Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

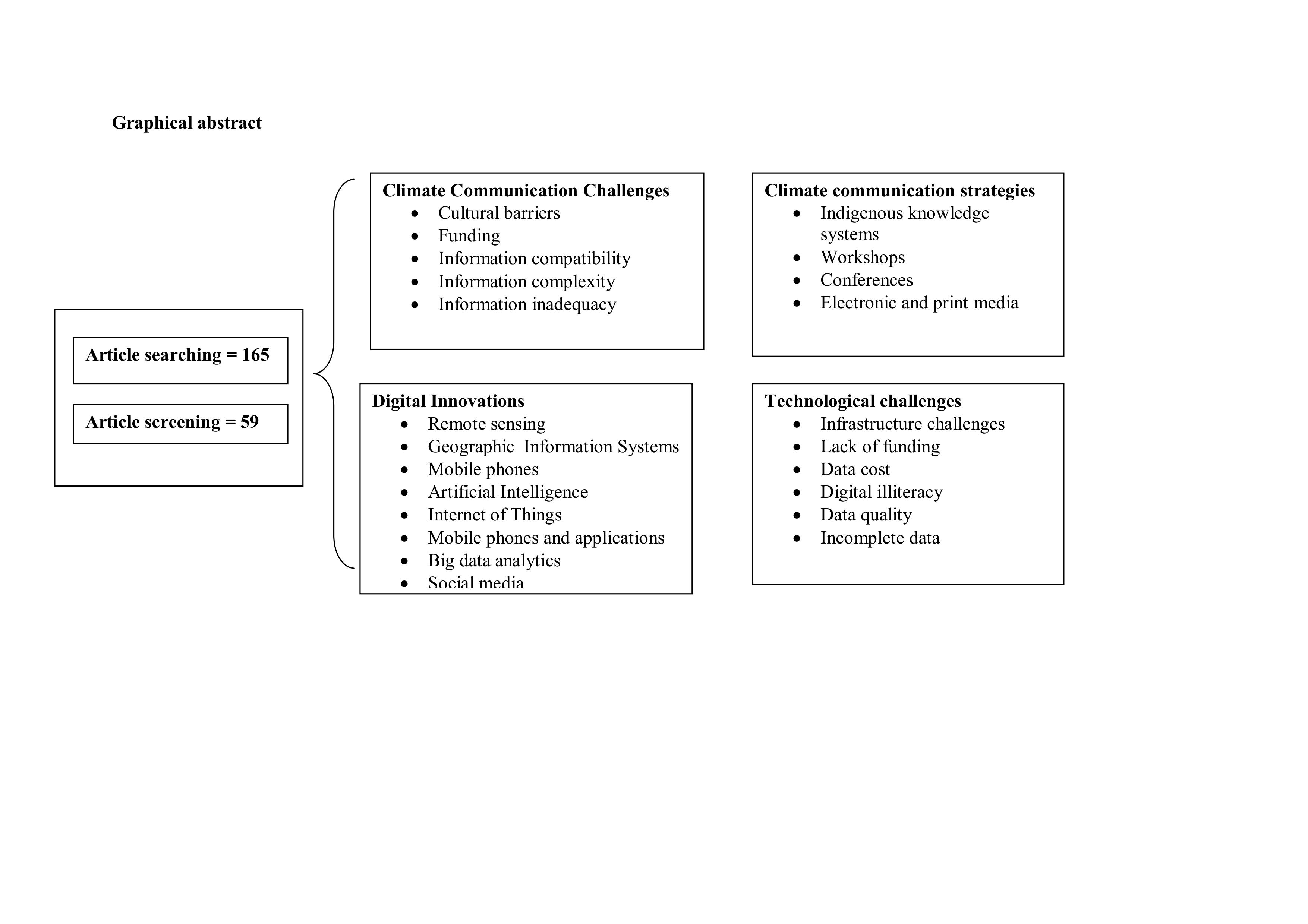

1. Background

2. Objectives

- (i)

- Identify challenges in climate communication in Southern Africa

- (ii)

