Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods:

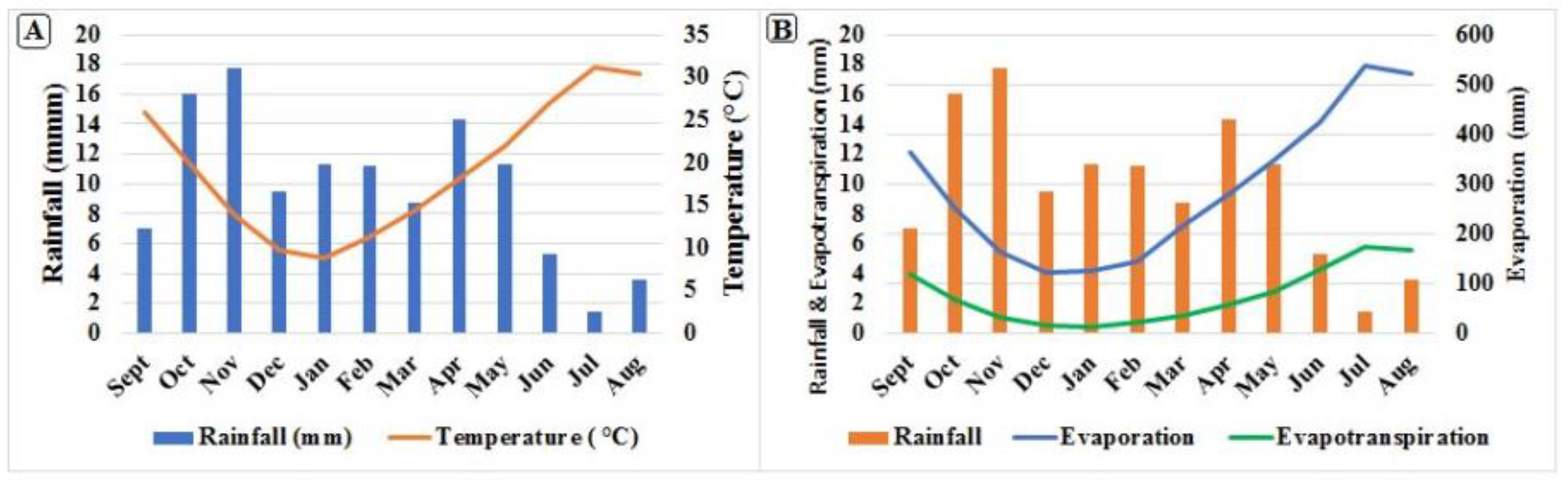

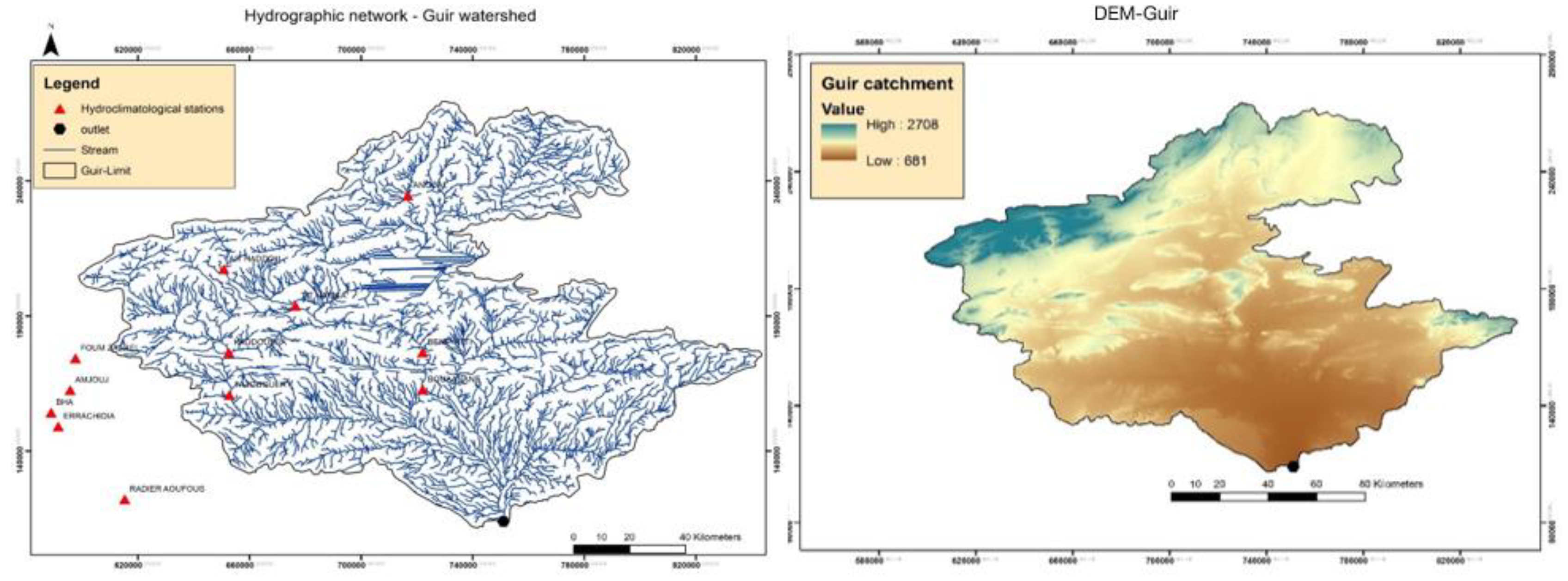

2.1. Study Area: Guir Catchment

