1. Introduction

There is consistent evidence that the global temperature has risen as human economic activity has intensified. Between 1850 and 2020, the near-surface air temperature of the Earth increased by more than 1.2°C, with the most pronounced rise observed after 1990 (Fischer et al., 2024). Moreover, by the end of this century, global temperatures may rise by up to 5.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018; Maslin et al., 2025).

Paleoclimatic records indicate that the average brain size of Homo species was significantly smaller during warmer periods compared to cooler ones (Stibel, 2023). The brain is metabolically costly and generates a considerable amount of heat relative to its mass (Martin, 1981; Aiello and Wheeler, 1995; Hublin et al., 2015; Dunbar and Shultz, 2017). Therefore, the reduction in brain size associated with warmer climates may reflect an adaptive response to environmental stress driven by natural selection in the context of climate change (Stibel, 2023).

Consistent with these findings, previous neuroimaging studies—mainly based on case reports of patients with heatstroke whose core body temperature exceeded 40 °C—have documented the detrimental effects of extreme heat exposure on the brain, including the brainstem, cerebellum, hippocampus, thalamus, basal ganglia, and specific cortical regions such as the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes (Fushimi et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Mahajan and Schucany, 2008; Ookura et al., 2009; Zhang and Li, 2014; Chang et al., 2020).

In addition, cohort studies have suggested that exposure to extreme heat may represent a potential risk factor for cognitive impairment among older adults (Zhou et al., 2023). For instance, in New England, United States, a 1.5 °C increase in average summer temperature was associated with a 12% rise in hospitalizations related to dementia (Wei et al., 2019). Similarly, in Madrid, Spain, hospital admissions associated with Alzheimer’s disease increased by 23% following days when the maximum temperature exceeded the heatwave threshold (34 °C) by more than 1 °C (Culqui et al., 2017).

Previous studies have shown that heat stress can trigger inflammatory responses—including cellular degeneration and cell death—that may damage brain structures and lead to cerebral atrophy (Walter and Carraretto, 2016). When exposed to high temperatures, the body releases inflammatory mediators as a response to heat-induced stress (Hashim et al., 1997). This release initiates a cascade of inflammatory processes such as vasodilation, tissue swelling, and immune cell infiltration, which can ultimately result in brain atrophy.

Moreover, heat-induced stress amplifies cellular metabolism and stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species, compromising cellular integrity and function while promoting oxidative stress. This oxidative stress further induces lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, DNA damage, and other harmful effects on brain cells, all of which contribute to brain atrophy (Chang et al., 2007; Yang and Lin, 2002).

Most prior studies have primarily focused on the effects of extreme heat (e.g., temperatures exceeding 35 °C), leaving the long-term impact of moderate heat exposure unclear. However, a recent study involving 41,552 participants from the UK Biobank reported that chronic exposure to high ambient temperatures—defined as the proportion of days in the past 20 years when the maximum temperature exceeded 27 °C—was associated with reductions in total gray and white matter volumes, as well as with accelerated age-related brain atrophy (Xiang et al., 2025).

Similarly, prolonged exposure to natural sunlight has been observed to reduce total brain, white matter, and GMV (Li et al., 2024). This association varied by age, sex, and season, being more pronounced among men, individuals under 60 years of age, and during the summer months. Furthermore, longer exposure to sunlight correlated with lower cognitive performance (Li et al., 2024).

This relationship may be explained by the fact that sunlight increases brain temperature through its effects on cerebral blood flow and blood temperature (Nybo et al., 2002; Bain et al., 2015; Piil et al., 2020). Elevated brain temperature alters resting membrane potentials, action potentials, neural conduction velocity, and synaptic transmission (Wang et al., 2015; Brooks, 2005). It can also affect the integrity of the blood–brain barrier and mitochondrial function, thereby reducing the brain’s tolerance to potential injury (Wang et al., 2015).

Even minor changes in brain temperature—less than 1 °C—have been reported to induce functional alterations in various neural regions and to influence conduction velocity and synaptic transmission (Wang et al., 2015). Experimental studies have also shown that direct exposure of the head and neck to sunlight can increase core body temperature by approximately 1 °C and impair motor–cognitive performance (Piil et al., 2020).