- Assess the strategies of climate communication in southern Africa

- (iii)

- Examine digital innovations in climate change communication in Southern Africa

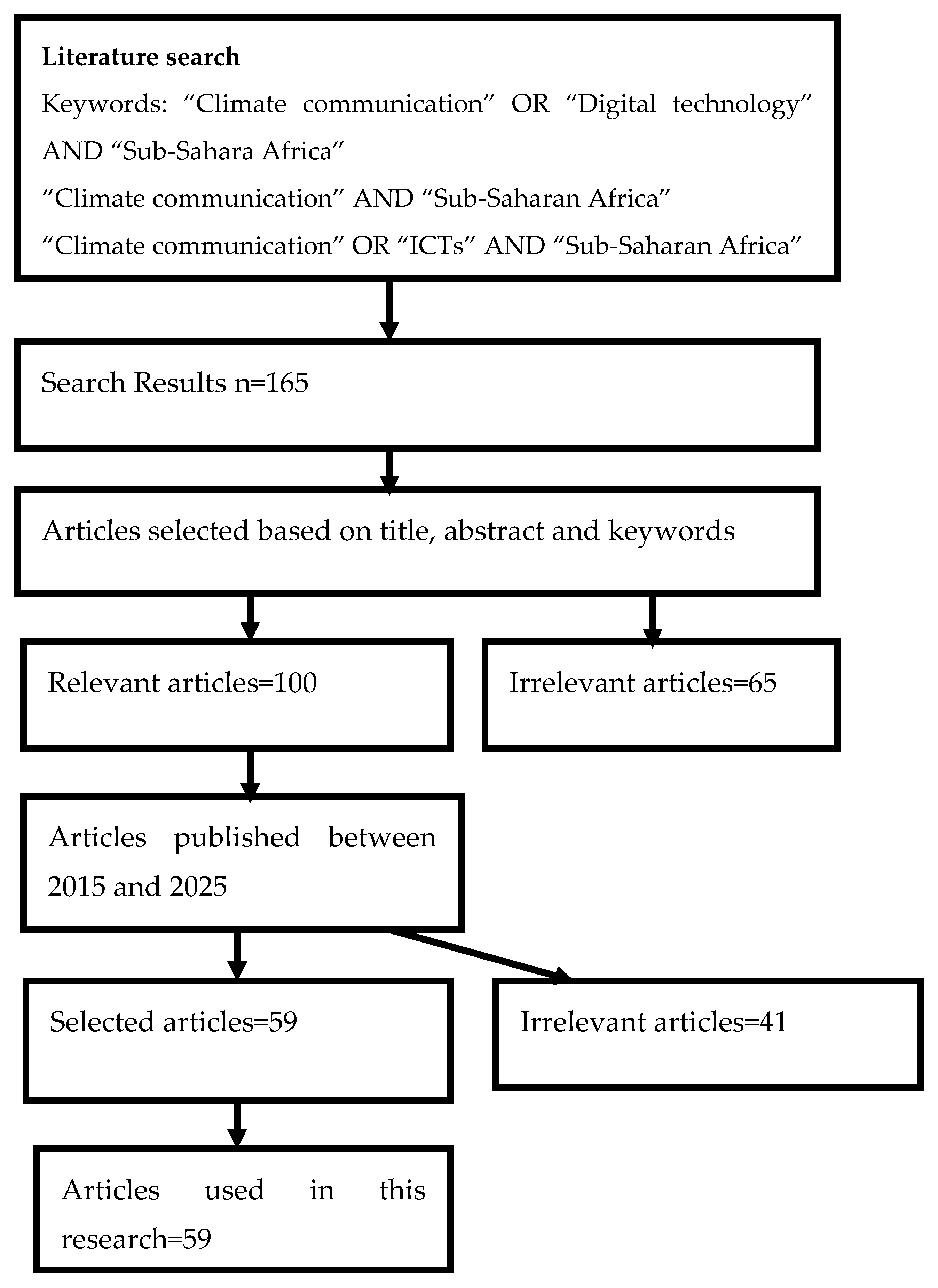

3. Methodology

3.1. Literature Sources