2.2. Methodology and Datasets

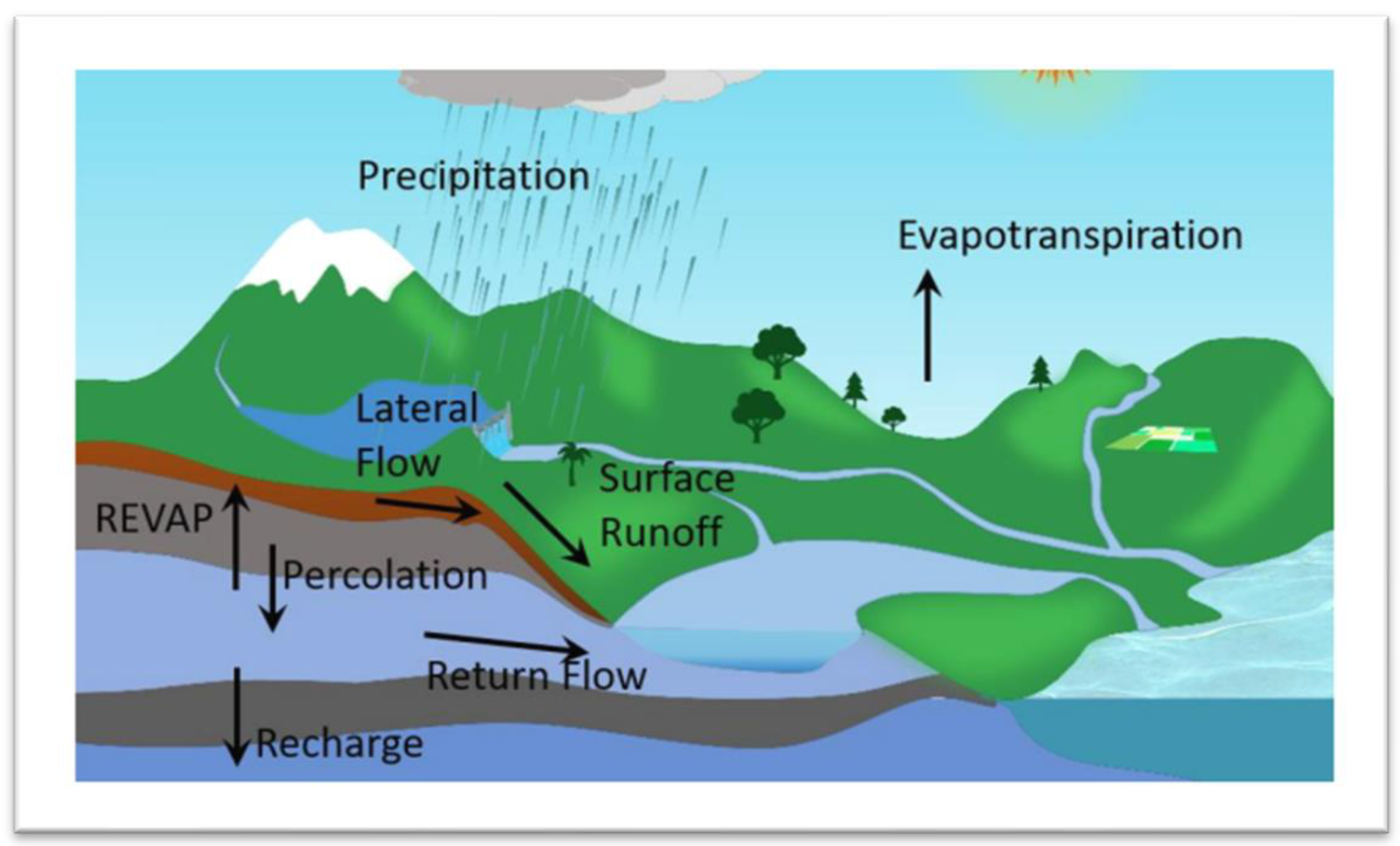

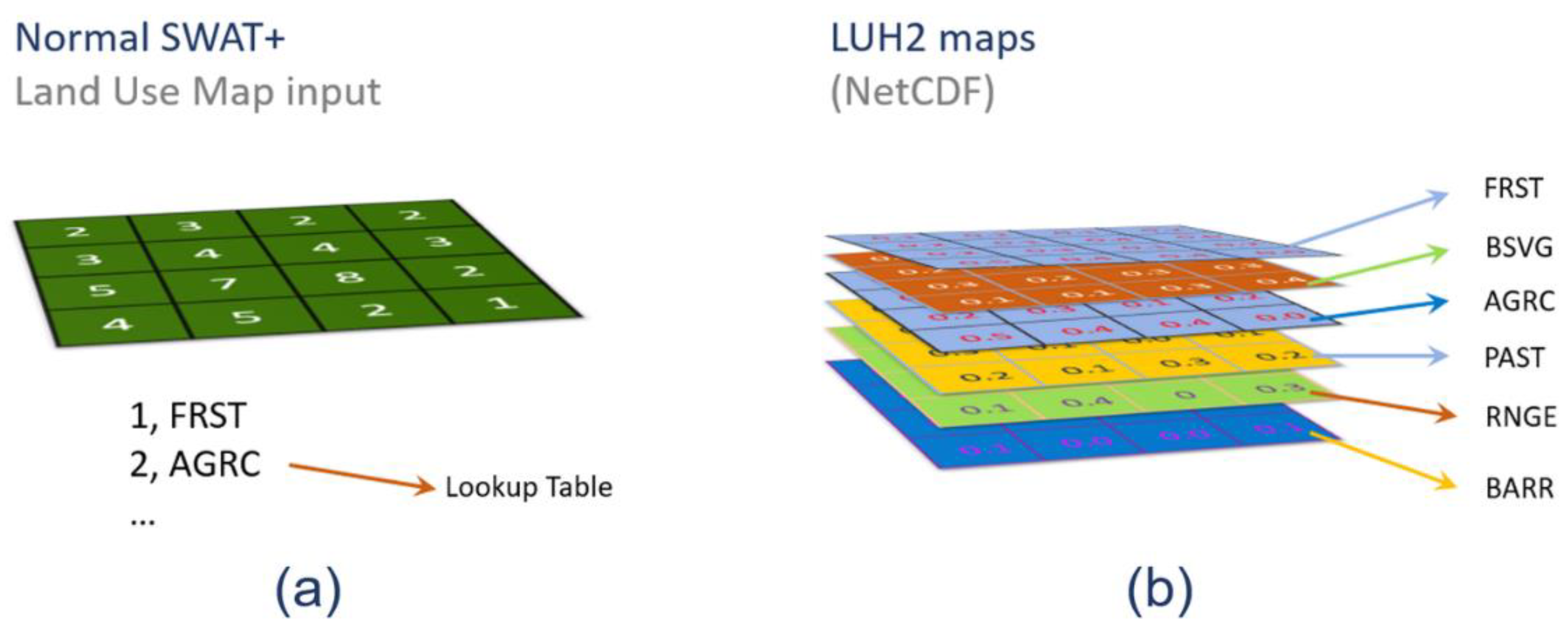

2.2.1. SWAT+ Model Set Up

- it manages large datasets more efficiently due to its SQLite-based structure, and

- it incorporates a plant community module that allows simulation of multiple crop types (e.g., date palms) within the same HRU.

