Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignancies among women. It is estimated that 37,682 new cases will be diagnosed in Spain by 2025 [

1]. This increase in incidence is largely attributed to improvements in early detection techniques such as mammography, tomosynthesis, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

2]. The implementation of systematic screening programs and the use of neoadjuvant therapy have contributed to the identification of non-palpable lesions, which has improved overall prognosis and expanded the indications for breast-conserving surgery [

3,

4].

Preoperative localization of these non-palpable lesions is essential to ensure accurate resection and tumor-free margins. Therefore, it is crucial to employ marking techniques that are safe, effective, and do not interfere with imaging or surgical planning [

5,

6].

Traditionally, metallic wires have been used for localization, although they present significant limitations: they must be placed on the same day as surgery, they may shift, and they often cause discomfort for the patient [

7,

8]. These drawbacks can compromise surgical accuracy, increase the risk of positive margins, and lead to the removal of larger amounts of breast tissue [

9,

10]. Nevertheless, their low cost remains a relevant advantage.

Another widely used method is radioguided occult lesion localization (ROLL), which involves the injection of a radioactive tracer followed by intraoperative detection with a gamma probe. Although effective for locating non-palpable lesions [

11], ROLL has several limitations, such as the need for a nuclear medicine unit, radiation exposure, the short half-life of the radiotracer (6 hours), and challenges in cases involving multiple lesions [

12,

13].

Breast-conserving surgery requires accurate localization of non-palpable lesions to ensure adequate resection and tumor-free margins. Positive margins are defined as the presence of tumor cells at the edge of the excised tissue, which is associated with a higher risk of residual disease and local recurrence [

14]. Margin involvement is defined as tumor on ink for invasive carcinoma, and a minimum surgical margin of 2 mm is established for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) [

15].

In response to the limitations of traditional techniques, new technologies such as the SCOUT® system have emerged. SCOUT® is a non-radioactive radar reflector that can be implanted during the diagnostic biopsy, reducing the need for multiple visits to the radiology department. It allows for more flexible surgical planning, provides high localization accuracy, and is compatible with imaging modalities such as MRI [

16,

17]. Its design eliminates protruding wires, enhances patient comfort, and minimizes the risk of displacement. However, its higher cost and the need for specific training are important considerations.

This study aims to evaluate the rate of negative margins achieved with the SCOUT® radar localization system in non-palpable breast lesions and to assess its clinical performance in terms of lesion detection, reoperation rates, and device-related events. We present our experience from a tertiary university hospital, including both benign and malignant lesions, located in the breast and axilla, between January 2023 and May 2024.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective observational study carried out at the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia. It included all patients who underwent surgery between January 2023 and May 2024 in which the SCOUT® reflector was used for determining the location of non-palpable breast lesions.

Inclusion criteria were: patients scheduled for surgery involving localization of non-palpable breast or axillary lesions using SCOUT® reflector. In the group with malignant pathology, patients diagnosed with breast cancer—both early and advanced stages—were included, some of whom had received neoadjuvant treatment prior to surgery. Patients in whom SCOUT® localization was not performed, or who underwent surgery for reasons unrelated to non-palpable breast lesions, were excluded.

All cases were evaluated by a multidisciplinary breast cancer tumor board, and treatment strategies (neoadjuvant systemic therapy vs. upfront surgery) were defined according to individual case characteristics and current European guidelines. MRI was performed preoperatively in all patients who met one or more of the following criteria: ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with dense breasts (ACR categories C or D), invasive lobular carcinoma, or candidates for neoadjuvant treatment. In patients who underwent neoadjuvant systemic therapy, MRI was systematically repeated after treatment to assess tumor response before surgery.

In cases with axillary lymph node involvement at diagnosis, a SCOUT® reflector was placed in the previously biopsied positive node, followed by targeted axillary dissection.

The following main variables were collected to assess the efficacy of the technique and surgical outcomes:

Lesion location: classified according to whether the marker was placed in the axilla or the breast.