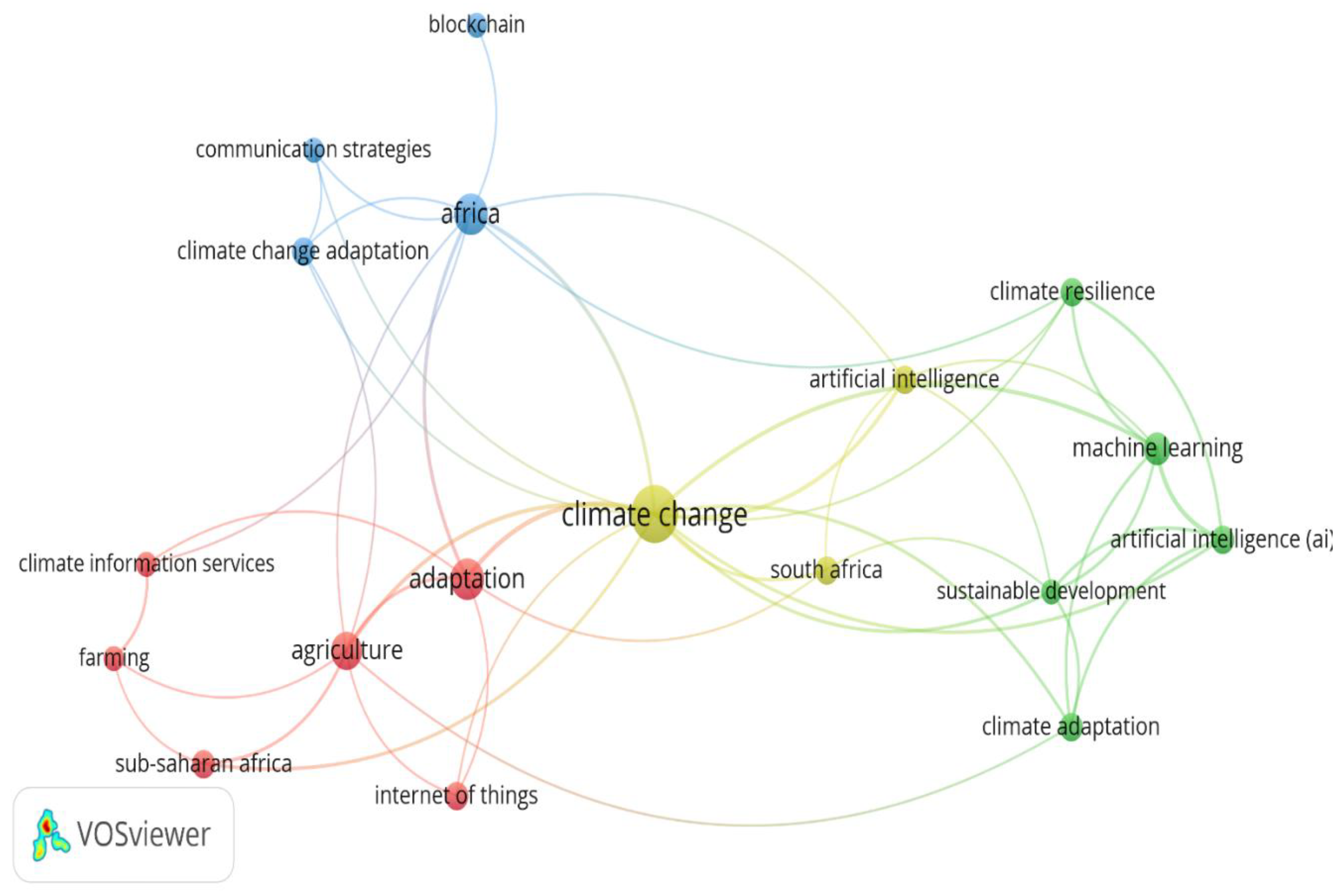

3.2. Co-Citation and Occurrence of Keywords

4. Findings and Discussions

4.1. Challenges in Climate Communication

4.2. Strategies of Climate Communication in Southern Africa

4.3. Digital Innovations in Climate Change Communication

- (a)

