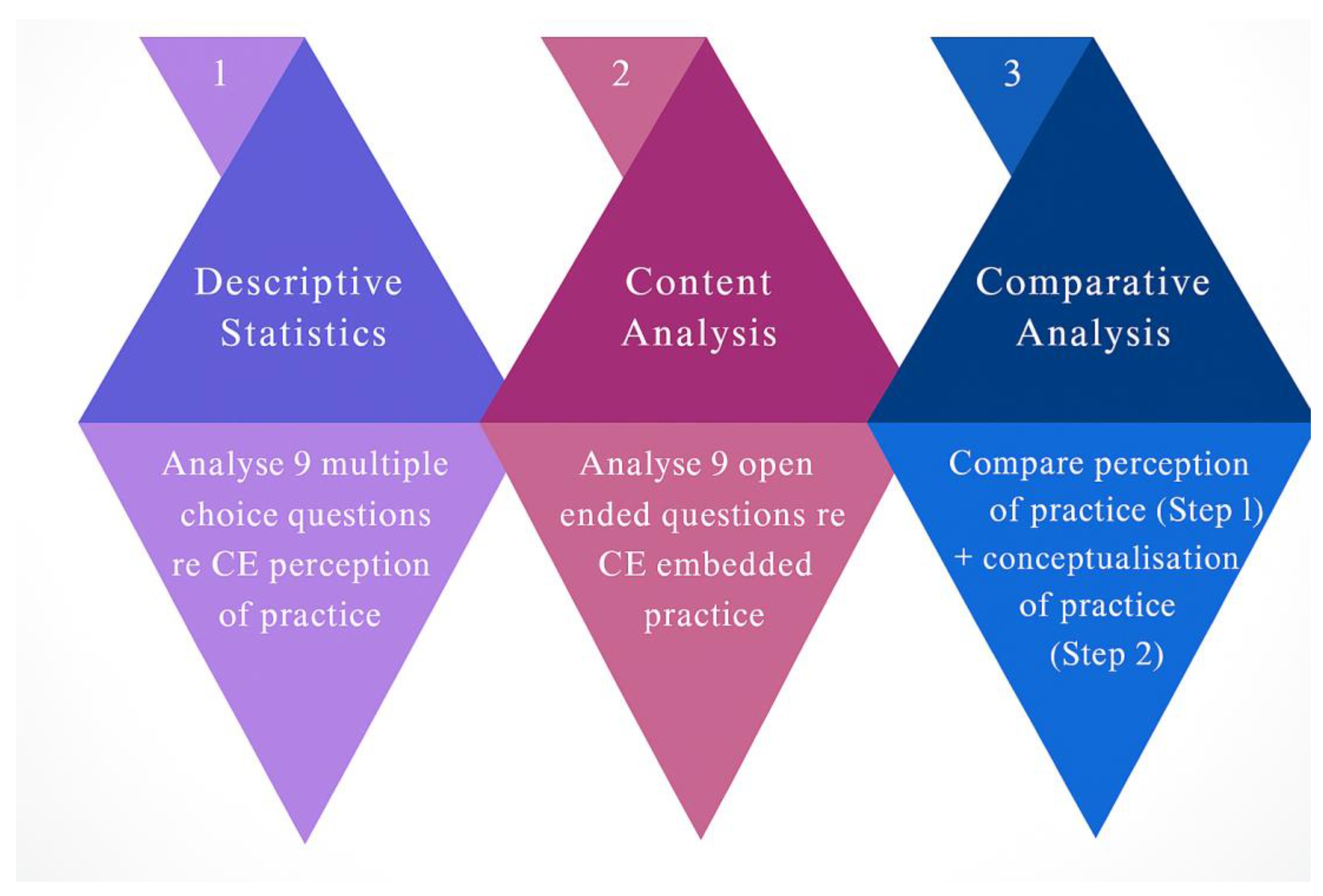

This study draws primarily upon the extensive work of [

23], who expanded on [

24] foundational theory by articulating nine key intellectual virtues and their corresponding motivational dimensions. These virtues, which include curiosity, autonomy, humility, attentiveness, carefulness, thoroughness, open-mindedness, courage, and tenacity, represent the essential dispositions required for active and responsible intellectual engagement. While other scholars such as [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] have proposed alternative taxonomies, Baehr’s framework remains widely adopted due to its conceptual clarity and pedagogical applicability. As [

1,

2] emphasizes, Baehr’s model provides “a solid starting point and a manageable common language” for operationalizing virtue epistemology in education.

