Introduction

Reflexology is a therapy that, through the stimulation of reflex areas, promotes relaxation and supports self-regulatory processes, both physical and emotional, in individuals [

3,

10,

16]. Its mechanism of action largely depends on the methodology applied and the theoretical framework that underpins it [

26], which allows it to be classified within the field of complementary therapies [

48], although in other contexts it is considered an alternative therapy [

49].

Complementary and alternative therapies are not part of conventional medical care. When their methods, physiological understanding and biosafety protocols allow them to be integrated with conventional treatments, they are referred to as complementary. Alternative therapies, on the other hand, are used as substitutes for regular medical care [

1].

It is often not specified whether reflexology is used as a complementary or an alternative therapy. This ambiguity generates distrust regarding its integration with medical treatments and may be counterproductive when the scope of the applied method, its therapeutic objective, and the way manual techniques act, are not clearly understood [

10].

This diversity of approaches generates a wide spectrum of definitions of reflexology, placing the therapy in contexts that range from scientific frameworks to empirical practices or even classifications as pseudoscience [

21]. Few definitions support its therapeutic effectiveness from a physiology-based perspective. Moreover, the lack of reliable research and standardized work protocols complicates the understanding of its physiological mechanisms [

24,

25].

In the context of current scientific research, it is suggested that reflexology can yield positive results related to the regulation and improvement of symptoms in various conditions, depending on the underlying mechanisms of action of its application [

43]. Biological plausibility is a key concept to determine the usefulness of the therapy and to develop research capable of evaluating its safety and efficacy [

26].

For reflexology to be integrated into conventional medicine, its application must demonstrate not only effectiveness but also safety and the ability to generate well-being. Descamps et al. (2023) [

41] evaluate the effect of reflexology on the brain through a study with healthy participants using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The results show brain biomarkers indicating functional connectivity and changes in the default mode network, the sensorimotor network, and the pain-related neural network, confirming that this therapy can safely induce well-being.

Understanding the nervous system mechanisms involved in the action of reflexology is essential to establish the foundations for a precise definition. The nervous system operates through a hierarchical organization composed of different interdependent levels of control: local, reflex, and central. These levels interact with each other to coordinate adaptive responses to external stimuli, maintaining homeostasis both in the short and long term. The described hierarchical structure ensures highly efficient regulation, encompassing responses from simple reflexes to neurocognitive processes that involve brain participation [

2].

In this context, reflexology is considered a complementary therapy based on the manual stimulation of areas located in specific regions of the body, such as the feet and hands. The application of manual stimuli to these areas aims to induce physiological responses through nervous system reflex mechanisms to facilitate allostatic responses [

3].

From a neurophysiological perspective, the therapy acts by activating cutaneous receptors located in the skin (local level), which transmit signals to the central nervous system through afferent pathways. These signals can generate automatic and involuntary responses via reflex arcs (reflex level) to modulate the activity of organs or systems functionally connected to the stimulated areas [

10,

16]. At a more complex level, peripheral stimuli can be integrated into higher levels of the central nervous system (central level), involving structures such as the hypothalamus, brainstem, and limbic system [

16]. At this advanced level, more complex responses occur, including emotional regulation, pain modulation, immune system regulation, and stress reduction, all essential processes for promoting physical balance and psychological well-being. This approach aligns with the hierarchical model proposed by Sammons et al. (2024) [

2], who argue that bodily regulation results from the dynamic interaction among local, reflex, and central mechanisms within the nervous system. The model explains how the body responds in a coordinated manner to internal and external stimuli to maintain homeostasis.

Methodology

The present article was developed under a narrative review and theoretical foundation design, aimed at consolidating a definition of reflexology from a neurophysiological perspective, integrating neurosensory principles and clinical orientations. A systematic documentary search was conducted in scientific databases using the following keywords: Reflexology, Complementary Therapies, Neurophysiology, Autonomic Nervous System, and Regulation.

Original articles, reviews, and academic texts published between 2000 and 2024 in English and Spanish were selected, addressing the physiological action of reflexology, its effect on the nervous system, and its classification within complementary therapies.

Studies lacking clinical support or presenting an exclusively commercial or empirical focus were excluded.

The collected information was analyzed critically and comparatively, integrating the findings from neurophysiological, clinical, and regulatory perspectives. Based on this analysis, a conceptual definition was developed that distinguishes reflexology as a complementary therapeutic practice supported by verifiable physiological mechanisms. Likewise, the distinction between complementary and alternative therapy is emphasized as a key aspect for understanding the therapeutic mechanism of reflexology within a clinical context.

