Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Blanching Treatments

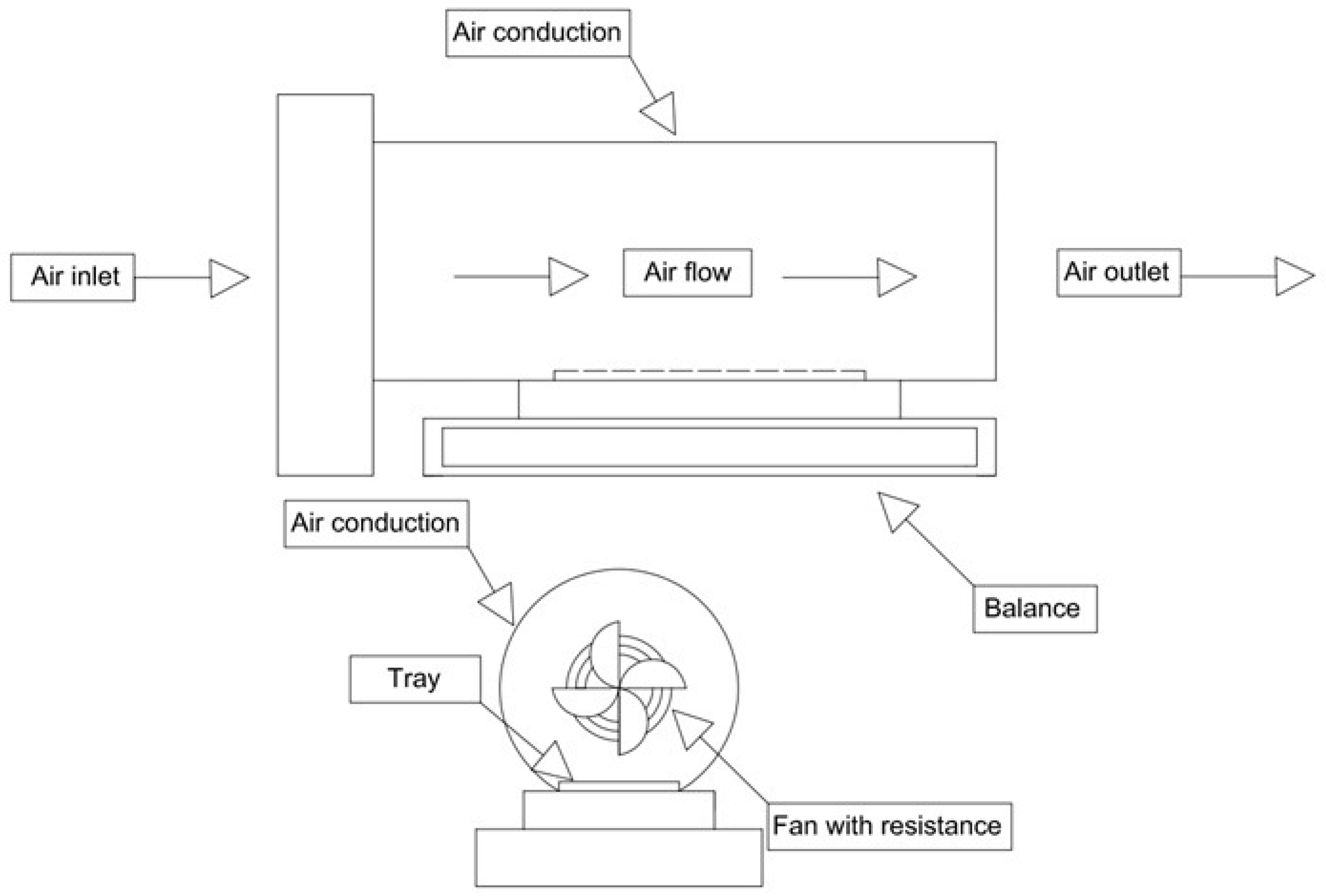

2.3. Drying Treatments

2.4. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity Analyses

2.5. Inulin Analysis

2.6. Color

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

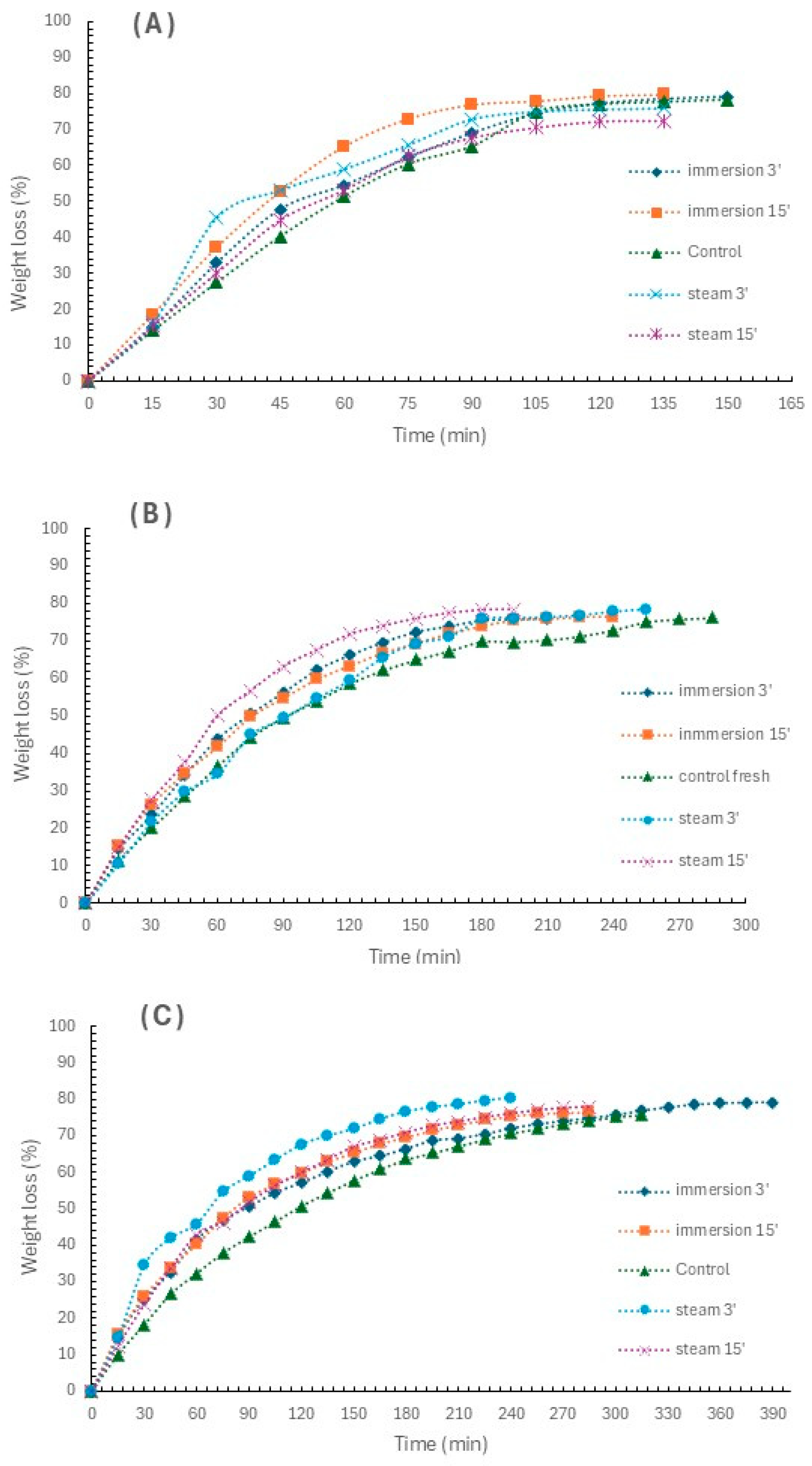

3.1. Drying Kinetics

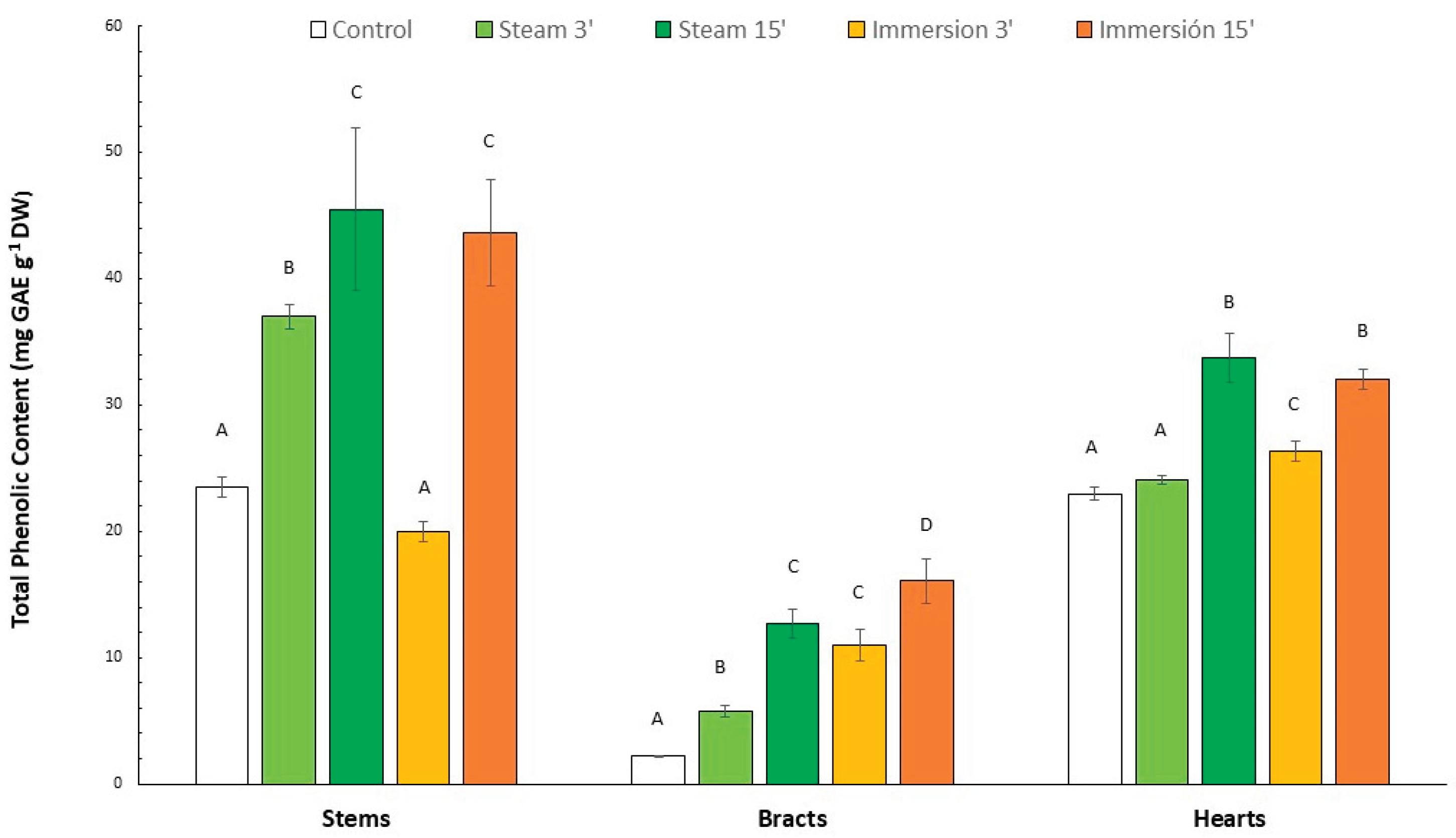

3.2. Total Phenolic Content

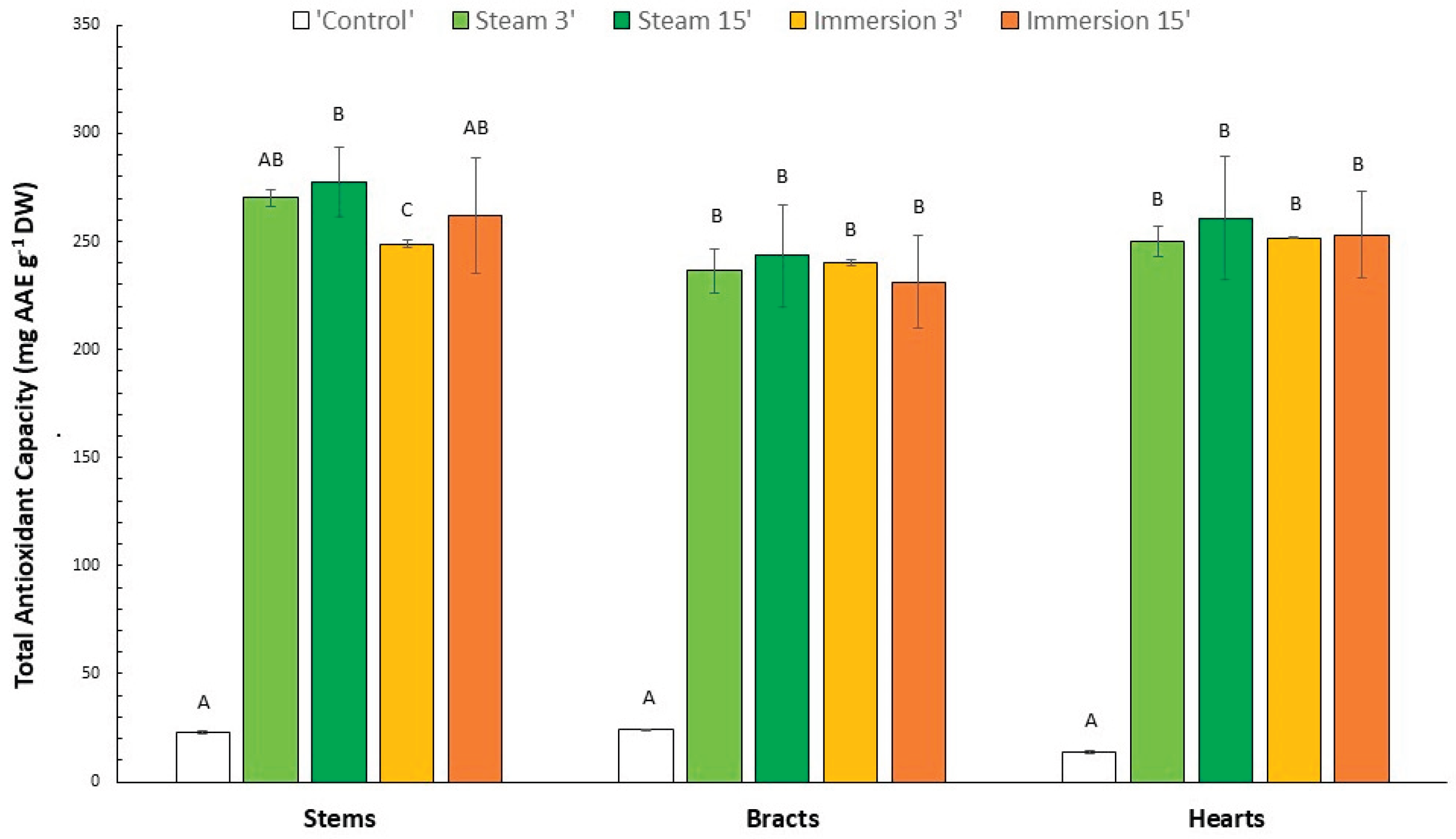

3.3. Total Antioxidant Capacity

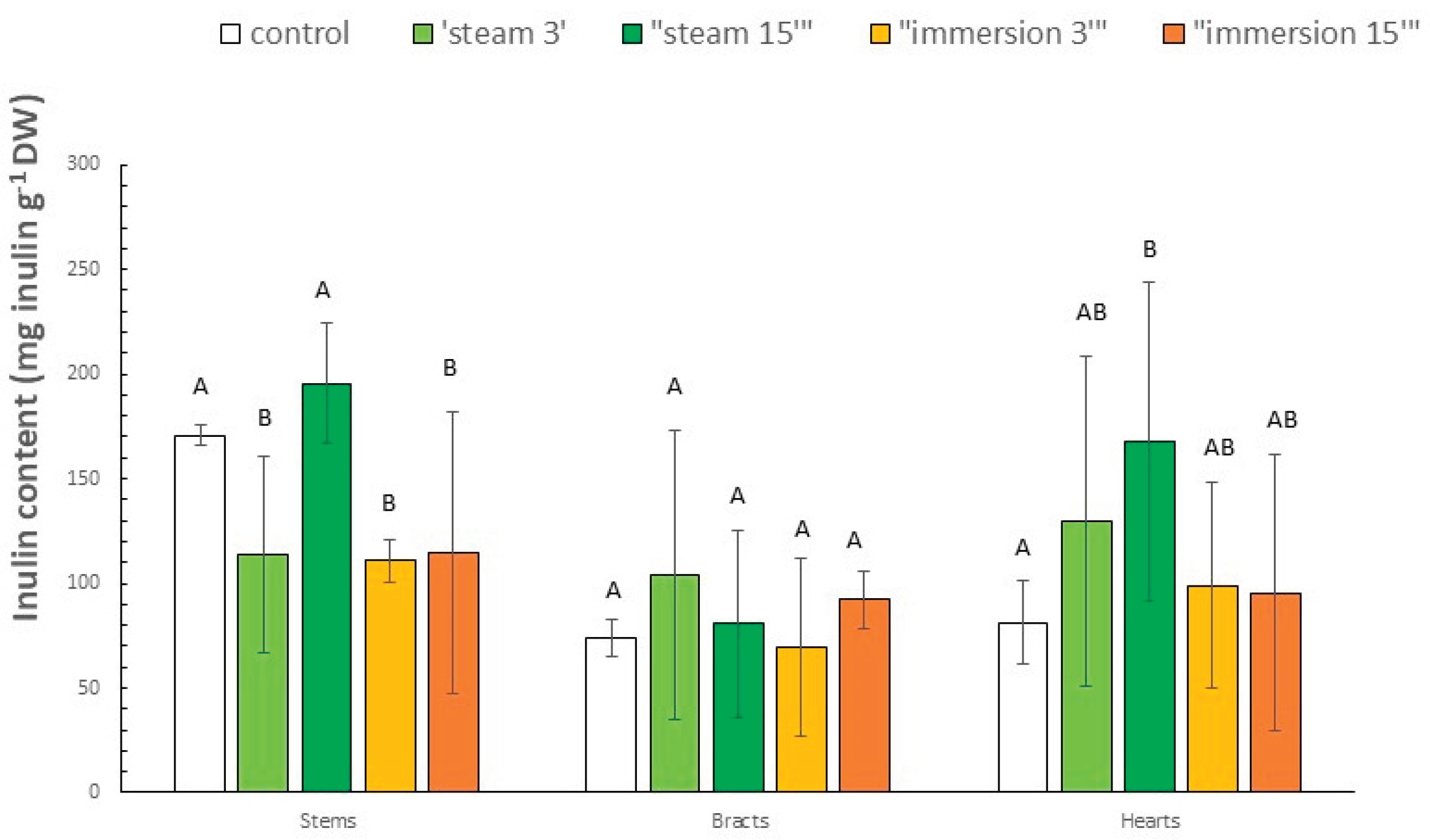

3.4. Inulin

3.5. Color

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPC | Total Phenolic Content |

| TAC | Total Antioxidant Capacity |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| BI | Browning Index |

| TCD | Total Color Difference |

| DW | Dry Weight |

| FW | Fresh Weight |

| GAE | Galic Acid Equivalents |

| AAE | Ascorbic Acid Equivalents |

