The Rise of Healthspan

Healthspan (or health span) has been defined as the “period of life spent in good health, free from the chronic diseases and disabilities of aging” (Kaeberlein, 2018) or, more simply, the “length of healthy life” (Crimmins, 2015). The term was used as early as the 1960s in the field of geriatric medicine (Masfiah et al., 2025), and while it appeared more often after an influential article published in 1987 (Rowe and Kahn, 1987), only in the 2010s did its appearance in publications soar (Kaeberlein, 2018).

The latter period saw the emergence and spread of a view that the goal of research on aging should be to extend healthspan rather than lifespan. This defined goal was associated with the geroscience agenda, fostered by the US National Institute on Aging (Kennedy et al., 2014; Sierra and Kohanski, 2016), which in turn influenced other aging research initiatives, including the Saudi Hevolution Foundation (Khan et al., 2024).

Extending human healthspan is of course highly desirable. However, within the biogerontology field one increasingly encounters this view that our goal should be to extend healthspan but not lifespan. This view has been stated explicitly, for example by Jay Olshansky, who argued that “life extension should no longer be the primary goal of medicine when applied to people older than 65 years of age. The principal outcome and most important metric of success should be the extension of healthspan” (Olshansky, 2018).

From some perspectives, this is a strange position to take. What is wrong with extending lifespan? We suggest that this anomaly has arisen from conflation of the goals of two distinct disciplines, namely geriatric medicine, that addresses the health needs of older adults, and biogerontology, the study of the biology of aging.

Different Aspirations: Geriatrics vs Biogerontology

Let us consider and contrast the dreams and aspirations of young trainees entering the respective fields of geriatrics and biogerontology. A challenge for geriatricians is that all of their patients will inevitably die from the condition that ails them, namely the process of senescence (aging). Faced with this, laudable and inspiring goals for geriatric medicine were set out by a visionary of the field, James Fries (Fries and Crapo, 1981). Fries’ vision accepts the harsh fact that, as in most animal species, there exists an upper ceiling for human longevity. This reality was confirmed by arrival of rising records of worldwide human maximum lifespan at their upper limit in the 1990s (Dong et al., 2016).