Brain temperature is typically 0.5–1 °C higher than core body temperature (Mariak et al., 1994; McIlvoy, 2004). However, when neuroinflammation disrupts the brain’s thermoregulatory mechanisms within specific regions or networks, local tissue temperature can rise by an additional 0.5–1 °C (Annink et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2014; Dietrich et al., 1994; Dietrich et al., 1996). Moreover, localized increases in brain temperature are associated with enhanced leukocyte extravasation, brain edema, and disruption of the blood–brain barrier. Consistent with these pathological processes, patients infected with COVID-19 have shown elevated brain temperature accompanied by reductions in GMV (Sharma et al., 2024). Gray matter atrophy has been linked to cognitive decline in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (Navale et al., 2022; Dicks et al., 2019).

Observational evidence regarding the psychological effects of elevated body temperature is also extensive. For example, an increase of approximately 0.1 °C in core body temperature has been observed during perimenopausal hot flashes and is associated with depressive symptoms (Natari et al., 2018). In the United Kingdom, hospital admissions related to Alzheimer’s disease increased by 4.5% for each 1 °C rise above 17 °C (Gong et al., 2022). Related findings include elevated core body temperature in individuals experiencing depressive episodes (Raison et al., 2015), more pronounced comorbid symptoms among schizophrenia patients on days with higher ward temperatures (Tham et al., 2020), and a 1.7% rise in suicide rates for every 1 °C increase in daily temperature (Thompson et al., 2023). Furthermore, both outdoor and indoor temperatures exceeding 25.7 °C have been shown to significantly impair cognitive performance (Hancock et al., 2007). Together, these findings indicate that temperature is closely associated with human cognition, emotion, and behavior.

Given the ongoing projections of global warming, further research is needed to elucidate the long-term consequences and underlying mechanisms of heat exposure (Fischer et al., 2024), particularly its future impact on brain health (Sisodiya et al., 2024). However, the relationship between core body temperature and brain structure in healthy adults has not yet been investigated. Understanding how small variations in body temperature among individuals who perceive themselves as healthy—rather than among patients with specific diseases or those exposed to extreme environments—relate to differences in GMV may provide meaningful insights. Such knowledge could help individuals recognize environmental issues as personally relevant and motivate behavioral change.

To address this question, the present pilot study examines this relationship in a sample of 27 healthy adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

To achieve a statistical power of 80% with a significance level of 10% for correlation analysis, the required sample size was estimated using G*Power 3.1.9.7. Based on Cohen’s (1988) criterion for a “strong correlation” (effect size r = 0.5), the minimum sample size was calculated to be 21 participants. Following an open call conducted by the BHQ Consortium, an organization for the exchange of brain imaging data and information, a total of 29 individuals (19 men and 10 women; mean age = 39.0 ± 10.1 years) were recruited for this study. Data from 27 individuals (17 men and 10 women; mean age = 38.6 ± 10.3 years), excluding two incomplete responses, were used for the analysis.

All participants were assembled at Tokyo University of Science in June 2025, where they completed an online questionnaire and participated in MRI data acquisition. According to self-reports, none of the participants had any history of neurological, psychiatric, or other medical conditions that could affect the central nervous system.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study, and anonymity was maintained throughout the data collection process. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Brain Informatics Cloud, Tokyo Institute of Science (Human Research Ethics Committee Approval No. 2023137).

2.2. MRI Data Acquisition

MRI data were acquired using a 3-Tesla MRI scanner (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens, Munich, Germany) equipped with a 32-channel head coil. A three-dimensional (3D) T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) pulse sequence was employed, along with spin-echo echo-planar imaging (SE-EPI) using generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisition (GRAPPA). The imaging parameters were as follows: repetition time (TR) = 1900 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.52 ms, inversion time (TI) = 900 ms, flip angle = 9°, matrix size = 256 × 256, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm, and slice thickness = 1 mm.

2.3. MRI Data Analysis

T1-weighted images were processed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12; Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK) implemented in MATLAB R2020b (MathWorks Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA), employing the standard SPM12 tissue probability templates.

The segmented gray matter (GM) images were spatially normalized using diffeomorphic anatomical registration through the exponential Lie algebra (DARTEL) algorithm (Ashburner, 2007). The preprocessing pipeline included a modulation step and spatial smoothing with an 8-mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel.

The smoothed GM images were then proportionally adjusted by dividing each by the intracranial volume (ICV) to obtain proportional GM images. These were used to compute mean and standard deviation (SD) maps. Using this information and the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002), regional GM quotients were averaged to calculate the gray matter–based Brain Healthcare Quotient (GM-BHQ), standardized to have a mean of 100 and an SD of 15. See Nemoto et al. (2017) for more details.