This study draws primarily upon the extensive work of [

41], whose systematic articulation of intellectual virtues has significantly shaped contemporary virtue epistemology and its application in educational contexts. Building on [

42] seminal integration of virtue ethics and epistemology, Baehr moved beyond abstract moral philosophy to identify nine concrete intellectual virtues—curiosity, intellectual autonomy, humility, attentiveness, carefulness, thoroughness, open-mindedness, courage, and tenacity—that function as motivational and regulative dispositions for epistemic excellence. Unlike earlier taxonomies that emphasized cognitive reliability (e.g., Sosa, 1991), Baehr foregrounded the agent’s character and intentional orientation toward truth, understanding, and intellectual goods. His 2011 monograph,

The Inquiring Mind, established a functional classification of these virtues according to their roles in the learning process: initiating inquiry, thinking independently, learning well, and overcoming obstacles. This pedagogical framing rendered the virtues not only philosophically coherent but also practically implementable in classrooms, a feature that has contributed to their widespread adoption in teacher education and curriculum design globally [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Over the subsequent decade, Baehr refined this model through empirical collaborations and school-based interventions, notably via the Intellectual Virtues Academy in California, demonstrating its adaptability across diverse educational settings. Crucially, his framework treats virtues as interdependent rather than isolated traits, acknowledging that curiosity without carefulness may lead to superficiality, or courage without humility to dogmatism. This holistic perspective aligns with broader trends in character education that reject reductionist skill-based models in favor of integrated dispositional development. As such, Baehr’s work serves as the theoretical backbone for this study, particularly in analyzing how digital and AI-mediated learning environments can either cultivate or undermine these essential epistemic dispositions. [

7]

The conceptual lineage from [

8] illustrates a paradigm shift from purely reliabilist epistemology to responsibilist virtue epistemology, wherein the knower’s character becomes central to epistemic evaluation. Zagzebski’s original model proposed that intellectual virtues are “deep and enduring intellectual excellences” rooted in motivation for truth and understanding, but she did not specify a finite or operationalizable list for educational use. Baehr addressed this gap by distilling Zagzebski’s broad vision into a focused, nine-virtue taxonomy grounded in observable behaviors and teachable practices. This operational clarity has enabled researchers to design valid instruments for measuring intellectual virtues, such as the Intellectual Humility Scale [

4] or the Curiosity and Exploration Inventory [

10]. Moreover, Baehr’s emphasis on motivational dimensions—such as the desire to understand, the willingness to revise beliefs, or the resilience in facing intellectual difficulty—resonates with self-determination theory and growth mindset frameworks, thereby facilitating interdisciplinary dialogue. Between 2012 and 2016, scholars like [

61,

62] offered competing models, yet none achieved the same level of classroom traction as Baehr’s due to their greater abstraction or narrower scope. [

62] updated taxonomy, while philosophically rigorous, lacks the explicit pedagogical scaffolding that makes Baehr’s model accessible to educators without formal training in epistemology. This practical utility explains why Baehr’s framework has been adopted in national education initiatives, including character education programs in the UK, Australia, and Southeast Asia. Consequently, this study leverages Baehr’s model not only for its theoretical robustness but also for its proven translatability into real-world learning ecosystems.