References

- Pandino, G.; Lombardo, S.; Mauromicale, G.; Williamson, G. Profile of polyphenols and phenolic acids in bracts and receptacles of globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus) germplasm. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24(2), 148–153. [CrossRef]

- Tortosa-Díaz, L.; Saura-Martínez, J.; Taboada-Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G. B.; López-Gómez, A.; Marín-Iniesta, F. Influence of industrial processing of artichoke and by-products on the bioactive and nutritional compounds. Food Eng. Rev. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sedlar, T.; Čakarević, J.; Tomić, J.; Popović, L. Vegetable by-products as new sources of functional proteins. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2021, 76(1), 31–36. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, K.; Cătoi, A. F.; Vodnar, D. C. Bioactive compounds extracted from tomato processing by-products as a source of valuable nutrients. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2018, 73(4), 268–277. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Barbhai, M. D.; Hasan, M.; Dhumal, S.; Singh, S.; Pandiselvam, R.; Rais, N.; Natta, S.; Senapathy, M.; Sinha, N.; Amarowicz, R. Onion (Allium cepa L.) peel: A review on the extraction of bioactive compounds, its antioxidant potential, and its application as a functional food ingredient. J. Food. Sci. 2022, 87(10), 4289–4311. [CrossRef]

- Quispe, M. A.; Valenzuela, J. A. P.; de la Cruz, A. R. H.; Silva, C. R. E.; Quiñonez, G. H.; Cervantes, G. M. M. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols From Globe Artichoke (Cynara Scolymus L.) Bracts Residues Using Response Surface Methodology. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2021, 20(3), 277–290. [CrossRef]