For the review and translation of this manuscript, the artificial intelligence tool ChatGPT, model GPT-5, developed by OpenAI, was used, configured to prevent data from being used to train artificial neural networks.

Reflexology According to International Organizations

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines complementary therapies as those used alongside conventional medicine with the aim of contributing to the overall well-being of patients. Within this context, reflexology is classified as a manual technique that stimulates reflex points on the feet or hands, which are linked, through cartographic maps, to the physiological functioning of the body [

4].

The U.S. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) places reflexology within the category of

complementary manipulative and body-based therapies. It emphasizes that this practice serves as a supportive approach to conventional treatment and can significantly contribute to pain reduction and improvement of quality of life [

5].

Clinical Approach

The clinical concept of reflexology proposes that intervention through stimuli applied to specific areas of the body activates neural reflexes capable of generating therapeutic effects on both physical and emotional levels [

10,

16]. Among its reported benefits are the induction of relaxation responses [

33], pain management [

29,

30,

36], emotional regulation [

8,

37], improved circulation and detoxification [

39], stimulation of the nervous system [

6], enhancement of sleep hygiene [

7,

8,

27,

30,

31], and support for regulatory processes that promote overall well-being [

38] and improve quality of life in illness situations [

9,

28,

32,

34,

35].

Its effectiveness relies on the activation of neural circuits linked to regulatory processes. Each reflex area, when stimulated, triggers adaptive responses in the body that modulate the function of organic structures, promoting improvement in their physiological activity [

10].

Reflexology, grounded in a physiological understanding of the body, clinical assessment, and the application of biosafety protocols, structures sessions in which specific reflex areas are stimulated to activate regulatory processes. In this way, it is configured as a therapeutic accompaniment that fosters balance between body and emotions within a complementary treatment framework [

3,

10].

To define this therapy based on its neurophysiological action, it is essential to understand the relationship between each reflex area and its corresponding physical structure, as well as how a reflex stimulus can regulate the body’s allostatic responses on both physical and emotional levels.

The Action of Reflexotherapies: Reflexology with a Clinical Approach

Reflexotherapies use specific stimuli applied to the surface of the body to elicit reflexes with a defined therapeutic objective [

10,

12,

16].

A reflex is an automatic process of the nervous system designed to facilitate rapid or modulated responses to stimuli, with varying degrees of complexity depending on the number of synapses and higher centers involved [

11].

The metameric or segmental organization of the nervous system is based on the embryological principle of metamerism, which establishes that the human body develops in repeated segments along the cranio-caudal axis, from head to feet. In this process, each segment forms specific connections between the nervous system and the organs or tissues. A metamere includes an area innervated by a nerve from its origin in the spinal cord to its most distal target. Although organs may shift position due to growth or migration, the segmental distribution of innervation remains conserved throughout development. This organization explains the existence of a pre-established functional and structural relationship between certain physical structures and their corresponding reflex areas [

12].

The techniques used in reflexology are applied through manual pressures and movements on specific areas of the feet and hands, known as reflex zones. The stimulus acts upon sensory receptor fibers in the tissues with the objective of activating specific neural pathways [

13,

14,

15].

Reflex zones are grouped into systems that represent the physiological functioning of the organism. These systems are known as microsystems of reflex action. Their locations have been established through both practical experience and scientific evidence, generating a cartography that serves as a guide for the application of reflexology methods.