2.2.2. Global Datasets and Inputs Used for SWAT+ Model and Climate Change Scenarios

- (a)

- Digital Elevation Model (DEM):

- (b) Land Use/Land Cover:

- (c) Soil Data:

- (d) Meteorological Data (Historical Period):

- (e) Climate Change Scenarios (Future Period):

2.2.3. Scenarios Setup

3. Results and Discussion

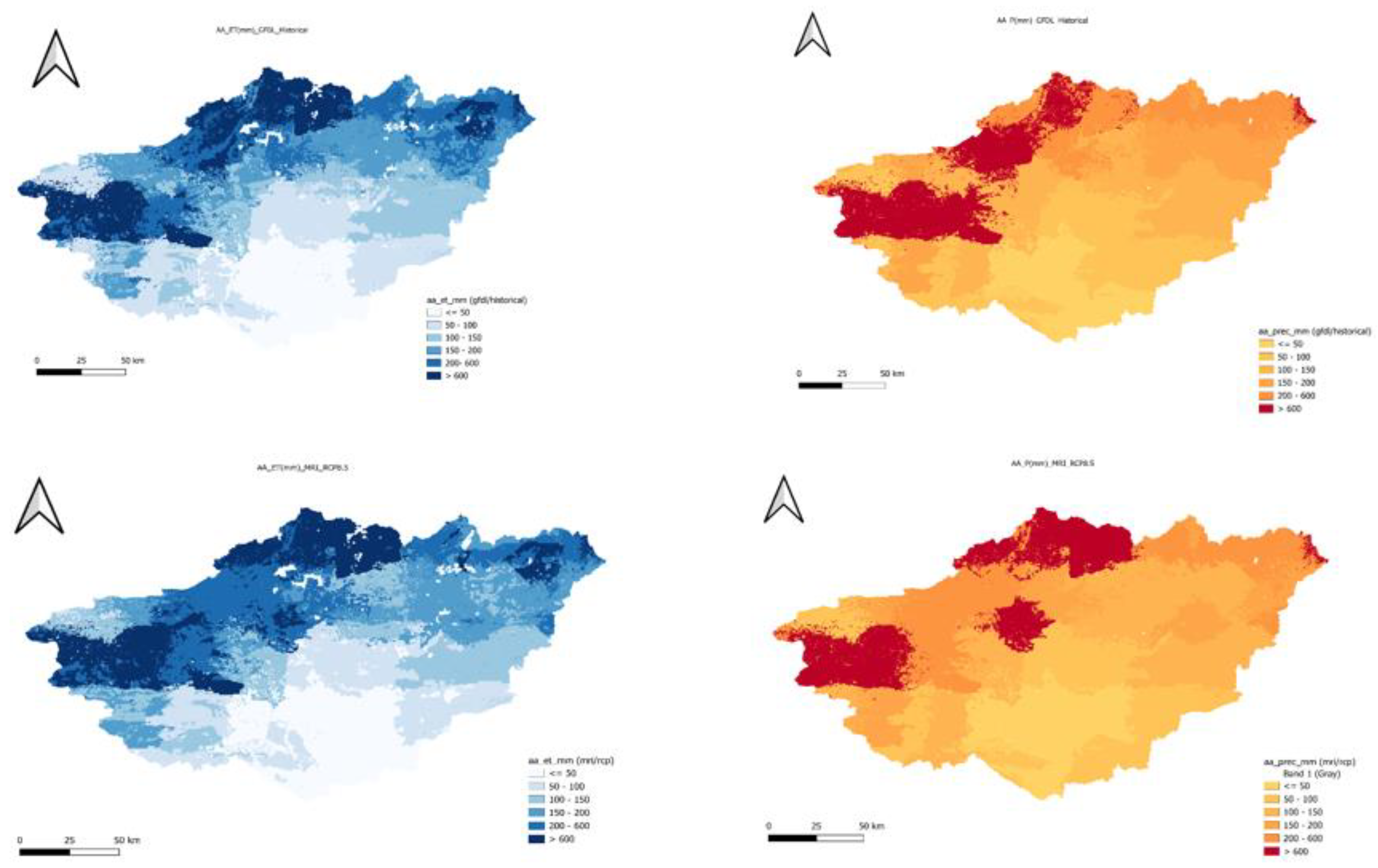

3.1. Simulation of CC Impact on Precipitation P

3.1.1. Historical Yearly P

3.1.2. RCP8.5 Yearly P

3.2. Simulation of CC Impact on Evapotranspiration ETR

3.2.1. Historical Yearly ET

3.2.2. RCP8.5 yearly ET

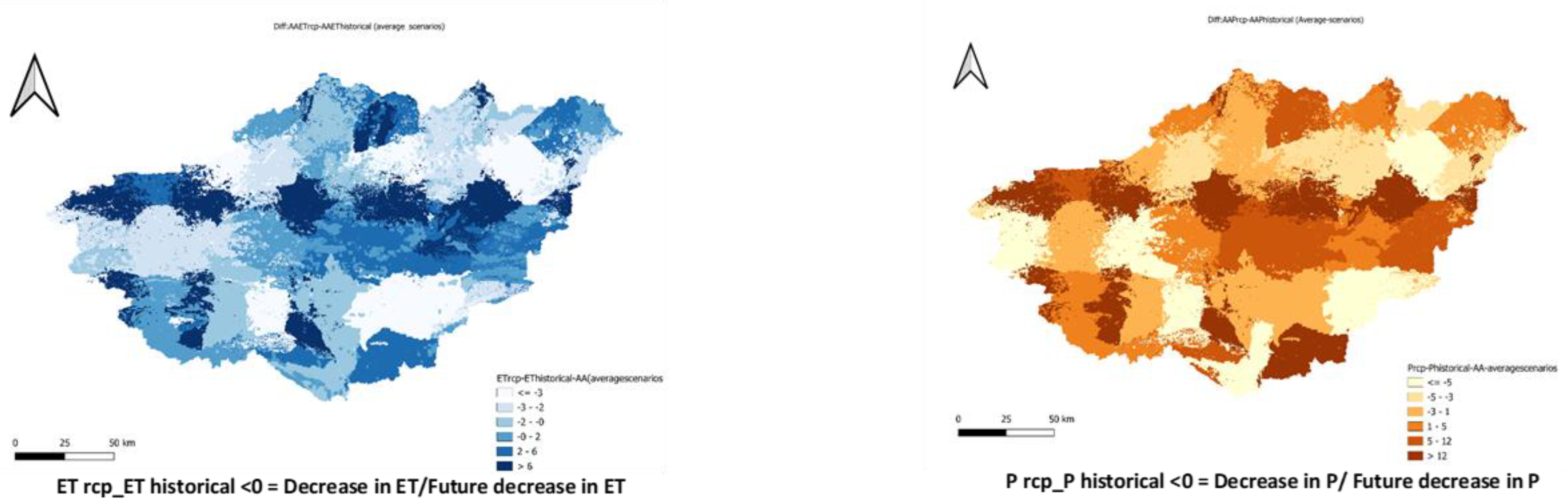

3.3. CC Results Discussions and Comparison

3.3.1. Historical and Future RCP 8.5 Annual Average AA ET vs Historical AA P

3.3.2. Quantitative Summary for CC Scenarios for the Guir Basin

4. Conclusion

References

- Ater, M.; Styring, A.; Younes, H.; Fraser, R.; Neef, R.; Pearson, J.; Bogaard, A. (2016). Disentangling the effect of farming practice from aridity on crop stable isotope values: A present-day model from Morocco and its application to early farming sites in the eastern Mediterranean. The Anthropocene Review, 3(2), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Karmaoui, A.; Balica, S.F.; Messouli, M.; et al. Analysis of the Water Supply-Demand Relationship in the Middle Draa Valley, Morocco, under Climate Change and Socio-Economic Scenarios. *J. Sci. Res. Rep.* **2016**, *10*(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Messouli, M.; Ben Salem, A.; Karmaoui, A. (2009). Ecohydrology and groundwater resources management under global change: A pilot study in the pre-Saharan basins of southern Morocco. Ecohydrology and Groundwater Management, 1, 1–15.