- Remote sensing technologies, for example, drones, satellites, satellite- receiving stations in Zimbabwe, South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, and Mozambique where they have been used for Examining environmental variables for climate resilience strategies Climate vulnerability assessments Climate impact assessment Veld fire monitoring

- (b)

- Mobile phones in Malawi, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, Angola, Lesotho, and Eswatini where they have been used for Climate and weather information dissemination Early warning Agricultural information dissemination

- (c)

- Machine learning in Malawi, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, Angola, Lesotho, and Eswatini where they have been used for Climate projections Analyzing satellite imagery to detect changes in land use and vegetation

- (d)

- Deep learning in Malawi, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Angola, Mozambique, Lesotho and, Eswatini where they have been used for Monitoring deforestation, guiding land-use planning.

- (e)

- The Internet of Things in Malawi, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, Angola, Lesotho, and Eswatini where they have been used for Data collection, communication, processing, and actionable intelligence by farmers, agricultural extension officers, climate disaster experts, and other stakeholders.

4.4. Technological Challenges in Climate Communication

5. Conclusions

Recommendations

References

- Adebayo, A., Victor, P. O., Oyedeji, O. C., Adebayo, A. V. and Mubarak, A. M. (2024). Climate change effect in nigeria mitigation, adaptation, strategies and way forward in the world of Internet of Things. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology. 9(4). [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, R.; Forouheshfar, Y.; Moghadas, O. Enhancing system resilience to climate change through artificial intelligence: a systematic literature review. Front. Clim. 2025, 7, 1585331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, O. J.; Izuchukwu, A.; Abiola, D. S. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Climate Change Mitigation in Africa: A Sustainable Approach. World Journal of Innovation and Modern Technology ISSN 2682-5910.. 2025, 9(6). [Google Scholar]

- Brummer, U. (2024). Blockchain technology for agriculture traceability systems in South Africa. Master of management thesis. Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town.

- Carr, E. R.; Goble, R.; Rosko, H. M.; Vaughan, C.; Hansen, J. Identifying climate information services users and their needs in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review and learning agenda. Climate and Development 2020, 12(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapungu, L., Togo, M., and Raimundo, I. (2024). Prospects and Challenges for Adopting Artificial Intelligence and Digital Tools in Climate Resilience in Rural Southern Africa: A Systematic Review. In Editors Climate Change Resilience in Rural Southern Africa: Dynamics, Prospects and Challenges. Springer.

- Chari, T. Rethinking climate change communication strategies in Africa: The case for indigenous media. Indilinga-African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems 2016, 15(2). [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Hassanzadeh, P.; Pasha, S. Predicting clustered weather patterns: a test case for applications of convolutional neural networks to spatio-temporal climate data. Sci Rep 2020, 10(1), 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavula, P.; Kayusi, F. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Disseminating Climate Information Services in Africa. LatIA 2025, 3, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavula, P.; Kayusi, F.; Juma, L. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Enhancing Wheat Yield Resilience Amidst Climate Change in Sub-Saharan Africa. LatIA 2024, 2024; 2, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimanga, K.; Kanja, K. The Role of ICTs in Climate Change Adaptation: A Case of Small Scale Farmers in Chinsali District. Mathematics and Computer Science 2020, 5(6), 103–109. http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/mcs. [CrossRef]

- Chizema, T. R., Dlamini, P., Van Greunen, D., and Msomi, S. (2024). The Perceived Influence of Internet of Things on Precision Agriculture for Small-Scale Farming. IST-Africa 2024 Conference Proceedings Miriam Cunningham and Paul Cunningham (Eds)IST-Africa Institute and IIMC, 2024, ISBN: 978-1-905824-72-4.