Pathology type: benign or malignant.

Seed deactivation: any case in which the seed failed to function due to deactivation, including associated complications or difficulties.

Margin status: tumor-free and positive margins were recorded to evaluate the impact of SCOUT® on surgical precision.

Reoperations: cases requiring reintervention due to positive margins were documented.

Neoadjuvant therapy: all patients who received treatment prior to surgery were recorded.

MRI performed pre- or post-neoadjuvant therapy: whether MRI was performed after neoadjuvant treatment in patients with a SCOUT® seed already placed.

MRI after SCOUT® placement: if performed, any imaging artefacts were noted.

Statistical Analysis:

A descriptive cohort analysis was carried out to evaluate the characteristics of qualitative and quantitative variables in the study. Qualitative variables (e.g., malignant/benign status, detection, pathology type) were described using absolute frequencies and percentages.

Quantitative variables (e.g., age) were summarized using measures of central tendency and dispersion: mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables, and median and interquartile range (IQR) for those that did not meet this criterion.

The normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 26. Descriptive results were presented in tables and graphs to facilitate interpretation.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia. Data were anonymized, and confidentiality was ensured in accordance with current data protection regulations. No additional procedures were performed, and all patients had previously signed informed consent for surgery.

Results

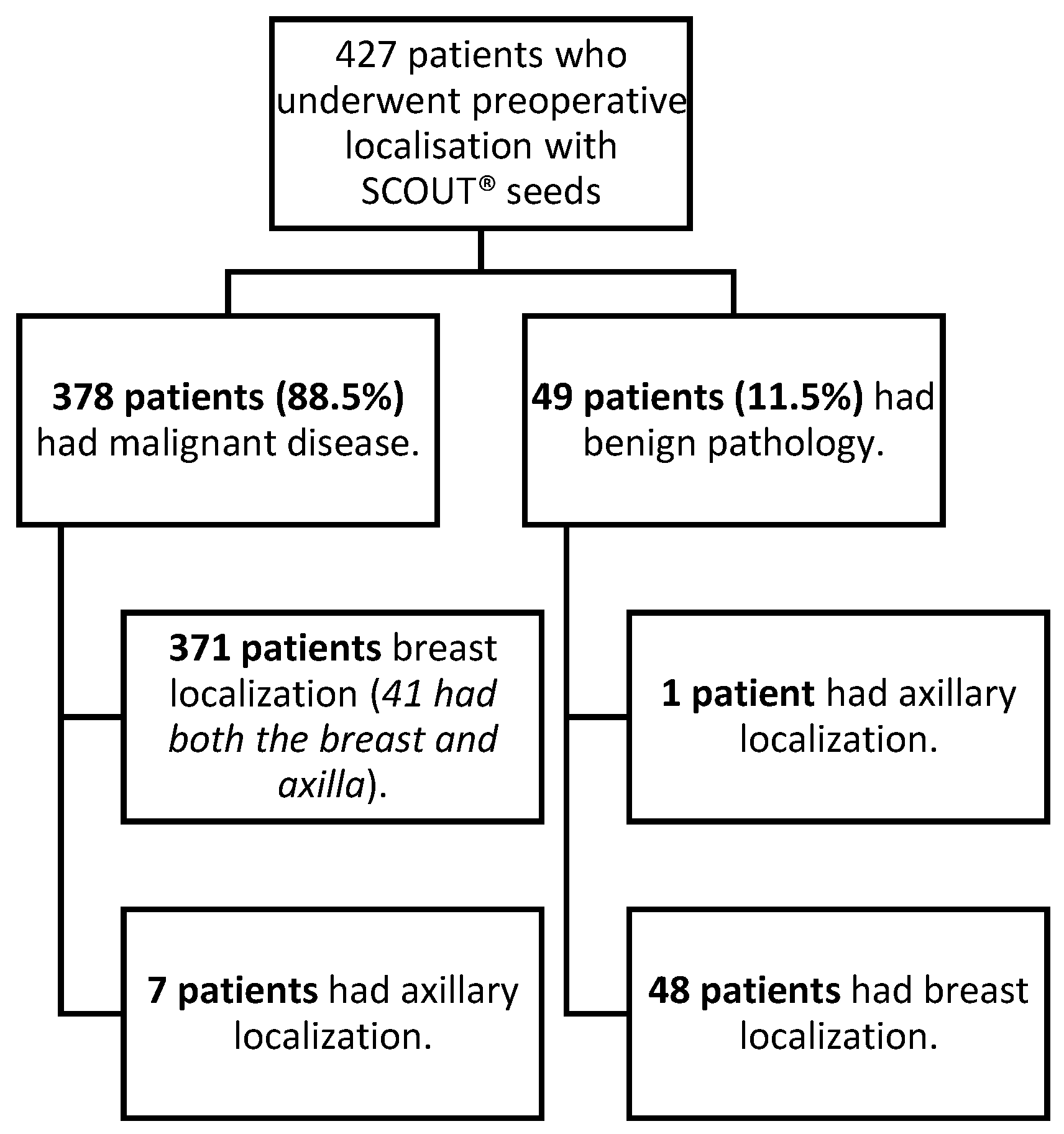

A cohort of 427 patients who underwent surgery between January 2023 and May 2024 was analyzed. All patients had undergone preoperative localization with SCOUT® reflectors for one or more non-palpable lesions located in the breast and/or axilla (

Figure 1). The mean age of the cohort was 58 years (±12.7).

Of the total cohort, 88.5% (n = 378) of patients were diagnosed with malignant disease. The mean age in this subgroup was 59.9 ± 11.6 years. In contrast, the benign subgroup (n = 49) had a significantly lower mean age of 46 ± 13 years (p < 0.001).

Regarding benign lesions localized using the SCOUT® reflector,

Table 1 outlines the variety of benign pathologies identified, with only one case involving axillary localization in the benign pathology group.

In the malignant group, 92.8% of cases corresponded to invasive carcinoma, 6.1% to carcinoma in situ, and 1.1% to other malignancies. These subtypes are detailed in

Table 2, according to molecular profile.

Among patients with malignant disease, 251 (66.4%) underwent MRI at some point during their work-up. Of these, 55 (14.5%) received neoadjuvant systemic treatment prior to surgery. Post-placement MRI was performed in a subset of these patients; only 4 (1.59%) exhibited imaging artifacts attributable to the SCOUT® reflector. These artifacts did not compromise staging or surgical planning.

All patients in whom the axilla had been marked were successfully localized in the operating room. In contrast, 8 breast localizations (1.9%) failed to be detected intraoperatively.

Table 2.

Description of malignant pathology cases.

Table 2.

Description of malignant pathology cases.