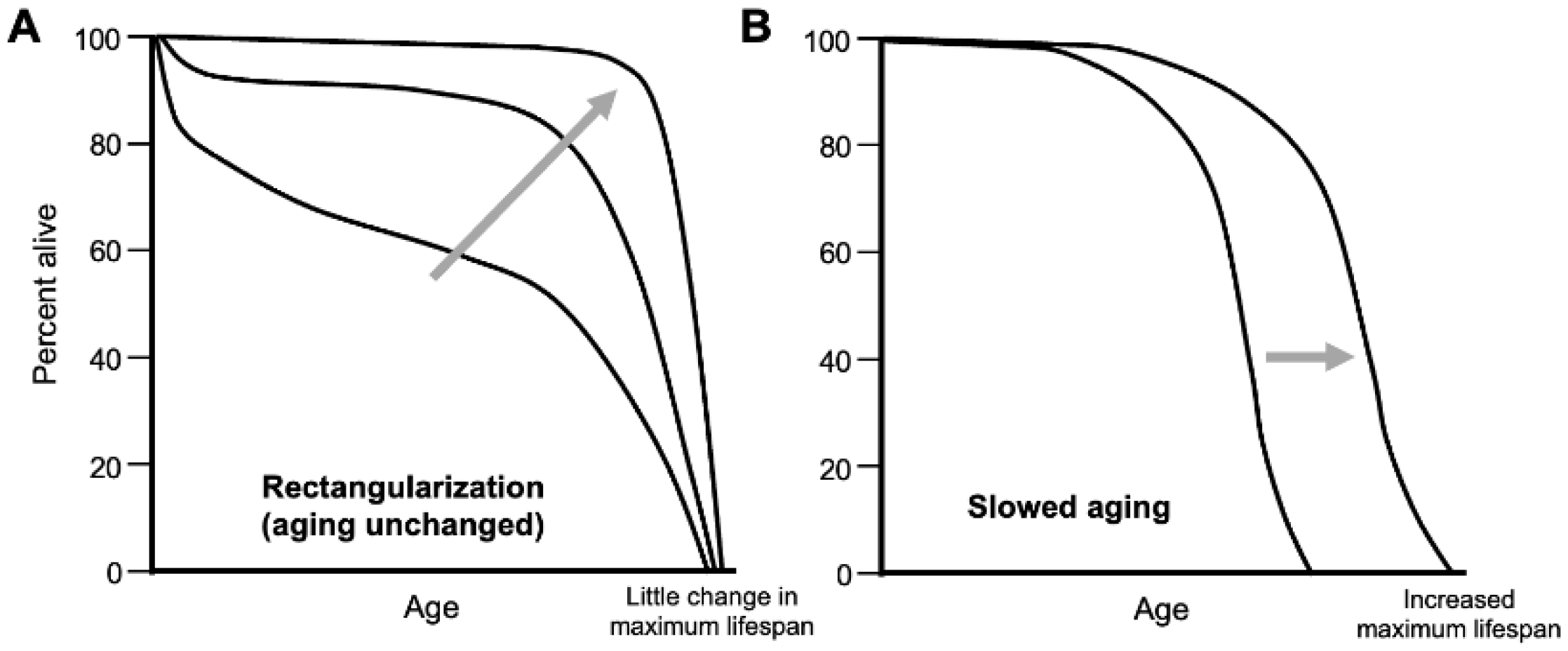

Thanks to improvements in public health during the last century or so, an increasing proportion of the population are living longer lives, coming closer to the longevity ceiling. This is reflected in an increasing rectangularization of population survival curves (

Figure 1A). Fries argues that the goal of late-life medicine should be to reduce the proportion of later life in poor health: “The rectangularization of the survival curve may be followed by rectangularization of the morbidity curve and by compression of morbidity” (Fries, 1980).