- Choi, C.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, D.; Bae, Y.; Kim, H. S. Development of heavy rain damage prediction model using machine learning based on big data. In Research article. Advances in meteorology; Hindawi, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, J.; Marulanda, G.; Bello, A.; Reneses, J. Air temperature forecasting using machine learning techniques: a review. Energies 2020, 13(16), 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowls, J.; Tsamados, A.; ·Taddeo, M.; Floridi, L. The AI gambit: leveraging artificial intelligence to combat climate change—opportunities, challenges, and recommendations. AI & SOCIETY 2023, 38, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, V.; Cox, P. M.; Flato, G. M.; Gleckler, P. J.; Abramowitz, G.; Caldwell, P. Taking climate model evaluation to the next level. Nat Clim Chang. 2019, 9(2), 102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W. L; Lütz, J. M.; Totin, E.; Ayal, D.; Mendy, E. Obstacles to implementing indigenous knowledge in climate change adaptation in Africa. Journal of Environmental Management 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, W. L.; Gbaguidi, G. J. Using artificial intelligence in support of climate change adaptation Africa: potentials and risks. In Humanities and Social Sciences Communications; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, D. J.; Christensen, H.M.; Subramanian, A.C.; Monahan, A.H. Machine learning for stochastic parameterization: generative adversarial networks in the Lorenz ’96 model. J Adv Model Earth Syst 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, Y.G.; Kim, J.H.; Luo, J.J. Deep learning for multi-year ENSO forecasts. Nature 2019, 573(7775), 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntingford, C.; Jeffers, E.S.; Bonsall, M. B.; Christensen, H.M.; Lees, T.; Yang, H. Machine learning and artificial intelligence to aid climate change research and preparedness. Environ Res Lett 2019, 14(12), 124007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ise, T. and Oba, Y. (2019). Forecasting climatic trends using neural networks: an experimental study using global historical data. Front Robot AI. [CrossRef]

- Jaafari, A., Zenner, E.K., Panahi, M., and Shahabi, H. (2019). Hybrid artificial intelligence models based on a neuro-fuzzy system and metaheuristic optimization algorithms for spatial prediction of wildfire probability. Agric for Meteorol 266–267(March):198–207. [CrossRef]

- Kachali, R. (2020). Climate Change, Social Media And The African Youth: A Malawian Case Study. Master’s Thesis, Strategic Communication. School of Humanities, Education & Social Sciences Dissertation. UREBRO UNIVERSITET.

- Kassam, A.; Friedrich, T; Derpsch, R. Global spread of conservation agriculture. Int J Environ Stud. 2019, 76(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibu, S.; Ngowi, E. Effectiveness of climate information services in Sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural sector: a systematic review of what works, what doesn’t work, and why. Front. Clim. 2025, 7, 1616691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Panahi, M.; Golkarian, A.; Keesstra, S.D.; Saco, P.M.; Bui, D.T; Lee, S. Convolutional neural network approach for spatial prediction of flood hazard at national scale of Iran. J. Hydrol. 2020, 591 (August), 125552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraondo, P. R.; Renzullo, L. J.; Van Dijk, A. I. J. M.; Inza, I.; Lozano, J. A. Optimization of deep learning precipitation models using categorical binary metrics. J Adv Model Earth Syst 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokeswari, K. A study of the use of ICT among rural farmers. International Journal of Communication Research 2016, 6(3). [Google Scholar]

- Makuvaro, V.; Chitata, T.; Tanyanyiwa, E.; Zirebwe, S. Challenges and Opportunities in Communicating Weather and Climate Information to Rural Farming Communities in Central Zimbabwe. Weather, Climate and Society 2023, 15(1), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matandirotya, N. R.; Filho, W. L.; Mahed, G.; Dinis, M. A. P.; Mathe, P. Local knowledge of climate change adaptation strategies from the vhaVenda and baTonga communities living in the Limpopo and Zambezi River Basins, Southern Afric. Inland Waters 2024, 14(3), 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawila, C. (2024). Framing of climate change in South Africa: An analysis of content in News24 and TikTok. master’s degree in journalism and media studies thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa.