2.4. Core Body Temperature

The pulse-to-pulse interval (PPI) was obtained using an optical sensor embedded in a smartwatch, and the deep body temperature was estimated according to the algorithm developed by Kurosaka et al. (2022).

2.5. Data Analysis

Correlation and partial correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between core body temperature and whole-brain GMV. Given that this was a small-sample pilot study, statistical significance was defined as p < 0.1. This criterion was adopted because the primary purpose of a pilot study is to obtain preliminary information that may guide future large-scale research; therefore, avoiding Type II errors was considered more appropriate than minimizing Type I errors. This decision is consistent with previous studies (Lee et al., 2014), and several recent pilot studies have similarly employed a p-value threshold of < 0.1 for statistical significance (Noorani et al.,2023; Nykänen et al., 2022; Lincoln et al., 2024).

To control for multiple comparisons, both correlation and partial correlation analyses were corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate method. The correlation coefficients were also interpreted in terms of effect size, where r = 0.5 corresponds to a “strong correlation” according to Cohen’s (1988) conventions. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

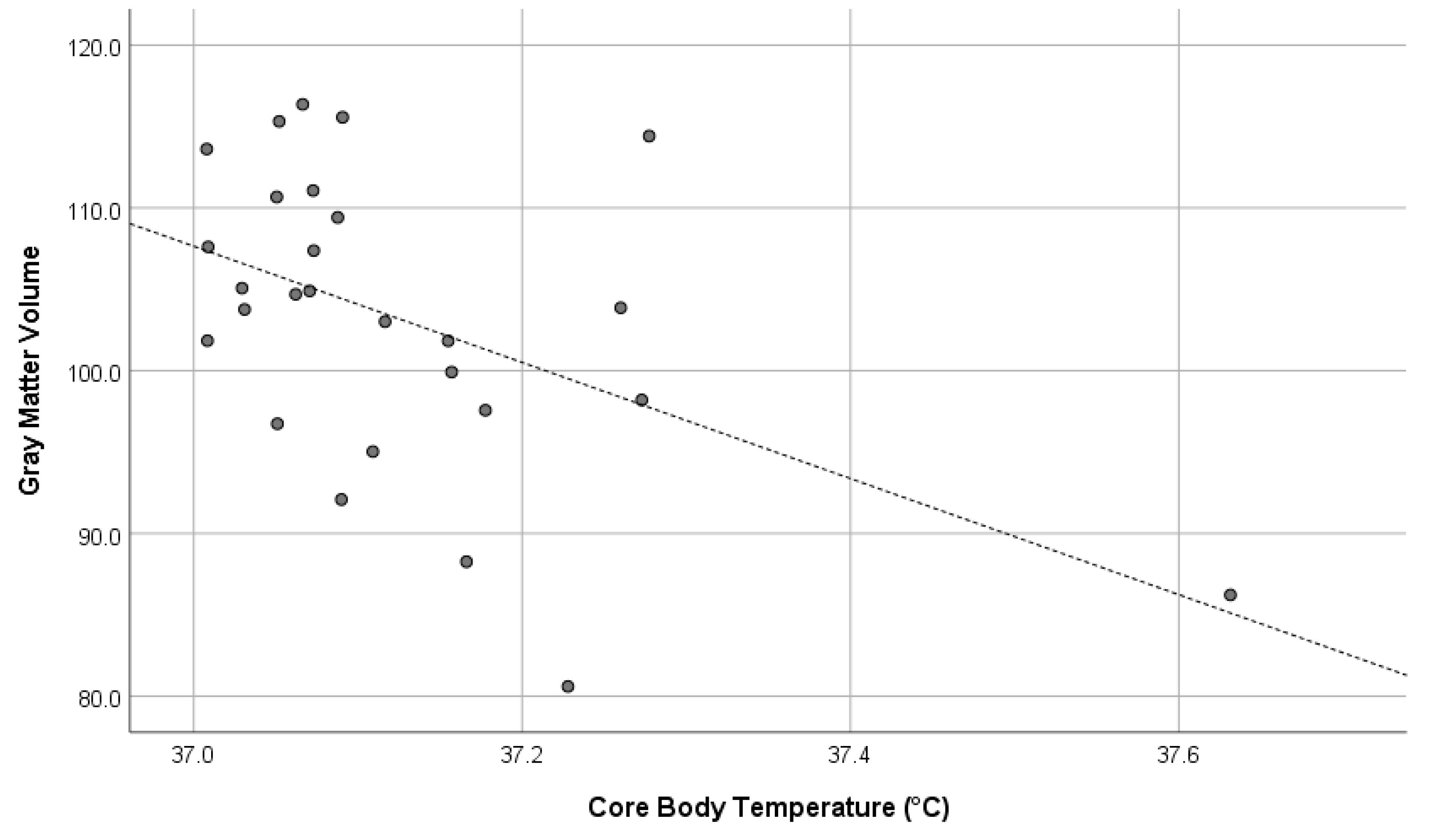

Core body temperature showed a significant negative correlation with whole-brain GMV (r = –0.496, p = 0.009) and a marginally significant partial correlation when controlling for sex and age (r = –0.338, p = 0.099). The former represents the uncontrolled correlation coefficient, while the latter reflects the correlation adjusted for sex and age. These significant results were maintained even after adjusting for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate method.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between core body temperature and whole-brain GMV using a scatter plot.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated a significant negative correlation between core body temperature and whole-brain GMV in healthy adults, and this association remained significant after controlling for sex and age. This finding provides the first evidence, to our knowledge, that even within the normal physiological range, subtle variations in core body temperature are linked to differences in global brain structure.

Previous research has primarily focused on the effects of extreme heat exposure—such as in patients with heatstroke or those living in high-temperature environments—showing that elevated body temperature can lead to neuronal damage, inflammation, and brain atrophy (Walter & Carraretto, 2016; Chang et al., 2007). Moreover, environmental and epidemiological studies have reported that higher ambient temperatures and prolonged sunlight exposure are associated with reduced GMV, increased dementia-related hospitalizations, and cognitive decline (Li et al., 2024; Culqui et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2019). Our results extend these findings by suggesting that brain volume may also be influenced by smaller, everyday variations in body temperature that occur among otherwise healthy individuals.

