Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

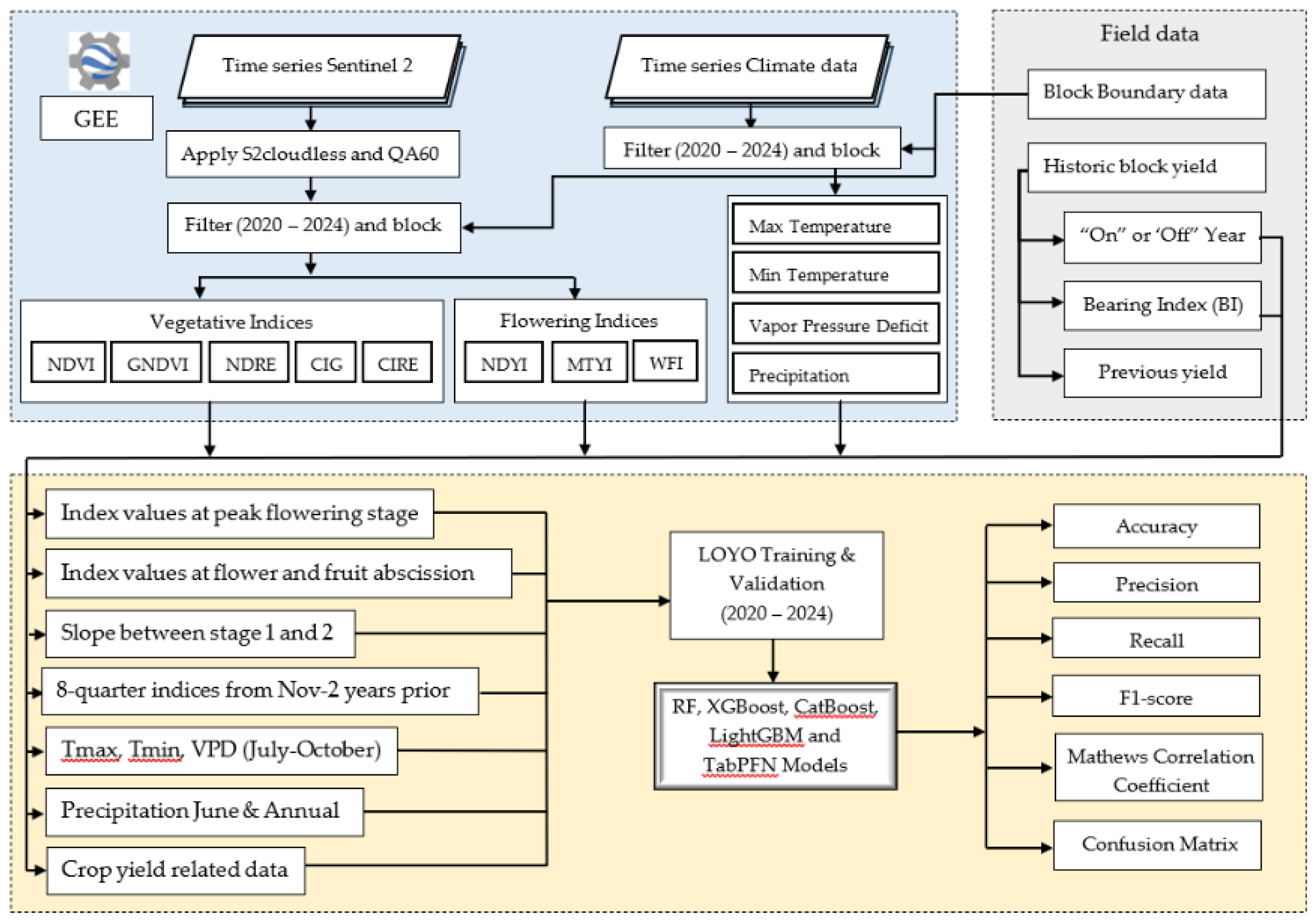

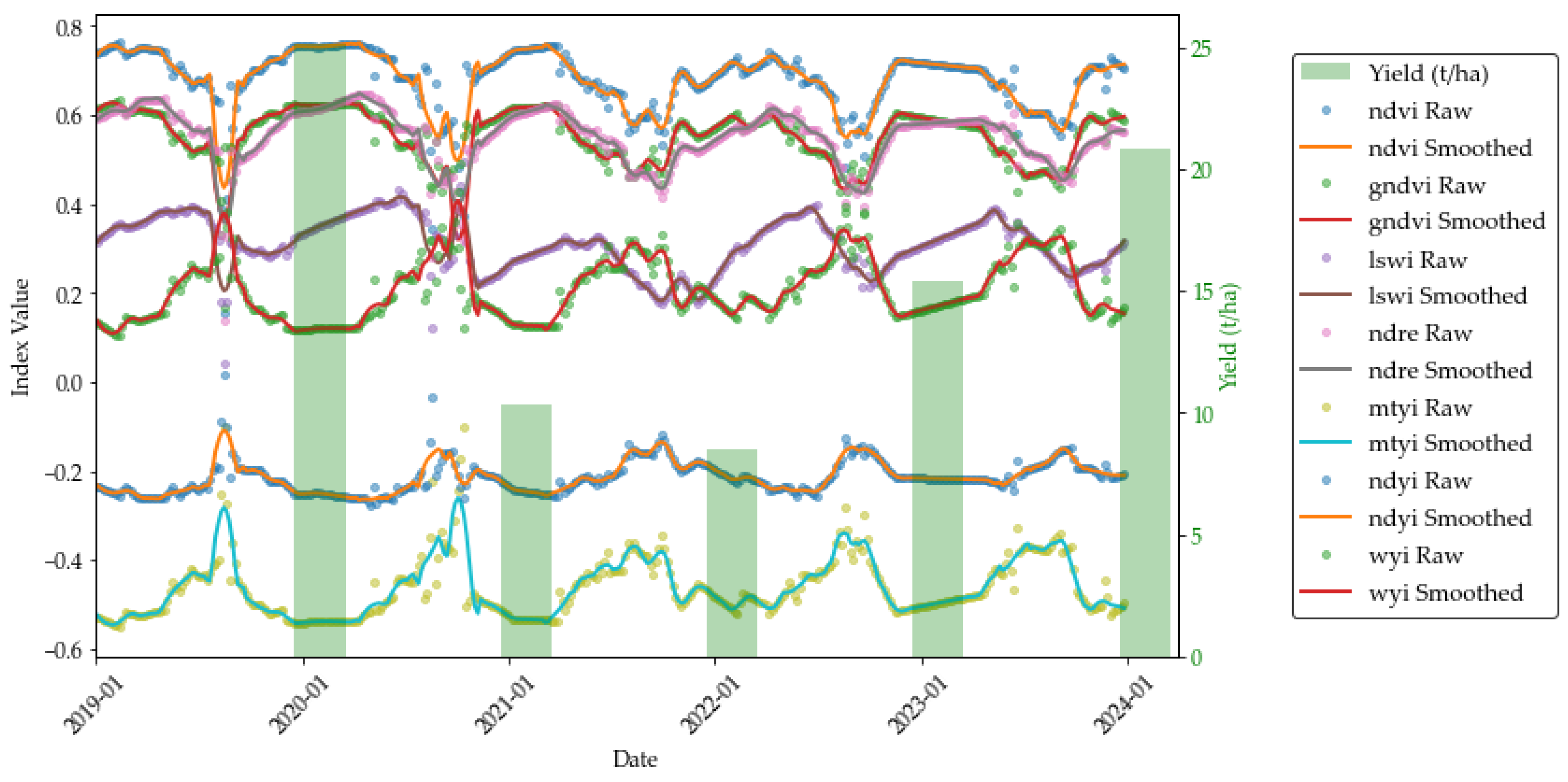

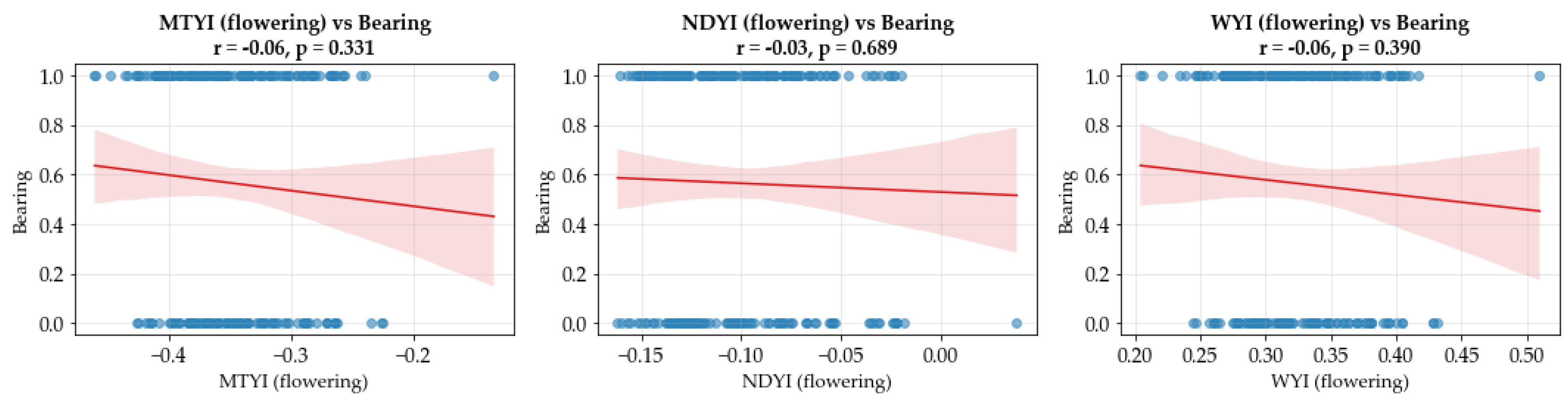

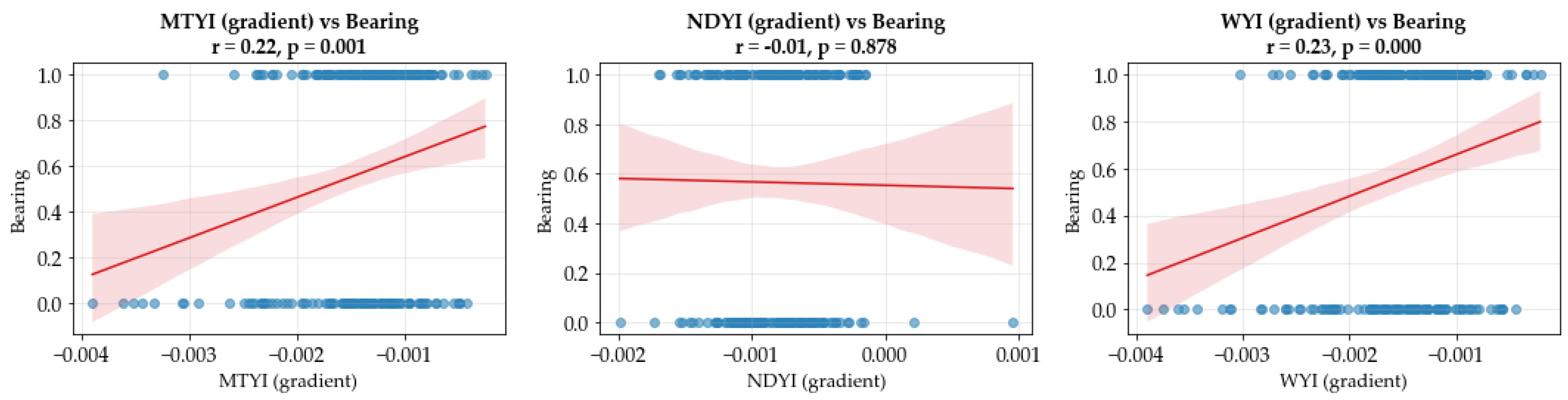

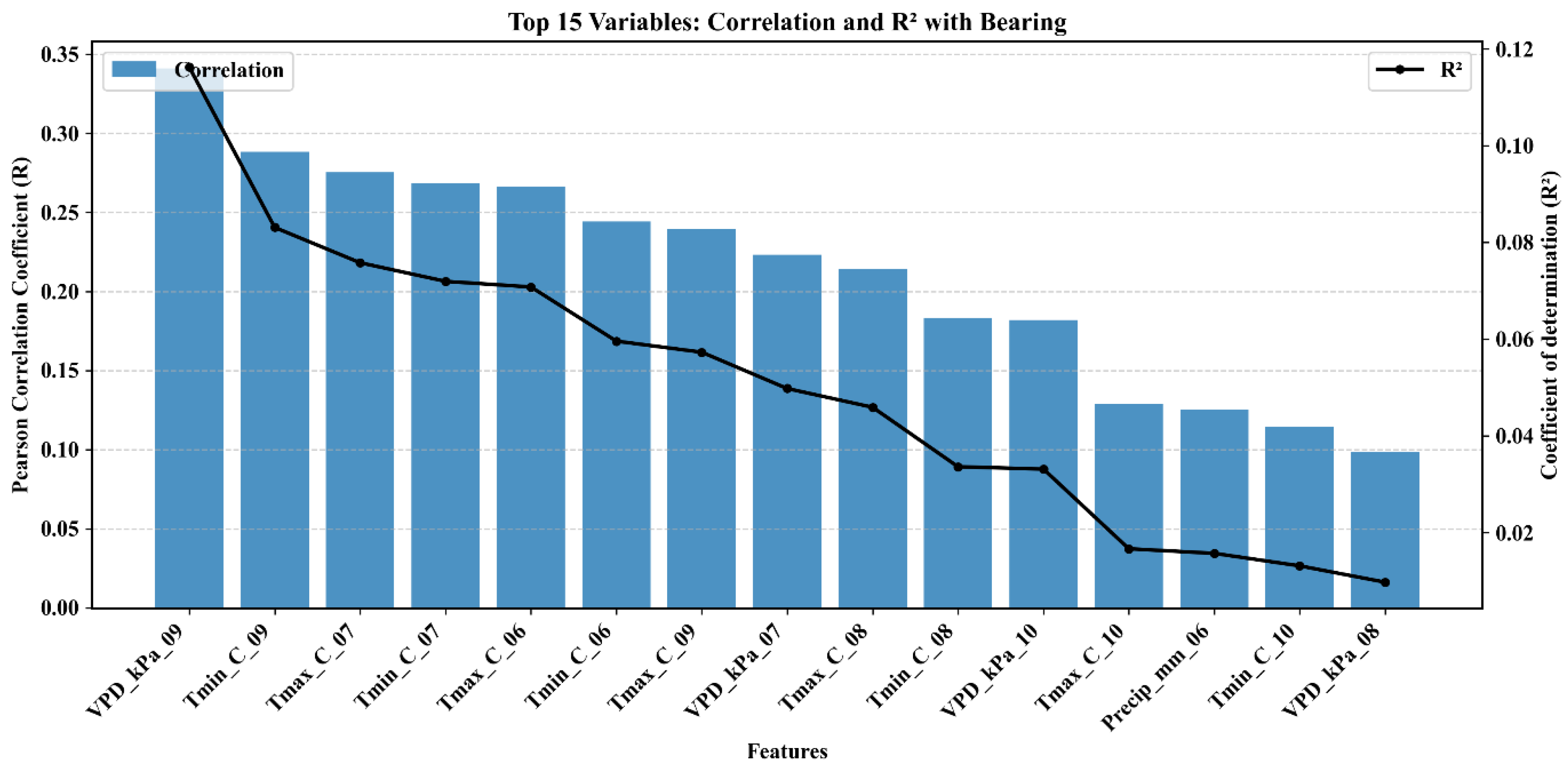

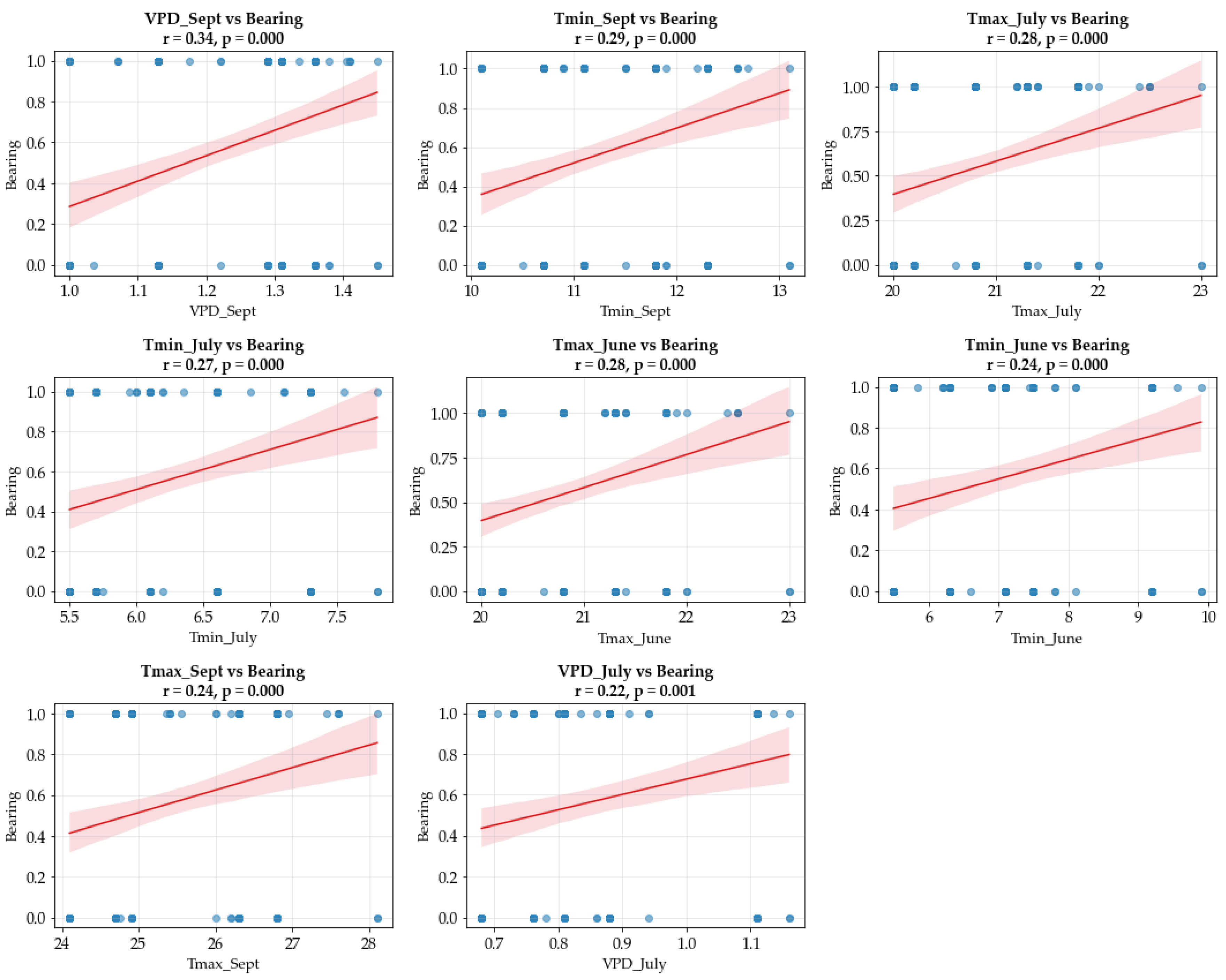

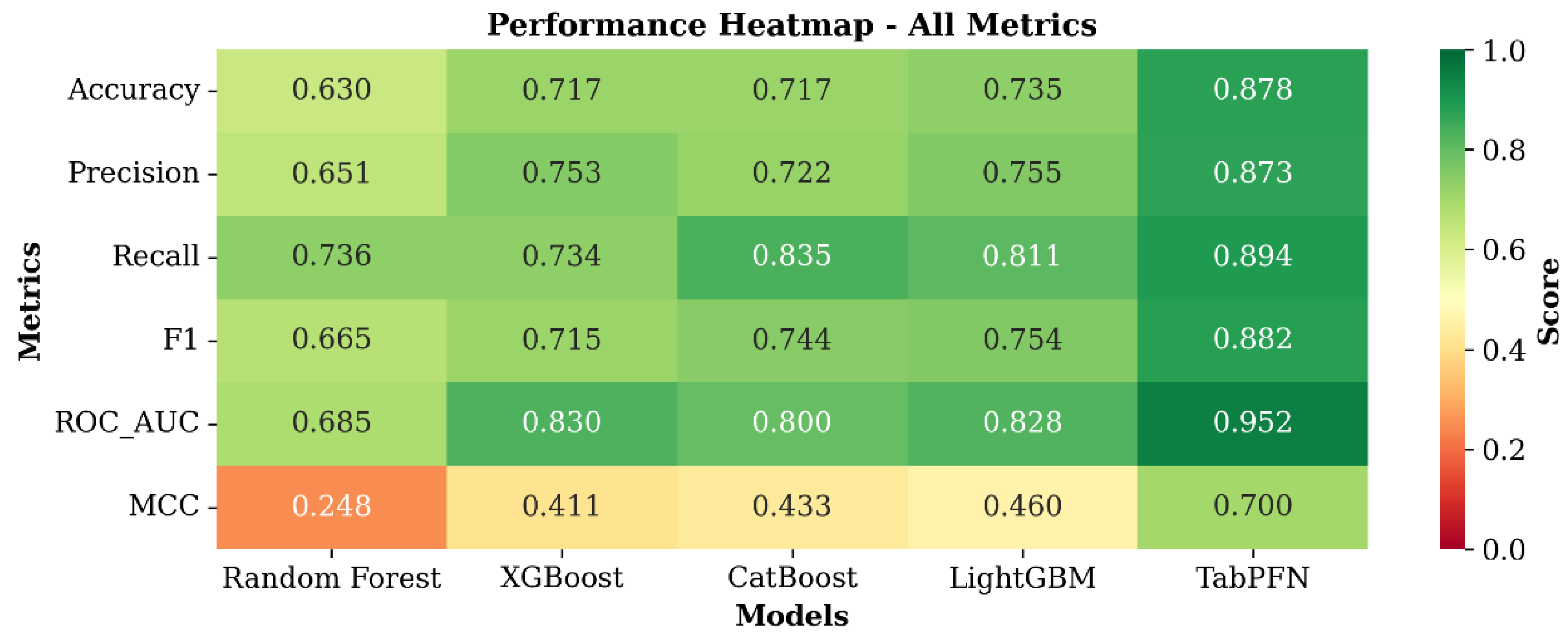

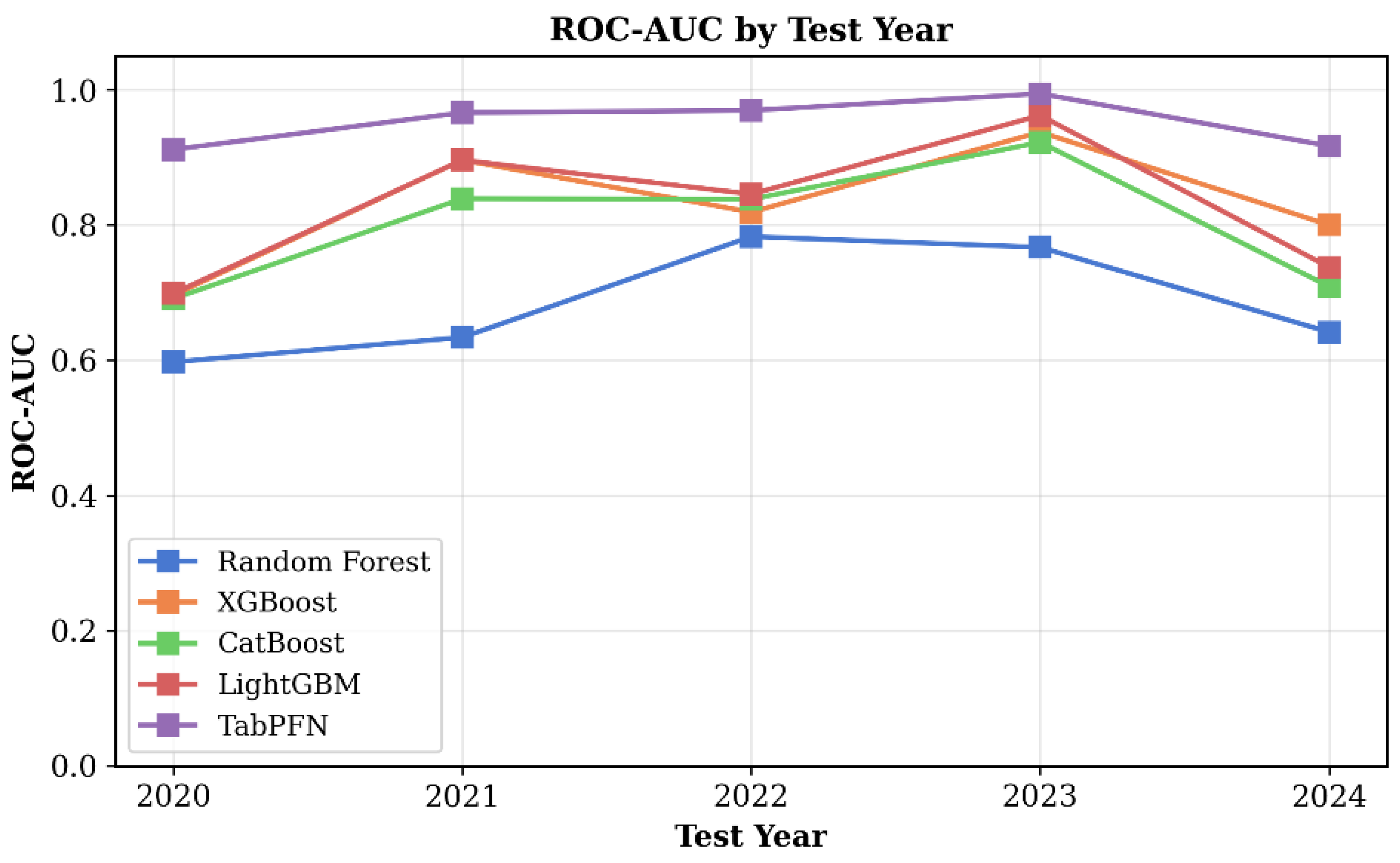

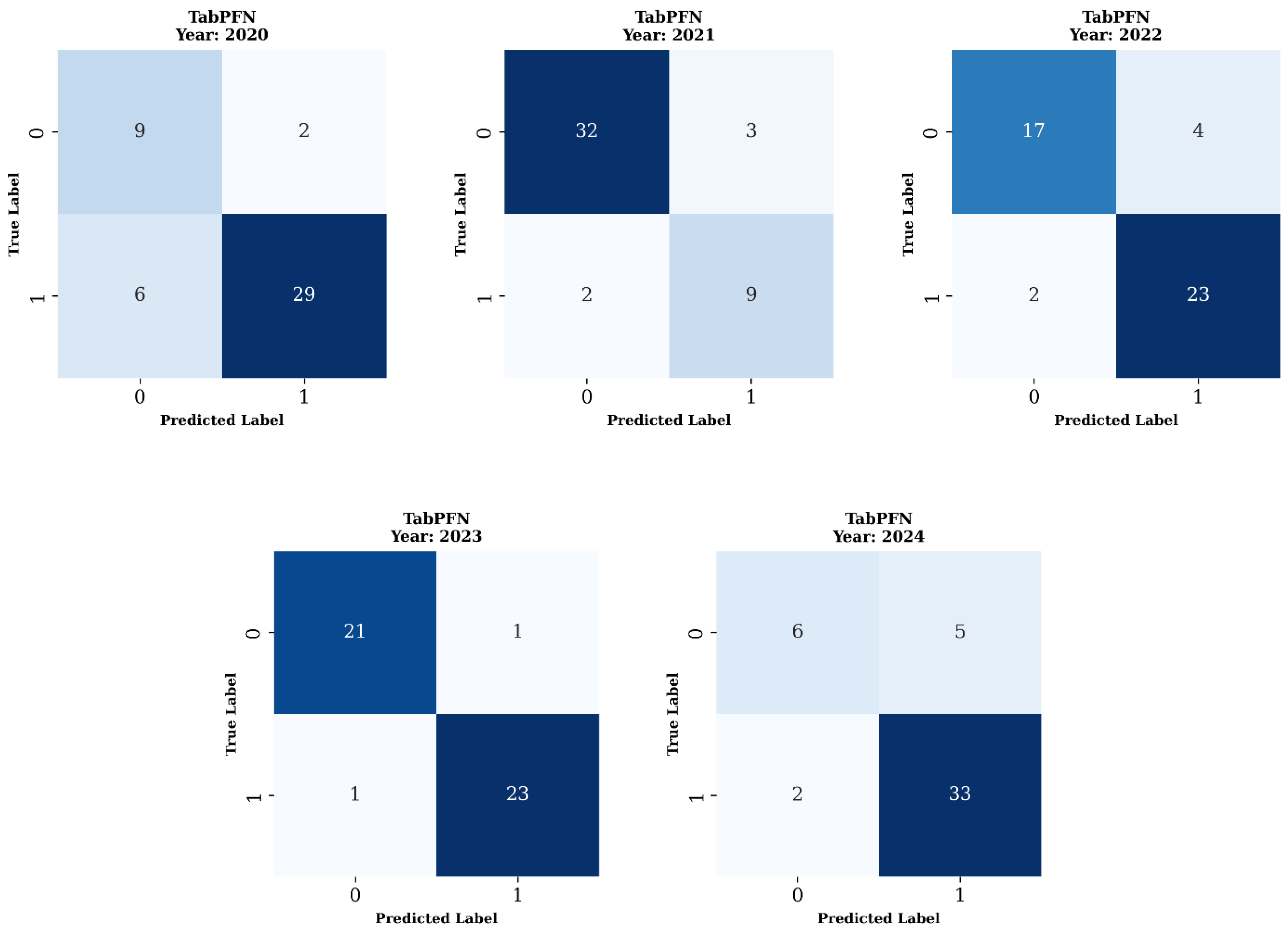

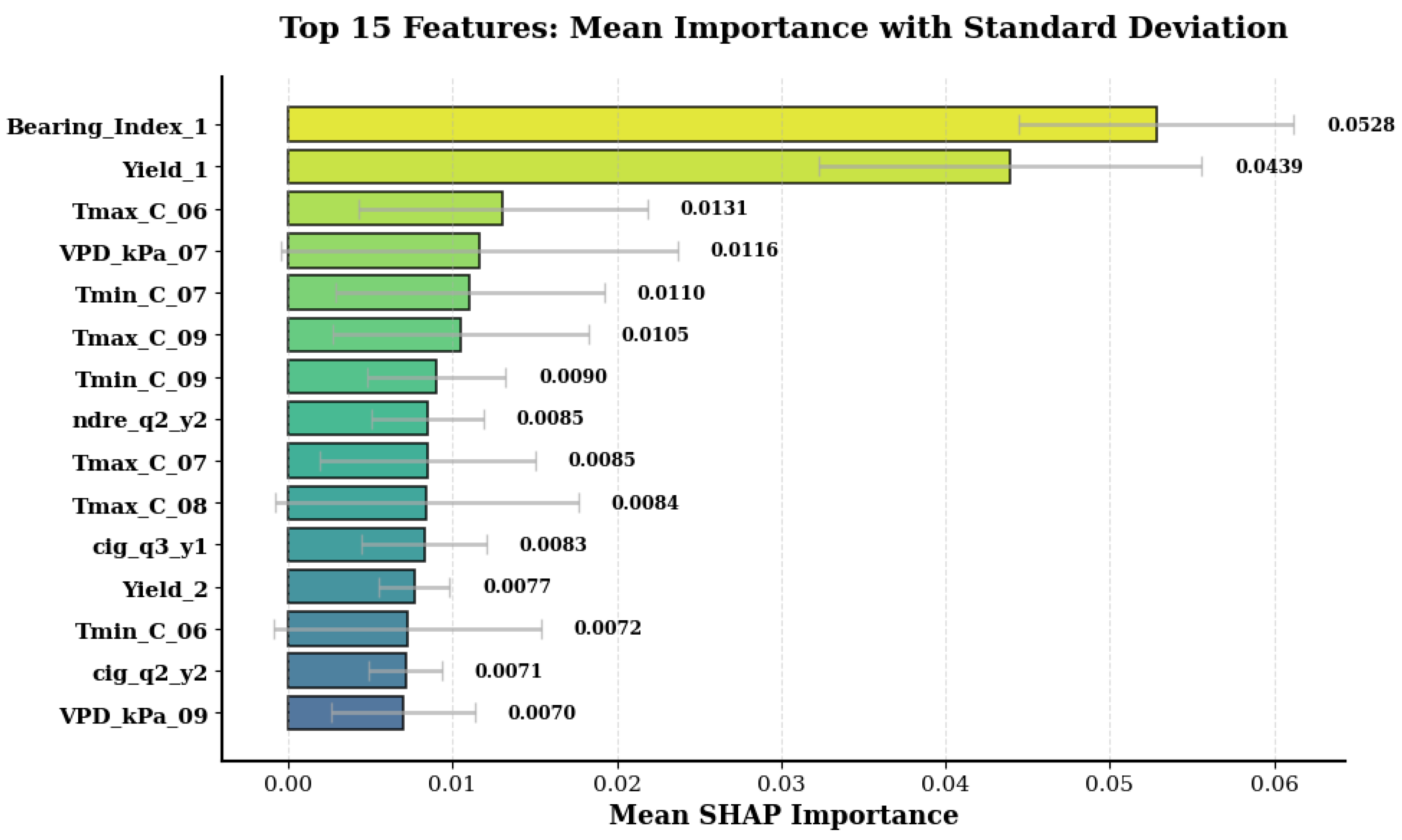

Alternate (irregular) bearing, characterized by large fluctuations in fruit yield between consecutive years, remains a major