- Mayoyo, A,, Chapoto, A., Matchaya, G., Aheeyar, M., Chiwunze, G., Ebrahim, G., Ajayi, O.C., Afun-Ogidan, O., Fakudze, B. and Kasoma-Pele, W. (2023). Digital Climate Adaptation in Agriculture Profile for Zimbabwe. Internatinal Water Management Institute, Global Centre on Adaptation, and the African Development Bank. Colombo, Rotterdam and Abidjan.

- Mbuvha, R., Yaakoubi, Y., Bagiliko, J., Potes, S. H., Nammouchi, A. and Amrouche, S. (2024). Leveraging AI for Climate Resilience in Africa: Challenges, Opportunities, and the Need for Collaboration. (pp. 1-5). SSRN. [CrossRef]

- McGahey, D. J.; Lumosi, C. K. Climate Change Communication For Adaptation: Mapping Communication Pathways In Semi-Arid Regions To Identify Research Priorities. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 20(1) 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muchunku, I. G.; Ageyo, J. New Media and Climate Change Communication: An Assessment of Utilization of New Media Platforms in Publication of Glocalized Climate Change Information by East Africa’s Science Journalists. International Journal of Academic Research in Environment & Geography 2022, 9(1), 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mukarumbwa, P.; Taruvinga, A. Landrace and GM maize cultivars’ selection choices among rural farming households in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. GM Crops Food 2023, 14(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muteba, T. (2020). Climate Communication for Adaptation Planning In the Tourism Sector In Livingstone, Zambia. Masters of Science in Environmental and Natural Resource Management Dissertation. The University of Zambia. Zambia.

- Naidoo, G. M. The Potential of Artificial Intelligence in South African Rural Development. In Special Edition of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences; University Zululand, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ngulube, P. Leveraging information and communication technologies for sustainable agriculture and environmental protection among smallholder farmers in tropical Africa. In Discover Environment; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nigussie, E., Olwal, T. O., Lemma, A., Mekuria, F. and Peterson, B. (2020). IoT Architecture for Enhancing Rural Societal Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. The 11th International Conference on Emerging Ubiquitous Systems and Pervasive Networks (EUSPN 2020) November 2-5, 2020, Madeira, Portugal. Procedia Computer Science 177 (2020): 338–344.

- Nkambule, T. B; Agholor, A. I. Information Communication Technology as a Tool for Agricultural Transformation and Development in South Africa. A review. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry (TOJQI) 2021, 12(7), 8658–8677. [Google Scholar]

- Odoom, D. and Fosu, M. (2023). Towards Promoting Climate Change Communication for Improved Adaptation in Africa: A Ghanaian Perspective. Journal of Policy and Development Studies (JPDS).14(1), ISSN(p) 0189-5958 ISSN (e) 2814-1091.

- Olatade, D, P. and Mogaji, R,I. (2025). Towards Inclusive Climate Solutions: Merging Indigenous African Knowledge and Artificial Intelligence in Rural Communities. JEPSD 1(1), 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Onoja, A.O., Emodi, A.I., Chagwiza, C. and Tagwi, A. (2022). Utilizing ICTs in Climate Change Resilience Building Along Agricultural Value Chains in Sub-Sahara Africa. Nigerian Agricultural Policy Research Journal (NAPReJ). 10, Special Issue.

- Onyancha, O. B; Onyango, E. A. Information And Communication Technologies For Agriculture (ICT4ag) In Sub-Saharan Africa: A Bibliometrics Perspective Based On Web Of Science Data, 1991–2018. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev 2020, 20(5), 16343–16370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, M.; Jaafari, A.; Shirzadi, A.; Shahabi, H.; Rahmati, O.; Omidvar, E.; Lee, S.; Bui, D.T. Deep learning neural networks for spatially explicit prediction of flash flood probability. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12(3), 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, A.; Chipeta, G. T.; Chawinga, W. D. Information needs and barriers of rural smallholder farmers in developing countries: A case study of rural smallholder farmers in Malawi. Information Development 2019, 35(3), 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policy Makers. Sustainability 14(3870). [CrossRef]