| |

n |

% |

| Luminal A |

153 |

40,5 |

| Luminal B |

117 |

31 |

| Luminal B + Her2+ |

16 |

4,2 |

| Her2+ |

23 |

6,1 |

| Triple - Negative |

41 |

10,8 |

|

Carcinoma in situ |

23 |

6,1 |

| Papillary carcinoma |

1 |

0,3 |

| Sarcoma |

1 |

0,3 |

| Lymphoma |

2 |

0,5 |

| Urothelial metastasis |

1 |

0,3 |

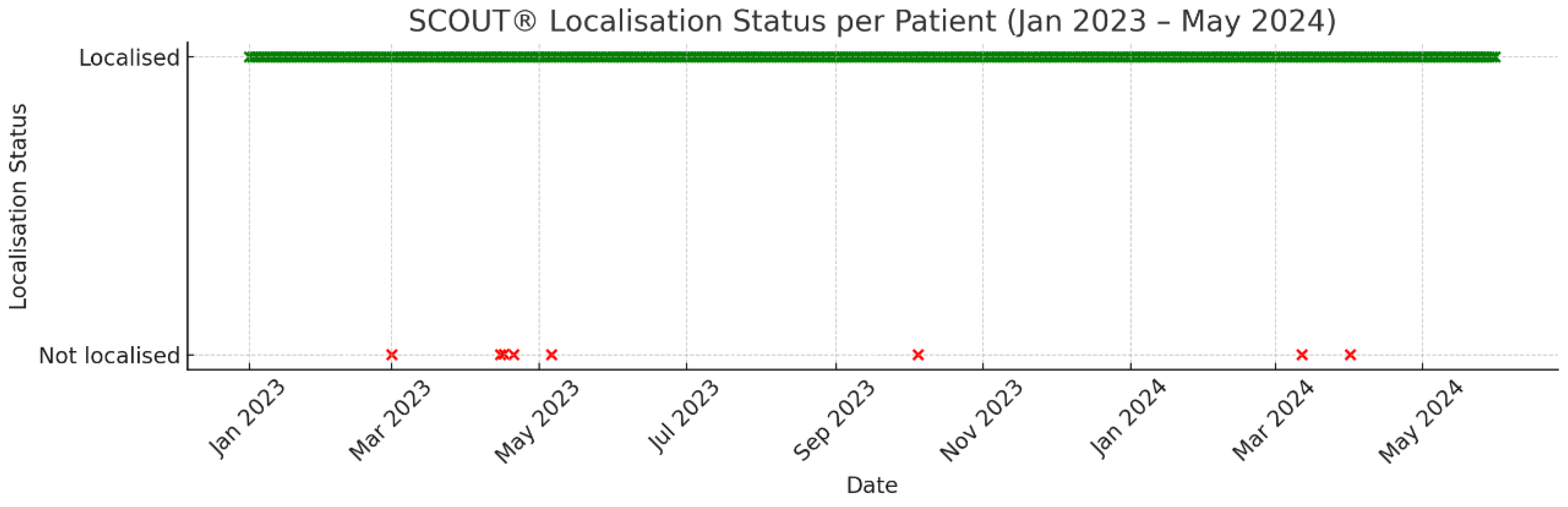

In 5 patients (1.17%), the SCOUT® marker was deactivated. Of these:

In 3 cases, the reflector was localized intraoperatively by manual palpation.

In 2 cases, ultrasound guidance was required for localization.

In one instance, the reflector could not be detected because it had not been placed at the time of the biopsy. Due to pregnancy, the patient did not undergo post-placement mammography, and a wire localization was ultimately performed to guide the lumpectomy. In another case, the reflector was not detected on initial skin assessment and required intraoperative ultrasound-guided wire localization. The SCOUT® reflector was not detected during surgery nor within the excised specimen on the surgical table.

Notably, a higher incidence of deactivation was observed during the early training period of newly incorporated surgeons. However, due to the small number of events, no formal comparative analysis was conducted. These cases are summarized graphically in

Figure 2.

Regarding margin status, 31 patients (8.3%) with malignant pathology presented with positive margins. This rate is lower than our previously reported institutional figure of 12%, suggesting a potential improvement in surgical accuracy since the implementation of the SCOUT® localization system. Among these 31 patients, 22 (5.9%) underwent reoperation, consisting primarily of re-excision or mastectomy depending on the extent and nature of margin involvement.

According to institutional criteria, a positive margin is defined as the presence of tumor on ink for cases of invasive carcinoma, and a margin of less than 2 mm for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

It is important to note that not all patients with positive margins required reintervention. Specifically, those with focally involved ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) at the margin were managed conservatively with adjuvant radiotherapy, in accordance with current clinical guidelines and multidisciplinary team recommendations.

Discussion:

In our study, we evaluated the use of SCOUT® reflectors for the surgical localization of non-palpable breast lesions in 427 patients. Axillary localization was successful in 100% of marked patients, while a non-localization rate of 1.9% (8 patients) was recorded for breast lesions, which is comparable to other series (1.4%) [

19]. There were five cases (1.19%) of radar deactivation, three of which were resolved by direct palpation of the seed, and two by ultrasound guidance.