- Benabdelouahab, T.; Gadouali, F.; Boudhar, A.; et al. (2020). Analysis and trends of rainfall amounts and extreme events in the Western Mediterranean region. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 141, 309–320. [CrossRef]

- El-Fadel, M.; Deeb, T.; Alameddine, I.; Zurayk, R.; Chaaban, J. (2018). Impact of groundwater salinity on agricultural productivity with climate change implications. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 13(3), 445-456. [CrossRef]

- Mejjad, N.; Laissaoui, A.; El-Hammoumi, O.; Benmansour, M.; Benbrahim, S.; Bounouira, H.; Benkdad, A.; Bouthir, F.Z.; Fekri, A.; Bounakhla, M. (2016). Sediment geochronology and geochemical behavior of major and rare earth elements in the Oualidia Lagoon in western Morocco. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 309(3), 1133–1143. [CrossRef]

- Milano, M.; Ruelland, D.; Fernandez, S.; Dezetter, A.; Fabre, J.; Servat, E.; Thivet, G. (2013). Current state of Mediterranean water resources and future trends under climatic and anthropogenic changes. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 58(3), 498–518. [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J.; Freier, K.; Hertig, E.; Scheffran, J. (2012). Climate change, vulnerability and adaptation in North Africa with focus on Morocco. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 156, 12–26. [CrossRef]

- Marchane, A.; Tramblay, Y.; Hanich, L.; Ruelland, D. (2017). Climate change impacts on surface water resources in the Rheraya catchment (High Atlas, Morocco). Hydrological Sciences Journal, 62(6), 979–995. [CrossRef]

- Mehdaoui, R.; Mili, E.-M. (2016). Drought Climatic Characterization Watershed of Guir (South East, Morocco) Using Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI). International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 7(6), 1931–1936. [CrossRef]

- Ministère de l’Équipement et de l’Eau. (2009). Rapport sur les Ressources en Eau du Maroc. Direction Générale de l’Hydraulique, Rabat, Maroc.

- Ministère de l’Équipement et de l’Eau. (2009). Rapport sur les Ressources en Eau du Maroc. Direction Générale de l’Hydraulique, Rabat, Maroc.

- Nouayti, A.; Khattach, D.; Hilali, M.; Nouayti, N. (2019). Mapping potential areas for groundwater storage in the High Guir Basin (Morocco): Contribution of remote sensing and GIS. Journal of Groundwater Science and Engineering, 7(4), 309–322. [CrossRef]

- Nouayti, N.; Khattach, D.; Hilali, M. (2017). Potential areas mapping for the groundwater storage in the High Ziz Basin (Morocco): Contribution of remote sensing and geographic information system. Bulletin de l’Institut Scientifique, Rabat, Section Sciences de la Terre, 39, 45–57.

- MILI, R. M. E.-M. (2018). Drought Climatic Characterization Watershed of Guir (South East, Morocco) using Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI). International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 7(6), 1931–1936. [CrossRef]

- ABHZGH, Watershed Agency in Morocco.

- Elbouqdaoui, K.; Ezzine, H.; Zahraoui, M.; Rouchdi, M.; Badraoui, M. (2006). Évaluation du risque potentiel d’érosion dans le bassin-versant de l’oued Srou (Moyen Atlas, Maroc). Science et Changements Planétaires / Sécheresse, 17(3), 425–431. [CrossRef]

- Driouech, F. (2010). Distribution des précipitations hivernales sur le Maroc dans le cadre d’un changement climatique: descente d’échelle et incertitudes. Doctoral Dissertation, Institut National Polytechnique de Toulouse-INPT, Toulouse, France. Toulouse.

- C.J. Chawanda. (2021). PhD Thesis., 1–148.

- Neitsch, S.L.; Arnold, J.G.; Kiniry, J.R.; Williams, J.R. (2011). Soil & Water Assessment Tool: Theoretical Documentation, Version 2009. Texas Water Resources Institute, 1–647. [CrossRef]

- Bieger, K.; Arnold, J.G.; Rathjens, H.; White, M.J.; Bosch, D.D.; Allen, P.M.; Srinivasan, R. (2017). Introduction to SWAT+: A Completely Restructured Version of the Soil and Water Assessment Tool. Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 53(1), 115–130. [CrossRef]

- Pechlivanidis, I.; Jackson, B.; McIntyre, N.; Wheater, H. (2011). Catchment scale hydrological modelling: A review of model types, calibration approaches and uncertainty analysis methods in the context of recent developments.

