Introduction

Open Science is a movement that advocates for transparency, accessibility, and collaboration across all stages of the scientific process [

1]. By removing paywalls, intellectual property restrictions, and closed access to research outputs, Open Science aims to accelerate scientific progress and ensure that its benefits are distributed more equitably [

2]. Researchers, institutions, funders, and publishers contribute to this model through practices such as open access publishing, data sharing, open-source software development, and collaborative peer review [

3,

4].

Despite its significant benefits, the adoption of Open Science practices remains uneven across the research community and numerous studies have sought to identify the roadblocks and barriers researchers face [

5]. However, much of this literature focuses narrowly on publication-related outputs, leaving material sharing, the distribution of renewable and non-renewable biological or chemical materials, an underexplored pillar of Open Science. Here, “renewable” refers to resources that can be replenished or reproduced, such as plasmids and cell lines, while “non-renewable” materials include finite resources like patient-derived tissues or unique biological samples. Unlike publications or datasets, materials often require substantial effort and resources to generate and cannot always be duplicated, making their sharing both more valuable and challenging [

6,

7].This gap is particularly relevant for global Open Science initiatives such as Target 2035, Addgene, and the Chemical Probe Portal, which depend on widespread researcher contributions of biological materials to achieve their aims [

8,

9,

10].

The Target 2035 project seeks to “develop a pharmacological modulator for every protein in the human proteome by 2035”, and relies on contributions of protein samples and reagents from external institutions to populate its Open Science ligand discovery platforms [

11,

12]. A recent white paper on the next phase of this project emphasized that approximately 25% of the proteins to be screened in Target 2035 will originate from community contributions, underscoring how external researcher participation and resource sharing is central to the initiative’s success [

13]. Studying the factors that enable or hinder this contribution process is therefore essential to achieving the goals of Target 2035 and ensuring sustainable Open Science practices (

Figure 1).

While some researchers are willing contributors, others remain reluctant to share proteins they have developed for screening in initiatives such as Target 2035. To address this gap, this study sought to examine researchers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceived barriers toward material sharing, and to identify possible incentives and structural supports that could encourage broader participation in Open Science and Open Materials.

This pilot study sought to address three key objectives: [

1] to evaluate researchers’ understanding and perceptions of Open Science and Open Materials; [

2] to identify barriers such as legal, logistical, and reputational hurdles, that deter participation; and [

3] to assess whether tailored incentive systems, including recognition, collaboration opportunities or funding, might shift researchers’ willingness to contribute Open Materials to large-scale Open Science endeavours. By examining these issues, the study contributes to advancing the mission of Target 2035 and other Open Science initiatives by helping to improve community participation, demonstrating how strategies to enhance material sharing can support its success and, more broadly, be translated to strengthen participation in other Open Science initiatives.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval

The survey and research protocol were developed in accordance with the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (REB) standards and was approved (RIS Number: 47610). No personally identifiable information was collected, ensuring full anonymity of respondents and preventing any correlation between responses and individual identities. At the beginning of the survey, participants were provided with detailed information about potential risks, confidentiality, voluntary participation, the right to withdraw, and provision of consent. Information about the research institution, principal investigator, and contact details was included in both the survey and the distribution emails. The complete survey and research protocols were submitted to and approved by the University of Toronto REB (see

Appendix A2).

Survey Distribution and Recruitment

The survey was distributed electronically using Google Forms. It was circulated to researchers involved in protein science and structural biology through professional mailing lists, departmental distribution at the University of Toronto, protein science communities, and direct invitations to individual domain expert researchers (see

Appendix A3).

Analysis of Survey Data

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations to assess links between demographics, Open Science awareness, material-sharing behavior, and support for reward systems, with the aim of identifying the key incentives and barriers to participation.