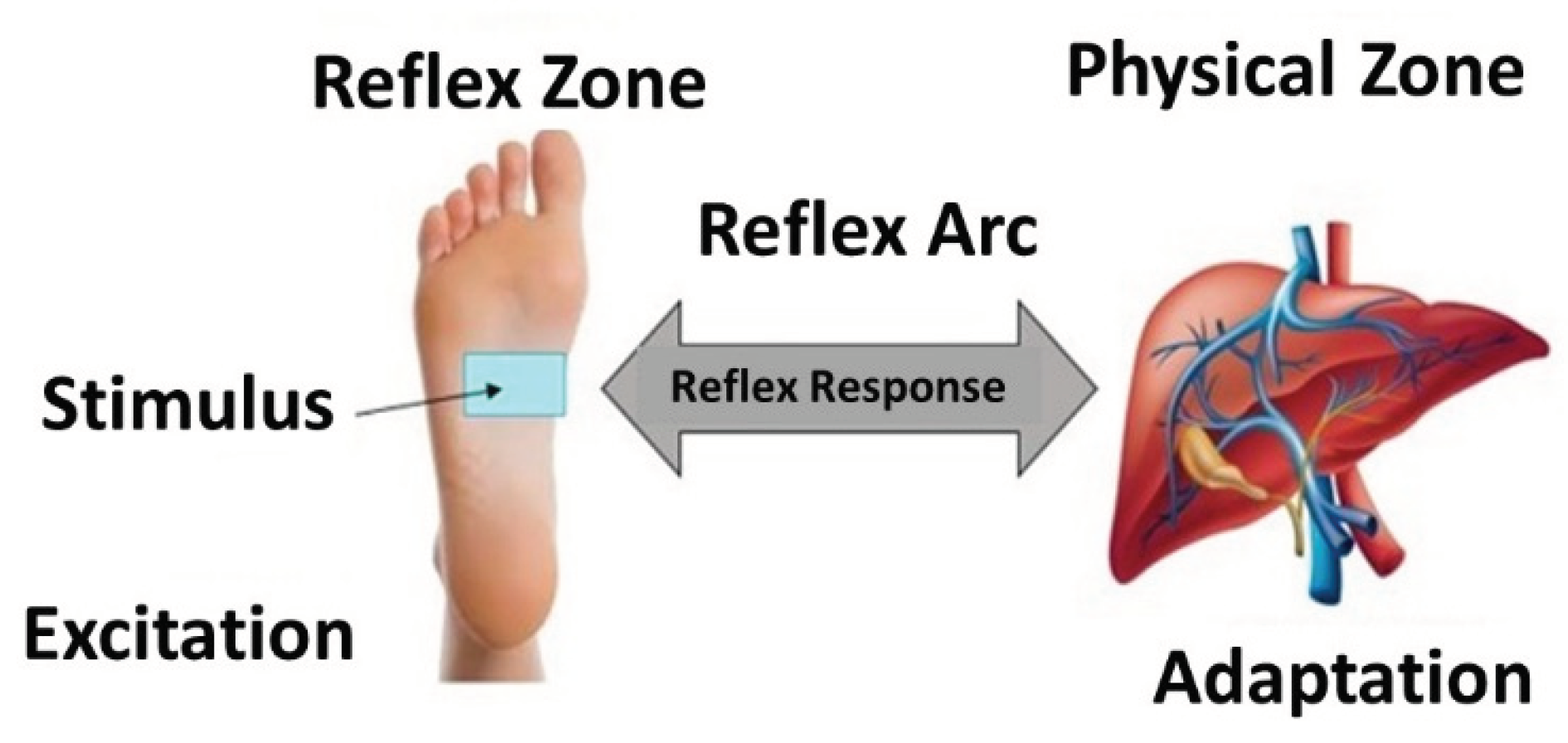

The reflex response produces adaptive effects in one or more somatic structures that correspond to specific areas of the body, these structures are referred to as physical zones. The reflex connection established between a reflex zone and its corresponding physical zone is called a reflex arc [

16]. (

Figure 1)

Somatotopic Correspondence of Reflex Zones

Although the validity of somatotopic mapping remains a subject of debate, there is some evidence supporting its localization, particularly in the context of the plantar (foot) map. The study conducted by Nakamaru et al. (2008) [

17] provides relevant evidence by showing that stimulation of reflex zones on the foot generates specific activation in the corresponding areas of the cerebral cortex. The main objective of that study is to scientifically analyze the somatotopic correspondence between reflex zones and neural centers using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Manual stimulation is applied to three reflex zones on the left foot, related to the eyes, shoulder, and small intestine, while brain activity was recorded via fMRI. The results show that stimulation of each reflex zone produces activation both in the somatosensory area corresponding to the foot and in cortical areas somatotopically associated with the respective organs. Specifically, stimulation of the eye reflex zone activates cortical regions related to vision, while stimulation of the shoulder reflex zone activates the motor cortex associated with that structure. However, the reflex zone corresponding to the small intestine does not show a clearly identifiable cortical activation.