- Bosznay, Á.P. (1989). On the lower estimation of non-averaging sets. Acta Mathematica Hungarica, 53(1), 155–157. [CrossRef]

- Green, W.H.; Ampt, G.A. (1911). Studies on Soil Physics, Part I – The Flow of Air and Water Through Soils. Journal of Agricultural Science, 4(1), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.; Bieger, K.; White, M.; Srinivasan, R.; Dunbar, J.; Allen, P. (2018). Use of decision tables to simulate management in SWAT+. Water, 10, 713. [CrossRef]

- Chawanda, C.J.; Arnold, J.; Thiery, W.; van Griensven, A. (2020). Mass balance calibration and reservoir representations for large-scale hydrological impact studies using SWAT+. Climatic Change, 163(3), 1307–1327. [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Kempen, B.; Leenaars, J.G.B.; Walsh, M.G.; Shepherd, K.D.; Tondoh, J.E. (2015). Mapping soil properties of Africa at 250 m resolution: Random forests significantly improve current predictions. PLoS ONE, 10(6), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Ayana, E.K.; Dile, Y.T.; Narasimhan, B.; Srinivasan, R. (2019). Dividends in flow prediction improvement using high-resolution soil database. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 21, 159–175. [CrossRef]

- Frieler, K.; Lange, S.; Piontek, F.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Schewe, J.; Warszawski, L.; Yamagata, Y. (2017). Assessing the impacts of 1.5°C global warming — simulation protocol of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP2b). Geoscientific Model Development, 10(12), 4321–4345. [CrossRef]

- USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development) 2016, USAID Climate Change Adaptation Plan: 2016–2020s, USAID, Washington, D.C.

- Ajjur, S.B.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. (2021). Evapotranspiration and water availability response to climate change in the Middle East and North Africa. Climatic Change, 166(3), 28. [CrossRef]

- Gong, S. L.; Zhang, X. Y.; Zhao, T. L.; Zhang, X. B.; Barrie, L. A.; McKendry, I. G.; Zhao, C. S. (2006). A Simulated Climatology of Asian Dust Aerosol and Its Trans-Pacific Transport. Part I: Mean Climate and Validation. Journal of Climate, 19(1), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Irmak, S.; Allen, R.G.; Whitty, E.B. (2006). Daily grass and alfalfa-reference evapotranspiration estimates and alfalfa-to-grass evapotranspiration ratios in Florida. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering, 132(3), 238–249. [CrossRef]

- Benzougagh, B.; Al-Quraishi, A. M. F.; Kader, S.; Mimich, K.; Bammou, Y.; Sadkaoui, D.; Ouchen, I.; El Brahimi, M.; Khedher, K. M.; Hakkou, M. (2024). Impact of Green Generation, Green Morocco, and Climate Change Programs on Water Resources in Morocco. Climate Change and Environmental Degradation in the MENA Region, 136, 223-253. [CrossRef]

- Farr, T.G.; Rosen, P.A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Alsdorf, D. (2007). The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Reviews of Geophysics, 45(2), 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Morocco. (2023). Programme Maroc Vert et Adaptation au Changement Climatique. Ministère de l’Agriculture du Maroc. https://www.agriculture.gov.ma/fr/accueil.

- World Bank; Climate Change Knowledge Portal (CCKP). (2021). Climate Risk Country Profile: Morocco. World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/15725-WB_Morocco%20Country%20Profile-WEB.pdf.

- Editions Géologique Pistes du Maroc. (1971). Ressources en Eau du Maroc, Tome 1. Publications du Service Géologique du Maroc, Rabat.

- https://www.epa.gov/arc-x/climate-adaptation-and-source-waterimpacts#:~:text=Climate%20change%20threatens%20the%20quality,increase%20due%20to%20climate%20change).

- United Nations Water. (2024). Climate Adaptation and Source Water Impacts. UN Water Reports. https://www.unwater.org/.