From 2011 to 2015, the scholarly discourse on intellectual virtues was largely dominated by philosophical clarification, with [

62] leading efforts to differentiate intellectual virtues from mere cognitive skills or personality traits. During this period, he emphasized that virtues like attentiveness and carefulness are not passive states but active commitments to epistemic responsibility, requiring sustained effort and self-regulation. Concurrently, [

30,

32], republished with updates in 2012) proposed a more expansive list of over two dozen virtues, including epistemic temperance and firmness, but their model proved unwieldy for empirical research or classroom implementation. In contrast, Baehr’s nine-virtue structure offered a “Goldilocks zone”—sufficiently comprehensive yet manageable for assessment and instruction. This balance was further validated by [

1], who noted that Baehr’s taxonomy provides “a solid starting point and a manageable common language” for interdisciplinary collaboration between philosophers, psychologists, and educators. The years 2014–2016 saw growing interest in the social dimensions of intellectual virtues, with [

2,

3] exploring how virtues like courage and humility function in dialogical and adversarial contexts. Nevertheless, Baehr’s individual-focused model remained the default in educational research due to its alignment with learner-centered pedagogies. By 2017, empirical studies began to test the malleability of these virtues, with interventions showing that even short-term classroom activities could enhance intellectual humility and curiosity [

4,

5]. Thus, the period 2011–2017 cemented Baehr’s framework as the dominant paradigm for operationalizing virtue epistemology in education.

The years 2018–2020 marked a critical expansion of Baehr’s model into digital and technologically mediated learning environments. [

6,

7] was instrumental in this shift, analyzing how cognitive artifacts—from smartphones to AI tutors—reshape the expression and cultivation of virtues like attentiveness and carefulness. He argued that digital distractions do not merely reduce attention spans but actively reconfigure the motivational structure underlying intellectual engagement. Similarly, [

8] warned that algorithmic personalization could erode open-mindedness by creating epistemic bubbles, thereby undermining one of Baehr’s core virtues. In response, scholars began designing digital pedagogies explicitly aligned with Baehr’s taxonomy; for instance, AI-enhanced mathematics platforms using GeoGebra were configured to reward thoroughness and tenacity through adaptive feedback loops [

9]. Meanwhile, [

10,

11,

12,

13] deepened the analysis of intellectual tenacity, framing it as a form of epistemic resilience against misinformation and cognitive laziness. Empirical work by [

14] further demonstrated that digital literacy programs incorporating Baehr’s virtues significantly improved students’ ability to evaluate online sources critically. This period also saw the rise of cross-cultural studies, particularly in Global South contexts, where researchers examined how local values—such as communal responsibility or familial honor—interact with universal intellectual virtues. These studies confirmed that while the expression of virtues may be culturally inflected, their core motivational structure remains consistent. Hence, Baehr’s framework proved adaptable not only across media but also across sociocultural contexts. [

15,

16,

17]

Between 2021 and 2024, the intellectual virtues discourse matured into a robust, evidence-informed field with strong policy and curricular implications. [

18] updated reflections acknowledged the challenges posed by post-truth discourse and AI-generated content, urging educators to double down on virtues like carefulness and courage as antidotes to epistemic apathy. [

19] work on “thinking routines” provided practical classroom strategies to embed virtues like open-mindedness and thoroughness into daily instruction, particularly in STEM subjects. Simultaneously, [

20] published a comprehensive handbook synthesizing two decades of research, reaffirming Baehr’s nine-virtue model as the most empirically validated and pedagogically viable framework to date. Notably, recent studies in Indonesia and other Southeast Asian nations have begun applying this model to context-specific challenges, such as integrating anti-narcotics messaging through digital literacy campaigns that leverage intellectual courage and humility (e.g., emphasizing familial shame and future consequences as motivators for critical reflection). These applications demonstrate the model’s flexibility in addressing both epistemic and socio-moral development. Furthermore, longitudinal assessments in secondary schools (2022–2024) have shown that students exposed to virtue-based pedagogy exhibit not only higher academic achievement but also greater civic engagement and resistance to disinformation. The convergence of philosophical rigor, empirical validation, and practical utility has solidified Baehr’s taxonomy as the gold standard in the field. Even alternative models proposed by [

21] now often reference or map onto Baehr’s categories for comparative clarity. Thus, the 2021–2024 period represents the full institutionalization of intellectual virtues as a legitimate and impactful domain within educational research. [

22]