Results

Response Rate of Pilot Survey and Demographics of Respondents

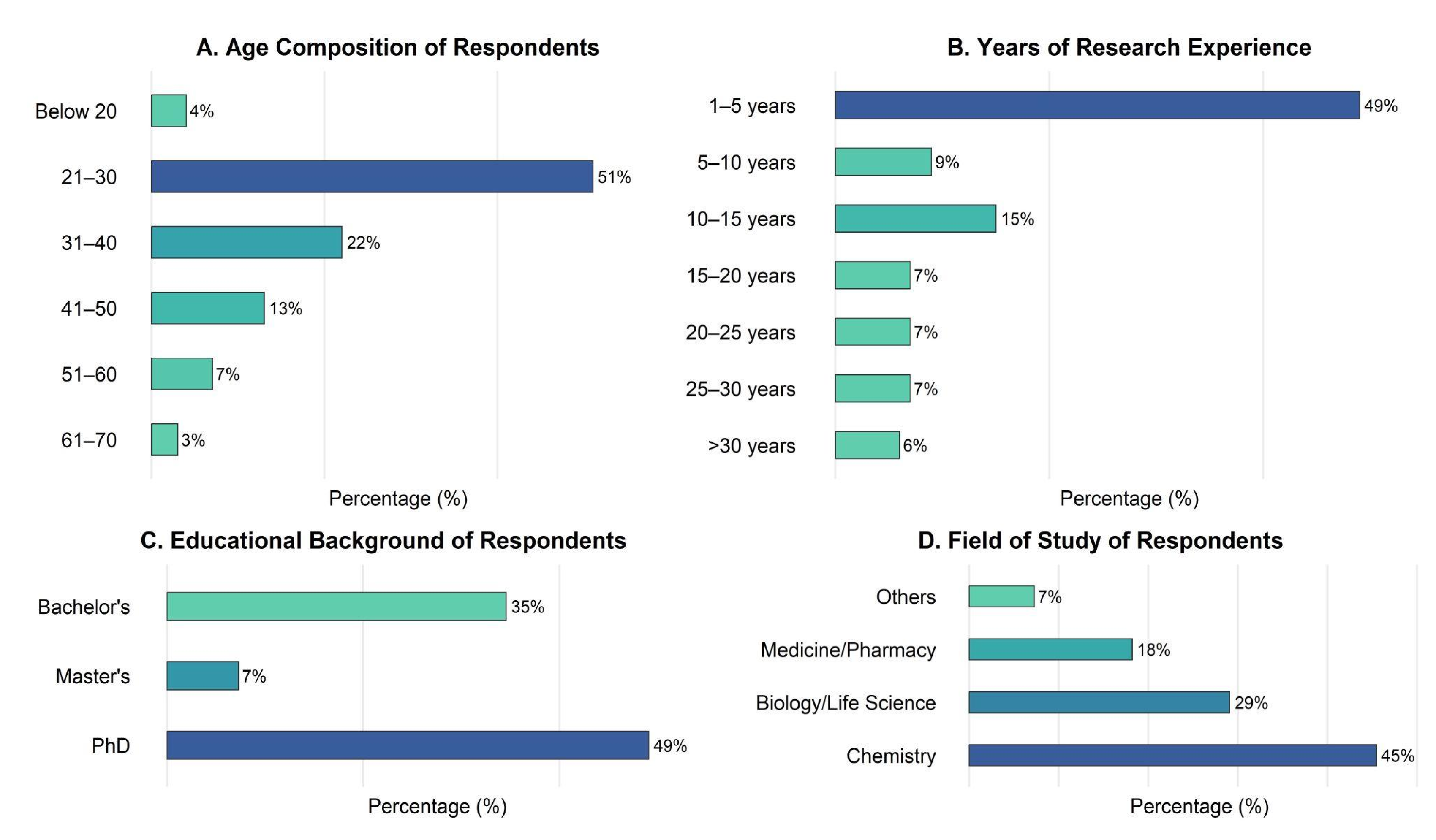

The pilot survey received a total of 55 responses. The respondents spanned a variety of demographic backgrounds and research levels (see Appendix B). Most participants (51%) were aged 21–30 (

Figure 2A); 49% were identified as early-career researchers with 1–5 years of experience (

Figure 2B). Nearly half held a PhD (49%) and 35% held a bachelor’s degree (

Figure 2C). A significant majority were based in Canada, with most respondents affiliated with academic institutions and engaged in life sciences, including chemistry and biology (

Figure 2D). The demographic distribution indicates that the sample predominantly reflected younger researchers affiliated with academic institutions.