These findings suggest that certain reflex zones of the foot have a somatotopic connection with specific brain regions. The authors propose that the differential cortical representation of visceral organs may explain the observed variability, since visceral organs tend to lack a precise and localized cortical representation that fMRI can easily detect. Moreover, they note that the nature of the manual stimulation method used may have been insufficient to activate a visceral reflex circuit detectable by fMRI. Visceral functions are predominantly related to autonomic and subcortical responses (hypothalamus, brainstem), which are not always represented in the cortex in a way visible through fMRI. This raises the possibility that reflex zones corresponding to visceral organs may not have as precise or direct a somatotopic correspondence with cortical areas, at least not in the same way as somatic structures [

17].

The pilot study by Posse et al. (2024) [

18] provides additional evidence that foot reflexology, applied to healthy participants and to patients with a history of stroke, generates detectable brain responses through real-time fMRI. These results indicate that even when functional limitations exist due to central nervous system injury, reflexology may constitute a neurosensory stimulus capable of activating and modulating brain networks, with potential beneficial effects on motor and sensory functions.

There is also evidence that reflexology produces specific brain activation independent of cognitive suggestion, reinforcing the hypothesis of a physiological basis in the relationship between reflex zones and physical zones. The results show that reflexology consistently activates the primary somatosensory cortex corresponding to the associated body area. This suggests that a direct neurophysiological mechanism is involved rather than cognitive processes of expectation or suggestion [

18,

40].

These studies allow us to establish the existence of a certain level of communication between some reflex zones and their corresponding physical zones, mediated by their reflex arcs within specific neural networks.

Reflex Arc and Polysynaptic Network

Wardavoir H. (2011) [

12], in his article, clarifies the physiological functioning of reflexology, arguing that there is a relationship between the site where a problem originates and its manifestation at a distance. This relationship is established through a reflex arc connecting the physical zone and the corresponding reflex zone.