One possible mechanism underlying this relationship involves thermally induced inflammatory and oxidative processes. Heat exposure has been shown to activate inflammatory mediators and reactive oxygen species, which can disrupt the blood–brain barrier, impair mitochondrial function, and ultimately lead to neuronal damage (Hashim et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2015). Local increases in brain temperature have also been associated with vascular leakage, edema, and tissue injury (Annink et al., 2020; Dietrich et al., 1994). Such mechanisms could explain how even modest elevations in deep body temperature might contribute to microstructural or volumetric changes in gray matter over time.

Another interpretation concerns thermoregulatory efficiency and cerebral metabolism. The brain is a metabolically demanding organ that produces considerable heat relative to its mass (Martin, 1981; Aiello & Wheeler, 1995). Individuals with higher baseline core temperatures might experience greater metabolic strain, requiring more intensive thermoregulatory processes to maintain homeostasis. Over time, this could influence neuronal integrity or glial function, leading to the volumetric patterns observed in the present study.

From a broader perspective, these findings may have important implications for understanding the neurobiological consequences of global warming. As average global temperatures continue to rise (Fischer et al., 2024; IPCC, 2018), even small but chronic elevations in human body temperature could have cumulative effects on brain structure and cognitive health. Importantly, this issue is not confined to individuals with preexisting health conditions but may also affect the general population. Recognizing that body temperature—a physiological variable familiar to everyone—is linked to brain health could make the consequences of global climate change more tangible at the individual level.

The changes that may occur among these individuals could have important implications. Previous studies have shown that GMV is associated with various aspects of functioning in healthy individuals, including cognitive performance (Watanabe et al., 2021), social behavior (Kokubun et al., 2023), job satisfaction (Kokubun et al., 2025), and understanding of diversity (Otsuka et al., 2025). Therefore, GMV reduction potentially induced by global warming may lead to undesirable changes in how we think, work, and cooperate in daily life. Such discussions, however, have not yet been sufficiently explored or empirically examined.

Therefore, this study provides a preliminary but meaningful step toward bridging environmental and neural health research. Future large-scale studies should further investigate how prolonged exposure to elevated environmental temperatures, individual differences in thermoregulation, and lifestyle factors (e.g., hydration, sleep, and physical activity) interact to influence brain structure and function. Longitudinal designs will also be essential to determine whether sustained increases in core body temperature contribute causally to gray matter atrophy and cognitive decline.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small, which is appropriate for a pilot investigation but limits the generalizability of the findings. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples are needed to validate and refine the observed relationship between body temperature and GMV.

Second, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. It remains unclear whether higher body temperature directly leads to reduced GMV, or whether both are influenced by underlying physiological or environmental factors, such as metabolic rate, sleep quality, or circadian rhythm. Longitudinal or experimental studies that manipulate thermal exposure could help clarify causal pathways.