Understanding and Perception of Open Science

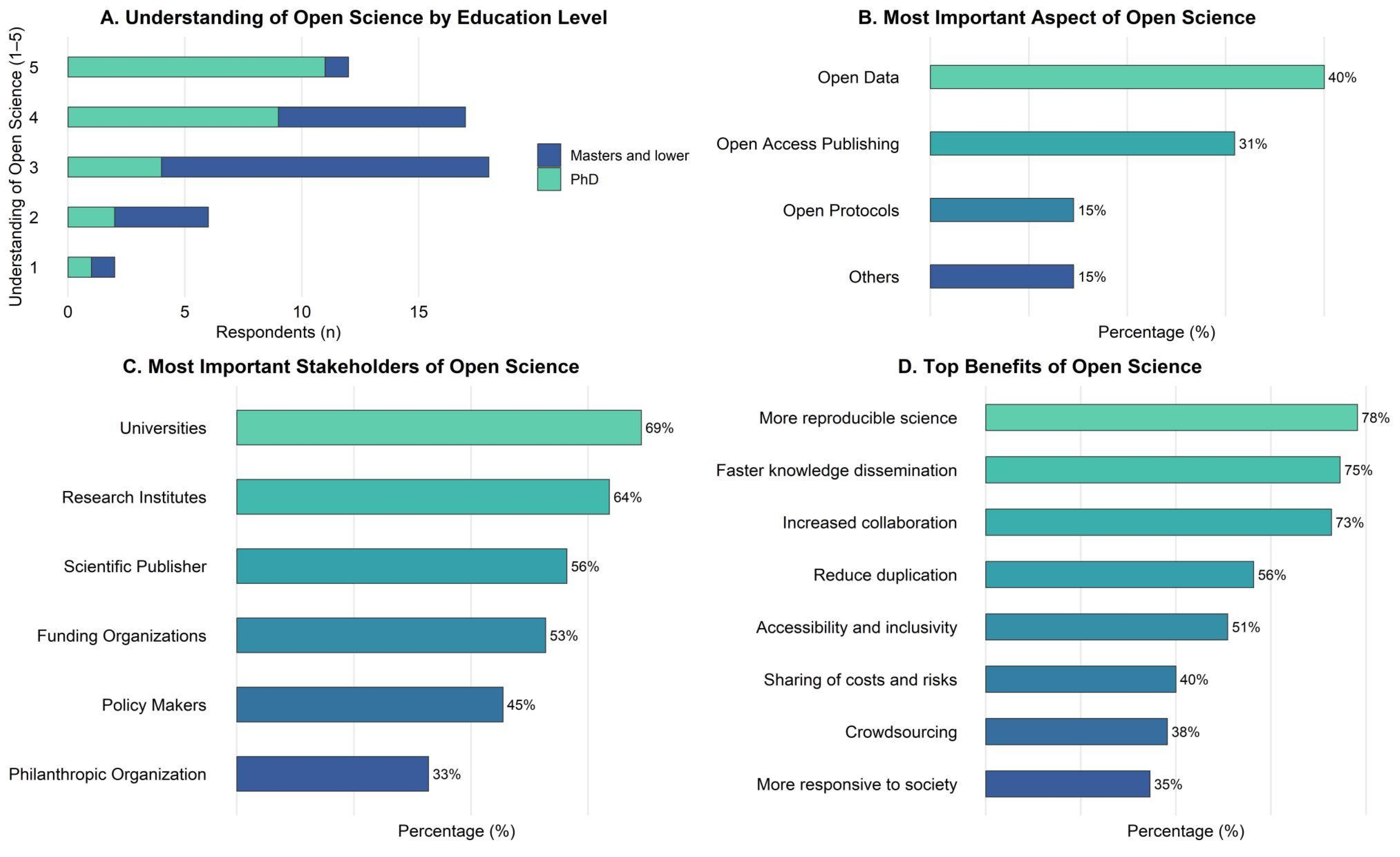

First, we examined participants’ understanding of Open Science and their perceptions of its importance in the research process (see Appendix C). Respondents reported a mean self-assessed understanding score of 3.6 on a 5-point scale, indicating moderate familiarity, with higher education associated with stronger knowledge (

Figure 3A). Open Data was rated most important (40%), followed by Open Access Publishing (31%) and Open Protocols (15%) (

Figure 3B). Universities (69%) and research institutes (64%) were identified as the most critical stakeholders, followed by scientific publishers (56%) and funding organizations (53%) (

Figure 3C). Key benefits included increased collaboration (80%), faster knowledge dissemination (73%), and improved reproducibility (71%) (

Figure 3D). These findings suggest that participants recognized both the value of Open Science and the central role of academic institutions in advancing it.