constraint to sustainable avocado (Persea americana) production. This study aimed to assess the potential of satellite remote sensing and climatic variables to characterize and predict alternate bearing patterns in commercial orchards in Tzaneen, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Historical yield data (2018–2024) from 46 ‘Hass’ avocado blocks were analyzed alongside Sentinel-2 derived vegetation indices (NDVI, GNDVI, NDRE, CIG, CIRE, EVI2, LSWI) and flowering indices (WYI, NDYI, MTYI). Climatic predictors including maximum temperature (Tmax), minimum temperature (Tmin), vapour pressure deficit (VPD), and precipitation were incorporated. Five machine learning algorithms—Random Forest, XGBoost, CATBoost, LightGBM, and TabPFN—were trained and tested using a Leave-One-Year-Out (LOYO) approach. Results showed that VPD, Tmin, and Tmax during the flowering period (July–September) were the most influential variables affecting subsequent yields. TabPFN achieved the highest predictive accuracy (Accuracy = 0.88; AUC = 0.95) and strongest temporal generalization. Spectral gradients between flowering and early fruit drop were lower during “on” years, reflecting stable canopy vigour. These findings demonstrate that integrating remote sensing and climatic indicators enables early discrimination of “on” and “off” years, supporting proactive orchard management and improved yield stability.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Avocado Phenology, Historical Yield and Alternate Bearing

- Years with yield greater than or equal to the median were labeled as “on” year;

- Years with yield less than the median were labeled as “off” year.

2.3. Sentinel 2 Data Acquisition and Spectral Indices

2.3.1. Vegetation and Flowering Indices for Bearing Status Classification

2.3.2. Savitzky-Golay Smoothing

2.4. Climate Data Acquisition

2.5. Model Development

2.5.1. Feature Engineering of Vegetation and Flowering Indices as Well as Climate Variables

- Peak Bloom Stage (August–September) – Maximum values of FIs and minimum values of VIs were extracted, corresponding to the stage of highest flower intensity and lowest vegetative dominance in the study area [29].

- Early Fruit Drop (7–8 weeks after peak flowering) – Minimum values of FIs and maximum values of VIs were computed, reflecting the period when abscission processes are most pronounced and vegetative recovery is underway.