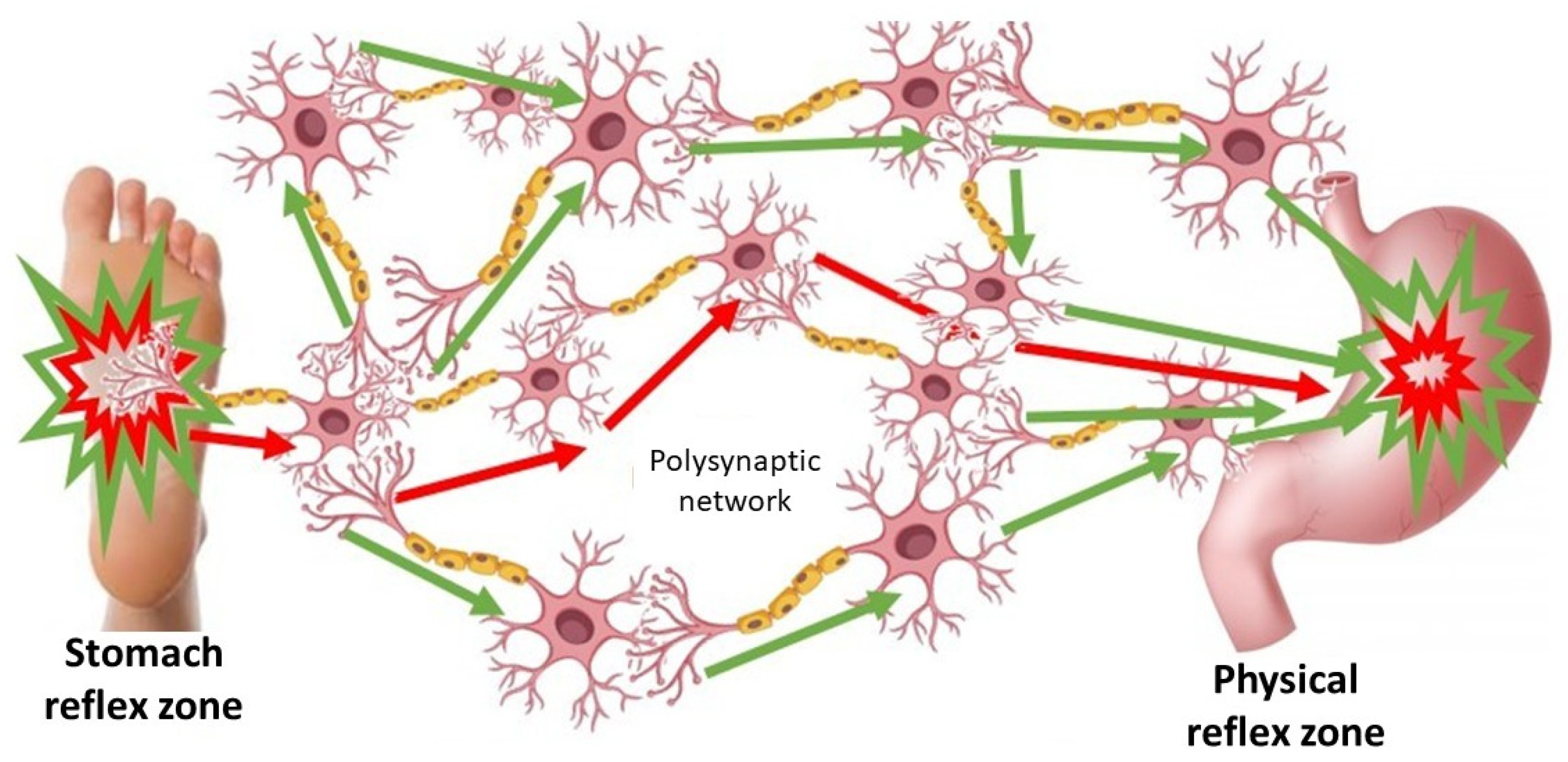

When reflex zones are stimulated, the state of both the physical zones and the reflex zones themselves is modulated. This communication is neither unique nor direct but is influenced by the interactions established among multiple reflex arcs, thus forming a polysynaptic network [

19]. In this complex neural circuit, communication between sensory and motor neurons is mediated by interneurons. More than one synapse is involved to facilitate the integration, modulation, and processing of information before generating a response [

50].

The process of reflex communication and the functioning of the polysynaptic network can be explained by two basic principles:

Within this polysynaptic network, typical neural circuit phenomena are involved, such as the summation of stimuli (addition), facilitation, blocking or reduction of one stimulus by another (facilitation and inhibition), and neuronal convergence, which occurs when different sensory fibers transmit information to the same neurons [

20]. All these processes occur within specific polysynaptic circuits that enable the integration, modulation, and generation of complex reflex signals, activating neural centers that produce responses in different physical zones [

12]. (

Figure 2).

The nervous system has organized circuits in such a way that a peripheral stimulus (in the skin or muscle) can activate a reflex response in distant organs or tissues, thanks to the interconnection of nerves. The response that is triggered is always of the same nature, a phenomenon known as

neuronal specificity [

14,

22].

In Reflexology, stimulation must be applied precisely in order to selectively activate the nerve fibers and reflex pathways responsible for generating a therapeutic effect [

10]. The reflex arcs that are set in motion may be

viscerosomatic or

somatovisceral, depending on the functional direction of the stimulus, specifically, whether it originates in a visceral structure and affects somatic tissues, or begins in a somatic structure and influences a visceral organ. In this context,

visceromusculocutaneous or

cutaneomusculovisceral reflex arcs are described, depending on the starting point and destination of the stimulus and the reflex response that arises [

12].

This configuration represents a

polysynaptic reflex, as one or more interneurons intervene between the sensory (afferent) and motor (efferent) neurons [

22]. Interneurons play a role in integrating, processing, and modulating nerve impulses, allowing the reflex response to exhibit a degree of autonomy and complexity. The neuronal network involved not only transmits information but also regulates and adapts it to the organism’s functional state [

23].

The formed polysynaptic networks allow impulses to converge on common neuronal units, both within the same segment (

intrasegmental) and between different segments (

intersegmental) of the spinal cord. This enables more complex responses that are better adjusted to the body’s needs. It is also important to note that as the number of synapses in the network increases, the speed of the response decreases, but its modulation and adaptability improve. This is especially observed in

suprasegmental reflexes, in which higher centers of the nervous system participate. Although slower than simple reflexes, their responses are more elaborate and better aligned with the organism’s functional demands [

42,

44,

45,

46,

47].

During a reflexology session, different reflex zones related to the problem being treated and to the therapeutic goal are stimulated. These zones interact with one another, forming a complex polysynaptic network aimed at achieving

homeostatic regulation [

10].

It can therefore be established that Reflexology acts through the stimulation of reflex zones with the objective of selectively eliciting physiological responses in corresponding physical areas. These interventions aim to modulate the autonomic nervous system response, improve both local and systemic circulation, and support the body’s self-regulation processes.

Its mechanisms of action are based on:

Metameric reflexes: connections between cutaneous zones and visceral or somatic structures through segmental nerves.