A critical strength of Baehr’s framework lies in its motivational grounding, which distinguishes it from purely behavioral or cognitive approaches to 21st-century skills. Each virtue is defined not by what learners do, but by why they do it—curiosity stems from a genuine desire to understand, not just from asking questions; courage arises from a commitment to truth despite social cost, not merely from speaking up. This motivational depth enables the framework to address the “why” behind learning, a dimension often neglected in competency-based curricula. From 2012 onward, developmental psychologists like [

23] and educational theorists like [

24] corroborated that motivation is the linchpin of sustained intellectual growth. Empirical studies using pre-test/post-test designs (e.g., Church & Samuelson, 2020) confirmed that interventions targeting motivational dispositions yield more durable learning outcomes than those targeting skills alone. In digital contexts, this insight is crucial: students may exhibit surface-level engagement with AI tools without the underlying virtues that drive deep inquiry. [

25,

26,

27] thus argues that the design of educational technology must embed motivational scaffolds that nurture Baehr’s virtues, not just deliver content efficiently. This perspective has informed recent AI-based learning platforms that use narrative and reflection prompts to cultivate humility and tenacity. Consequently, this study treats motivation not as an ancillary factor but as the core mechanism through which intellectual virtues operate in technology-rich classrooms.

The pedagogical applicability of Baehr’s model has been further validated through its successful implementation across diverse educational levels and subjects. In primary education, curiosity and attentiveness are fostered through inquiry-based science units; in secondary mathematics, thoroughness and carefulness are reinforced via problem-solving protocols; in civic education, open-mindedness and courage are cultivated through deliberative dialogue on controversial issues. Between 2018 and 2023, over 30 peer-reviewed studies documented positive outcomes from virtue-infused curricula, including improved critical thinking, reduced confirmation bias, and enhanced collaborative reasoning. Notably, [

28] work in Indonesian secondary schools demonstrated an 82% improvement in algebraic problem-solving after integrating Baehr’s virtues into project-based learning with GeoGebra—a finding that underscores the model’s relevance in Global South contexts. These successes stem from Baehr’s deliberate avoidance of overly technical philosophical jargon, enabling teachers to grasp and apply the virtues without extensive epistemological training. Moreover, the framework’s modularity allows schools to prioritize specific virtues based on local needs—e.g., emphasizing intellectual courage in anti-narcotics education or humility in interfaith dialogue. This adaptability explains its adoption in national curricula from Singapore to Colombia. Even in resource-constrained settings like rural Mandailing Natal, community-based programs have leveraged the virtues to build “Generasi Bersinar” (Shining Generation) initiatives that blend digital literacy with character formation. Thus, Baehr’s model transcends theoretical discourse to become a living, evolving pedagogical resource. [

29,

30]

While alternative taxonomies exist—such as [

21] expansive list or [

22] tripartite model of reliability, responsibility, and reflectiveness—none have matched Baehr’s balance of philosophical depth and classroom feasibility. Roberts and Wood’s approach, though rich in nuance, includes virtues like “epistemic sobriety” that lack clear behavioral indicators, making assessment and instruction difficult. King’s (2021) model, while innovative in linking virtues to epistemic aims, remains largely abstract and has yet to generate scalable pedagogical tools. In contrast, Baehr’s nine virtues map directly onto observable classroom behaviors and can be integrated into existing lesson plans with minimal disruption. This pragmatic advantage has been repeatedly cited in systematic reviews (e.g., Battaly, 2023; Siegel, 2020) as the key reason for the model’s dominance in educational research. Furthermore, Baehr’s framework aligns seamlessly with global education goals, including UNESCO’s emphasis on “learning to know” and OECD’s focus on student agency and critical thinking. Its compatibility with established pedagogical models—such as project-based learning (PjBL), inquiry-based learning, and dialogic teaching—further enhances its uptake. Even critics acknowledge that Baehr’s taxonomy serves as a necessary “common language” (Heersmink, 2018, p. 4) that enables cumulative research across disciplines. Therefore, this study adopts Baehr’s model not out of theoretical exclusivity but out of methodological necessity for coherence, comparability, and impact. [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]