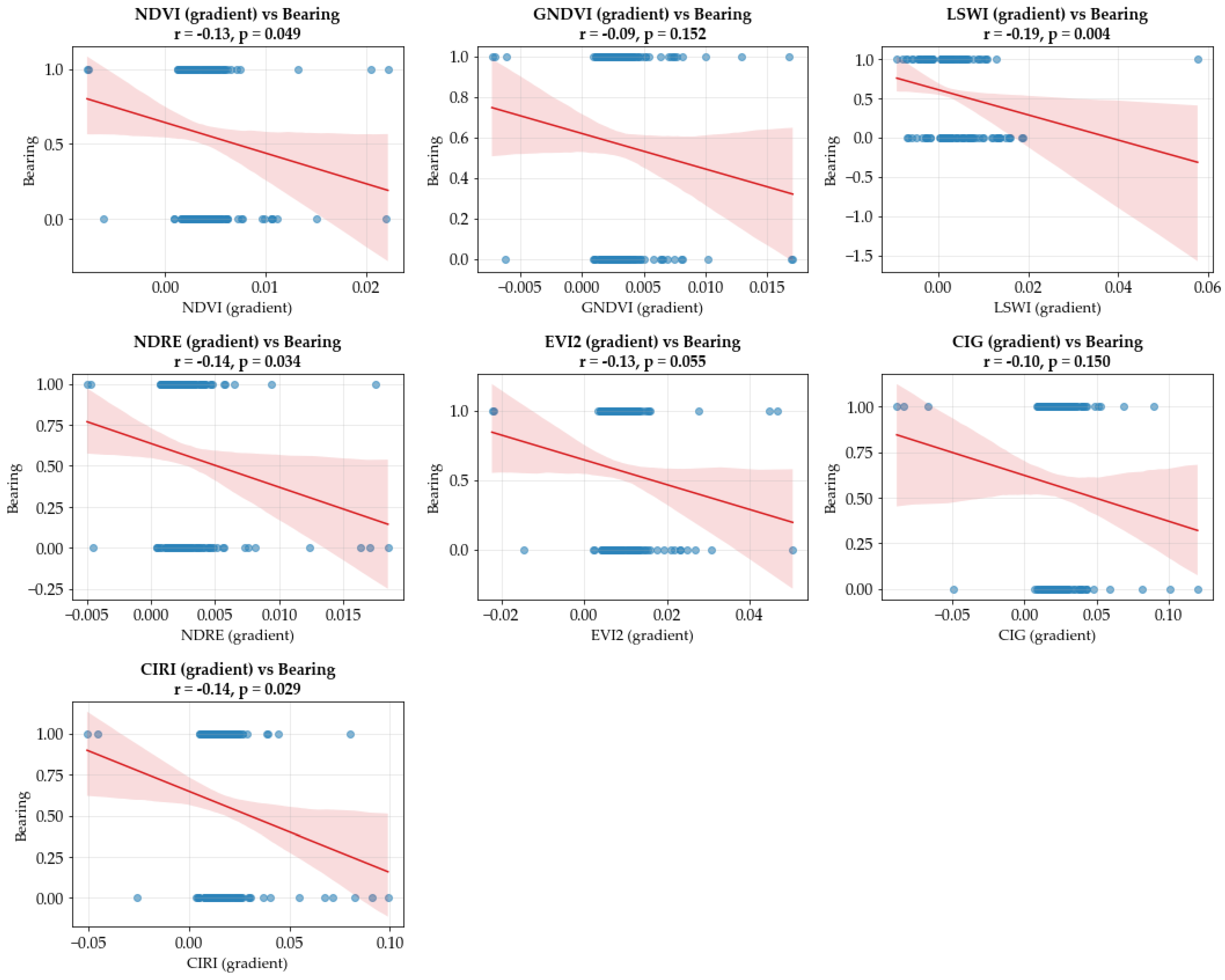

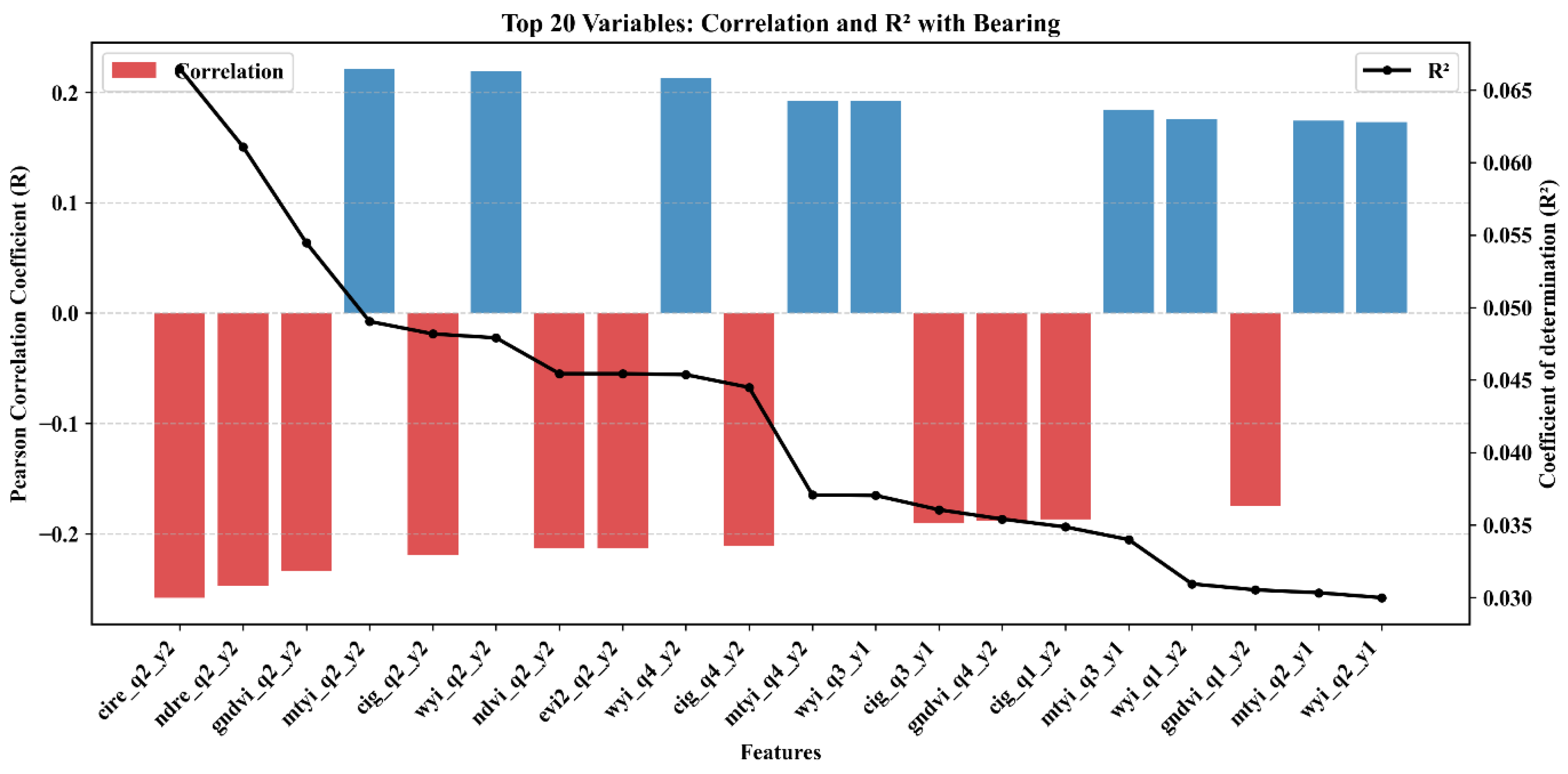

- Temporal Gradient – The rate of change between the two above stages was calculated to capture sharp declines in FIs or distinct peaks in VIs, serving as strong indicators of “on” or “off” years.

2.5.2. Machine Learning Model Algorithms

- Random Forest (RF): RF is an ensemble classifier that constructs multiple decision trees through bootstrap aggregation [65]. Predictions are derived via majority voting across trees, providing resilience against overfitting and robustness in handling noisy, multicollinear datasets. For this study, the number of trees (n_estimators), maximum tree depth, and minimum samples per split were optimized using cross-validation.

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): XGBoost implements gradient boosting with enhanced computational efficiency and regularization[42]. It builds trees sequentially, where each subsequent tree reduces the residual errors of the ensemble. Critical hyperparameters included learning rate, maximum tree depth, subsample fraction, and number of boosting iterations.

- Categorical Boosting (CatBoost): CatBoost extends gradient boosting by incorporating ordered boosting to mitigate overfitting and reduce prediction shift [43]. While originally designed for categorical feature handling, in this study it was applied exclusively to continuous predictors. Hyperparameters such as learning rate, tree depth, and number of iterations were tuned using grid search.

- Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM): LightGBM employs histogram-based feature binning and a leaf-wise growth strategy with depth constraints [44]. These optimizations accelerate training while reducing memory usage. Tuning parameters included number of leaves, maximum depth, feature fraction, and learning rate.

- Tabular Prior Data Fitted Network (TabPFN): TabPFN is a transformer-based neural network trained on millions of synthetic datasets, approximating Bayesian inference for tabular data classification [45]. Unlike conventional algorithms, TabPFN requires minimal parameter adjustment and leverages prior knowledge to achieve strong generalization. In this study, the pretrained TabPFN model was directly applied without additional tuning.

2.5.3. Training and Validation Strategy

2.5.4. Model Evaluation Metrics

- Accuracy: Accuracy measures the overall correctness of the model, defined as the ratio of correctly predicted observations to the total number of observations:

- 2.

- Precision: Precision quantifies the proportion of positive predictions that are actually correct. It is especially important when the cost of false positives is high.

- 3.

- Recall (Sensitivity or True Positive Rate): Recall indicates the proportion of actual positive cases that were correctly identified by the model:

- 4.

- F1-Score: The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall and is a balanced metric for evaluating classification performance when classes are imbalanced:

- 5.

- Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC): The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) is a comprehensive statistical metric that evaluates the quality of binary classifications by considering true and false positives and negatives. It is defined as:

- 6.

- Confusion Matrix: The confusion matrix provides a detailed breakdown of predicted versus actual classes, helping to visualize classification errors:

| Predicted Positive | Predicted Negative | |

| Actual Positive | True Positive (TP) | False Negative (FN) |

| Actual Negative | False Positive (FP) | True Negative (TN) |

- 7.

- Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve and Area Under the Curve (AUC): The ROC curve plots the true positive rate (recall) against the false positive rate across various threshold settings. The AUC quantifies the model's ability to distinguish between classes:

- An AUC of 1.0 indicates perfect classification.

- An AUC of 0.5 suggests no discriminative power.

2.5.5. Model Interpretation

2.5.6. Computational Environment

3. Results

3.1. Temporal Dynamics of Vegetation and Flowering Indices

3.2. Climate Variables and Their Influence

3.3. Model Performance for Alternate Bearing Classification

3.4. Temporal Stabiligy of Models

3.5. Confusion Matrix Analysis

3.5. Feature Importance and Variable Contribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Crops and livestock products. Availabe online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Schwartz, M., Maldonado, Y., Luchsinger, L., Lizana, L.A. and Kern, W. Competitive Peruvian and Chilean avocado export profile. Acta Horticulture 2018, 1194, 1079 - 1084. [CrossRef]

- World'sTopExport. Avocado exports by country. Availabe online: https://www.worldstopexports.com/avocados-exports-by-country/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Kephe, P.N.; Siewe, L.C.; Lekalakala, R.G.; Kwabena Ayisi, K.; Petja, B.M. Optimizing smallholder farmers' productivity through crop selection, targeting and prioritization framework in the Limpopo and Free State provinces, South Africa. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022, 6, 738267.

- Zwane, S.; Ferrer, S.R. Competitiveness analysis of the South African avocado industry. Agrekon 2024, 63, 277-302.

- Wolstenholme, B.N. Alternate bearing in avocado: an overview. Obtenido de: http://www. avocadosource. com/papers/southafrica_papers/wolstenholmenigel2010. pdf 2010.

- Lovatt, C.; Zheng, Y.; Khuong, T.; Campisi-Pinto, S.; Crowley, D.; Rolshausen, P. Yield characteristics of ‘Hass’ avocado trees under California growing conditions. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the VIII World Avocado Congress, Lima, Peru; pp. 13-18.

- Goldschmidt, E.E.; Sadka, A. Yield alternation: horticulture, physiology, molecular biology, and evolution. Horticultural reviews 2021, 48, 363-418.

- Smith, H.M.; Samach, A. Constraints to obtaining consistent annual yields in perennial tree crops. I: Heavy fruit load dominates over vegetative growth. Plant Sci 2013, 207, 158-167. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Abbas, A.; Rehman, A. Alternate bearing in fruit plants. Biol. Agri. Sci. Res. J 2022, 1.

- Jangid, R.; Kumar, A.; Masu, M.M.; Kanade, N.; Pant, D. Alternate Bearing in Fruit Crops: Causes and Control Measures. Asian Journal of Agricultural and Horticultural Research 2023, 10, 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Iturrieta, R.A. First things first: matching an alternate bearing model to confirmed field phenotypes of avocado (Persea americana, Mill.). University of California, Riverside, 2017.

- Lovatt, C. Eliminating alternate bearing of the ‘Hass’ avocado. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the California Avocado Research Symposium. University of California, Riverside, CA, USA; pp. 127-142.

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine learning in agriculture: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674.

- Kamilaris, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2018, 147, 70-90.

- Robson, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Muir, J. Using Worldview Satellite Imagery to Map Yield in Avocado (Persea americana): A Case Study in Bundaberg, Australia. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 1223. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Robson, A.; Brinkhoff, J. Potential of Time-Series Sentinel 2 Data for Monitoring Avocado Crop Phenology. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 5942. [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martimort, P. Sentinel-2: ESA's optical high-resolution mission for GMES operational services. Remote sensing of Environment 2012, 120, 25-36.

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS Proceedings of the Third Earth Resources Technology Satellite- 1 Symposium 1974, 301 317.

- Rahman, M.M.; Robson, A.J. A Novel Approach for Sugarcane Yield Prediction Using Landsat Time Series Imagery: A Case Study on Bundaberg Region. Advances in Remote Sensing, 2016, 5, 93-102. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a two-band enhanced vegetation index without a blue band. Remote sensing of Environment 2008, 112, 3833-3845.

- Delegido, J.; Verrelst, J.; Alonso, L.; Moreno, J. Evaluation of sentinel-2 red-edge bands for empirical estimation of green LAI and chlorophyll content. Sensors 2011, 11, 7063-7081.

- Immitzer, M.; Vuolo, F.; Atzberger, C. First experience with Sentinel-2 data for crop and tree species classifications in central Europe. Remote sensing 2016, 8, 166.

- Lin, S.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, L.; Zhao, J.; Yu, W. Evaluating the effectiveness of using vegetation indices based on red-edge reflectance from Sentinel-2 to estimate gross primary productivity. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 1303.

- Garner, L.C.; Lovatt, C.J. The relationship between flower and fruit abscission and alternate bearing of 'Hass' avocado. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2008, 133, 3-10, doi:Doi 10.21273/Jashs.133.1.3.

- Afsar, M.M.; Iqbal, M.S.; Bakhshi, A.D.; Hussain, E.; Iqbal, J. MangiSpectra: A Multivariate Phenological Analysis Framework Leveraging UAV Imagery and LSTM for Tree Health and Yield Estimation in Mango Orchards. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 703.

- Sulik, J.J.; Long, D.S. Spectral indices for yellow canola flowers. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2015, 36, 2751-2765.

- Salazar-García, S.; Lord, E.M.; Lovatt, C.J. Inflorescence and flower development of the 'Hass' avocado (Persea americana Mill.) during "on" and "off" crop years. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 1998, 123, 537-544.

- Randela, M.Q. Climate change and avocado production: A case study of the Limpopo province of South Africa; University of Pretoria (South Africa): 2018.

- Howden, M.; Newett, S.; Deuter, P. Climate change-risks and opportunities for the avocado industry. In Proceedings of proceedings of the New Zealand and Australian Avocado Grower’s Conference. Holland, P.(Eds.) Tauranga, New Zealand; pp. 1-28.

- Anguiano, C.; Alcántar, R.; Toledo, B.; Tapia, L.; Vidales-Fernández, J. Soil and climate characterization of the avocado-producing area of Michoacán, Mexico. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the VI World Avocado Congress.

- Domínguez, A.; García-Martín, A.; Moreno, E.; González, E.; Paniagua, L.L.; Allendes, G. Identifying Optimal Zones for Avocado (Persea americana Mill) Cultivation in Iberian Peninsula: A Climate Suitability Analysis. Land 2024, 13, 1290.

- Ramírez-Gil, J.G., Henao-Rojas, J.C., & Morales-Osorio, J.G. Mitigation of the adverse effects of the El Niño (El Niño, La Niña) Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon and the most important diseases in avocado cv. Hass crops. Plants 2020, 9, 790. [CrossRef]

- Gafni, E. Effect of extreme temperature regimes and different pollinators on the fertilization and fruit-set processes in avocado. Hebrew University of Jerusalem., 1984.

