1. Introduction

Cybersecurity presents a rapidly escalating risk in healthcare, where sensitive patient data, operational dependencies, and outdated infrastructure create significant exposure. Healthcare organizations are increasingly targeted, with more than 60 percent of breaches attributed to human-factor vulnerabilities such as phishing, social engineering, and policy non-compliance [

1,

2,

3]. These threats jeopardize not just privacy and institutional reputation but also disrupt critical care delivery and patient safety.

Investments in technical controls, such as firewalls and endpoint detection, have increased. However, these solutions often miss behavior-driven threats. Human error remains the primary vulnerability, especially in high-pressure settings, with login fatigue and misaligned security procedures [

4]. Despite increased awareness, organizations continue to prioritize technology over interventions that align with workflow and behavior. This can reduce overall cyber resilience.

This study addresses a critical gap: the missing integration of behavioral science in healthcare cybersecurity programs. We apply Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) to examine how security leaders assess and mitigate human-factor risks in real-world contexts. PMT is widely used to study end-user behavior [

5,

6]. Few analyses, however, focus on those who design and enforce enterprise security protocols.

Our primary goal is to provide actionable insights for healthcare cybersecurity leaders. We use qualitative interviews and thematic analysis to identify key barriers and enablers to behavioral compliance. The research provides practical recommendations for aligning security strategies with clinical operations. These findings suggest new approaches to integrating behavioral insights into security frameworks. This approach can strengthen resilience and reduce enterprise risk.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a generic qualitative inquiry approach to explore how cybersecurity professionals perceive and address human-factor vulnerabilities in healthcare organizations. This approach was selected to allow flexibility in gathering nuanced, experience-based insights from practitioners, without being confined to the rigid methodological constraints of traditions such as grounded theory or phenomenology [

7].

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) guided the development of the interview protocol, framing questions around core constructs, including threat appraisal (perceived severity and vulnerability) and coping appraisal (response efficacy and self-efficacy). Thematic analysis was conducted following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework [

8].

2.2. Participants and Sampling

We employed purposive sampling to recruit U.S.-based healthcare professionals with expertise in cybersecurity. Eligible participants had at least three years’ experience and were directly involved in designing, implementing, or enforcing human-factor risk mitigation policies and practices.

Although we originally sought 20 participants, thematic saturation was reached after 10 interviews, as seen in prior healthcare and cybersecurity studies [

9]. The final sample comprised a diverse mix of individuals, including engineers, compliance officers, IT managers, and clinical staff serving on cybersecurity committees.

2.3. Data Collection

Interviews were conducted via Zoom in audio-only format and lasted approximately 45–60 minutes each. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and ethical approval was granted by the Capella University Institutional Review Board (IRB 2025-51). A semi-structured interview guide, reviewed by domain experts, was used to ensure alignment with PMT constructs and the research question.

Example questions included:

“How serious are cybersecurity threats in your current healthcare setting?”;

“What barriers do you encounter when enforcing security policies among non-technical staff?”;

“How confident are you in the effectiveness of your organization’s security training or compliance programs?”.

Following the interviews, recordings were transcribed verbatim and deidentified. All data were then securely stored on encrypted, password-protected servers.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were thematically analyzed using NVivo 12. Thematic analysis used Braun and Clarke’s six steps [

8]:

Data familiarization;

Initial coding;

Preliminary theme identification;

Theme review and refinement;

Final theme naming;

Theme integration into reporting.

A hybrid deductive–inductive coding approach captured both theory-driven and emergent themes. Trustworthiness was enhanced by:

Member checking: Participants reviewed their transcripts for accuracy [

10];

Triangulation: Themes were compared with practitioner reports and relevant literature;

Reflexivity: The researcher kept a journal to note assumptions, decisions, and insights.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report [

11], including respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. Participants were informed of their rights and the voluntary nature of participation. No identifiable information was included in published findings. Data will be retained securely for a minimum of three years, as required by IRB protocol.