- Benkhoud, H.; Baâti, T.; Njim, L.; Selmi, S.; & Hosni, K. Antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antihyperlipidemic activities of wheat flour-based chips incorporated with omega-3-rich fish oil and artichoke powder. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45(3), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Lopes da Silva, J. A.; Pintado, M. Fruit and vegetable by-products’ flours as ingredients: A review on production process, health benefits and technological functionalities. Lwt. 2022, 154 (June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Sergio, L.; Gatto, M. A.; Spremulli, L.; Pieralice, M.; Linsalata, V.; Di Venere, D. Packaging and storage conditions to extend the shelf life of semi-dried artichoke hearts. Lwt. 2016, 72, 277–284. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S. M.; Brandão, T. R. S.; Silva, C. L. M. Influence of drying processes and pretreatments on nutritional and bioactive characteristics of dried vegetables: A review. Food Eng. Rev, 2016. 8(2), 134–163. [CrossRef]

- El-Sohaimy, S. A. The effect of cooking on the chemical composition of artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.). Afr. J. Food Sci. 2013, 4(8). [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Ríos, P.; Burló, F.; Martínez-Sánchez, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A. Effects of processing on the quality of preserved quartered artichokes hearts. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71(2), 176–180. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Cano, D.; Pérez-Llamas, F.; Frutos, M. J.; Arnao, M. B.; Espinosa, C.; López-Jiménez, J. Á.; Castillo, J.; Zamora, S. Chemical and functional properties of the different by-products of artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) from industrial canning processing. Food Chem. 2014, 160, 134–140. [CrossRef]