Third, core body temperature was measured at a single time point. Because body temperature fluctuates with circadian rhythms, physical activity, and environmental conditions, repeated or continuous measurements would provide more reliable indices of individual thermal profiles. Integrating multimodal physiological data (e.g., heart rate, skin temperature, inflammatory markers) could also enhance interpretability.

Lastly, MRI-based volumetric analyses capture macroscopic structural variations but do not directly reveal cellular or molecular mechanisms. Combining structural MRI with other modalities—such as diffusion imaging, spectroscopy, or PET—may help uncover the specific neurobiological processes through which thermal factors influence brain integrity.

Despite these limitations, the current findings highlight a previously unexplored link between deep body temperature and global brain structure in healthy adults. This relationship may represent an important physiological pathway through which environmental heat stress contributes to neurobiological vulnerability in a warming world.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this pilot study revealed that higher core body temperature is associated with lower total gray matter volume in healthy adults, suggesting that even minor variations in body temperature may influence brain structure. This finding introduces a novel perspective on how environmental and physiological factors intersect to affect neural health.

Given the ongoing progression of global warming, understanding the subtle yet widespread impacts of heat on the human brain is becoming increasingly urgent. By demonstrating that body temperature—a simple and measurable physiological index—is linked to brain volume, this research underscores the importance of environmental temperature as a determinant of neural health. Ultimately, such insights may help promote public awareness and motivate behavioral and policy changes aimed at mitigating the broader health consequences of a warming planet.

References

- Aiello, L. C. , & Wheeler, P. (1995). The expensive-tissue hypothesis: the brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Current anthropology, 36(2), 199-221.

- Ait Ouares, K., Beurrier, C., Canepari, M., Laverne, G., & Kuczewski, N. (2019). Opto nongenetics inhibition of neuronal firing. European Journal of Neuroscience, 49(1), 6-26. [CrossRef]

- Annink, K. V. , Groenendaal, F., Cohen, D., van der Aa, N. E., Alderliesten, T., Dudink, J.,... & Wijnen, J. P. (2020). Brain temperature of infants with neonatal encephalopathy following perinatal asphyxia calculated using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Pediatric Research, 88(2), 279-284. [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, J. (2007). A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage, 38(1), 95-113. [CrossRef]

- Bain, A. R., Nybo, L., & Ainslie, P. N. (2015). Cerebral vascular control and metabolism in heat stress. Comprehensive Physiology, 5(3), 1345-1380. [CrossRef]

- Bindman, L. J., Lippold, O. C. J., & Redfearn, J. W. T. (1963). Comparison of the effects on electrocortical activity of general body cooling and local cooling of the surface of the brain. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology, 15(2), 238-245. [CrossRef]

- Bouchama, A., & Knochel, J. P. (2002). Heat stroke. New England journal of medicine, 346(25), 1978-1988.

- Brooks, V. B. (2005). Study of brain function by local, reversible cooling. In Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology, Volume 95: Volume: 95 (pp. 1-109). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Chang, C. K., Chang, C. P., Liu, S. Y., & Lin, M. T. (2007). Oxidative stress and ischemic injuries in heat stroke. Progress in brain research, 162, 525-546. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. C., Lee, J., & Kwak, S. (2020). Neural tract injuries revealed by diffusion tensor tractography in a patient with severe heat stroke. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 99(8), e97-e100.

- Cramer, M. N. , Gagnon, D., Laitano, O., & Crandall, C. G. (2022). Human temperature regulation under heat stress in health, disease, and injury. Physiological reviews. [CrossRef]

- Culqui, D. R. , Linares, C., Ortiz, C., Carmona, R., & Díaz, J. (2017). Association between environmental factors and emergency hospital admissions due to Alzheimer's disease in Madrid. Science of The Total Environment, 592, 451-457. [CrossRef]

- Dicks, E. , Vermunt, L., van der Flier, W. M., Visser, P. J., Barkhof, F., Scheltens, P.,... & Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2019). Modeling grey matter atrophy as a function of time, aging or cognitive decline show different anatomical patterns in Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage: Clinical, 22, 101786. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, W. D. , Alonso, O., & Halley, M. (1994). Early microvascular and neuronal consequences of traumatic brain injury: a light and electron microscopic study in rats. Journal of neurotrauma, 11(3), 289-301. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, W. D. , Alonso, O., Halley, M., & Busto, R. (1996). Delayed posttraumatic brain hyperthermia worsens outcome after fluid percussion brain injury: a light and electron microscopic study in rats. Neurosurgery, 38(3), 533-541.