Suprasegmental system: involvement of higher centers such as the reticular formation.

Microsystems of reflex action: applications in localized areas such as the feet and hands, producing both local and systemic effects.

Wardavoir H. (2011) [

12] also points out that the techniques used in reflexology are capable of generating measurable

neurovegetative and vasomotor responses, such as increased blood flow, reduced muscle tension, and modulation of pain perception. These findings provide a

physiological foundation for reflexology practice, moving it away from purely empirical or traditional perspectives. Moreover, they reinforce its interpretation within a

clinical framework, offering a detailed theoretical basis supported by controlled studies and quantifiable data. This legitimizes reflexology as a

complementary therapeutic tool with both academic and clinical support.

Conclusions

Definition of Reflexology with a Clinical Approach Based on Its Neurophysiological Action

Due to the variety of methods and interpretative philosophies surrounding reflexology, it is necessary to establish definitions that clearly delineate its scope in order to use it safely and responsibly, providing conceptual clarity when selecting it as a therapy that can accompany both health and disease processes. Furthermore, a precise definition provides a theoretical framework that enables research development to validate this therapy in the scientific domain.

The definition of Reflexology is grounded in three main criteria:

The relationship between reflex zones and physical structures has been demonstrated through observable brain activation, particularly in the primary somatosensory cortex, and changes in functional connectivity following reflexology application.

The nervous system’s response to stimulation of reflex zones enhances the body’s natural resources for generating allostatic responses.

Clearly defined competencies place reflexology within the complementary field. Evidence indicates that its use is safe, generates well-being responses, and supports processes of illness.

Finally, this article supports the existence of a relationship between a reflex zone and a physical zone, as well as the communication mechanisms of their polysynaptic networks, within criteria that allow integration with medical practice. Based on this, the therapy is defined as follows:

“Reflexology is a complementary therapy that acts through the stimulation of reflex zones located on the feet and hands. Its aim is to induce physiological responses at a distance in linked organs or systems, and its action is based on reflex mechanisms, the involvement of higher centers of the nervous system, and the organization of reflex microsystems operating through polysynaptic networks. This therapy accompanies processes of prevention, health promotion, and functional recovery, supporting self-regulatory mechanisms and adaptive responses of the organism within the framework of an integrative clinical approach.”

Future Perspectives and Limitations

Having a clear and well-founded definition allows clinical reflexology to be framed within healthcare systems. It lays the groundwork for conclusive scientific research and for establishing the competencies and professionalism of practitioners.

Currently, there are limitations related to the lack of well-supported literature and the scarcity of research studies, which often present significant biases and statistically non-significant samples.

Additionally, complementary therapies such as reflexology are not included in the curricula of health and wellness-related programs. This situation creates the risk that training may rely on the subjective perspective of the therapist providing it. Training within healthcare settings is almost nonexistent and largely unrecognized, making inclusion and research in the field difficult.

Moreover, healthcare professionals are often unaware of its scope and methods, making recommendations and integration into care uncommon.

These factors highlight the need to integrate reflexology into healthcare teams, particularly in hospitals and medical centers, based on scientifically grounded scope and evidence.

Finally, by considering its scientific foundations and providing a precise definition of the therapy, this article offers a basis for the development of reflexology within healthcare practice and scientific research.

References

- Briggs, J. P. (2022). Complementary, alternative, and integrative health practices. In Harrison: Principles of Internal Medicine (20.ª ed., cap. 469, pp. 3462-3465). McGraw-Hill.

- Sammons M, Popescu MC, Chi J, Liberles SD, Gogolla N, Rolls A. Brain-body physiology: Local, reflex, and central communication. Cell. 2024 Oct 17;187(21):5877-5890. PMCID: PMC11624509. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, M. A. (2017) Pediatric Reflexology: Approaches to Therapy in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Dunken Publishing.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2002). WHO guidelines on basic training and safety in complementary and alternative medicine. Geneva: WHO. 2014-2023. ISBN 978 92 4 350609 8 https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/95008/9789243506098_spa.pdf.

- NIH. (2021). Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: What’s in a name? National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-orintegrative-

health-whats-in-a-name.