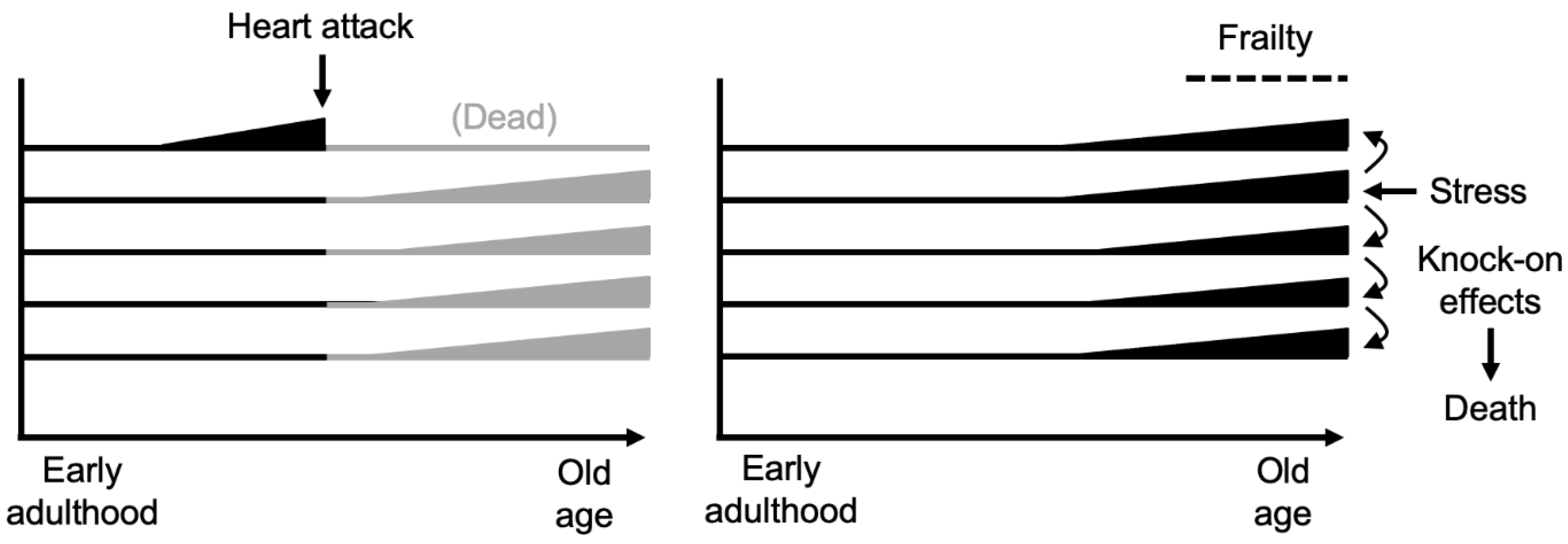

Central to Fries’ vision is the critical role of frailty. Very late in life, this increases to an extent that death comes easily and quickly from even minor insults - a fall, a bacterial infection. Death from advanced frailty offers the best case scenario in terms of compression of morbidity. Drawing on an essay by Lewis Thomas (Thomas, 1980), Fries likens such a good death to the ancient one hoss shay (chaise, two-wheeled carriage) of Oliver Wendell Holmes’ poem (Fries and Crapo, 1981), which

...went to pieces all at once,

All at once, and nothing first,

Just as bubbles do when they burst.

This almost suggests the possibility of death without disease or illness, though of course frailty is a consequence of systemic fragility resulting from weaknesses in many aspects of physiology, reflecting the presence of widespread pathology and functional impairment (

Figure 2).

In the context of Fries’ goals for geriatrics, recommendations of a focus on healthspan rather than lifespan, such as Olshansky’s, quoted above, are well founded. By studying the aging process, means may be found to prevent late-life diseases that cause death prior to late frailty - such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, COPD, Alzheimer’s disease - to grant as many as possible a sudden, one hoss shay-type end.

By contrast, the vision of biogerontology is very different. Central to it is the possibility of decelerating or even reversing the aging process as a whole, or in its greater part. That this is feasible is suggested by the existence of numerous interventions that extend both healthspan and lifespan in animal models, particularly rodents. These include caloric restriction (Masoro, 2005), mutations reducing growth hormone signaling (Bartke, 2019), and a variety of drugs, as demonstrated by the NIA Interventions Testing Program (Nadon et al., 2017). Aging rate and lifespan also show great plasticity with respect to evolutionary change, with mammalian lifespans ranging from several years in short-lived rodents to several hundred years in bowhead whales (George et al., 1999).