- Dunbar, R. I. , & Shultz, S. (2017). Why are there so many explanations for primate brain evolution?. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1727), 20160244. [CrossRef]

- Egan, G. F. , Johnson, J., Farrell, M., McAllen, R., Zamarripa, F., McKinley, M. J.,... & Fox, P. T. (2005). Cortical, thalamic, and hypothalamic responses to cooling and warming the skin in awake humans: a positron-emission tomography study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(14), 5262-5267. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M. J., Trevaks, D., & McAllen, R. M. (2014). Preoptic activation and connectivity during thermal sweating in humans. Temperature, 1(2), 135-141. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M. J. , Trevaks, D., Taylor, N. A., & McAllen, R. M. (2013). Brain stem representation of thermal and psychogenic sweating in humans. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 304(10), R810-R817. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M. J., Trevaks, D., Taylor, N. A., & McAllen, R. M. (2015). Regional brain responses associated with thermogenic and psychogenic sweating events in humans. Journal of neurophysiology, 114(5), 2578-2587.

- Fischer, S., Naegeli, K., Cardone, D., Filippini, C., Merla, A., Hanusch, K. U., & Ehlert, U. (2024). Emerging effects of temperature on human cognition, affect, and behaviour. Biological Psychology, 189, 108791. [CrossRef]

- Fushimi, Y. , Taki, H., Kawai, H., & Togashi, K. (2012). Abnormal hyperintensity in cerebellar efferent pathways on diffusion-weighted imaging in a patient with heat stroke. Clinical radiology, 67(4), 389-392. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J. , Part, C., & Hajat, S. (2022). Current and future burdens of heat-related dementia hospital admissions in England. Environment international, 159, 107027. [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, M., Nagasaka, K., Nakata, M., Takashima, I., & Yamamoto, S. (2020). Brain temperature alters contributions of excitatory and inhibitory inputs to evoked field potentials in the rat frontal cortex. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 14, 593027. [CrossRef]

- Gursky, O. , & Aleshkov, S. (2000). Temperature-dependent β-sheet formation in β-amyloid Aβ1–40 peptide in water: uncoupling β-structure folding from aggregation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology, 1476(1), 93-102. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, P. A. , Ross, J. M., & Szalma, J. L. (2007). A meta-analysis of performance response under thermal stressors. Human factors, 49(5), 851-877. [CrossRef]

- Hashim, I. A., Al-Zeer, A., Al-Shohaib, S., Al-Ahwal, M., & Shenkin, A. (1997). Cytokine changes in patients with heatstroke during pilgrimage to Makkah. Mediators of Inflammation, 6(2), 135-139. [CrossRef]

- Hayward, J. N., & Baker, M. A. (1969). A comparative study of the role of the cerebral arterial blood in the regulation of brain temperature in five mammals. Brain Research, 16(2), 417-440. [CrossRef]

- Hidaka, S., Gotoh, M., Yamamoto, S., & Wada, M. (2023). Exploring relationships between autistic traits and body temperature, circadian rhythms, and age. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 5888. [CrossRef]

- Hublin, J. J. , Neubauer, S., & Gunz, P. (2015). Brain ontogeny and life history in Pleistocene hominins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1663), 20140062. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018). Global warming of 1.5 °C Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Jung, C. G. , Kato, R., Zhou, C., Abdelhamid, M., Shaaban, E. I. A., Yamashita, H., & Michikawa, M. (2022). Sustained high body temperature exacerbates cognitive function and Alzheimer’s disease-related pathologies. Scientific reports, 12(1), 12273. [CrossRef]

- Kokubun, K. , Nemoto, K., & Yamakawa, Y. (2025). Whole-brain gray matter volume mediates the relationship between psychological distress and job satisfaction. Acta Psychologica, 256, 105059. [CrossRef]

- Kokubun, K., Yamakawa, Y., & Nemoto, K. (2023). The link between the brain volume derived index and the determinants of social performance. Current psychology, 42(15), 12309-12321. [CrossRef]

- Kurosaka, C., Maruyama, T., Yamada, S., Hachiya, Y., Ueta, Y., & Higashi, T. (2022). Estimating core body temperature using electrocardiogram signals. Plos one, 17(6), e0270626. [CrossRef]