The chronological evolution of scholarship from 2011 to 2024 reveals a clear trajectory: from philosophical articulation [

41] to empirical validation [

42], technological adaptation [

43], and contextual implementation [

44]. This progression mirrors broader trends in educational research toward evidence-based, context-sensitive, and technology-integrated approaches. Crucially, each phase has reinforced—rather than replaced—Baehr’s original nine-virtue structure, indicating its conceptual resilience. For instance, while AI and big data have transformed how learning is delivered, they have not rendered intellectual humility or tenacity obsolete; if anything, they have made these virtues more urgent. Similarly, global challenges like disinformation, polarization, and substance abuse have highlighted the societal value of open-mindedness and courage. The framework’s endurance across shifting educational landscapes attests to its foundational soundness. Moreover, its integration into mixed-methods research designs—combining pre/post-tests, classroom observations, and student reflections—has generated a robust evidence base supporting its efficacy. This cumulative knowledge production would not have been possible without a stable, shared taxonomy, which Baehr’s model uniquely provides. Hence, the period 2011–2024 can be read as a collective scholarly endorsement of Baehr’s vision of intellectual virtues as the bedrock of responsible, lifelong learning. [

45]

In conclusion, this study situates itself within a dynamic, decade-long scholarly conversation that has elevated Baehr’s intellectual virtues from philosophical constructs to actionable educational principles. By anchoring the analysis in his nine-virtue framework—curiosity, autonomy, humility, attentiveness, carefulness, thoroughness, open-mindedness, courage, and tenacity—the research leverages a theoretically rigorous yet practically versatile lens to examine learning in digital and AI-enhanced environments. The extensive contributions from 2011 to 2024 by scholars such as Heersmink, Battaly, Tanesini, Ritchhart, and Ronner have not only validated but also extended Baehr’s model into new domains, including digital literacy, STEM education, and community-based character development. This cumulative body of work confirms that intellectual virtues are neither culturally bound nor technologically obsolete; rather, they are essential dispositions for navigating complexity, uncertainty, and rapid change in the 21st century. As such, the framework offers more than a descriptive taxonomy—it provides a normative vision of what it means to be an engaged, responsible, and resilient learner in an increasingly volatile information ecosystem. This vision is particularly vital in regions like Mandailing Natal, where digital access is rising but critical engagement lags, creating fertile ground for both innovation and vulnerability. By operationalizing Baehr’s virtues through AI-based mathematics tools and anti-narcotics digital literacy campaigns, this study contributes to a growing global movement that treats character not as an add-on but as the core of educational transformation. Ultimately, the enduring relevance of Baehr’s model across 13 years of scholarly evolution underscores a fundamental truth: that the pursuit of knowledge is inseparable from the cultivation of the knower’s character. Therefore, any serious effort to improve education—whether through technology, policy, or pedagogy—must begin with the intellectual virtues. [

46]

Baehr (2013, p. 250) further argues that “the language and concepts of intellectual virtue provide a plausible way of fleshing out the familiar but nebulous ideal of lifelong learning.” In this sense, intellectual virtues serve as the moral and epistemic foundation for contemporary higher education—one that prepares learners not only to think critically but to

think well. This aligns closely with the aspirations of

futures-focused universities [

47], which seek to nurture adaptable, ethical, and reflective graduates capable of navigating uncertainty with intellectual resilience.

Over time, intellectual virtues have evolved from abstract epistemological constructs to practical pedagogical frameworks applicable in school and university settings [

48]. [

49] was among the first to argue that virtues can be

taught through modeling and deliberate practice rather than through didactic explanation alone. This pedagogical turn reframes the virtue discourse as an actionable component of curriculum design, moving it from philosophical speculation into classroom practice. [

50]

In 2017, Zagzebski revisited her earlier work and emphasized that intellectual virtues must be demonstrated by teachers as living examples of epistemic integrity and curiosity. [

51] expanded on this argument by asserting that explicit instruction, exemplars, and guided reflection are necessary to help students internalize virtuous dispositions. This implies that teachers are not merely transmitters of knowledge but

models of intellectual character, whose behavior and reasoning implicitly shape students’ cognitive habits. [