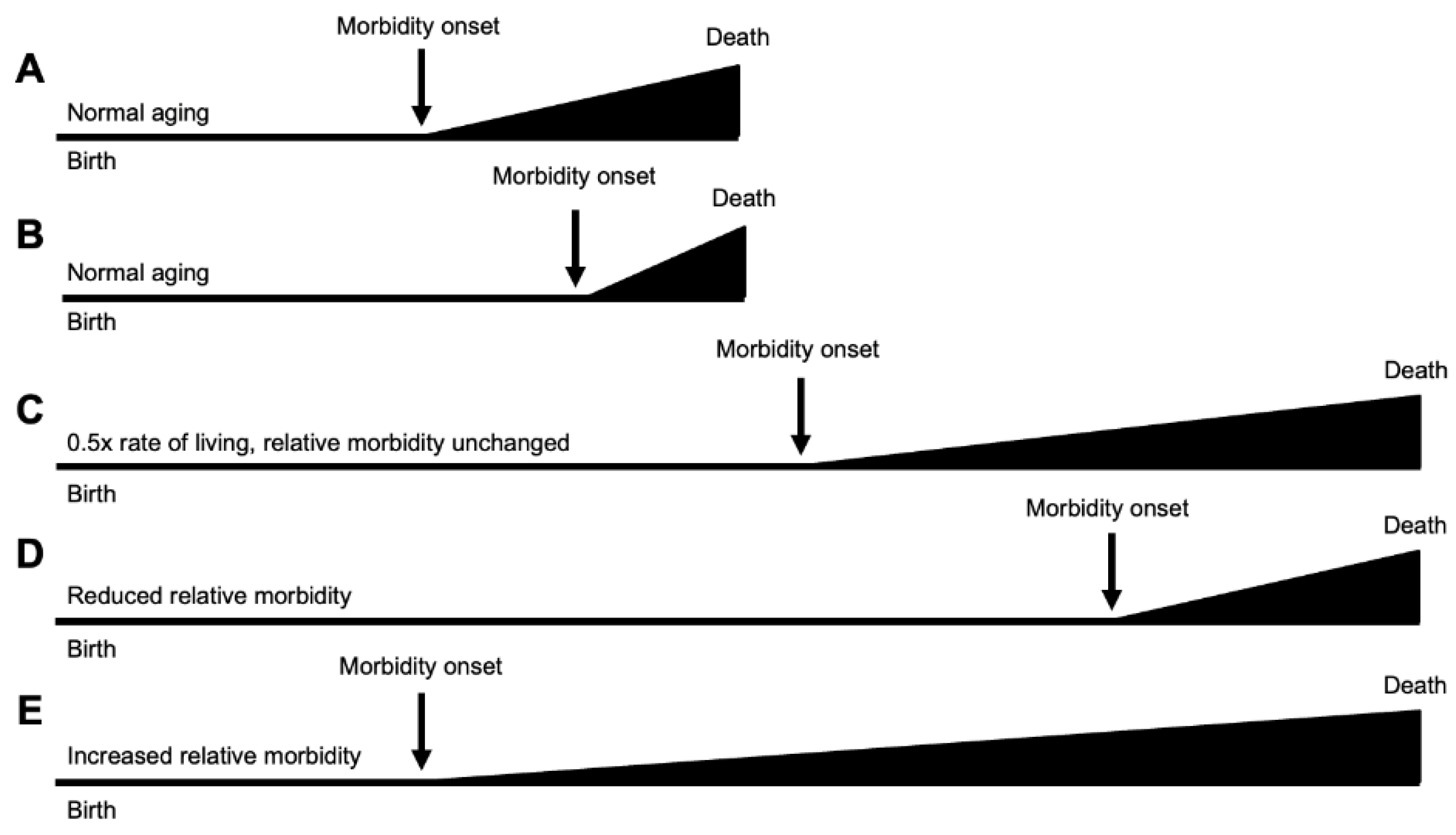

Regarding morbidity, interventions slowing the human aging process could in principle lead to either compression or expansion. Several theoretical possibilities are set out in

Figure 3. A deceleration of the entire adult trajectory, such as that expected from a lowering of temperature in poikilotherms such as nematodes or fruit flies, will result in similar proportional increases in healthspan and gerospan (

Figure 3C). Here the proportion of life in decrepitude is unchanged. Other possible compressions and expansions of healthspan in relative terms are also shown (

Figure 3D,E).

Realistically, there is currently little sign that interventions for humans with major life-extending effects, such as those seen in rodents, will appear any time soon. More plausibly, knowledge derived from the study of the biology of aging will provide insights into the etiologies of late-life disease. This offers great potential in terms of possible new treatments to prevent or postpone late-life disease, and fulfil the geroscience agenda, including compression of morbidity. Our concerns here relate to the more ambitious goals of biogerontology, that lately have grown unfashionable.

Problems with “Healthspan Not Lifespan”

In terms of medical applications, the main, ultimate goal of biogerontologists is much the same as that of most of medical research: to alleviate illness, reduce disease burden, and save lives. In some cases treatments that do this restore patients to full health, and in others they do not. The latter includes many forms of surgical interventions to treat life-threatening conditions, for example where treatment of ruptured bowel, threatening fatal peritonitis, requires creation of a stoma, and use of a colostomy bag.