Open Science in Participant's Work

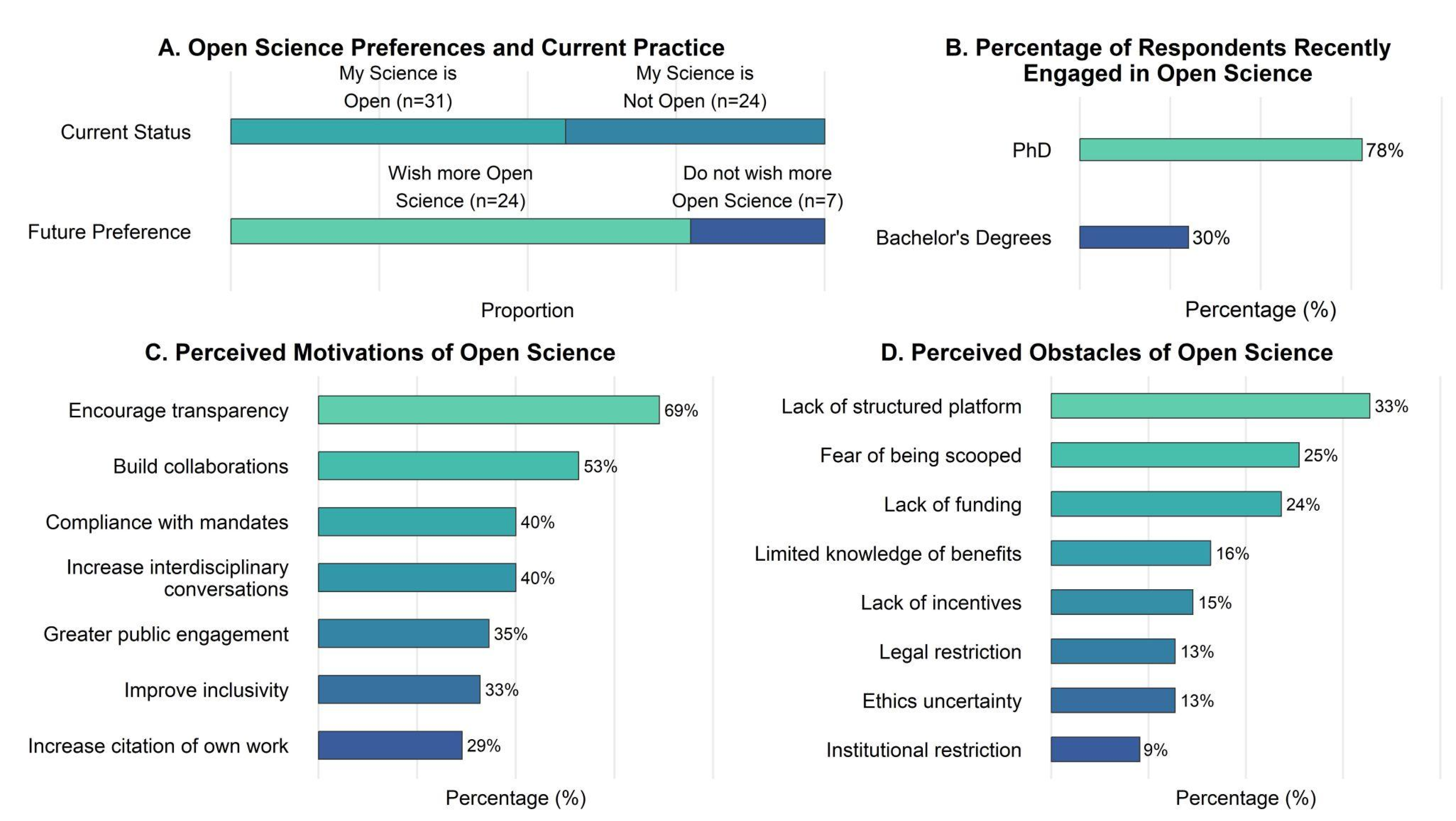

Next, we evaluated how researchers currently engage with Open Science, their perception of open research practices, and the motivations and barriers they face. Respondents generally viewed their research as moderately open: 44% rated openness at level 4 on a 5-point scale and 26% at level 3 (

Figure 4A). Most expressed a preference for greater openness, indicating barriers to implementation. Engagement was higher among PhD holders (78%) compared with bachelor’s degree respondents (30%) (

Figure 4B).

Motivations for participation included promoting transparency (69%), fostering collaboration (53%), and enabling interdisciplinary exchange (40%) (

Figure 4C). Early-career researchers often emphasized incentives linked to career development, while senior researchers highlighted broader contributions to science. Reported barriers included lack of sharing platforms (33%), fear of being scooped (26%), and limited funding (24%) (

Figure 4D). Institutional restrictions were more frequently cited by early-career researchers with bachelor’s degrees, whereas senior researchers pointed to inconsistent standards across disciplines. These results indicate that while openness is valued across career stages, structural and institutional limitations continue to constrain full participation of many researchers in Open Science research practices.

Knowledge and Participation in Sharing and Accessing Open Materials

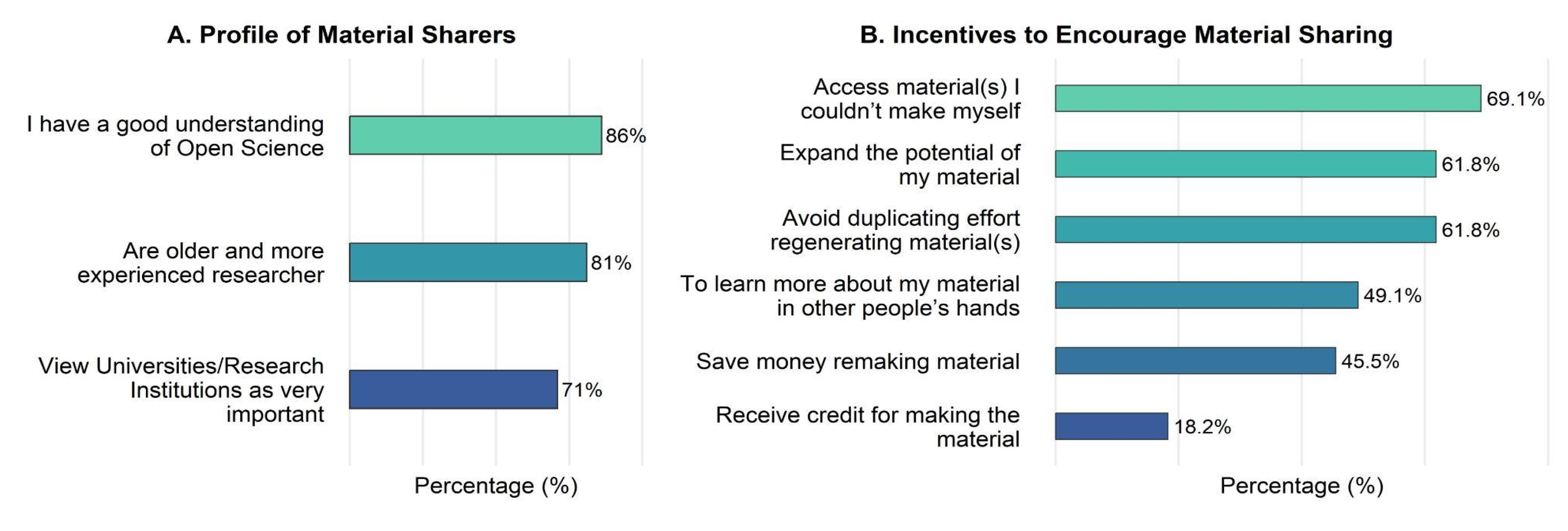

We then explored participants' direct experiences with sharing and accessing scientific materials through Open Science, aiming to identify gaps between willingness and actual participation. 38% of respondents reported sharing materials through Open Science repositories, while 62% had not. Among those that shared materials, 86% reported having accessed Open Materials generated by other researchers, which is much higher than the 35% from those who had not shared materials. Those who shared generally reported greater understanding of Open Science, longer research experience, and more often identified universities and research institutes as key stakeholders (

Figure 5A). Key incentives for material sharing included access to otherwise unavailable resources (69%), expanding knowledge and material possibilities, reducing duplication (62%), and lowering costs (46%) (

Figure 5B). Despite strong interest, respondents cited persistent challenges such as unclear citation practices and concerns over misuse or privacy. Younger researchers more frequently reported legal and institutional barriers, while senior researchers were less concerned by these potential issues. These findings highlight the need for training and consistent institutional support to strengthen adoption.