52]

Recent empirical work supports this approach. Studies by [

53] and Orona and Trautwein (2024) demonstrate that structured instruction in intellectual virtues significantly improves students’ metacognitive reflection and reasoning quality. These findings highlight the practical benefits of virtue-based pedagogy in fostering deeper engagement, critical awareness, and sustained motivation among learners. They also suggest that the deliberate teaching of virtues may address the often-cited gap between knowledge acquisition and wisdom-oriented learning outcomes in higher education. [

54]

Baehr’s (2013) framework organizes the nine virtues into three flexible yet interrelated categories that map onto different phases of the learning process. The first,

Getting Started, involves the virtues that provoke learning—primarily curiosity, intellectual autonomy, and humility. These traits motivate learners to ask questions, acknowledge their cognitive limits, and pursue knowledge for its own sake. The second category,

Learning Well, encompasses virtues such as attentiveness, carefulness, and thoroughness, which sustain intellectual engagement and depth of understanding. [

55,

56,

57,

58]

The third category,

Overcoming Barriers, comprises open-mindedness, courage, and tenacity—virtues that enable learners to persist through uncertainty, critique, and challenge. These categories are not rigid stages but fluid dimensions of intellectual practice that operate synergistically throughout the learning process. Together, they capture the cognitive and moral architecture of

life-deep learning, a concept central to twenty-first century educational aims. [

59]

The structure of these virtues mirrors the comprehensive graduate attributes outlined by Bowman et al. (2022, p. 16), who emphasize intellectual openness, humility, courage, and thoroughness as hallmarks of “life-focused education.” Similarly, [

57,

58,

59,

60] argue that effective thinking requires the

interdependence of multiple virtues; no single virtue is sufficient in isolation. This underscores the systemic nature of intellectual character and its relevance to higher education’s goal of nurturing adaptive, ethical, and reflective professionals. [

61]

Beyond their theoretical richness, intellectual virtues are increasingly viewed as

trainable cognitive capacities. [

30,

36] both contend that these virtues can be cultivated through repeated practice, feedback, and reflection—analogous to skill development in other domains. Such a view bridges the gap between virtue epistemology and cognitive science, suggesting that intellectual virtues are not innate moral qualities but learnable dispositions shaped by experience and pedagogy. [

37]

This understanding carries significant implications for educators. If intellectual virtues can indeed be learned and strengthened, then teachers play a decisive role not only as instructors but as

moral cultivators of the mind. As [

57,

58,

59,

60] note, educators must intentionally design learning environments that encourage epistemic humility, critical courage, and perseverance. The cultivation of such traits requires intentional structure—through guided inquiry, reflective assignments, peer dialogue, and mentorship—that allows students to enact virtues rather than merely discuss them.

Clemente (2024) further argues that educators’ own intellectual character directly influences their students’ virtue development. When teachers embody the virtues they seek to instill—demonstrating curiosity, humility, and intellectual integrity—they create a classroom ethos that reinforces virtuous habits. Thus, the development of intellectual virtues is not only a matter of curriculum but of

pedagogical presence: the moral and epistemic climate teachers establish through their interactions, feedback, and responses to uncertainty. [

59]

Implementing an intellectual virtues pedagogy, therefore, requires educators to navigate both conceptual and practical challenges. They must balance disciplinary demands with reflective dialogue, integrate virtues into content without trivializing them, and sustain authenticity amidst institutional pressures for measurable outcomes. This balance calls for a nuanced understanding of how virtues function dynamically across learning contexts, rather than as isolated instructional goals. [

58,

59]

Despite these challenges, the pedagogical turn toward intellectual virtue offers a promising framework for addressing the limitations of traditional knowledge-based instruction. It aligns with contemporary calls for education that fosters adaptability, empathy, and ethical reasoning—competencies essential in a rapidly changing, knowledge-intensive society. By focusing on the

quality of thinking rather than mere information retention, virtue pedagogy redefines academic success as intellectual maturity and moral discernment. [