- Kusumoto, Y. , Lomakin, A., Teplow, D. B., & Benedek, G. B. (1998). Temperature dependence of amyloid β-protein fibrillization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(21), 12277-12282. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. C. , Whitehead, A. L., Jacques, R. M., & Julious, S. A. (2014). The statistical interpretation of pilot trials: should significance thresholds be reconsidered?. BMC medical research methodology, 14(1), 41. [CrossRef]

- Levine Iii, H. (2004). Alzheimer’s β-peptide oligomer formation at physiologic concentrations. Analytical biochemistry, 335(1), 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Cui, F., Wang, T., Wang, W., & Zhang, D. (2024). The impact of sunlight exposure on brain structural markers in the UK Biobank. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 10313. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zhang, X. Y., Wang, B., Zou, Z. M., Wang, P. Y., Xia, J. K., & Li, H. F. (2015). Diffusion tensor imaging of the cerebellum in patients after heat stroke. Acta Neurologica Belgica, 115(2), 147-150. [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, T. M. , Schlier, B., Müller, R., Hayward, M., Fladung, A. K., Bergmann, N.,... & Pillny, M. (2024). Reducing distress from auditory verbal hallucinations: A multicenter, parallel, single-blind, randomized controlled feasibility trial of relating therapy. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 93(5), 328-339. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S. , & Schucany, W. G. (2008, October). Symmetric bilateral caudate, hippocampal, cerebellar, and subcortical white matter MRI abnormalities in an adult patient with heat stroke. In Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings (Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 433-436). Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Mariak, Z., Lewko, J., Luczaj, J., Polocki, B., & White, M. D. (1994). The relationship between directly measured human cerebral and tympanic temperatures during changes in brain temperatures. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 69(6), 545-549. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. D. (1981). Relative brain size and basal metabolic rate in terrestrial vertebrates. Nature, 293(5827), 57-60. [CrossRef]

- Maslin, M., Ramnath, R. D., Welsh, G. I., & Sisodiya, S. M. (2025). Understanding the health impacts of the climate crisis. Future Healthcare Journal, 12(1), 100240. [CrossRef]

- Mcilvoy, L. (2004). Comparison of brain temperature to core temperature: a review of the literature. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 36(1), 23-31.

- Moser, E., Mathiesen, L., & Andersen, P. (1993). Association between brain temperature and dentate field potentials in exploring and swimming rats. Science, 259(5099), 1324-1326. 5099). [CrossRef]

- Natari, R. B. , Clavarino, A. M., McGuire, T. M., Dingle, K. D., & Hollingworth, S. A. (2018). The bidirectional relationship between vasomotor symptoms and depression across the menopausal transition: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Menopause, 25(1), 109-120. 10.1097/GME.

- Navale, S. S. , Mulugeta, A., Zhou, A., Llewellyn, D. J., & Hyppönen, E. (2022). Vitamin D and brain health: an observational and Mendelian randomization study. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 116(2), 531-540. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, K. , Oka, H., Fukuda, H., & Yamakawa, Y. (2017). MRI-based Brain Healthcare Quotients: A bridge between neural and behavioral analyses for keeping the brain healthy. PLoS One, 12(10), e0187137. [CrossRef]

- Noorani, M. , Bolognone, R. K., Graville, D. J., & Palmer, A. D. (2023). The association between dysphagia symptoms, DIGEST scores, and severity ratings in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Dysphagia, 38(5), 1295-1307. [CrossRef]

- Nunneley, S. A., Martin, C. C., Slauson, J. W., Hearon, C. M., Nickerson, L. D., & Mason, P. A. (2002). Changes in regional cerebral metabolism during systemic hyperthermia in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology, 92(2), 846-851. [CrossRef]

- Nykänen, M. , Kurki, A. L., & Airila, A. (2022). Promoting workplace guidance and workplace–school collaboration in vocational training: a mixed-methods pilot study. Vocations and Learning, 15(2), 317-339. [CrossRef]

- Nybo, L. Nybo, L., Secher, N. H., & Nielsen, B. (2002). Inadequate heat release from the human brain during prolonged exercise with hyperthermia. The Journal of physiology, 545(2), 697-704. [CrossRef]

- Ookura, R. , Shiro, Y., Takai, T., Okamoto, M., & Ogata, M. (2009). Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of a severe heat stroke patient complicated with severe cerebellar ataxia. Internal Medicine, 48(12), 1105-1108. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T. , Kokubun, K., Okamoto, M., & Yamakawa, Y. (2025). The brain that understands diversity: A pilot study focusing on the triple network. Brain Sciences, 15(3), 233. [CrossRef]