Comparison with Other Methods

When compared to wire localization, SCOUT® reflector has demonstrated lower rates of positive margins (5.6% vs 13.7%) [

16]. Additionally, wire-localized patients tend to experience higher complication rates, and consequently, require more reinterventions. Although the wire is usually localizable, it may shift or present complications such as wire fracture or haematoma, which may compromise accurate lesion localization and lead to positive margins [

20]. A major limitation of wire localization is the requirement for placement just hours before surgery, entailing close coordination between the surgical and radiology teams [

21]. Nonetheless, its low cost remains a significant advantage.

In comparison, Iodine-125 (I-125) seed localization is associated with a non-localization rate of less than 1% [

22]. Its main advantages include preoperative implantation, which facilitates surgical planning [

23]. However, it presents drawbacks such as radiation exposure [

24] and additional costs associated with the nuclear medicine physician’s and technician’s time. A study by Zhang et al. published in

Annals of Surgical Oncology compared radioactive seed localization (RSL) with wire localization and found that the average cost per patient for RSL was

$250.90, compared to

$1130.41 for wire localisation, including opportunity costs [

25]. In our hospital, each seed costs €100, intraoperative detection approximately €150, with an unknown cost attributed to the nuclear medicine physician who supervises the seed from removal to recovery in pathology. The cost of the wire is €112, while the initial spherical diagnostic marker is €140, requiring two separate radiology sessions.

Magnetic seed technologies such as Magseed offer the advantage of being radiation-free and can be implanted several days prior to surgery [

26]. They are also associated with relatively low rates of positive margins, ranging from 9% to 16.8% [

27,

28]. Their main drawback is cost, averaging approximately

$225 [

29]—in our hospital, €450. Although more expensive than other techniques (€2,617 for wire localization vs €2,662 for magnetic seed localization), cost-effectiveness is achieved when considering reoperation expenses related to positive margins [

30].

Clinical Advantages

Given the variety of localization markers available, it is important to determine the most suitable option for accurate lesion identification while minimizing patient morbidity. However, the ideal marker may vary according to the institution and clinical team. We have implemented the SCOUT® radar system, which enables placement at the time of diagnostic biopsy, avoiding multiple hospital visits for patients. It is suitable for patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy [

16] as it is non-radioactive and can remain indefinitely within the breast. In cases of complete response, the marker remains in situ for subsequent surgical excision or surveillance. It is securely anchored, reducing the likelihood of displacement and positive margins. In our study, 66.4% of patients underwent MRI, with only four (1.59%) demonstrating minor imaging artefacts.

Our series showed a positive margin rate of 8.3%, which is comparable or even favourable compared to other international reports (5.6–9.5%) [

19,

21,

31]. This supports the effectiveness of SCOUT® in the accurate excision of non-palpable lesions.

A notable advantage of the SCOUT® system is its MRI compatibility, owing to the absence of ferromagnetic materials in the reflector, which prevents image distortion [

17,

19]. If the marked lesion is not excised for any reason, the seed can remain safely in place due to its biocompatible materials, which do not provoke adverse tissue reactions [

32]. Furthermore, multiple SCOUT® reflectors may be used in the same breast or patient without interference [

33].

Study Limitations

Nonetheless, SCOUT® is not without limitations. Once deployed by the radiologist, the seed cannot be repositioned, which may be problematic if inaccurately placed [

19]. Detection is limited to depths of 6 cm or less, which may pose challenges in large breasts or in the presence of haematomas [

30,

34]. Deactivation may also occur due to exposure to high temperatures (e.g., from electrocautery) or physical damage such as scissor cuts—although in our experience, functionality may persist even if an antenna is severed. Due to the low number of deactivation cases, we were unable to determine whether a learning curve exists to reduce such occurrences.

Another limitation is the substantial financial investment required. Although SCOUT® is more expensive than wire localization [

36], some studies have shown that its precision and ease of use can reduce operative time, optimize surgical scheduling, decrease reoperation rates, and improve patient comfort—potentially offsetting initial costs [

37,

38]. However, implementation must be adapted to each hospital’s financial and procedural capacity [

39]. In our institution, seeds are placed at the time of diagnosis, eliminating the need for additional visits to the radiology department, thus saving time and cost.