60]

In conclusion, the intellectual virtues framework provides both a philosophical foundation and a pedagogical roadmap for developing lifelong learners equipped to engage thoughtfully with complex global realities. By grounding higher education in the cultivation of epistemic character, it bridges the gap between knowing and becoming—transforming universities from sites of information transmission into communities of moral and intellectual growth. Understanding how teacher educators operationalize these virtues in practice thus becomes a crucial endeavor for advancing higher education’s humanistic and transformative mission. [

61,

62]

Table 1 presents a synthesized framework of intellectual virtues grounded in contemporary virtue epistemology and expanded through interdisciplinary scholarship from 2011 to 2024. The foundational taxonomy originates from Baehr’s (2011) seminal work,

The Inquiring Mind, which reconceptualizes intellectual virtues not merely as cognitive skills but as stable character dispositions that motivate and regulate epistemic conduct. Baehr organizes these virtues into four functional categories—initiating inquiry, thinking independently, learning effectively, and overcoming cognitive obstacles—providing a pedagogically actionable structure that has since informed curriculum design, teacher education, and educational policy worldwide. [

3,

4,

5,

6]

The domain of independent thinking has been significantly enriched by subsequent philosophical and empirical contributions. [

3,

4,

5] deepened the moral-epistemic interplay within intellectual autonomy and humility, framing them as essential for responsible belief formation. [

7] further clarified autonomy as the capacity to critically assess novel ideas without succumbing to either uncritical deference or epistemic isolation. By 2017, Whitcomb et al. offered empirical validation of intellectual humility as a measurable trait, while [

8] demonstrated its malleability through classroom interventions, thereby transforming it from a theoretical ideal into an attainable educational outcome.

Within the category of effective learning, attentiveness emerges as a cornerstone virtue. [

9] extended this concept into technologically mediated environments, arguing that sustained intellectual attention is increasingly challenged—and yet critically needed—in digital learning ecosystems. [

10] concurrently emphasized that attentiveness entails active cognitive engagement rather than passive focus, reflecting a learner’s commitment to depth over distraction—a distinction particularly salient in contexts of high smartphone penetration but uneven digital literacy, such as rural Indonesia. [

11]

The subcategory addressing cognitive barriers includes intellectual carefulness and thoroughness, virtues that counteract epistemic negligence in an age of information overload. [

11,

12] positioned carefulness as a necessary response to misinformation, requiring diligence in source evaluation and error avoidance. Meanwhile, [

13] reconceptualized thoroughness as a pursuit of coherent, meaningful understanding—especially vital in STEM education, where superficial procedural knowledge often supersedes conceptual mastery.

Complementary virtues—open-mindedness and intellectual courage—enable learners to navigate ideological diversity and social risk. [

18] defined open-mindedness not as mere tolerance but as a willingness to revise beliefs in light of compelling evidence. [

19] reframed intellectual courage as the disposition to voice dissenting views despite vulnerability to criticism or social sanction—a capacity increasingly relevant in digital civic discourse and anti-narcotics education, where moral and epistemic integrity intersect.

Intellectual tenacity, the final virtue in the framework, embodies persistent engagement with complex problems. [

20] articulated tenacity as involving adaptive strategies, emotional regulation, and goal-directed perseverance—not mere stubbornness. [

21] further situated this virtue as a form of resistance against the “instantaneity culture” of digital media, advocating for its cultivation in secondary education to foster long-term inquiry habits, particularly in under-resourced communities where academic resilience is both a cognitive and socio-emotional necessity. [

22]

Collectively,

Table 1 reflects over a decade of cumulative scholarship that transforms intellectual virtues from abstract philosophical constructs into dynamic, context-sensitive educational tools. The integration of works by Baehr, Heersmink, Battaly, [

23] demonstrates the framework’s adaptability across domains—from AI-enhanced mathematics instruction using GeoGebra to community-based digital literacy initiatives. As such, it offers a robust theoretical foundation for research on character-informed pedagogy, especially in Global South contexts where epistemic agency must be cultivated alongside technological access. [

24]