- Rasp, S.; Pritchard, M.S.; Gentine, P. Deep learning to represent subgrid processes in climate models. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018, 115(39), 9684–9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Benson, V.; Blunk, J.; Camps-Valls, G.; Creutzig, F.; Fearnley, C. J.; Han, B.; Kornhuber, K.; Rahaman, N.; Schölkopf, B.; Tárraga, J. M.; Vinuesa, R.; Dall, K.; Denzler, J.; Frank, D.; Martini, G.; Nganga, N.; Maddix, D. C.; Weldemariam, K. Early warning of complex climate risk with integrated artificial intelligence. Nature Communications 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolnick, D.; Donti, P. L.; Kaack, L. H.; Kochanski, K.; Lacoste, A.; Sankaran, K.; Ross, A. S.; Milojevic-Dupont, N.; Jaques, N.; Waldman-Brown, A. Tackling climate change with machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2022, 55(2), 1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansa-Otim, J.; Nsabagwa, M.; Mwesigwa, A.; Faith, B.; Owoseni, M.; Osuolale, O.; Mboma, D.; Khemis, B.; Albino, P.; Ansah, S. O. An Assessment of the Effectiveness of Weather Information Dissemination among Farmers and Policy Makers. Sustainability 2022, 14(3870). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarku, R.; Addi, F.; Attoh, E. M. N. A.N. New Information and Communication Technologies for climate services: Evidence from farmers in Ada East District, Ghana. Climate Services 2025, 37, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimhanda, M. N; Vivian, B. Media coverage of climate change in Namibia and South Africa: A comparative study of newspaper reports from October 2018 to April 2019. Namibian Journal of Environment 2022, 6 A, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, P.; Liu, E.; He, W.; Sun, Z.; Dong, W.; Yan, C. Effect of no-tillage with straw mulch and conventional tillage on soil organic carbon pools in Northern China. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2018, 64(3), 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibandze, P.; Kalumba, A. M.; Afuye, G. A.; Kganyago, M. Integrating remote sensing data and fully connected CNN for flood probability and risk assessment in the Port St Johns coastal town, South Africa. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2025, 39, 101630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeker, I., Lusinga, S., and Chigona, W. (2021). Readiness of the South African Agricultural Sector to Implement IOT. Proceedings of the 1st Virtual Conference on Implications of Information and Digital Technologies for Development, 2021.

- Sønderby, C. K., Espeholt, L., Heek, J., Dehghani, M., Oliver, A., Salimans, T., Agrawal, S., Hickey, J. and Kalchbrenner, N. (2020). MetNet: a neural weather model for precipitation forecasting. http:// arxiv. org/abs/2003.12140.

- Stankovic, M.; Neftenov, N.; Gupta, R. Use of Digital Tools in Fighting Climate Change: A Review of Best Practices. In ResearchGate; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tella, D. The Use of Social Media in Communicating Environmental Governance: A Review Of Two Social Media Platforms In South Africa And Kenya. Journal of Environment and Politics in Africa 2024, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, S.; Torresan, S.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Critto, A.; Zebisch, M.; Marcomini, A. Multi-risk assessment in mountain regions: A review of modelling approaches for climate change adaptation. J Environ Manage 2019, 232, 759–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, T. M.; Lan, D. H.; Tan, T. L. Bridging The Gap: Effective Communication Strategies for Climate Change Adaptation in Rural Communities. Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences 2024, 22(2), 1039–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, K. L., Bouchet, P, J., Caley, M. J., Mengersen, K., Randin, C. F. and , Parnell, S. (2018). Outstanding challenges in the transferability of ecological models. Trends Ecol 33(10), 790–802. [CrossRef]

- Yohannis, M., Wausi, A. Waema, T and Hutchinson, M. (2019). The Role of ICT Tools in the Access of Climate Information by Rural Communities. Journal of Sustainability, Environment and Peace 1(2), 32–38.