3. Results

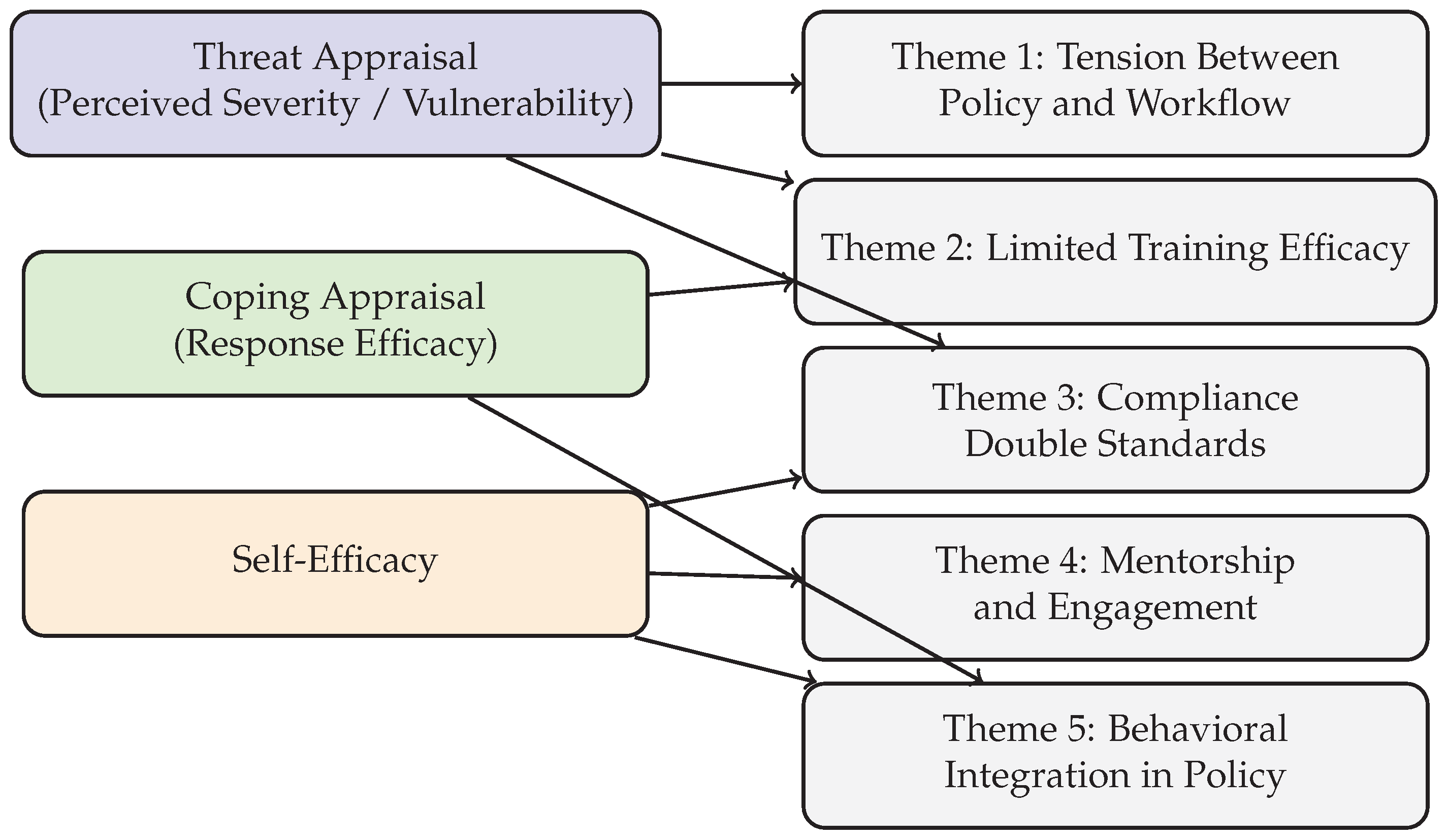

Thematic analysis of ten semi-structured interviews revealed five major themes concerning how cybersecurity professionals perceive and manage human-factor vulnerabilities in healthcare. The themes—(1) tension between policy and workflow; (2) limited efficacy of training; (3) organizational culture and compliance inconsistency; (4) engagement and mentorship; and (5) behavioral integration in cybersecurity policy design—each correspond to specific Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) constructs such as perceived vulnerability, coping response, and self-efficacy. These alignments are illustrated in the findings and supported by representative participant quotes.

Figure 1.

Mapping of Interview Themes to Protection Motivation Theory Constructs.

Figure 1.

Mapping of Interview Themes to Protection Motivation Theory Constructs.

3.1. Tension Between Security Policies and Clinical Workflows

Participants frequently cited conflicts between security requirements and the realities of clinical operations, especially during high-stress scenarios. Multi-factor authentication (MFA), session timeouts, and login requirements were described as disruptive.