Sharing of Non-Renewable Materials

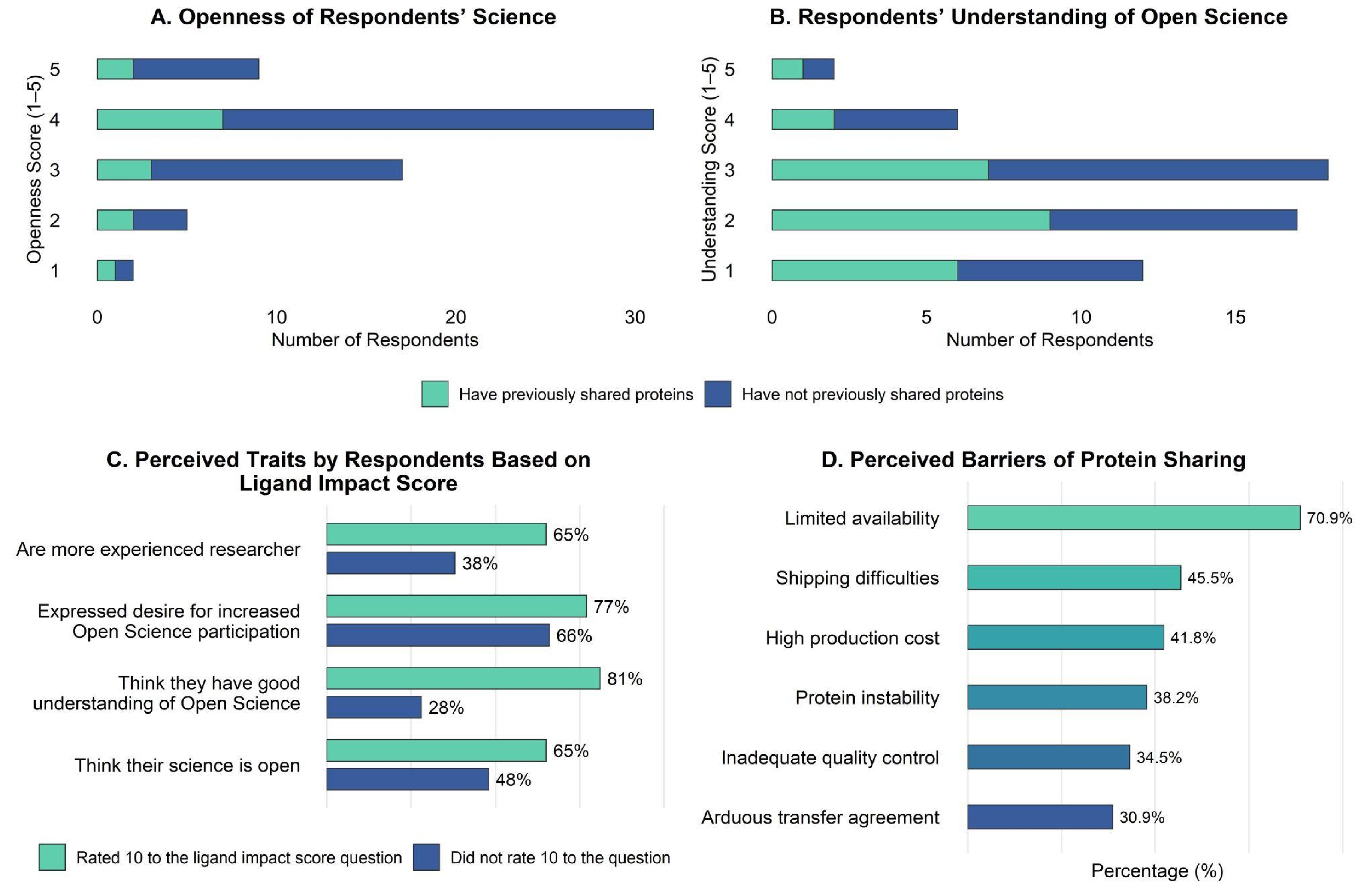

This part of the survey focused on the sharing and receiving of non-renewable research materials such as proteins, which is a key category in line with the Target 2035 initiative (see Appendix F). A majority (55%) had accessed open protein materials while fewer had shared (38%). Sharing was more common among respondents who perceived their research as open or reported higher understanding of Open Science, consistent with patterns observed in earlier sections of this study (

Figure 6A, 6B).

Participants were also asked to rate how ligand discovery for their proteins would impact their research. Responses were polarized, with scores of 1 and 10 most common. This polarization may also reflect a knowledge gap regarding the utility of chemical tools in biological research, even among researchers working directly with their proteins of interest. Those rating impact as 10 were more experienced, more engaged in Open Science, and more likely to have shared or received materials (

Figure 6C). Reported barriers to protein sharing included limited availability (71%), shipping challenges (46%), production cost (42%), and protein instability (38%), along with legal and institutional concerns (

Figure 6D). Finally, to better understand downstream capacity for collaboration, participants were also asked about their ability to validate ligands. Interestingly, 67% indicated their labs could perform such validation, representing underused capacity for Open Science participation.Those with validation capabilities were also more likely to share or access materials. These findings suggest that while protein sharing is limited, stronger engagement, perceived benefits, and available validation capacity present substantial untapped potential for advancing Open Science.