- Zheng, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, R. H.; Liu, B. Purely satellite data-driven deep learning forecast of complicated tropical instability waves. Sci Adv 2020, 6(29), 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zougmoré, R. B.; Partey, S. T. Gender Perspectives of ICT Utilization in Agriculture and Climate Response in West Africa: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14(12240). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Theme | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Nigussie et al. (2020) | Irrigation management. | SSA |

| Nigussie et al. (2020) | IoT architecture. | SSA |

| Sibandze et al. (2025) | Remote sensing for flood probability. | South Africa |

| Appiah et al. (2025) | Social media for climate communication. | SSA |

| Sarku et al. (2025) | ICT services for climate communication. | Ghana |

| Bahta (2021) | Social networks. | South Africa |

| Mayoyo et al. (2023) | Digital climate adaptation. | Zimbabwe |

| Olatade and Mogaji (2025) | IK and AI for climate change. | Africa |

| Chapungu et al. (2021) | AI and ICTs for climate resilience | SSA |

| Filho et al. (2024) | Implementing IK in climate adaptation. | Africa |

| Soeker et al. (2021) | Readiness to implement IoT. | South Africa |

| Masinde et al. (2012) | ICT for weather forecasting. | SSA |

| Bakare (2020) | ICT and climate smart agriculture. | South Africa |

| Odoom et al. (2023) | Climate change communication. | Ghana |

| Ojonimi et al. (2022) | ICT for climate resilience | SSA |

| Tella., (2024) | Social media. | Kenya |

| Kiambi (2025) | ICT and agriculture | Kenya |

| Bosch (2012) | Blogging and Tweeting in climate change. | South Africa |

| McGahey and Lumosi (2018) | Climate change communication. | Kenya |

| Agbehadji et al. (2024) | Climate risk resilience and early warning systems. | Southern Africa |

| Chavula and Kayusi (2025) | AI in climate communication | Africa |

| Duruigbo (2013) | ICT strategies for climate change | SSA |

| Hansen et al. (2019) | Climate change services for farmers | Africa |

| Mofolo and Kagarura (2012) | IoT in sustainable rural development | South Africa |

| Carr et al. (2020) | Climate information services in SSA | SSA |

| Adebayo et al. (2024) | Climate change effectiveness in Nigeria (IoT) | Nigeria |

| Nkambule and Agholar (2025) | ICT for agricultural transformation in South Africa | South Africa |

| Chizema et al. (2024) | IoT for precision agriculture | Africa |

| Chavula et al. (2024) | AI and wheat yield resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa. | SSA |

| Matandirotya et al. (2024) | Local knowledge for climate adaptation | South Africa |

| Mwalukasa (2012) | Agricultural information services for climate change. | Tanzania |

| Muchunku and Ageyo (2022) | New media and climate change. | East Africa |

| Muteba (2020) | Climate communication in Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe |

| Leal Filho et al. (2024) | AI for climate change adaptation in Africa. | Africa |

| Ngulube (2024) | ICTs for sustainable agriculture in Africa. | Africa |

| Nwankwo et al. (2019) | IoT in climate messaging. | Nigeria |

| Chimaya and Kanja (2020) | ICT for climate change adaptation. | Zambia |

| Yohannis et al. (2019) | ICT tools for climate change information access. | Kenya |

| Brummer (2024) | Block chain for agriculture traceability in South Africa. | South Africa |

| Mukavaro et al. (2023) | Climate communication in rural Zimbabwe. | Zimbabwe |

| Chapungu, Nhamo, and Matsa (2024) | Climate related challenges in agriculture | Southern Africa |

| Naidoo (2024) | Challenges in accessing climate information. | South Africa |

| Sansa-Otim et al. (2022) | Weather information dissemination. | Uganda |

| Khatibu and Ngowi (2025) | Climate information services | SSA |

| Carr, et al. (2020) | Climate information services | SSA |

| Shimhanda and Vivian (2022) | Media coverage of climate change | Namibia and South Africa. |

| Onyancha and Onyango (2020) | ICTs for Agriculture (ict4ag) | SSA |

| Amarnath (2020) | Smart ICT for climate communication | Sudan |

| Chavula, Kayusi, and Juma (2024) | AI challenges in climate communication. | SSA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).