- Guida, V.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G.; Chambery, A.; Di Maro, A.; Parente, A. The effects of ohmic and conventional blanching on the nutritional, bioactive compounds and quality parameters of artichoke heads. Lwt. 2013, 53(2), 569–579. [CrossRef]

- Şahin K.; Özcan Sinir G.; Durmus F.; Çopur Ö. The effect of pretreatments and vacuum drying on drying characteristics, total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of artichoke (Cynara cardunculus Var. scolymus L.) slices. Gıda. 2020,2020, :699–709. [CrossRef]

- Muştu, C.; Eren, I. Drying kinetics, heating uniformity and quality changes during the microwave vacuum drying of artichokes (Cynara scolymus L.). Ital. J. Food Sci. 2019, 31(3), 681–702. [CrossRef]

- Borsini, A. A.; Llavata, B.; Umaña, M.; Cárcel, J. A. Artichoke by products as a source of antioxidant and fiber: How it can be affected by drying temperature. Foods. 2021, 10(2), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Icier F. Ohmic blanching effects on drying of vegetable byproduct. J Food Process Eng. 2010, 33(4):661–683. [CrossRef]

- International Standard Organization. Determination of substances characteristics of green and black tea. Part 1: Content of total polyphenols in tea-colorimetric method using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. 2005, (ISO Reference number 14502-1:2005).

- Singleton, V. L.; Rossi, J. A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1965, 16, 144–158. [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M. E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT. 1995, 28(1), 25–30. [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, A. M.; Hussein, R.; Motaal, A. A.; Fouad, M. A.; Aziz, M. A.; El-Sayed, A. Artichoke edible parts are hepatoprotective as commercial leaf preparation. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2018, 28(2), 165–178. [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, I. S. Moisture migration and bulk nutrients interaction in a drying food systems: A Review. Food Nutr Sci. 2014, 05(08), 692–714. [CrossRef]

- Femenia, A.; Robertson, J. A.; Waldron, K. W.; Selvendran, R. R. Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L), globe artichoke (Cynara scolymus) and chicory witloof (Cichorium intybus) processing by-products as sources of dietary fibre. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 77(4), 511–518. [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, H., Hatakeyama, T. Lignin Structure, Properties, and Applications. In: Abe, A., Dusek, K., Kobayashi, S. (eds) Biopolymers. Advances in Polymer Science. 2009, vol 232. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Lutz, M.; Henríquez, C.; Escobar, M. Chemical composition and antioxidant properties of mature and baby artichokes (Cynara scolymus L.), raw and cooked. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24(1), 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Domingo, C. S.; Soria, M.; Rojas, A. M.; Fissore, E. N.; Gerschenson, L. N. Protease and hemicellulase assisted extraction of dietary fiber from wastes of Cynara cardunculus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16(3), 6057–6075. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.; Pandino, G.; Mauromicale, G. Total polyphenol content and antioxidant activity among clones of two sicilian globe artichoke landraces. Acta Hortic. 2013, 983, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Pandino, G., Lombardo, S., & Mauromicale, G.. Globe artichoke leaves and floral stems as a source of bioactive compounds. Ind Crops Prod. 2013, 44, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.; Pandino, G.; Mauro, R.; Mauromicale, G. Variation of phenolic content in globe artichoke in relation to biological, technical and environmental factors. Ital. J. Agron. 2009, 4(4), 181–189. [CrossRef]

- Dosi, R.; Daniele, A.; Guida, V.; Ferrara, L.; Severino, V.; Di Maro, A. Nutritional and metabolic profiling of the globe artichoke (cynara scolymus L. cv. capuanella heads) in province of Caserta, Italy. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2013, 7(12), 1927–1934.