Reward System of Open Material

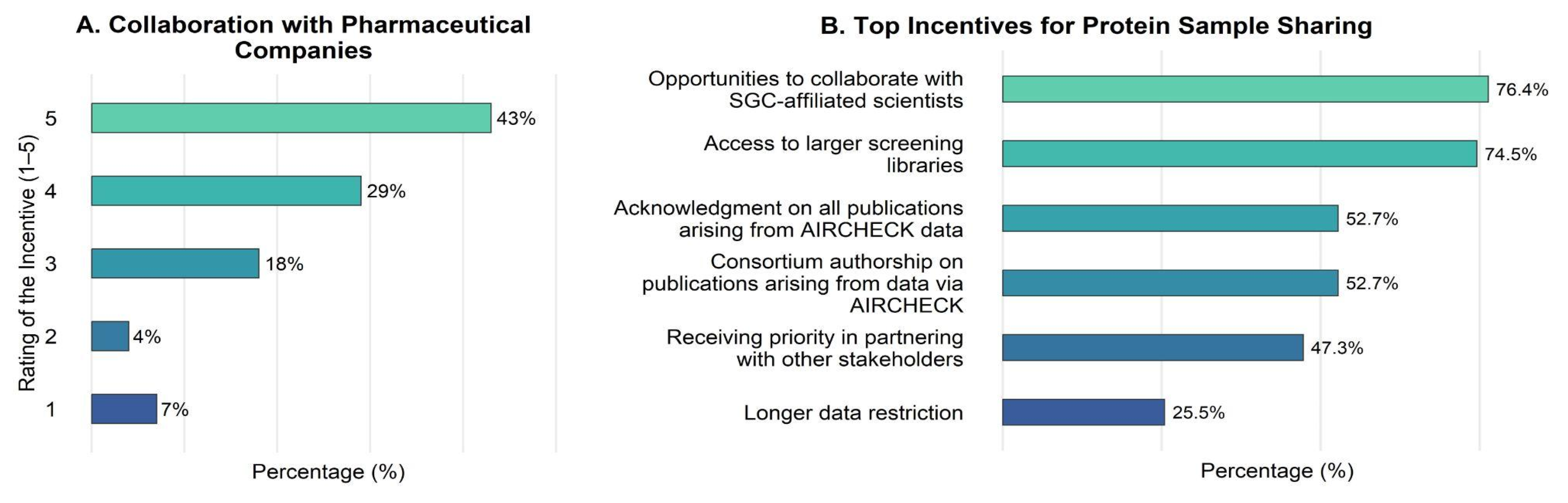

In this section, we examined potential reward systems and incentives for broader Open Science adoption, including exclusivity, industry collaboration, and institutional recognition (see Appendix G). Participants were generally receptive to learning about Open Material sharing. Views on a six-month restricted access period were mixed: some saw it as an incentive, while others felt it conflicted with Open Science values.

Collaboration with pharmaceutical companies was a strong motivator, especially for those who emphasized funder involvement (

Figure 7A). Other incentives included access to screening libraries, collaborative opportunities, publication recognition, and consortium authorship through the AIRCHECK database. (

Figure 7B) Many participants highlighted the importance of institutional support, particularly recognition of Open Science in hiring, promotion, and funding decisions. Suggested enablers included standardized attribution systems, clear collaboration agreements, and reliable sharing frameworks.

Discussion

This pilot study explored researchers’ opinions and attitudes toward Open Science with a focus on the sharing and use of Open Materials, particularly non-renewable biological resources. The survey examined barriers, incentives, and demographic factors that shape engagement, as well as the role of institutional structures and funding policies. While enthusiasm for openness was evident, practical, legal, and cultural barriers continued to limit participation. Although based on a small and exploratory sample, these findings highlight both the promise of Open Materials and several areas that warrant further attention.

Key obstacles included production costs, shipping logistics, material instability, and unclear legal frameworks, with early-career researchers especially concerned about intellectual property and recognition. At the same time, strong incentives emerged: reduced duplication, cost savings, access to otherwise unavailable resources, and new collaboration opportunities. Researchers who had shared materials were also more likely to benefit from accessing others’ resources, underscoring the reciprocal value of participation.

Non-renewable materials, such as proteins, revealed particular tensions. Willingness to share was linked to perceived downstream value (e.g., ligand discovery), but polarized responses suggest a need for better communication about the benefits of chemical tools. Importantly, many respondents reported capacity to validate ligands, indicating underused resources that could be mobilized through coordinated initiatives.

Institutional and funder recognition were repeatedly identified as critical enablers. Embedding Open Materials contributions into career evaluation, grant systems, and standardized sharing frameworks could normalize participation and lower barriers. Visible leadership and advocacy will also be essential to shift competitive research culture toward openness.

In summary, while barriers remain, this study suggests clear pathways to expand the sharing and use of Open Materials: targeted education, reliable infrastructure, and formal recognition systems. These steps will be crucial for the sustainability of community-driven initiatives such as Target 2035 and for embedding Open Materials as a standard practice in science.