- Lu WA, Chen GY, Kuo CD. Foot reflexology can increase vagal modulation, decrease sympathetic modulation, and lower blood pressure in healthy subjects and patients with coronary artery disease. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011 Jul-Aug;17(4):8-14. [PubMed]

- Marcolin ML, Tarot A, Lombardo V, Pereira B, Lander AV, Guastella V. The effects of foot reflexology on symptoms of discomfort in palliative care: a feasibility study. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023 Feb 28;23(1):66. PMCID: PMC9971681. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasyar N, Rambod M, Najafian Z, Nikoo MH, Yoosefinejad AK, Salmanpour M. The Effect of Foot Reflexology on Fatigue, Sleep Quality, Physiological Indices, and Electrocardiogram Changes in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2024 Sep 4;29(5):608-616. PMCID: PMC11521129. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deenadayalan B, Venugopal V, Poornima R, Kannan VM, Akila A, Yogapriya C, Maheshkumar K. Effect of Foot Reflexology on Patients With Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Int J MS Care. 2024 Mar-Apr;26(2):43-48. Epub 2024 Mar 11. PMCID: PMC10930811. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, M. A. (2024). Reflexology. Techniques I. ISBN 978-631-00-2504-9.

- Dvorkin, M. A. , Cardinali, D. P., & Iermoli, C. (2010). Physiological Bases of Medical Practice (14th ed.). Médica Panamericana.

- Wardavoir, H. (2011). Reflex Manual Therapies. EMC – Kinesitherapy – Physical Medicine, 26-130-A-10.

- Marquardt, H. (2003). Practical Manual of Foot Reflex Zone Therapy. Urano Publishing.

- Sherrington, C. S. (1906). The integrative action of the nervous system. Yale University Press.

- Kunz, K. , & Kunz, B. (2008). Understanding foot reflexology. Reflexology Research Project.

- Manzanares, J. (2003). Principles of Reflexology. Grupo Planeta (GBS).

- Nakamaru T, Miura N, Fukushima A, Kawashima R. Somatotopical relationships between cortical activity and reflex areas in reflexology: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci Lett. 2008 Dec 19;448(1):6-9. Epub 2008 Oct 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posse, S. , Kunz, K., Kunz, B., Van de Winckel, A., Wolf, M., & Yacoub, E. (2024). Neural pathways of applied reflexology using real-time task-based and resting-state fMRI in healthy controls and patients with stroke En 32nd Annual Meeting & Exhibition of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM), Singapur.

- Miura N, Akitsuki Y, Sekiguchi A, Kawashima R. Activity in the primary somatosensory cortex induced by reflexological stimulation is unaffected by pseudo-information: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013 May 27;13:114. PMCID: PMC3668141. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, E. R. , Schwartz, J. H., & Jessell, T. M. (2012). Principles of Neural Science (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Heide, M. , & Heide, M. H. (2009). “Feeling the Teeth through the Feet!”—Plantar Reflexology Massage [Reflexology—Nothing in Common with Scientific Naturopathic Treatments]. Versicherungsmedizin, 61(3), 129–135.

- Guyton, A. C. , & Hall, J. E. (2016). Textbook of Medical Physiology (13.ª ed.). Elsevier.

- Stachowski NJ, Dougherty KJ. Spinal Inhibitory Interneurons: Gatekeepers of Sensorimotor Pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 6;22(5):2667. PMCID: PMC7961554. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritenbaugh C, Verhoef M, Fleishman S, Boon H, Leis A. Whole systems research: a discipline for studying complementary and alternative medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003 Jul-Aug;9(4):32-6. [PubMed]

- Verhoef, M. J. , Lewith, G., Ritenbaugh, C., Boon, H., Fleishman, S., & Leis, A. (2005). Complementary and alternative medicine whole systems research: beyond identification of inadequacies of the RCT. Complementary therapies in medicine, 13(3), 206–212. ISSN 0965-2299. [CrossRef]