- Kayahan, S.; Saloglu, D. Comparison of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of raw and cooked turkish artichoke cultivars. Front. sustain. food syst. 2021, 5, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Fratianni, F.; Tucci, M.; Palma, M.; De, Pepe, R.; Nazzaro, F. Polyphenolic composition in different parts of some cultivars of globe artichoke (Cynara cardunculus L. var. scolymus (L.) Fiori). Food Chem. 2007, 104(3), 1282–1286. [CrossRef]

- Galieni A.; Stagnari F.; Pisante M.; Platani C.; Ficcadenti N. Biochemical characterization of artichoke (Cynara cardunculus var scolymus L.) spring genotypes from marche and abruzzo regions (central Italy). Adv Hort Sci. 2019, 33(1):23–31. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Fernández, M.; Irigoyen, Á.; Vargas-Alvarez, M. de los A.; Ludwig, I. A.; De Peña, M. P.; Cid, C.. Influence of culinary process on free and bound (poly)phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of artichokes. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 25, 100389. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, M.; Littardi, P.; Cavazza, A.; Santi, S.; Grimaldi, M.; Rodolfi, M.; Ganino, T.; Chiavaro, E. Effect of different atmospheric and subatmospheric cooking techniques on qualitative properties and microstructure of artichoke heads. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137(September), 109679. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H. W.; Pan, Z.; Deng, L. Z.; El-Mashad, H. M.; Yang, X. H.; Mujumdar, A. S.; Gao, Z. J.; Zhang, Q. Recent developments and trends in thermal blanching – A comprehensive review. Inf. Process. Agric. 2017, 4(2), 101–127. [CrossRef]

- Abdulaziz, L.; Yaziji, S.; Azizieh, A. Effect of preliminarily treatments on quality parameters of artichoke with different preservation methods. Int. J. Chemtech Res. 2015, 7(6), 2565–2572.

- Bureau, S.; Mouhoubi, S.; Touloumet, L.; Garcia, C.; Moreau, F.; Bédouet, V.; Renard, C. M. G. C. Are folates, carotenoids and vitamin C affected by cooking? Four domestic procedures are compared on a large diversity of frozen vegetables. Lwt. 2015, 64(2), 735–741. [CrossRef]

- Ferracane, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Visconti, A.; Graziani, G.; Chiavaro, E.; Miglio, C.; Fogliano, V. Effects of different cooking methods on antioxidant profile, antioxidant capacity, and physical characteristics of artichoke. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56(18), 8601–8608. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Monreal, A. M.; García-Diz, L.; Martínez-Tomé, M.; Mariscal, M.; Murcia, M. A. Influence of cooking methods on antioxidant activity of vegetables. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74(3), 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Kweon, M. H.; Hwang, H. J.; Sung, H. C. Identification and antioxidant activity of novel chlorogenic acid derivatives from bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49(10), 4646–4655. [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, V.; Kroon, P. A.; Linsalata, V.; Cardinali, A. Globe artichoke: A functional food and source of nutraceutical ingredients. J. Funct. Foods. 2009, 1(2), 131–144. [CrossRef]

- Schütz, K.; Kammerer, D.; Carle, R.; Schieber, A. Identification and quantification of caffeoylquinic acids and flavonoids from artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) heads, juice, and pomace by HPLC-DAD-ESI/MSn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52(13), 4090–4096. [CrossRef]

- Christaki, E.; Bonos, E.; Florou-Paneri, P. Nutritional and functional properties of cynara crops (globe artichoke and cardoon) and their potential applications: A review. Int. J. Appl. Sci. 2012, 2(2), 64–70. http://www.ttjbiotech.com/pdf/2012nutritional.pdf. Accesed 15 january 2025.

- Francavilla, M.; Marone, M.; Marasco, P.; Contillo, F.; Monteleone, M. Artichoke biorefinery: From food to advanced technological applications. Foods. 2021, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Noriega-Rodríguez, D.; Soto-Maldonado, C.; Torres-Alarcón, C.; Pastrana-Castro, L.; Weinstein-Oppenheimer, C.; Zúñiga-Hansen, M. E. Valorization of globe artichoke (Cynara Scolymus) agro-industrial discards, obtaining an extract with a selective eect on viability of cancer cell lines. Processes. 2020, 8(6). [CrossRef]

- Canale, M.; Sanfilippo, R.; Strano, M. C.; Amenta, M.; Allegra, M.; Proetto, I.; Papa, M.; Palmeri, R.; Todaro, A.; Spina, A. Artichoke industrial waste in durum wheat bread: Effects of two different preparation and drying methods of flours and evaluation of quality parameters during short storage. Foods. 2023, 12(18), 3419. [CrossRef]

- Canale, M.; Spina, A.; Summo, C.; Strano, M. C.; Bizzini, M.; Allegra, M.; Sanfilippo, R.; Amenta, M.; Pasqualone, A. Waste from artichoke processing industry: reuse in bread-making and evaluation of the physico-chemical characteristics of the final product. Plants. 2022, 11(24). [CrossRef]