Future Directions

The flexibility of SCOUT® placement at any point prior to surgery enhances scheduling for both patients and clinical teams, reduces operating room delays, improves hospital logistics, and alleviates patient anxiety [

32].

Future research should include prospective, multicenter studies and incorporate assessments of patient quality of life. Additionally, investigation into the surgeon’s learning curve and its effect on deactivation rates would be of value.

Conclusion:

Given the increasing emphasis on breast-conserving surgery and patient-centered care, technologies such as SCOUT® offer a promising tool for optimizing surgical management of breast cancer.

Our findings suggest that SCOUT®-guided localization of non-palpable breast lesions is a safe and effective technique, improving resection precision and reducing positive margin rates, thereby minimizing the need for reinterventions.

Although some cases of non-localization and deactivation were observed, these were infrequent and effectively managed with rescue techniques, reinforcing the overall reliability of this method.

Despite higher costs compared to traditional localization devices, the implementation of SCOUT® at our center has led to significant improvements in surgical outcomes. Its advantages in terms of accuracy, operative efficiency, and patient comfort make it a preferred option in the context of conservative breast surgery.

References

- Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer. Cáncer de mama [Internet]. Madrid: AECC; [unknown date] [cited 2025 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.contraelcancer.es/es/todo-sobre-cancer/tipos-cancer/cancer-mama.

- Barr RG, Zhang Z, Cormack JB, Mendelson EB, Berg WA. Probably benign lesions at screening breast US in a population with elevated risk: prevalence and rate of malignancy in the ACRIN 6666 trial. Radiology. 2013;269(3):701–712. [CrossRef]

- Garzotto F, Comoretto RI, Michieletto S, et al. Preoperative non-palpable breast lesion localization, innovative techniques and clinical outcomes in surgical practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast. 2021;58:93–105. [CrossRef]

- Murphy BL, Boughey JC, Keeney MG, et al. Factors associated with positive margins in women undergoing breast conservation surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(4):429–435. [CrossRef]

- Houssami N, Macaskill P, Marinovich ML, Morrow M. Surgical margins and local recurrence in early-stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(3):717–730. [CrossRef]

- Jeffries DO, Dossett LA, Jorns JM. Localization for breast surgery: the next generation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141(10):1324–1329. [CrossRef]

- Cheung BHH, Co M, Lui TTN, Kwong A. Evolution of localization methods for non-palpable breast lesions: a translational medicine review. Transl Breast Cancer Res. 2024;5:12. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Macarrilla S, Català Forteza J, Vallés Noguero V, Salgado Derqui T. Localización prequirúrgica de lesiones no palpables: pasado, presente y futuro. Seram. 2018;2(1). Available from: https://piper.espacio-seram.com/index.php/seram/article/view/7959.

- Cebrecos I, Sánchez-Izquierdo N, Ganau S, et al. Radioactive and non-radioactive seeds for surgical localization of non-palpable breast lesions. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2022;41(2):100–107. [CrossRef]

- Chagpar AB, Garcia-Cantu C, Howard-McNatt MM, et al. Does localization technique matter for non-palpable breast cancers? Am Surg. 2022;88(12):2871–2876. [CrossRef]

- Srour MK, Kim S, Amersi F, et al. Comparison of wire, radioactive seed, and Savi SCOUT® radar for breast surgery. Breast J. 2020;26(3):406–413. [CrossRef]

- Armas F, Intra M, Vega V, et al. Cirugía radioguiada de lesiones no palpables de mama. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2007;26(2):107–120. [CrossRef]

- Lovrics PJ, Cornacchi SD, Vora R, et al. Radioguided surgery for non-palpable breast cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37(5):388–397. [CrossRef]

- Nayyar A, Gallagher KK, McGuire KP. Definition and management of positive margins in breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2018;98(4):761–771. [CrossRef]

- Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, et al. Personalizing the treatment of early breast cancer: St Gallen consensus 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(9):2206–2223. [CrossRef]

- Tingen JS, McKinley BP, Rinkliff JM, et al. Savi SCOUT vs wire localization: margins and reoperation rates. Am Surg. 2020;86(8):1029–1031. [CrossRef]

- Kasem I, Mokbel K. Savi SCOUT® for non-palpable breast lesions: review and pooled analysis. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(7):3633–3643. [CrossRef]

- Adrianzen M, Buch E, Munoz E, et al. SAVI SCOUT® as an alternative to wires in breast cancer. Ann Case Rep. 2023;8:1157. [CrossRef]

- Wazir U, Kasem I, Michell MJ, et al. SAVI SCOUT® system: prospective evaluation. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(10):2409. [CrossRef]

- Gobardhan PD, de Wall LL, van der Laan L, et al. Radioactive iodine-125 seed localization after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(3):668–673. [CrossRef]

- Alcaide Lucena M, García Martínez MÁ, Gallart Aragón T, et al. Tecnología radar en el marcaje de lesiones no palpables. Cir Andal. 2024;35(3):313–317. [CrossRef]

- Mariscal Martínez A, Solà M, de Tudela AP, et al. Radioguided vs wire localization for breast-conserving surgery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(4):1001–1009. [CrossRef]

- Taylor DB, Bourke AG, Westcott EJ, et al. Surgical outcomes: 125I seed vs hookwire. Br J Surg. 2021;108(1):40–48. [CrossRef]

- Langhans L, Tvedskov TF, Klausen TL, et al. Seed vs wire localization in nonpalpable breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2017;266(1):29–35. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Seely J, Cordeiro E, et al. Seed vs wire localization: cost and OR efficiency. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(12):3567–3573. [CrossRef]

- Pantiora E, Jazrawi A, Hersi AF, et al. Magnetic seed vs guidewire localization: RCT. JAMA Surg. 2024;159(3):239–246. [CrossRef]

- Singh P, Scoggins ME, Sahin AA, et al. Magseed localization for excision of breast lesions. Ann Surg Open. 2020;1(2):e008. [CrossRef]

- Zacharioudakis K, Down S, Bholah Z, et al. Magseed for non-palpable breast cancer: multicentre study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(11):2016–2021. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Magseed for locating impalpable breast lesions [Internet]. London: NICE; 2022 [cited 2025 Mar 9]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib236.

- Lindenberg M, van Beek A, Retèl V, et al. Budget impact of magnetic seed localization. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232690. [CrossRef]

- Patel SN, Mango VL, Jadeja P, et al. Reflector-guided vs wire localization outcomes. Clin Imaging. 2018;47:14–17. [CrossRef]

- Tayeh S, Muktar S, Heeney J, et al. European evaluation of SAVI SCOUT®. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(7):3915–3924. [CrossRef]

- Jadeja PH, Mango V, Patel S, et al. Use of multiple SCOUT® reflectors in same breast. Breast J. 2018;24(4):531–534. [CrossRef]

- Mango VFS, Ha R, Gomberawalla A, et al. Feasibility study: SAVI SCOUT® for excision. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;15:69–72.

- Bundred JR, Michael S, Stuart B, et al. Margin status and survival after breast conservation. BMJ. 2022;378:e070346. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen CL, Cui R, Zhou M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of radar vs wire localization. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31(6):3916–3925. [CrossRef]

- Dashevsky BZ, Muneer MS, Hao M, et al. SCOUT® radar localization at biopsy. J Breast Imaging. 2024;6(4):347–354. [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan GR, Ge C, Lee A, et al. Transition to wireless SCOUT® localization. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2023;44(1):12–17. [CrossRef]

- Farha MJ, Simons J, Kfouri J, et al. SAVI SCOUT® for excision of non-palpable lesions. Am Surg. 2023;89(6):2434–2438. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).