- Whatley J, Perkins J, Samuel C. ‘Reflexology: Exploring the mechanism of action’. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2022 Aug;48:101606. Epub 2022 May 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Asltoghiri, Z. Ghodsi, The Effects of Reflexology on Sleep Disorder in Menopausal Women, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Alinia-Najjar R, Bagheri-Nesami M, Shorofi SA, Mousavinasab SN, Saatchi K. The effect of foot reflexology massage on burn-specific pain anxiety and sleep quality and quantity of patients hospitalized in the burn intensive care unit (ICU). Burns. 2020 Dec;46(8):1942-1951. Epub 2020 May 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayari S, Nobahar M, Ghorbani R. Effect of foot reflexology on chest pain and anxiety in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A double blind randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021 Feb;42:101296. Epub 2020 Dec 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakir E, Baglama SS, Gursoy S. The effects of reflexology on pain and sleep deprivation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018 May;31:315-319. Epub 2018 Mar 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmel-Esmel N, Tomás-Esmel E, Tous-Andreu M, Bové-Ribé A, Jiménez-Herrera M. Reflexology and polysomnography: Changes in cerebral wave activity induced by reflexology promote N1 and N2 sleep stages. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2017 Aug;28:54-64. Epub 2017 May 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns C, Blake D, Sinclair A. Can reflexology maintain or improve the well-being of people with Parkinson’s Disease? Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010 May;16(2):96-100. Epub 2009 Nov 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVicar AJ, Greenwood CR, Fewell F, D’Arcy V, Chandrasekharan S, Alldridge LC. Evaluation of anxiety, salivary cortisol and melatonin secretion following reflexology treatment: a pilot study in healthy individuals. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2007 Aug;13(3):137-45. Epub 2007 Jan 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Ellis, et al., A pilot randomised controlled trial investigating the psychological, physiological and biochemical effect of reflexology on breast cancer patients, European Journal of Integrative Medicine 5 (6) (2013) 574–575. [CrossRef]

- Mobini-Bidgoli, M. , Taghadosi, M., Gilasi, H., & Farokhian, A. (2017). The effect of hand reflexology on anxiety in patients undergoing coronary angiography: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 27, 31–36. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, C. A. , & Ebenezer, I. S. (2013). Exploratory study on the efficacy of reflexology for pain threshold and tolerance using an ice-pain experiment and sham TENS control. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 19(2), 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami T, Rejeh N, Heravi-Karimooi M, Tadrisi SD, Vaismoradi M. The Effect of Foot Reflexology on Hospital Anxiety and Depression in Female Older Adults: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork. 2019 Aug 30;12(3):16-21. PMID: 31489059; PMCID: PMC6715326. [PubMed]

- Yaqi, H. , Nan, J., Ying, C., Xiaojun, Z., Lijuan, Z., Yulu, W., Siqi, W., Shixiang, C., & Yue, Z. (2020). Foot reflexology in the management of functional constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 40, 101198. [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y. , Liu, S., Pan, C., Jian, Y., Wang, M., & Ni, B. (2022). The Effects of Foot Reflexology on Vital Signs: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2022, 4182420. [CrossRef]

- Miura, N. , Akitsuki, Y., Sekiguchi, A., & Kawashima, R. (2013). Activity in the primary somatosensory cortex induced by reflexological stimulation is unaffected by pseudo-information: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 13, 114. [CrossRef]

- Descamps, E., Boussac, M., Joineau, K., & Payoux, P. (2023). Changes of cerebral functional connectivity induced by foot reflexology in a RCT. Scientific reports, 13(1), 17139. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska, E. (1992). Interneuronal relay in spinal pathways from proprioceptors. Progress in neurobiology, 38(4), 335–378. [CrossRef]

- Poole, H., Glenn, S., & Murphy, P. (2007).A randomised controlled study of reflexology for the management of chronic low back pain. European Journal of Pain, 11(8), 878–887. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, E. R. , Schwartz, J. H., Jessell, T. M., Siegelbaum, S. A., & Hudspeth, A. J. (2013). Principles of Neural Science (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Purves, D. , Augustine, G. J., Fitzpatrick, D., Hall, W. C., LaMantia, A. S., Mooney, R. D., Platt, M. L., & White, L. E. (2018). Neuroscience (6th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Schomburg E., D. (1990). Spinal sensorimotor systems and their supraspinal control. Neuroscience research, 7(4), 265–340. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M. B. (2011). Core text of neuroanatomy (4th ed.). Williams & Wilkins.

- Mantoudi, A. , Parpa, E., Tsilika, E., Batistaki, C., Nikoloudi, M., Kouloulias, V., Kostopoulou, S., Galanos, A., & Mystakidou, K. (2020). Complementary Therapies for Patients with Cancer: Reflexology and Relaxation in Integrative Palliative Care. A Randomized Controlled Comparative Study. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.), 26(9), 792–798. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E. (2000). The role of complementary and alternative medicine. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 321(7269), 1133–1135. [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, Elżbieta. Spinal Reflexes. En: Neuroscience in the 21st Century (Pfaff, D.W.; Volkow, N.D.; Rubenstein, J.L. eds.). Springer, Cham. 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).