- Ihl, M.; Monsalves, M.; Bifani, V. Chlorophyllase inactivation as a measure of blanching efficacy and colour retention of artichokes (Cynara scolymus L.). Lwt. 1998, 31(1), 50–56. [CrossRef]

| Control |

Steam (3 min) |

Steam (15 min) |

Immersion (3 min) |

Immersion (15 min) |

|

| Bracts | |||||

| L* | 50.6 ± 0.1 c | 43.2 ± 0.68 d | 52.9 ± 0.36 b | 52.4 ± 0.47 b | 54.1 ± 0.1 a |

| a* | 0.5 ± 0.25 c | 7 ± 0.11 a | 2.4 ± 0.11 b | -2.5 ± 1.3 d | 1.1 ± 0.17 b |

| b* | 22.0 ± 0.17 b | 18.6 ± 0.75 c | 18.6 ± 0.05 c | 26.2 ± 1.2 a | 21.2 ± 0.41 b |

| BI† | 55.8 ± 0.25 c | 67.0 ± 1.4 a | 45.7 ± 0.22 e | 62.3 ± 1.4 b | 49.7 ± 0.95 d |

| TCD‡ | - | 47.5 ± 0.89 a | 56.1 ± 0.34 bc | 58.7 ± 0.95 b | 58.1 ± 0.14 c |

| hº | 1.54 ± 0.01a | 1.21 ± 0.01 c | 1.44 ± 0.1 b | -1.47 ± 0.04 d | 1.51 ± 0.1 a |

| Stems | |||||

| L* | 34.6 ± 0.11 d | 58.2 ± 0.75 b | 61.1 ± 1.5 a | 43.3 ± 1.3 c | 59.6 ± 0.47 ab |

| a* | 3.5 ± 0.51 a | 1.3 ± 0.15 b | 1.5 ± 0.68 b | 3.0 ± 0.1 a | -0.2 ± 0.2 c |

| b* | 14.3 ± 0.34 d | 23.5 ± 0.05 a | 21.0 ± 3.8 ab | 16.7 ± 0.41 cd | 19.0 ± 0.65 bc |

| BI | 59.5 ± 0.21 a | 52.0 ± 0.75 b | 42.9 ± 8.2 c | 52.6 ± 2.4 ab | 37.3 ±1.7 c |

| TCD | 45.5 ± 0.63 a | 46.9 ± 2.8 a | 29.4 ± 1.1 b | 44.6± 0.18 a | |

| hº | 1.33 ± 0.04 c | 1.51 ± 0.1 a | 1.49 ± 0.04 a | 1.39 ± 0.1 b | -1.55 ± 0.01 d |

| Hearts | |||||

| L* | 51.9 ± 0.1 a | 37.0 ± 2.3 d | 46.8 ± 0.05 b | 42.7 ± 0.58 c | 52.9 ± 1.7 a |

| a* | 5.1 ± 0.41 a | 6.4 ± 1.0 a | 2.5 ± 0.47 b | 6.0 ± 1.3 a | 3.2 ± 0.23 b |

| b* | 17.0 ± 0.15 b | 17.5 ± 1.3 b | 16.5 ± 0.63 b | 18.0 ± 1.3 ab | 19.4 ± 1.0 a |

| BI | 46.3 ± 0.34 c | 75.0 ± 2.5 a | 46.5 ± 1.1 c | 63.9 ± 5.6 b | 49.1 ± 3.8 c |

| TCD | 41.5 ± 2.7 a | 49.7 ± 0.23 c | 46.7 ± 1.14 b | 58.7 ± 0.95 c | |

| hº | 1.28 ± 0.02 b | 1.22 ± 0.04 b | 1.42 ± 0.03 a | 1.25 ± 0.05 b | 1.40 ± 0.01 a |

| Bracts | ||||

| TCD† | BI | TPC | TAC | |

| TCD | x | 0,6772 | 0,9274 | 0,0001 |

| BI | 0,6772 | x | 0,6811 | 0,0090 |

| TPC | 0,9274 | 0,6811 | x | 0,5323 |

| TAC | 0,0001 | 0,0090 | 0,5323 | x |

| Stems | ||||

| TCD | BI | TPC | TAC | |

| TCD | x | 0,3508 | 0,9396 | 0,8036 |

| BI | 0,3508 | x | 0,5745 | 0,1068 |

| TPC | 0,9396 | 0,5745 | x | 0,3252 |

| TAC | 0,8036 | 0,1068 | 0,3252 | x |

| Hearts | ||||

| TCD | BI | TPC | TAC | |

| TCD | x | 0,9144 | 0,9274 | 0,3260 |

| BI | 0,9144 | x | 0,9662 | 0,6132 |

| TPC | 0,9274 | 0,9662 | x | 0,3335 |

| TAC | 0,3260 | 0,6132 | 0,3335 | x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).