- Acosta-Rangel, A.; Li, R.; Mauk, P.; Santiago, L.; Lovatt, C.J. Effects of temperature, soil moisture and light intensity on the temporal pattern of floral gene expression and flowering of avocado buds (Persea americana cv. Hass). Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 280, 109940. [CrossRef]

- Sedgley, M.; Grant, W.J.R. Effect of low temperatures during flowering on floral cycle and pollen tube growth in nine avocado cultivars. Scientia Horticulturae 1983, 18, 207-213. [CrossRef]

- Erazo-Mesa, E., Ramírez-Gil, J. G., & Sánchez, A. E. Avocado cv. Hass Needs Water Irrigation in Tropical Precipitation Regime: Evidence from Colombia. Water 2021, 13, 1942. [CrossRef]

- Brinkhoff, J.; Robson, A.J. Block-level macadamia yield forecasting using spatio-temporal datasets. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2021, 303, 108369. [CrossRef]

- Torgbor, B.A., Rahman, M. M., Brinkhoff, J., Sinha, P., & Robson, A. Integrating Remote Sensing and Weather Variables for Mango Yield Prediction Using a Machine Learning Approach. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 3075. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Robson, A.; Bristow, M. Exploring the Potential of High Resolution WorldView-3 Imagery for Estimating Yield of Mango. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1866.

- Jeong, J.H.; Resop, J.P.; Mueller, N.D.; Fleisher, D.H.; Yun, K.; Butler, E.E.; Timlin, D.J.; Shim, K.-M.; Gerber, J.S.; Reddy, V.R., et al. Random Forests for Global and Regional Crop Yield Predictions. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0156571. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, California, USA; pp. 785–794.

- Dorogush, A.V.; Ershov, V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: gradient boosting with categorical features support. ArXiv 2018, abs/1810.11363.

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Hollmann, N.; Müller, S.G.; Eggensperger, K.; Hutter, F. TabPFN: A Transformer That Solves Small Tabular Classification Problems in a Second. In Proceedings of International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Blanco, V.; Blaya-Ros, P.J.; Castillo, C.; Soto-Vallés, F.; Torres-Sánchez, R.; Domingo, R. Potential of UAS-based remote sensing for estimating tree water status and yield in sweet cherry trees. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lazare, S.; Zipori, I.; Cohen, Y.; Haberman, A.; Goldshtein, E.; Ron, Y.; Rotschild, R.; Dag, A. Jojoba pruning: New practices to rejuvenate the plant, improve yield and reduce alternate bearing. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 277, 109793.

- Bernardes, T.; Moreira, M.A.; Adami, M.; Rudorff, B.F.T. Monitoring biennial bearing effect on coffee yield using modis remote sensing imagery. 2012 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium 2012, 3760-3763.

- Myeni, L.; Mahleba, N.; Mazibuko, S.; Moeletsi, M.E.; Ayisi, K.; Tsubo, M. Accessibility and utilization of climate information services for decision-making in smallholder farming: Insights from Limpopo Province, South Africa. Environmental Development 2024, 51, 101020. [CrossRef]

- Bunce, B. Municipal case study: Greater Tzaneen Local Municipality, Limpopo. GTAC/CBPEP/ EU project on employment-intensive rural land reform in South Africa: policies, programmes and capacities. 2020.

- Kotze, J. Phases of seasonal growth of the avocado tree. Research Report, South African Avocado Growers’ Association 1979, 3, 14–16.

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 202, 18 - 27. [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In Proceedings of Third Earth Resources Technology Satellite-1 Symposium - Volume I: Technical Presentations. NASA SP-351, NASA: Washington, DC, USA; pp. 309-317.

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sensing of Environment 1996, 58, 289-298. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.; Clarke, T.; Richards, S.; Colaizzi, P.; Haberland, J.; Kostrzewski, M.; Waller, P.; Choi, C.; Riley, E.; Thompson, T., et al. Coincident detection of crop water stress, nitrogen status and canopy density using ground-based multispectral data. P. C. Robert, R.H.R.W.E.L., Ed. Madison American Society of Agronomy: 2000; pp. 1–15.

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. Journal of Plant Physiology 2003, 160, 271-282. [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.C. NDWI - A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sensing of Environment 1996, 58, 257-266, doi:Doi 10.1016/S0034-4257(96)00067-3.

- Fernando, H.; Ha, T.; Attanayake, A.; Benaragama, D.; Nketia, K.A.; Kanmi-Obembe, O.; Shirtliffe, S.J. High-Resolution Flowering Index for Canola Yield Modelling. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4464.

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Analytical chemistry 1964, 36, 1627-1639.

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Scientific Data 2018, 5, 170191. [CrossRef]

- Garner, L.C.; Lovatt, C.J. The Relationship Between Flower and Fruit Abscission and Alternate Bearing of ‘Hass’ Avocado. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2008, 133, 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O., & Kegelmeyer, W. P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2002, 16, 321–357. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, Q.; Fan, Z. A novel oversampling technique for class-imbalanced learning based on SMOTE and natural neighbors. Inf. Sci. 2021, 565, 438–455. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.e.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V., et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825-2830.

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5-32. [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Information Processing & Management 2009, 45, 427-437. [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. ArXiv 2011, abs/2010.16061.

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0118432. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, A.P. The use of the area under the ROC curve in the evaluation of machine learning algorithms. Pattern Recognition 1997, 30, 1145-1159. [CrossRef]

- Monselise, S.P., & Goldschmidt, E. E. Alternate bearing in fruit trees. Horticultural reviews 1982, 4, 128-173.

- Whiley, A. Crop management. CABI 2002, 10.1079/9780851993577.0231, 231–258. [CrossRef]

- Whiley, A.W.; Rasmussen, T.S.; Saranah, J.B.; Wolstenholme, B.N. Delayed harvest effects on yield, fruit size and starch cycling in avocado (Persea americana Mill.) in subtropical environments. I. the early-maturing cv. Fuerte. Scientia Horticulturae 1996, 66, 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Silber, A.; Naor, A.; Cohen, H.; Bar-Noy, Y.; Yechieli, N.; Levi, M.; Noy, M.; Peres, M.; Duari, D.; Narkis, K., et al. Irrigation of ‘Hass’ avocado: effects of constant vs. temporary water stress. Irrigation Science 2019, 37, 451-460. [CrossRef]

- Sommaruga, R.; Eldridge, H.M. Avocado Production: Water Footprint and Socio-economic Implications. EuroChoices 2021, 20, 48-53. [CrossRef]

- Lavee, S. Biennial bearing in olive (Olea europaea). Annales : Series Historia Naturalis 2007, 17, 101-112.

- Goldschmidt, E.E. Fifty Years of Citrus Developmental Research: A Perspective. HortScience 2013, 48, 820-824. [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, B.A.; Wolstenholme, B.N.; Whiley, A.W. The avocado: botany, production and uses; CABI: 2013.

| Index | Description | Sentinel 2 Formula | Purpose | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index | Canopy vigour, and biomass | [53] | |

| GNDVI | Green normalized difference vegetation index | Canopy vigour, and biomass | [54] | |

| NDRE | Normalized difference red edge index | Chlorophyll content and photosynthetic activity | [55] | |

| CIG | Chlorophyll Index Green | Canopy chlorophyll content | [56] | |

| CIRE | Chlorophyll Index Red Edge | Canopy chlorophyll content | [56] | |

| EVI2 | Enhance Vegetation Index 2 | High biomass minimizing soil and atmosphere influences | [21] | |

| LSWI | Land Surface Water Index | Water content in vegetation | [57] | |

| WYI | Weighted yellowness index | Flowering detection (yellow reflectance) | [26] | |

| NDYI | Normalized Difference Yellowness Index | Flower pigment contrast | [58] | |

| MTYI | Mango tree yellowness index | Tree flowering index | [26] |

| Model | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | n_estimators | 500 |

| max_depth | 4 | |

| min_samples_split | 20 | |

| XGBoost | n_estimators | 100 |

| learning_rate | 0.1 | |

| max_depth | 4 | |

| CatBoost | iterations | 600 |

| learning_rate | 0.05 | |

| depth | 6 | |

| LightGBM | n_estimators | 200 |

| learning_rate | 0.05 | |

| max_depth | 6 | |

| TabPFN | configuration | Default pretrained model (no tuning) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).