“We ask nurses to log in and out constantly. During an emergency, they don’t have time for that, so they share credentials. It’s not ideal, but it happens.” — P4, Nurse on Cybersecurity Committee

This theme illustrates threat appraisal under Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) by showing how participants perceive increased vulnerability to security breaches due to clinical operational constraints.

3.2. Limited Efficacy of Generic Training

Participants widely criticized annual cybersecurity training as ineffective. Training modules were viewed as generic, disengaging, and disconnected from day-to-day responsibilities.

“Annual training feels like a checkbox. People click through slides without reading. It doesn’t stick.” — P9, Senior Cybersecurity Engineer;

“We started using phishing simulations. That gets attention. When someone clicks, they’re more receptive to real conversations.” — P2, Director of Information Security.

This theme highlights low response efficacy (a lack of belief that training methods are effective) and self-efficacy (doubt in one’s personal ability to apply training), reflecting staff concerns about both the content and their preparedness for real threats.

3.3. Organizational Culture and Compliance Double Standards

Several participants described inconsistencies in the enforcement of cybersecurity policies, particularly when leadership or physicians were exempted from rules.

“When management ignores policies or overrides them, others notice. It sets a tone that security is optional.” — P10, Cybersecurity Engineer;

“Doctors get frustrated with MFA. Sometimes IT disables it to avoid conflict.” — P5, Nurse on Cybersecurity Committee.

These practices weaken coping appraisal by signaling that following protocols is unnecessary, which reduces staff’s assessment of their ability and motivation to comply with security requirements.

3.4. Value of Engagement, Visibility, and Mentorship

Participants emphasized the importance of visible and approachable cybersecurity personnel. Embedding IT staff in clinical areas was seen as a way to improve trust and cooperation.

“We have IT liaisons who rotate through departments. It builds trust. People are more likely to report something suspicious.” — P6, Associate Director, EMR Applications;

“Pairing new nurses with experienced staff who understand cybersecurity helps normalize good behavior early on.” — P7, Nurse on Cybersecurity Committee.

This theme indicates that when staff receive visible, relational support—such as embedded IT personnel or peer mentoring—they feel more confident and empowered to use secure practices. These interactions promote self-efficacy and, in turn, increase the likelihood of secure behavior throughout the organization.

3.5. Behavioral Integration in Policy and Technology

Participants advocated for end-user involvement in the creation of policies and technologies. Suggestions included nudges, gamified reminders, and real-time feedback mechanisms.

“Security training should feel relevant. Pop-up reminders for MFA or phishing tips at login screens would be better than long lectures.” — P3, Product Manager with Nursing Background;

“We need policies designed with clinicians, not just for them.” — P1, Help Desk Analyst,

This supports both response efficacy and threat appraisal, as involving end users in co-designing policies and interventions makes compliance more practical and likely.

3.6. Theme Frequency Summary

Table 1.

Presents the frequency of theme mentions across the ten interviews.

Table 1.

Presents the frequency of theme mentions across the ten interviews.

| Theme |

Frequency (Mentions Across Participants) |

| Phishing Concerns |

10 |

| Training Ineffectiveness |

10 |

| Unit-Specific Training Recommendation |

9 |

| IT Staff Training Recommendation |

8 |

| Shared Credential Use |

8 |

| Workflow vs. Compliance Conflict |

8 |

| Inclusion in Policy Creation |

7 |

| Mentorship Value |

7 |

4. Discussion

This study explored how cybersecurity professionals in healthcare settings perceive and mitigate human-factor vulnerabilities. Using Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) as an analytical lens, the findings highlight a shared awareness of behavioral risks—such as phishing, credential misuse, and policy non-compliance—yet also reveal systemic barriers that limit the effectiveness of security interventions. Participants identified key challenges, including policy-workflow misalignment, inconsistent enforcement, and disengaging training programs. At the same time, they emphasized promising strategies, such as unit-specific training, peer mentorship, and participatory policy design.

PMT constructs helped structure these insights. Participants consistently demonstrated strong threat appraisal, recognizing both the likelihood and consequences of cyber incidents in clinical settings. Coping appraisal was more variable. While technical safeguards like multi-factor authentication were appreciated, behavioral interventions often lacked clinical integration or user engagement. Self-efficacy was closely tied to organizational culture, influenced by leadership behavior and the visibility of cybersecurity personnel.

These findings build on prior research examining the behavioral dimensions of cybersecurity in healthcare settings [

4,

9,

12], which similarly highlight challenges such as training fatigue and policy resistance [

6,

13,

14]. Recent reviews underscore the persistent limitations of generic cybersecurity training in healthcare and call for more context-specific and adaptive strategies [

15]. For example, Abouelmehdi et al. (2024) recommend integrating simulation-based and role-tailored learning to better match clinical workflows and user realities.