In the U.S. from the late 1960s until around 2000 there was a steady, marked decline in death rates after 60, particularly from cardiovascular disease. The latter is likely to have increased frequency of death from competing risk diseases such cancer and Alzheimer’s disease. In other words, successful prevention or treatment of cardiovascular disease will have, for some individuals, replaced an earlier, relative quick death (e.g. from myocardial infarction) with a later, slower death that is harder both for the sufferer and their families and carers. In such cases it will have increased the proportion of life spent in poor health.

Clearly there is no ethical reality in which a medical practitioner would argue that it is better to deny people treatments that reduce cardiovascular disease in order to avoid a longer period of ill health at the end of life. A doctor’s duty is to treat illness and save lives, even though it may lead to a longer-life in poor health (palliative care decisions aside). Needless to say, for most people continued life in diminished health (but without severe illness) is preferable to death.

Importantly, the same is true for biogerontologists. Anti-aging treatments will always reduce disease, and may extend lifespan, but whether they increase healthspan and compress morbidity is to a large extent a matter of chance. For a biogerontologist to say that their goal is to increase healthspan but not lifespan is as strange as for a practitioner of any other medical specialism (say, oncology) to say it. Of course, treatments that compress rather than expand morbidity are desirable. But to specify that this is the goal of our research is an impotent claim, and one that may be read as either unrealistic or bogus.

Possibly biogerontologists worry that expressing the view that life extension is a goal of their work risks their being tarred with the same brush as the snake-oil salesmen and mountebanks who make false and exaggerated claims about curing aging (Gieryn, 1983). Alternatively, they may worry about accusations of contributing to over-population, and the increased burden of the aging population on healthcare systems. But of course extending lifespan is a good thing. All medical specialisms hope to increase the number of years spent in good or at least tolerable health, and increases in lifespan are a part of this. Moreover, the aging population is partly a byproduct of the success of healthcare and medical practitioners whose efforts to extend life, unlike those of biogerontologists, are not viewed as insidious (Gems, 2015).

In the U.K. for example, decisions about whether a new medical intervention should be made freely available by the National Health Service are made by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Their judgements are based on the quality-adjusted life years (QALY) added by the treatment. This provides a means of using the limited funds available as efficiently as possible to improve human well being. Increasing QALY is what we hope that anti-aging treatments will achieve and, again, this includes extending lifespan. The aim of preventing death is not peculiar to biogerontology.

Regarding quality of life: arguably what is more important than late-life health or the lack of it is how each individual feels about their life, particularly whether it is worth living. Many people, including some of advanced age, live enjoyable and meaningful lives despite disability and poor health. Arguably, the critical question here is whether an individual prefers life, in whatever condition they are in, to death. What should not greatly influence decisions here, about research goals, is concern about burden on healthcare systems. What is most important here is the humanistic not the economic dimension.

It is right to be very concerned about the crisis facing healthcare systems due to the aging of populations, what has been described as the silver tsunami, and “healthcare asteroid hurtling towards Earth” (Olshansky et al., 2009; Petsko, 2008; Seals et al., 2016). Finding ways to improve healthspan, particularly through public health programs that help keep people in good health into late life (e.g. good nutrition, avoiding obesity, anti-smoking), and promoting compression of morbidity is crucial. But a danger is that, lurking in this agenda, is the old, anti-humanistic philosophy of apologism (Gruman, 1966), that argues that it is beneficial for people to age and die.

Conclusions

We have described how the arguments for healthspan rather than lifespan originated in the field of geriatrics, in which they are cogent, but were subsequently imported into biogerontology, where they are not. Possibly this partly reflects efforts by biogerontologists to align themselves with the agenda of the broader and better funded biomedical field, particularly as part of the geroscience agenda. In the end, medical interventions that save lives and postpone death may or may not cause an expansion of morbidity. Whether they do or not, such interventions are beneficial to the patient, and a good thing. The prospect of a doctor denying a patient a life-saving treatment on grounds that they will remain alive for an extended period in poor health is not part of any ethical reality. We advocate that biogerontologists frankly state their goals of understanding and intervening in aging, to make any gains possible in terms of improvements to late-life health and saving of lives (i.e. life extension).