Further Steps for Open Science

To translate this pilot study’s findings into action, we propose a phased plan that begins with low-barrier steps and builds toward structural reform.

Teach openness early: Include Open Materials in undergrad/grad training and use real-world examples of successful sharing.

Give credit that counts: Require citation of shared materials and recognize contributions in CVs, hiring, tenure, and promotions.

Make sharing easier: Provide institutional offices or staff to handle shipping, storage, and legal questions.

Cover the costs: Offer small grants or dedicated funding to support preparation, distribution, and transportation and storage of shared materials.

Simplify the rules: Use standardized, ready-to-go templates for legal agreements and interoperable repositories for deposits.

Use existing capacity: Connect labs with underused expertise (e.g., ligand validation) to Open Materials networks.

Build strong partnerships: Encourage joint initiatives between academia, industry, and consortia to expand sharing opportunities.

Show the benefits: Share success stories widely and encourage senior researchers and funders to advocate for Open Materials.

Further Research

Future work could examine long-term drivers and barriers of Open Science engagement through longitudinal studies and evaluate the effectiveness of policies and training. Special attention could be given to the role of mentorship, as well as issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Investigating whether underrepresented groups encounter distinct challenges will help ensure Open Science is equitable and globally impactful.

Bias and Potential Improvements

This pilot study has limitations. The sample was primarily Canadian, particularly from the University of Toronto, which may restrict generalizability. Self-selection bias is possible, as researchers already interested in Open Science may have been more inclined to participate. Self-reported data may also reflect social desirability. Broader, cross-disciplinary sampling and the use of complementary methods, such as interviews and analysis of repository usage, would improve reliability and robustness.

Acknowledgement

We wish to acknowledge the members of SGC for all the advice and contributions they made to the project and their dedication to Open Science. Specifically members of the Harding lab who provided feedback and support along the study. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. David Dubins and Dr. Tameshwar Ganesh for offering advice and resources in helping with the project.

References

- OPUS Project. Ways to reach open science. [cited 2025 Mar 27]. Available online: https://opusproject.eu/openscience-news/ways-to-reach-open-science/.

- Center for Open Science. What is open science? [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://www.cos.io/open-science.

- CERN. Open science elements. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://openscience.cern/OS-elements.

- Salazar Kämpf M, Riehle M, Ehrenthal JC, Blackwell SE, Möllmann A, Cwik J, et al. How to practice open science: a cookbook for clinical psychology research. PsyArXiv [preprint]. 2025 Jan 31. [CrossRef]

- Allen C, Mehler DMA. Open science challenges, benefits and tips in early career and beyond. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(5):e3000246. [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo L, Küngas R, Oras E, Köster K, Eenmaa H, Leijen Ä, et al. Data sharing practices and data availability upon request differ across scientific disciplines. Sci Data. 2021;8(1):192. [CrossRef]

- Borghi J. Supporting open data practices through good data management. Harv Data Sci Rev. 2022;4(1). [CrossRef]

- Edwards AM, Arrowsmith CH, Bountra C, Knapp S, Müller S, Willson TM, et al. Target 2035: A global initiative to expand the druggable proteome. ChemRxiv [Preprint]. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Addgene: mission [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. Available online: https://www.addgene.org/mission/.

- UK C org. Chemical Probes Portal. [cited 2025 Sep 19]. About us. Available online: https://www.chemicalprobes.org/info/about-us.

- Target 2035. Towards medicines for all. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://www.target2035.net/.

- Structural Genomics Consortium. Participate. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://www.thesgc.org/participate.

- Arrowsmith CH, Edwards AM, Bountra C, Knapp S, Willson TM, Müller S. Target 2035: a global open science initiative to expand the druggable proteome. Nat Rev Chem. 2025;9:559-61. [CrossRef]

- Impact | structural genomics consortium [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 6]. Available online: https://www.thesgc.org/index.php/about/impact.

- Farnham A, Kurz C, Öztürk MA, Solbiati M, Myllyntaus O, Meekes J, et al. Early career researchers want open science. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):221. [CrossRef]

- Center for Open Science. About. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://www.cos.io/about.

- UNESCO. Open science. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/open-science?hub=686.

- Structural Genomics Consortium. Home. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://www.thesgc.org/.

- Casimo K. Teaching and training with open science: from classroom teaching tool to professional development. Neuroscience. 2023;525:6–12. [CrossRef]

- Lattu A, Cai Y. Institutional logics in the open science practices of university–industry research collaboration. Sci Public Policy. 2023;50(5):905–916. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Horizon Europe. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe_en.

- National Science Foundation. NSF Public Access Initiative. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/public-access.

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The Gates Foundation’s open access policy. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://openaccess.gatesfoundation.org/the-bill-melinda-gates-foundations-open-access-policy/.

- Fang FC, Casadevall A. Competitive science: is competition ruining science? Infect Immun. 2015;83(4):1229–1233. [CrossRef]

- Waaijer CJF, Teelken C, Wouters PF, van der Weijden ICM. Competition in science: links between publication pressure, grant pressure and the academic job market. High Educ Policy. 2018;31(2):225–243. [CrossRef]

- Anderson MS, Ronning EA, De Vries R, Martinson BC. The perverse effects of competition on scientists’ work and relationships. Sci Eng Ethics. 2007;13(4):437–461. [CrossRef]

- Center for Open Science. The Open Science Framework. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available online: https://www.cos.io/products/osf.