- Chawanda, C.J.; Nkwasa, A.; Thiery, W.; van Griensven, A. (2024). Combined impacts of climate and land-use change on future water resources in Africa. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 28(1), 117–138. [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P. (2012). The Climate of the Mediterranean Region. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Combe, J., Martin, P., & Bernard, L. (1971). Hydrogeological study of the Guir watershed, southeastern Morocco. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 3(2), 115–128.

| Period | Scenario | GCM forcing |

| 1984-2015 | historical | GFDL |

| IPSL | ||

| MPI | ||

| MRI | ||

| UKESM | ||

| 2070-2100 | RCP 8.5 | GFDL |

| IPSL | ||

| MPI | ||

| MRI | ||

| UKESM |

| Model | Historical Mean P (1985–2015) | Future Mean P (2071–2100, RCP 8.5) | Absolute Change (mm) | % Change | Spatial Trend |

| GFDL-ESM4 | 392 | 276 | −116 | −29.6 % | Strong drying across basin; wet zones restricted to the north |

| IPSL-CM6A-LR | 384 | 272 | −112 | −29.2 % | Pronounced decrease in central and southern zones |

| MPI-ESM1-2-HR | 401 | 295 | −106 | −26.4 % | Gradual drying, persistent wet core in high elevations |

| MRI-ESM2-0 | 389 | 283 | −106 | −27.2 % | Homogeneous decrease, moderate north–south gradient |

| UKESM1-0-LL | 396 | 281 | −115 | −29.0 % | Patchy reduction, isolated wet spots remain in northwest |

| Average | 392.4 | 281.4 | −111 | −28.3 % | Increasing aridity, especially downstream (Boudenib Oasis) |

| Model | Historical Mean ET (1985–2015) | Future Mean ET (2071–2100, RCP 8.5) | Absolute Change (mm) | % Change | Spatial Trend |

| GFDL-ESM4 | 342 | 314 | −28 | −8.2 % | Noticeable decline in central and southern basin; higher ET persists in northern mountainous zones |

| IPSL-CM6A-LR | 338 | 309 | −29 | −8.6 % | Slight reduction across watershed; pronounced in lowland desert areas |

| MPI-ESM1-2-HR | 347 | 318 | −29 | −8.4 % | Moderate decline; ET remains stable near Atlas foothills |

| MRI-ESM2-0 | 350 | 322 | −28 | −8.0 % | Uniform ET decrease, strongest in eastern and arid sectors |

| UKESM1-0-LL | 344 | 315 | −29 | −8.4 % | Reduction concentrated in southern arid zones; persistent wet conditions in highlands |

| Average | 344.2 | 315.6 | −28.6 | −8.3 % | Basin-wide reduction in ET, mirroring decline in precipitation and soil moisture |

| Model | Historical Mean P (1985–2015) (mm yr⁻¹) | Future Mean P (2071–2100) (mm yr⁻¹) | ΔP (mm) | % Change in P | Historical Mean ET (1985–2015) (mm yr⁻¹) | Future Mean ET (2071–2100) (mm yr⁻¹) | ΔET (mm) | % Change in ET | Hydrological Trend Summary |

| GFDL-ESM4 | 392 | 276 | −116 | −29.6 % | 302 | 268 | −34 | −11.3 % | Decrease in rainfall leads to lower ET, drying strongest in south |

| IPSL-CM6A-LR | 384 | 272 | −112 | −29.2 % | 298 | 265 | −33 | −11.1 % | Moderate decline; reduced soil moisture limits ET |

| MPI-ESM1-2-HR | 401 | 295 | −106 | −26.4 % | 310 | 276 | −34 | −11.0 % | Persistent wet zone in north; general ET drop |

| MRI-ESM2-0 | 389 | 283 | −106 | −27.2 % | 304 | 272 | −32 | −10.5 % | Homogeneous drying pattern across basin |

| UKESM1-0-LL | 396 | 281 | −115 | −29.0 % | 307 | 273 | −34 | −11.1 % | Patchy decline: northern ET maintained slightly higher |

| Average | 392.4 | 281.4 | −111 | −28.3 % | 304.2 | 270.8 | −33.4 | −11.0 % | Both P and ET decline; reduced moisture availability dominates |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).