- Owen, S. F., Liu, M. H., & Kreitzer, A. C. (2019). Thermal constraints on in vivo optogenetic manipulations. Nature neuroscience, 22(7), 1061-1065. [CrossRef]

- Piil, J. F. , Christiansen, L., Morris, N. B., Mikkelsen, C. J., Ioannou, L. G., Flouris, A. D.,... & Nybo, L. (2020). Direct exposure of the head to solar heat radiation impairs motor-cognitive performance. Scientific reports, 10(1), 7812. [CrossRef]

- Raison, C. L. , Hale, M. W., Williams, L. E., Wager, T. D., & Lowry, C. A. (2015). Somatic influences on subjective well-being and affective disorders: the convergence of thermosensory and central serotonergic systems. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1580. [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtfeger, K. , Von Tiling, S., Kiefer, M., Strowitzki, M., Mestres, P., Booz, K. H., & Steudel, W. I. (1999). Identification of Somatosensory Pathways by Focal-Cooling-Induced Changes of Somatosensory Evoked Potentials and EEG-Activity–an Experimental Study. Acta neurochirurgica, 141(6), 647-654. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Y., & Seidman, D. S. (1990). Field and clinical observations of exertional heat stroke patients. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 22(1), 6-14.

- Sharma, A. A. , Nenert, R., Goodman, A. M., & Szaflarski, J. P. (2024). Brain temperature and free water increases after mild COVID-19 infection. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 7450. [CrossRef]

- Sisodiya, S. M., Gulcebi, M. I., Fortunato, F., Mills, J. D., Haynes, E., Bramon, E., ... & Hanna, M. G. (2024). Climate change and disorders of the nervous system. The Lancet Neurology, 23(6), 636-648. [CrossRef]

- Stibel, J. M. (2023). Climate change influences brain size in humans. Brain Behavior and Evolution, 98(2), 93-106. [CrossRef]

- Tham, S. , Thompson, R., Landeg, O., Murray, K. A., & Waite, T. (2020). Indoor temperature and health: a global systematic review. Public health, 179, 9-17. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. , Lawrance, E. L., Roberts, L. F., Grailey, K., Ashrafian, H., Maheswaran, H.,... & Darzi, A. (2023). Ambient temperature and mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(7), e580-e589. [CrossRef]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer, N. , Landeau, B., Papathanassiou, D., Crivello, F., Etard, O., Delcroix, N.,... & Joliot, M. (2002). Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage, 15(1), 273-289. [CrossRef]

- Walter, E. J., & Carraretto, M. (2016). The neurological and cognitive consequences of hyperthermia. Critical Care, 20(1), 199. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Wang, B., Jackson, K., Miller, C. M., Hasadsri, L., Llano, D.,... & Sutton, B. (2015). A novel head-neck cooling device for concussion injury in contact sports. Translational neuroscience, 6(1), 20-31. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Wang, B., Normoyle, K. P., Jackson, K., Spitler, K., Sharrock, M. F.,... & Du, R. (2014). Brain temperature and its fundamental properties: a review for clinical neuroscientists. Frontiers in neuroscience, 8, 307. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K. , Kakeda, S., Nemoto, K., Onoda, K., Yamaguchi, S., Kobayashi, S., & Yamakawa, Y. (2021). Grey-matter brain healthcare quotient and cognitive function: A large cohort study of an MRI brain screening system in Japan. Cortex, 145, 97-104. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y. , Wang, Y., Lin, C. K., Yin, K., Yang, J., Shi, L.,... & Schwartz, J. D. (2019). Associations between seasonal temperature and dementia-associated hospitalizations in New England. Environment international, 126, 228-233. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W. , Lyu, K., Li, Y., Yin, B., Ke, L., & Di, Q. (2025). Chronic high temperature exposure, brain structure, and mental health: Cross-sectional and prospective studies. Environmental Research, 264, 120348. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Li, Q., Zheng, L., & Li, J. (2022). Diffusion tensor tractography of heatstroke. Acta Neurologica Belgica, 122(1), 211-212. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Y. , & Lin, M. T. (2002). Oxidative stress in rats with heatstroke-induced cerebral ischemia. Stroke, 33(3), 790-794. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Y. , & Li, J. (2014). Susceptibility-weighted imaging in heat stroke. PLoS One, 9(8), e105247. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W. , Wang, Q., Li, R., Zhang, Z., Wang, W., Zhou, F., Ling, L., 2023. The effects of heatwave on cognitive impairment among older adults: Exploring the combined effects of air pollution and green space. Sci. Total Environ. 904, 166534. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).