Figure 1.

The map illustrates the international network of laboratories and institutions that contributed proteins to the SGC during the pilot phase of a large-scale screening project conducted over six months. Circle size is proportional to the number of contributing labs or institutes in each region.

Figure 1.

The map illustrates the international network of laboratories and institutions that contributed proteins to the SGC during the pilot phase of a large-scale screening project conducted over six months. Circle size is proportional to the number of contributing labs or institutes in each region.

Figure 2.

Respondent demographics. (A) The majority of respondents were in the age category of 21–30 years old. (B) The majority of respondents were new researchers with 1–5 years of research experience. (C) Most respondents held a PhD degree, followed by a Bachelor’s degree. (D) The majority of respondents were from Chemistry, followed by Biology/Life Science and Medicine/Pharmacy fields.

Figure 2.

Respondent demographics. (A) The majority of respondents were in the age category of 21–30 years old. (B) The majority of respondents were new researchers with 1–5 years of research experience. (C) Most respondents held a PhD degree, followed by a Bachelor’s degree. (D) The majority of respondents were from Chemistry, followed by Biology/Life Science and Medicine/Pharmacy fields.

Figure 3.

Perceptions of Open Science among respondents. (A) Distribution of understanding of Open Science (scores 1–5), segmented by education level (Master’s and lower vs. PhD). (B) First-choice ranking of the most important aspects of Open Science, with Open Data rated highest. (C) Percentage of respondents who rated each stakeholder group as “very important” for advancing Open Science. (D) Percentage of respondents who rated each listed benefit of Open Science as “greatly beneficial.”.

Figure 3.

Perceptions of Open Science among respondents. (A) Distribution of understanding of Open Science (scores 1–5), segmented by education level (Master’s and lower vs. PhD). (B) First-choice ranking of the most important aspects of Open Science, with Open Data rated highest. (C) Percentage of respondents who rated each stakeholder group as “very important” for advancing Open Science. (D) Percentage of respondents who rated each listed benefit of Open Science as “greatly beneficial.”.

Figure 4.

Open Science practices and preferences. (A) Of 55 respondents, 44% rated their research as less open (Likert 1–3) and 56% as open (Likert 4–5). Among the latter, 77% preferred greater openness. (B) Engagement in Open Science was reported by 78% of PhD respondents and 30% of bachelor’s degree holders. (C) Key motivations included transparency (69%), collaborations (53%), and compliance with mandates (40%). (D) Common obstacles included lack of a structured platform (33%), fear of being scooped (25%), and limited funding (24%).

Figure 4.

Open Science practices and preferences. (A) Of 55 respondents, 44% rated their research as less open (Likert 1–3) and 56% as open (Likert 4–5). Among the latter, 77% preferred greater openness. (B) Engagement in Open Science was reported by 78% of PhD respondents and 30% of bachelor’s degree holders. (C) Key motivations included transparency (69%), collaborations (53%), and compliance with mandates (40%). (D) Common obstacles included lack of a structured platform (33%), fear of being scooped (25%), and limited funding (24%).

Figure 5.

Incentives for material sharing and respondent characteristics. (A) Profile of 21 respondents who had shared materials: they reported greater understanding of Open Science, were older and more experienced, and 71% viewed universities or research institutes as key stakeholders. (B) Reported incentives for participating in Open Material sharing and access.

Figure 5.

Incentives for material sharing and respondent characteristics. (A) Profile of 21 respondents who had shared materials: they reported greater understanding of Open Science, were older and more experienced, and 71% viewed universities or research institutes as key stakeholders. (B) Reported incentives for participating in Open Material sharing and access.

Figure 6.

Protein sharing in relation to openness, understanding, and ligand-impact score. (A) Respondents with greater understanding of Open Science were more likely to have shared proteins. (B) Among those rating their research as more open, protein sharing was more frequent at understanding scores ≤4, with score 5 as an outlier. (C) Respondents who rated ligand discovery as highly impactful (score = 10) also reported greater willingness to participate in Open Science, higher understanding, greater openness, and more research experience. (D) Common barriers to protein sharing included limited availability, shipping difficulties, and high production cost.

Figure 6.

Protein sharing in relation to openness, understanding, and ligand-impact score. (A) Respondents with greater understanding of Open Science were more likely to have shared proteins. (B) Among those rating their research as more open, protein sharing was more frequent at understanding scores ≤4, with score 5 as an outlier. (C) Respondents who rated ligand discovery as highly impactful (score = 10) also reported greater willingness to participate in Open Science, higher understanding, greater openness, and more research experience. (D) Common barriers to protein sharing included limited availability, shipping difficulties, and high production cost.

Figure 7.

Incentives for material sharing. (A) Respondents who valued funding organizations as key stakeholders also identified pharmaceutical company collaboration as a strong incentive. (B) Top incentives included collaboration with SGC scientists, access to larger screening libraries, publication recognition, and priority in partnering with stakeholders.

Figure 7.

Incentives for material sharing. (A) Respondents who valued funding organizations as key stakeholders also identified pharmaceutical company collaboration as a strong incentive. (B) Top incentives included collaboration with SGC scientists, access to larger screening libraries, publication recognition, and priority in partnering with stakeholders.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).