Acknowledgements

We thank Simon Okholm and Bruce Zhang for helpful discussion and/or comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from LongeCity and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/R014949/1) to J.P.M., and a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (215574/Z/19/Z) to D.G.

References

- Bartke, A. Growth Hormone and Aging: Updated Review. World J. Men's Heal. 2019, 37, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crimmins, E.M. Lifespan and Healthspan: Past, Present, and Promise. Gerontol. 2015, 55, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Milholland, B.; Vijg, J. Evidence for a limit to human lifespan. Nature 2016, 538, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, J.F. Aging, Natural Death, and the Compression of Morbidity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1980, 303, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, J.F. and Crapo, L.M., 1981. Vitality and Aging, W.H. Freeman and Company, San Francisco.

- Gems, D. The aging-disease false dichotomy: understanding senescence as pathology. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.C.; Bada, J.; Zeh, J.; Scott, L.; Brown, S.E.; O'Hara, T.; Suydam, R. Age and growth estimates of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) via aspartic acid racemization. Can. J. Zoöl. 1999, 77, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieryn, T.F. Boundary-Work and the Demarcation of Science from Non-Science: Strains and Interests in Professional Ideologies of Scientists. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruman, G.J. A History of Ideas about the Prolongation of Life: The Evolution of Prolongevity Hypotheses to 1800. Trans. Am. Philos. Soc. 1966, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, M. How healthy is the healthspan concept? GeroScience 2018, 40, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, B.K.; Berger, S.L.; Brunet, A.; Campisi, J.; Cuervo, A.M.; Epel, E.S.; Franceschi, C.; Lithgow, G.J.; Morimoto, R.I.; Pessin, J.E.; et al. Geroscience: Linking Aging to Chronic Disease. Cell 2014, 159, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Al Saud, H.; Sierra, F.; Perez, V.; Greene, W.; Al Asiry, S.; Pathai, S.; Torres, M. Global Healthspan Summit 2023: closing the gap between healthspan and lifespan. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masfiah, S.; Kurnialandi, A.; Meij, J.J.; Maier, A.B. Definitions of healthspan: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 111, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoro, E.J. Overview of caloric restriction and ageing. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005, 126, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadon, N.L.; Strong, R.; Miller, R.A.; Harrison, D.E. NIA Interventions Testing Program: Investigating Putative Aging Intervention Agents in a Genetically Heterogeneous Mouse Model. EBioMedicine 2017, 21, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olshansky, S.J. , 2018. From lifespan to healthspan. JAMA. 320, 1323-1324.

- Olshansky, S.J.; Goldman, D.P.; Zheng, Y.; Rowe, J.W. Aging in America in the Twenty-first Century: Demographic Forecasts from the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on an Aging Society. Milbank Q. 2009, 87, 842–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petsko, G.A. , 2008. A seat at the table. Genome Biol. 9, 113.

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Human aging: usual and successful. Science 1987, 237, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seals, D.R.; Justice, J.N.; LaRocca, T.J. Physiological geroscience: targeting function to increase healthspan and achieve optimal longevity. J. Physiol. 2015, 594, 2001–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burch, J.B.; Augustine, A.D.; Frieden, L.A.; Hadley, E.; Howcroft, T.K.; Johnson, R.; Khalsa, P.S.; Kohanski, R.A.; Li, X.L.; Macchiarini, F.; et al. Advances in Geroscience: Impact on Healthspan and Chronic Disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2014, 69 (Suppl. 1), S1–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, L. , 1980. The Deacon’s Masterpiece. In: The Medusa and the Snail. More Notes of a Biology Watcher. Allen Lane, London, UK.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).