Unlike much of the existing literature that focuses on end users, this study centers on cybersecurity professionals—those responsible for designing, implementing, and enforcing security protocols. This shift in perspective underscores the influence of institutional dynamics and leadership behavior on the success of behavioral interventions.

Importantly, the study extends PMT’s application beyond individual compliance to encompass organizational governance and leadership. While PMT has traditionally focused on end-user decision-making [

5,

6,

8], these findings show that coping appraisal and self-efficacy are shaped not only by individual perceptions but also by environmental, cultural, and managerial contexts. Recent work by Renaud et al. (2023) advocates for integrating behavioral science more systematically into cybersecurity governance frameworks, reinforcing the need for leadership-driven interventions [

16].

Practical implications include the following recommendations for healthcare organizations:

Design policies that align with clinical workflows and involve frontline staff in their development;

Deliver tiered, interactive training tailored to specific roles and contexts;

Improve IT visibility through embedded personnel or departmental liaisons to build trust;

Implement mentorship programs during onboarding to model secure behaviors.

Theoretical implications suggest that PMT should be integrated with broader frameworks that address environmental, cultural, and structural influences. Overreliance on individual intent, without acknowledging institutional context, may limit the impact of behavioral cybersecurity interventions.

Limitations include the small sample size (n = 10), which, while sufficient for thematic saturation, may restrict generalizability beyond U.S.-based healthcare organizations. Although reflexivity and confidentiality were used to mitigate social desirability bias, it cannot be entirely ruled out.

Future research should compare perspectives across clinical and technical roles, assess long-term impacts of adaptive training programs, and explore the relationship between self-efficacy and behavior change using mixed-method or longitudinal approaches.

5. Conclusions

This study explored how cybersecurity professionals in healthcare perceive and respond to human-factor vulnerabilities, using Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) as a guiding framework. The findings reveal persistent challenges—such as misalignment between workflows and policies, training fatigue, and inconsistent enforcement—that undermine secure behaviors. At the same time, participants emphasized the value of practical, human-centered strategies, including role-specific training, peer mentorship, and participatory policy design.

By focusing on cybersecurity implementers rather than end users, this research addresses a critical gap in the literature. It highlights how institutional culture, leadership behavior, and visibility of cybersecurity personnel shape compliance and policy adoption. Integrating behavioral science with organizational cybersecurity strategy is essential.

For healthcare institutions seeking to strengthen cyber resilience, these results support a shift toward trust-building, workflow-aligned policies, and inclusive governance. Embedding behavioral insights into security frameworks can lead to more sustainable and effective protection against evolving threats.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Capella University (Protocol Code: 2025-51; Date of Approval: 6 March 2025) for studies involving human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Healthcare and Public Health Sector Coordinating Council. Health Industry Cybersecurity Practices: Managing Threats and Protecting Patients (2023 Edition), 2023.

- Ponemon Institute. Cost of a Data Breach Report 2023. https://www.ibm.com/reports/data-breach, 2023. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/reports/data-breach (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Cybersecurity: Challenges and Opportunities for Small Businesses, Field Hearing. Technical report, U.S. Department of Commerce, 2023.

- Kannelønning, K.; Katsikas, S.K. A systematic literature review of how cybersecurity-related behavior has been assessed. Information & Computer Security 2023, 31, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, C.E.; Fisk, N.; Burruss, G.W.; Moule, R.K.; Jaynes, C.M. What motivates users to adopt cybersecurity practices? A survey experiment assessing protection motivation theory. Criminology & Public Policy 2023, 22, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caelli, K.; Ray, L.; Mill, J. “Clear as Mud”: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2003, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, 1979.

- Nowell, L.; Norris, J.; White, D.; Moules, N. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, D.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2006, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, N.S.; Fauzi, M.A.; Hussain, S.; Wider, W. Cybersecurity behavior among government employees: The role of protection motivation theory and responsibility in mitigating cyberattacks. Information 2022, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelmehdi, K.; Beni-Hessane, A.; Khaloufi, H. Cybersecurity Training in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Trends and Effectiveness. Health Informatics Journal 2024, 30, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, K.; Flowerday, S.; Smith, M. Embedding Behavioral Science into Cybersecurity Governance: A Holistic Framework. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 2023, 3, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).